CHAPTER 32

The women then threw off their capes. They cried out that the Spartans had all been killed or scattered in fear of the arrival of Epaminondas. “Our thousands chased down their hundreds. Ask the priestesses of Artemis how many have been hunted down and gutted. The bodies of our masters are scattered all over Ithômê. Talk to Alkidamas. Look, our Alkidamas is here. We have the plans of the city and are ready to have the gods bless the founding—and start tomorrow.”

Bedlam followed as the celebrants lit more torches. The drummers took up the strain. Thousands of Messenians came out of the shadows and mingled in with the Thebans and Argives. Then Alkidamas came forward with a sickly sort of fellow at his side. Ephoros waved as the man addressed the throng. “Patience, silence, my guests. We sleep now. Soon the high priestesses return from Ithômê and Eva with the gods’ nod about our city’s founding. So for now, sleep, our Argive and Theban guests. Lay out your camps and tents. Sleep in peace, we of Messenia have food and peace for you—and a city to build tomorrow.” Then the tribal leaders of the Messenians went into the camp of Epaminondas and waited for his arrival.

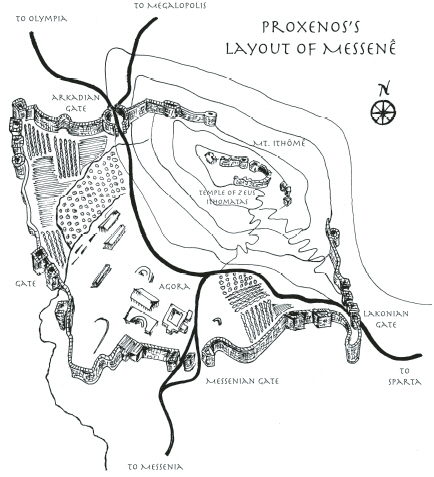

On the next morning Epaminondas called Lelex back to the camp of the generals. Epitêles was at his side, and he was calmer now, since a thousand of his men had found the night quiet and most helots asleep around Ithômê and Eva. Lelex and Doreios, along with Nikôn and some others, sat down as Epaminondas threw down a bag of scrolls taken from the sack of Proxenos. By rote he claimed, “Here. We found them. Just as it was fated that the urn of old Aristomenes would be uncovered when the Spartans left. In it are the plans of the new Messenê, buried on the slopes of Ithômê since the time of the great ones. The priestess Nêto once told us where the goddess had hidden the plans of our city. We have brought the ancient scrolls back from the crypt on Ithômê.”

Lelex went dumb. Before him on the ground of the tent was a pile of Proxenos’s papers, with charts of towers, and four gates, and drawings of the mountain Ithômê and the saddle to Eva surrounded with walls running up the sides of Ithômê—which he believed had been unearthed from a crypt just dug from the ground of the mountain, written, he thought, hundreds of years earlier. “Artemis of Ithômê. We are where we should be. We are standing on the city walls of our grandchildren. So we will start today with the quarrying. Tisis here will organize the companies.” For the rest of their second day in Messenia, the Boiotian generals divvied up the protection of the Messenians with the Argives. One myriad would guard the workers. The other ten thousand would join with the Messenians laying the foundation trenches, some thirty stadia of them. Fifty thousand Messenians were to stay up on Ithômê, cutting and dragging down the gray stone. Another twenty thousand would work the machines to hoist the blocks and guide the iron and lead mongers to fasten the stones. Half the women were to cook, as they hunted down the Spartan stores and the caches in the abandoned Spartan camps. The other half set up tents and shacks for the workers and hoplites. Nikôn’s crews already had cut tall spruce timber, forty feet and more. With the help of Ainias, he was planning to build ten tall swiveling cranes, with pulleys and tackle, that would hoist the blocks some thirty feet high and more.

It was a good time to build. The winter of grain had been planted now for over two months and harvest was another five months away, so the oxen were free and could pull the cut stone down the mountain. Proxenos’s craftsmen, a hundred or so in the army, who had worked at Thespiai and advised the builders of Mantineia and Megalopolis, brought from their packs drawings of arches and battlements—as if they had just inked them—and paired off with Messenians to ensure the walls went up straight according to their plumb lines. Now Ainias took up his dead friend’s scrolls and with Epitêles and Epaminondas held parley with the leading helots. Beside the Athenian helots that had come with Alkidamas, there were Doreios, Tisis, and Lelex, who spoke for all, though it was Nikôn who claimed preeminence by having done the most fighting against the Spartans. And, of course, he had made the long run to Helikon to fetch Chiôn and had rescued the corpse of Erinna. He now stepped forward. “We are the leaders of the Messenians. At least until we elect our archons. We’ll vote once the walls are up. Our Athenian helots are drafting the laws. So we are ready to build our city. You, Ainias, tell us of our plans. We want to cut stone. The sooner new Messenê is up, the sooner you go home. We want you home by the end of the year’s fifth month for your wheat harvest this spring as much as you do.”

Ainias looked at Proxenos’s master plans that he had gone over for a year, recently dirtied, wrinkled and torn a bit, as though Aritomenes had sketched them at the dawn of the polis. “Look here at these ancient worn scrolls. They say that the wall goes up thirty feet high at the towers, twenty high on the ramparts in between—the tallest in Hellas. It runs thirty stadia from the backside of Ithômê’s crown. Then it takes in the crest of Eva to the valley. Look for the guide points. Right here on the mountain. That’s where we put our northwest corner. All the holy ground to Asklepios and Artemis are set aside—and marked up here.”

Then Ainias tried to remember more from all his long talks with Proxenos about this third and best of his citadels, and so went on. “My men are cutting out the traces of the walls with spades. Only a city this big can have your herds and crops inside the walls, along with your houses and temples. All will be out of the Spartans’ reach, but with more inside your walls than either at Mantineia or Megalopolis. You can farm or vote or bathe inside, and care little whether ten or ten thousand Spartans are outside your walls. We put towers on every rise, like the scrolls of Aristomenes tell us, forty and more—and more of them square than round. Yes, four gates, one in each direction. But our busiest entry will be the east one, facing our sister-polis in Arkadia. There we will have a courtyard and swing doors higher than any at Mantineia. Its lintel—well, it will weigh far more than the Cyclopes’ work at Mykenai. Just watch when we slide that stone down the mountain. It will take forty oxen to pull, five hundred men to hold tight the ropes behind.”

Then Pelopidas walked up and warned the leader of the Messenians what to expect this spring. “You can say these plans were buried in sacred pots and come from your hero Aristomenes, or we can say they were the work of Proxenos who died on the Eurotas. It matters nothing to me. All we care is that ramparts go up and go up now. We have only three months for you to build the walls, and for us to keep out the Spartans before their spring campaign seasoning starts and maybe as late as Homôloios. Epitêles promises us a few more days for his Argives. He claims that he followed us to Messenia and will lead us out of here—the last to come and the first to leave. At night Alkidamas’s Athenians give you the laws and constitution. Listen up. You have no choice. The Thebans did not come south to set up an oligarchy. But we don’t want rule by the ochlos either. We kill the first looters we see, hang ’em up on the scaffolds we will. Epitêles has already done that. You bring Spartan hostages to us, no more killing of captives. Fix your own affairs by vote of the people—but only after we leave. Until then Epaminondas is your king. Don’t forget it. If you wish to eat, you better have the walls up before the barley harvest—otherwise you can chose between eating or dying in the open field when Agesilaos brings his Spartans over the mountain.”

For the next month, the helots cut stones at dawn with iron saws and then put them on carts to be guided down the mountain to the trenches. There, all night long, the forges turned out thousands of iron clamps for each day’s work. The fire men kept molten lead in huge iron pots to seal the joints from rust. The Messenians on the rising walls quit only after the lighting of the torches, even as the days lengthened and the spring equinox approached. While the men cut and stacked and the women cooked and weeded the fields, Epaminondas and his Thebans patrolled the countryside. They killed another four hundred Spartan holdouts, making two thousand altogether now dead from among the Spartan overseers and half-helots. Epaminondas knew the number because Ainias wrote the count on a vast scroll and posted it each day on a wood pillar next to what would be the Arkadian gate. No one counted how many Messenians Epitêles executed, for he hung up outlaws and thieves well beyond Ithômê, down the Alpheios and all the way to the sea.

But Epaminondas himself had also strung by the heels another eight hundred Messenians, looters and cutthroats who would neither work nor let those be who did. Most were Spartan inside anyway, but not all. The bodies of the murderers and thieves swung in the winter cold afternoon breezes with placards around their necks APEKTENON or EKLEPSA—“I murdered” or “I stole”—followed by APETHANON and “I died.” Some Messenians worried that they had exchanged the executions of Kuniskos for those of Epaminondas. Epitêles talked of his killing in camp at night while Epaminondas kept quiet. “It took us a hundred years and more at Argos, and we started as free, better men than these man-foots. Why do we think that those who were slaves will be masters of themselves and vote? Even if they vote, what’s stopping these hide-wearers from stealing money from the rich and voting themselves all sorts of free this and free that—the way they do it in most of our democracies?” Then he turned gruff. “Let’s find this Nikôn fellow, or maybe Lelex over there, give him some spearmen. Let him sit high in a castle on their new acropolis and like a good tyrannos run things until these people learn the rule of law. Before you have a Perikles—and I don’t see any here—you need a Solon a hundred and more years earlier, or better yet a Peisistratos or Pheidon. You can’t smooth a road without a hard rock bed underneath.”

Epaminondas laughed at the brute, but sensed also that he was a keen judge of the polis, having survived the killer gangs at Argos to come out on top. “Maybe. But babies can’t walk, yet at five they run faster than those in their seventh decade. Hellas has lots of democracies, my dear Epitêles. But they are old and tired, and need these toddlers and crawlers to keep us young and remind us what we once were. We gave them freedom, and they in turn have saved us from what we might have become, new barbarians of leisure and affluence who won’t put a toe outside of our city gates if there is a cloud in the sky. Now freedom is theirs to keep or lose. Either way it does not detract from our gift.”

Epitêles did not back down. “I and my Argives, we feel no better or worse from freeing them, and hardly think their freedom is a gift. Sparta is weak. Finished as we know it. She has no farmers to feed her phalanx, and won’t march out of Lakonia, at least for a while. That is good enough for me and mine. These helots can do what they like.” Epitêles laughed and for the next few days kept patrolling with his guard to hunt down more thieves who were stealing from the bread carts next to the scaffolds. He knew men by nature to be bad. They would kill and worse if they were not tired from work or scared of punishment. It was not in his nature to build, so he did what he knew best, he punished and hoped he killed more guilty than innocent—and worried little when he did not. “These Thebans can free anyone they please. But then who can’t do that? But they have no idea how to knock heads and keep these half-tamed on their leashes. Zeus in heaven, I think these Boiotians want to be liked rather than feared.” That the helots slacked off from the walls was of no real concern to Epitêles, other than as reason enough to kill those who were probably stealing rather than working. When enough were executed to discourage the no-goods, Epitêles would head home to Argos and the hard life among the murderous factions there. And so he did soon, and passed out of the history of the Hellenes.

Epaminondas thought he had Epitêles right when he had said of him, “Don’t wonder that he will leave us soon, but instead ask why this man in fur has even come. He is a warrior, one who wakes up in the morning promising to cut down Spartans and goes to bed each night in lamentation that he has not killed enough of them. We won’t see his like again in Hellas. He’s the good coin side to Lichas, though both are at home killing and so more alike than we think. Maybe our Chiôn, if he lives, is a third who could join this cabal of Aiases. But for now thank our One God that Epitêles was on our side.”

The friends of Erinna were also hunting down Spartans with Nikôn’s old band, always on what they claimed was the scent of a live Kuniskos. Still, they kept their distance from the trails in the uplands of cloudy Taygetos in fear of the man-animal—wolf, bear, panther or whatever he was supposed to be—that killed wayfarers. As the walls reached their sixth course, and the buds swelled on the fruit trees, all gave up on the Spartan stragglers—except Nikôn, who would not believe that Gorgos, the killer of Erinna, was dead and so went out after his ghost each morning. Finally, when the grain stalks bent, and the night frosts quit as the top courses were laid on the northern sections of the walls, he came late into the camp of the Boiotians.

“Gone. I know that now. Nêto must be long dead. But her killer Kuniskos I wager lives in the wild. He’s in the high pines, Mêlon. Your Gorgos—he has gone to the highlands. We hear that from some of those Spartans who are left on Taygetos, thinking Agesilaos will come back yet. But both banks of the Alpheios are now free and wide open and our boys are throwing their Spartans and their friends off our lands all the way to Elis in the north. Only a few grandees remain on their estates, lackeys of the Spartans, but we will get to them by the time the grain droops.”

Mêlon scoffed at Nikôn. He thought all of his Helikon people were now dead—his Nêto, along with Gorgos and Chiôn. All were gone to join Lophis. “Gorgos? He’s dead. Gone to the other shore, you mean, to meet the killers and robbers in the gloomy pools and pits of Tartaros where he belongs. How could he have escaped when his compound was said to be surrounded and his men hunted down? Nikôn, remember that the ghost you are hunting is only one man. Just one old Gorgos you run after. I wager he was surely run down amid the mob of fleeing Spartans—and forgotten in the carnage. I wish he were alive, so I could kill him five times over for his taking of Nêto.”

Nikôn raised his tone. “No, no. I sense it, even if the Spartan rumors are false. The soul of Nêto speaks to me, warns me of our danger. Gorgos at least lives. He’s alive but gone from here. He’s with Antikrates. Both are fated to no good unless we kill them now. They will lead an army against new Messenê. Ask the souls of your Proxenos and our Erinna; they’d be alive now if those two were dead. Doreios and I will go back out, one last time, and scour the valleys from the altis at Olympia to the summit on Taygetos. We can smell him from here. I will come back before Epaminondas leaves with news of your Gorgos or the head of our Kuniskos.” Nikôn went back up to Taygetos and all word of him went as well.

The builders from Thebes had taught the helots how to cut and dress stones, and how to swing their block and tackle over the walls’ rise with cranes mounted on oak beams. After the bloody work of Epitêles, there was no need for patrolling any more for bandits as spring came on, and the blue lupin of the month of Agriônios began to bloom amid calm. The helots stacked their stones, and it was agreed that the Spartans were all either dead or on the other side of Taygetos. Ainias sat atop the first tower and with a clay-baked cone barked out orders to those below. Epaminondas was drilling Messenian hoplites and teaching them the spear work of the phalanx—just in case Agesilaos came before the seventh or eight circuit was finished.

Alkidamas had reclaimed his hostage servant Melissos. The boy, for all his tough talk of armies and killing, was quieter as he took in the rising walls of Messenê—as if the stones held him in a trance and were no longer ramparts to copy, but almost had voices that spoke to him about the power of democracy. He, like Ainias, had thought the helots would only kill and loot, but was learning that they were better wall builders than the men even of Mantineia and Megalopolis—and wondered why the Spartans themselves could never build a citadel like Messenê. Alkidamas and Melissos took Mêlon and Ephoros up to the high perch of Ainias, where the five could see the entire circuit of the new polis and the terraced fields of the spring-green valleys beyond. Off in the distance they could spot Epaminondas at dawn, coming back into the valley of Ithômê, after a final march from Pylos by the sea with his new army of Messenian hoplites. They saw the outline of an entire city—the people of Messenia in constant motion, up and down Ithômê, as walls rose higher by the day, the towers elegant with dressed stones and polished embrasures. Pelopidas’s men were leading hundreds of teams of oxen, bringing down the latest batch of gray blocks from the mountain crest. Alkidamas pointed in every direction, as if he were charting the stars, in a slow methodical circle. “What are we to call all this, my conspirators in democracy? Has any in Hellas ever seen men working on through the dark—and yet back sweaty as well by the sunrise? No wonder the men of Sparta ate well with slaves like these. But how much harder they work when their fruits are their own. They are Hellenes all along, better than any of the free Peloponnesians.”

Ainias kept pacing around the parapet, unsure himself whether to be proud over Proxenos’s city or angry that in his mind it rose so slowly—or madder that he was here at all. But for now, he was confident that the helots would at last shackle the Spartans and keep them home for good. “There is a natural law, Alkidamas, at work, that always winnows out the chaff from wheat. So now with these fields and stones, all the Hellenes can see cities of the Spartans and Messenians side-by-side, and determine who are the better folk after all.”

Alkidamas laughed. “So Ainias is now won over to our side? The good cities are the work of the dêmos, just like when our Boiotians settled all their own affairs. What has oligarchy ever brought Hellas? If we are in the age of stone, it is because these vast new cities marshaled the people, who alone decide how it will protect itself. It is the people, always the people who both loot and yet alone create lasting cities of stone.” Ainias ignored him. But Mêlon was troubled hearing that praise of the dêmos, inasmuch as he was in deep thought about Nêto and Chiôn, and wondered what his son Lophis had died for. In this new age of Hellas, where walls and democracy made all alike, there were no longer to be men like the son of Malgis, Epitêles, and Ainias—and, if the truth be known, Lichas too, who had warned them all of what they had done at Leuktra in the parley after the defeat of the Spartans. There would be no more Chiôns either? No, the age of the hoplites, of a few exceptional men in bronze, who would decide the fate of states in an afternoon of hard war, was now over—destroyed by a few exceptional men in bronze. Perhaps Alkidamas was right after all about the good future ahead for the helots, but in a fashion he hardly imagined. The people had their bellies full of war and the songs of battle, and the armored men who owned land and could alone afford bronze. So they had built themselves walls to avoid fighting, at least fighting in the fashion of hoplites and phalanxes. Perhaps the people would stay snug in their high stones, and settle their quarrels with the new machines that flung iron arrows over the ramparts, or draw on the book knowledge of Ainias and Proxenos how to mine, and countermine—how to do anything other than march to the sound of crashing wood and bronze. What would the stone-bound do if they met folk like Melissos and his Makedonians, his tribes from the north who were weaned on horses and carried on their belts bright badges that marked the number of men they had cut down in battle?

Mêlon woke up from his day trance and noticed that Alkidamas and the dour Ainias had been talking the entire time as they moved all over to the highest ramparts of a section of finished walls. Ainias now continued: “Come over here, Mêlon, we can talk and I can point to you the stones as they rise. You can see that by month’s end all twenty towers are finished. Look at the streets of the city. They’re all paved with flat stones and drains, and all in a grid, with corners square. Look at the city of Proxenos. He drew it from the mind of Hippodamos, who got his odd and even streets, his straight lines from the voice of the One God himself. And the childish Messenians followed his plans only on the silly myth they were not really Proxenos’s ideas, but those of their ancient hero Aristomenes who supposedly three hundred years earlier had prophesied that his people would build a city far grander than the Spartan hill and then buried his plans in a jar. When a Spartan goes to battle, he leaves a mess, a labyrinth of clutter on his acropolis. When a Messenian rushes out to meet enemies, he now runs down a broad way to a square agora. His phalanx falls together in the manner in which his city was planned, his field surveyed, and the seats of his council hall divided up. Every hoplite, every house, every farm, every bench will be equal to another, none greater, none smaller—daily reminders that there are no more Spartans, no more harmosts, only the square corners of square thoughts.”

By the fourth month of the new year, the capstones of more than half the walls of Messenê were nearly finished—even though the Argives and Boiotians had forced the Messenians to add ten stadia to ensure that the circuit ran up the slopes to the crests of Mt. Ithômê. Rumors of a Spartan army on the move against the new helot state proved fantasy—as did more stories about Nêto and Chiôn alive on Taygetos hunting down Gorgos. In truth, Agesilaos was still hobbling along the banks of the Eurotas and waiting for his Spartan stragglers to get back home safely over the high passes of Taygetos as the spring snow melted and with it the last guard of the Spartan-held Messenia, never to return. When King Agesilaos finally drew up his muster lists, he discovered that few of his Spartans in the west had made it back alive from Ithômê. Shepherds had brought him more news of the arrival of the wild shape-changer—not a god, or even a half-god like Herakles, but a man-wolf, or mountain bear, yes, more a man-bear—hunting down all winter long the Spartan packs in the mountains, and hanging the kryptes by their capes. For some he was surely some daimôn of legend. Perhaps he was wily Sinis, who tied his prey between two bent pines and watched the trunk split the legs, now come up from Epidauros to find new prey. Others swore they had seen the killer Skirôn who tossed his victims over the gorges of high Taygetos. Many thought the monster was grizzled and lame Korynetês of widows’ tales come back alive who smashed the brains of wayfarers and shepherds with his iron club. The helots, however, knew him as the Great Deliverer, the shape-changer that ensured no Spartan dare return home over the passes of Taygetos. Nikôn, who alone went up to the summit and who alone came back, knew the man-bear as the real bulwark of Messenia, the demon that came late and from nowhere and had so scared the Spartans that they dared not muster to stop the rising walls below. And yet as for Nikôn and his rangers, the monster let all of them be.

Lichas, still on the east side of the mountain in Sparta, promised to send his best of the Spartan royal guard up to Taygetos to find this daimôn. The Spartans would drag him down—demon or not—to the gorge and throw him onto the rocks. If he were some enormous bear or freak wolf-dog, he would surely bleed; if a ghost they could get priestesses to cast spells and incantations to send him back into the crevices below. If a black god in human shape, Lichas would wrestle him down to Hades. So he sent word for Antikrates and the sword man Klôpis, and tall Thibrachos as well, and the mother of Thibrachos, fiery Elektra his latest wife whom he bedded in her tall tower despite her four decades and more—all eager to kill helots and their friends and mount the severed head of this man-bear monster among the trophies of the Menalaion at Sparta. The best of the Spartans would kill the man-bear. Agesilaos would see that the passes were open and the silly stories of old women about monsters and demons were no more than the babbling of the unhinged. Then the way back to Messenia would be open.

Even as the small band of Spartans plotted to find news of Kuniskos and scout a way for Agesilaos into Messenia, the time of departure for the army of Boiotians neared. The walls were finished, and there grew talk against Epaminondas, both among his own men who wanted to leave immediately and among the freed helots who almost had their circuit and wished the foreigner gone. A free people, their new demagogues proclaimed in the assembly, no longer wanted to feed three myriads of “friends.” Anyway, the camp of Epaminondas stank and fouled the field near the Arkadian Gate. The Boiotians drank at night and sang of their spearing in Lakonia and took all credit for the end of Sparta, and laughed at the helots for their pretensions of being men of the polis. Too many of them spoiled the sanctuary of Asklepios and were bathing in the holy waters of Klepsydra.

As he readied to leave, Epaminondas wished to remind all of the good done, in this his first and last public address to the helots in the half-finished stadium of the Messenians. All the citizens of the new polis filed into the stade-long course at the south of the city, near the Messenian Gate. There were forty thousands on its earthen seats, and maybe as many more on the field and on the walls above. Epaminondas spoke in front of a new iron statue of himself near the entry to the stadium and an altar of thanks that the women of Messenia had raised for the Boiotians and Argives.

“A great plague has passed, men of Messenê. Those who crossed their borders to enslave others are themselves surrounded. The Spartan hunters have become the hunted. Yet I remind you only that freedom won after these hundreds of years can just as easily be lost again in one—should the nerve of your newfound democracy fail and you let your shields slack to your knees. It is the nature of all men in peace to become soft and scoff at the prior hard work of their fathers who gave them such bounty. Beware the real enemy is the smoother second thought that always mocks the rougher first. You tire of us, we of you. Such is also the way of peace. So be it. Enjoy these last days of spring. Soon when your hair is white or gone, the remembrance of these great days alone will give you comfort when all else is gone.”

This was no audience of jaded Thebans who usually hooted and pelted their speakers with fruit, but one of recently freed men who slowly grew silent in renewed appreciation of their liberator as he finished and would soon depart. Now this Epaminondas took them all back to the first days when he and Epitêles came off the mountains, and the Spartans fled in terror at the mere rumors of their descent, and the helots and their liberators were one.

“We are seeing the new age of walls under holy Ithômê, worthy of Mykenai or Troy of old when only the Cyclopes could build such stout ramparts as these before us. But men of Messenê, do not trust solely in such rock or oak. It is not towers or the new machines that cast stone from afar that keep men free. Only the right arms of those willing to meet the enemy shield to shield and spear to spear will keep the Spartans out. Now the time comes for us to return to our families in the north below Helikon and Kithairon. Farewell, men of Messenia, and do not forget what those heroes of Hellas did on your behalf to make you the best men of the Peloponnesos.”

A roar followed the general’s finish. Even the dour Pelopidas and Ainias were struck by thousands of these folk who stood on the walls and towers shouting in their trust of Epaminondas—this tiny man who in a few days after all would be put on trial for his life when he arrived back at Thebes. The great war for Messenia was at an end. The great war to live in safety as free people had begun. All that was left was the cleanup, and the muster of the Boiotians as they broke camp. For one hundred and twenty days the men of Epaminondas had worked without a break, despite the furor of Epitêles and the whines of the Sacred Band. Vineyards and orchards were to be planted inside the walls, and two thousand plethra of barley and wheat. Five thousand head of stock roamed in open pastures beneath the walls. The grape land was black heavy land, watered by ten great springs on the slopes of the mountain—all taken from the Spartan clan of the royal Agiads whose helots had sent its harvests for four hundred years back to the royal family of Sparta.

In thanks for the health of the dêmos, the Messenians had laid out a temple to Asklepios, the healing god. In front was a marble statue of Nikê, the goddess of Victory, which they had erected to honor their Nikôn, now stratêgos of the Messenians, with his deputy Doreios, the first archon of the people. Inside the half-built temple was a model of clay that Ainias had made from the maps of Proxenos. At last the city and this model were one. There were thirty stadia of walls, ten feet thick, fifteen high, all faced with gray limestone and filled with rubble in between. The courses ran up and nearly encircled the crest of tall Ithômê. Thirty towers—two square for every round—rose thirty feet. They had put two stories in them with embrasures below their sloped roofs and, thanks to Ainias, the new belly bows aimed out the windows. Four gates, the tallest, the Arkadian in the north, shut the city tight. They left standing in the agora the hated log house of Kuniskos, a reminder to their children not born of their past bondage and the cost to free Ithômê from the likes of Antikrates and his Gorgos. His timber stakes were red with blood and gore and Nikôn had ordered the horrid poles stay up—until the head of Kuniskos could become their last trophy and they could be burned.