Command a King’s Ship

Alexander Kent - A Bolitho Novel

Epilogue

To the Contessa with love

Danger and Death dance to the wild music of the gale, and when it is night they dance with a fiercer abandon, as if to allay the fears that beset the sailormen who feel their touch but see them not.

GEORGE H. GRANT

1 The Admiral’s Choice

An Admiralty messenger opened the door of a small anteroom and said politely, `If you would be so good as to wait, sir.' He stood aside to allow Captain Richard Bolitho to pass and added, `Sir John knows you are here.'

Bolitho waited until the door had closed and then walked to a bright fire which was crackling below a tall mantel. He was thankful that the messenger had brought him to this small room and not to one of the larger ones. As he had hurried into the Admiralty from the bitter March wind which was sweeping down Whitehall he had been dreading a confrontation in one of those crowded waiting-rooms, crammed with unemployed officers who watched the comings and goings of more fortunate visitors with something like hatred.

Bolitho had known the feeling, too, even though he had told himself often enough that he was better off than most. For he had come back to England a year ago, to find the country at peace, and the gowns and villages already filling with unwanted soldiers and seamen. With his home in Falmouth, an established estate, and all the hard-earned prize money he had brought with him, he knew he should have been grateful.

He moved away from the fire and stared down at the broad roadway below the window. It had been raining for most of the morning, but now the sky had completely cleared, so that the many puddles and ruts glittered in the harsh light like patches of pale blue silk. Only the steaming nostrils of countless horses which passed this way and that, the hurrying figures bowed into the wind, made a lie of the momentary colour.

He sighed. It was March, 1784, only just over a year since his return home from the West Indies, yet it seemed like a century.

Whenever possible he had quit Falmouth to make the long journey to London, to this seat of Admiralty, to try and discover why his letters had gone unanswered, why his pleas for a ship, any ship, had been ignored. And always the waitingrooms had seemed to get more and more crowded. The familiar voices and tales of ships and campaigns had become forced, less confident, as day by day they were turned away. Ships were laid up by the score, and every seaport had its full quota of a war's flotsam. Cripples, and men made deaf and blind by cannon fire, others half mad from what they had seen and endured. With the signing of peace the previous year such sights had become too common to mention, too despairing even for hope.

He stiffened as two figures turned a corner below the window. Even without the facings on their tattered red coats he knew they had been soldiers. A carriage was standing by the roadside, the horses nodding their heads together as they explored the contents of their feeding bags. The coachman was chatting to a smartly dressed servant from a nearby house, and neither took a scrap of notice of the two tattered veterans.

One of them pushed his companion against a stone balustrade and then walked towards the coach. Bolitho realised that the man left clinging to the stonework was blind, his head turned towards the roadway as if trying to hear where his friend had gone. It needed no words.

The soldier faced the coachman and his companion and held out his hand. It was neither arrogant nor servile, and strangely moving. The coachman hesitated and then fumbled inside his heavy coat.

At that moment another figure ran lightly down some steps and wrenched open the coach door. He was well attired against the cold, and the buckles on his shoes held the watery sunlight like diamonds. He stared at the soldier and then snapped angrily at his coachman. The servant ran to the horses' heads, and within seconds the coach was clattering away into the busy press of carriages and carts. The soldier stood staring after it and then gave a weary shrug. He returned to his companion, and with linked arms they moved slowly around the next corner.

Bolitho struggled with the window catch, but it was stuck fast, his mind reeling with anger and shame at what he had just seen.

A voice asked, `May I help, sir?' It was the messenger again.

Bolitho replied, `I was going to throw some coins to two crippled soldiers.' He broke off, seeing the mild astonishment in the messenger's eyes.

The man said, `Bless you, sir, you'd get used to such sights in London.'

`Not me.'

`I was going to tell you, sir, that Sir John will see you now.'

Bolitho followed him into the passageway again, conscious of the sudden dryness in his throat. He remembered so clearly his last visit here, a month ago almost to the day. And that time he had been summoned by letter, and not left fretting and fuming in a waiting-room. It had seemed like a dream, an incredible stroke of good fortune. It still did, despite all the difficulties which had been crammed into so short a time.

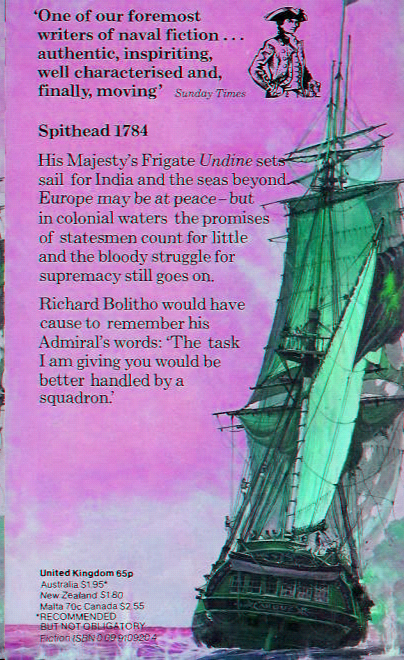

He was to assume command immediately of His Britannic Majesty's Ship Undine, of thirty-two guns, then lying in the dockyard at Portsmouth completing a refit.

As he had hurried from the Admiralty on that occasion he had felt the excitement on his face like guilt, aware of the other watching eyes, the envy and resentment.

The task of taking command, of gathering the dockyard's resources to his aid to prepare Undine for sea, had cost him dearly. With the Navy being cut down to a quarter of its wartime strength, he had been surprised to discover that it was harder to obtain spare cordage and spars rather than the reverse. A weary shipwright had confided in him that dockyard officials were more intent on making a profit with private dealers than they were on aiding one small frigate.

He had bribed, threatened and driven almost every man in the yard until he had obtained more or less what he needed. It seemed they saw his departure as the only way of returning to their own affairs.

He had walked around his new command in her dock with mixed feelings. Above all, the excitement and the challenge she represented. Gone were the pangs he had felt in Falmouth whenever he had seen a man-of-war weathering the headland below the castle. But also he had discovered something more.

His last command had been Phalarope, a frigate very similar to Undine, if slightly longer by a few feet. To Bolitho she had been everything, perhaps because they had come through so much together. In the West Indies, at the battle of the Saintes he had felt his precious Phalarope battered almost to a hulk beneath him. There would never, could never, be another like her. But as he had walked up and down the stone wall of the dock he had, sensed a new elation.

Halfway through the hurried overhaul he had received an unheralded visit from Rear Admiral Sir John Winslade, the man who had greeted him at the Admiralty. He had given little away, but after a cursory inspection of the ship and Bolitho's preparations he had said, `I can tell you now. I'm sending you to India. That's all I can reveal for the moment.' He had run his eye over the few riggers working on yards and shrouds and had added dryly, `I only hope for your sake you'll be ready on time.'

There was a lot in what Winslade had hinted. Officers on halfpay were easy to obtain. To crew a King's ship without the urgency of a war or the pressgang was something else entirely. Had Undine been sailing in better-known waters things might have been different. And had Bolitho been a man other than himself he might have been tempted to keep her destination a secret until he had signed on sufficient hands and it was too late for them to escape.

He had had the usual flowery-worded handbills distributed around the port and nearby villages. He had sent recruiting parties as far inland as Guildford on the Portsmouth Road, but with small success. And now, as he followed the messenger towards some high gilded doors he knew Undine was still fifty short of her complement.

In one thing Bolitho had been more fortunate. Undine's previous captain had kept a shrewd eye on his ship's professional men. Bolitho had taken charge to discover that Undine still carried the hard core of senior men, the warrant officers, a first class sailmaker, and one of the most economical carpenters he had ever watched at work. His predecessor had quit the Navy for good to seek a career in Parliament. Or as he had put it, `I've had a bellyful of fighting with iron. From now on, my young friend, I'll do it with slander!'

Rear Admiral Sir John Winslade was standing with his back to a fire, his coat-tails parted to allow the maximum warmth to reach him. Few people knew much about him. He had distinguished himself vaguely in some single-ship action off Brest, and had then been neatly placed inside the Admiralty. There was nothing about his pale, austere features to distinguish him in any way. In fact, he was so ordinary that his gold-laced coat seemed to be wearing him rather than the other way round.

Bolitho was twenty-seven and a half years old, but had already held two commands, and knew enough about senior officers not to take them at face value.

Winslade let his coat-tails drop and waited for Bolitho to reach him. He held out his hand and said, `You are punctual. It is just as well. We have much to discuss.' He moved to a small lacquered table. `Some claret, I think.' He smiled for the first time. It was like the sunlight in Whitehall. Frail, and easily removed.

He pulled up a chair for Bolitho. `Your health, Captain.' He added, `I suppose you know why I asked for you to be given this command?'

Bolitho cleared his throat. `I assumed, sir, that as Captain Stewart was entering politics that you required another for ...'

Winslade gave a wry smile. `Please, Bolitho. Modesty at the expense of sincerity is just so much top-hamper. I trust you will bear that in mind?'

He sipped at his claret and continued in the same dry voice, `For this particular commission I have to be sure of Undine's captain. You will be on the other side of the globe. I have to know what you are thinking so that I can act on such despatches as I might receive in due course.'

Bolitho tried to relax. `Thank you.' He smiled awkwardly. `I mean, for your trust, sir.'

`Quite so.' Winslade reached for the decanter. `I know your background, your record, especially in the recent war with France and her Allies. Your behaviour when you were on the American station reads favourably. A full scale war and a bloody rebellion inAmerica must have been a good schoolroom for so young a commander. But that war is done with. It is up to us,' he smiled slightly, `some of us, to ensure that we are never forced into such a helpless stalemate again.'

Bolitho exclaimed, `We did not lose the war, sir.'

`We did not win it either. That is more to the point.'

Bolitho thought suddenly of the last battle. The screams and yells on every side, the crash of gunfire and falling spars. So many had died that day. So many familiar faces just swept away. Others had been left, like the two ragged soldiers, to fend as best they could.

He said quietly, `We did our best, sir.'

The admiral was watching him thoughtfully. `I agree. You

may not have won a war, but you did win a respite of sorts. A

time to draw breath and face facts.'

`You think the peace will not last, sir?'

`An enemy is always an enemy, Bolitho. Only the vanquished

know peace of mind. Oh yes, we will fight again, be sure of it.' He put down his glass and added sharply, `Now, about your

ship. Are you prepared?'

Bolitho met his gaze. `I am still short of hands, but the ship is as ready as she will ever be, sir. I had her warped out of the dockyard two days ago, and she is now anchored at Spithead awaiting final provisioning.'

`How short?'

Two words, but they left no room for manoeuvre.

`Fifty, Sir. But my lieutenants are still trying to gather more.'

The admiral did not blink. `I see. Well, it's up to you. In the meantime I will obtain a warrant for you to take some "volunteers" from the prison hulks in Portsmouth harbour.'

Bolitho said, `It's a sad thing that we must rely on convicts.'

`They are men. That is all you require at the moment. As it is, you will probably be doing some of the wretches a favour. Most of 'em were to be transported to the penal colonies in America. Now, with America gone, we will have to look elsewhere for new settlements. There is some talk of Botany Bay, in New Holland, but it may be rumour, of course.'

He stood up and walked to a window. `I knew your father. I was saddened to hear of his death. While you were in the West Indies, I believe?' He did not wait for a reply. `This mission would have been well cut for him. Something to get his teeth into. Self-dependence, decisions to be made on the spot which could make or break the man in command. Everything a young frigate captain dreams of, right?'

`Yes, Sir.'

He pictured his father as he had last seen him. The very day he had sailed for the Indies in Phalarope. A tired, broken man. Made bitter by his other son's betrayal. Hugh Bolitho had been the apple of his eye. Four years older than Richard, he had been a born gambler, and had ended in killing a brother officer in a duel. Worse, he had fled to America, to join the Revolutionary forces and later to command a privateer against the British. It had been that knowledge which had really killed Bolitho's father, no matter what the doctor had said.

He tightened his grip on his glass. Much of his prize money had gone into buying back land which his father had sold to pay Hugh's debts. But nothing could buy back his honour. It was fortunate that Hugh had died. If they had ever met again Bolitho imagined he might kill him for what he had done.

`More claret?' Winslade seemed absorbed with his own thoughts. `I'm sending you to Madras. There you will report to ..., well, it will be in your final orders. No sense in idle gossip.' He added, `Just in case you cannot get your ship manned, eh?'

`I'll get them, sir. If I have to go to Cornwall.'

`I hope that will not be necessary.'

Winslade changed tack again. `During the American campaign you probably noticed that there was little co-operation between military and civilian government. The forces on the ground fought the battles and confided in neither. That must not happen again. The task I am giving you would be better handled by a squadron, with an admiral's flag for good measure. But it would invite attention, and that Parliament will not tolerate in this uneasy peace.'

He asked suddenly, `Where are you staying in London?'

`The George at Southwark.'

`I will give you an address. A friend's residence in St. James's Square.' He smiled at Bolitho's grave features. `Come, don't look so gloomy. It is time you made your way in affairs and put the line of battle behind you. Your mission may bring you to eyes other than those of jaded flag officers. Get to know people. It can do nothing but good. I will send a courier with instructions for your first lieutenant.' He darted him a quick glance. 'Herrick, I gather. From your last ship.'

`Yes, Sir.' It sounded like `of course'. There had never been any doubt whom he would ask for if he got another ship.

`Well then, Mr. Herrick it is. He can take charge of local matters. I'll need you in London for four days.' He hardened his tone as Bolitho looked about to protest. `At least!'

The admiral regarded Bolitho for several seconds. Craving to get back to his ship, uncertain of himself in these overwhelming surroundings. It was all there and more besides. As Bolitho had entered the room it had been like seeing his father all those long years ago. Tall, slim, with that black hair tied at the nape of his neck. The loose lock which hung above his right eye told another story. Once as he had raised his glass it had fallen aside to display a livid scar which ran high into the hairline. Winslade was glad about his choice. There was intelligence on Bolitho's grave features, and compassion too, which even his service in seven years of war had not displaced. He could have picked from a hundred captains, but he had wanted one who needed a ship and the sea and not merely the security such things represented. He also required a man who could think and act accordingly. Not one who would rest content on the weight of his broadsides. Bolitho's record had shown plainly enough that he was rarely content to use written orders as a substitute for initiative. Several admirals had growled as much when Winslade had put his name forward for command. But he had got his way, for Winslade had the weight of Parliament behind him, which was another rarity.

He sighed and picked up a small bell from the table.

`You go and arrange to move to the address I will give you. I have much to do, so you may as well enjoy yourself while you can.'

He shook the bell and a servant entered with Bolitho's cocked hat and sword. Winslade watched as the man buckled the sword deftly around his waist.

`Same old blade, eh?' He touched it with his fingers. It was very smooth and worn, and a good deal lighter than more modern swords.

Bolitho smiled. `Aye, sir. My father gave it to me after ...' `I know. Forget about your brother, Bolitho.' He touched

the hilt again. `Your family have brought too much honour

for many generations to be brought down by one man.'

He thrust out his hand. `Take care. I daresay there are quite

a few tongues wagging about your visit here today.'

Bolitho followed the servant into the corridor, his mind moving restlessly from one aspect of his visit to another. Madras, another continent, and that sounded like a mere beginning to whatever it was he was supposed to do.

Every mile sailed would have its separate challenge. He smiled quietly. And reward. He paused in the doorway and. stared at the bustling people and carriages. Open sea instead of noise and dirt. A ship, a living, vital being instead of dull, pretentious buildings.

A hand touched his arm, and he turned to see a young man in a shabby blue coat studying him anxiously.

`What is it?'

The man said quickly, `I'm Chatterton, Captain. I was once second lieutenant in the Warrior, seventy-four.' He hesitated; watching Bolitho's grave face. `I heard you were commissioning, sir, I was wondering ...'

`I'm sorry, Mr. Chatterton. I have a full wardroom.'

`Yes, sir, I had guessed as much.' He swallowed. `I could sign as master's mate perhaps?'

Bolitho shook his head. `It is only seamen I lack, I'm afraid.'

He saw the disappointment clouding the man's face. The old Warrior had been in the thick of it. She was rarely absent from any battle, and men had spoken her name with pride. Now her second lieutenant was waiting like a beggar.

He said quietly, `If I can help.' He thrust his hand into his pocket. `Tide you over awhile.'

`Thank you, no, sir.' He forced a grin. `Not yet anyway.' He pulled up his coat collar. As he walked away he called, `Good luck, Captain!'

Bolitho watched him until he was out of sight. It might have been Herrick, he thought. Any of us.

His Majesty's frigate Undine tugged resentfully at her cable as a stiffening south-easterly wind ripped the Solent into a mass of vicious whitecaps.

Lieutenant Thomas Herrick turned up the collar of his heavy watchcoat and took another stroll across the quarterdeck, his eyess slitted against a mixture of rain and spray which made the taut rigging shine in the poor light like black glass.

Despite the weather there was still plenty of activity on deck and alongside in the pitching store boats and water lighters. Here and there on the gangways and right forward in the eyes of the ship the red coats of watchful marines made a pleasant change from the mixtures of dull grey elsewhere. The marines were supposed to ensure that the traffic in provisions and lastmoment equipment was one way, and none was escaping through an open port as barter for cheap drink or other favours with friends ashore.

Herrick grinned and stamped his feet on the wet planking. They had done a lot of work in the month since he had joined the ship. Others might curse the weather, the uncertainties offered by a long voyage, the prospect of hardship from sea and wind, but not he. The past year had been far more of a burden for him, and he was glad, no thankful, to be back aboard a King's ship. He had entered the Navy when he was still a few weeks short of twelve years old, and these last long months following the signing of peace with France and the recognition of American independence had been his first experience of being away from the one life he understood and trusted.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Herrick had nothing but his own resources to sustain him. He came of a poor family, his father being a clerk in their home town of Rochester in Kent. When lie had gone there after paying off the Phalarope and saying his farewell to Bolitho, he had discovered things to be even worse than he had expected. His father's health had deteriorated, and he seemed to be coughing his life away, day in, day out. Herrick's only sister was a cripple and incapable of doing much but help her mother about the house, so his homecoming was seen in rather different ways from his own sense of rejection. A friend of his father's employer had gained him an appointment as mate in a small brig which earned a living carrying general cargo up and down the east coast and occasionally across the channel to Holland. The owner was a miserly man who kept the brig so shorthanded that there were barely enough men to work ship, let along handle cargo, load lighters and keep the vessel in good repair.

When he had received Bolitho's letter, accompanied by his commission from the Admiralty charging him to report on board Undine, he had been almost too stunned to realise his good fortune. He had not seen Bolitho since that one last visit to his home in Falmouth, and perhaps deep inside he had believed that their friendship, which had strengthened in storm and under bloody broadsides, would be no match for peace.

Their worlds were, after all, too far apart. Bolitho's great stone house had seemed like a palace to Herrick. His background, his ancestry of seafaring officers, put him in a different sphere entirely. Herrick was the first in his family to go to sea, and that was the least of their differences.

But Bolitho had not changed. When they had met on this same quarterdeck a month ago he had known it with that first glance. It was still there, The quiet sadness, which could give way to something like boyish excitement in the twinkling of an eye.

Above all, Bolitho too was pleased to be back, keen to test himself and his new ship whenever a chance offered itself.

A midshipman scuttled over the deck and touched his hat.

`Cutter's returning, sir.'

He was small, pinched with cold. He had been aboard just three weeks.

`Thank you, Mr. Penn. That'll be some new hands, I hope.' He eyed the boy unsympathetically. `Now smarten yourself, the captain may be returning today.'

He continued his pacing.

Bolitho had been in London for five days. It would be good to hear his news, to get the order to sail from this bitter Solent.

He watched the cutter lifting and plunging across the whitecaps, the oars moving sluggishly despite the efforts of the boat's coxswain. He saw the cocked hat of John Soames, the third lieutenant, in the sternsheets, and wondered if he had had any luck with recruits.

In the Phalarope Herrick had begun his commission as third lieutenant, rising to Bolitho's second-in-command as those above him died in combat. He wondered briefly if Soames was already thinking of his own prospects in the months ahead. He was a giant of a man and in his thirtieth year, three years older than Herrick, He had got his commission as lieutenant very late in life, and by a roundabout route, mostly, as far as Herrick could gather, in the merchant service and later as master's mate in a King's ship. Tough, self-taught, he was hard to know. A suspicious man.

Quite different from Villiers Davy, the second lieutenant. As his name suggested, he was of good family, with the money and proud looks to back up his quicksilver wit. Herrick was not sure of him either, but told himself that any dislike he might harbour was because Davy reminded him of an arrogant midshipman they had carried in Phalarope.

Feet thumped on deck and he turned to see Triphook, the purser, crouching through the drizzle, a bulky ledger under his coat.

The purser grimaced.. `Evil day, Mr. Herrick.' He gestured to the boats alongside. `God damn those thieves. They'd rob a blind man, so they would.'

Herrick chuckled. `Not like you pursers, eh?'

Triphook eyed him severely. He was stooped and very thin, with large yellow teeth like a mournful horse.

`I hope that was not seriously meant, sir?'

Herrick craned over the dripping nettings to watch the cutter hooking on to the chains. God, their oarsmanship was bad. Bolitho would expect far better, and before too long.

He snapped, `Easy, Mr. Triphook. But I was merely reminding you. I recall we had a purser in my last ship. A man called Evans. He lined his pockets at the people's expense. Gave them foul food when they had much to trouble them in other directions.'

Triphook watched him doubtfully. `What happened?'

`Captain Bolitho made him pay for fresh meat from his own purse. Cask for cask with each that was rotten.' He grinned. `So be warned, my friend!'

`He'll have no cause to fault me, Mr. Herrick.' He walked away, his voice lacking conviction as he added, `You can be certain of that.'

Lieutenant Soames came aft, touching his hat and scowling at the deck as he reported, `Five hands, sir. I've been on the road all day, I'm fair hoarse from calling the tune of those handbills.'

Herrick nodded. He could sympathise. He had done it often enough himself. Five hands. They still needed thirty. Even then it would not allow for death and injury to be expected on any long voyage.

Soames asked thickly, `Any more news?'

‘None. Just that we are to sail for Madras. But I think it will be soon now.'

Soames said, `Good riddance to the land, I say. Streets full of drunken men, prime hands we could well do with.' He hesitated. `With your permission I might take a boat away tonight and catch a few as they reel from their damn ale houses, eh?'

They turned as a shriek of laughter echoed up from the gun deck, and a woman, her breasts bare to the rain, ran from beneath the larboard gangway. She was pursued by two seamen, both obviously the worse for drink, who left little to the imagination as to their intentions.

Herrick barked, `Tell that slut to get below! Or I'll have her thrown over the side!' He saw the astonished midshipman watching the spectacle with wide-eyed wonder and added harshly, `Mr. Penn! Jump to it, I say!'

Soames showed a rare grin. `Offend your feelings, Mr. Herrick?'

Herrick shrugged. `I know it is supposed to be the proper thing to allow our people women and drink in harbour.' He thought of his sister. Anchored in that damned chair. What he would give to see her running free like that Portsmouth trollop. `But it never fails to sicken me.'

Soames sighed. `Half the bastards would desert otherwise, signed on or not. The romance of Madras soon wears off when the rum goes short.'

Herrick said, `What you asked earlier. I cannot agree. It would be a bad beginning. Men taken in such a way would harbour plenty of grievances. One rotten apple can sour a full barrel.'

Soames eyes him calmly. `It seems to me that this ship is almost full of bad apples. The volunteers are probably on the run from debt, or the hangman himself. Some are aboard just to see what they can lay their fingers on when we are many miles from proper authority.'

Herrick replied, `Captain Bolitho will have sufficient authority, Mr. Soames.'

`I forgot. You were in the same ship. There was a mutiny.' It sounded like an accusation.

`Not of his making.' He turned on him angrily. `Be so good as to have the new men fed and issued with slop clothing.'

He waited, watching the resentment in the big man's eyes.

He added, `Another of our captain's requirements. I suggest you acquaint yourself with his demands. Life will be easier for you.'

Soames strode away and Herrick relaxed. He must not let him get into his skin so easily. But any criticism, or even hint of it, always affected him. To Herrick, Bolitho represented all the things he would like to be. The fact he also knew some of his secret faults as well made him doubly sure of his loyalty. He shook his head. It was stronger even than that.

He peered over the nettings towards the shore, seeing the walls of the harbour battery glinting like lead in the rain. Beyond Portsmouth Point the land was almost hidden in murk. It would be good to get away. His pay would mount up, and go towards helping out at home. With his share of prize money which he gained under Bolitho in the West Indies he had been able to buy several small luxuries to make their lot easier until his next return. And when might that be? Two years? It was better never to contemplate such matters.

He saw a ship's boy duck into the rain to turn the hour-glass beside the deserted wheel, and waited for him to chime the hour on the bell. Time to send the working part of the watch below. He grimaced. The wardroom might be little better. Soames under a cloud of inner thought. Davy probing his guard with some new, smart jest or other. Giles Bellairs, the captain of marines, well on the way to intoxication by this time, knowing his hefty sergeant could deal with the affairs of his small detachment. Triphook probably brooding over the issue of clothing to the new men. Typical of the purser. He could face the prospect of a great sea voyage, with each league measured in salt pork and beef, iron-hard biscuit, juice to prevent scurvy, beer and spirits to supplement fresh water which would soon be alive in its casks, and all the thousand other items under his control, with equanimity. But one small issue of clothing, while they still wore what they had come aboard in, was too much for his sense of values. He would learn. He grinned into the cold wind. They all would, once Bolitho brought the ship alive.

More shouts from alongside, and Penn, the midshipman, called anxiously, `Beg pardon, sir, but I fear the surgeon is in difficulties.'

Herrick frowned. The surgeon's name was Charles Whitmarsh. A man of culture, but one with something troubling him. Most ship's surgeons, in Herrick's experience, had been butchers. Nobody else would go to sea and face the horrors of mangled men screaming and dying after a savage battle with the enemy. In peacetime he had expected it might be different.

Whitmarsh was a drunkard. As Herrick peered down at the jolly boat as it bobbed and curtsied at the chains, he saw a boatswain's mate and two seamen struggling to fit the surgeon into a bowline to assist his passage up the side. He was a big man, almost as large as Soames, and in the grey light his features shone with all the brightness of a marine's coat.

Herrick snapped, `Have a cargo net lowered, Mr. Penn. It is not dignified, but neither is this, by God!'

Whitmarsh landed eventually on the gun deck, his hair awry, his face set in a great beaming smile. One of his assistants and two marines lifted him bodily and took him aft below the quarterdeck. He would sleep in his small sickbay for a few hours, and then begin again.

Penn asked nervously, `Is he unwell, sir?'

Herrick looked at the youth gravely. `A thought tipsy, lad, but well enough to remove a limb or two, I daresay.' He relented and touched his shoulder. `Go below. Your relief will be up soon.'

He watched him hurry away and grinned. It was hard to recall that he had been like Penn. Unsure, frightened, with each hour presenting some new sight and sound to break his boy's illusions.

A marine yelled, 'Guardboat shovin' off from the sallyport, Sir!'

Herrick nodded. `Very well.'

That would mean orders for the Undine. He let his gaze move forward between the tall, spiralling masts with their taut maze of shrouds and rigging, the neatly furled canvas and to the bowsprit, below which Undine's beautiful, full-breasted figurehead of a water-nymph stared impassively to every horizon. It also meant that Bolitho would be returning. Today.

And for Thomas Herrick that was more than enough.

2

Free of the Land

Captain Richard Bolitho stood in the shelter of the stone wall beside the sallyport and peered through the chilling drizzle. It was afternoon, but with the sky so overcast by low cloud it could have been much later.

He was tired and stiff from the long coach ride, and the journey had been made especially irritating by his two jovial companions. Businessmen from the City of London, they had become more loud-voiced after each stop for change of horses and refreshment at the many inns down the Portsmouth road. They were off to France in a packet ship, to contact new agencies there, and so, with luck, expand their trade. To Bolitho it was still hard to accept. Just a year back the Channel had been the only barrier between this country and their common enemy. The moat. The last ditch, as some news-sheet had described it. Now it seemed as if it was all forgotten by such men as his travelling companions. It had become merely an irritating delay which made their journey just so much longer.

He shrugged his shoulders deeper inside his boat-cloak, suddenly impatient for the last moments to pass, so that he could get back to the ship. The cloak was new, from a good London tailor. Rear Admiral Winslade's friend had taken him there, and managed to do so without making Bolitho feel the complete ignoramus. He smiled to himself despite his other uncertainties. He would never get used to London. Too large, too busy, where nobody had time to draw breath. And noisy. No wonder the rich houses around St. James's Square had sent servants out every few hours to spread fresh straw on the roadway. The grinding roar of carriage wheels was enough to wake the dead. It had been a beautiful house, his hosts charming, if slightly amused by his questions. Even now, he was still unsure of their strange ways. It was not just enough to live in that fine, fashionable residence, with its splendid spiral staircase and huge chandeliers. To be right, you had to live on the best side of the square, the east side. Winslade's friends lived there. Bolitho smiled again. They would.

Bolitho had met several very influential people, and his hosts had given two dinner parties with that in mind. He knew well enough from past experience that without their help it would have been impossible. Aboard ship a captain was next only to God. In London society he hardly registered at ail.

But that was behind him now. He was back. His orders would be waiting, and only the actual time of weighing anchor was left to conjecture.

He peered round the wall once more, feeling the wind on his face like a whip. The signal tower had informed Undine of his arrival, and very soon now a boat would arrive at the wooden pier below the wall. He wondered how his coxswain, Allday, was managing. His first ship as captain's coxswain, but Bolitho understood him well enough to know there was little to fear on his behalf. It would be good to see him, too. Something familiar. A face to hold on to.

He glanced up the narrow street to where some servants from the George Inn, where the coach had finally come to rest, were guarding his pile of luggage. He thought of the personal purchases he had made. Maybe London had got some hold on him after all.

When Bolitho had got his first command of the sloop Sparrow during the American Revolution, he had had little time to acquaint himself with luxuries. But in London, with the remains of his prize money, he had made up for it. New shirts, and some comfortable shoes. This great boat-cloak, which the tailor had assured him would keep out even the heaviest downpour. It had been partly Winslade's doing, he was certain of that. His host had casually mentioned that Bolitho's mission in Undine required not merely a competent captain, but one who would look the part, no matter what sort of government official he might meet. There was, he had added gently, a matter of wine.

Together they had gone to a low-beamed shop in St. James's Street. It was not a bit what Bolitho might have imagined. It had the sign of a coffee mill outside its door, and the owners' names, Pickering and Clarke, painted in gold leaf above. It was a friendly place, even intimate. It could almost have been Falmouth.

It was to be hoped the wine had already arrived aboard Undine. Otherwise, it was likely he would have to sail without it, and leave a large hole in his purse as well.

It would be a strange and exciting. sensation to sit in his cabin, hundreds of miles from England, and sample some of that beautiful madeira. It would bring back all those pictures of London again. The buildings, the clever talk, the way women looked at you. Once or twice he had felt uneasy about that. It had reminded him bitterly of New York during the war. The boldness in their faces. The confident arrogance which had seemed like second nature to them.

An idler called, 'Yer boat's a-comin', Cap'n!' He touched his hat. 'I'll give 'ee a 'and!' He hurried away to call the inn servants, his mind dwelling on what he might expect from a frigate's captain.

Bolitho stepped out into the wind, his hat jammed well down over his forehead. It was the Undine's launch, her largest boat, the oars rising and falling like gulls' wings as she headed straight for the pier. It must be a hard pull, he thought. Otherwise Allday would have brought the gig.

He found he was trembling, and it was all he could do to prevent a grin from splitting his face in two. The dark green launch, the oarsmen in their checked shirts and white trousers, it was all there. Like a homecoming.

The oars rose in the air and stood like twin lines of swaying white bones, while the bowman made fast to the jetty and aided a smart midshipman to step ashore.

The latter removed his hat with a flourish and said, `At your service, sir.'

It was Midshipman Valentine Keen, a very elegant young man who was being appointed to the Undine more to get him away from England than to further his naval advancement, Bolitho suspected. He was the senior midshipman, and if he survived the round voyage would probably return as a lieutenant. At any rate, as a man.

'My boxes are yonder, Mr. Keen.'

He saw Allday standing motionless in the sternsheets, his blue coat and white trousers flapping in the wind, his tanned features barely able to remain impassive.

Theirs was a strange relationship. Allday had come aboard Bolitho's last ship as a pressed man. Yet when the ship had paid off at the end of the war Allday had stayed with him at Falmouth. Servant; guardian. Trusted friend. Now as his coxswain he would be ever nearby. Sometimes an only contact with that other, remote world beyond the cabin bulkhead.

Allday had been a seaman all his life, but for a period when he had been a shepherd in Cornwall, where Bolitho's pressgang had found him. An odd beginning. Bolitho thought of his previous coxswain, Mark Stockdale. A battered ex-prizefighter who could hardly speak because of his maimed vocal cords. He had died protecting Bolitho's back at the Saintes. Poor Stockdale. Bolitho had not even seen him fall.

Allday clambered ashore.

`Everything's ready, Captain. A good meal in the cabin.' He snarled at one of the seamen, `Grab that chest, you oaf, or I'll have your liver!'

The seaman nodded and grinned.

Bolitho was satisfied. Allday's strange charm seemed to be working already. He could curse and fight like a madman if required. But Bolitho had seen him caring for wounded men and knew his other side. It was no wonder that the girls in farms and villages around Falmouth would miss him. Better though for Allday, Bolitho decided. There had been rumours enough lately about his conquests.

Then at last it was all done. The boat loaded, the idler and servants paid. The oars sending the long launch purposefully through the tossing water.

Bolitho sat in silence, huddled in his cloak, his eyes on the distant frigate. She was beautiful. In some ways more so than Phalarope, if that were possible. Only four years old, she had been built in a yard at Frindsbury on the River Medway. Not far from Herrick's home. One hundred and thirty feet long on her gun deck, and built of good English oak, she was the picture of a shipbuilder's art. No wonder the Admiralty had been loath to lay her up in ordinary like so many of her consorts at the end of the war. She had cost nearly fourteen thousand pounds, as Bolitho had been told more than once. Not that he needed to be reminded. He was lucky to get her.

There was a brief break in the scudding clouds, and the watery light played down along Undine's gun ports to her clean sheathing as she rolled uneasily in the swell. Best Anglesey copper. Stout enough for anything. Bolitho recalled what her previous captain, Stewart, had confided. In a fierce skirmish off Ushant he had been raked by heavy guns from a French seventy-four. Undine had taken four balls right on her waterline. She had been fortunate to reach England afloat. Frigates were meant for speed and hit-and-run fighting, not for matching metal with a line of battleship. Bolitho knew from his own grim experience what that could do to so graceful a hull.

Stewart had added that despite careful supervision he was still unsure as to the perfection of the repairs. With the copper replaced, it took more than internal inspection to discover the true value of a dockyard's overhaul. Copper protected the hull from many sorts of weed and clinging growth which could slow a ship to a painful crawl. But behind it could lurk every captain's real enemy, rot. Rot which could change a perfect hull into a ripe, treacherous trap for the unwary. Admiral Kempenfelt's own flagship, the Royal George, had heeled over and sunk right here in Portsmouth just two years ago, with the loss of hundreds of lives. It was said that her bottom had fallen clean away with rot. If it could happen to a lofty first-rate at anchor, it would do worse to a frigate.

Bolitho came out of his thoughts as he heard the shrill of boatswain's calls above the wind, the stamp of feet as the marines prepared to receive him. He stared up at the towering masts, the movement of figures around the entry port and above in the shrouds. They had had a month to get used to seeing him about the ship, except for the unknown quantity, the newly recruited part of the company. They might be wondering about him now. What he was like. Too harsh, or too easy-going. To them, once the anchor was catted, he was everything, good or bad, skilful or incompetent. There was no other ear to listen to their complaints, no other voice to reward or punish.

`Easy all!' Allday stood half poised, the tiller bar in his fist. `Toss your oars!'

The boat thrust forward and the bowman hooked on to the main chains. at the first attempt. Bolitho guessed that Allday had been busy during his stay in London.

He stood up and waited for the right moment, knowing Allday was watching like a cat in case he should slip between launch and ship, or worse, tumble backwards in a welter of flailing arms and legs. Bolitho had seen it happen, and recalled his own cruel amusement at the spectacle of his new captain arriving aboard in a dripping heap.

Then, with the spray barely finding time to catch his legs, he was up and on board, his ears ringing to the shrill of calls and to the slap of marines' muskets while they presented arms. He doffed his hat to the quarterdeck, and nodded to Herrick and the others.

`Good to be back, Mr. Herrick.' His tone was curt.

`Welcome aboard, sir.' Herrick was equally so. But their eyes shone with something more than routine formality. Something which none of the others saw, or shared.

Bolitho removed his cloak and handed it to Midshipman Penn. He turned to allow the fading light to play across the broad white lapels of his dress coat. They would all know he was here. He saw the few hands working aloft on last minute splicing, others crowded on gangways and down on the main deck between the twin lines of black twelve-pounder guns.

He smiled, amused at his own gesture. `I will go below now.'

`I have placed the orders in your cabin, sir.'

Herrick was bursting with questions. It was obvious from his flat, formal voice. But his eyes, those eyes which were so blue, and which could look so hurt, made a lie of his rigidity.

`Very well, I will call you directly.'

He made to walk aft to the cabin hatchway when he saw some figures gathered just below the quarterdeck rail. In mixed garments, they were in the process of being checked against a list by Lieutenant Davy.

He called, `New hands, Mr. Davy?'

Herrick said quietly, `We are still thirty under strength, sir.'

`Aye, Sir.' Davy squinted up through the light drizzle, his

handsome face set in a confident smile. `I am about to get them

to make their marks.'

Bolitho crossed to the ladder and ran down to the gun deck. God, how wretched they all looked. Half-starved, ragged, beaten. Even the demanding life aboard ship could surely be no worse than what had made them thus.

He watched Davy's neat, elegant hands as he arranged the book on top of a twelve-pounder's breech.

`Come along now, make your marks.'

They shuffled forward, self-conscious, awkward, and very aware that their new captain was nearby.

Bolitho's eye stopped on the one at the end of the line. A sturdy man, well-muscled, and with a pigtail protruding from beneath his battered hat. One prime seaman at least.

He realised Bolitho was watching him and hurried forward to the gun.

Davy snapped, `Here now, hold your damn eagerness!' Bolitho asked, `Your name?' He hesitated. 'Turpin, sir.'

Davy was getting angry. `Stand still and remove your hat to the captain, damn your eyes! If you know anything, you should know respect!'

But the man stood stockstill, his face a mixture of despair and shame.

Bolitho reached out and removed an old coat which Turpin had been carrying across his right forearm.

He asked gently, `Where did you lose your right hand, Turpin?'

The man lowered his eyes. `I was in the Barfear, sir. I lost it at the Chesapeake in '81.' He looked up, his eyes showing pride, but only briefly. `Gun captain, I was, sir.'

Davy interjected, `I am most sorry, sir. I did not realise the fellow was crippled. I will have him sent ashore.'

Bolitho said, `You intended to sign the articles with your left hand. Is it that important?'

Turpin nodded. `I'm a seaman, sir.' He looked round angrily as one of the recruited men nudged his companion. `Not like some!' He turned back to Bolitho, his voice falling away. `I can do anything, sir.'

Bolitho hardly heard him. He was thinking back to the Chesapeake. The smoke and din. The columns of wheeling ships, like armoured knights at Agincourt. You never got away

from it. This man Turpin had been nearby, like hundreds of others. Cheering and dying, cursing and working their guns like souls possessed. He thought of the two fat merchants on the coach. So men like that could grow richer.

He said harshly, `Sign him on, Mr. Davy. One hand from the old Barfleur will be more use to me than many others.'

He strode aft beneath the quarterdeck, angry with himself, and with Davy for not having the compassion to understand. It was a stupid thing to do. Pointless.

Allday was carrying one of the chests aft to the cabin, where a marine stood like a toy soldier beneath the spiralling deckhead lantern.

He said cheerfully, `That was a good thing you just did, Captain.'

`Don't talk like a fool, Allday!' He strode past' him and winced as his head grazed an overhead beam. When he glared back at Allday his coxswain's homely features were quite expressionless. `He could probably doyour work.'

Allday nodded gravely. `Aye, sir, it is true that I am overtaxed!'

`Damn your impertinence!' It was useless with Allday. `I don't know why I tolerate you!'

Allday took his sword and walked with it to the cabin bulkhead.

`I once knew a man in Bodmin, Captain.' He stood back and studied the sword critically. `Used to hammer a block of wood with a blunt axe, he did. I asked him why he didn't use a sharper blade and finish the job properly.' Allday turned and smiled calmly. `He said that when the wood was broken he'd have nothing to work his temper on.'

Bolitho sat down at the table. `Thank you. I must remember to get a better axe.'

Allday grinned. 'My pleasure, Captain.' He strode out to fetch another chest.

Bolitho pulled the heavy sealed envelope towards him. With some education behind him Allday might have become almost anything. He slit open the envelope and smiled to himself. Without it he was quite bad enough.

Herrick stepped into the cabin, his hat tucked under one arm. `You sent for me, sir?'

Bolitho was standing by the great stern windows, his body moving easily with the ship's motion. Undine had swung her stern to the change of tide, and through the thick glass Herrick could see the distant lights of Portsmouth Point, glimmering and changing shape through the droplets of rain and spray. In the pitching deckhead lanterns the cabin looked snug and inviting. The bench seat around the stern was covered with fine green leather, and Bolitho's desk and chairs stood out against the deck covering of black and white checked canvas like ripe chestnut.

`Sit down, Thomas.'

Bolitho turned slowly and looked at him. He had been back aboard for over an hour, reading and re-reading his orders to ensure he would miss nothing.

He added, `We will weigh tomorrow afternoon. I have a warrant in my orders which entitles me to accept "volunteers" from the convict hulks in Portsmouth. I would be obliged if you would attend to that as soon after first light as is convenient..'

Herrick nodded, watching Bolitho's grave features, noting the restless movements of his hands, the fact that his carefully prepared meal lay untouched in the adjoining dining space. He was troubled. Uncertain about something.

Bolitho said, `We are to sail for Teneriffe.' He saw Herrick stiffen and added quietly, `I know, Thomas. You are like me. It comes hard to tack freely into a port where months back we could have expected a somewhat different welcome.'

Herrick grinned. `Heated shot, no doubt.'

`There. we will embark two, maybe three passengers. After replenishing whatever stores we lack, we will proceed without further delay to our destination, Madras.' He seemed to be musing aloud. `Over twelve thousand miles. Long enough to get to know one another. And our ship. The orders state that we will proceed with all haste. For that reason we must ensure our people learn their work well. I want no delays because of carelessness or unnecessary damage to canvas and rigging.'

Herrick rubbed his chin. `A long haul.'

`Aye, Thomas. A hundred days. That is what I intend.' He smiled, the gravity fading instantly. `With your help, of course.'

Herrick nodded. `May I ask what we are expected to accomplish?'

Bolitho looked down at the folded sheets of his orders. `I still know very little. But I have read quite a lot between the lines.'

He began to pace from side to side, his shadow moving unevenly with the roll of the hull.

`When the war ended, Thomas, it was necessary to make. concessions. To restore a balance. We had captured Trincomalee in Ceylon from the Dutch. The finest naval harbour and the best placed in the Indian Ocean. The French admiral, Suffren, captured it from us, and when war ended gave it back to Holland. We have returned many West Indian islands to France, as well as her Indian stations. And Spain, well, she has been given back Minorca.' He shrugged. `Many men on both sides died for nothing, it seems.'

Herrick sounded confused. `But what of us, sir? Did we get nothing out of all this?'

Bolitho smiled. `I believe we are about to do so. Hence the extreme secrecy and our vague orders concerning Teneriffe.'

He paused and looked down at the stocky lieutenant.

`Without Trincomalee we are in the same position as before the war. We still need a good harbour for our ships. A base to control a wide area. A stepping-stone to expand the East Indies trade.'

Herrick grunted. `I'd have thought the East India Company had got all it wanted.'

Bolitho's mind returned to the men on the coach. Others he had met in London.

`There are those in authority who see power as the essential foundation of national superiority. Commercial wealth as a means to such power.' He glanced at a twelve-pounder gun at the forward end of his cabin, its squat outline masked by a chintz cover. `And war as the means to all three.'

Herrick bit his lip. `And we are to be the "probe", so to speak ?'

`I may be quite wrong, Thomas. But you must know my thinking. Just in case things go against us.'

He remembered Winslade's words at the Admiralty. The task I anm giving yon would be better handled by a squadron. He wanted someone he could trust. Or did he merely need a scapegoat should things go wrong? Bolitho had always complained bitterly about being tied to too strict orders. His new ones were so vague that he felt even more restricted. Only one thing was clear. He would take on board a Mr. James Raymond at Teneriffe, and place the ship at his disposal. Raymond was a trusted government courier, and would be carrying the latest despatches to Madras.

Herrick remarked, `It will take some getting used to. But being at sea again in a ship such as Undine will make a world of difference.'

Bolitho nodded. `We must ensure that our people are prepared for anything, peace or no peace. Where we are going they may be less inclined to accept our views without argument.'

He sat down on the bench and stared through the spattered glass.

`I will speak with the other officers at eight bells tomorrow while you are in the hulks.' He smiled at Herrick's reflection. `I am sending you because you will understand. You'll not frighten them all to death!'

He stood up quickly.

`Now, Thomas, we will take a glass of claret.'

Herrick leaned forward. `That was a goodly selection you had sent from London, sir.'

Bolitho shook his head. `We will save that for more trying times.' He lifted a decanter from its rack. `This is more usual to our tastes!'

They drank their claret in comfortable silence. Bolitho was thinking how strange it was to be sitting quietly when the voyage which lay ahead demanded so much of all of them. But it was useless to prowl about the decks or poke into stores and spirit rooms. Undine was ready for sea. As ready as she could ever be. He thought of his officers, the extensions of his ideas and authority. He knew little of any of them. Soames was a competent seaman, but was inclinded to harshness when things did not go right immediately. His superior, Davy, was harder to know. Outwardly cool and unruffled, he had a ruthless streak like many of his kind. The sailing master was called Ezekiel Mudge, a broad lump of a man who looked old enough to be his grandfather. In fact he `vas sixty, and certainly the oldest master Bolitho had met. Old Mudge would prove to be one of the most important when they reached the Indian Ocean. He had originally served in the East India Company, and had endured more storms, shipwrecks, pirates and a dozen other hazards than any man alive, if his record was to be believed. He had a huge beaked nose, with the eyes perched on either side of it like tiny, bright stones. A formidable person, and one who would be watching his captain's seamanship for flaws, Bolitho was certain of that.

The three midshipmen seemed fairly average. Penn was the youngest, and had come aboard three days after his twelfth birthday. Keen and Armitage were both seventeen, but whereas the former showed the same elegant carelessness as Lieutenant Davy, Armitage appeared to be forever looking over his shoulder. A mother's boy. Four days after he had reported aboard with his gleaming new uniform and polished dirk his mother had in fact come to Portsmouth to visit him. Her husband was a man of some influence, and she had swept into the dockyard in a beautiful carriage like some visiting duchess.

Bolitho had greeted her briefly and allowed her to meet Armitage in the seclusion of the wardroom. If she had seen the actual quarters where her child was to serve his months at sea she would probably have collapsed.

He had had to send Herrick in the end to interrupt the embraces and the mother's plaintive sobs with a feeble excuse about Armitage being required for duty. Duty; he could hardly move abous the ship without falling headlong over a block or a ringbolt.

Giles Bellairs, the debonair captain of marines, was more like a caricature than a real person. Incredibly smart, shoulders always rigidly squared, he looked as if he had had his uniforms moulded around his limbs like wax. He spoke in short, clipped sentences, and barely extended much beyond matters of hunting, wildfowling and, of course, drill. His marines were his whole life, although he hardly ever seemed to utter much in the way of orders. His massive sergeant, Coaker, took care of the close contact with the marines, and Bellairs contented himself with an occasional `Carry on, Sar'nt Coaker!' or `I say, Sar'nt, that fellah's like a bundle of old rags, what?' He was one of the few people in Bolitho's experience who could get completely drunk without any outward change of expression.

Triphook, the purser, appeared very competent, if grudging with his rations. He had taken a lot of care to ensure that the victualling yard had not filled the lower hold with rotten casks, to be discovered too late to take action. That in itself was rare.

Bolitho's thoughts came back to the surgeon. He had been aboard for two weeks. Had he been able to get a replacement he would have done so. Whitmarsh was a drunkard in the worst sense. Sober he had a quiet, even gentle manner. Drunk, which was often, he seemed to come apart like an old sail in a sudden squall.

He tightened his jaw. Whitmarsh would mend his ways. Or else....

Feet scraped across the planks overhead and Herrick said, `There's a few below decks tonight who'll be wondering if they've done a'right by signing on.' He chuckled. `Too late now.'

Bolitho stared astern at the black, swirling water, hearing the urgent tide banging and squeaking around the rudder.

`Aye. It's a long step from land to sea. Far more so than most people realise.' He returned his glass to the rack. `I think I shall turn in now. It will be a long day tomorrow.'

Herrick stood up and nodded. `I'll bid you goodnight, sir.'

He knew full well that Bolitho would stay awake for hours yet. Pacing and planning, searching for last-minute faults, possible mistakes in the arrangement of watch-bills and delegation of duties. Bolitho would know he was aware of this fact, too.

The door closed and Bolitho walked right aft to lean his hands on the centre sill. He could feel the woodwork vibrating under his palms, the hull trembling all around him in time to the squeak of stays, the clatter and slap of halliards and blocks.

Who would watch them go? Would anyone care? One more ship slipping down channel like hundreds before her.

There was a nervous tap at the door, and Noddall, the cabin servant, pattered into the lantern light. A small man, with the pointed face of an anxious rodent. He even held his hands in front of him like two nervous paws.

'Yer supper, sir. You've not touched it.' He started to gather up the plates. `Won't do, sir. It won't do.'

Bolitho smiled as Noddall scampered away to his pantry. He was so absorbed in his own little world it seemed as if he had not even noticed there was a change of command.

He threw his new cloak across his shoulders and left the cabin. On the pitch-dark quarterdeck he groped his way aft to the taffrail and stared towards the land. Countless lights and hidden houses. He turned and looked along his ship, the wind blowing his hair across his face, the chill making him hold his breath. The riding light reflected on the taut shrouds like pale gold, and right forward he saw a smaller lantern, where the lonely anchor watch kept a wary eye on the cable.

It felt different, he decided. No sentries on each gangway to watch for a sneak attack or a mass attempt at desertion. No nets to delay a sudden rush of enemy boarders. He touched a quarterdeck six-pounder with one hand. It felt like wet ice. But for how long, he wondered?

The master's mate of the watch prowled past, and then sheered away as he saw his captain by the rail.

`All's well, zur!' he called.

`Thank you.'

Bolitho did not know the man's name. Not yet. In the next hundred days he would know more than their names, he thought. As they would about him.

With a sigh he returned to his cabin, his hair plastered to his head, his cheeks tingling from the cold. There was no sign of Noddall, but the cot was ready for him, and there was something hot in a mug nearby.

A minute after his head was or. the pillow he was fast asleep.

The next day dawned as grey as the one before, but overnight the rain had stopped, and the wind held firm from the southeast.

All forenoon the work went on without relaxation, the petty officers checking and re-checking their lists of names, putting them to faces, making sure seasoned hands were spaced among the untried and untrained.

Bolitho dictated a final report to his clerk, a dried-up man named Pope, and then signed it in readiness for the last boat. He found time to speak with his officers, and seek out Mr. Tapril, the gunner, in his magazine to discuss moving some of the spare gun parts and tackle further aft and help adjust the vessel's trim until she had consumed some of her own stores to compensate for it.

He was changing into his seagoing coat, with its faded lace and dull buttons, when Herrick entered the cabin and reported he had brought fifteen new man from the hulks.

`What was it like?'

Herrick sighed. `It was a sort of hell, sir. I could have got treble the number, a whole company of 'em, if I'd been able to bring their women and wives, too.'

Bolitho paused as he tied his neckcloth. `Women? In the hulks?'

`Aye, sir.' I-Ierrick shuddered. `I hope I never see the like again.'

`Very well. Sign them on, but don't give them anything to do just yet. I doubt they've the strength to lift a marlin spike after being penned up like that.'

A midshipman appeared in the open door.

`Mr. Davy's respect, sir.' His eyes darted around the cabin,

missing nothing. `And the anchor's hove short.'

`Thank you.' Bolitho smiled. `Next time stay awhile, Mr.

Penn, and have a better look.'

The boy vanished, and Bolitho looked steadily at Herrick. `Well, Thomas?'

Herrick nodded firmly. `Aye, sir. I'm ready. It's been a long wait.'

They climbed up to the quarterdeck together, and while Herrick moved to the forward rail with his speaking trumpet, Bolitho stood aft, a little apart from the others who were gathered restlessly at their stations.

Clink, clink, clink, the capstan was turning more slowly now, the men's backs bent almost double as the hull pulled heavilyy on the anchor.

Bolitho looked at the master's untidy shape beside the double wheel. He had four helmsmen. He was taking no chances, it seemed. With the helm, or his new captain's skill.

`Get the ship under way, if you please.' He saw Herrick's trumpet moving. `Once clear of this local shipping we will lay her on the larboard tack and steer sou'-west by west.'

Old Mudge nodded heavily, one eye hidden beyond the headland of a nose.

`Aye, aye, sir.'

Herrick yelled, `Stand by on the capstan!' He shaded his eyes to peer up at the masthead pendant. `Loose heads'ls!'

The answering flap and clatter of released canvas made several new men peer round, confused and startled. A petty officer thrust a line into a man's hand and bellowed, ''Old it, you bugger! Don't stand there like a bloody woman!'

Bolitho saw a bosun's mate right forward astride the bowsprit, one arm circling above his head as the cable grew stiffer and more vertical beneath the gilded water-nymph.

`Hands aloft! Loose tops'ls!'

Bolitho relaxed slightly as the nimble-footed topmen swarmed up the ratlines on either beam. No sense in rushing it this first time. The watching eyes ashore could think what they liked. He'd get no thanks for letting her drive ashore.

`Man the braces!'

Herrick was hanging over the rail, his trumpet moving from side to side like a coachman's blunderbuss.

`Lively there! Mr. Shellabeer, get those damned idlers aft on the double, I say!'

Shellabeer was the boatswain, a swarthy, taciturn man who looked more like a Spaniard than a Devonian.

Bolitho leaned back, his hands on his hips, watching the swift figures dashing out on the vibrating yards like monkeys. It made him feel sick to watch their indifference to such heights.

First one, then the next great topsail billowed and banged loosely in confusion, while the seamen on the yards clung on, calling to each other, or jeering at their opposite numbers on the other masts.

`Anchor's aweigh, sir!'

Like a thing released from chains the frigate swung dizzily across the steep troughs, men falling and slithering at the braces as they fought to haul the great yards round, to cup the wind and master it.

`Lee braces there! Heave away!' Herrick was hoarse.

Bolitho gritted his teeth and forced himself to remain quite still as she plunged further and further astride the wind. Here and there a bosun's mate struck out with his rope starter or pushed a man bodily to brace or halliard.

Then with a booming roar like thunder the sails filled and hardened to the wind's steady thrust, the deck canting over and holding steady as the helmsmen threw themselves on their spokes. -

He made himself take a glass from Midshipman Keen and trained it across the starboard quarter, keeping his face impassive, even though he was almost shaking with excitement and relief.

The sail drill was very bad, the placing of trained men too sketchy for comfort, but they were away! Free of the land.

He saw a few people on the Point watching them heel over on the larboard tack, the top of a shining carriage just below the wall. Perhaps it was Armitage's mother, weeping as she watched her offspring being taken from her.

The master shouted gruffly, 'Sou'-west by west, sir! Full an' bye !'

When Bolitho turned to answer him he saw that the master was nodding with something like approval.

`Thank you, Mr. Mudge. We will get the courses on her directly.'

He walked forward to join Herrick at the rail, his body angled steeply to the deck. Some of the confusion was being cleared, with men picking their way amidst loose coils of rope like survivors from a battle.

Herrick looked at him sadly. `It was terrible, sir.'

`I agree, Mr. Herrick.' He could not restrain a smile. `But it will improve, eh?'

By late afternoon Undine had beaten clear of the Isle of Wight and was standing well out in the Channel.

By evening only her reefed topsails were visible, and soon even they had disappeared.

On the morning of the fourteenth day after weighing anchor at Spithead Bolitho was in his cabin sipping a mug of coffee and pondering for the countless time on what he had achieved.

The previous evening they had sighted the dull hump of Teneriffe sprawled like a cloud across the horizon, and he had decided to heave-to and avoid the hazards of a night approach. Fourteen days. It felt an eternity. They had been plagued by foul weather for much of that time. Flicking over the pages of his personal log he could see the countless, frustrating entries. Headwinds, occasional but fierce gales, and the constant need to shorten sail, to reef down and ride it out as best they could. The dreaded Bay of Biscay had been kind to them, that at least was a mercy. Otherwise, with almost half the ship's company too seasick to venture aloft, or too terrified to scramble out along the dizzily pitching yards without physical violence being used on them, it was likely Undine might have reached no further.

Bolitho appreciated what it must be like for many of his men. Shrieking winds, overcrowded conditions in a creaking, rolling hull where their food, if they could face it, often ended up in a mess of bilge water and vomit. It produced a kind of numbness, like that given to a man left abandoned in the sea. For a while he strikes out bravely, swimming he knows not where, until he is too exhausted, too dazed to care. He is without authority or any sort of guidance. It is his turning point.

Bolitho recognised all the signs well enough, and knew it was the same sort of challenge for him. Give in to his own underStanding and sympathy, listen too much to excuses from his hard-worked lieutenants and warrant officers, and he would never regain control, or be able to rally his company when the real pressure came.

He knew that many cursed him behind his back, prayed for him to fall dead or vanish overboard in the night. He saw their glances, sensed their resentment as he pushed them through each day, each hour of every one of those days. Sail drill, and more drill against Herrick's watch, while he himself made sure all engaged knew he was following their efforts. He made the men on Undine's three masts race each other in their struggle to shorten or make more sail, until finally he drove them even harder to work not in competition but as a gasping, silently cursing team.

Now, as he sat with the mug in his hands he found some grudging satisfaction in what they had done. What they had achieved together, willingly or otherwise. When Undine dropped her anchor in the roads of Santa Cruz today, the watching Spaniards would see a semblance of order and discipline, of efficiency which they had come to know and fear in times of war.

But if he had driven his company to the limit he had not spared himself either. And he was feeling it, despite the inviting rays of early sunshine which made reflections dance across the low deckhead. Barely a watch had passed without his going on deck to lend his presence. Lieutenant Davy had little experience of handling a ship in foul weather, but would learn, given time. Soames was too prone to lose patience when faced with a disaster on deck. He would knock some luckless seaman aside and leap into his place yelling, `You're useless! I'd rather do it myself!' Only Herrick rode out the storm of Bolitho's persistent demands, and Bolitho felt sorry that his friend had been made to carry the brunt of the work. It was too easy to punish men, when in fact it was an officer's fault for losing his own head, or not being able to find the right words in the teeth of a raging gale. Herrick stood firmly between wardroom and lower deck, and twixt captain and company.

There had even been two floggings, something which he had hoped to avoid. Each case had been within the private world of the lower deck. The first a simple one of stealing from another sailor's small hoard of money. The second, far more serious, had been a savage knife-fight which had ended in a man having his face opened from ear to jaw. It was still not certain if he would live.

A real grudge fight, a momentary spark of anger caused by fatigue and constant work, he did not really know. In a welltrained ship of war it was likely he would never have heard about either case. The justice of the lower deck was far more drastic and instant when their own world was threatened by a thief or one too fond of his knife.

Bolitho despised captains who used authority without consideration for the misery it might entail, who meted out savage punishment without getting to the root of the trouble and thereby avoiding it. Herrick knew how he felt. When Bolitho had first met him he had been the junior lieutenant in his ship. A ship where the previous captain had been so severe, so unthinkingly brutal with his punishments that the seeds of mutiny had been well and truly laid.

Herrick knew better than most about such things, and yet he had intervened personally to persuade Bolitho to avoid the floggings. It was their first real disagreement, and Bolitho had hated to see the sudden hurt in Herrick's eyes.

Bolitho had said, `This is a new company. It takes time to weld people together so that each can rely on his companion under all circumstances. Many are entirely ignorant of the Navy's ways and its demands. They hate to see "others" getting away with crimes they themselves avoid. At this stage we cannot allow them to split into separate groups. Old hands and the new recruits, professional criminals and the weak ones who have no protection but to ally themselves with some other faction.'

Herrick had persisted, `But in peacetime, sir, maybe it takes all the longer.'

`We can't afford the luxury of finding out.' He had hardened his voice. `You know how I feel. It is not easy.'

The thief had taken his punishment without a whimper, a dozen lashes at the gratings while Undine had cruised along beneath a clearing sky, some gulls throwing their shadows round and round across the tense drama below.

As he had read from the Articles of War, Bolitho had looked along his command at the watching men in shrouds and rigging, the sharp red lines of Bellairs' marines, Herrick and all the rest. The second culprit had been a brute of a man called Sullivan. He had volunteered to a recruiting party outside Portsmouth, and had all the looks of a hardened criminal_ But he had served in a King's ship before and should have been an asset.

Three dozen lashes. Little enough in the Navy's view for half killing a fellow seaman. Had he laid a hand on an officer he would have faced death rather than a flogging.

The actual punishment was terrible. Sullivan had broken down completely at the first blow across his naked back, and as the boatswain's mates took turns to lay the lash over his shoulders and spine he had wriggled and screamed like a madman, his mouth frothing with foam, his eyes like marbles in his distorted face.

Mr. Midshipman Armitage had almost fainted, and some of those who had just recovered from their own sickness had vomited in unison, despite the harsh shouts from their petty officers.

Then it had ended, the watching men giving a kind of sigh as they were dismissed below.

Sullivan had been cut down and carried to Whitmarsh's sickbay, where no doubt he had been restored by a plentiful ration of rum.

Each day following the punishment, as he had paced the quarterdeck or supervised a change of tack, Bolitho had felt the eyes watching him. Seeing him perhaps as enemy rather than commander. He had told himself often enough that when you accepted the honour of command you carried all of it. Not just the authority and the pride of controlling a living, vital ship, but the knocks and kicks as well.

There was a tap on the door and Herrick stepped into the cabin.

`About another hour, sir. With your permission I will give the order to clew up all canvas except tops'ls and jib. It will make our entrance more easy to manage.'

`Have some coffee, Thomas.' He relaxed as Herrick seated himself across the table. `I am burning to know what we are about.'

Herrick took a mug and tested the coffee with his tongue.

`Me, too.' He smiled over the rim. `Once or twice back there I thought we might never reach land!'

`Yes. I can feel for many of our people. Some will never have seen the sea, let alone driver. so far from England. Now, they know that Africa lies somewhere over the larboard bulwark. That we are going to the other side of the earth. Some are even beginning to feel like seamen, when just weeks back they had thumbs where their fingers should be.'

Herrick's smile widened. `Due to you, sir. I am sometimes very thankful that I hold no command. Or chance of one either.'

Bolitho watched him thoughtfully. The rift was healed.

`I am afraid the choice may not be yours, Thomas.' He stood up. `In fact, I shall see that you get command whenever the opportunity offers itself, if only to drive some of your wild idealism into the bilges !'

They grinned at each other like conspirators.

`Now be off with you while I change into a better coat.' He grimaced. `To show our Spanish friends some respect, eh?

A little over an hour later, gliding above her own reflection, Undine moved slowly towards the anchorage in the roads. In the bright sunlight the island of Teneriffe seemed to abound with colour, and Bolitho heard several of the watching seamen gasping with awe. The hills were no longer hidden in shadow, but danced on the glare with every shade and hue. And everything was brighter and larger, at least it appeared so to the new hands. Shimmering white buildings, brilliant blue sea, with beaches and surf to make a man catch his breath and stare.

Allday stood aft by the cabin hatch and remarked, `I'll bet some Don'd like to rake us as we come by!'

Bolitho ran his eye quickly along his ship, trying to see her as those ashore would. She looked very smart, and gave little hint of the sweat and effort which had gone to make her so. The best ensign fluttered from the gaff, the scarlet matching that of the marines' swaying lines athwart the quarterdeck. On the larboard gangway Tapril, the gunner, was having a last hurried discussion with his mates in readiness to begin a salute to the Spanish flag which flew so proudly above the headland battery.