Fiction

$16.95

mcbooks

press

cross of

“One of our foremost writers of naval fiction.”

—Sunday Times

cr

os

“Kent doesn’t make it easy for his hero. But he does endow S s

St

S tGe

G o

e r

o g

r e

g

t o

him with the authenticity that makes these adventures the G f

closest thing to C.S. Forester still coming off the presses.” eo

—The New York Times Book Review rge

1813: American privateers prey on British ships in the wake of the War of 1812. Admiral Richard Bolitho returns A

to Halifax to defend crown property, fi ghting fruitless skirmishes in the cold, unforgiving waters off Nova Scotia. While Bolitho’s le

enemies in the Admiralty pull strings behind the scenes to bring xa

him down, his nephew Adam rises to the grueling challenges of nd

command.

e

ALEXANDER KENT is the pen name of British author Douglas r

Reeman. After serving in the Royal Navy during WWII, he turned K

to writing, publishing books under his own name and the Bolitho e

series under the Kent pseudonym. The popular Bolitho novels have n

been translated into nearly two dozen languages.

t

www.bolithomaritimeproductions.com

ISBN: 978-0-935526-92-9

5 1 6 9 5

McBooks Press

22

www.mcbooks.com

9 780935 526929

Alexande

n r

de Ken

K t

en

the Bolitho novels: 22

cross of

S t george

Selected Historical Fiction Published by McBooks Press BY ALEXANDER KENT

BY JULIAN STOCKWIN

BY JAMES DUFFY

The Complete

Mutiny

Sand of the Arena

Midshipman Bolitho

Quarterdeck

BY JOHN BIGGINS

Stand Into Danger

Tenacious

A Sailor of Austria

In Gallant Company

Command

The Emperor’s Coloured Coat

Sloop of War

BY JAN NEEDLE

The Two-Headed Eagle

To Glory We Steer

A Fine Boy for Killing

Tomorrow the World

Command a King’s Ship

The Wicked Trade

Passage to Mutiny

BY R.F. DELDERFIELD

The Spithead Nymph

With All Despatch

Too Few for Drums

Form Line of Battle!

BY DUDLEY POPE

Seven Men of Gascony

Enemy in Sight!

Ramage

BY JAMES L. NELSON

The Flag Captain

Ramage & The Drumbeat

The Only Life That

Signal–Close Action!

Ramage & The Freebooters

Mattered

The Inshore Squadron

Governor Ramage R.N.

A Tradition of Victory

Ramage’s Prize

BY C.N. PARKINSON

Success to the Brave

Ramage & The Guillotine

The Guernseyman

Colours Aloft!

Ramage’s Diamond

Devil to Pay

Honour This Day

Ramage’s Mutiny

The Fireship

The Only Victor

Ramage & The Rebels

Touch and Go

Beyond the Reef

The Ramage Touch

So Near So Far

The Darkening Sea

Ramage’s Signal

Dead Reckoning

For My Country’s Freedom

Ramage & The Renegades

The Life and Times of

Cross of St George

Ramage’s Devil

Horatio Hornblower

Sword of Honour

Ramage’s Trial

BY NICHOLAS NICASTRO

Second to None

Ramage’s Challenge

The Eighteenth Captain

Relentless Pursuit

Ramage at Trafalgar

Between Two Fires

Man of War

Ramage & The Saracens

Heart of Oak

Ramage & The Dido

BY DOUGLAS REEMAN

Badge of Glory

BY PHILIP MCCUTCHAN

BY FREDERICK MARRYAT

First to Land

Halfhyde at the Bight

Frank Mildmay or

The Horizon

of Benin

The Naval Officer

Dust on the Sea

Halfhyde’s Island

Mr Midshipman Easy

Knife Edge

Halfhyde and the

Newton Forster or

Guns of Arrest

The Merchant Service

Twelve Seconds to Live

Halfhyde to the Narrows

Snarleyyow or

Battlecruiser

Halfhyde for the Queen

The Dog Fiend

The White Guns

Halfhyde Ordered South

The Privateersman

A Prayer for the Ship

Halfhyde on Zanatu

For Valour

BY V.A. STUART

BY DAVID DONACHIE

BY DEWEY LAMBDIN

Victors and Lords

The French Admiral

The Sepoy Mutiny

The Devil’s Own Luck

The Gun Ketch

Massacre at Cawnpore

The Dying Trade

Jester’s Fortune

The Cannons of Lucknow

A Hanging Matter

The Heroic Garrison

An Element of Chance

What Lies Buried

The Scent of Betrayal

The Valiant Sailors

BY ALEXANDER FULLERTON

A Game of Bones

The Brave Captains

Storm Force to Narvik

Hazard’s Command

On a Making Tide

Last Lift from Crete

Hazard of Huntress

Tested by Fate

All the Drowning Seas

Hazard in Circassia

Breaking the Line

A Share of Honour

Victory at Sebastopol

The Torch Bearers

BY BROOS CAMPBELL

Guns to the Far East

The Gatecrashers

No Quarter

Escape from Hell

The War of Knives

Alexander Kent

Cross of St George

the Bolitho novels: 22

McBooks Press, Inc.

www.mcbooks.com

ITHACA, NY

Published by McBooks Press 2001

Copyright © 1996 by Bolitho Maritime Productions First published in the United Kingdom by William Heinemann Ltd. 1996

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. Requests for such permissions should be addressed to McBooks Press, Inc., ID Booth Building, 520 North Meadow St., Ithaca, NY 14850.

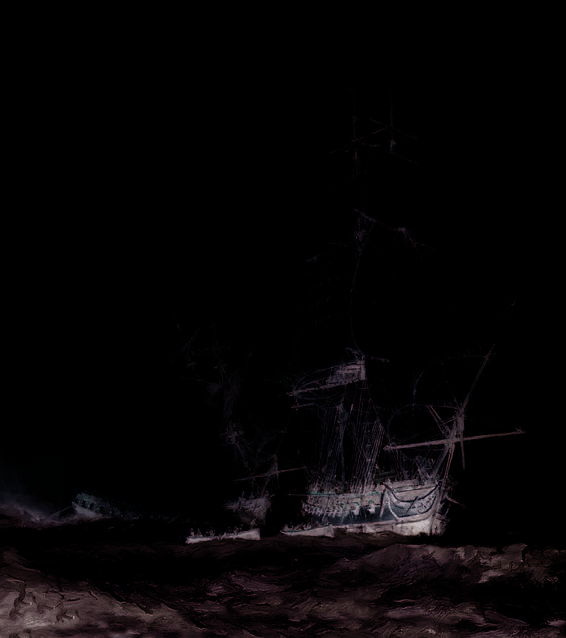

Cover painting by Geoffrey Huband.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kent, Alexander.

Cross of St George / by Alexander Kent.

p. cm. — (Richard Bolitho novels ; 22) ISBN 0-935526-92-7

1. Bolitho, Richard (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Napoleonic Wars, 1800‒1815 —Fiction 3. Great Britain, History, Naval—19th century—Fiction. I. Title

PR6061.E63 C76 2001

823/.914—dc21 01-030032

A

vAll McBooks Press publications can be ordered by calling toll-free 1-888-BOOKS11 (1-888-266-5711).

Please call to request a free catalog.

Visit the McBooks Press website at www.mcbooks.com.

Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6

For my Kim with love,

and with thanks for sharing

your Canada with me.

Wherever wood can swim, there I am sure to find this flag of England.

—NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

1 S word of honour

THE ROYAL DOCKYARD at Portsmouth, usually a place of noise and constant movement, was as quiet as the grave. It had been snowing steadily for two days, and the buildings, workshops, piles of timber and ships’ stores which made up the clutter in every big yard had become only meaningless shapes. And it was still snowing. Even the familiar smells had been overwhelmed by the white blanket: the sharp tang of paint and tar, hemp and new sawdust, like the sounds, seemed smothered and distorted. And, muffled by the snow, the echoing report of the court-martial gun had gone almost unnoticed.

Set apart from the other buildings, the port admiral’s house and offices were even more isolated than usual. From one of the tall windows, which overlooked a nearby dock, it was not even possible to see the water in the harbour.

Captain Adam Bolitho wiped the damp glass and stared down at a solitary Royal Marine, whose scarlet tunic was a stark contrast to the blinding whiteness of the backdrop. It was early afternoon; it could have been sunset. He saw his reflection in the window, and the light of the blazing log fire on the other side of the room, where his companion, a nervous lieutenant, sat perched on the edge of his chair with his hands held out to the flames. At any other time Adam Bolitho could have felt sorry for him. It was never an easy or a welcome duty to be the companion . . . his mouth tightened. The escort, for someone awaiting the convenience of a court martial. Even though everyone had assured him that the verdict would be unquestionably in his favour.

They had convened this morning in the spacious hall adjoining the admiral’s house, a place more usually the venue of 8

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

receptions than a courtroom where a man’s future, even his life, could be decided. Grotesquely, there had even been a few traces of the Christmas ball which had been held there recently. Adam stared at the snow. Now it was another year: January 3, 1813. After what he had endured, he might have imagined that he would have grasped at a new beginning like a drowning man seizing a lifeline. But he could not. All he loved and cared for lay in 1812, with so many broken memories. He sensed the lieutenant shifting in his chair, and was aware of movement elsewhere. The court was reassembling. After a damned good meal, he thought: obviously one of the reasons for holding the proceedings here, rather than force the court to endure the discomfort of a long pull in an open boat to the flagship, somewhere out there in the snow at Spithead.

He touched his side, where the iron splinter had smashed him down. He had believed he was dying: at times, he had even wanted to die. Weeks and months had passed, and yet it was hard to accept that it was less than seven months since he had been wounded, and his beloved Anemone had been surrendered to the enemy, overwhelmed by the massive artillery of the U.S.S. Unity.

Even now, the memories were blurred. The agony of the wound, the suffering of his spirit, unable to accept that he was a prisoner of war. Without a ship, without hope, someone who would soon be forgotten.

He felt little pain now; even one of the fleet surgeons had praised the skill of Unity’s French surgeon, and other doctors who had done what they could for him during his captivity.

He had escaped. Men he had barely known had risked everything to hasten his freedom, and some had died for it. And there were others, who could never be repaid for what they had done for him.

The lieutenant said hoarsely, “I think they’ve returned, sir.” CROSS OF S T GEORGE

9

Adam acknowledged it. The man was afraid. Of me? Of having become too intimate, if it goes against me?

His frigate, Anemone, had turned to face a vastly superior enemy, out-gunned and out-manned, with many of his company sent away as prize crews. He had not acted out of arrogance, or reckless pride, but to save the convoy of three heavily laden merchantmen he had been escorting to the Bermudas. Anemone’s challenge had given the convoy time to escape, to find safety when darkness came. He remembered Unity’s impressive commander, Nathan Beer, who had had him moved to his own quarters, and had come to visit him as he was treated by the surgeon. Even through the mists of agony and delirium, Adam had sensed the big American’s presence and concern. Beer had spoken to him more like a father to his son than like a fellow captain, and an enemy.

And now Beer was dead. Adam’s uncle, Sir Richard Bolitho, had met and engaged the Americans in a brief and bloody encounter, and it had been Bolitho’s turn to give comfort to his dying adversary. Bolitho believed they had been fated to meet: neither had been surprised by the conflict or its ferocity.

Adam had been given another frigate, Zest, whose captain had been killed while engaging an unknown vessel. He had been the only casualty, just as Adam had been the only survivor from Anemone apart from a twelve-year-old ship’s boy. The others had been killed, drowned, or taken prisoner.

The only verbal evidence submitted this morning had been his own. There had been one other source of information. When Unity had been captured and taken into Halifax, they had found the log which Nathan Beer had been keeping at the time of Anemone’s attack. The court had been as silent as the falling snow as the senior clerk read aloud Beer’s comments concerning the fierce engagement, and the explosion aboard Anemone which had 10

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

ended any hope of taking her as a prize. Beer had also written that he was abandoning his pursuit of the convoy due to the damage his enemy had inflicted. At the end of the report he had written, Like father, like son.

A few quick glances were exchanged in the court, nothing more. Most of those present were either unaware of Beer’s meaning, or unwilling to remark on anything that might prejudice the outcome.

But to Adam, it had been like hearing the big American’s voice in that hushed room. As if Beer was there, offering his tes-timony to an adversary’s courage and honour.

But for Beer’s log, there was little else to confirm what had truly happened. And if I were still a prisoner? Who would be able to help? I should be remembered only as the captain who struck his colours to the enemy. Badly wounded or not, the Articles of War left little room for leniency. You were guilty, unless proven without doubt to the contrary.

He was gripping his fingers together behind his back, so hard that the pain helped to steady him. I did not strike my colours. Then, or at any time.

Curiously enough, he knew that two of the captains who were sitting on the board had also been court-martialled. Perhaps they had been remembering, comparing. Thinking of how it might have been, if the point of the sword had been towards them . . .

He moved away from the window and paused by a tall mirror. Perhaps this was where officers examined their appearance, to ensure it would meet with the admiral’s approval. Or women

. . . He stared coldly at his reflection, holding back the memory.

But she was always there. Out of reach, as she had been when she was alive, but always there. He glanced at the bright gold epaulettes. The post-captain. How proud his uncle had been. Like everything else, his uniform was new; all his other possessions lay now in his chests on the seabed. Even the sword on the court-CROSS OF S T GEORGE

11

martial table was a borrowed one. He thought of the beautiful blade the City merchants had presented to him: they had owned the three ships he had saved, and were showing their gratitude.

He looked away from his reflection, his eyes angry. They could afford to be grateful. So many who had fought that day would never know about it.

He said quietly, “Your duty is all but done. I have been bad company, I fear.”

The lieutenant swallowed hard. “I am proud to have been with you, sir. My father served under your uncle, Sir Richard Bolitho.

Because of what he told me, I always wanted to enter the navy.” Despite the tension and unreality of the moment, Adam was strangely moved.

“Never lose it. Love, loyalty, call it what you will. It will sustain you.” He hesitated. “It must.” They both looked at the door as it opened carefully, and the Royal Marine captain in charge of the guard peered in at them.

He said, “They are waiting, Captain Bolitho.” He seemed about to add something, encouragement, hope, who could tell.

But the moment passed. He banged his heels together smartly and marched out into the corridor.

When he glanced back, Adam saw the lieutenant staring after him. Trying to fix the moment in his mind, perhaps to tell his father.

He almost smiled. He had forgotten to ask him his name.

The great room was full to capacity, although who they were and what they sought here was beyond understanding. But then, he thought, there was always a good crowd for a public hanging, too.

Adam was very aware of the distance, the click of the marine captain’s heels behind him. Once he slipped. There was still powdered chalk on the polished floor, another reminder of the Christmas ball.

12

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

As he came around the last line of seated spectators to face the officers of the board, he saw his borrowed sword on the table; its hilt was toward him. He was shocked, not because he knew the verdict was a just one, but because he felt nothing. Nothing.

As if he, like all these others, was a mere onlooker.

The president of the court, a rear-admiral, regarded him gravely.

“Captain Adam Bolitho, the verdict of this Court is that you are honourably acquitted.” He smiled briefly. “You may be seated.” Adam shook his head. “No, sir. I prefer not.”

“Very well.” The rear-admiral opened his brief. “The Court holds that Captain Adam Bolitho not only acquitted himself of his duty in the best tradition of the Royal Navy, but in the execution of such duty has done infinite credit to himself by a very obstinate defence against a most superior force. By placing his ship between the enemy and the vessels charged to his protection, he showed both courage and initiative of the highest order.” He raised his eyes. “But for those qualities, it would seem unlikely that you would have succeeded, particularly in view of the fact that you had no knowledge of the declaration of war. Otherwise . . .” The word hung in the air. He did not need to explain further what the outcome of the court martial would have been.

All the members of the court stood up. Some were smiling broadly, obviously relieved that it was all over.

The rear-admiral said, “Retrieve your sword, Captain Bolitho.” He attempted to lighten it. “I would have thought you might be wearing that fine sword of honour I have been hearing about, eh?” Adam slid the borrowed sword into its scabbard. Leave now.

Say nothing. But he looked at the rear-admiral and the eight captains who were his court and said, “George Starr was my coxswain, sir. With his own hand he lit charges which speeded the end of my ship. But for him, Anemone would be serving in the United States navy.”

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

13

The rear-admiral nodded, his smile fading. “I know that. I read it in your report.”

“He was a good and honest man who served me, and his country, well.” He was aware of the sudden silence, broken only by the creak of chairs as those at the back of the great room leaned forward to hear his quiet, unemotional voice. “But they hanged him for his loyalty, as if he were a common felon.” He looked at the faces across the table, without seeing them.

His outward composure was a lie, and he knew he would break down if he persisted. “I sold the sword of honour to a collector who values such things.” He heard the murmurs of surprise behind his back. “As for the money, I gave it to George Starr’s widow. It is all she will receive, I imagine.” He bowed stiffly and turned away from the table, walking between the ranks of chairs with his hand to his side as if he expected to feel the old torment. He did not even see the expressions, sympathy, understanding, and perhaps shame: he saw only the door, which was already being opened by a white-gloved marine. His own marines and seamen had died that day, a debt no sword of honour could ever repay.

There were a few people in the outer lobby. Beyond them, he saw the falling snow, so clean after what he had attempted to describe.

One, a civilian, stepped forward and held out his hand. His face seemed vaguely familiar, yet Adam knew they had never met.

The man hesitated. “I am so sorry, Captain Bolitho. I should not detain you further after what you have just experienced.” He glanced across the room where a woman sat, gazing at them intently. “My wife, sir.”

Adam wanted to leave. Very soon the others would be milling around him, congratulating him, praising him for what he had done, when earlier they would have watched him facing the point 14

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

of the sword with equal interest. But something held him. As if someone had spoken aloud.

“If I can be of service, sir?”

The man was well over sixty years old, but there was an erect-ness, a pride in his bearing as he explained, “My name is Hudson, Charles Hudson. You see . . .” He fell silent as Adam stared at him, his composure gone.

He said, “Richard Hudson, my first lieutenant in Anemone.” He tried to clear his mind. Hudson, who had slashed down the ensign with his hanger while he himself lay wounded and unable to move. Again, it was like being an onlooker, hearing others speak . I ordered you to fight the ship! Each despairing gasp wrenching at his wound like a branding iron. And all the while Anemone was dying beneath them, even as the enemy surged alongside.

And Hudson’s last words before Adam was lowered into a boat.

If we ever meet again . . .

Adam could still hear his own answer. As God is my witness, I will kill you, damn your eyes!

“We had only one letter from him.” Hudson glanced again at his wife and Adam saw her nod, helping him. She looked frail, unwell. It had cost them dearly to come here.

He said, “How is he?”

Charles Hudson did not seem to hear. “My brother was a vice-admiral. He used his influence to have Richard appointed to your ship. When he wrote, he always spoke of you so warmly . . . he was so proud to be serving with you. When I heard about your court martial, as they dare to call it, we had to come. To see you, to thank you for what you did for Richard. He was our only son.” Adam tensed. Was. “What happened?”

“In his letter he said he wanted to find you. To explain . . .

something.” He dropped his head. “He was shot, attempting to escape. He was killed.”

Adam felt the room sway, like the deck of a ship. All that CROSS OF S T GEORGE

15

time, the pain and the despair, the hatred because of what had happened; and he had thought only of himself.

He said, “I shall tell my uncle when I see him. He was known to your son.” Then he took the man’s arm and led him towards his wife. “There was nothing for Richard to explain. Now he is at peace, he will know that.”

Hudson’s mother was on her feet, holding out her hand to him. Adam stooped, and kissed her cheek. It was like ice.

“Thank you.” He looked at each of them. “Your loss is my loss also.”

He glanced round as a lieutenant coughed politely, and murmured, “The port admiral wishes to see you, sir.”

“Can’t it wait?”

The lieutenant licked his lips. “I was told that it was important, sir. To you.”

Adam turned to say goodbye, but they had gone, as quietly and patiently as they had waited.

He felt his cheek. Her tears, or were they his own?

Then he followed the lieutenant, past people who smiled and reached out to touch his arm as he passed. He saw none of them.

He heard nothing but his own anger. I ordered you to fight the ship. It was something he would never forget.

Lady Catherine Somervell walked softly toward the window, her bare feet soundless as she glanced back at the bed. She listened to his breathing. Quiet now: he was asleep, after the restlessness he had tried to conceal from her.

She realized that the night was quite still, and there was a hint of moonlight for the first time. She groped for a heavy silk shawl but paused again as he stirred on the bed, one arm resting on the sheet where she had been lying.

She looked out at the ragged clouds, moving more slowly, allowing the moon to touch the street, which shone still from the 16

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

night’s downpour. Across the road, which was all that separated this row of houses from the Thames, she could just discern the restless water. Like black glass in the moonlight. Even the river seemed quiet, but this was London: within hours this same road would be busy with traders on their way to market, and people setting up their stalls, rain or no rain.

She shivered, despite the thick shawl, and wondered what daylight would bring.

Little more than a month had passed since Richard Bolitho had returned home, and the guns of St Mawes battery had thundered out their salute to Falmouth’s most famous son. An admiral of England, a hero and an inspiration to the men who followed his flag.

She wanted to go to him now. Not to the public figure, but to the man, her man, whom she loved more than life itself.

This time she could not help him. His nephew had been ordered to face a court martial, the direct consequence of losing Anemone to the enemy. Richard had told her that the verdict would vindicate Adam, but she knew him so well that he could not conceal his anxiety and his doubt. His business at the Admiralty had prevented him from being at Portsmouth where the court was convened; she also knew that Adam had insisted upon facing the court alone, and unaided. He knew too well how Bolitho hated favouritism, and the manipulative use of outside influence. She smiled sadly. They were so alike, more like brothers than anything else.

Vice-Admiral Graham Bethune had assured Richard that he would inform him immediately he heard anything: the fast telegraph from Portsmouth to London could bring a despatch to the Admiralty in less than half an hour. The court had been convened yesterday morning, and as yet there had been no word. Nothing.

Had they been in Falmouth she might have distracted him, involved him in the estate’s affairs, in which she had taken such CROSS OF S T GEORGE

17

an interest during his long absences at sea. But their presence had been required in London. The war with the United States, which had erupted last year, was believed to be at a turning point, and Bolitho had been summoned to the Admiralty to settle doubts, or perhaps inspire confidence. She felt the old bitterness. Was there nobody else they could send? Her man had done enough, and had too often paid the price.

She must confront it: they would soon be parted again. If only they could get back to Cornwall . . . It might take all of a week, with the roads in their present state. She thought of their room at the old grey house below Pendennis Castle, the windows that faced the sea. The rides, and the walks they enjoyed so much . . .

She shivered again, but not from cold. What ghosts would wait for them when they took that particular walk, where the despairing Zenoria had flung herself to her death?

So many memories. And the other side of the coin: the envy and the gossip, even the hatred, which was more subtly revealed.

Scandal, which they had both endured and surmounted. She looked at the dark hair on the pillow. No wonder they love you.

Dearest of men.

She heard the sound of iron wheels, the first sign of life in the street. Going to fetch fish from the market, no doubt. Peace or war, the fish were always there on time.

She slipped her hand inside her gown, her fingers cold around her breast. As he had held her, and would hold her again. But not this night. They had lain without passion in one another’s arms, and she had shared his anxiety.

She had felt the cruel scar on his shoulder, where a musket ball had cut him down. So many years ago, when her husband, Luis, had been killed by Barbary pirates aboard the Navarra. She had cursed Richard on that day, blaming him for what had happened. And then, after he had been wounded, he had been plagued by the return of an old fever, which had almost claimed his life.

18

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

She had climbed into the cot with him, naked, to comfort him and hold the icy grip of the fever at bay. She could smile at the memory now. He had known nothing about it. So many years, and yet it could have been yesterday . . .

He had changed her life, and she knew she had changed his.

Something that went far beyond his demanding world of duty and danger, something only they shared, which made people turn and look at them when they were together. So many unspoken questions; something others could never understand.

She touched her skin again. Will he always find me beautiful when he returns from another campaign, another country? I would die for him.

She reached out to close the curtains, and then stood quite still, as if she were held by something. She shook her head, angry with herself. It was nothing. She wiped the window pane with her shawl and stared at the street below, The Walk, as it was called locally. A few patches of moonlight revealed the trees, black and bare of leaves, like charred bones. Then she heard it: the rattle of wheels on the cobbles, the gentle step of a solitary horse.

Moving slowly, as if uncertain of the way. A senior officer returning to his quarters at the barracks nearby after a night of cards, or, more likely, with his mistress.

She watched, and eventually a small carriage moved across a bar of moonlight: even the horse looked silver in the cold glow.

Two carriage lamps were burning like bright little eyes, as if they and not the horse were finding the way.

She sighed. Probably someone who had taken too much to drink, and would be overcharged by the driver for his folly.

Her hand was still beneath her breast, and she could feel her heart beating with sudden disbelief. The carriage was veering across the road towards this house.

She stared down, barely able to breathe as the door opened and a white leg paused uncertainly on the step. The coachman CROSS OF S T GEORGE

19

was gesturing with his whip. It was like a mime. The passenger stepped down soundlessly onto the pavement. Even the gold buttons on his coat looked like pieces of silver.

And then Richard was beside her, gripping her waist, and she imagined she must have called out, although she knew she had not.

He looked down at the road. The sea officer was peering at the houses, while the coachman waited.

“From the Admiralty?” She turned toward him.

“Not at this hour, Kate.” He seemed to come to a decision.

“I’ll go down. It must be a mistake.” Catherine looked down again, but the figure by the carriage had vanished. The bang on the front door shattered the stillness like a pistol shot. She did not care. She had to be with him, now, of all times.

She waited on the stairs, the chill air exploring her legs, as Bolitho opened the door, staring at the familiar uniform, and then at the face.

Then he exclaimed, “Catherine, it’s George Avery.” The housekeeper was here now, muttering to herself and bringing fresh candles, obviously disapproving of such goings-on.

Catherine said, “Fetch something hot, Mrs Tate. Some cognac, too.”

George Avery, Bolitho’s flag lieutenant, was sitting down as if gathering himself. Then he said, “Honourably acquitted, Sir Richard.” He saw Catherine for the first time, and made to rise.

“My lady.”

She came down, and put her hand on his shoulder. “Tell us.

I can hardly believe it.”

Avery gazed at his filthy boots. “I was there, Sir Richard. I thought it only right. I know what it is to face the possibility of disgrace and ruin at a court martial.” He repeated, “I thought it was only right. There was heavy snow on the south coast. The 20

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

telegraph towers were hidden from one another. It might have taken another day for the news to reach you.”

“But you came?” Catherine saw Bolitho grip his arm.

Surprisingly, Avery grinned. “I rode most of the way. I forget how many times I changed horses. Eventually I fell in with the fellow outside, otherwise I doubt I’d have found the place.” He took the glass of cognac, and his hand shook uncontrollably.

“Probably cost me a year’s pay, and I don’t think I’ll be able to sit down comfortably for a month!”

Bolitho walked to a window. Honourably acquitted. As it should be. But things did not always end as they should.

Avery finished the cognac and did not protest when Catherine refilled his glass. “Forced a few coaches and carts off the road—” He saw Bolitho’s expression and added gently, “I was not in court, Sir Richard, but he knew I was there. Your nephew was going to see the port admiral. Someone said that he has an extended leave of absence. That is all the information I have.” Bolitho looked at Catherine, and smiled. “Seventy miles on dark and treacherous roads. What sort of man would do that?” She removed the glass from Avery’s nerveless fingers as he lolled against the cushions, and was asleep.

She replied quietly, “Your sort of man, Richard. Are you at peace now?”

When they reached the bedroom they could see the river quite clearly, and there were indeed people already moving along the road. It was unlikely that anyone had noticed the sudden arrival of the carriage, or the tall sea officer banging on the door. If they had, they would think little of it. This was Chelsea, a place that minded its own business more than most.

Together they looked at the sky. It would soon be daylight, another grey January morning. But this time, with such a difference.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

21

She held his arm around her waist and said, “Perhaps your next visit to the Admiralty will be the last for a while.” He felt her hair against his face. Her warmth. How they belonged.

“And then, Kate?”

“Take me home, Richard. No matter how long we must travel.” He guided her to the bed, and she laughed as the first dogs began to bark outside.

“Then you can love me. In our home.” Vice-Admiral Graham Bethune was already on his feet when Bolitho was ushered into his spacious rooms at the Admiralty, and his smile was warm and genuine.

“We are both abroad early today, Sir Richard.” His face fell slightly. “Although I fear I have not yet had news of your nephew, Captain Bolitho. The telegraph, excellent though it may be in many ways, is no match for our English weather!” Bolitho sat down as a servant removed his hat and cloak. He had walked only a few paces from the carriage, but the cloak was soaked with rain.

He smiled. “Adam was honourably acquitted.” Bethune’s astonishment was a pleasure to see. They had met several times since Bolitho’s arrival in London, but he was still surprised that Bethune’s new authority had not changed him in some way. In appearance, he had matured a good deal since his days as a midshipman in Bolitho’s first command, the little sloop-of-war Sparrow. Gone was the round-faced youth, his complexion a mass of dark freckles; here was a keen-eyed, confident flag officer who would turn any woman’s head at Court, or at the many elegant functions it was now his duty to attend. Bolitho recalled Catherine’s initial resentment when he had told her that Bethune was not only a younger man, but also his junior in rank. She was 22

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

not the only one who was baffled by the ways of Admiralty.

He said, “My flag lieutenant, Avery, rode all the way from Portsmouth this morning to tell me.” Bethune nodded, his mind busy on another course. “George Avery, yes. Sir Paul Sillitoe’s nephew.” Again the boyish smile. “I am sorry. Baron Sillitoe of Chiswick, as he is now. But I am glad to know it. It must have been hard for your nephew, losing ship and liberty at one blow. And yet you appointed him to command Zest at the final encounter with Commodore Beer’s ships. Remarkable.” He walked to a table. “I sent my own report, needless to say. One has little confidence in courts martial, as we have seen many times for ourselves.”

Bolitho relaxed slightly. So Bethune had found the time to put pen to paper on Adam’s behalf. He could not imagine either of his predecessors, Godschale, or particularly Hamett-Parker, even raising a finger.

Bethune glanced at the ornate clock beside a painting of a frigate in action. Bolitho knew it was his own command, when Bethune had confronted two large Spanish frigates and, despite the odds, had run one ashore and captured the other. A good beginning, which had done his career no harm at all.

“We shall take refreshment shortly.” He coughed. “Lord Sillitoe is coming today, and I am hoping we shall learn more of the Prince Regent’s views on the American conflict.” He hesitated, momentarily unsure of himself. “One thing is almost certain. You will be required to return to that campaign. What is it now, a bare four months since you engaged and defeated Commodore Beer’s ships? But your opinions and your experience have been invaluable. I know it is asking too much of you.” Bolitho realized that he was touching his left eye. Perhaps Bethune had noticed, or maybe word of the injury and the impos-sibility of recovery had finally reached this illustrious office.

He answered, “I had expected it.”

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

23

Bethune observed him thoughtfully. “I had the great pleasure of meeting Lady Somervell, Sir Richard. I know what this parting will mean to you.”

Bolitho said, “I know you met her. She told me. There are no secrets between us, and never will be.” Catherine had also met Bethune’s wife, at a reception at Sillitoe’s house by the river. She had said nothing about her, but she would, when she judged that the moment was right. Perhaps Bethune had an eye for the ladies?

A mistress, maybe.

He said, “You and I are friends, is that not so?” Bethune nodded, not understanding. “A small word, for what it truly means.”

“I agree.” He smiled. “Call me Richard. I feel that rank, and the past, stand in the way.”

Bethune strode to his chair, and they shook hands. “This is a far better day than I dared hope.” He grinned, and looked very young. “Richard.” Another glance at the clock. “There is another matter, which I would like to discuss with you before Lord Sillitoe arrives.” He watched him for a few seconds. “You will soon know. Rear-Admiral Valentine Keen is being appointed to a new command, which will be based in Halifax, Nova Scotia.”

“I had heard as much.” Full circle, he thought. Halifax, where he had left his flagship, Indomitable, upon his recall to England.

Was it really so short a time ago? With her had been their two equally powerful prizes, Beer’s USS Unity and the Baltimore, which together carried as much artillery as a ship of the line. Fate had decided the final meeting; determination and a bloody need to win had decided the outcome. After all the years he had been at sea, pictures could still stand out as starkly as ever. Allday’s grief, alone among all the gasping survivors as he had carried his dead son, and had lowered him into the sea. And the dying Nathan Beer, their formidable adversary, with Bolitho’s hand in his, each understanding that the meeting and its consequences 24

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

had been inevitable. They had covered Beer with the American flag, and Bolitho had sent his sword to his widow in Newburyport. A place well known to men-of-war and privateers; where his own brother Hugh had once found refuge, if not peace.

Bethune said, “Rear-Admiral Keen will hoist his flag in the frigate Valkyrie. Her captain, Peter Dawes, who was your second-in-command, stands to accept promotion and is eager to take another appointment.” He paused discreetly. “His father, the admiral, suggested that the present was as good a time as any.” So Keen was going back to war, still in mourning for Zenoria. It was what he needed, or imagined he needed. Bolitho himself had known the haunting demands of grief, until he had found Catherine again.

“A new flag captain, then?” Even as he spoke, he knew who it would be. “Adam?”

Bethune did not answer directly. “You gave Zest to him out of necessity.”

“He was the best frigate captain I had.” Bethune continued, “When Zest returned to Portsmouth she was found to be in a sorry state of repair. Over four years in commission, and after two captains—three, if you count your nephew—and several sea-fights, which left her with deep and lasting damage, and without proper facilities for complete repair

. . . the last battle with Unity was the final blow. The port admiral was instructed to explain all this to your nephew after the court’s verdict was delivered. It will take months before Zest is ready for service again. Even then . . .” After the court’s verdict. Bolitho wondered if Bethune shared the true meaning. Had the sword been pointing at Adam, he would have been fortunate to have remained in the navy, even with a ship as worn and weakened as Zest.

Bethune was not unaware of it. “By which time, this war will probably be over, and your nephew, like so many others, could be CROSS OF S T GEORGE

25

rejected by the one calling he loves.” He unfolded a map without appearing to see it. “Rear-Admiral Keen and Captain Bolitho have always been on good terms, both under your command and elsewhere. It would seem a satisfactory solution.” Bolitho tried not to remember Adam’s face as he had seen it that day in Indomitable, when he had given him the news of Zenoria’s death. It had been like watching his heart break into pieces. How could Adam agree? Knowing that each day he would be serving alongside and under the orders of the man who had been Zenoria’s husband. The girl with moonlit eyes. She had married Keen out of gratitude. Adam had loved her . . . loved her.

But Adam, too, might be grateful for an escape provided by Keen.

A ship at sea, not an undermanned hulk suffering all the indignities of a naval dockyard. How could it work? How might it end?

He loved Adam like a son, always had loved him, ever since the youth had walked from Penzance to present himself to him after his mother’s death. Adam had confessed his affair with Zenoria: he felt that he should have known. Catherine had seen it much earlier in Adam’s face, on the day Zenoria had married Keen in the mermaid’s church at Zennor.

Madness even to think about it. Keen was going to his first truly responsible command as a flag officer. Nothing in the past could change that.

He asked, “You really believe that the war will soon end?” Bethune showed no surprise at this change of tack. “Napoleon’s armies are in retreat on every front. The Americans know this.

Without France as an ally, they will lose their last chance of dominating North America. We shall be able to release more and more ships to harass their convoys and forestall large troop movements by sea. Last September you proved, if proof were needed, that a well-placed force of powerful frigates was far more use than sixty ships of the line.” He smiled. “I can still recall their faces in the other room when you told Their Lordships that the 26

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

line of battle was finished. Blasphemy, some thought, and unfortunately there are still many you have yet to convince.” Bolitho saw him look at the clock yet again. Sillitoe was late.

He knew the extent of his own influence and accepted it, knew too that people feared him. Bolitho suspected it pleased him.

Bethune was saying, “All these years, Richard, a lifetime for some. Twenty years of almost unbroken war with the French, and even before that, when we were in Sparrow during the American rebellion, we were fighting France as well.”

“We were all very young then, Graham. But I can understand why ordinary men and women have lost faith in victory, even now, when it is within our grasp.”

“But you never doubted it.”

Bolitho heard voices in the corridor. “I never doubted we would win, eventually. Victory? That is something else.” A servant opened the fine double doors and Sillitoe came unhurriedly into the room.

Catherine had described the portrait of Sillitoe’s father, which she had seen at the reception in his house. Valentine Keen had been her escort on that occasion: that would have set a few tongues wagging. But as he stood there now, in slate-grey broadcloth and gleaming white silk stock, Bolitho could compare the faces as if he had been there with her. Sillitoe’s father had been a slaver, “a black ivory captain,” he had called him. Baron Sillitoe of Chiswick had come far, and since the King had been declared insane his position as personal adviser to the Prince Regent had strengthened until there was very little in the political affairs of the nation he could not manipulate or direct.

He gave a curt bow. “You look very well and refreshed, Sir Richard. I was pleased to hear of your nephew’s exoneration.” Obviously, news travelled faster among Sillitoe’s spies than in the corridors of Admiralty.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

27

Sillitoe smiled, his hooded eyes, as always, concealing his thoughts.

“He is too good a captain to waste. I trust he will accept Rear-Admiral Keen’s invitation. I think he should. I believe he will.” Bethune rang for the servant. “You may bring refreshments, Tolan.” It gave him time to recover from his shock that Sillitoe’s network was more efficient than his own.

Sillitoe turned smoothly to Bolitho.

“And how is Lady Catherine? Well, I trust, and no doubt pleased to be back in town?”

Pointless to explain that Catherine wanted only to return to a quieter life in Falmouth. But one could not be certain of this man.

He who seemed to know everything probably knew that, too.

“She is happy, my lord.” He thought of her in the early hours of the morning when Avery had arrived. Happy? Yes, but concealing at the same time, and not always successfully, the deeper pain of their inevitable separation. Before Catherine, life had been very different. He had always accepted that his duty lay where his orders directed. It had to be. But his love he would leave behind, wherever she was.

Sillitoe leaned over the map. “Crucial times, gentlemen. You will have to return to Halifax, Sir Richard—you are the only one familiar with all the pieces of the puzzle. The Prince Regent was most impressed with your report and the vessels you require.” He smiled dryly. “Even the expense did not deter him. For more than a moment, that is.”

Bethune said, “The First Lord has agreed that orders will be presented within the week.” He glanced meaningfully at Bolitho.

“After that, Rear-Admiral Keen can take passage in the first available frigate, no matter who he selects as flag captain.” Sillitoe walked to a window. “Halifax. A cheerless place at this time of the year, I’m told. Arrangements can be made for you to 28

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

follow, Sir Richard.” He did not turn from the window. “Perhaps the end of next month—will that suit?” Bolitho knew that Sillitoe never made idle remarks. Was he considering Catherine at last? How she would come to terms with it. Cruel; unfair; too demanding. He could almost hear her saying it. Separation and loneliness. Less than two months, then, allowing for the uncomfortable journey to Cornwall. They must not waste a minute. Together.

He replied, “You will find me ready, my lord.” Sillitoe took a glass from the servant. “Good.” His hooded eyes gave nothing away. “Excellent.” He could have been describing the wine. “A sentiment, Sir Richard. To your Happy Few!” So he even knew about that.

Bolitho scarcely noticed. In his mind, he saw only her, the dark eyes defiant, but protective.

Don’ t leave me.

2 for the L ove of a lady

BRYAN FERGUSON, the one-armed steward of the Bolitho estate, opened his tobacco jar and paused before filling his pipe. He had once believed that even the simplest task would be beyond him forever: fastening a button, shaving, eating a meal, let alone filling a pipe.

If he stopped to consider it, he was a contented man, grateful even, despite his disability. He was steward to Sir Richard Bolitho and had this, his own house near the stables. One of the smaller rooms at the rear of the house was used as his estate office, not that there was much to do at this time of the year. But the rain had stopped, and they had been spared the snow that one of the post-boys had mentioned.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

29

He glanced around the kitchen, the very centre of things in the world he shared with Grace, his wife, who was the Bolitho housekeeper. On every hand were signs of her skills, preserves, all carefully labelled and sealed with wax, dried fruit, and at the other end of the room hanging flitches of smoked bacon. The smell could still make his mouth water. But it was no use. His mind was distracted from these gentle pleasures. He was too anxious on behalf of his closest and oldest friend, John Allday.

He looked now at the tankard of rum on the scrubbed table.

Untouched.

He said, “Come along, John, have your wet. It’s just what you need on a cold January day.”

Allday remained by the window, his troubled thoughts like a yoke on his broad shoulders.

He said at length, “I should have gone to London with him.

Where I belong, see?”

So that was it. “My God, John, you’ve not been home a dog-watch and you’re fretting about Sir Richard going to London without you! You’ve got Unis now, a baby girl too, and the snuggest little inn this side of the Helford River. You should be enjoying it.”

Allday turned and looked at him. “I knows it, Bryan. Course I do.”

Ferguson tamped home the tobacco, deeply troubled. It was even worse with Allday than the last time. He looked over at his friend, seeing the harsh lines at the corners of his mouth, caused, he thought, by the pain in his chest where a Spanish sword had struck him down. The thick, shaggy hair was patched with grey.

But his eyes were as clear as ever.

Ferguson waited for him to sit down and put his big hands around the particular pewter tankard they kept for him. Strong, scarred hands; the ignorant might think them awkward and clumsy. But Ferguson had seen them working with razor-edged 30

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

knives and tools to fashion some of the most intricate ship models he had ever known. The same hands had held his child, Kate, with the gentleness of a nursemaid.

Allday asked, “When do you reckon they’ll be back, Bryan?” Ferguson passed him the lighted taper and watched him hold it to his long clay; the smoke floated toward the chimney, and the cat lying on the hearth asleep.

“One of the squire’s keepers came by and he said the roads are better than last week. Slow going for a coach and four, let alone the mail.” It was not doing any good. He said, “I was thinking, John. It’ll be thirty-one years this April since the Battle of the Saintes. It hardly seems possible, does it?” Allday shrugged. “I’m surprised you can remember it.” Ferguson glanced down at his empty sleeve. “Not a thing I could easily forget.”

Allday reached across the table and touched his arm. “Sorry, Bryan. That was not intended.”

Ferguson smiled, and Allday took a swallow of rum. “It means that I’ll be fifty-three this year.” He saw Allday’s sudden discomfort. “Well, I’ve a piece of paper to prove it.” Then he asked quietly, “How old does that make you? About the same, eh?” He knew Allday was older; he had already served at sea when they had been taken together by the press-gang on Pendower Beach.

Allday eyed him warily. “Aye, something like that.” He looked at the fire, his weathered features suddenly despairing. “I’m his cox’n, y’see. I belongs with him.” Ferguson took the stone jug and poured another generous measure. “I know you do, John. Everyone does.” He was reminded suddenly of his cramped estate office, which he had left only an hour ago when Allday had arrived unexpectedly in a carrier’s cart.

Despite the fusty ledgers, and the dampness of winter, it was as if she had been there just ahead of him. Lady Catherine had not been in his office since before Christmas, when she had left for CROSS OF S T GEORGE

31

London with the admiral, and yet her perfume was still there.

Like jasmine. The old house was used to the comings and goings of Bolithos down over the years, he thought, and sooner or later one of them failed to return. The house accepted it: it waited, with all its dark portraits of dead Bolithos. Waited . . . But when Lady Catherine was away, it was different. An empty place.

He said, “Lady Catherine perhaps most of all.” Something in his voice made Allday turn to look at him.

“You too, eh, Bryan?”

Ferguson said, “I’ve never known such a woman. I was with her when they found that girl.” He stared at his pipe. “All broken up, she was, but her ladyship held her like a child. I shall never forget . . . I know you’re all aback at the thought that maybe you’re getting old, John, too old for the hard life of a fighting Jack. It’s my guess that Sir Richard fears it, too. But why am I telling you this? You know him better than anybody, man!” Allday smiled, for the first time. “I was that glad about Cap’n Adam keeping out of trouble at the court martial. That’ll be one thing off Sir Richard’s mind.”

Ferguson grunted, smoking. A revenue cutter had slipped into Falmouth, and had brought the news with some despatches.

Allday said bluntly, “You knew about him and that girl, Zenoria?”

“Guessed. It goes no further. Even Grace doesn’t suspect.” Allday blew out the taper. Grace was a wonderful wife to Bryan, and had saved him after he had returned home with an arm missing. But she did enjoy a good gossip. Lucky that Bryan understood her so well.

He said, “I love my Unis more than I can say. But I’d not leave Sir Richard. Not now that it’s nearly all over.” The door opened and Grace Ferguson came into the kitchen.

“Just like two old women, you are! What about my soup?” But she looked at them fondly. “I’ve just done something about they 32

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

fires. That new girl Mary’s willing enough, but she’s got the memory of a squirrel!”

Ferguson exclaimed, “Fires, Grace? Aren’t you being a bit hasty?” But his mind was not on what he was saying. He was still turning over Allday’s words. I’d not leave Sir Richard. Not now that it’s nearly all over. He tried to brush it aside, but it would not go.

What had he meant? When the war finally ended, and men paused to count the cost? Or did he fear for Sir Richard? That was nothing new. Ferguson had even heard Bolitho liken them both to a faithful dog and its master. Each fearful of leaving the other behind.

Grace looked keenly at him. “What is it, my dear?” He shook his head. “Nothing.”

Allday darted a glance between them. Although separated for long periods when he was at sea, he had no closer friends.

He said, “He thinks I’m getting old, ready to be broken up like some rotten hulk!”

She laid one hand on his thick wrist. “That’s foolish talk, you with a fine wife and a bonny baby. Old indeed!” But the smile did not touch her eyes. She knew both of them too well, and could guess what had happened.

The door opened again, and this time it was Matthew, the coachman. Like Allday, he had protested against remaining in Falmouth and entrusting Bolitho and Catherine to a common mail coach.

Ferguson was glad of the interruption. “What’s amiss, Matthew?”

Matthew grinned.

“Just heard the coach horn. Sounded it, like that other time when he was coming home!”

Ferguson said briskly, “Drive down and fetch them from the square,” but Matthew had already gone. He had been the first to know, just as he had been the first to recognize the St Mawes CROSS OF S T GEORGE

33

salute when Bolitho had returned to Falmouth a little over a month ago.

He paused to kiss his wife on the cheek.

“What was that for?”

Ferguson glanced at Allday. They were coming home. He smiled.

“For making up the fires for them.” But he could not repress it.

“For so many things, Grace.” He reached for his coat. “You can stop for a meal, John?”

But Allday was preparing to leave. “They’ll not want a crowd when they gets here.” He was suddenly serious. “But when he wants me, I’ll be ready. That’s it an’ all about it.” The door closed, and they looked at one another.

She said, “Taking it badly.”

Ferguson thought of the smell of jasmine. “So will she.” The smart carriage with the Bolitho crest on the door clattered away across the stableyard, the wheels striking sparks from the cobbles. For several days Matthew had been anticipating this, backing the horses into position at the time when the coach from Truro could be expected to arrive outside the King’s Head in Falmouth. Ferguson paused by the door. “Fetch some of that wine they favour, Grace.”

She watched him, remembering, as if it were yesterday, when they had snatched him away in the King’s ship. Bolitho’s ship.

And the crippled man who had returned to her. She had never put it into words before. The man I love.

She smiled. “Champagne. I don’t know what they see in it!” Now that it’s all nearly over. He might have told her what Allday had said, but she had gone, and he was glad that it would remain a secret between them.

Then he walked out into the cold, damp air and could smell the sea. Coming home. It was suddenly important that there should be no fuss: Allday had understood, even though he was bursting to know what was going to happen. It must be as if 34

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

they had only been from Falmouth for a single day.

He looked over at the end stall and saw the big mare Tamara throwing her head up and down, the white flash on her forehead very clear in the dull light.

There could be no more doubt. Ferguson walked over and rubbed her muzzle.

“She’s back, my lass. And none too soon.” Half an hour later the carriage rattled into the drive. The hero and his mistress who had scandalized the country, defying both hypocrisy and convention, were home.

Lieutenant George Avery regarded himself critically in the tailor’s mirror, as he might examine a stranger. He knew very little of London, and on previous visits he had usually been on some mission to the Admiralty. The tailor’s establishment was in Jermyn Street, a bustling place of shops and elegant houses, and the air, which seemed unclean after the sea, was alive with the din of carriages and hooves.

He must have walked for miles, something he always enjoyed after the restrictions of a crowded man-of-war. He smiled at his reflection; he was quite tired, unaccustomed to so much exercise.

It was strange to have money to spend, something new to him.

This was prize-money, earned over ten years ago when he had been second-in-command of the schooner Jolie, herself a French prize. He had all but forgotten about it; it had seemed unimportant in the light of his subsequent misfortunes. He had been wounded when Jolie was overwhelmed by a French corvette, then held as a prisoner of war in France; he had been exchanged during the brief Peace of Amiens only to face a court martial, and to receive a reprimand for losing his ship, even though he had been too badly injured to prevent others from hauling down her colours. At Adam Bolitho’s court martial he had relived every moment of his own disgrace.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

35

He thought of the house in Chelsea, where he was still staying, and wondered if Bolitho and Catherine had reached Cornwall yet. It was difficult to accept, let alone take for granted, that they had left him to use the house as he chose. But he would have to go to Falmouth soon himself, to be with the others when Sir Richard received his final instructions. His little crew, as he called them. Avery thought it was dangerously close to being a family.

Arthur Crowe, the tailor, peered up to him. “Is everything satisfactory, sir? I shall have the other garments sent to you immediately they are ready.” Polite, almost humble. Rather different from their first meeting. Crowe had seemed about to offer some critical comment on Avery’s uniform, which had been made by the Falmouth tailor, Joshua Miller. Just another impoverished luff, at thirty-five, old for his rank, and therefore probably under a cloud of some sort, doomed to remain a lieutenant until dismissal or death settled the matter. Avery had silenced the unspoken criticism by a casual mention of his admiral’s name, and the fact that the Millers had been making uniforms for the Bolithos for generations.

He nodded. “Very satisfactory.” His gaze shifted to the bright epaulette on his right shoulder. It would take some getting used to. A solitary epaulette on the right shoulder had formerly been the mark of rank for a captain, not posted, but a captain for all that. Their Lordships, apparently at the insistence of the Prince Regent, had changed it. The solitary epaulette now signified the rank of lieutenant, at least until some new fashion was approved.

The room darkened, and he imagined that the sky was cloud-ing over again. But it was a carriage, which had stopped in the street directly opposite the window: a very elegant vehicle in deep blue, with some sort of crest on the panels. A footman had climbed down and was lowering the step. It had not been lost on the tailor: he was hurrying to his door and opening it, admitting the bitter air from the street.

Curious, Avery thought, that in all the shops he had seen 36

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

there appeared to be no shortages, as if war with France and the new hostilities with America were on another planet.

He watched absently as a woman emerged from the carriage.

She wore a heavy, high-waisted coat almost the same colour as the paintwork, and her face was partly hidden by the deep brim of her bonnet as she looked down for the edge of the pavement.

Arthur Crowe bowed stiffly, his tape measure hanging around his neck like a badge of office.

“What a pleasure to see you again, my lady, on this fine brisk morning!”

Avery smiled privately. Crowe obviously made a point of knowing those who mattered, and those who did not.

He thought of Catherine Somervell, wondering if she had persuaded Bolitho to patronize this prosperous street.

Then he swung away, his mind reeling, the new epaulette, the shop, everything fading like fragments of a dream.

The door closed, and he barely dared to turn round.

Crowe said, “If you are certain I can provide nothing more, Mr Avery?”

Avery faced the door. The tailor was alone. Crowe asked, “Is something wrong, sir?”

“That lady.” He made himself look, but even the carriage had gone. Another fragment. “I thought I knew her.” Crowe watched his assistant parcelling up the new boat-cloak Avery had purchased. “Her husband was a good customer. We were sorry to lose him, although not always an easy man to sat-isfy.” He seemed to realize that it was not the answer Avery had wanted. “Lady Mildmay. The wife, or should I say, the widow, of Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Mildmay.”

It was she. Except that when he had last seen her, she had been only the wife of his captain in the old Canopus.

Crowe prompted, “Was that the lady of your acquaintance?”

“I think I was mistaken.” He picked up his hat. “Please have CROSS OF S T GEORGE

37

the other purchases delivered to the address I gave you.” No arguments, no hesitation. Sir Richard Bolitho’s name opened many doors.

He walked out into the street, glad to be moving again. Why should he care? Why did it matter so much? She had been unreachable then, when he had been stupid enough to believe it was more than just an amusing game to her, a passing flirtation.

Had she changed? He had caught a glimpse of her hair, honey-coloured; how many days, how many sleepless nights he had tried to forget it. Perhaps she had been part of the reason he had not resisted when his uncle, then Sir Paul Sillitoe, had suggested that he offer himself for the position of flag lieutenant to Sir Richard Bolitho. He had expected his application to be refused as soon as Bolitho had learned more about him. Instead, he had never forgotten that day in Falmouth, in the old house he had come to know so well, their kindness to him, the trust, and eventually the friendship which had done so much to heal the doubts and the injuries of the past. He had thought little more beyond the next voyage, the next challenge, even though it took him to the cannon’s mouth yet again.

And now, this. It had been a shock. He had deluded himself.

What chance would he have had? A married woman, and the wife of his own captain? It would have been like putting a pistol to his head.

Was she still as beautiful? She was two years older than himself, maybe more. She had been so alive, so vivacious. After the slur of the court martial, and then being marooned on the old Canopus, he thought until the end of his service, she had been like a bright star: he had not been the only officer who had been captivated. He quickened his pace, and halted as someone said,

“Thank you, sir!”

There were two of them. Once they had been soldiers; they even wore the tattered remnants of their red coats. One was blind, 38

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

and held his head at an angle as though he were trying to picture what was happening. The other had only one arm, and was clutching a hunk of bread which had obviously been handed to him by a pot-boy from the nearby coffee-house. It had probably been left on someone’s plate.

The blind man asked, “What is it, Ted?” The other said, “Bit o’ bread. Don’t worry. We might get lucky.”

Avery could not control his disgust. He should have been used to it, but he was not. He had once come to blows with another lieutenant who had taunted him about his sensitivity.

He said sharply, “You there!” and realized that his anger and dismay had put an uncharacteristic edge to his voice. The one-armed man even cowered, but stood protectively between the officer and his blind companion.

Avery said, “I am sorry.” He was reminded suddenly of Adam Bolitho, and the presentation sword he had sold. “Take this.” He thrust some money into the grimy hand. “Have something hot to eat.”

He turned away, annoyed that such things could still move and trouble him.

He heard the blind man ask, “Who was that, Ted?” The reply was barely audible above the clatter of wheels and harness.

“A gentleman. A true gentleman.”

How many were there like that? How many more would there be? Probably soldiers from a line regiment, maybe two of Wellington’s men: shoulder to shoulder, facing French cavalry and artillery.

Living from battle to battle, until luck changed sides and turned on them.

Those around him did not realize what it was like, and would never believe that either he or his admiral could still be moved by such pitiful reminders of the cost of war. Like that moment CROSS OF S T GEORGE

39

in Indomitable’s cabin after Adam’s ship had been lost, and a single survivor had been dragged from the sea by the brig Woodpecker, which, against orders, had returned to the scene. That survivor had been the ship’s boy. Avery had watched Bolitho bring the child back to life with his compassion, even as he had endeavoured to discover what had happened to Adam.

Avery had once believed that his own suffering had left him indifferent to the fate of others. Bolitho had convinced him otherwise.

Somewhere a clock chimed: St James’s, Piccadilly, he thought.

He had passed it without noticing it. He looked back, but the two redcoats had gone. Like ghosts, momentarily released from some forgotten field of battle.

“Why, Mister Avery! It is you.” He stared at her, vaguely aware that she was standing in the doorway of a perfumery, with a prettily wrapped box in her arms.

It was as if the street had emptied, and, like the two ghosts, had lost all identity.

He hesitated, and removed his hat, saw her eyes move over his face, and, no doubt, he thought bitterly, the dark hair which was so thickly streaked with grey. This was the moment he had lived in his dreams, when he would sting her with sarcasm and contempt, and punish her in a way she could never forget.

She wore a fur muff on one hand, and the parcel was in danger of falling. He said abruptly, “Let me assist you,” and took it from her; it was heavy, but he scarcely noticed. “Is there someone who will carry this for you?”

She was gazing at him. “I saw what you did for those poor beggars. It was kind of you.” Her eyes rested briefly on the new epaulette. “Promotion too, I see.”

“I fear not.” She had not changed at all. Beneath the smart bonnet her hair was probably shorter, as the new fashions dictated. But her eyes were as he remembered them. Blue. Very blue.

40

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

She seemed to recall his question. “My carriage will return for me in a moment.” Her face was full of caution now, almost uncertainty.

Avery said, “I imagined that I saw you earlier. A trick of the light, I daresay. I heard that you had lost your husband.” A moment of triumph. But it was empty.

“Last year . . .”

“I read nothing of it in the Gazette, but then, I have been away from England.” He knew he sounded curt, discourteous, but he could not help it.

She said, “It was not in battle. He had been in poor health for some time. And what of you? Are you married?”

“No,” he said.

She bit her lip. Even that little habit was painful to see. “I believe I read somewhere that you are aide to Sir Richard Bolitho.” When he remained silent she added, “That must be vastly excit-ing. I have never met him.” The slightest hesitation. “Nor have I met the famous Lady Somervell. I feel the poorer for it.” Avery heard the sound of wheels. So many others, but somehow he knew it was the carriage that matched her coat.

She asked suddenly, “Are you lodging in town?”

“I have been staying in Chelsea, my lady. I shall be leaving for the West Country when I have arranged my affairs in London.” There were two vivid spots of colour in her cheeks, which were not artificial. “You did not always address me so formally. Had you forgotten?”

He heard the carriage slowing down. It would soon be over: the impossible dream could not harm him any more. “I was in love with you then. You must have known that.” Boots clattered on the pavement. “Just the one, m’ lady?” She nodded, and watched with interest as the footman took the box from Avery, noting his expression, the tawny eyes she had always remembered.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

41

She said, “I have reopened the house in London. We had been living at Bath. It is not the same any more.” The footman lowered the step for her. He did not spare Avery even a glance.

She rested one hand on the carriage door. Small, well-shaped, strong.

She said, “It is not far from here. I like to be near the centre of things.” She looked up at him, searching his face, as though considering something. “Will you take tea with me? Tomorrow?

After all this time . . .”

He watched her, thinking of when he had held her. Kissed her. The only delusions had been his own.

“I think it would be unwise, my lady. There is enough gossip and slander in this town. I’ll not trouble you again.” She was inside the carriage but had lowered the window, while the footman waited, wooden-faced, to climb up beside the coachman.

For a moment she rested her hand on his, and he found himself surprised by her apparent agitation.

“Do come.” She slipped a small card into his hand. Then she glanced quickly at the footman and whispered, “What you said to me just now. Were you really?”

He did not smile. “I would have died for you.” She was still staring back at him as the dark blue carriage pulled away.

He jammed on his hat and said aloud, “Hell’s teeth, I still would!”

But the anger eluded him, and he added softly, “Susanna.” Yovell, Bolitho’s portly secretary, waited patiently near the library desk, his ample buttocks turned toward the fire. Sharing Bolitho’s life at sea as he did, Yovell knew, more than any one, the full extent of the planning and detail through which the 42

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

admiral had to sift before eventually translating this paper war into written orders for his captains.

Like Bolitho’s other loyal, if difficult, servant Ozzard, Yovell had a small cottage on the estate, even as Allday had lived there when home from the sea. Yovell gave a small, amused smile. That was, until Allday had suddenly become a respectable married man.

Through one of the windows he saw a cat waiting expectantly for somebody to open the door. That was Allday to a letter, he thought, on the wrong side of every door. When he was at sea he worried about his wife and the inn at Fallowfield, and now there was the baby to add to his responsibilities. And when he was home, he fretted about being left on the beach when Bolitho returned to his flagship. Yovell had no such domestic problems.

When he wanted to give up his present work he knew Bolitho would release him, just as he knew that many people thought him quite mad to risk his life in a man-of-war.

He watched Bolitho leafing through the pile of papers, which he had been examining for most of the morning. He had only returned from London a week ago and had been occupied with Admiralty business for much of the time. Catherine Somervell had waved to him as she had left the house to call on Lewis Roxby, their near neighbour and “the King of Cornwall,” as he was dubbed behind his back. Roxby was married to Bolitho’s sister Nancy, and Yovell thought it a good thing that Catherine had family of sorts to visit while they were all away at sea.

He admired her greatly, although he knew that many men called her a whore. When the transport Golden Plover had been wrecked off the coast of Africa, Bolitho’s woman had been with them, and had not only survived the hardships of their voyage in an open boat, but had somehow held them all together, given them heart and hope when they had no reason to expect that they would live. It had made his own suffering seem almost incidental.

Bolitho looked up at him, his face remarkably calm and rested.

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

43

Two weeks on the road from London, changing coaches and horses, being diverted by floods and fallen trees: their account of it had sounded like a nightmare.

Bolitho said, “If you would arrange for copies of these, I should like them despatched to Their Lordships as soon as possible.” He stretched his arms, and thought of the letter which had been awaiting his return. From Belinda, even though there was a lawyer’s hand at the helm. She needed more money, a sizeable increase in her allowance, for herself and their daughter Elizabeth. He rubbed the damaged eye. It had not troubled him very much since his return; perhaps the grey stillness of a Cornish winter was kinder than blazing sun and the sea’s mirrored reflections.

Elizabeth. She would be eleven years old in a few months’

time. A child he did not know, nor would he ever know her.

Belinda would make certain of that. He sometimes wondered what her friends in high society would think of the elegant Lady Bolitho if they knew she had connived with Catherine’s husband to have her falsely charged and transported like a common thief.

Catherine never spoke of it now, but she could never forget it.

And like himself, she would never forgive.

Every day since their return they had tried to enjoy to the full, knowing that time did not favour them. The roads and lanes were firmer after days of a steady south-easterly, and they had ridden for miles around the estate and had visited Roxby, who remained in poor health after suffering a stroke. Poor humour, too: Roxby adored his style of living, hunting and drinking, and entertaining lavishly at his house on the adjoining estate, balancing the pleasures of a gentleman with his obligations as farmer and magistrate.

He was even on intimate terms with the Prince Regent, and perhaps had been given his knighthood on the strength of that acquaintance. The advice of his doctors to rest and take things more quietly was like a sentence of death.

He thought of the long journey home on those appalling roads.

44

CROSS OF S T GEORGE

Catherine had even managed to create happiness then, despite her discomfort. At one point they had been turned back by flood-ing, and set down at a small, shabby inn which had clearly shocked their fellow passengers, two well-dressed churchmen and their wives who were on their way to meet their bishop.

One of the women had said angrily, “No lady should be expected to remain in such a dreadful place!” To Bolitho she had added, “What does your wife have to say about it, I should like to know?”

Catherine had answered, “We are not married, ma’am.” She had held his arm more tightly. “This officer is running away with me!”

They had not seen their fellow passengers again. Either they had waited for another coach, or had slipped away in the night.

The room had been damp and slightly musty from lack of use, but the landlord, a jovial dwarf of a man, had soon got a fire going, and the supper he had presented would have satisfied even the greediest midshipman.

And with the rain on the window, and the fire’s dancing shadows around them, they had sunk into the feather bed and made love with such abandon that they might well have been eloping.

There had been a short letter from Adam, saying only that he was leaving with Valentine Keen for Halifax, and asking their forgiveness for not having visited them in Falmouth.

Whenever he considered their situation his mind seemed to flinch from it. Adam and Keen. The two of them together, flag captain and admiral. Like me and James Tyacke. But so different.

Two men who had loved the same woman, and Keen knew nothing about it. To share a secret was to share the guilt, Bolitho thought.

That same night at the inn, while they had lain exhausted by their love, Catherine had told him something else. She had taken CROSS OF S T GEORGE

45

Keen to Zennor, to the churchyard where Zenoria was buried. It was a good thirty miles from Falmouth, and they had stayed with friends of Roxby’s in Redruth overnight.

She had said, “Had we stayed anywhere else there would have been talk, more cruel gossip. I couldn’t risk that—there are still too many who wish us ill.”

Then she had told him that while Keen had been alone at the grave she had spoken with the verger. He was also the gardener, and, with his brother, the local carpenter, and had confided that he made all the coffins for the village and surrounding farms.

She said, “I thought I would ask him to see that fresh flowers were put on her grave throughout the year.” Bolitho had held her in the firelight, feeling her sadness at the memory, and what had gone before.

Then she had said, “He would take no payment, Richard. He told me that ‘a young sea captain’ had already arranged it with him. After that, I went into the church, and I could see Adam’s face as I saw it that day, when Val and Zenoria were married.” What strange and perverse fate had brought Adam and Keen together? It could restore, or just as easily destroy them.