CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

The ruins of Fort Washington blended in with the stores, churches, and houses in this ugly suburb. I found my way into a neighborhood that could only have been officer housing. The houses were three-bedroom jobs that all looked alike from the outside, right down to the flower beds and white picket fences. These homes had no more floor space than a two-bedroom apartment. They had patios the size of postage stamps and shingled roofs. Looking up the drive-ways, I saw upended tricycles and plastic swimming pools. I could almost hear the children playing.

Not wanting to approach the fort in daylight, I broke into one of these homes and hid inside it until nightfall. The front door of the house had been marked with a red JC, but the contents inside had not yet been picked over. I entered a clean kitchen that was orderly except for the pile of dirty dishes in the sink. Inside the pantry I found a jar of peanut butter that I ate by the spoonful as I waited for sunset. The officer who had lived in this home was a family man with a pretty platinum-blond wife and two little boys. I saw pictures of the family on the walls. The boys shared a single room sleeping on bunk beds with steel tube frames. Searching the house, I found a flashlight and a cheap pair of binoculars, both of which I took. I also found a book of fairy tales and a Bible, both of which I left behind. The wife had jars of fruit preserves in the garage. She and the boys had undoubtedly left the planet during the mass evacuation. Even if he was alive, her husband would never find them again. Not without the Broadcast Network.

Before leaving the house, I stowed my M27 and four grenades in the family linen closet under a stack of children’s blankets. I would need to travel light and kill quietly. I kept my particle beam pistol and the ridiculously large combat knife.

As the sun dropped on the horizon and the sky turned dark blue, I slipped back on to the street and traveled the last mile to Fort Washington. A tabby cat followed me from a distance as I walked down the street. The people had left their pets behind. The cats would roam free. Dogs left in houses would likely starve to death.

Fort Washington was a large compound encompassed by a chain link fence and razor wire. No lights burned anywhere that I could see, but I saw the glow of fires around the grounds. Lasers or looters had destroyed much of the fence. Making one last inventory check, I knelt beside the chassis of an overturned bus, examined my pistol to be sure it was charged, and stole on to the base. Since the attack on Earth, I had developed an inconvenient appreciation for human life. It was as if my neural programming had gone haywire. I had the same instincts as ever, but after seeing the Galactic Republic go up in flame, I now placed a value on humanity. I even had an idea about what was going wrong inside me. I was designed and programmed to protect the Unified Authority. My programming must have been specifically set up to do whatever was necessary for the protection of the Republic. Only now, there was no Republic. I had no trouble identifying the enemy, but the mental loop that let me justify any action had been closed.

The attack had left the base in ruins. Every building I passed was destroyed. The first building I saw was a barracks, an elongated brick dormitory for enlisted Marines. The building had caved in. More than anything else, Fort Washington reminded me of a college campus. It had old buildings and new ones, modern structures made out of the same red brick that the minutemen would have used had they built barracks during the Revolutionary War. Tradition. A network of tree-lined lanes laced the base together. Between the buildings were long, well-mowed stretches of grass that looked like city parks in miniature.

The base landscaping also included trees. There were thirty-foot firs and groups of leafed trees. As I walked around the base, I noticed large bundles hanging from the lower boughs of almost every tree. The bundles looked like rucksacks. They hung at the end of long leads of rope, dangling perfectly still, apparently so heavy that the low summer breeze did not move them.

Strange how the mind works. Coming into the base I did not notice these cocoons. Now that I saw a few, the mental veil dissolved from my eyes and I saw that they were everywhere, hanging from the trees, from the rafters of the buildings, and two or three bundles hung from each streetlamp. They were not rucksacks, of course. These were the Marines of Fort Washington. Pulling my flashlight from my pocket, I stole up to one of the streetlights. Three men dangled above me, two clones and an officer. The clones were clearly killed in combat. They had been stripped of their armor, but I could tell by the blistered skin of their faces and their charred bodysuits that they were killed by laser fire. Some grave robber must have found them while scavenging through the base. The officer, however, had not died during the raid. Someone had executed him, firing a single bullet into the side of his head from close range. I could see his tied hands through the bag. Shining my light on him, I saw that the top right corner of his head was a bloody, hollow mess. These were Callahan’s scarecrows. Killed in action or put to death after the battle, it didn’t matter. Jimmy Callahan strung up the bodies as a warning to other warlords that Fort Washington was his territory. If I looked around long enough, I might find Colonel Bernie Phillips hanging from a tree. As the base commander, Phillips had helped me stash Callahan. He was the one who helped me steal an Army jeep so that I could sneak into Fort Clinton. I was disgusted with myself for letting this desecration bother me.

There might have been 20,000 or even 30,000 men assigned to Fort Washington. Could Callahan and his men have strung up all of the bodies? Some of the Marines would have gone into town to fight. Seeing the hopelessness of the situation, some of the officers would have gone AWOL. The enlisted clones would have fought to the end.

I thought that many of the men killed during the attack would have been too torn up to hang, but that turned out to be wrong. Under a nearby tree, I saw a body without arms or legs or any of the familiar curves you associate with the human form. On closer inspection I discovered that it was nothing but a bunch of body parts. Somebody had stuffed this fellow into nylon netting used for laundry. Like I said before, most of the base lay in darkness. Crossing a hill, however, I heard the mechanical drone of a power generator. I had no trouble locating where the noise came from. Off in the distance, a two-story building shown in a bath of incandescent light. Glare from that building illuminated the broken buildings around it.

You could only describe Jimmy Callahan as a complete moron. Lying on the ground at the crest of a grassy hill, partially hidden by the six Corps corpses hanging above me, I could have picked off half of Callahan’s army with a single shot had I brought a rocket launcher. They had lined up in a tight group for some kind of parade.

The terrain he selected showed his lack of tactical training. He set up his headquarters in a building surrounded by hills. The hills formed a ring around him, giving me or any invading gang the high-ground advantage.

And then there was the light. Callahan felt compelled to show off to the world that he had a working power generator. The light from his headquarters illuminated his troops. I could see the men in the machine-gun nests set up on the veranda. I had a much better view of the sharpshooters on the roof than they had of me. Although they had night-for-day scopes, they would need to locate me before they could aim and shoot. I could see them clear as day.

A particle beam pistol, however, was not the right equipment for a sniper attack. It was a short-range weapon for killing people and blowing up targets within a thirty-feet radius. So I lay silently at the base of a tree, hidden from view by dangling corpses, and I watched. Most of Callahan’s men wore fatigues. Some carried M27s. Some carried pistols. I estimated Callahan’s troops at somewhere between 150 and 200 men. He had jeeps and all-terrain vehicles, and a few armored personnel carriers. How he had taken control of this territory with so few men I could not understand. Then I heard the rumble. An LG tank rumbled up the street toward the lighted building. The letters, LG , stood for low gravity . These units were made for use on planets with low gravity, obviously. Tell a Marine engineer to make a tank heavier and you can guess exactly what he’ll do. He adds thicker armor, heavier guns, more durable treads, and more powerful motors. Most tanks weighed about sixty-five tons or 130,000 pounds. The extra 70,000 pounds on an LG tank was dedicated to killing.

That was how Callahan became so powerful. Who or what could possibly stand up to that tank? All of the jets on Bolivar Air Base would surely have been destroyed, not that a jet could necessarily destroy a tank like this. Whoever took over Fort Clinton Army base might have similar tanks. I pulled out the binoculars and took a closer look at the situation. These were cheap “bird watcher”

quality gear, but they gave me a better view. I could read the markings on the tank as it rolled to within a few feet of that lighted building. I was just lowering the binoculars when an officer stepped out of the building. For an odd moment I thought it might be Colonel Phillips. I brought up the binoculars again. Jimmy Callahan, wearing one of Bernie Phillips’s colonel uniforms, strutted down the stairs like a made man who owns the future. His arms swinging at his sides and his head held high, he surveyed his troops. He barked orders and strutted around the tank pretending to inspect it. I did not even need these lousy peeps to see the self-satisfied expression on Callahan’s face.

“See any reason why I shouldn’t cap him?” The voice was so low it sounded like a whisper. Ray Freeman knelt beside me. He held a sniper’s rifle in one hand and a rocket launcher in the other. I pretended to have known he was there all along. “I don’t see the point in it,” I said.

“Looks like we’re going to be stuck on this planet for a long time, Harris,” Freeman said. “And I don’t want Callahan for president.”

He raised the rifle and sighted Callahan. It was a top grade rifle with a built-in silencer. No one more than twenty feet away would hear shots from that gun. Because of our elevated location, no one would spot us.

“So you’re bringing democracy to New Columbia,” I commented.

Freeman, who was about as likely to appreciate ironic humor as he was to learn ballet, merely grunted.

“What about the tank?” I asked.

“You worried about it?” he asked.

“Not especially,” I said. I wasn’t. I was more worried about the jeeps. In this gravity, the tank would rumble along so slowly that a five-year-old could outrun it.

“I didn’t think so.”

“But I’m not worried about Callahan, either,” I said, taking a quick glance at him through the binoculars. I was about to tell Freeman that I had a self-broadcasting ship.

“Me, either,” Freeman interrupted. And with that he pulled the trigger. Two hundred yards below us, a misty red halo formed around Callahan’s head, and he dropped to the ground. While the people below shouted in confusion and scattered, Freeman picked off the four sharpshooters on the top of the building. Let me rephrase that—he picked off the three snipers I had seen, plus the one that I had not noticed. Two of Callahan’s soldiers ran for a jeep. Freeman picked off the faster man before he reached the vehicle. He shot the second man as he tried to climb into the driver’s seat. Total chaos broke out below. The men in the machine-gun nests fired into the hills. Only one of the guns fired even near our direction. Freeman shot that gunner first, and then he took out the gunners in the other nests.

“You here to watch or help?” Freeman asked.

“You have things under control,” I said as I picked up the rocket launcher and aimed at the tank. Thinking this rocket would destroy that tank was the only miscalculation Freeman made. A shoulder-mounted rocket like this might damage that LG, but it sure as hell would not stop it.

“Do you know what to shoot?” Freeman asked.

“The tank?”

“Not the tank, the fuel depot.”

Located at the edge of the darkness was the fuel depot that the late Jimmy Callahan used to fill his vehicles. Somehow it had survived the Hinode Fleet’s attack. I aimed the rocket at a fuel tank and fired, triggering a grand explosion that lit up the night. The explosion was deafening. Hidden up on that hill, I heard it and felt the percussion. The force of the blast shook the ground and the sound thundered in my ears so that the vibrations became intermingled as one in my head. A fireball shot sixty feet into the air. It towered over smaller eruptions as underground tanks, pumps, and piping blew into shrapnel. Flames shot in all directions lighting the area with a golden glow. The rocket set off a chain reaction, igniting a network of underground fuel tanks that extended below the road. Fuel tank after fuel tank exploded leaving huge craters in the road. Made for use in a low gravity theater, that LG tank could not possibly come out after us.

Callahan’s troops were thugs, not soldiers. They would not regroup as quickly as Marines, but they would regroup. They would send scouts and assassins out to find us soon enough. We did not wait. Once he was sure that the tank and the jeeps could not follow, Freeman turned to leave. I watched men running around near the flames. The muffled bang of underground explosions, so different from the crackle of gunfire, echoed through the night air. The late Colonel Callahan’s men would not get their LG tank out of that cul de sac anytime soon. They might fill the craters if they became desperate or ambitious enough to mix tons and tons of concrete. That might work. They certainly did not have enough technical know-how to build a bridge over those pits.

Looking back behind me as I left the rise, I saw the tree under which I had hid. I saw the bodies dangling from its lowest boughs like strange black fruit against the orange hue of the fire.

“You didn’t have to kill Callahan,” I said as we crossed the fence and left the base.

“I wanted to,” Freeman said. He led me to a house on the same street as the house I had used.

“My Starliner is self-broadcasting,” I said, sounding even more annoyed than I felt. “We can leave anytime that we want.”

Freeman stiffened and looked back at me. “Self-broadcasting? We’re getting off this rock.”

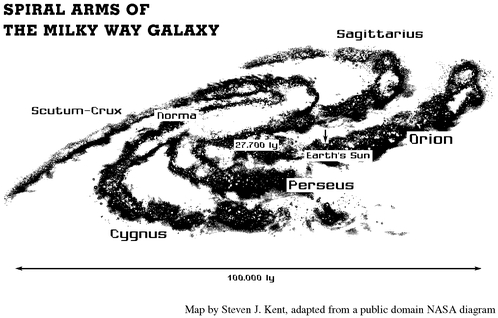

“It wouldn’t have mattered if Callahan was president of the friggin’ Orion Arm,” I said. “He wouldn’t have been able to touch us.”

Freeman thought about this for a moment then grinned. “So killing him was a bonus.”

Ray Freeman did not talk much. When he did speak, he seldom talked about himself. I gleaned some of what had happened from things he said over the next few days and constructed the rest of it in my mind. This is what I think happened when Freeman landed in Safe Harbor.

Freeman came in a few days before me. He arrived before the Hinode Fleet defeated the Earth Fleet and destroyed the Doctrinaire .

Freeman stole a van at the spaceport and drove until he reached that stretch of road that was too destroyed to pass. He left his van and hiked into town and found his way to the Marine base. Like me, Freeman did not believe that the Hinode Fleet could survive a battle with the Doctrinaire . I think he hoped to find Callahan and bring him to Earth for safekeeping.

When he got to Fort Washington, he found men wearing fatigues and armed with M27s gathering bodies. Here Freeman made a rare mistake. He assumed the men with the M27s were Marines. When he asked about their commanding officer, they took him to go see “the colonel.” Freeman did tell me that Callahan referred to himself as “the colonel.”

Alert as he was, Freeman would have noticed that Callahan’s thugs did not carry themselves like real Marines. He would have noticed the casual way they handled their firearms, the way they spoke to each other, and the slow pace at which they worked. Real enlisted men were clones. Unless all of Callahan’s men wore officers’ insignia, Freeman would have noticed that the men around him were not government-issue.

They took Freeman to the building Callahan used as his headquarters. That was a mistake. Freeman quietly surveyed the field, looking for strategic locations and tactical advantages. He had an eye for this. He would have spotted the tree at the top of the rise and known it was the perfect spot for an attack. By the time Callahan came out to speak, Ray Freeman knew how many snipers Callahan had on the roof and where they were positioned. He knew how many machine-gun nests were along the veranda. He would have seen the LG tank rumbling around the parade grounds, and he would have taken note of the fuel depot as well.

Callahan decided to have Freeman killed. He must have decided that since he and his thugs had the guns, they would have no trouble executing the gigantic black man. They probably took him to the same field where they did their officer executions. The moment Freeman decided the odds were right, he killed his would-be executioners.

Freeman never left an attack unavenged. He hiked to Fort Clinton the following day. Knowing that the Army base would be under gang control as well, he presented himself with a winning offer. In exchange for a sniper rifle, a rocket launcher, and a ride back to Callahan territory, Freeman offered to cripple the gang holding Fort Washington. How could the gangsters at Fort Clinton refuse? They gave him a stealth jeep and the best sniper rifle they could find.

That night, as he returned to even the score with Callahan, he found me.

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

Freeman had a stealth jeep, but he did not want to use it. The gangs whose territories bordered the Marine base would have heard the shooting. Anybody within thirty miles would have heard the fuel depot explode. Our attack would have touched off a feeding frenzy in Safe Harbor.

“How long did it take you to get in from the spaceport?” Freeman asked.

“Two days,” I said. “One day to reach town and one day to cross town.”

“Two days,” Freeman repeated.

“We could cross town in less than an hour in that jeep,” I said. “We’d be at the spaceport by sunup.”

Freeman shook his head. The house was dark inside. We were in a basement with only subterranean windows. We could see up and down the street from our ankle-high perspective. The street was dark and still, but we expected marauders to follow soon. Callahan’s troops would come looking for us. So would his enemies.

“How did you come through town?” Freeman asked.

“On foot,” I said.

“Did you cross main roads?”

“Alleys, mostly,” I said. “I hiked through a couple of department stores to avoid being seen.”

“The main roads are broken up,” Freeman said. “We’d end up driving through the neighborhoods.”

“We would be sitting ducks,” I said. “There are gangs everywhere. All it would take is some hotshot with a roadblock and a bazooka.”

Freeman watched me figure this out. Too silent by nature to help me catch up, he was often one step ahead of me. There was a flicker of movement on the street. He rose to his feet and moved toward the window, his massive body forming a black silhouette in the thin light. Up the street, five men moved slowly toward us. Four of them formed an uneven picket line, with the fifth covering their back. These were, as I said before, thugs, not soldiers. They walked right up the middle of the street apparently giving no thought to cover. They had torches attached to the barrels of their rifles, and they swept the ground before them with the beams of those torches. They made splendid targets.

“Think those are the scouts or the hunting party?” I asked.

“What difference does it make?” Freeman asked as he raised that sniper rifle and pointed it out the window.

“They’ll be looking for us,” I said. “However many men Callahan had in his gang with whatever weapons they have left, they will be looking for us.”

Freeman nodded. In the waning light, I could just make out the features of his face. “Smashing a crippled gang is easier than smashing a whole one.”

“So do we stay here tonight?” I asked. I could not help wondering when the killing would end. We could simply hide in the basement and pick off gang members as they approached. Freeman could hold down the fort, but one of us, meaning me, would need to check the street. I pointed this out, then ran up the stairs and slipped out of the house.

It was a silent, balmy night with the first hints of a cooling breeze. The snap and crackle of the fire on the base carried in the air, but it was far away and the big explosions had stopped. It now sounded like a large bonfire. I moved along the edge of the house then crossed twenty feet of grass to crouch behind a hedge. Maybe eighty feet away, the men with their glaring flashlights marched up the street. Their whispering carried so well on the soft breeze that they might just as well have been shouting. Sprinting to a tree, then crawling behind a hedge, then kneeling beside a garage, I advanced along the street. From where I hid, I could see the dark barrel of Freeman’s rifle poking out from the basement window.

As I watched the white eyes of the torch beams travel up and down the street crossing and tangling and illuminating bushes and lawns, I realized that I was about to do what I was created to do. I was designed for combat and for killing. This would be murder. These men had no chance of saving themselves. I recounted their flashlight beams. There were five of them.

Freeman and I needed to kill these men so quickly that they would not make a sound. There might be another party of five searching the next street and another five on the street after that. There might be an army of thirty or forty men waiting to hear what happened with these five scouts. I remembered the soldier with the rocket launcher slung over his shoulder. Now, with Freeman hiding in the basement of a house, that rocket launcher was worth a dozen machine guns. Fire a rocket at a bungalow like the one in which Freeman now hid, and no one could possibly survive the attack.

“I’m not sure what we’re going to do about that damn tank,” I heard one of the men say. “Maybe we can take it apart and rebuild it on the other side.”

“What? And carry the parts? That specking thing must weigh one million pounds. Just them treads weigh a ton!”

“What about fuel?” a third man asked. “They got the depot.”

“Shit, there’s more gas,” the first man said. “It’s a big base. There’s got to be more fuel.”

They were so wrapped up in their conversation that they did not even notice when the man in the rear got hit. He had been walking a good twenty paces back from the rest of the group. Freeman picked him off with a shot to the head, and he fell in the deep grass. No one even looked back for him. Freeman’s next shot was not so skillful. He hit the man in the head, but the man managed to yelp as he died. He staggered forward and dropped his machine gun on the road. It did not fire, but the racket was jarring on this otherwise silent street.

I fired my pistol and hit the two men closest to me. The green beam caused their torsos to burst. The kills were neither silent nor pretty. Both men dropped their guns, causing more racket. The last man turned and tried to run. Freeman’s silent shot struck him from behind, tearing away two-thirds of his neck. He flopped to the ground as if there was not so much as a rigid bone in his body.

Others would come. If they did not locate us, they might burn the entire neighborhood down. We needed to put a couple of miles between us and Callahan’s remaining soldiers before daybreak. We started down one street, saw men with lights, and then went down the next street. We zigged and zagged our way through the sleepy officer’s suburb hiding beside houses and sometimes dashing into backyards. Like the base itself, this housing area was a maze. Roads formed cul de sacs and concentric circles. Tall brick walls separated communities that should not have been divided. Coming to an intersection of two small roads, I heard voices and stopped Freeman. I pointed to a hedge, and we both hid behind it. Seconds later, a parade of forty or fifty men walked by. These men carried rifles and pistols. They were not dressed in fatigues but in a variety of civilian clothes.

These men did not speak. They meandered ahead. They did not use flashlights or bright lights that would give themselves away. Hiding a mere five feet from these ghostly soldiers, I watched them pass then turned to Freeman. “Those aren’t Callahan’s,” I said.

“Scavengers,” Freeman said, “coming to see what caused the explosions.” He did not need to say more. The first signs of daylight showed on the horizon. The sky brightened behind distant buildings. We traveled through an exurb, then a suburb and finally the metro, winding our way through alleys and small streets. Once in the city, I had an idea about climbing down a manhole. I lifted the lid from the manhole, and Freeman watched skeptically. The problem was that we did not know where the tunnels might be collapsed. In the end we continued above ground.

We never did run into gangs as we passed through Safe Harbor. I saw a man once. He watched us from the top of a three-story building. He sat on the ledge of the building with his feet dangling over the edge, and calmly watched us walk. Whether he was resting or maybe a guard on watch, I could not tell. But he seemed to be more interested than concerned about us.

It took a day to reach the outer edge of Safe Harbor and another day to make our way down the highway. When we reached the vehicles we’d stolen, we hopped into Freeman’s van and drove to the spaceport.

I had not slept much since landing on New Columbia, neither had Freeman. We decided to rest for the night. He slept in his ship and I slept in the Starliner. As I made my bed, I found an old book with dried-up leather binding. With all that had happened, I did not immediately recognize it. Then I saw the words, Personal Journal of Father David Sanjines , and remembered reading the book the night that Bryce Klyber gave it to me. This was the diary of that Catholic priest who hated Liberators but made an exception for Sergeant Shannon. I reread the passage and wondered what this man would have thought about me.

Considering his prejudices, what would Father Sanjines have thought if he had lived to see the entire Republic fall? What would he think of the chaos in Safe Harbor? Liberators had not caused this entropy, though some had died trying to prevent it. As a priest, Sanjines would have agreed that evil can come from natural men. Would he also have agreed that good can come from synthetic soldiers?

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

While I slept, Ray Freeman went scavenging around the spaceport. Most of what he found was packaged food, cookies, candies, and pastries that tasted like plastic. He got it by breaking into vending machines. He loaded this food into a galley at the back of the Starliner. He also brought a few changes of clothes, some combat gear, and a couple favorite guns including the sniper rifle they gave him at Fort Clinton.

We had not yet opened the hangar doors. The lights under the wings of the Starliner cast a faint red glow around us. Other than that, the area around the ship was as black as space. For a man who prided himself in not caring whether he lived or died, I spent a lot of time fussing over safety checks. I examined the housings around the broadcast generator and the broadcast engine. I checked the instrumentation. I also refueled the Starliner, siphoning thousands of gallons of fuel from an underground tank outside the hangar. Space flight required very little fuel and the energy I needed for self-broadcasting was created by a broadcast generator, but atmospheric flight ate into my fuel supplies and I had no idea when or where I would be able to refuel.

Freeman sat silently in the copilot’s seat through much of this. The seat was a squeeze for him. It was too close to the controls. The wheel brushed against Freeman’s massive chest. He had to curl his tree-stump legs under his seat because the niche under the dash was both too small and too short to accommodate them.

Freeman sat in that seat, staring out the window and looking like an adult in a child’s playhouse. It took a moment before I realized what had so captured his attention. He was looking at his plane, which he had owned for years. With the Broadcast Network out, his ride could no longer attempt anything more ambitious than continent-hopping.

I knew better than to inquire about it. Ask him how he felt, and Ray Freeman would simply stare at you.

“Any suggestions about where to go?” I asked as I powered up.

“Delphi,” Freeman said.

“Never heard of it,” I said.

“You’ve heard of it,” Freeman said. “The neo-Baptists renamed the place. Before my father arrived there, the planet was called Little Man.”

“Little Man?” I asked.

“I was headed there before you called me.”

So much had happened over the last few days that I forgot all about Freeman’s family. They had set up a colony on Little Man. The U.A. Navy had sent a fighter carrier to the planet to tell them to leave. And then . . . and then the Republic went dark.

“A fighter carrier dropped in on them,” I said. “How long ago was that?”

“Four, maybe five days,” Freeman said. “Why?”

“I might be wrong about this, but if I remember correctly, it takes over a hundred hours to travel from the nearest broadcast disc to Little Man . . . and that is at top speed. If that carrier only left Little Man four days ago, it would not have made it to the discs in time to broadcast out.”

“Yeah,” Freeman said, rising to his feet. “I figured that. I’ll open the hangar.” He climbed out of the cockpit. The low ceiling of the Starliner was an uncomfortable fit for me, and I was only six-three. Freeman, who stood at least nine inches taller than me, had to bow his head, curl his back, and waddle sideways to wedge himself through the cabin. To climb in and out of the hatch, he had to drop into a low squat.

I turned on the landing lights as he walked across the hangar, bathing the floor in bright white glow. The door was still locked. Freeman pulled out his particle beam pistol and shot the locking mechanism, blasting a hole in the center of the door through which a beam of bright daylight stabbed. When Freeman tried to slide the tall metal door along its track, it still did not budge. There was a mechanical roller with heavy metal cogs along the top of the doorway, just above the track. Freeman shot the roller and it dropped to the floor. He tried to roll the door open again, and it still fought against him. This time he pulled his particle beam pistol and shot the track from which the top of the door hung. There was a loud yawning noise as the tonnage of the door, which was at least thirty feet high and a hundred feet across, pulled itself free from its supports. The metal door quivered in place for a few seconds, then twisted and fell flat against the tarmac outside the hangar. The resounding crash reverberated through the hangar.

A torrent of bright daylight flooded in through the gap that the door had once blocked. His expression still as inscrutable as ever, Freeman turned and walked back to the Starliner, pocketing his pistol along the way. He did not rejoin me in the cockpit but took a seat in the cabin. I drove out of the hangar, rolling over the fallen door, and took off. Streaming up into the horizon, I chanced a glance down at Safe Harbor. From here, the city looked no different than it had the first time I came. Five miles up and rising quickly, I could not see the burned buildings and broken highways. The atmosphere thinned and darkened as we entered outer space. I did not have to worry about radar or traffic controllers tracking me. As soon as we left the New Columbian atmosphere, I engaged the broadcast computer and worked out coordinates for Little Man. Lightning danced outside the cockpit, and we emerged in the Scutum-Crux Arm a short thousand miles from the target.

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

Something in my programming had gone haywire and rendered me sensitive to the loss of human life. I still had the ability to kill, but it bothered me. Now, seeing Little Man, my head filled with memories of the Marines who died in that awful battle. I remembered Captain Gaylan McKay . . . the personable young officer over my platoon on the Kamehameha . I remembered the ranks of idealistic Marines and the march that led to their deaths. Strange as it sounds, I felt an involuntary shiver. What I should have felt was anger.

“When was the last time you saw your family?” I asked.

“It’s been five years,” Freeman said.

“This should be some homecoming,” I said.

“They don’t want me here,” he said. He did not elaborate. Freeman never elaborated. We kept flying into the green and blue horizon. Using sensors to search for metal and heat, we located the colony in a plains area. They were building their settlement on the edge of a forest and not far from a clear-water lake. In the distance, a mountain range filled the horizon. It was not on the same continent on which we fought that final battle.

The first thing we saw was acres and acres of plowed land. Beyond the fields was a small and primitive town that consisted of warehouses and unfinished apartment buildings. Even when the apartment buildings were complete, they would only be temporary shelters meant to hold people for days or weeks. Work had already begun on larger, more permanent buildings as well.

Women and children in simple clothing emerged from the temporary shelters as we landed. Men in overalls came from the construction projects and from the fields. If there was one thing that stood out about the people on Little Man, it was their industrious nature.

The people did not approach my ship, but huddled together inside the borders of their town. They did not seem scared. They simply stood in place, curious to see who we were.

“I guess the welcoming committee has arrived,” I said, and turned to see that Freeman had already opened the hatch. I followed him out.

“I should have known it was you,” a man called in a voice drenched with loathing. Freeman did not answer.

When I stepped out of the ship, there was a collective gasp. I guess they were used to a seven-foot-tall black man, but the sight of a clone was strange and new. I turned to look at these people and got a jolt of my own.

I had always taken it for granted that Ray Freeman was unique in the universe. He was, I thought, a one-of-a kind, like me. It never occurred to me that he could have come from a colony of men and women similar to himself. The men and women of Delphi were very much like Freeman. They were tall and dark-skinned. One of the woman later told me that they were pure-blooded African Americans. As far as I knew, they were the last people anywhere who referred to themselves as American at all.

“What are you doing here, son?” an old man asked. The man was tall and solidly built, but he looked underfed. He did not have Ray Freeman’s broad, wrestler’s physique. His shoulders were square, his back was erect and the parts of his arms that extended beyond the short sleeves of his shirt looked strong and well formed. He removed his hat. An even layer of gray berber hair covered his head. His dusty skin was far darker than Ray’s, almost a true black. It looked dry and leathery from decades of toil under a burning hot sun. “What are you doing here, Raymond?” he repeated. Silence hung between Freeman and his father like a curtain. I could almost feel the hostility. The people around the old man stood silent and staring. They stood unflinching and unmoved. Like Freeman’s father, these people were tall, dark, with skin that had dried to leather in the sun. Freeman took nearly one minute before he began to speak; and when he did speak, he spoke so quietly I could barely hear what he said. “The Broadcast Network was destroyed.”

“Destroyed?” the elder Freeman repeated. For the first time since we landed, the people behind him showed concern. They began to speak quietly among themselves.

“I wanted to make sure you were okay,” Freeman said.

By this time, however, the elder Freeman’s attention was no longer on his son. He had turned to me.

“You are a friend of Raymond’s?”

I nodded, wondering if Ray Freeman had ever really had a friend.

The old man turned back to Freeman. “How could anybody destroy the Broadcast Network?” It was a fair question. In U.A. society, the Broadcast Network was a given as constant as sunlight and water. No one, with the exception of Rear Admiral Thomas Halverson, had ever stopped to consider its fragile nature.

“There was a war. Some of the arms declared independence,” Freeman said. His father should have known this. Of course his father would have known this. It was the biggest news in history. And yet, looking at the old man’s surprised expression, it became clear that he had not known about the war.

“A civil war?” the old man asked.

“It’s a civil war if you lose,” Freeman said. “It’s a revolution when you win.”

“They won?” A younger man stepped forward. This man was far shorter than Freeman and not as broad along the chest and shoulders. He had a wiry build, but he looked athletic.

“They destroyed the Mars broadcast station,” I said. “Without the Mars discs, the entire system shut down.”

“For how long?” the old man asked, turning back to Ray. “How long before they fix the broadcast station?”

“They won’t fix it,” Freeman said.

“Of course they’ll fix it,” the younger man said. “They’ll send over the fleet . . .”

“Earth doesn’t have a fleet,” Ray said. “The Earth Fleet was defeated, and they can’t send ships from other fleets without the discs.”

The older Freeman stood still as a statue, his gaze boring into his son’s eyes and then mine. “Man has finally turned his back on us,” he mumbled. Then louder, he added, “God has cleared the way for us to stay in this promised land.”

There were 113 people living on Delphi. I know the exact number because the entire population, or perhaps I should say congregation , assembled in their meetinghouse—a building meant to be used as a sleeping and eating facility during large evacuations. The people sat on plastic benches. Archie Freeman, Ray Freeman’s father, looked down on the congregation from behind a very plain pulpit, over which hung a fiberglass cross.

There were two women with infants in the congregation. One woman threw a blanket over her shoulder and nursed her child. You could hear it sucking when the conversations lulled. The other woman cradled a sleeping baby in her arms, rocking it softly as she stood in the back of the meetinghouse. I noted the tenderness with which she treated the child and envied it. Having grown up in U.A. Orphanage #553 with other clones, I had never seen tenderness of this kind.

The people of Delphi attended this meeting as families. Husbands and wives sat together with their children. Near as I could figure, there were eighteen extended families. The whole of them only filled the first four rows of the meetinghouse. For the most part, the next twenty rows sat empty—an ambition unfulfilled.

“My son says that we are in danger,” Archie Freeman began the meeting with those words. He stood at his pulpit as austere and grave as any man I had ever seen. He had washed and changed his clothes. He wore a black suit, white shirt and black necktie. He dressed like a businessman. Now that he had washed up, the color of Archie Freeman’s face was almost onyx. His skin had the texture of parched leather, his reward for fifty years of trying to start colonies on uninhabitable planets. Having finally landed on a productive planet with plenty of water and healthy soil, he did not want to leave.

Archie was bald at the top, with a very short layer of gray-white hair that looked like a macramé cowl. His eyes were bloodshot from his day out in the sun.

“Raymond, come up and speak your piece,” the elder Freeman said.

Ray, who had been sitting with a woman near the back, stood and walked to the front of the chapel. No one reached out to shake his hand or pat his back. Seeing the reception these people gave him, you might have thought he had never lived among these people. But he must have lived with the people before they moved to Little Man. He was their 114thcitizen. He probably knew every one of them by name. Archie Freeman did not step away from the pulpit as his son joined him on the stand. The two men stood a few feet from each other. Ray, as I have mentioned before, stood at least seven feet tall. His father appeared to be three or four inches shorter than him, and a lot thinner.

“Tell them what you told me, son,” Archie Freeman said in his handsome baritone.

“There was a war,” Freeman said. “Four of the arms wanted to leave the Unified Authority. They had a fleet of self-broadcasting battleships. They attacked Earth and defeated the Earth Fleet.” Here he paused for just a moment. “And they destroyed the Mars broadcast station. Without the Broadcast Network, Navy ships cannot travel between systems. The ship that came here a few days ago is stuck out here, too. It will be back.”

Until that last sentence, the room remained silent. When Freeman told them that the fighter carrier would be back, the people started talking among themselves.

“How can you know that?” an old man on the first row yelled. It sounded like a challenge.

“It takes four to five days for a carrier to fly here from the discs,” Freeman said. “The one that came here didn’t have enough time to reach them before they went dark.”

I heard shouting and crying. I saw men yelling at each other, then turning and yelling at the women beside them, and I realized that these people had just been told that their world was doomed. Archie Freeman put up his hand to calm the crowd, but the commotion continued. “Raymond and his friend have offered to move us to another planet.”

That last sentence quieted the crowd.

I had this strange feeling, like I was intruding on a family matter. I was an outsider. Hell, Ray was an outsider, and he was born and raised among these people. They had something special, something I could never have. Looking around the congregation, I knew that even if I moved in among these people, I would never be one of them. They were family . . . and I was a clone. I took one last look at Ray standing tall, mute and confused, and maybe even intimidated, on that stand. Then I quietly got up and left the meeting.

It was early evening. The sun had set but the sky was bright. All the blue had faded from the sky. The horizon showed orange and red, and the sky above me was white. The temperature had dropped to a comfortable seventy degrees. Little Man was always a hospitable planet. It was the inhabitants that worried me.

A soft breeze blew in from the fields, carrying the scent of freshly turned soil and fertilizer. I stood and stared at the ground with its rows and furrows. Beyond the fields, a red and green forest stretched out as far as a man could see.

“It looks so pretty at night,” a woman said. “I almost forget all the sweat and hard work that goes into it.”

“It’s beautiful,” I said, turning back. The woman walked in my direction. She had brown skin. It was the same color as Ray Freeman’s skin, but more tanned. Her skin was parched, but not as badly as Archie’s.

“You’re not going to stay for the meeting?” I asked.

“They don’t care what I have to say any more than they care what Ray has to say. We’re pariahs, and decision-making is a job for God’s elect.” She wore a long-sleeved white blouse and her plain gray skirt went all the way to her feet. These must have been her church clothes. They looked clean and pressed.

“I’m Ray’s sister, Marianne.” With this, she put out her had for me to shake.

“Wayson Harris,” I said, shaking her hand.

Her palm and fingers were hard and rough, far rougher than mine. I had climbed ropes and dug trenches in school, but the life of a Marine is mostly spent in combat armor. This woman had spent her days plowing and digging with tools, not equipment. Her palms were calluses. She had broad, manly shoulders, and her wrists were as thick as mine. She stood only an inch shorter than me. Her lips and skin were almost the exact same color. Her hair was black and long. It hung down to her waist. She was elegant and strong, and I thought that in the proper setting, dressed in soft clothes with her hair done up, she might be beautiful. In another world, where she was perfumed and pampered, she might be exquisite.

“Why are you and Ray outcasts?” I asked.

“Raymond couldn’t stand living in a religious colony. He never believed in Jesus, and he and Archie hated each other. When Raymond was old enough, he caught a ride on a supply ship and got as far away as he could. I think Archie was glad when he left.” I noted that she called her father Archie, as if he were a friend or an acquaintance. “He wanted someone to follow in his footsteps and lead the armies of God. That wasn’t Raymond.”

I tried to imagine Ray Freeman as a minister and found that I could not picture him without his armor and his guns. “Does Archie know what Ray does for a living?” I asked.

“We don’t talk about that,” she said.

“But you stayed,” I said. “What makes you a pariah?”

“I stayed, but my husband didn’t. I have a little boy named Caleb. He’s in the meeting, sitting with his grand-mother. I don’t know how Jesus feels about divorced women, but I can tell you how the women on this planet feel about them. If I so much as talk to any of their men, tongues start wagging.”

“So you’d be glad to get off this planet?” I asked.

“Mr. Harris . . .”

“Call me Wayson.”

“Wayson, I don’t think we’ll leave this planet. Our little colony might not look like much, but we’ve worked night and day to build it. Delphi is a lot nicer than the other planets I’ve seen. Frankly, Wayson, starting all over again scares me more than that carrier out there.”

Easy to say when you haven’t seen what one of those ships can do, I thought. But I did not say this. Darkness spread across one side of the horizon. The air continued to cool. I felt a pleasant chill in the breeze. “You haven’t been here that long. Your crops haven’t even sprouted. How hard could it be to start over again?”

Marianne laughed and smiled. Her teeth were white and even. “That field . . . We worked on that field night and day. We still haven’t cleared it properly. We got out most of the rocks, but there’s a lot more we can do. We’ve planted almost every seed we have in that field, Mr. Harris.”

“Wayson,” I said.

“If we leave that field . . . I can’t speak for everyone, Wayson, but the people I have spoken with would rather die than leave.

“And it’s not just that we are neo-Baptists. We used to do this for the church, but that ended a long time ago. Now we’re colonists first and neo-Baptists second. The church wanted to create colonies just like the Catholics. That was their deal. Us, we wanted to make a home. Now that we finally have a planet that will sustain us, you can’t really expect us to turn it over.”

“Why did your husband leave?” I asked.

“He thought there must be a better life on other worlds, so he flew off on a supply ship, just like Raymond. He asked me to come with him, but I didn’t want to go. I believed God wanted us to build a colony. I had my boy, my Caleb, and I wanted him to grow up in a righteous colony. I believed that God would bring us to our promised land, our Goshen. I believe he has.

“Do you believe in God, Mr. Harris?”

There was a loaded question. She had to have known that I was a clone. I thought about the conversation about clones and souls that Tabor Shannon had with that priest on Saint Germaine. “I don’t know if I believe in God,” I said. “And I don’t know if he believes in me.”

It was not love at first sight. It probably wasn’t even love, but I felt attracted to Marianne. I liked her. I only had one other woman with which to compare her, a girl named Kasara whom I met on leave. Kasara had been beautiful, irresponsible, self-centered, and fun. She was a girl. Marianne was something else. She was raising a boy on her own; she worked hard on a farm; and she kept her head straight in a lethal situation. If Kasara lived to be a thousand years old, I doubted she would ever grow into the woman Marianne had already become.

“It doesn’t seem like anybody here knows about the war,” I said.

“We hear things. Well, truth be told, we all heard things. The missionaries that flew us here told us about it, but it didn’t sound serious. It didn’t sound like more than a little uprising.”

“You never followed the war on the mediaLink?”

“And what would that be?” she asked.

“What would what be?” I asked feeling thoroughly confused.

“You said something about following the war on something or other.”

“The mediaLink,” I said. “That’s the news source.”

“I can’t say I have ever heard of it,” she said.

“It’s too late now,” I said. “It receives communications signals sent through the Broadcast Network. You do know about the Broadcast Network.”

“Yes,” she said, feigning that she was offended. “I know about the Broadcast Network.”

“When they destroyed the Network, they shut down communications as well as travel. Close as I can figure, it would take a laser signal 70,000 years to get from Earth to Delphi. Without the Broadcast Network, they might as well be sending smoke signals.”

“So it’s all true. The entire Republic is shut down,” Marianne said.

“Everyone is on their own,” I said. “It’s just that some planets are better off than others.”

“So why did you come here?” Marianne asked. “You have that self-broadcasting ship. You can go anywhere.”

“I asked Ray where he wanted to go, and he said he wanted to come here.”

“And you went where he asked. ‘Where you go, I will go . . . Where you lodge, I will lodge also . . . Your people shall be my people.’ You’re a modern version of Ruth, Mr. Harris.”

I didn’t know what that meant and I had never heard of Ruth, but Marianne’s smile charmed me.

“Maybe we should look in on the meeting,” I said. “I don’t want to start tongues wagging.”

“Are you worried about my reputation?” Marianne asked. “Don’t worry about me. Those tongues are already wagging. That’s how life goes on a small planet.”

“How did it go?” I asked Freeman as we settled down to sleep in the Starliner. Archie could not find beds for us. He could not find sheets for us, but he did have pillows.

“They don’t want to leave,” Freeman said. He stripped off his chest armor and stepped out of his coveralls. Stripped down to his boxers, he stretched out as best he could. “They think they can talk their way out of this.”

“They want to reason it out with a fighter carrier?” I asked.

I had never seen Freeman stripped down. The massive muscles in his chest and arms looked powerful, but not defined. He did not look like a bodybuilder. He had the build of a blacksmith or a construction worker. “They think God delivered them here.”

Marianne had said as much when we were talking. Images of Marianne ran through my head. Was I infatuated, I asked myself, or just lonely? So many new emotions clouded my thinking since the fall of the government that I no longer trusted myself. I wanted to ask Freeman about his sister, but I was afraid of tipping him off to my thoughts.

We slept on reclining seats that only reclined to a forty-five-degree angle. The weight of our heads never left our necks.

“You landed on an engineered planet once, didn’t you?” Freeman asked.

“Ezer Kri,” I said. “That’s where we caught Kline. You were there, remember?”

“No, an unpopulated one,” Freeman said.

“Ronan Minor,” I said, remembering the mission.

“It wasn’t called something Kri?” The term kri denoted a planet with an engineered atmosphere.

“It was a shitty place.” I rolled over in my seat and hit the panel to turn out the lights. “What do you think is happening on Earth?”

Freeman thought about this. “Depends who comes out on top. If the Confederate Arms win, they’ll fly in armies. The outer arms always had good ground forces, they just couldn’t protect them.

“If the Mogats made out, it will be worse. The Mogats, they don’t care about colonizing. They don’t want to occupy Earth. All they want is to erase every vestige of the Unified Authority.

“It’s only been a few days . . . The Mogats and the Confederates may not be through killing each other yet,” I said.

“Harris, you think we could relocate these folks on Ronan Minor?”

“They wouldn’t like it,” I said. “It was a jungle and the only life on it is cockroaches and rats.”

Freeman understood what I meant immediately. Ships are not allowed to land on engineered planets until they are declared stable. When squatters trespass on these planets, vermin escape from their ships. On a planet like Ronan Minor, where the vegetation is profuse and there are no natural predators, rat and cockroach populations proliferate.

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX

Talk about your flat-world society . . . Archie Freeman did not believe that there could still be a fighter carrier floating out somewhere around his planet. It took some arm-twisting, but Ray talked him and three of the elders into a trip to the broadcast discs. We would show them that the discs were dead, do a radar sweep to see if we could find any trace of the fighter carrier, and maybe look around. Ray Freeman did not come for the ride.

Archie and his brethren were novices at space travel. They had never been in a self-broadcsting ship, and the idea of it scared the hell out of them. The old man had to brace himself just to climb into the copilot’s seat of the Starliner. He did not complain or ask me to be careful. He looked around the cabin nervously and tried to sound comfortable.

“You know,” he said in a confidential tone that suggested this was a big confession, “I always wondered what it would be like to go up in one of these.” He laughed. Now that he was in true confession mode, he went on. “Self-broadcasters remind me of the early days of airplanes and daredevils flying through barns. Ho, ho, ho.” He laughed a beautiful baritone laugh.

The elders, men in their thirties if I had to guess, sat in the first row of the cabin. They strapped themselves in and did not speak. They seemed to share Archie’s outer fear of self-broadcasting ships not his inner enthusiasm.

“Do you understand how self-broadcasting works?” I asked Archie as we strapped ourselves into our seats. I, of course, only had the shallowest grasp, but a farmer/colonist like Archie would not care about the specifics. All he cared about would be the base fundamentals.

“It will be just like flying into a broadcast disc,” I said.

“The broadcast discs were destroyed,” Archie said.

“Not destroyed . . . just unplugged,” I said, for lack of finding a better way to explain myself.

“They don’t have power?” Archie clarified.

“Right. This ship can broadcast itself. There will be an electrical field around the ship right before we broadcast. It’s supposed to be there. There will be a bright flash, and when we come out, we’ll be near the broadcast discs.”

“What if we run into that carrier?” Archie asked as I powered up my console.

“We could,” I said, “but I’m betting that they went to the discs, found them dead, and have already turned back toward Little Man.”

“Delphi,” Archie said.

“Excuse me?” I asked.

“We call the planet Delphi. ”

“Right. Sorry.”

“What happens if we run into that carrier? I don’t see any guns on your ship.”

“I don’t have any.”

“Can you outrun a carrier?”

I hit the button to start charging the broadcast engine. “Not a chance. Those ships hit thirty million per hour. I might be able to do six million miles at best.”

“So what will we do?” Archie asked.

“Look, Archie, it’s a big galaxy. You don’t run into ships out here by accident. You can go out looking for other ships and never see them. If you and I were the only people on Delphi, what do you think the chances would be of our accidentally running into each other? The galaxy is a billion times bigger than Delphi.”

We took off at a steep angle and left the atmosphere quickly. Now that we had left the ground, Archie gripped the sides of his chair, his bony knuckles curved in like cats’ claws. He seemed unable to look away from the window. The sight of the planet below us seemed to hypnotize him. I looked back in the cabin and saw that the three elders had the same reaction. They leaned into the nearest windows and stared.

“Okay, I am going to broadcast us now,” I said as I brought up the tint shield.

“What’s that?” Archie asked. “The window went black.”

“It’s a tint shield. It protects your eyes,” I said. “Things get bright out there when we broadcast. Unless you tint the windows, the brightness will blind you.”

“Oh, okay,” he said, sounding somewhat reassured.

Strings of electricity showed through the blackened windscreen, then the flash showed through. Archie was startled. He looked around the cockpit nervously. His legs, which did not fit behind that seat much better than his son’s, went stiff, and he lifted himself part way out of his chair. In that moment of fear, he lost partial control of his body. He did not wet himself or drop a load, but he farted something loud and smelly.

I had started to say, “We’re here,” but seeing the shocked look on Archie’s face, I could not stop from laughing.

“Oh, you think that’s funny?” Archie asked. “You goddamned clone.”

Some things you regret saying even before you finish saying them. I saw embarrassment and anger on Archie’s face. He settled back in his seat and stared straight ahead.

Out of habit, I started up the generator to charge the broadcast engine the moment we arrived. That habit saved our lives.

We arrived just a few miles from the broadcast discs and drifted over to see them. Coming to an almost dead stop, I took the Starliner around the defunct discs.

“Those are the discs?” Archie asked.

He probably did not see the discs when he came to Delphi. He and his fellow settlers had most likely traveled in a cargo ship. Even if they flew in a commercial craft, the tint shields would have been up long before they came this close to the discs.

“That is the broadcast station,” I said.

“You fly into it?” Archie asked.

I remembered that he lived on a planet without modern conveniences. “You fly toward it. It sends out an energy field to transport your ship.”

“I see.”

“If the discs were live, they would have a white glow. There would be traffic lights and warning lights along the top. There’s not so much as a volt of electricity in this station.” My broadcast gear included an enhanced radar display. As I reached to turn on the display, the Harrier buzzed us. It was a gray-white blur that streaked past the cockpit and totally vanished.

“Good God! What was that?” Archie yelled.

Red lights flashed in the canopy and on my heads-up display. A warning sign flashed on my instruments. Alarms buzzed. I switched on the radar with one hand and pulled the wheel sharp to the right with the other. “Hold on,” I yelled.

“What’s going on?” Archie yelled. It was not a scream. He had control of himself. “What was that?”

“You asked me what would happen if we ran into that carrier,” I said. “We just did.”

He pressed his face against the cockpit and stared out the window. “I don’t see anything.”

“Archie,” I said, as I stared into the radar, “that ship travels thirty million miles per hour. They could come right up our nose and ram us before you see them if they wanted.”

“Do they want to kill us?” Archie asked.

“We’d already be dead if they did. That was a fighter. The pilot could flame us with a single shot if he wanted.” I glanced at the broadcast gear. It would need another two minutes of charging before I could use it.

The Harrier did not came upon us from behind. It slowed so that we would see it, flashed over the top of the Starliner, and vanished into space. The radar tracked its path.

“They’re not going to shoot us yet,” I said.

“How do you know that?” Archie asked.

“They’re stuck out here and the broadcast station is down, right?” I asked. “They’ll want to know how we got here before they start shooting. If they figure out that we’re self-broadcasting, they’ll want to capture our ship.”

“Unidentified space craft, this is the U.A.N. Grant . Identify yourself.”

“The Grant ,” I whispered to myself. I knew the ship.

“What are we going to do?” Archie asked.

“They want to know how we got here,” I said. “I’m going to show them.” An amber light winked on above the broadcast engine to show that it was ready. I had already programmed in the coordinates for Little Man, and now I initiated the broadcast.

They had no way of knowing where I broadcasted to, but they could certainly make an educated guess. If I had come from within this galactic sector, I could only have come from Little Man—Delphi as Archie called it. That was the only habitable planet in the area.

With that short visit, I set events in motion. I started the countdown. Archie could no longer evacuate his colony. We had time to fly his people to safety, but he would need to leave his buildings and equipment behind. But Archie did not want to leave. He believed that God had deeded him Little Man and that God would protect him. All he needed was faith.

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN

“Raymond was right,” Archie said in a soft voice to his people. He looked dejected. His arms hung at his side as he spoke, his head hung at a slight tilt. “That carrier did not make it through the broadcast disc. It will not arrive at Delphi today, and it may not come back for a week; but sooner or later, it will return.”

The congregation let out a collective gasp. “Deliver us, Lord,” one woman yelled. She stretched her arms above her head, her fingers extended, imploring.

I sat alone in a corner in the back of the town hall ready to leave. Freeman sat with Marianne and her son. They sat one row behind the rest of the congregation. They were with the people but not part of them.

“Raymond believes that we should leave this planet. He believes that the Philistines are at the gate, and we must abandon our promised land.

“God has promised us deliverance. We will not abandon our planet. I have seen the enemy with my own eyes. His fighters are as fast as light. But we must not fear the puny arm of man, for God will protect us.”

As the congregation let out a collective hiss, Freeman looked back at me, and our eyes met. In the silence that passed between us, we communicated disbelief.

If they wanted to call Little Man their “promised land,” well, they had the right to interpret it any way that they wanted. Saying that God would deliver them from the Grant , however, that was bullshit. No one could deliver them from the Grant , and the only ones who might try were the “goddamned clone” and the colony pariah.

The thing was, I couldn’t leave them. Klyber once told me that military clones were programmed with an altruistic streak. We were made to serve and protect, especially when it meant killing enemies of the Republic. But now my programming was twisting in on itself, I was programmed to fight for the Unified Authority. In the back of my mind, I constantly reminded myself that the Unified Authority no longer existed and that whoever was flying the Grant , they were not receiving orders from Washington D.C. I did not know if I could convince myself of this. I would not know until I either performed in battle, or froze because my programming would not let me continue.

I watched these people and I hated them. I regretted coming to Delphi. All of the anger I felt for the Unified Authority now focused itself on this congregation. And yet, none of them had done anything to harm me. Not even Archie.

Archie launched into a prayer. In that prayer he gave thanks for the planet of Delphi. Still praying, Archie said that Ray and I were led to the planet by God so that we could be instruments of deliverance. We were “tools in God’s hand.”

When the meeting ended, I asked Ray how he could ever have lived with these people. He shrugged his shoulders and walked away.

“Wayson,” Marianne said as she watched Ray leave, “this is Caleb. This is my boy.” She rested her hands on the shoulder of a young man who stood just a tad under six feet tall. His head came up to my nose.

“Good to meet you,” I said, trying to sound like I was comfortable around kids. I did not know what to say to the boy.

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Harris,” said Caleb.

And then we had an awkward moment when none of us knew what to say next. Archie came and tapped me on the shoulder. “May I speak with you?” he asked.

I nodded, grateful for the escape.

Archie led me to a quiet corner of the building. We could see people filing out the door. No one came to speak with us. I think they could read in Archie’s posture that he had serious business to discuss.

“Mr. Harris, I owe you an apology,” he said. Speaking in that baritone voice, he sounded truly humbled. He looked down at the ground as he spoke and rocked back and forth on the soles of his feet. “I don’t know what came over me.”

As I heard this, I could not help but remember the journal entry that the Catholic priest wrote about Sergeant Shannon. “I should not have laughed,” I said.

Archie looked up at me and smiled. “It must have looked awfully funny . . . me farting with that stunned look on my face.”

I returned the smile. “It did.”

“Mr. Harris, you and Raymond did not need to come here. No one asked you to help us, but you came. And now, once again, we are asking you to extend your generosity.”

I put up my hand. “It’s okay. Coming here was Ray’s idea. You should thank him.”

“He says it’s your ship.”

I nodded.

“Well, I wanted to thank you.” Archie turned and started to walk away.

“Can I ask you a question?” I said.

“Anything,” Archie said.

“You don’t believe I have a soul,” I said. I did not really care about whether or not I actually had a soul. I had made it this far without one. But the prejudice bothered me. I had come to help these people. If they considered me less than human, that bothered me a lot.

Archie Freeman stood silent and still as a tree and stared into my eyes. He had dark brown eyes that had yellowed. His eyes were bloodshot and appeared tired and full of intelligence. Staring into those eyes, I decided that Archie Freeman might give in to prejudice, but he would never knowingly lie.

“No, son, I don’t believe you have a soul.”

“Science can create life, but it cannot create a soul?” I asked. “Is that what you believe?”

“Science cannot create life,” Archie said.

“I’m alive,” I said, “and I’m a work of science.”

“I am not trying to judge you, Mr. Harris. I’m sorry for what I said. It was an awful thing to say. I don’t suppose I can ever take it back. No man can tame the tongue. It is a little member that boasts great things.” I did not know if this last bit was poetry or philosophy or scripture, but Archie sounded sad as he quoted it.

“Don’t judge me, judge science. I crawled out of a tube, not a womb. What does your gospel say about that?” Yes, I was spoiling for a fight with a man who had come to apologize to me. I was mad. I was offended. I knew I was wrong, and I did not care.

“Mr. Harris, I don’t pretend to understand cloning. I am a minister, and I have spent the last fifty years of my life on barren planets cut off from men and the galaxy.”

“But you don’t think science can create life through cloning?” I asked.

“Cloning doesn’t create life, it duplicates it,” Archie said. “If I have a fire, and you hold a stick over the flames until it catches on fire as well, you haven’t created a new fire, you’ve simply borrowed a flame from me.

“They didn’t create life when they made you, Mr. Harris. They borrowed genes from one of God’s creations . . . somebody who had a soul. You got his hair and his skin, and his eyes, but I do not believe you got his soul. I don’t believe his soul was embedded in that DNA.

“Now I think it’s real nice that you and Raymond came to rescue us. And I am grateful that you have been so generous. You appear to be a man of great virtue, though if you are associated with my son, you are probably a professional killer. But unless science has identified the gene that holds the soul, I see no reason to believe that you are anything more or less than a temporal man . . . a body with an Earthly spark of life and no chance for eternity.”

I thought about Shannon quoting Nietzsche to that archbishop, telling him that no man has a soul. I thought about pointing out that there was a time when white men thought that black men had no souls. None of this mattered. I asked Archie what he believed, and he gave me an honest answer.

“I came to apologize for what I said, Mr. Harris. I am extremely sorry about what I said on your ship. I hope you will accept my apology.” Having said this, Archie turned and walked away.

“That’s not exactly what he told everybody else about you,” Marianne said as she came around the corner.

“You were listening?” I asked, feeling ashamed.

She smiled at me; and her dark eyes, so much like her father’s, seemed to stretch wider with her smile.

“He is my father.”

“And that makes eavesdropping alright?”

“Yes,” she hesitated and spoke slowly as if trying to make up her mind. Then, with more certainty, “Yes, it does.”

“What did he say to everybody else?”

“The night you landed, we held a town meeting.”

“I know. I was there for some of it. I left and you followed me and we talked.”

“No,” Marianne said, “that was an open meeting. After you and Raymond left, Archie held a closed meeting, just for the men.”

“And you listened in?”

“Do you want to hear what he said or not?”

“What did he say?” I asked.

“People were scared of you. They said that cloning is an abomination. Archie said that incest is an abomination.”

“That makes me feel better,” I said.

“You don’t understand. Do you read the Bible?”

“Do you follow current events on the mediaLink?”

“Wayson, you’re such an ass.”

“Sorry.”

“Have you heard of Lot?” Marianne asked.

“Sodom and Gomorrah,” I said. “His wife looked back and turned into a pillar of salt. You don’t need to read the Bible to know that story.”

“Do you know that after his wife died, Lot’s daughters got him drunk and seduced him? They had two sons and both sons created nations.”

“Unless they were cloned, I don’t see what that has to do with me,” I said.

“One of those nations was Moab,” said Marianne. “A woman from Moab married a Jew. Her great-grandson was King David.”

“So?” I asked. I had heard of David and Goliath. I knew he wrote the Psalms. “What does any of that have to do with cloning?”

Jesus was a descendent of David. Had it not been for Lot’s daughters, Jesus would not have been born.

“Don’t you see, Archie justified you? He said that righteous ends can come from evil means.”

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT

The errand was not dangerous. All I was doing was broadcasting out to the middle of nowhere to take some radar readings and locate the Grant. I would not broadcast anywhere near its course, and unless they were looking for a broadcast signature, they would not detect me. If they did detect me, I would broadcast out before they reached me. If they reached me, they still wanted my ship intact. They could not risk shooting at me.

Ray came into the cockpit. Marianne loaded some food in the Starliner’s galley as I prepared to take off. The last people on the Starliner were Archie and Caleb, Marianne’s son. Over the last few days, Caleb had become my shadow, my helper, and my unofficial second-in-command. The boy was twelve years old, far too tall for his age, and headed toward another growth spurt. He liked to ask questions and watch his surroundings with great curiosity.

“Where do you think you’re going?” Marianne asked.

“I’m going along for the ride,” he said.

“You’re not going anywhere,” Marianne said.

“That’s what I told him,” Archie said.

“He’s with me,” I said.

She stared at me as if making sure I was serious. Caleb grinned like a child and squeezed around her as he made his way toward the cockpit. Marianne gave me a nasty look and climbed out of the Starliner.

“Go sit back there,” Ray said, pointing back to the cabin. Caleb and Archie sat on the same row. Caleb sat by the wall and stared out the window. Archie sat by the aisle and watched Ray and me.

“He’s adopting you,” Ray said. “You know that, don’t you?”

Taking a break from my instruments, I looked back at Caleb. I could only see the back of his head. I imagined that he was smiling, excited to fly into space.

“I don’t know much about families,” I said. “Is that what they call it?” I flipped a switch and brought the controls on line. I would take off in another minute.

“When a fatherless boy starts following you around, he’s looking for more than a friend,” Ray said. He glanced at Marianne, who was standing in the door of the meetinghouse. “She and Caleb are alone. Unless you want to live here on Little Man, you’d better let Marianne know you’re not here to stay.”

“You lost me,” I said. “Let’s square things with the Grant, then we can talk family.”

So Ray sat cramped in his seat and watched me. I stole a peek at Caleb. Had he pressed his face into the window any harder, he might have broken the glass. Seeing the boy made me laugh.

“Harris,” Freeman said, “this colony is a different world from your old clone farm. Nothing goes to waste here.”

“Meaning?” I asked.

“Marianne is looking for a husband,” Freeman said. “Her boy needs a father and you’re available.”

“I’m a clone,” I said.

“You see any other options?” Ray asked.

Stewing over Freeman’s warning, I looked back at Caleb. Archie was glaring at him, but he looked out the window and pretended not to notice. So now Ray wanted to play the role of the protective brother. I did not want to settle down on a cozy little planet with a family. It might have been my military upbringing or the neural program that made Liberators what they were, but I could not imagine life on a farm.

“She could come with us,” I said, thinking I had found a workable alternative. “We could take them to Earth or to . . . some other planet.”

Freeman shook his head. “She doesn’t want to get out. She wants to bring you in.”

“Ray, the boy is just coming along for the ride,” I said.

“Just know what you’re getting into,” Freeman said. “Marianne isn’t just scrub you met on the beach.”

Having delivered his warning, he left the cockpit and climbed out of the ship. His job was to scout the area around the farm. We needed to know where the Grant would send its landing party and how we could defend ourselves.

“You want to sit up here?” I asked Caleb.

His smile brightened and he trotted into the cockpit. He sat in the copilot’s seat.

Archie stood hunched in the door of the cockpit. Caleb and he watched every move I made as I pressed buttons and flipped switches. “What is that for?” “How about that one?” Caleb asked questions like a six-year-old, but he stored up the details like an adult. Archie watched in silence. When I powered up the broadcast computer, Caleb’s face lit up. “What is that?” he asked.

“This,” I said, “is the reason we can still travel when the rest of the galaxy is stuck in one place. This is a broadcast computer. It lets us go places without having to fly there.”

“Without having to fly?” he asked.

“I tell this computer where I want to go and it puts us right there.”

“That’s the part that scares me,” Archie said.

I was afraid Caleb would ask for details, but he didn’t. Instead, he hovered over the computer and pieced together how it worked. “How do you tell it where to go?”

I showed him how to translate interactive maps into coordinates. “Going to a planet is easy. The computer has coordinates for every star and planet in the galaxy.” I thought I would impress the boy. I mostly ignored Archie. “The hard part is if you want to fly to a pinpoint location, like a certain spot right above a planet. You don’t always aim at something big like a planet. Sometimes you have to fine tune it.”

“Like into deep space?” Caleb asked. “Like where we are now?”

“There used to be a space station called the Golan Dry Docks,” I said. “It was top secret. If you wanted to broadcast yourself there, you needed to put in the coordinates yourself.”

And then I remembered a story that I thought he would find interesting. “You heard there was a war, right? That was the reason your uncle and I came to Delphi.”

“A war against Earth?” Caleb asked.

“Yes, and Earth had this giant ship called the Doctrinaire . It was bigger and stronger than any other ship in the galaxy,” I said. “It was so strong that it could destroy whole fleets of enemy ships. And it had special shields so no other ship could hurt it.”

“So Earth used it to win the war,” Caleb said, his eyes wide with excitement.

“No, Earth lost. The people attacking Earth destroyed that ship with a single shot,” I said. “And they did it with a computer like this.”

We spent two hours on this trip. Caleb and I spent the entire time talking. We could have returned the moment we finished taking the radar readings. Instead, I showed Caleb how the Starliner worked. This fine young man, this kid whose company I so enjoyed, I told him stories from the war. Freeman might have said that I adopted the boy back.

“How can you destroy a ship with a computer?” Archie asked.