13: THE GIBBET

Next day they travelled fourteen miles and spent the night uneventfully at Naksh. Zuno having determined on a late start to cover the last seven miles of their journey, they set off an hour before noon in a blinding glare.

The white, dusty road across the plain lay empty in the mid-day heat. Zuno dozed where he sat. Soon the Deelguy had slackened their pace to a mere dawdle, now and then surreptitiously passing a flask between them.

"They're not going to offer us any, the lice," whispered Occula.

"It's enough to make anyone take on bad," panted Maia, for the twentieth time wiping the sweat from the back of her neck. Her body, under her clothes, felt covered with a kind of paste of sweat and road-dust.

Her hair was full of dust and every now and then she spat a mouthful of gritty saliva into the road.

"Doan' keep doin' that," said Occula. "Just throwin' away moisture: you need it."

"Well, I'm blest if I'm going to swallow it," replied Maia.

"Gettin' particular?" panted the black girl. "I wouldn' say no to a pint of cold piss, myself. Never mind, banzi. We'll soon be there now—less than two hours, I'd say."

The girls had gradually edged away from behind the jekzha and were now trudging a little in front of it, on the opposite side of the road. Here, although there was no shade—for the baked, cracked plain, covered with sun-dried grass and withered flowers, was treeless for miles— they were at least out of the dust raised by the slaves and the wheels.

"Am I dreamin'," said Occula, "or is this soddin' road goin' uphill again?"

"Ah, that it is," answered Maia. "Funny, isn't it? You don't notice the slopes till you come to them. It looks flat in front, but then you find—oh, I say, Occula, what's that, look, up there on the top?"

"Jus' doan' talk to me, banzi, while I finish meltin'," grunted the black girl, lowering her head like a straining bullock as the slope grew steeper.

Maia, tottering and closing her eyes against the dust, felt ready to fling herself down by the roadside and be hanged to what might follow. She watched a grasshopper leap out of the weeds and travel twenty feet, gliding on brown-edged, rosy wings. "Wish I could do that," she thought. "S'pose they don't need to drink, else they couldn't live here."

Reaching at length the top of the long rise, the Deelguy halted, supporting the shafts on their backs as they leaned forward, drawing deep breaths. There was still no shade, but the, girls, past waiting for permission, flung themselves down on the verge. Occula's face looked as though it had been chalked in long, uneven smears.

Maia grinned. "You look like you was got up for the mumming."

Suddenly she broke off, staring in speechless horror at the rising ground on the opposite side of the road.

About fifty yards away, in front of a clump of sage bushes, stood a narrow, wooden platform, from which rose two stout posts, about ten feet high and as far apart. The top of the square was completed by a crossbar, deeply notched in four places. From each notch hung a short length of chain ending in a fetter.

The fetters were secured round the ankles of what had once been two men. The dried bodies, hanging motionless in the still heat, were indescribably ghastly, so dreadful as to seem unreal, like spectres encountered in nightmare or some drug-induced trance. The expressions of agony and despair in their crumbled, lip-retracted faces were no less appalling for being inverted, eyeless and half-flayed by insects and birds. Their lank hair was bleached almost white by the sun. The three arms still hanging below the heads were nothing but bundles of gray sticks, to which, here and there, adhered rags and fragments of flesh. One still ended in a fist of tight-clutched fingers: below the others, small, white bones lay scattered on the turf.

Maia, with an inarticulate cry, buried her face in her hands. At this moment, as though the abomination had power to pursue her and pierce whatever feeble barrier she could raise against it, the ghost of a breeze stole down the slope, bringing with it a vile, carrion odor.

Occula, after one brief glance, turned back to Maia, shaking her gently by the shoulder.

"Never seen a crows' picnic before, banzi? Come on, they woan' bite you, poor bastards. They might have once."

"Oh—" Maia lay retching and shuddering in the grass. "I never—"

"Gives you a turn the first time, doan' it?" said the black girl. "That's why they do it, of course. 'Come all you jolly highway rogues, this warnin' take by me. The crows have pecked my bollocks off, as you can plainly see. But once when I was young and gay, I used to—' "

"Oh, Occula, can't we go away from here?" Maia was weeping. "Whatever can they have done?"

"How the hell d'you expect me to know?" replied Occula. "Dropped a plate on a Leopard's toe, I expect, or made Queen Fornis's bath too hot."

"Or possibly even made indiscreet jokes about the Sacred Queen," cut in Zuno from the jekzha. "But," he resumed after a few moments, "if all of us were to repeat everything we heard, it would give rise to too much awkwardness altogether, wouldn't it?"

Occula, who, as soon as he spoke, had stood up and turned toward him, made no reply, merely standing acquiescently as though awaiting an order. Unexpectedly, it was one of the Deelguy who next spoke, jerking his thumb towards the gallows.

"Make—onnemies. No good. Too monny, finish."

"Certainly there is seldom anything to be gained by making enemies," said Zuno. "We'll stop here for a few minutes," he added, extending a hand to show that he wished to be helped down from the jekzha.

"Since there is no shade for miles, this place will do as well as anywhere else."

Having alighted, he sauntered away in the opposite direction from the gallows, while the Deelguy crawled under the wheels and began playing some game with tossed sticks in the dust.

"They're a nasty, cruel lot, these Leopards, by all I ever heard," said Occula, as soon as she was sure that Zuno was out of hearing. "Never mind, banzi; we'll take bastin' good care they never hang us up, woan' we?"

None the less, despite her indifferent manner and air of flippancy, she appeared by no means unaffected by the spectacle on the slope. Her smile, as Maia pulled her to her feet, seemed forced and unnatural, as did the four or five little dancing steps she took across the grass by way of beginning their stroll. When Maia caught up with her she was biting her lip and staring pensively at the ground.

"Yes, a nasty lot," she repeated. "And if you go to bed with a murderer, banzi, how sound can you sleep?"

"What?" asked Maia, frowning. "I don't understand."

"No; I'm the one who understands; may all the gods help me!" But thereupon she broke off and, drawing Maia round, pointed towards the purple-rimmed horizon.

"Look, banzi! Take a damn' good look! We've come far enough to see it, doan' you reckon?"

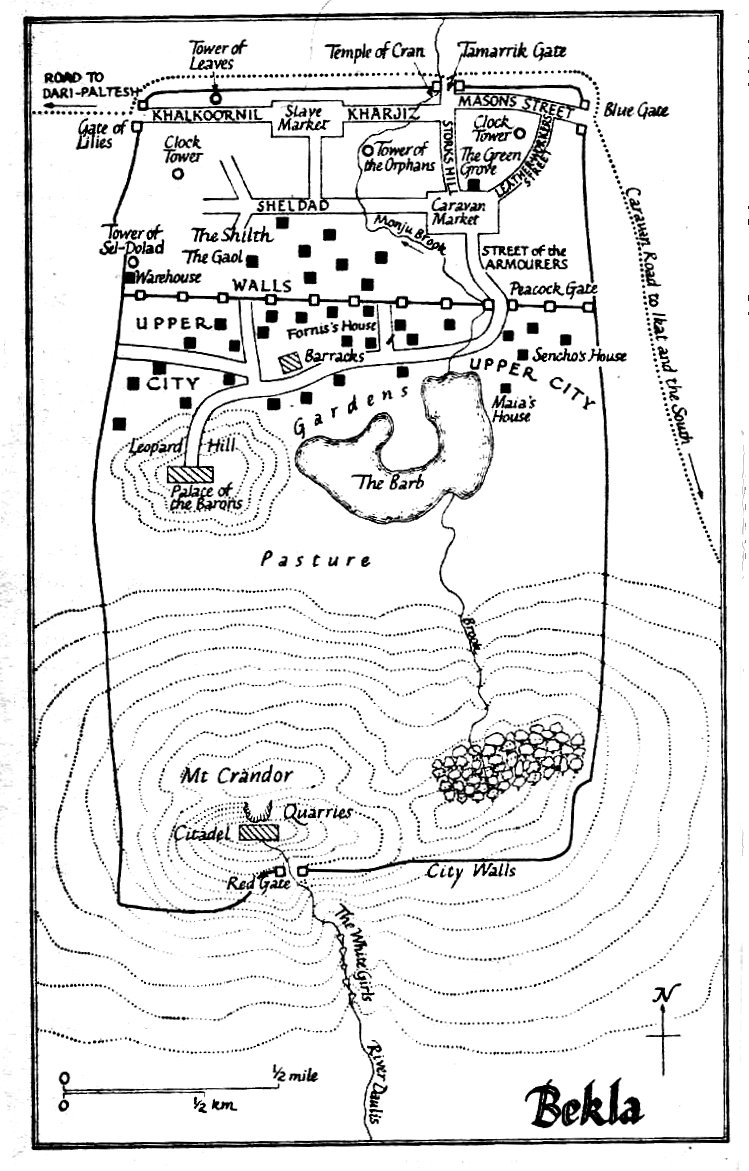

Half-closing her eyes against the glare, Maia gazed westward across the plain. Four miles away, a high, irregular mass cutting the skyline, stood the solitary peak of Mount Crandor, the mid-day brilliance throwing its ridges and gullies into sharp contrasts of sunlight and purple shadow. Encircling it, she could just make out a thin, darker streak— the line of the city walls, broken at intervals by the points of the watch-turrets.

To Crandor's right, immediately below the heat-hazed slopes, lay Bekla itself. Maia, who had never seen even Kabin or Thettit-Tonilda, stared incredulously at the mile-wide drift of smoke above the tilted roofs, through which rose the slender columns of towers taller than any trees; clustered together, as it seemed from this distance, like reeds in a pool. Above the city, between it and the lower slopes of Crandor itself, the Palace of the Barons crowned the Leopard Hill, its ranges of polished marble balconies catching the noonday sun and flashing gleams of light across the intervening plain. Even at this distance—or so, at all events, she thought—Maia's ears could catch, far-off and faint, a hum and murmur like that of bees about a hive.

"Turn Bekla upside-down?" she breathed at last. "Why, we'll just be goin' in there like—like coal to the blacksmith's, no danger!"

"Now stop it, banzi!" said the black girl quickly. "All right, I admit it's enough to poke your eyes out, sure enough; but stands to reason, doan' it, it's got to be like anywhere else—bung-full of randy sods with standin' rods? Get that into your head and keep on rememberin' it. You're not like a confectioner or a silk-merchant—someone people can do without at a pinch. You're like a baker or a midwife: life just can't go on without the likes of us. Whoever they are, they've got to be born, they've got to eat, they've got to baste and they've got to die."

"But I never imagined; it's so big!" Maia stared once more at the distant city with its array of tapering spires.

"Well, that's what the priestess said to the drover, but she found she could manage it all right after a bit. Look, there's old Puss-arse coming, see? Let's get back down before he starts calling us. And for Cran's sake doan' let him think you've got the wind-up about the mighty city of Bekla. You've got to learn to shrug-your shoulders and spit, banzi. Go on, do it now."

Smiling in spite of herself, Maia obeyed; whereupon Occula took her hand and ran with her down the slope.

Maia noticed, however, that she still kept her eyes averted from the opposite rise.