CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

“Harris, you’re on guard duty,” Lector said, as I climbed the ladder out of the bunkers.

“Aye,” I answered, fighting back the urge to say more. I watched Lector swagger back to the front of the platoon, then switched interLink frequencies. “Lee, you there?”

“Sure,” Lee said.

“Lector just gave me guard duty.”

“That should be dull,” Lee said. “Yamashiro will be light-years from here by now.”

“If he was ever here,” I said.

“Of course he was here,” Lee said. He clipped his syllables as he spoke, something he did when he felt irritated. I knew better than to argue.

Thick forest covered the foothills ahead of us. Trees with green and orange leaves, so brightly colored they looked like gigantic flowers, blanketed the countryside. “Gather up,” I called to my men, as we started for the forest.

The foothills stretched for miles. Beyond the hills, I could see the vague outline of tall mountains against the horizon. Somewhere between the forested hills and the mountains we would catch our enemy. “Let’s roll,” I said, after organizing my men.

Our course took us through the forest. The trees and boulders would have provided the right kind of cover for guerilla attacks. I scanned the landscape for heat signatures, but the trunks of the trees were ten feet in diameter. The rocks were thick and made of granite. I could not read a heat signature through such barriers. The light played against us, too.

Rays of sunlight filtered in through the trees. Bright, hot, and straight as searchlights, the beams of light looked like pillars growing out of the floor of the forest. And they were hot, as hot as a human body—nearly a hundred degrees. When I looked at one of the rays of light with my heat vision, it showed orange with a yellow corona on my visor, the same signature as an enemy soldier. I pinged for snake shafts and found nothing, but that did little to calm my nerves. Fortunately, our scouts located enemy tracks. Hundreds of people had fled the bunkers, trampling ferns and shrubs as they rushed through the trees. Tracking the escapees posed little challenge, but the wilderness gave us other headaches. The overgrowth slowed our ATVs. Obviously, Harriers and gunships were out of the question. We had to send scouts ahead on foot. Five of our scouts did not return when we broke for camp that evening.

We stopped in a mile-wide clearing that would be easy to guard. At night, Little Man cooled to a comfortable sixtyfive degrees. When I scanned the serrated tree line with heat vision, it seemed to hold no secrets. I saw the orange signatures of forest animals moving around the trees. Every few hours, at uneven intervals, a gunship traveled around the perimeter of the clearing. I sat at my guard post, hidden behind a hastily built lean-to made of logs, clods of grass, and rocks, peering out across the flatlands at the trees. The night sky had so many layers of stars that it shone milky white. I realized that not all of the stars were in our galaxy. We were at the edge of known space. A gunship rumbled over the treetops, its twin tail engines firing blue-white flames. Moonlight glinted on the ship’s dull finish as it circled slowly across my field of vision. Traveling at a mere twenty miles per hour, it moved with the confidence of a shark circling for food. Switching the lens in my visor to heat vision, I watched animals flee as the gunship approached. A stubby bird, built a bit like an owl but with a seven-foot wingspan, launched from the trees and flew toward me. I could not see the color of its plumage with heat vision, and I could not see the bird at all when I switched to standard view. Guard duty left me with plenty of time to roll evidence over in my mind. I did not think we were there to massacre Japanese refugees from Ezer Kri. They would not have had time to build the complicated bunker system on the beach.

The Morgan Atkins Separatists seemed a more likely target. I did not know how the Japanese could have gotten off Ezer Kri. They never could have traveled this far. I did not know what the Mogats would want on a planet like Little Man, but I knew they had transportation. They had their own damn fleet. Still, why would the Mogats colonize a planet that was so far from civilization? As I understood it, the Mogats never populated their own planets. They sent missionaries to colonize planets and attracted converts. But there was nobody to convert in the extreme frontier.

Just like Lee predicted, the night passed slowly.

We found three of our missing scouts early the next morning.

Packing quickly before sunrise, we continued through the woods. The trees in that part of the forest stood hundreds of feet tall. They stood as smooth and straight as ivory posts, with only a few scraggly branches along their lower trunks. Perhaps that was what made the scene so terrible—the almost unnatural symmetry of the primeval woods.

Walking in a broad column, we turned a bend and saw two dwarf trees with thick, low-hanging branches that crisscrossed in an arch. These trees stood no more than forty feet tall, but the spot where their branches met was considerably lower. A wide stream of sunlight filtered in around them, bathing them with brilliant glare and shadows.

Three shadowy figures dangled from the branches like giant possums. A quick scan of the forest floor told us that the bodies were our missing scouts. Each man’s armor and weapon sat in a neat pile beneath his lifeless carcass.

We knew our scouts had died by hanging even before we cut their bodies down. The enemy had captured them, stripped them of their armor, and summarily executed them as war criminals.

“I want those trees destroyed,” a major ordered, as we cut down the bodies. A demolitions man strapped explosives around the trunks. As we left, I heard a grand explosion and turned to watch as the forty-foot trees collapsed into each other.

The enemy had time to leave trackers along the trail, but trackers were ineffective in such rough terrain. They also left mines and a few snipers behind. The mines were useless; we spotted them easily. The snipers, however, used effective hit-and-run tactics as they targeted our officers. We began our march with fifteen majors and three colonels. By nightfall, two of the colonels and six of the majors were dead. When I saw McKay late that afternoon, he was surrounding himself with enlisted men.

“You holding up okay after that all-nighter?” Vince’s voice hummed over the interLink.

“Bet I’m asleep before anyone else tonight,” I said, unable to stifle a yawn. Regrettably, Lee had not contacted me on a direct frequency. “You’d lose that bet,” Lector interrupted.

“You’re on guard duty tonight.”

“Sergeant, you cannot send a man on guard duty two nights in a row,” Lee said.

“Are you running the show now, Lee?” Lector asked. I heard hate in his voice.

“Back off, Vince,” I said.

“Wayson . . .”

“Stay out of this,” I hissed.

On a private channel, Lee said, “I hate specking Liberators.”

So did I.

We reached the edge of the forest in the late afternoon. There we discovered that our air support had been busy.

The still-unidentified squatters had built a town large enough for a few thousand residents just beyond the woods. It had paved roads and prefabricated Quonset-style buildings. If they had put up flags, the place would have looked like a military base.

Our fighters struck during the night, shredding the town. I saw shattered windows, collapsed roofs, and melted walls. What I did not see was bodies.

“Sarge, do you think this was their capital city?” one of my men asked. I did not answer. “Fall in,” I said over the platoon frequency. “Get ready. If we’re going to run into more resistance on this planet, it’s going to start here.”

The town was also a likely place to find out the “squatters’ ” identity. We would find computers in the buildings. Perhaps we would find more. With our guns drawn and ready, we organized into a long, tactical column with riflemen and grenadiers from Lector’s platoon guarding our flanks. We waded toward town. Lee’s squad took point, moving cautiously in a group that included a rifleman, a grenadier, and a man with an automatic rifle. They moved in slowly, pausing by fences and hiding behind overturned cars. With every step it became clearer that the enemy had abandoned the city before our fighters attacked.

Most of the cars lay flipped on their sides, their front ends scorched from missile hits or fuel explosions. Smoke and fire had blackened the windows of several vehicles. I kicked my boot through one car’s windshield in search of bodies but found none.

The first building we passed was a two-story cracker box with only two windows on its fascia. The facade was untouched, but a laser blast had melted a ten-foot chasm in a sidewall. Metal lay melted around the gaping hole like the wax bleeding from a candle. The heat from the laser must have caused an explosion. The windows of the building had burst outward, spraying glass on the street. Though I could not feel the glass through my boots, I heard it splinter as I walked over it. The firefight began with a burst of three shots. Bullets struck the ground as Lee and his rifleman stepped around a derelict car. The bullets missed. Lee and his rifleman dropped back for cover and returned fire. The enemy had taken position in the ruins of a building that might have been a latrine. Pipes wrapped the sides of the small structure, and its walls were thick. The gunmen opened fire. I could see muzzle flashes.

“Harris, report,” Captain McKay ordered.

“We’re under fire, sir,” I said. “It seems like it’s just a few men hidden in a latrine. We should have the situation under control shortly.”

“Pockets of resistance,” McKay said. “They’re trying to slow us down. I’m getting reports of small firefights on every street. Let me know when you have the situation handled.”

“Aye, sir,” I said.

“Lee, how are you doing up there?” I asked, changing frequencies.

“These guys can’t shoot for shit,” Lee said. “Twenty yards away, tops, and . . .” He stopped talking as a long volley of shots ricocheted off the ground around him.

Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Five distinct reports, single shots from an M27 that cut right through the clatter of machine-gun fire. Lector’s riflemen had flanked the enemy, slipped into the building behind them, and shot them in their hiding holes. One of the riflemen walked to a window and signaled that all was clear. His strategy was a textbook tactical advance.

“Enemy contained,” Lector called in, over the interLink.

I spotted a stairwell that ran below ground on the other side of the street. “Lee, take my position.”

“Where are you going?” he asked as he let his squad walk ahead.

“I see a door that needs opening,” I said as I peeled off from the column with two of my men in tow. We ran across the street and took cover behind a brick wall.

The stairwell looked like it might lead to a bomb shelter or a subway station. It was wide enough for three men to run side by side. One of my men did a run by, peering down the stairs, then rolling out of range. He stood and took a position at the top of the stairs, signaling that the entry was clear. There were no windows in the concrete walls lining the stairs, just a seven-foot iron door with an arched top. I ran down the stairs and hid by the hinged side of the door. One of my men took the other side. As I pulled the door open, he counted to five then swung in, sweeping the scene with the muzzle of his rifle.

“Clear,” he said.

I followed him through the door.

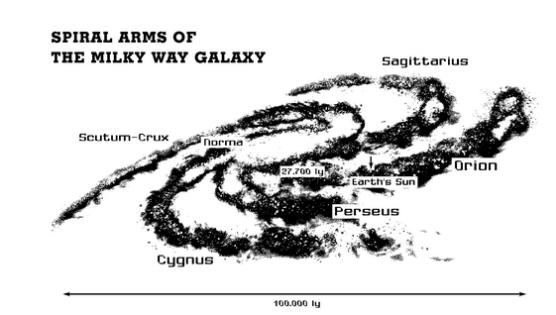

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” the third man in my party said as he followed us into the structure. We had entered a tactical command room. File cabinets lined the walls. Several maps lay open on a table in a corner of the room. I checked the maps for traps, then leafed through the stack. The first map showed the names and locations of every military base in the Scutum-Crux Arm. The next map showed a complex system of dots and lines overlaying a map of the galaxy. A sidebar showed an enlarged view of the Sol System. When I saw a red circle surrounding Mars, I realized that it was a map of the broadcast network.

“Don’t touch anything,” I said to my men. It was too rich a trove. It had to be rigged. We would leave it for the experts in Intelligence.

Captain McKay told me to nap while the rest of the men set up camp. I found a shaded corner between a tree and a stone wall. Removing my helmet, I lay on my side in the cool grass and let my mind wander. I thought about that underground map room with its diagram of the broadcast network. There was nothing top secret about the disc locations, but seeing them charted in an enemy bunker made me nervous. Those discs served as the Unified Authority’s nervous system. An attack on them could bring the Republic to its knees.

But why would anybody want to bring the Republic to its knees? The Senate allowed member states tremendous latitude. Breaking up U.A. infrastructure would end the ties of humanity that connected the various territories. Take away the Unified Authority, and the outer worlds would be forced to survive on their own.

In my mind’s eye, I saw myself walking along a long corridor. Imagination turned into fitful dreams as I reached the first door.

Night had fallen by the time Lee woke me for guard duty. He led me to the edge of town and pointed to an overturned truck. “That’s your station for the night,” he said. He slipped me a packet of speed tabs. “I borrowed these from the medic. Don’t use them unless you need them,” he said. I took my position hiding behind a crumpled-up bumper. Though I needed more sleep, I liked the solitary feel of guard duty. It gave me a chance to consider the day and play with ideas in my head. I had been on duty for two hours when Lector came to check on me. “See anything, Harris?”

“No,” I said.

“Keep alert,” he said. He lit a cigarette as he turned to leave.

“I don’t get it,” I said. I was tired and angry. I heard myself speaking foolish words and knew that I would later regret them; but at that moment, I no longer cared. “What the hell did I ever do to you?”

Lector listened to my question without turning to look at me. Then he whirled around. “You were made, Harris. That’s reason enough,” Lector said coldly. “Just the fact that you exist was enough to get Marshall, Saul, and me transferred to this for-shit outfit.”

“I had nothing to do with it,” I said.

“You had everything to do with it,” Lector said. “You think this is a real mission? You think we are going to capture this entire planet with twenty-three hundred Marines? Is that what you think?”

I did not know what to say.

“They’d forgotten about us,” Lector said. “Saul, Marshall, me . . . Nobody in Washington knew that there were any Liberators left. The brass knew about Shannon, but there was nothing anybody could do about him. Klyber kept him nearby, kept a watchful eye on him. Nobody could touch Shannon with Klyber guarding him. As far as everybody knew, Shannon was the last of us.

“Then you came along, Harris—a brand-new Liberator. You weren’t alone, you know. Klyber made five of you. We found the others. Marshall killed one in an orphanage. I killed three of them myself. But Klyber hid you . . . sent you to some godforsaken shit hill where no one would find you. By the time I did locate you, you were already on the Kamehameha .

“I . . .” I started to speak.

“Shut up, Harris. You asked what’s bothering me, now I’m going to tell you. And you, you are going to shut your rat’s ass mouth and listen, or I will shoot you. I will shoot you and say that the goddamn Japanese shot you.”

I believed him and did not say a word. I also slipped my finger over the trigger of my M27.

“The government hated Liberators. Congress wanted us dead. As far as anyone knew, we were all dead. Then you showed up. I heard about that early promotion and wanted to fly out and cap you on that shit hill planet. I would have framed Crowley, but Klyber transferred you before I could get there.

“Next thing I know, you’re running missions for that asshole Huang. Shit! Huang was the reason we were in hiding in the first place. As soon as I heard that you’d met Huang, I knew we were all dead. Once he got a whiff of a Liberator, he would go right back to the Pentagon and track down every last one of us.

“And here we are, trying to take over a planet with twenty-three hundred Marines. This isn’t a mission, Harris, this is a cleansing. This is the last march of the Liberators; and if they need to kill off twenty-three hundred GI clones to finish us, it all works out fine on their balance sheets. Clones are expendable.

“You want to know what I have against you, Harris? You are the death of the Liberators.”

“Oh,” I said, not knowing what else to say.

“Now watch your post,” Lector spoke in a calm voice that made his anger all the more frightening.

“We’re pushing into that valley tomorrow. Whoever we’re hunting on this goddamned planet, we’ll find them in there.” Having said his piece, Lector turned his back on me and left. He tossed the butt of his cigarette behind him. The tiny, glowing ember bounced and slowly faded. Klyber had made five Liberators? Klyber had me sent to Gobi to protect me? It made sense, I suppose. When I thought of Booth Lector, I felt both sympathy and revulsion.

Tabor Shannon and Booth Lector shared the same neural programming, but it controlled them in different ways. Lector was addicted to violence and self-preservation. He was cruel and brooding. Shannon might have been a white knight, but I saw him as flawed. He lived his entire life on a quixotic mission to protect a society that despised him.

Earlier that evening, I had told myself that the Unified Authority bound mankind together. However, as I thought about it again, I questioned the benefits of being tied to mankind.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

Having slept for approximately two hours over the last two days, I felt sluggish and dizzy when Vince Lee led me back to camp. The ground seemed to shift under my feet, and I had trouble walking in a straight line. I considered taking the meds Lee had given me, but decided against it. Luding would keep me awake, but it would probably leave me jumpy when I needed a clear head. And I definitely needed a clear head. The officers monitoring our progress from aboard the Kamehameha did not wait for sunrise before sending us into the valley. There was no trace of sunrise along the horizon when we grabbed our rifles and set off.

Walking in squads of five, we left the town and started into the valley. There the terrain came as something of a surprise. I expected grass, trees, and gently sloping hills. What I saw was a glacial canyon with steep, craggy walls. A well-trampled path led along the side of the canyon. The trail was wide enough for a squad or maybe a platoon, but not an entire regiment.

Observing the scene from the rim of the canyon, using my night-for-day lenses, I felt an eerie shutter of déjà vu. It was like returning to Hubble. The thick layer of fog on the canyon floor only added to the illusion.

“At least we won’t need to go looking for the bastards,” Captain McKay said as he moved up beside me.

Switching to heat vision, I saw what he meant. About two miles ahead of us, hundreds, maybe thousands, of orange dots milled around the valley floor.

“Look at them,” I said. “Think that’s what’s left of the Japanese?”

“Obviously not,” McKay said. “Whoever they are, they’re waiting for us. They’re dug in tight, armed, and waiting for us. Remember when I asked you to watch my back? I know you’re beat, Harris, but if you have any Liberator fire left in you, get me out of this alive.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, though I had little hope to offer. If Lector planned on killing friendlies, his first bullet would have my name on it.

Our assault took place in three stages. As the sun rose over the far edge of the canyon, we “assembled.”

Our officers, the few who had survived the previous day’s snipers, surveyed the field and assigned routes to each platoon. From there, as the rising sun melted the fog on the canyon floor, we traveled down the steep walls. That was the next stage of the assault, the “attack point.” Then we fell into formation and made our last preparations.

The terrain was flat and empty. Jeeps, ATVs, and tanks would have been effective at that point, but nobody offered to airlift them in. Admiral Thurston wanted an infantry strike. With our light artillery preparing its positions, we started our advance.

A wide river must have once run across the valley. Its long, smooth, fossilized trail offered excellent placement for men with mortars.

Having left the artillery behind, we divided into two groups. The majority of the men formed a column that would attack the squatters head-on. One lone platoon would be assigned to move along the south side of the canyon and attempt to flank the enemy.

I was not surprised when I heard from Captain McKay. “Harris, your platoon is covering the flank.”

“Who signed us up for that?” I asked, though I knew the answer.

“Lector recommended you. He’s pretty much running this show. Everybody is afraid of him.”

“Are you coming with us?” I asked.

“No,” McKay said. He wished me luck and signed off.

A pregnant silence filled the canyon as the two-thousand-man column started forward. The squatters began firing long before the column was in range. Only snipers with special rifles would be effective at such a distance. The squatters had a few snipers, of course, but they seemed to be out of commission at the moment.

My platoon started its route just as our artillery units began lobbing mortars. The enemy had the tactical advantage of choosing the field, but our artillery soon battered their positions. I led my men in a fast trot toward the south edge of the canyon. Hidden by a slope in the terrain, we slipped forward undetected. As we closed in, I hid behind some sagebrush and spied on the enemy position.

The main column remained just out of range as the bombardment continued. Shells exploded, sending swirls of silt dust and smoke in the air. Any moment now the shelling would stop, signaling the column to pin the enemy down while we closed in beside them.

Before we could attack, the squatters retreated. They abandoned their position and ran. I watched them from behind a sagebrush blind—thousands of men running toward distant canyon walls. I thought they were running from our mortars, but that wasn’t the case.

Far overhead, another battle was taking place. Robert Thurston, the master tactician, had lied to us about everything. These “squatters” were Mogat Separatists; and while Little Man was not exactly Morgan Atkins’s Mecca, the planet was a Separatist stronghold.

Giving us bad intelligence, Thurston landed our forces by the Mogats’ weakest flank. With minimal air support and the element of surprise, we broke their defenses and chased their unprepared army. But reinforcements would soon arrive. Admiral Thurston, who viewed clones as equipment of no more value than bullets or tank treads, used us as bait to lure the Separatists into a counterattack. As we chased Mogats on the surface of Little Man, four self-broadcasting battleships appeared around the Kamehameha . Thurston barely managed to raise his shields before they opened fire. With the dreadnoughts battering her shields, the Kamehameha headed toward a nearby moon.

The army that joined the Mogats at the far end of the canyon outnumbered us five to one. Their tanks and jeeps were forty years old. They drove antiques, we had the latest equipment; nonetheless their antiques would be very effective against our light infantry.

The Mogat army wore red armor. Red, not camouflaged, no attempt was made to blend in. They poured down the rim of the canyon like fire ants rushing out of an anthill, their armor glinting in the bright sunlight. Our officers were alert. The column quickly collapsed into a defensive perimeter by taking shelter behind the side of the riverbed.

“Holy shit,” Lee screamed. “We’d better get down there.”

“Hold your position, Lee,” I said.

I frantically contacted Captain McKay. “Captain, I’m coming to get you out of there.”

The Mogats were at the bottom of the canyon and coming fast. Poorly aimed shells from their tanks and cannons hit the ground well wide of their mark.

“Do they see your position?” McKay shouted.

“I doubt it,” I said.

“Get your men out of here, Harris.”

From where I lay, about three hundred yards from the action, the battle seemed to take place in miniature. I saw our men hiding in the dirt and the enemy running forward. The enemy looked poorly trained, but that would not matter with their numerical advantage.

The Mogat gunners figured out the range and their shells began pounding the riverbed. I saw a shell hit a group of men, flinging their bodies in different directions. Back behind the brunt, our light artillery returned fire far more effectively, hitting the advancing sea of enemy soldiers time and again. It didn’t matter. There were far too many of them for a few shells to matter.

Squads of fighters and six destroyers raced to the Kamehameha ’s aid. In the distance, the Washington and the Grant, ironically the two ships Thurston used to defeat Bryce Klyber in their simulated battle, remained stationed behind the cover of the distant moon. They had slipped in unnoticed two days before the Kamehameha arrived.

Self-broadcasting is a complex process that takes time and calculation. Thurston’s ships counterattacked swiftly. Before the battleships could broadcast themselves to safety, Thurston’s Tomcats and Phantoms swarmed them. His destroyers arrived moments later, blasting the battleships with cannons that disrupted their shields. The Mogats had enormous ships, but their technology was forty years old, and they did not have engineers who could update it.

The surprise attack succeeded. Two of the battleships exploded before returning fire. The third staged a weak defense, managing to demolish several fighters and dent one destroyer before exploding. The last Mogat battleship turned and ran. The officers commanding the lumbering ship could not have hoped to outrun the fighters. They must have thought they could buy enough time to broadcast to safety. Closing in from the rear, a destroyer fired several shots at the battleship’s aft engine area. The ship’s rear shields failed, and several of its engines exploded just as it entered Little Man’s atmosphere.

The Mogats poured into the valley like a tidal wave. They would not need stealth or weapons to flank our two-thousand-man invasion force—it almost looked as if they planned to trample us. But U.A. Marines do not give up without a fight.

“What do we do?” one of my men asked as I returned.

“McKay ordered me to retreat,” I said.

Hearing that it was an order, my men immediately complied. Without a word, they turned and started back. Then Lee noticed that I did not follow. “Harris, what are you doing?”

“I want to get McKay out of there,” I said. “I promised I would watch his back.”

“Wayson, you have got to be joking,” Lee said. “Take another look. He’s probably dead by now.”

I crawled up for one last look. I doubted that he had died yet, but his time was probably just about up. The Mogats had closed in on our front line and overwhelmed it. On one side of the battle, a group of about fifty men formed a tight knot and charged the enemy head-on. The tactic they took gave them the element of surprise. They broke through the Mogats’ front line and pushed deep into their ranks. It was a gutsy move, but doomed to fail. As they fought their way toward an open field, they took more and more casualties. I did not stay to see if any of them survived the charge. In the center of the battle, the Marines put on one hell of a show. Our riflemen pinned down pockets of enemy Mogat soldiers and our artillerymen lobbed a continuous arc of mortar fire. Despite their efforts, there was no denying the superiority of numbers. By the time I turned to follow my men to safety, it looked like half of our invasion force was dead or wounded.

“Can we go now?” Lee asked, sounding anxious.

I did not want to leave. Whether it was programming or upbringing, my instincts were to fight to the end. I sighed as I climbed to my feet. “Okay, Marines, let’s move quickly!” I shouted, in my best drill sergeant voice. Most of my men were already a hundred yards ahead.

The air still rang with gunfire, but the amount of shooting had slowed considerably. By the time we reached the far end of the valley floor, I only heard the sporadic bursts. We sprinted for the path leading up the far wall. The path twisted, and it left us more exposed than I would have liked, but I thought it would be safer than stumbling up the steep slopes. By then we were several hundred yards from the battlefield. If we could just reach the top of the ridge, without being seen . . . “Stay low, move fast. Any questions?” I said to my men. I led the way, rifle drawn, shoulders hunched, running as fast as I could. If there happened to be a few enemy soldiers at the top of the trail, I thought I might stand a chance of picking them off. My lungs burned and my mouth was dry, but I had shaken off the fatigue I felt earlier that morning. The adrenaline rush of battle had woken me far more effectively than any meds ever could have. The muscles in my legs tingled and my head was clear as I continued up that dusty course at full speed. The path started at a gentle angle, no more than ten degrees. A few yards up, however, it took a steep turn. I felt fire in my calves and growled.

I no longer heard gunshots, but what I heard next was far more frightening: the whine of ATVs. Turning a bend in the path, I paused and saw four trails of dust streaking along the valley floor in our direction.

“Move it! They’re coming!” I shouted to my men. I swung my arms in a circle to tell my men to run faster, and I slapped three men on their backs as they ran past me. “Move it! Move it! Move it!”

The ATVs stopped a few yards from the base of the trail. As the last of my men ran past me, I saw four men climbing off their vehicles. They had rifles slung over their shoulders. “They’ll never catch us,” I said to myself as I turned and sprinted.

I was just catching up to Adrian Smith, one of the new privates who had transferred in while I was in Hawaii. He was a slow runner; I thought that I might need to stay with him to coax him on. That was what I was thinking as the bullet smashed through his helmet, splashing brains and blood against the side of the hill. The sound of the gunshot reverberated moments after Smith fell dead. Ahead, up the trail, three more men fell just the same way. A single shot to the head followed by the delayed report of the rifle. The men at the base of the trail never missed a shot.

“Everybody down!” I yelled. “Snipers!”

They were using our tactics. The snipers pinned us down. Across the valley, hundreds of soldiers were headed in our direction. If we did not get up the ridge quickly, we would never make it up at all.

“Lee, take them up the hill,” I called as I darted behind a rock.

“What are you doing?” Lee said.

“That is an order, Corporal.”

Below me, one of the snipers saw Lee get to his feet. He swung his rifle. As he trained on the target, I shot him with a burst of rapid-fire. All three bullets hit the sniper before he fell. Another sniper returned my fire. The other two picked off several more of my men. I crawled along the ground, steadied my rifle, and rolled to one knee. Two of the snipers fired at me before I could squeeze off a shot. The third hit another of my men. In the background, I saw the Mogat army. They were almost here. Ducking out of their sight, I lobbed a grenade. The blast kicked dust into the air. I rose to have another look, then ducked back down quickly. For some reason, the Mogats had stopped. Many were looking at the sky. Whatever had distracted them was not important enough to stop the snipers from taking shots at me. Three bullets zinged the ledge near my head.

I rolled onto my back, then I saw it—a dark gray triangle dropping quickly through sky. It looked like a capital ship, but capital ships were not designed to fly in atmospheric conditions. Whatever it was, the triangle left a thick white contrail in its wake. The smoke billowed out in tight pearls that spread and congealed into a smooth strand of cloud. At first, the ship fell straight down, then it managed to catch itself.

And, as it flew closer, I noticed that there were dozens of smaller ships buzzing around it. From where I lay, the scene looked like a hive of bees attacking a bear cub as it tried to run away. The valley seemed to shake under the echoing rumble of the big ship’s engines. The ship was dropping lower and lower. The fighters that surrounded the ship continued to pick at it with lasers and rockets.

“Harris, get out of there!” Lee screamed. “That thing is going to crash.”

Flames burst out of the front and rear of the ship as it dropped like a shooting star. A few bullets struck the ledge below me as I jumped to my feet, but I no longer cared. I sprinted as hard as I could, turning corners and skidding but staying on my feet.

The battleship slammed into the far end of the valley sending a shock wave, flames, radiation, and debris. Nearly one mile from the explosion, the shock wave hit me so hard that it tossed me through the air and into the canyon wall. The blast knocked the air out of my lungs, and my head rang with pain. Dazed and barely able to stand, I continued up the path, fighting the urge to lean against the canyon wall for support. I could hear nothing except the sound of my breathing. The audio equipment in my helmet had gone dead. I was panting. My legs were tight. I placed my hands on my thighs and pushed, hoping it would help me run.

Below me, the canyon was consumed with molten fire. Looking down the slope was like staring into Dante’s “Inferno.” The battleship had skidded across the canyon, cutting a deep gash and spewing fiery fuel and radioactive debris in every direction. The very earth around the ship seemed to combust in an explosion of flame, smoke, and steam. I did not see any people in my quick glimpse, but I saw the remains of an upturned tank as it melted in that blazing heat.

Even one mile from the crash site, the heat from the fires would have cooked me alive if it hadn’t been for my armor. For the only time in my career, I felt heat through my body glove. As I reached the top of the trail, Lee and another man grabbed my arms. My legs locked and I started to fall, but they held me up. I could tell that they were trying to speak to me, but I heard nothing through my dead audio equipment.

Lee and the private lowered me to the ground. I fell on my back and stared into the sky. Above me, a U.A. Phantom fighter circled in triumph. An entire regiment had been demolished; but for Robert Thurston, Little Man was a triumph indeed.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Growing up in an orphanage, I sometimes imagined that I had parents on another planet looking for me. In my fantasies, my parents kept a room on the off chance that I would someday return. The room would have a crib, a bicycle, and closets filled with toys. Until they found me, my parents would seal that room, entombing its contents. In my mind’s eye, I saw the room as dark and filled with shadows. Dust covered the toys and crib.

Over the years, my childhood dreams were replaced by adult realities, and I forgot about that room until I returned to the Kamehameha with only six of my men. When I entered our vacated barracks, I experienced the very emotions that my imaginary parents would have felt whenever they visited my imaginary room.

Of the twenty-three hundred men sent down to Little Man, only seven survived. There were no wounded. That was the reality, and I kept on realizing it again and again. Lee and I did not speak much when we returned from Little Man. We were not mad at each other, we simply had nothing to say. We returned to our living quarters with five privates in tow and the rows of empty bunks looked like a cemetery. You can shake a jar filled with marbles and never hear a sound. Take all but a few of those marbles out, and those last few will rattle around in the empty space. We rattled around corridors once teeming with Marines. We were the ghosts. Captain Olivera allowed us to remain in our barracks, but he closed down the mess hall, the bar, and the sick bay. That meant we ate with the ship’s crew, which might have been the most haunting part of having survived.

The first time we went to the upper decks for a meal was like stepping onto an alien planet. When the elevator doors opened, we saw sailors walking in every direction. Men talking, some shouting, others rushing past the door—I had forgotten what it felt like to be among the living. I stepped off the lift. Lee followed. The hall fell silent. People slowed down and watched us. Nobody told us to leave. People simply stepped out of our way as we walked to the mess hall. We arrived during the middle of the early dinner rush. Looking through the window, I saw men with trays walking around in search of places to sit. I heard the loud din of hundreds of conversations and remembered when our mess hall was equally loud. The noise evaporated as we entered the doorway. We were the only men wearing Marines’ uniforms. Everyone knew who we were. I heard whispers and felt people staring, but nobody approached us.

I reached for a tray, and somebody handed it to me. “Thank you,” I said. The man did not respond.

The battle on Little Man lit a fire in the public’s imagination. “The New Little Big Horn” said the Unified Authority Broadcasting Company (UABC) headlines. Other famous massacres were also invoked. One reporter called it “a modern-day Pearl Harbor,” an irony that would not have been lost on Yoshi Yamashiro, though I doubt the reporter recognized it.

The Pentagon served up an endless supply of details about the battle, milking it for every drop of public support. A briefing officer held a meeting in which he traced our movements using maps. The public affairs office released photographs of the captured map room. The Joint Chiefs gave the UABC profiles and photographs of the hundred officers who died during the assault. Captain Gaylan McKay, a promising officer in life, became a public figure in death.

The Pentagon did not release information about survivors, but somehow the press got wind of us. We were dubbed, “The Little Man 7.” Probably hoping that the story would go away, the Joint Chiefs acknowledged only that “A fast-thinking sergeant had managed to evacuate six men from the field.”

They did not release my name. I did not care.

Over the next six weeks, as the Pentagon released a litany of tidbits about the Little Man 7, SC

Command ignored us as we rattled around the bowels of the Kamehameha . Once word was out about the survivors, I think the Joint Chiefs hoped that the public’s interest in Little Man would cool, but it continued to grow.

As time went by, Lee returned to his weight training, and I became obsessed with marksmanship. I practiced with automatic rifles, grenade launchers, and sniper rifles, shooting round after round. Lee and I went to the crewmen’s bar almost every night. The sailors seemed used to us by that time. Some invited us to sit with them whenever we showed up. By the time our transfers came, Lee and I had almost forgotten about the animosity between sailors and Marines.

Having spent a month and a half hoping for the public to forget about the Little Man 7, Washington finally embraced us. In his capacity as the secretary of the Navy, Admiral Huang announced plans to bootstrap us to officer status. The thought of promoting a Liberator must have caused him great pain. Lee and the other men were transferred to Officer Training School in Australia. I was called to appear before the House of Representatives in Washington, DC.

The night before Lee and the others left for OTS, we all went to the crewmen’s bar for one last gathering. We found that news of our transfers had spread throughout the ship. As we entered the bar, some sailors called to us to join them.

“Officers,” one of the men said, clapping Lee on the back. “If someone would have told me that I all I had to do was survive a massacre and a crash to become an officer, I’d have done it five years ago.”

Everybody laughed, including me. I didn’t think he was funny, but more than a month had passed. In military terms, my grieving period was over.

“Lee and the others are shipping out tomorrow,” I said.

“Congratulations.” The sailors looked delighted. One of them reached over and shook Lee’s hand. “I’d better do this now,” he joked. “Next time I may have to salute you pricks.”

“When are you leaving, Harris?” another sailor asked.

“Not for a couple of days,” I said.

“I can’t believe they’re shipping all of you out,” the sailor responded.

“What did you expect to happen to them?” another sailor asked. “Olivera needs to make room, doesn’t he?”

“Make room for what?” I asked.

“SEALs,” the sailor said, then he took a long pull of his brew. “Squads of them . . . hundreds of them.”

Lee and I looked at each other. That was the first we had heard about SEALs. Until we received our transfers, we’d both expected to remain on the Kamehameha to train new Marines.

“That’s the scuttlebutt,” another sailor said. “I’m surprised you never heard it.”

“Did you know that Harris is going to Washington?” Lee asked.

“We heard all about the medal,” a sailor said. “Everybody knows it. You’re the pride of the ship.”

“A medal?” I asked.

“You know more about it than we do,” Lee said.

“Harris,” the man said, putting down his drink and staring me right in the eye, “why else would you appear before Congress?”

Lee’s shuttle left at 0900 the next morning. I went down to the hangar and saw him and the other survivors off. On my way back to the barracks, I paused beside the storage closet that had once served as an office for Captain Gaylan McKay. Moving on, I passed the mess hall, which sat dark and empty. Not much farther along, I saw the sea-soldier bar. As I neared the barracks, I heard people talking up ahead.

“They mostly use light arms,” one of the men said, “automatic rifles, grenades, explosives. That’s about it. We can probably reduce the floor space in the shooting range.”

“They’re not going to blow shit up on board ship, are they?”

“I don’t know. They have to practice somewhere.”

Four engineers stood in the open door of the training ground. They paused to look at me as I turned the corner. I had seen one of them in the crewmen’s bar on several occasions. He smiled. “Sergeant Harris, I thought you were flying to Washington, DC.”

“I leave in two days,” I said. “You’re reconfiguring the training area?”

“Getting it ready for the SEALs. Huang ordered the entire deck redesigned. It will take months to finish everything.” The engineer I knew stepped away from the others and lowered his tone before speaking again. “I’ve never seen SEALs before, but I hear they’re practically midgets. That’s the rumor.”

As a guest of the House of Representatives, I expected to travel in style. When I reached the hangar, I found the standard-issue military transport—huge, noisy, and built to carry sixty highly uncomfortable passengers. The Kamehameha was still orbiting Little Man; we were nine miserable days from the nearest broadcast discs.

Feeling dejected, I trudged up the ramp to the transport. I remembered that Admiral Klyber had modified the cabin of one of the ships to look like a living room with couches and a bar. All I found on my flight were sixty high-backed chairs. After stowing my bags in a locker, I settled into the seat that would be my home for the next nine days. As I waited for takeoff, someone slid into the seat next to mine.

“Sergeant Harris, I presume,” a man with a high and officious voice said.

“I am,” I said, without turning to look. I knew that a voice like that could only belong to a bureaucrat, the kind of person who would turn the coming trip from misery to torture.

“I am Nester Smart, Sergeant,” the man said in his high-pitched snappy voice. “I have been assigned to accompany you to Washington.”

“All the way to Washington?” I asked.

“They’re not going to jettison me in space, Harris,” he said.

Nester Smart? Nester Smart? I had heard that name before. I turned and recognized the face. “Aren’t you the governor of Ezer Kri?”

“I was the interim governor,” he said. “A new governor has been elected. I was just there as a troubleshooter.”

“I see,” I said, thinking to myself that I knew a little something about shooting trouble.

“We have ten days, Sergeant,” Smart said. “It isn’t nearly enough time, but we will have to make do. You’ve got a lot to learn before we can present you to the House.”

Hearing Smart, I felt exhaustion sweep across my brain. He planned to snipe and lecture me the entire trip, spitting information at me as if giving orders.

The shuttle lifted off the launchpad. Watching the Kamehameha shrink into space, I knew Smart was right. I was an enlisted Marine. What did I know about politics? I took a long look at the various ships flying between the Kamehameha and Little Man, then sat back and turned to Smart. Now that I had become resigned to him, I took a real look at the man and realized that he was several inches taller than I. An athletic-looking man with squared shoulders and a rugged jaw, he looked more like a soldier than a pencil pusher.

“Now that I have your attention, perhaps we can discuss your visit to the capital,” he said, a smirk on his lips. “You may not be aware of it, but several congressmen protested our actions on Little Man. There’s been a lot of infighting between the House and the Senate lately.”

“Do you mean things like Congress passing a bill to cut military spending?”

“You’ve heard about that?”

“And the Senate calling for more orphanages?”

“Bravo,” Smart said, clapping his hands in nearly silent applause. “A soldier who reads the news. What will they come up with next?”

“I’m a Marine,” I said.

“Yes, I know that,” said Smart.

“I’m not a soldier. Do you call Navy personnel soldiers?”

“They’re sailors,” said Smart.

“And I am a Marine.”

Smart smiled, but his eyes narrowed, and he looked me over carefully. “A Marine who follows the news,” he said, the muscles in his jaw visibly clenched.

“Yes, well, unfortunately, we Marines can’t spend our entire lives shooting people and breaking things.” I looked back out the window and saw nothing but stars.

“You’ll find that I do not have much of a sense of humor, Sergeant. I don’t make jokes during the best of times, and this is not my idea of the best of times. To be honest with you, I don’t approve of Marines speaking on Capitol Hill.”

“Whose idea was it?” I asked.

“You’re considered a hero, Sergeant Harris. Everybody loves a hero, especially in politics, but not everybody loves you. There are congressmen who will try to twist your testimony to further their own political agendas.”

“The congressman from Ezer Kri?” I asked.

“James Smith? He’s the least of your worries. The last representative from Ezer Kri disappeared with Yamashiro. Smith is an appointee,” Smart said. “If you run into trouble, it’s going to come from somebody like Gordon Hughes.”

“From Olympus Kri?” I asked.

“Very good,” Smart said. “The representative from Olympus Kri. He will not take you head-on. You’re one of the Little Man 7. Picking a fight with you would not be politic. He might try to make the invasion look like the first hostile action in an undeclared war. The question is how he can make Little Man look illegal without openly attacking you.”

So I’m still a pawn? I said to myself. A hero who would shortly be among the first clones ever made an officer, and I was still a pawn . . . story of my life. I felt trapped. “Will you be there when I go before the House?”

“Harris, I’m not letting you out of my sight until you leave Washington. That is a promise.”

Suddenly traveling with Smart did not seem so bad.

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

“Do you know your way around Washington, DC?” Nester Smart asked. The way I pressed my face against the window to see every last detail should have answered his question. The capital of the Unified Authority lay spread under a clear afternoon sky. With its rows of gleaming white marble buildings, the city simply looked perfect. This was the city I saw in the news and read about in books. “I’ve never been here before.”

Our transport began its approach, flying low over a row of skyscrapers. I saw people standing on balconies.

Off in the distance, I saw the Capitol, an immense marble building with a three-hundred-foot dome of white marble. Two miles wide and nearly three miles deep, the Capitol was the largest building on the face of the Earth. It rose twenty stories into the air, and I had no idea how deep its basements ran.

“The Capitol,” I said.

“Good, Harris. You know your landmarks,” Smart said, with a smirk.

The architect who designed the Capitol had had an eye for symbolism. If you stretched its corridors into one long line, that line would have been twenty-four thousand miles long, the circumference of the Earth. The building had 192 entrances—one for each of the Earth nations that became part of the Unified Authority. The building had 768 elevators, one for every signer of the original U.A. constitution. There were dozens of subtle touches like that. When I was growing up, every schoolboy learned the Capitol’s numerology.

I also saw the White House, a historic museum that once housed the presidents of the United States. The scholars who framed the Unified Authority replaced the executive branch with the Linear Committee. If the rumors were true, the Linear Committee sometimes conducted business in an oval-shaped office inside the White House.

A highly manicured mall with gleaming walkways and marble fountains stretched between the White House and the Capitol. Thousands of people—tourists, bureaucrats, and politicians—walked that mall. From our transport, they looked like dust mites swirling in a shaft of light.

“I can barely wait to get out and explore the city,” I said, both anxious to see the capital of the known universe and to get away from Nester Smart.

“You are going to spend a quiet evening locked away in Navy housing,” Smart said. “We cannot afford for you to show up tomorrow with a hangover.”

Our transport began its vertical descent to a landing pad. Smart slipped out of his chair and pulled his jacket off a hanger. He smoothed it with a sharp tug on the lapels. Reaching for the inside breast pocket of the coat, he pulled a business card out and wrote a note on the back of it. After giving it a quick read, he handed it to me.

“There is a driver waiting outside. He will take you to the Navy base. Show this card to the guard at the gate. Also, your promotion is now official. Befitting your war-hero status, you are now a lieutenant in the Unified Authority Marines.

“You will find your new wardrobe in the apartment. I suppose congratulations are in order, Lieutenant Harris.”

The White House had guest rooms, but I was not invited to stay in those hallowed halls. Those rooms were reserved for visiting politicians and power brokers, the kinds of people who made their living by sending clones to war. Spending the night in the barracks suited me fine. The guards outside the Navy base were not clones. The one who inspected my identification had blond hair and green eyes. He looked over my ID, then read Smart’s note. “You’re one of the Little Man 7, right?” he asked. “I hear that you’re speaking in the House of Representatives tomorrow. Congress doesn’t usually send visitors out here.”

“Yeah, lucky me.”

“Officers’ country is straight ahead,” the guard said. “You can’t miss it.

“Captain Baxter, our base commander, left a message for you. He wants to meet with you. You’ll want to shower and change your uniform before presenting yourself. Baxter’s a stickler on uniforms.”

My driver dropped me at the barracks door. Carrying my rucksack over my shoulder, I found my room. The lock was programmed to recognize my ID card. I swiped my card through a slot, and the door slid open. It was the first time I had ever stayed in a room with a locking door. I considered that for a moment.

I had spent my life sharing barracks with dozens of other men. I heard them snore, and they heard me. We dressed in front of each other, showered together, stowed our belongings in lockers. With the exception of my two weeks of leave in Hawaii, the “squad bay” life was the only life I knew. Now I stepped into a room with a single bed. The room had a closet, a dresser, and a bathroom. Smiling and feeling slightly ashamed, I placed my ruck down, walked around the room turning on a lamp here, dragging my finger across the desk there, and allowing water to run from a faucet. I took a shower and shaved. Nine days of travel had left my blouse badly wrinkled; but it was an enlisted man’s blouse. In the closet, I found a uniform with the small gold bar of a second lieutenant on the shoulder. I dressed as an officer and left to meet the base commander.

“May I help you?” a civilian secretary asked.

I told her that I was a guest.

“Lieutenant Harris, of course,” she said. “Please wait here.” Watching me as she stepped away from her desk, she almost tripped over one of the legs of her chair. She turned and sped into a small doorway, emerging a moment later with several officers. That kind of reception would have made me nervous except that the officers seemed so happy to meet me.

“Lieutenant Harris?” a captain in dress whites asked.

“Sir,” I said, saluting.

The entire company broke into huge, toothy smiles. “A pleasure to meet you, Lieutenant,” the captain said, saluting first, then reaching across the counter and shaking my hand. “I’m Geoffrey Baxter.” The other officers also reached across and shook my hand.

“Do you have a moment? Are you meeting with anyone this evening?”

“No,” I said.

“What?” gasped another captain. “No reception? They’re not putting you up in a stateroom?

Outrageous! These politicians treat the military like dogs.”

Baxter led me into a large office, and we sat in a row of chairs. As the receptionist brought us drinks, the officers crowded around me, and more officers strayed into the room. “I’m not sure that I understand. Were you expecting me?”

“Expecting you? We’ve been waiting for you,” Baxter said. “Harris, you’re famous around here.” He looked to the other officers, who all nodded in agreement. “Your photograph is all over the mediaLink.”

“My photograph?” I asked. “How about my men?”

“They’re clones, aren’t they? Everybody knows what they look like,” an officer with a thick red mustache commented.

“Have you had dinner yet?” Baxter asked.

“I was going to ask for directions to the officers’ mess,” I said.

“No mess hall food for you. Not tonight,” another officer said. “Not for you.”

“I know you’ve just arrived, but are you up to a night out?” Baxter asked. I smiled.

“I know a good sports bar,” the officer with the mustache said. The idea of a place with loads of booze and marginal food appealed to all of us.

Fourteen of us piled into three cars and headed toward the heart of DC. The Capitol, an imposing sight during the day, was even more impressive at night. Bright lights illuminated its massive white walls, casting long and dramatic shadows onto its towering dome. Just behind the Capitol, the white cube of the Pentagon glowed. The Pentagon, which had been rebuilt into a perfect cube, retained its traditional name in a nod to history. Seeing the buildings from the freeway, I could not appreciate their grand size.

So many buildings and streetlights burned through the night that the sky over Washington, DC, glimmered a pale blue-white. The glow of the city could be seen from miles away. I could not see stars when I looked up, but I saw radiant neon in every direction, spinning signs, video-display billboards, bars and restaurants with facades so bright that I could shut my eyes and see the luminance through closed eyelids. I had never imagined such a place. Dance clubs, restaurants, bars, casinos, sports dens, theaters—the attractions never endled.

And the city itself seemed alive. The sidewalks were filled. Late-night crowds bustled across breezeways between buildings. We arrived at the sports bar at 1930 hours and found it so crowded that we could not get seated before 2030, did not start dinner until nearly 2130, and chased down dinner with several rounds of drinks.

The officers I was with held up at the bar better than the clones from my late platoon. Most clones got drunk on beer and avoided harder liquor, but Baxter and his band of natural-borns kept downing shots long after their speech slurred. One major drank until his legs became numb. We had to carry him to his car.

We did not get home until long after midnight. I did not get to bed until well after 0200. I’m not making excuses, but I am explaining why I did not arrive at the House of Representatives in satisfactory condition. Sleep-addled and mildly buzzed from a long night of drinking, I found myself leaning against the wall of the elevator for support as I rode up to meet Nester Smart. The doors slid open, and the angry former interim governor of Ezer Kri snarled, “What the hell happened to you?” Dressed for bureaucratic battle, Smart wore a dark blue suit and a bright red necktie. With his massive shoulders and square frame, Smart looked elegant. But there was nothing elegant about the twisted expression on his face.

“I’m just a little tired,” I said. “I had a late night out with some officers from the base.”

“Imbecile,” he said, with chilling enunciation. “You are supposed to appear before the House in two hours, and you look like you just fell out of bed.”

“You mind keeping your voice down?” I asked as I stepped off the lift. Rubbing my forehead, I reminded myself that I was in Smart’s arena. He knew the traps and the pitfalls here. Smart led me down “Liberty Boulevard,” a wide hallway with royal blue carpeting and a mural of seventeenth-century battle scenes painted onto a rounded ceiling. Shafts of sunlight lanced down from those windows. The air was cool, but the sunlight pouring in through the windows was warm.

“This is an amazing city,” I said. “It must be old hat for you.”

“You never get used to it, Harris,” Smart said. “That’s the intoxicating thing about life in Washington, you never get used to it.”

As we turned off to a less spectacular corridor, Smart pointed to a two-paneled door. “Do you know what that is?” Smart asked.

I shook my head.

“That, Harris, is the lion’s den. That is the chamber. Behind those doors are one thousand twenty-six congressmen. Some of them want to make you a hero. Some of them will use you to attack the military. None of them, Lieutenant, are your friends. The first rule of survival in Washington, DC, is that you have no friends. You may have allies, but you do not have friends.”

“That’s bleak,” I said. “I think I prefer military combat.”

“This is the only battlefield that matters, Lieutenant,” Smart said. “Nothing you do out there matters. Everything permanent is done in this building.”

Death is pretty permanent, I thought. I walked over to a window and peered out over the mall. It was raining outside. Twenty floors below me, I saw people with umbrellas and raincoats walking quickly to get out of the rain. Preparing to appear before the House, I felt the same pleasant rush of endorphins and adrenaline that coursed through my veins during combat. I had some idea of what to expect. Smart spent the flight from Scutum-Crux telling me horror stories, and I had every reason to believe the pompous bastard.

“Remember, Harris, these people are looking for ammunition. Answer questions as briefly as possible. You have no friends in the House of Representatives. If a congressman is friendly, it’s only because he wants to look good for the voters back home.”

The door to the chamber opened and three pages came to meet us. They were mere kids—college age .

. . my age and possibly a few years older, but raised rich and inexperienced. They had never seen death and probably never would.

“Governor Smart,” one of the pages said. “Did you accomplish what you wanted on Ezer Kri?” Taken on face value, that seemed like a warm greeting. The words sounded interested, and the boy asking them looked friendly, but Smart must have noticed a barb in his voice. Smart nodded curtly but did not speak.

“And you must be Lieutenant Harris,” the page said as he turned toward me. He reached to shake my hand but only took my fingers in the limpest of grips. “Good of you to come, Lieutenant. Why don’t you gentlemen follow me?” He turned to lead us into the House.

“Tommy Guileman,” Smart whispered into my ear. “He’s Gordon Hughes’s top aide.”

If Smart and I had been allowed to wear combat helmets in the House of Representatives, we could have communicated over the interLink. Smart could have told me all about Guileman. He could have identified every member of the House as an ally or an enemy. Since we did not have the benefit of helmets on the floor, I needed to watch Nester Smart and study his expressions for clues. The House of Representative chambers looked something like a church. The floor was divided into two wide sections. As the pages led us down the center aisle, several representatives patted me on the back or reached out to shake my hand.

At the far end of the floor I saw a dais. On it were two desks, one for Gordon Hughes, Speaker of the House, and one for Arnold Lund, the leader of the Loyal Opposition. I took my place at a pulpit between them and thought of Jesus Christ being crucified between two thieves. Below me, the House spread out in a vast sea of desks, politicians, and bureaucrats. Fortunately, I was not alone. Nester Smart hovered right beside me.

I had seen the chamber in hundreds of mediaLink stories, but that did not prepare me for the experience of entering it. A bundle of thirty microphones poked toward my face from the top of the podium. One clump had been bound together like a bouquet of flowers. Across the floor, three rows of mediaLink cameras lined the far wall. They reminded me of rifles in a firing squad. Later that day, I would find out that I had been speaking in a closed session. The cameras sat idle, and most of the microphones were not hot.

My wild ride was about to begin. “Members of the House of Representatives, it is my pleasure to present Lieutenant Wayson Harris of the Unified Authority Marine Corps. As you know, Lieutenant Harris is a survivor of the battle at Little Man.”

With that, the members of the House rose to their feet and applauded. It was a heady moment, both intimidating and thrilling.

“Do you have prepared remarks?” the Speaker asked.

“No, sir,” I said.

“Quite understandable,” the Speaker said in a jaunty voice. “Perhaps we should open this session to the floor. I am sure many members have questions for you.”

Hearing that, I felt my stomach sink.

“If there are no objections, I would like to open with a few questions,” the leader of the Loyal Opposition said.

“The chair recognizes Representative Arnold Lund,” Hughes said. Smart smiled. Apparently the meeting had started in friendly territory.

Above me, the minority leader sat on an elevated portion of the dais behind a wooden wall. I had to look almost straight up to see his face.

“Lieutenant, members of the House, as you know, the Republic has entered dark times in which separatist factions have challenged our government.”

Nester Smart moved toward me and leaned close enough to whisper in my ear. “He’s on our side,”

Smart whispered. “He is signaling us and his allies how to play this. He will try to shield you if the questions get hostile.”

“As we all know,” Lund continued, “a landing force was sent to Little Man for peaceful purposes. More than two thousand Marines were brutally butchered . . .”

“I am certain that history will show that these men died bravely . . .” The leader of the Loyal Opposition showed no signs of slowing as his speech passed the seven-minute mark.

“Were it possible, we should erect a statue for every victim of that holocaust.” Lund waxed on and on about the innocence of our twenty-three hundred-man, highly armed landing party and the brutality of the Mogat response. He talked about the unprovoked attack on the Kamehameha and the good fortune that other ships happened to be nearby.

“Goddamn windbag” Smart whispered angrily.

“Lieutenant Wayson Harris is one of only seven men who survived that unprovoked attack,” the congressman went on. “Fellow representatives, I would personally like to thank Lieutenant Harris for his valor.”

Loud applause rang throughout the chamber, echoing fiercely around us. The shooting match was about to begin. Behind me, Hughes banged his gavel and called for order. “The floor now recognizes the junior representative from Olympus Kri.”

An old woman with crinkled salt-and-pepper hair pulled back in a tight bun stood. She pushed her wire-frame spectacles up the bridge of her nose and spoke in overtly sweet tones. “Olympus Kri celebrates your safe return from Little Man, Lieutenant Harris. I am sure the battle must have been a very grueling experience. What can you tell us about the nature of the incursion on Little Man?”

“The nature?” I asked.

“What was the reason you went down to Little Man?” the congresswoman asked. She leaned forward on her desk to take weight off her feet.

“Remember, you are an ignorant foot soldier,” Smart whispered in my ear.

“Why did I go to Little Man, ma’am?” I repeated. “We went because that was where the transport dropped us off.”

The soft hum of laughter echoed through the chamber.

The congresswoman managed a weak response. “I see. Well, Lieutenant, as I understand it, there were twenty-three hundred Marines on Little Man. That sounds like quite an invasion.”

With that she stopped speaking. Perhaps she expected me to respond, but I had nothing to say. She hadn’t asked me a question. An awkward silence swelled.

“Is it?” the congresswoman finally asked.

“Excuse me?” I asked. I looked over at Smart and saw an approving smile.

“Why did you invade Little Man?” she asked.

“I was not involved in the planning of this mission, ma’am.”

“Twenty-three hundred units?” she persisted. “What reason were you given for sending so many men to the planet?”

“Ma’am, I was a sergeant. Nobody gives sergeants reasons. They just tell us what to do.”

“I see,” she said.

Nester Smart leaned over to whisper something to me, but the congresswoman stopped him. “Did you have something to add, Mr. Smart?” she asked.

“I was just advising Lieutenant Harris about the kind of information you might be looking for,” Smart said.

“From your vast store of battlefield experience, Mr. Smart?” the congresswoman quipped. There was a burst of laughter on the floor. Smart turned red but said nothing.

“Lieutenant, I am merely trying to determine why so many Marines were sent to the surface of Little Man. I am not asking for an official explanation. You are a soldier in the Unified Authority Marine Corps. Surely you have some understanding about how things are done.”

“It’s not unusual for ships to send their complement of Marines to a planet, ma’am,” I said.

“Two thousand men?” she questioned. “That sounds more like an occupying force.”

“Ma’am, twenty-three hundred men with light arms is a tiny force. We keep more men than that on most friendly planets.”

“I see,” said the congresswoman. “Lieutenant Harris, I thank you for your service to the Republic.” With that, she returned to her desk.

I recognized the next senator’s face from countless mediaLink stories. Tall, with dark skin and a beard that looked like a chocolate smudge around his mouth, this was Congressman Bill Hawkins who represented a group of small planets in the Sagittarius Arm. Except for the telltale white streaks that tinged his hair, Hawkins looked like an athletic thirty-year-old. I’d read somewhere that he was actually in his fifties.

“Lieutenant Harris, I salute you for your service to our fine Republic,” he said. He spoke slowly and in a clear, strong voice. Earth-born and raised, Hawkins had been a fighter pilot—his was the voice of one veteran speaking to another. He placed a foot on his seat and leaned forward. As he went on, however, his demeanor transformed into that of a politician.

“Lieutenant, perhaps I can assist my esteemed colleague from Olympus Kri,” he began. Around the chamber, many representatives began muttering protests.

“Perhaps my esteemed colleague has not noticed that the lieutenant has already answered her questions,”

said Opposition Leader Lund.

“Certain questions remained unanswered,” Hawkins said, turning his attention on Lund.

“This is supposed to be a presentation, not a board of inquiry,” a congressman shouted from the floor.

“Order. Order!” Hughes said, banging his gavel. “Representative Hawkins has the floor.”

“And I do congratulate the lieutenant,” Hawkins said, looking over my head toward Representative Gordon Hughes. “Well done, Lieutenant Harris. But, in light of new information, certain questions must be answered.”

“What information is that?” Nester Smart broke in.

“Oh yes, Nester Smart, good of you to escort the lieutenant,” Hawkins said with a smirk. “After surviving a brutal battle on Little Man, it would be a shame if this fine Marine was lost in a dangerous place like the House of Representatives.”

Laughter and angry shouts erupted around the chamber.

“Order,” Congressman Hughes called. His booming voice stung my ears. “What new information have you acquired, Senator Hawkins?”

Hawkins reached down and pulled a combat helmet out from beneath his desk. “Do you recognize this, Lieutenant?” he asked.

“That is a combat helmet,” I said.

“Your combat helmet, Lieutenant. One of my aides retrieved it from a repair shop on the Kamehameha . It appears that its audio sensors failed during the battle.” Hawkins held the helmet so that everyone on the floor could see it. “We downloaded the data recorded in the memory chip of this helmet. The data shows that you acted most heroically, Lieutenant Harris.”

“Thank you, Senator,” I answered quietly. I knew something bad was coming, but I had no idea what it might be. My mind started racing through the entire mission. Would Hawkins accuse me of cowardice for abandoning Captain McKay? Would he call me a traitor for leading my men out of the canyon?

“Your mission, however, was about more than squatters,” Hawkins said. “Congressman Hughes, with your permission I would like to show the chamber some excerpts from Lieutenant Harris’s record.”

“This is unacceptable!” blared the minority leader. “Mr. Speaker, this is a blind-side attack.”

Hawkins’s aides jumped to their feet and shouted in protest.

“Ironic,” Hawkins said, putting up an open hand to silence his delegation. “That is the exact accusation I have against the men who planned the invasion of Little Man. We can view this record in a special committee if that is what my esteemed colleague wishes, but a committee investigation would require the testimony of all of the men who survived this attack. We would need them to verify that the records have not been altered.

“Today, we have the benefit of Lieutenant Harris’s expertise. I think we should view his record while he is here and able to comment on it. If you like, Mr. Speaker, we can put it up to a vote.”

Looking around the chamber, I could see that the majority of the people in attendance wanted to know what Hawkins had up his sleeve. Though I could not make out specific conversations, the tenor of the talk around the chamber seemed excited.

Hughes seemed to sense the excitement. “There is no need to hold a vote,” he said. “I will allow you to show your information.”

A large screen dropped from the ceiling behind the dais. By the faint glow that filled the chamber, I could tell that smaller monitors lit up on the representatives’ desks.

“Do you recognize this scene, Lieutenant?” Hawkins asked.

“Yes,” I said. I turned to Nester Smart for help, but he looked completely dumbstruck. “I was on guard duty the night before the battle.”

The ghost of First Sergeant Booth Lector came walking through the undergrowth.

“So the battle was the very next morning?” Hawkins asked.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

The video feed continued.

“What the hell did I ever do to you?” I asked from the screen.

“You were made, Harris. That’s reason enough. Just the fact that you exist was enough to get me transferred to this for-shit outfit,” said the ghost of Booth Lector. The video feed paused.

“Who is this man?” Hawkins asked.

“Master Sergeant Booth Lector,” I said.

“I know that, Lieutenant. I can read his identifier on the screen. I am asking about his relationship with you. What did he mean when he said that he was transferred because you exist?”

As I struggled to come up with a safe answer, Hawkins said, “Why don’t you think about that question as we watch more of this video feed?”

“I had nothing to do with it.”

“You had everything to do with it. You think this is a real mission? You think we are going to capture this entire planet with twenty-three hundred Marines? Is that what you think?

“They’d forgotten about us. Saul, Marshall, me . . . Nobody in Washington knew that there were any Liberators left. The brass knew about Shannon, but there was nothing anybody could do about him. Klyber kept him nearby, kept a watchful eye on him. Nobody could touch Shannon with Klyber guarding him. As far as everybody knew, Shannon was the last of us.

“Then you came along, Harris— a brand-new Liberator.

“You weren’t alone, you know. Klyber made five of you. We found the others. Marshall killed one in an orphanage. I killed three of them myself. But Klyber hid you . . . sent you to some godforsaken shit hill where no one would find you. By the time I did locate you, you were already on the Kamehameha.”

“I . . .”

“Shut up, Harris. You asked what’s bothering me, now I’m going to tell you. And you, you are going to shut your rat’s ass mouth and listen or I will shoot you. I will shoot you and say that the goddamn Japanese shot you.

“The government hated Liberators. Congress wanted us dead. As far as anyone knew, we were all dead. Then you showed up. I heard about that early promotion and wanted to fly out and cap you on that shit hill planet. I would have framed Crowley, but Klyber transferred you before I could get there.

“Next thing I know, you’re running missions for that asshole Huang. You stupid shit! Huang was the reason we were in hiding in the first place. As soon as I heard that you met Huang, I knew we were all dead. Once he got a whiff of a Liberator, he would go right back to the Pentagon and find every last one of us.

“And here we are, trying to take over a planet with twenty-three hundred Marines. This isn’t a mission, Harris, this is a cleansing. This is the last march of the Liberators, and if they need to kill off twenty-three hundred GI clones to finish us, it all works out fine on their balance sheets. They’re expendable.

“You want to know what I have against you, Harris? You are the death of the Liberators.”

“I was a young boy during the days of the Galactic Central War, Lieutenant. I toured the devastation of both New Prague and Dallas Prime shortly after graduating OTS. Lieutenant Harris, I have seen the destruction that Liberators do. Are you a Liberator?” Hawkins asked. I looked over at Nester Smart for advice. His eyes wide and scared, his face completely drained of blood, he took three steps back from me.

“Perhaps you have forgotten the mission of this body, Congressman.” The voice was cold, direct, and final. I recognized it at once, but turned to check. Admiral Bryce Klyber stood alone at the far end of the floor. He stood stiff and erect, his legs spread slightly wider than his shoulders and his hands clasped behind his back.

Turning to look at Klyber, Bill Hawkins fell silent. Everyone on the floor became silent. I could sense their fear.

“The mission of this body is to represent the people. When representatives take it upon themselves to exceed their mission, they endanger the institution itself,” Klyber said.

“And now, Congressman Hughes, if there are no more questions”—Klyber looked all around the floor, warning off anyone with the nerve to challenge him—“I suggest you propose a motion to recognize Lieutenant Harris’s gallant service and dismiss him.”

“I quite agree,” said Lund, the leader of the Loyal Opposition. With Admiral Klyber watching, Hughes took an open vote.

Across the floor, Bill Hawkins’s delegation exited the chamber. Ten minutes later, when Hughes tallied the vote, he noted that Hawkins abstained. The rest of the House, even the representatives from Olympus Kri, voted for my commendation.

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

I later found out that some of Nester Smart’s allies closed the session to the media. They did not know what Hughes and his camp had planned, but they did not trust the honorable congressman from Olympus Kri. Closing the session, however, did not prevent leaks.