Alan Burt Akers has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work.

First published by Daw Books, Inc. in 1975.

This Edition published in 2006 by Mushroom eBooks, an imprint of Mushroom Publishing, Bath, BA1

4EB, United Kingdom

www.mushroom-ebooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1843193965

Bladesman of Antares

Alan Burt Akers

Mushroom eBooks

Foreword

DRAY PRESCOT

Dray Prescot is a man above medium height, with straight brown hair, and brown eyes that are level and dominating. His shoulders are immensely wide and there is about him an abrasive honesty and a fearless courage. He moves like a great hunting cat, quiet and deadly. Born in 1775 and educated in the inhumanly harsh conditions of the late eighteenth-century English Navy, he presents a picture of himself that, the more we learn of him, grows no less enigmatic.

Through the machinations of the Savanti nal Aphrasöe — mortal but superhuman men dedicated to the aid of humanity — and of the Star Lords, he has been taken to Kregen under the Suns of Scorpio many times. On that savage and beautiful, marvelous and terrible world he rose to become Zorcander of the Clansmen of Segesthes, and Lord of Strombor in Zenicce, and a member of the mystic and martial Order of Krozairs of Zy.

Against all odds Prescot won his highest desire and in that immortal battle at The Dragon’s Bones claimed his Delia, Delia of Delphond, Delia of the Blue Mountains. And Delia claimed him in the face of her father the dread Emperor of Vallia. Amid the rolling thunder of the acclamations of Hai Jikai! Prescot became Prince Majister of Vallia, and wed his Delia, the Princess Majestrix. One of their favorite homes is in Valkanium, capital of the island of Valka, of which Prescot is Strom. Through the agency of the blue radiance sent by the Star Lords, the Summons of the Scorpion, Prescot is plunged headlong into fresh adventures on Kregen in the continent of Havilfar. Outwitting the Manhounds of Antares and fighting as a hyr-kaidur in the arena of the Jikhorkdun in Huringa in Hyrklana, he becomes King of Djanduin, idolized by his incredibly ferocious four-armed warrior Djangs. But Hamal, the greatest power in Havilfar, is bent on conquest, and Prescot has slaved in their diabolical Heavenly Mines. Now, his mission is to discover the secrets of the Hamalese airboats for his own people

. . .

Alan Burt Akers

Chapter One

Into Hamal

All my thoughts centered on Hamal. There, in that progressive and yet violently barbaric country, I felt confident that the secrets of the marvelous airboats of Havilfar were to be discovered. And if I, Dray Prescot, of Earth and of Kregen, did not quickly guide this little flier out of the gale hurling me about the sky like a dead leaf, I was likely to discover the biggest secret in two worlds. Wind-driven rain razored against my face over the smashed windscreen. Rain soaked my hair and face and stung into my eyes. The little flier stood on her nose, dived, swooped sickeningly, flew upward, spun about like a child’s kicked top. I clung on, hoping to Zair the leather straps would stand the strain and not snap, to send me pitching into the hard ground beneath.

The darkness of the darkest of nights hung about me, and yet somewhere high above, the twin suns of Antares were flooding down their rich ruby-and-emerald fires. I dashed water from my face, and cursed, and thrust uselessly at the control levers. The flier did not respond. This was not the swift racing voller I had taken from Sumbakir, where she had been built. With my natural greed I had left that superb craft back home in Valka and had instead taken an ordinary little Hamalese flier, which had seen much use. My frugality was likely to cost me dear. With a shocked oath I ripped instinctively at the controls as from the gloom ahead a wide-branched tree whirled toward me. The tree appeared instantaneously from the murk and as suddenly was gone. The craft spun end over end above the tree. I felt the gonging blows of branches as they battered the canvas-skinned wooden frame. A rough-barked branch punched through and beat at my leg before that mad onward movement wrenched the branch free in a weltering sound of ripping canvas. Everything was streaming water, everything was in violent motion, everything was going up and down; the world spun dizzily about me — that wonderful if terrible world of Kregen, four hundred light-years from the planet of my birth.

In some fashion or other I had to land. More trees flashed past, their gray arms reaching out to destroy my frail craft. I peered ahead, drenched by rain and buffeted by wind, half deafened by the racket. At any minute I was likely to get myself killed and packed off to the Ice Floes of Sicce. There were certain things I must do before that happened, which, in the ordinary course of events, should happen in a thousand years or so.

“By Zair!” I shouted, and thumped the useless controls. “Go down, you onker!”

End over end the flier whirled from the darkness. Rain fell for a space, and then cleared, and I was blinking in doubled sunshine. A swift look to my rear showed the malevolent stormclouds boiling blackly as they poured over the land, darkening the greens and yellows below. I was low, perilously low. A circling gust had cast me from the main path of the storm. But the controls would not answer and the flier roared on, driven by the breeze, for she was of that build which is susceptible to winds. I looked ahead. The land spread flat before me, ocher and dun, with scattered clumps of trees, threaded by the sparkle of narrow watercourses. This was grazing land, I considered, and to confirm that observation I saw herds of animals, running. Far on the horizon lifted a range of mountains, glittering under the opaz fire of the suns. These, if my navigation had been correct, were the Mountains of the West of Hamal. I was heading due south, having come over the sea from Valka and penetrating well into the country down the hook-shaped expanse of water of Skull Bay. I’d never lift over those sharp fangs. This little voller would be driven directly onto the rocks. The gale had let me slip from its clutches, but I was still in danger. The flier remained now on an even keel, but as the wind pushed her, so she swung and drifted aimlessly. This would not do. I had come to this strange country of Hamal to discover what I needed to know about fliers so that my own country of Vallia might construct reliable models. The irony of the situation was not lost on me. Here I was, scheming to obtain the secrets of the vollers, being thwarted and threatened for my life by the very Opaz-forsaken monstrosity I wished to discover!

The crystalline glitter in the air with its mingling of streaming colors from the twin suns of Antares that, on a fine day, should be bottled up and shipped to Earth to banish all the fug and despondency — and to make the shipper a fortune — darkened again with sudden and ominous power. A swirling arm of the storm, wind-driven, black and boiling, swooped up abaft of me and in seconds I was once again enveloped in gloom.

The flier pitched about, corklike, and I knew that beneath now the keel, now the stem, now the ripped canvas decking, the ground streamed past, ready to shatter both my craft and me. This second tempestuous whirlwind howled past with maniacal force and rushed away ahead, leaving the flier to be sucked along limping in its wake.

The blackness ahead covered the land.

Rain had formed into torrential rivulets that joined and broadened and foamed in cataracts into the narrow streams. I saw herds of animals rushing in frenzy, their long horns an upthrust and savage forest of spears.

The ground rushed up.

I gave a last frantic belting to the control levers. To this day I do not know if my hammering made the difference, whether something freed itself in the mechanism, whether some other movement helped; but, for whatever cause, the nose of the voller lifted. For agonizing seconds I hung, still going down, still aimed to smash headlong into the earth. The stem rose a little more as I bashed the levers again and we were rising, and the ground sped past below, so close I could smell the scent of fresh rain upon dust. The voller rose and flew straight.

Maybe it was the merciless bashing I gave the controls; I do not think it was from any actions of the Star Lords or the Savanti.

The mountains were now much closer, the storm coalescing into weird black shapes as the clouds roiled against the rock faces. A column of black smoke attracted my attention, and a single look convinced me I was witnessing an all too familiar sight on many parts of Kregen. The world is beautiful and wonderful; it is also dark and terrible, and I have had my fair share of the vaol-paol — the end and the beginning, the light and the dark.

Delia had insisted I pack so much gear aboard the flier that I had teased her I would have no space for myself. And she had replied, unsmiling, that perhaps that would be a better idea than this insane, impulsive journey to Hamal to discover the secrets of their fliers . . . I took up the spyglass and clapped it to my eye, and with that old familiar, unthinking seaman’s instincts swaying the telescope with the swayings of my craft, I spied out the mischief ahead.

Well, it was no business of mine.

That was the first thought that crossed my mind.

Down below, still smoking after the drenching it must have taken from the rain squall, a village burned. Here in the northwest of Hamal, in this forgotten tongue of land that stretches between the southern end of Skull Bay and the westerly curve of the Mountains of the West, they build villages snugly. The dense tropical jungles lie to the north. Farther south the land is parched. Here is good grazing land. The houses of the village were built with their backs facing outward, in an oval formation. Their front doors opened onto the village square, and the well, and the shade trees, and the busy life of the community. One or two houses were of three stories, higher than the rest. But they were all burning. As I approached, I judged the walls to be mud brick; the roofs must have been of thatch, or leaves, for they had completely disappeared. Cow dung makes a useful roof. A number of people were running about, and it seemed to me they ran aimlessly.

No business of mine.

Even when the flutsmen rose into view, urging their fluttrells away from the smoke and down onto the frightened people, I still said it was no business of mine.

The flutsmen, as you know, are the mercenaries of the skies; mounted on their flying steeds, they hire themselves out to any who will pay the high cost of their employment. I guessed that this bunch had been hired by aragorn, slave-masters, to round up a fresh batch of slaves. I do not care for slave-masters.

I have not much time for slavers.

I would, given the circumstances, as lief split an aragorn in half as give him the time of day. Old customs die hard. Many men professing faith, men of integrity, can make out a good case for slavery. One useful test to put to them is to suggest that they take a turn at slavery themselves, put on the torque, the chains, the thongs, the yoked stick, carry out hard and unrewarding tasks with a beating for wages. I believe they might then suffer a change of heart, that if they were slaves they would see the old custom in a new light.

But . . . this was not my business.

I had not been bidden here by the Star Lords to save anyone from a cruel fate, so I needn’t fear their punishment for failing that task — to be thrust back to Earth, four hundred light-years away. I was a free agent. The decisions were mine. In this matter I was not a puppet.

Like old customs, old habits die hard.

I took up the great Lohvian longbow given to me by Seg Segutorio, who had himself built it with loving care, built it as only a master bowman of Erthyrdrin can build a longbow. I had practiced with this bow, and I knew her ways. I could split the chunkrah’s eye at unbelievable ranges. Each arrow had been manufactured under the intolerant eye of Seg. Each shaft was true, as near the others in weight and balance and size as any skill could make it by hand, without the standardization of mass production. Each shaft was fletched with the brilliant blue feathers of the king korf. Each head was of tempered Kregan steel, for Seg would acknowledge that high-quality steel did, indeed, possess advantages over his well-tried flint. There were heads for different purposes: wide-cutting flesh-slicers, narrow and heavy bone-smashers, thin bodkins for deep penetration, even a few blunted shafts for bird-ratching. I eyed the flutsmen.

So absorbed were they in their evil work they did not see the silent approach of my flier. Their fluttrells curved against the sky, swooping down. Ropes flew, barbed with cunning iron, and snagged screaming fugitives, upending them, dragging them through the dust.

The flutsmen had set the place afire, but the rain squall had swirled upon them, and now they were busy trying to bring their slaving activities back to the order I guessed they usually experienced. The rain had given the village a chance. I frowned. I could see no resistance. With a chance . . . surely there were men below with weapons, men who would fight for their women and children, for their own lives and liberty. The shafts were set before me, arrayed in their quick-draw sleeves along the rim of the voller. I took the first shaft between the fingers of my right hand.

This was no business of mine.

I should let the wind drive my craft on, past the burning village, past the flutsmen, past the shrieking people. If I was killed here, what good would that do my Delia, my Delia of Delphond, my Delia of the Blue Mountains? How would that give the protection I owed to my young twins, Drak and Lela? How would my death here bring the prosperity I so urgently desired to my people of Valka and of Strombor, of Djanduin, and of the clansmen of Felschraung and Longuelm?

At last I saw the foolishness of the question, for those wild clansmen are so perfectly capable of taking care of themselves, there on the limitless expanses of the Great Plains of Segesthes, and with Hap Loder to chivy them along when necessary, that I could, and did, Zair forgive me, leave them to their own rascally devices for seasons at a time.

No, with or without the Star Lords, with or without the Savanti, with or without all the duties I owed my people, this petty slaving affray below was no business of mine.

So I took up the first shaft, notched it, drew back the string, and loosed. The shaft took the nearest flutsman under the ear.

He pitched from his saddle, hanging from the clerketer, the straps beating in the wind as his mount reared aloft.

The next shaft dispatched a flutsman whose swung line had barbed a man, who simply sprawled forward, his hands clasped together, his body limp.

Then it was a matter of shooting as fast as I might haul the shafts from their sleeves around the rim of the voller, of drawing the string and of loosing. Shaft after shaft sped; I think only two missed their mark. Now the slavers could not fail to take notice of me.

Standing braced as I was in the tiny forward compartment, I must have presented a target to them they considered easy, a mere man to be swept away with a swift attack and a shower of stuxes. They hurled their javelins, true enough. But I snatched up a shield and hung it on my left shoulder. This was a trick I had been practicing, to the enormous amusement of Seg and my other friends in Valka, and, I admit, to the worried annoyance of Turko the Shield. Stuxes banged and slithered against the shield. I could still shoot. If a javelin was launched at my right side — and be very sure I kept a sharp lookout to starboard

— I could duck or sway away from its flight. Only three times had I to release the string of the longbow and so reach out and pluck the flying javelin from the air. These three went back whence they came, to bury their broad heads deeply into the bodies of their late owners.

Fluttrell wings blattered the air about me. Stuxes flew. Now the enraged flutsmen swooped in, closer and closer, and they tried to stick me with their long lance-swords. The blades sliced and slashed, and chunks of the voller’s wooden frame splintered and strips of the canvas cover ripped away. I let the great Lohvian longbow slide to the deck.

The feel of the longsword in my hands, as always, gave me that uplifting and yet fallible feeling I have so often described. With the naked brand in my fists I prepared to deal blow for blow. This longsword was a true longsword. It was not a Krozair longsword. But it was as close as I could make it in the smithy at home in the high fortress of Esser Rarioch overlooking Valkanium. Naghan the Gnat, the cunning armorer, and I, with the best swordsmiths I could find, had labored long to produce this weapon. I had debated whether or not to bring that true Krozair longsword with me but — for the same reasons I had brought this inferior flier, the same reason I wore a sober gray shirt and blue trousers over the old scarlet breechclout — I had decided not to bring that marvelous brand with the letters KRZY

incised on the blade.

Naghan the Gnat had proved a first-class armorer and swordsmith. Together we had folded and refolded the glowing metal, producing that cunning interlay of many thicknesses demanded of a true blade. With varying thicknesses of clay during the annealing process we had developed a diamond-hard cutting edge from the point up both edges, and that more tough and flexible central spine. We had labored amid heat and smoke and sweat to fashion this blade. It was as true a longsword as might be found outside the Eye of the World; but, even so, it still was not a Krozair longsword. But, here, in an affray with miserable aragorn-hired flutsmen, it would serve to lop a few heads, to dismember, to rip the smoking guts out of these evil slavers.

The feel of the silver-wire-wound hilt was all I needed to go to work. And then, in that moment when, with the blood singing through my veins and the beginnings of a juicy little encounter shaping up, I fancied I might discommode these cramphs, the flier jerked, yawed, flummoxed in the air, and then plunged straight for the ground.

In a matter of moments my flier would smash headlong into the earth and smash me along with it.

Chapter Two Flutsmen

That abrupt plunge earthward scattered the flying slavers away from the voller. Wings skittered sharply as the flutsmen veered away. One flutsman, however -— no doubt seething with anger that with all their vaunted prowess the mercenaries of the air had failed to dispose of a single flier — swooped upon me with a screech. He clearly intended to sink his long-bladed weapon into me before I struck ground. That suited me perfectly.

The intention suited me; not the execution of that design.

The ground leaped up toward me. The fluttrell barreled over, tasseled flying cloths fluttering, the straps of the clerketer holding the flutsman swinging wildly. The long lance, razor sharp, speared for my body. Where normally I would have buffeted it away with a swing of my blade, I let my body swing away. I shifted grips on the two-handed hilt of the longsword. With the sword in my left hand I braced, flexed my legs, and leaped.

For a single heartbeat I thought I had missed.

The flyer swooped down on me, the lance lashed past my side, and I sprang upward. My fingers clenched around the dangling wind-driven straps of the clerketer. I took a firm grasp and hauled up.

The fluttrell felt the extra weight come on, but a fluttrell can carry two as easily as one. His powerful talons opened for a moment where they were tucked up beneath his velvety-green body, and then, click, back they went, and with a strong beat of his beige-white wings he surged aloft. The flutsman looked down.

He was not a member of Homo sapiens. I had not previously met the particular race of diffs of which he was a member, and there was no time now to concern myself over that. Although I did have some slight interest to see if he would bleed red blood.

I started to hand myself up, straining on the straps.

The fluttrell’s large head-vane turned and the flutsman put his own head down in a perfectly instinctive way to avoid the vane, and so I got my feet into the straps and took another purchase for my fist. Again the flutsman looked over the side. From the streamlined helmet covered with velvety-green feathers the flaring, clotted mass of multicolored ribbons flicked and fluttered most bravely. He had stowed his lance-sword into its bucket and had drawn his thraxter. This was a wise move on his part, for the straight cut-and-thrust sword would be of more use to him now. I inched up another hold.

Against the wind-stream clatter he shouted down: “Apim! Crawl up to die, rast!”

I am apim, a member of Homo sapiens. A rast, as you know, is a disgusting six-legged rodent infesting dunghills. I have been called a rast many times on Kregen, and no doubt will be so called for a goodly number of times yet; so that the word meant nothing.

Since I didn’t know from what race of diffs he owed his parentage, I could not goad him with a racially pointed insult. It is my custom not to tell a foeman what I am going to do unless some good end is served. He was clearly expecting me to lift myself up to get at him, when he would incontinently take a slash at my face, hoping to finish me with one blow.

The longsword in my left fist whirled around, flat against the slipstream. The blow was judged to a nicety. The keen blade sliced his leg, cut through the bone, sliced the flesh on the other side and did not so much as touch a feather of the fluttrell.

The flutsman yelled.

While he was caterwauling away I hefted up again, took my last grip around his waist and, with a thrust from my feet, toppled him over on the opposite side.

He hung dangling, screeching. The thraxter whirled wildly from its thong to his wrist. I slashed the clerketer and watched the slaver fall to the ground.

At a much later stage of my career they had no need to tell me: “Don’t sit and watch your man flame to the ground; keep your head turning! Watch up sun!”

I kept my head turning then as I had learned long ago on Kregen. I clamped my knees to the fluttrell and urged him sideways and aloft, and I kept my head down. The flashing glimpse of mirror-bright steel whickered past as a lance-sword missed.

The longsword glimmered with blood. Without compunction I wiped it on the velvety-green feathers of the flying mount before I thrust it into the scabbard. Delia had supervised the stitching of that scabbard; I would not willingly foul her work with gore.

The situation had now taken a piquant turn.

The fluttrell with that awkward head-vane is not a favorite flying mount, in my view; but I had put my hand to a task and so must go on. The great Lohvian longbow had taken its toll of slavers. The longsword had taken more. Now I went to work with an aerial weapon, the long lance-sword of the flutsmen, so like the toonon of the Ullars of Northern Turismond. We battled there in the sky, and now I made it my business to swoop down low and so chop the flutsmen in the act of barbing potential slaves. There is a saying on Kregen that a flutsman would not walk across the road to pick up a purse of gold. Of course not; he would fly across, just as a zorcaman would ride across. But, even so, a number of these aragorn-hired mercenaries had landed and leaped off their birds to round up the slaves. Angling my wind-eater down toward them, and spearing a flutsman as he tried to stop me, I dived on them. There was no subtlety in my handling of the bird; he recognized the hands and knees and feet of a rider who knew what he wanted and knew also unpleasant ways — as well as pleasant ones — of obtaining the desired result. The fluttrell gave no trouble and I was able to wheel and guide him about the sky as though we had been in partnership for seasons of fighting.

The slavers below saw me coming and lifted their weapons.

I guided the wind-eater directly at them, swinging him low, forcing him down. And as I did so I leaned over and bellowed close alongside his head so that he could hear.

“Tchik!” I yelled at the bird. “Tchik!”

At that command the fluttrell went wild.

Down came his talons that could sink into oak.

Out they stretched, clawing, sharp, ferocious, deadly.

The flutsmen yelled and some scattered, some stood their ground, and these either died under the diabolical claws of the bird or were slashed by the lance-sword. Up and up we swooped at the end of the run. The fluttrell needed no order from me to bank on a wing and come sliding around for another pass.

When a flutsman gives that dread order to his wind-eater, “Tchik,” the monstrous bird becomes a killer. The problem, as I knew, is to bring the bird back under control again. Seldom can that be achieved while still in the air. I did not attempt it. I forced the bird down to where a group of flutsmen clustered, caught in the open and unable to run for their own mounts. Flutsmen, caught afoot!

What a moment!

They screeched as those vicious claws sank into their bodies. The lance-sword scythed into them. Back and forth my mount flew, raging, mad with killing frenzy. I kept a sharp eye aloft at the few remaining flutsmen, for I was puzzled by the fact they had not used their crossbows. Truth to tell, I had not seen any crossbows strapped to their saddles. As you know, there are crossbows and crossbows in Havilfar, and flutsmen boast of the quality of theirs. (In later seasons I experienced a whole band of these mercenaries of the skies who refused to use crossbows because they were not of the very finest manufacture. Other flutsmen disown the crossbow because of its difficulty in spanning while airborne, although you who have listened to these tapes[1]will know it is a trick that can be learned speedily enough.) Around me in the air the flutsmen raged to strike the single blow that would free them from my encumbrance, and thus allow them to get on with their rapacious plundering of human flesh. For the people shrieking in such mortal fear below were apim, were Homo sapiens. While I fought to keep the slavers away I saw something of the victims below, and I formed an idea why they had not fought back. They all seemed to be either old men and young boys, or women and children. I heard some of them yelling as I swooped over their heads: “Jikai!”

“Hai Jikai!” they were yelling, some in feeble croaks from narrow lips. “Jikai . . .”

In this stupid affray against these devils of slavers that was the first time any idea of calling it a Jikai had crossed my mind. Was it a Jikai? To dub any feat of arms a Jikai meant it was a superb example of honor and glory and nobility, as well as a crafty use of downright cunning where necessary. You will know how I regard the use of the word Jikai, and so I decided there, as I swooped and fought, that this might be a little Jikai, a very little one . . .

And so, thus boasting to myself, I came to grief.

A stux transfixed the throat of the fluttrell. The broad and heavy head of the flung javelin jutted through, clotted with blood. The fluttrell would have been hard to manage, anyway, after his ferocious primeval instincts had been allowed full play in tchik, and so that stux was one way of settling the matter. I half fell, half leaped off, sprawling head over heels onto the dust. There was no time to lie winded. How different the scene when viewed from the ground than the view aloft!

A pack of people were already chained. Slavers were strutting past them, some flicking whips, some beating them with the flats of their thraxters. The lance-sword was much too unhandy a weapon down here.

I took the longsword into my fists again, and charged.

This time the flutsmen must have decided to get rid of me as the first priority. I had been hampering their operations and they had so far not killed me. They had tipped me out of my voller, they had brought down my wind-eater; now they would cut my legs from under me, and see how I liked that. A bird with widespread wings dived for me, skimming the ground, his legs tucked up. The flutsmen with slaves to carry back to whatever hell-hole they had oozed from would not risk crying “Tchik!” to their birds. The problems of bringing the fluttrells under control after that ferocious call had clamored bloodily in their pin-brains were too long-winded. This is just another reason why the fluttrell does not appeal overmuch to me, magnificent bird though it is. Some of the other flying animals of Kregen can do a bloody enough job of tchik and still be guided by their riders.

Now I could swat the long tongue of the lance-sword away and fling myself sideways and, leaping up, slice the longsword in a stroke that parted torso and thigh. That is a canny stroke when given to a rider on the ground; it is more difficult and thus more aesthetically satisfying when delivered to a rider flying. Then the swordsman must fling himself, all doubled up, under the flashing wingbeat and time it just right if he does not want his head staved in.

My head remained intact.

Other flutsmen attacked.

They came singly, and then in pairs, and threes.

About this time I knew that eventually one of them must finish me. It was not that I was growing tired —

for tiredness is a sin I do not admit into my consciousness — but that the odds were stacked. Amid a welter of flashing steel one blade would slip past as I dealt with another and so drink my life’s blood. The fury in me would have melted the Ice Floes of Sicce.

That I, Dray Prescot, Krozair of Zy, Lord of Strombor, should perish thus miserably!

The battle roared on. Men were yelling. Women were screaming. The flutsmen shouted strange high oaths calling on their gods and saints and devils, and rushed at me, and fell before the level, lethal sweep of my longsword.

But, for all that, a stux grazed across my chest, drawing a line of blood. That came from leaping away from three stuxes flighted together at my back. Now, had Turko the Shield stood, superb in his muscled strength, in his wonted place at my back, those stuxes would have been deflected and I would not have turned into the glancing blow from the front. The shield in the voller had gone down with the rest of my belongings. She hadn’t smashed up, but in the scant seconds I’d had before tangling with the flyer I’d seen she’d cracked up with due finality. So the battle roared on. These slavers, from whatever racial stock they came, were scrawny fellows, much addicted to beads and chains and flourishing trinkets of silver and brass. Twice I was able to let slip my hand and so, reaching out, grasp a string of beads, and jerking the fellow in, give him a knee in the groin, and thunk the hilt of the sword down onto his leather-capped head. They didn’t get up again, after that treatment.

Still and all, time was running out for me. This wouldn’t go on for very much longer. A few shouted words from a huddled group of slaves — although, truthfully, they weren’t slaves yet, nor would be until I was dead — revived me.

“Hai Jikai! Fight, Jikai, fight the evil rasts!”

Well, it seemed that even if these poor people were the old and the young, the women and the children, the sick and the lame, and could not fight in deeds, they could fight with words. What those oldsters started in catcalling the slavers would have done credit to the flintiest hearted paktun in all Kregen, and a paktun, a mercenary who has gained renown far above the mass of his fellows, knows a juicy vocabulary indeed. I braced myself again and struck and struck. About me whirled the beige-white wings of the fluttrells, feathers flurried in the power of their smiting, bringing thronging memories of other combats against other flying monsters of the skies. The scene in the dusty outskirts of the burned village, which stood at the head of a valley trending from the foothills, must have made a macabre sight. A lone man, blood splashed, his brown hair wild, the long brand in his fists stained with gore, jumping and dodging, smiting and slashing, always on the move, always striking out with ferocious blows that degutted and decapitated, this man must, I think with no little remorse, have struck terror into the hearts of the bravest of the flutsmen. But, to give them their due, they did not flinch from their assaults.

A line of tethered flyers with their rows of saddles already half full of dazed and unhappy captives waited to the side. These extremely large flying beasts were rofers, able to carry whole families through the upper levels. I maneuvered myself toward them, past chopped slavers who sought to bar my path, and soon came up to the first rofer. He was a docile enough beast and did not try to bite me as I struck down his rider and began to slash the thongs fastening the prisoners. They gaped at me.

“Run!” I bellowed at them as I freed them. “Run and hide, get to safety!”

I had to dodge a flying stux then, and the shaft thudded into the earth. An oldster with white hair — which meant he was two hundred years old at least — quavered at me as he slid from the high saddle.

“And you, Jikai? And you?”

A javelin hurtled toward the oldster. I took a step and with that old Krozair skill beat the stux away so that it caromed over and flew upward again.

“Never mind me, dom! Run!”

The fugitives could scarcely comprehend what had happened to them. They scrambled down. What with slashing at binding thongs, and beating away javelins, and striking down flutsmen foolish enough to come too close, it was a warm few minutes’ work. I bellowed at the people again, yelling at them in fury.

“By Vox! Run, you famblys! Get to safety!”

A fambly is a gentle word for a genial kind of idiot, an affectionate insult. They ran. The oldster lifted his empty hands.

“By Hanitcha the Harrower! Were I but a hundred seasons — no, fifty seasons, by Krun! — younger than I am, I would seize a weapon and join you! Hai Jikai!”

There was no time for heroics.

There was precious little time left for anything.

The very fact that these miserable slavers were bothering to capture old folk meant they were mean souled, and desperate for slave-fodder. Only slavers frantic for the foul substance of their foul trade would trouble to enslave these old folk. There were a number of young mothers there, clutching their babies to their bosoms, and these would fetch a high price on the block. Fresh blood dripped from me, and now much of that blood was mine.

I missed a stux and a wing of the wicked broad head sliced my left shoulder. I cursed. The oldsters and the youngsters and the mothers were running for the head of the valley where palines grew in luxurious and yet ordered abundance. I could see the gorgeous glow of the yellow berries and I would have given a very great deal indeed to have a mouthful to suck on, there in the heat and dust of the press. And the press was all against me, all against a lone man. I swirled the longsword and I husbanded my blows, and no longer allowed the blade to strike deeply enough to dispatch my man. I had noticed that the flutsmen’s heads had been lopped off as I struck, and I knew that to be the signal that I was consciously exerting too much strength, and thus betraying the growing weakness overtaking me. This could not go on much longer.

Then I saw the final mark of doom.

Over the ordered rows of the yellow-berried paline bushes flew a great crowd of mirvols. The brilliance of the riders’ clothing and armor gave me no hope. They swept on effortlessly, their weapons winking on the backs of the flyers, brave in the mingled streaming light of the Suns of Scorpio. They swooped down in a maelstrom of flashing wings to finish me.

I felt a blow sledge across the back of my head. I felt it very briefly. My skull is thick, but the blow felled me. And, as I pitched forward into the blackness of Notor Zan, I had the last thought that, anyway, all this had been no business of mine.

Chapter Three

“That, Notor Prescot, is your problem.”

The wonderful world of Kregen under Antares possesses, besides the twin suns, seven moons. When all of these nine luminous bodies are below the horizon there rises Notor Zan, the Tenth Lord, the Lord of Blackness.

I clawed back out of the star-spangled black cloak of Notor Zan to hear a gruff but firm and kindly voice saying: “So you still live, Jikai. Truly, your gods hold you in high favor.”

Even then I was canny enough, through the clanging resonance of all the bells of Beng-Kishi, that carillon ringing in my skull, to understand that this man was not prepared to commit himself to mentioning any specific god or spirit or guardian. He would no doubt wish me to commit myself first. My eyes opened and I blinked.

He was not a flutsman.

He was apim, like myself, a tall, well-built, grave man, with eyes that showed a deeper pain, even, than that caused by this attack on his village. For I could now guess what had happened. The maelstrom of mirvols which had swept about me had borne, not reinforcements for the flutsmen, but the returning warriors of the village. And so it proved. I had been dragged out from the corpses, washed, placed in a bed in the chief house, watched over, my head bandaged and my various cuts doctored, and now, here came a fusty little doctor bearing his linen-covered tray of needles. My host said in his grave way: “Allow Hernli to see to you, Jikai, and then, when you are recovered, it will be my privilege to talk to you.”

I did not reply. The doctor was already sticking his acupuncture needles in me, and twirling them, and with that amazing fluency that never ceases to astonish, he banished my aches and pains. I do not smile easily, but I cracked a grimace for the doctor, at which he started back, and said, “Are you still in pain, Horter? That is strange, for I have found the lines with exactitude—”

“No, Doctor,” I croaked out. “You did fine.”

Then I went to sleep.

When I woke up I lay for a considerable time, content just to lie there and take stock of my surroundings. A makeshift frame roof had been flung over the burned shell of the house. From the few items of furnishings I guessed the houses had been luxurious — truly luxurious — within their mud walls. You can never judge the interior of a house from the exterior, although an approximation can obviously be reached, and I judged these people to be well off, comfortable, living with a high degree of sophistication, basing it on their ancestral riches of vast herds of cattle, the enormous profusion of paline bushes, and — and what? With cattle and with palines a village is rich indeed, and by good business dealings may acquire whatever they need. Certainly, I had seen to it in my redevelopment of Valka after we had banished the aragorn, and in the work in Djanduin after the disastrous civil wars, that building up the cattle herds and planting palines had figured very high up on the list of priorities. And, anyway, these people would keep other animals and grow other crops as well. No, they weren’t poor. When a young girl, rosy with shyness, came for me and I shambled out into the shafting rays of the twin suns and looked about on my way to take the baths of nine — for the complex of the bathhouses down by the stream had not been burned — I saw more of this place.

I will say at once that I liked the spread. In the days that followed as I built back my strength I explored Paline Valley — for that was the name of the estates — in the company of a man for whom I developed a growing friendship and affection. This was Nulty, a loyal body-servant to the lord here. He was a great shambling fellow, with a shock of hair, bulbous nose, and a pair of sharp eyes, and he came up to the middle of my chest. He was originally a gul — that is, a craftsman and no slave — until he had taken service with the lord here.

We were in Hamal, which is a mighty empire on the southern continent of Havilfar, and these people were all Hamalian — people for whom I had formed an ambivalent attitude. They professed the state religion of Havil the Green. Still, at this time, Green was anathema to me, although I was, I think truly, learning. There were other religions: the finer and purer religion of Opaz —

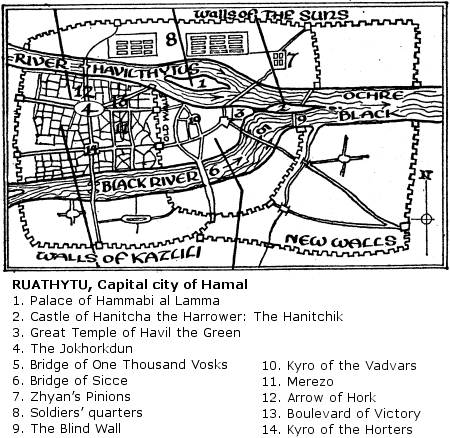

the great Twinned Invisible Spirit, so predominant in other and nicer parts of Kregen — had a small following in Hamal, generally in secret; and, too, the evil cult of Lem the Silver Leem was edging in with lures of cheap passion, quick wealth and dark arts, ousting devotion to Havil the Green. Like it or not, religion has a potent power in the material world as well as the world of the spirit. So I knew I must tread carefully in my dealings with these folk, as I had earlier when I had spent a fruitless sojourn trying to find out what made a voller tick. My own flier was a total wreck. The gear had been taken out and stacked in a room that had been given over for my use. This meant, of course, that they knew I was not Hamalian. Delia had stowed away much besides food and good clothes — weapons strange in Havilfar. The Lohvian longbow, for one. The longsword for another. Also she had packed four rapiers and four left-hand daggers. Much of my personal gear — the razor, the toiletries, the shoes, the wide Vallian hats — proclaimed me a foreigner. So: “And, Notor Prescot, are you to visit our capital city of Ruathytu on your travels? I wish you would remain here with us in Paline Valley for a time.”

I was sitting munching on palines, which are superb, and I looked up as the lord entered. I did not stand up. I must have been half mad at the time, what with this and that and the fight, and I must have blurted out my name when they asked me. I have had many names, and so far have told you of only a few of them. Now the lord, whose name was Naghan, sat beside me and took up a handful of palines.

“You are very kind, Notor Naghan. Paline Valley is charming. The coolness of the valley after the veld, the greenness of the trees — and the palines! — all tempt me. But, as I said, I am a traveler.”

“Come, Notor Prescot! You are the Lord of Strombor. We have dealings, here in Hamal, with your great enclave city of Zenicce, far away on the continent of Segesthes. Here we are isolated from the main currents of political life in Hamal. We tend our flocks and grow our crops, and we grow rich, and essentially we must protect ourselves.” He paused then, his grave face growing longer and more savage. He was thinking that protecting himself came high. He and his fighting-men had been away, flying their mirvols to check a predatory band of the wild men from over the mountains, outside the sway of the Empire of Hamal, when the slavers had struck. The slavers must have been preparing to attack the village and then no doubt had been of two minds when the fighting strength had flown off. To take up the poor residue would not bring much in the way of sales figures, but the catch would be cheaply won. We all knew the decision to which they had come.

This Naghan was a Notor, a lord, and his rank was that of Amak. An Amak is one rank below an Elten, and an Elten is two ranks below a Strom. Although he was of the minor nobility, he was unquestionably a noble. He had discovered I was Dray Prescot, the Lord of Strombor, and that placed me at once far higher in this scale of nobilities. I felt obscurely embarrassed about this. As I have said, a lord of one of the enclaves in the city of Zenicce ranks as a king, and is often given the courtesy title of prince. Lords of Zenicce tended to regard other ranks as baubles — and I had more than once affronted my friends by hinting that to a clansman a lord of Zenicce was a poor thing. But, I must be honest, I feel always for my clansmen, for Strombor, for my island of Valka, and for my country of Djanduin a special kind of affection.

I, Dray Prescot, am also a Krozair of Zy.

And if I think back on what I have just said, and realize how many times I say “my” this and “my” that, you will take me for an egomaniac. So it was that I was polite to Amak Naghan, and talked with him, and learned of his estates here in Paline Valley, and of his problems. Of all these problems, chief above all, was the problem of his son Hamun. The lad was effeminate. Well, here on Earth that is no great matter. It is something a father can learn to understand. But on Kregen, that world of which I then knew so little and even today know barely much more, there are very few places where an effeminate lad, son to a noble, can hope to survive. Here right on the border of Hamal, with the Mountains of the West hard up southerly of the estates, was no place for a lad who could not wield a sword and stride a mirvol and fly to face the enemies who would take from him his birthright. There are many customs and laws on Kregen regarding inheritance. It is not necessarily lawful for a son to succeed his father in all his titles and estates; they have to be fought for. By these means new men and women are continually pushing up from below, but the laws of inheritance check what might become a situation of complete anarchy. If a man simply cut down Amak Naghan he would not automatically become Amak in his turn. Kregen is far more subtle in her ways than that. So Hamun ran a serious risk.

“In the capital, Ruathytu,” I had said, once, “wouldn’t he find people like himself? It is a civilized, policed, orderly city. The laws of Hamal—”

“The laws! Aye, the laws are strict in Hamal, Notor Prescot. Exceedingly strict. But I would not send Hamun there.”

I knew — better than Naghan — the strictness of the laws of Hamal. He had not labored in the Heavenly Mines with a number branded on him. I had. I knew about the Hamalians and their lawful ways.

“But, Notor Naghan,” I said, controlling a surge of desire to clear out at once, “Ruathytu is renowned for its graces, its architecture, its baths, its aqueducts, its sports, all things to make life for a lad like Hamun—”

“Do you think, Notor Prescot, I would allow my acquaintances in the city to know I fathered a son like Hamun?” His face was graven now in lines of pride and fury and shame. “I have the honor of my family close to my heart. We have the honor of being a ham family — we place the ham before our family name. No, Notor Prescot! I, Naghan ham Farthytu, Amak of Paline Valley, will not be shamed before the empire by my son!”

There was nothing to say to such granite conviction, such iron will. He was demanding from his son that which the boy could not give him. It was rotting away the life of Amak Naghan. At last came the day when I firmly resolved to leave. Delia had placed plenty of money in the flier. She had had the forethought to make most of it up from Havilfarese currency, fat golden deldys, shining silver sinvers, and a lesten-hide bag of bronze obs. To make the appearance of a traveler more effective she had thrown in a few coins of Pandahem and Murn-Chem and Balintol. Coins, gold especially, find their way all over Kregen from the mints of their making, and merchants have little scales set up to check weights; a cunning merchant can tell the value of a gold coin and its percentage of impurities and alloys to perfection. Of course, the word for carats in Kregish is not carats. So it was that there was money for me to buy a mirvol.

Naghan ham Farthytu drew himself up with a grave and haughty look. Like many people out here in the frontier sections he often wore a long white robe, comfortably slit for arms, girded with a golden tasseled cord. His jeweled curved dagger depended from gold chains. His scarlet slippers were studded with gems, embroidered with gold lace. Around his neck a chain of beads blazed with the richness of gold and the scarlet of scarron — that incredibly beautiful gemstone of so fine and fierce a scarlet that is prized above diamonds.

“I do not wish to believe, Notor Prescot, that you insult me with intention.”

I took his point.

The upshot was that because I had fought for Paline Valley they conceived themselves in my debt. Besides giving me a mirvol, the finest flying specimen they had, they heaped gifts upon me that further embarrassed me.

I stood by the mirvol. He was a fine flying wonder, and no mistake. Beside him the pile of my belongings stretched lengthways and broadways and high. As I stood there, Hamun ham Farthytu, with his mincing walk, came up with a small carved set of miniature pieces for Jikaida, the board game that is so much a way of life in many parts of Kregen.

“My village owes you a great deal, Notor Prescot.”

I stared at the pile.

“And how, good Hamun, am I to load all this mishmash onto the back of this single mirvol, and find a space myself?”

Hamun was not like his father. Had I been speaking to Naghan I would never have said that, for I knew Naghan’s reply, as mine would have been in like circumstances, would be a quick: “You shall have as many flying steeds as you require to carry you and your belongings safely.”

“That, Notor Prescot, is your problem,” Hamun said.

In all probability he would have made a good monk, or a stylor, or an actor — although you have to be tough to be an actor in some of the more ferocious Kregan plays — but he was an Amak’s son and therefore he was destined to fight his way to his own nobility.

Now I discarded everything that was not essential. On Kregen that meant everything except weapons and a little food and money.

“Remberee, Notor Prescot!” they called after me as I mounted into the air. “Remberee!”

“Remberee, Paline Valley!” I shouted back.

The wide wings of my mirvol carried me high into the air bound for Ruathytu, capital of Hamal, shining and resplendent under the Suns of Scorpio.

Chapter Four

Hamun ham Farthytu, Amak of Paline Valley

Strange are the ways of the Star Lords, as I have many times found out to my cost. Strange, too, are the ways of the Savanti nal Aphrasöe, those mortal but superhuman men and women of the Swinging City, where I had bathed in the sacred Pool of Baptism of the River Zelph and so secured a thousand years of life and bounding good health. But, strange, too, are the ways of pure ordinary fate. Simple, disinterested fate for once took a hand in creating conditions that afterward would profoundly affect my life on Kregen.

Chance alone made me realize as I winged through the level air that the hilts of four rapiers were revealed as the slipstream threw back the flap of cloth in which they were wrapped. Delia had placed in the voller four rapiers and four main-gauches. I had promised to give Nulty a rapier and left-hand dagger. He had expressed interest in them, saying that rapier-and-dagger fighting was all the rage among the bloods in Ruathytu, so he had heard, and he had a mind to see what all the fashionable fuss was about. So — how could it be I carried four sets?

Nulty deserved to have my promise to him honored.

With a half-reluctant pull on the guiding reins I wheeled the mirvol in the sky and winged back toward Paline Valley.

If you have listened to these tapes of my life on Kregen you will already have guessed what chance had let me in for. Kregen is a world that demands the utmost from a man or a woman. Half measures will bring only catastrophe. I knew that when the slavers had attacked, a messenger had somehow scrambled off astride a volclepper, one of those small and exceedingly fast flying animals of Havilfar, and had succeeded in reaching Amak Naghan ham Farthytu as he was marshaling his warriors. Their return had saved their village and saved my life.

But the wild men from over the mountain had not thrown away the chance thus vouchsafed them. They had visited Paline Valley.

They had destroyed, they had wasted, they had not cared to take prisoners for slaves; preferring to slay, they had obliterated that smiling valley. I came in on the tail end of the fight and was able to speed the wild men on their way with biting shafts. A slight struggle followed as I mopped up a party assaulting the Amak’s house which, burned and crumbling, still held men and women who resisted. In a wild skirling of blades, I went through the wild men, smelling their stink, seeing their knotted braids of black and greasy hair, sundering their shields, lopping heads, degutting. It was all a dreadful reprise. But, this time, there was a still more dreadful difference.

When the last of the wild men made his decision to stay and be killed or take flight and save his skin, I turned to the barricaded door and bellowed in a cracking voice: “They are gone! Open up! It’s me, Dray Prescot.”

The door did not open.

I heard a thin and scratchy voice — Amak Naghan’s voice.

“We are all — sore wounded — Notor. Near to death. We — cannot — open the door.”

The last of the wild men had gone and I felt they wouldn’t stop running until they were safe beyond the mountains. I looked around. A fallen beam made a handy battering ram.

“Stand clear of the door!”

“We — cannot stand—”

Smash went the beam at the door. The sturdy oak creaked. Lenk wood, it was, bound and barred with iron. Smash went the beam. These people had been good to me and I felt a cherishing affection for them. Now they were all slain. The door went in with a splintering ripping and I plunged through. They must have crawled here after fighting hard and long and, covered in wounds, barred the door and sunk down to rally for the final attack. Nulty lay to one side, unconscious, breathing like a blown stallion, his body a shiny mass of blood. Other men and women were there, all wounded. In a corner lay a pile of bodies. To one side lay the corpse of Hamun ham Farthytu, the Amak’s son. I bent to Naghan.

“It is finished, Dray Prescot. All done.”

“No, Naghan.” There was a pitcher of water, and I moistened his lips. He tried to drink, but only choked and coughed. His wounds were dreadful. “No, Naghan, my friend. You will recover. Paline Valley will bloom again.”

“We saw you fighting — through the chink in the door — we saw you. You are a great Jikai, Notor Prescot. But it is all finished. The honor of the family of ham Farthytu no longer matters.”

“Oh yes it does!” I said to him sharply. I thought he was dying, and no man should die without some hope. “You leave a great name, a name of which to be proud.”

My Anglo-Saxon forebears would have understood that, to die well and leave a good name. His head rolled restlessly from side to side. I do not think he was in pain; that had numbed in these final moments.

“Our name will be forgotten, Dray! Obliterated! For my son is dead.”

There can be few words in any human tongue more dreadful than those: My son is dead. Before I could answer, Naghan went on: “He did not die well. He ran and hid. The wild men found him. They mocked him. They — they had sport — with him. I died, then, I think, before I bit the sword.”

“Rest easy, Naghan—”

“I shall never rest, Dray, in this world or on the Ice Floes of Sicce.”

So, there, in that shambles, chance played a card that put the idea into my head. It existed, of itself, full-grown like Athena in less than a heartbeat.

Naghan ham Farthytu was dying. His thoughts clouded. His stern grave face slackened, and spittle and blood ran from the corner of his mouth. He started to choke and I eased him. He was no longer truly of the world of Kregen.

I said: “Naghan ham Farthytu, Amak of Paline Valley.” I spoke with formality and he responded to my tone. “If you will it so, your name will not be forgotten. It will be regarded with the honor and respect it is due.”

He was dying. But he was past my foolish notion of going to Ruathytu and there erecting a monument to him and his family, a noble marble cenotaph in the Palace of Names. His bloodied hand lifted and grasped my sleeve. I bent closer. He rasped out the words, now, spitting blood, struggling to force his dying body to obey the commands of a brain abruptly clear and utterly determined. So, I truly think, chance brought me to that spot, and to the last words of a dying noble, and chance made me anticipate what he would say, what he would ask, even as I discarded the notion of erecting that monument in the Palace of Names as the only thing I might do for this man.

“Dray Prescot! You are a man of honor, a Jikai. It is my dying wish you take upon yourself the name of ham Farthytu! I would think well if the empire saw in you and your prowess the name of ham Farthytu.”

I hesitated. Stealing names can be habit-forming.

But Naghan gripped my arm, and his lined face implored me. He whispered weakly now, obsessed with his idea and his wishes, quite unable to see past his own desires to the problems attendant on the other side of the question. This was a thing he would never have asked of me in life. In death he had a privilege.

“You will do this for me, a dying man, Dray Prescot?”

Still I hesitated.

Then: “Yes, Naghan. I will.”

His sigh started deeply and finished in a choked fit of bloody coughing. But he would not let me go. His grip tightened feverishly. We must have made a macabre pair, blood everywhere, dead men and women scattered about, and, at his feet, the dead and dishonored body of his son.

“Dray — Dray — promise me, promise me by your god, you will take the name of ham Farthytu—”

How cheap to have betrayed him! To have promised by Havil the Green! He would have believed —

and I would be just as foresworn when I broke the oath.

“By Opaz, Naghan, I will use the name in Hamal. I will go to Ruathytu and there I shall be Naghan ham Farthytu.”

“No! No!” He tried to shake me, and his hand merely fluttered. “No, Dray! My son! My son!”

And then I saw what he truly wished.

I thought of my own father, and of the scorpion that killed him. I marveled. And then I thought of my little Drak — and I understood.

“Very well, Naghan. I will take the name in Hamal of Hamun ham Farthytu.”

“Yes, yes, Dray.” He was going. “You will be Amak. Amak Hamun. I wish — wish it so . . .”

I stayed with him until he died.

When he gave the last death rattle, a sound I have heard many and many a time, I stretched, for I had held him at the last to ease him, and Nulty from behind my shoulder said: “He was a good man, Notor Hamun.”

I looked at Nulty.

His broad-barreled body with its glossy covering of blood made a ghastly sight.

“I thought you were dying, Nulty.”

“No, Notor Hamun. This blood is from the wild men, may Hanitcha harrow them to hell! I had a crack on the head, I think.”

“You called me Notor Hamun.”

“I heard what the Amak said.” Then, because Nulty was no slave but a free servitor, he could add: “I wish you well, Amak. Havil the Green could not have chosen better.”

If he could read my mind on what I thought of Havil the Green he’d change his tune!

So . . . while I spent my spying expedition in Hamal I was to be Hamun ham Farthytu, Amak of Paline Valley.

The incentive to carry on my work had received an enormous boost. Over the matter of names I have always been choosy. A name is a precious commodity; abstract, it yet holds a potent sway, and in many minds of Kregen, no less than minds of Earth, is regarded as a solid and material object, a thing to be grasped and, once grasped, to give power. To those who wish for success, the remembrance and the efficient handling of names are essential.

We went outside and, in truth, Paline Valley was a sorry place. Nulty and I spent only the briefest of spells in cleaning ourselves, not sparing the time to take the baths of nine, then we set to the mournful burying. When all was done we rested and ate and drank, and, then, just sat. Nulty, a blocky man of great strength both of body and of mind, had the pragmatic Kregen way of regarding disaster and death. He was not in shock. At least, I did not think he was. He surprised me, at first, when he spoke his mind; but on reflection what he said made the soundest common sense.

“Now you are Amak Hamun, and I am the only survivor here, and it is fitting I should tender you my allegiance. I had been charged with the old Amak’s son . . . to no avail.” He hesitated.

“You do not have to excuse him to me, Nulty.”

“It is not that, Notor. The old Amak is dead. Amak Naghan is dead. But there is now a new Amak, Hamun, Naghan’s son.”

“That is not true,” I said. I sighed. “But that is the way Naghan wished it to be.”

Nulty fingered his thraxter, that straight sword of Havilfarese fighting-men, where he had cleaned it with spittle and brick dust. His words were meaningful.

“Amak Naghan desired that his son should bring honor to his name. I follow his son, now, and I pledge my sword to the same high purpose. Amak Hamun, Naghan’s son, will bring honor.”

I took his point. I was in no frame of mind to argue with him. So I said: “Very well, Nulty. You may come with me to Ruathytu.”

“Yes, master,” was all he said. It was sufficient.

Chapter Five

Birth of a yokel at the shrine of Beng Salter

In the full determination to discover the secrets of the fliers of Hamal I made no urgent rush to the capital city. Nulty and I took our time. We had three mirvols between us, one the magnificent animal presented to me by Amak Naghan, the other two lesser beasts rounded up by Nulty after the raid, all that were left of the remudas perching on the mirvol towers up by the highest slopes of Paline Valley. There was no rush because it was necessary for me to learn as much as I could of the country. We swung slowly southward and eastward, for the capital, Ruathytu, is situated at the junction of the River Mak, the Black River, with the larger River Havilthytus, some sixty dwaburs inland from the eastern coastline. We had, according to Nulty, about two hundred and sixty dwaburs to go to the city in a direct line — as the fluttrell wings, in Hamalese vernacular. This 1,300 miles or so we greatly lengthened by making detours and visiting many of the towns and cities en route, and of generally, in Nulty’s case, getting over the shock of seeing his home so brutally destroyed. He had had no wife or children, desiring none; all he had cared for had been the old Amak and, as I knew, his son, Hamun. So we wandered along our way, and we had a few fine adventures, too, which I will not mention now but many of which would undoubtedly form vastly exciting stories in their own right.

Again I was reminded how strange are the ways of chance.

Because it was the fashion out on the frontier territories to wear a white robe, cinctured in with a tasseled cord, I had tried the fashion and found it convenient. The hem of the robe came down to just above my knees. Nulty, whose own robe was more in the nature of a smock, insisted I wear the gold-and-scarron chain of beads we had with reverence taken from Naghan. The scarrons blazed a true and brilliant scarlet. Because I have a fondness for the old brave color, as you know, I was persuaded to wear them, and the curved gold-and-jeweled dagger, and the gold-and-scarlet slippers. To Nulty this attire was proper for an Amak.

To me, it was light and comfortable, for, remember, on much the same latitudes far to the west lie the great deserts of Loh. Loh as a continent of mystery possessed great fascination for me. One day, Zair willing, I would go there and discover if all that men whispered about those secret walled gardens, and those girls with the veils, and all the other mysteries of Loh were really true. Nulty didn’t care much for Lohvians. And he did not care much for the Pandaheem, either, the people of that large island off the northeast coast of Loh, and just over the equator northwest of Havilfar. The chance of my attire came one day when, along with a party of pilgrims, we flew out to visit a shrine reputed to possess quite remarkable healing properties, through the magical powers of the bones of a Beng buried there. A Beng is, to give a near approximation, a Kregan saint. Nulty wanted to know if this notoriously powerful Beng Salter’s bones would cure a pain in his left hand, where the fingers, from time to time, abruptly cramped and the palm of his hand contracted, so that he had to bash it against a wall to flatten it out.

We landed by the simple marble shrine before the cleft in the rock, where a waterfall tinkled. Water is precious in these latitudes of Hamal. The grove was a pleasant and sweet-smelling place, and the aura of peace came fresh and comforting, so that no one objected when the guardians insisted we remove all weapons before entering.

Normally, of course, no one would voluntarily relinquish his sword on Kregen. But here, with the benign, smooth-faced guardians in their long robes, and the holy softness and tranquility of the scene, no one objected. There were about a dozen of us as we went into the shrine, carefully observing the fantamyrrh as we did so. Inside the place was cool with shadow, somnolent, tranquil, and I felt that faith would have a chance, here, to work its wonders.

The ritual was gone through by those who had come here with intent. We as mere onlookers watched. I hoped Nulty would find his cure.

The feeling of peace came to me, I remember with perfect clarity, with a benediction. This, in truth, was as life should be lived. Life was not always a mad business of rushing and pushing about, of flashing swords and flying bolts, with blood and death as permanent companions. I felt this pleasant relaxed emotion so strongly that I was perfectly well aware I was weaponless, and I did not mind. As we watched, those who had earnestly besought the dead saint to cure them rose and shuffled back, and already one or two were disappointed, one or two beginning to rub feeling back into a hand or limb they had thought paralyzed.

Nulty was working the fingers of his left hand, but he had not suffered an attack for some time, and so there was no real way of checking the efficacy of the Beng’s bones.

A man — he was apim — dressed very beautifully in dandy clothes jostled me as I turned for the exit. This fellow wore a blue shirt whose front foamed in a veritable avalanche of lace. His waist was nipped in by a massively wound cummerbund of bright green, and his gray trousers were strapped beneath his shoes. Over his right shoulder ran a brilliantly embroidered baldric. The scabbard was empty. These things I noticed about him, as well as the interesting fact that his face was far too apoplectic a red for his own good, his blue eyes protruded in an altogether repugnant way, his dark hair was cut too short for good taste, and his whole demeanor suggested a man of viciously quick temper. He gave me no time either to curse him out of my way or to apologize. I scarcely think I would have done the latter, and the former accorded ill with my euphoric, benign state of mind.

“Onker!” he bellowed. “Get out of my way, you rast!”

And, incontinently, his right hand whipped across his body and groped for the hilt of the sword that was not there.

I did not move.

“Cramph!” he said. He was panting, and into those protuberant blue eyes flushed a betraying bloodshot glare. “Stupid clumsy yetch!” And then he realized he was not grasping the hilt of his thraxter. Other people stopped to look. The fellow saw I had not moved. He brayed his contempt. “Ninny! Nulsh! You are a nothing! I can see from your clothes that you are no fighting-man! A warrior takes up arms—”

Soft-spoken guardians appeared, their robes rustling. I let them hustle me away, for I did not wish to kill the fool in these hallowed precincts.

When we were outside I retrieved my weapons.

Nulty came up, rubbing his hand, frowning.

“Tell me, Nulty; who was that cramph who insulted me?”

“I do not know, master. But he has departed. He and his retinue left in a fast voller.” And Nulty snickered, flexing his fingers. “You’ll never catch him on the back of a mirvol.”

Something of the tranquility of that place clung to me still, for I answered, and I admit with astonishment even as I spoke: “Let him go, Nulty. If he crosses my path again I’ll settle accounts then. Now I need a good long drink, and a full plate of cold vosk and a few loloo’s eggs — with a salad.”

Later we discovered the man’s name was Strom Hormish, from a town called Rivensmot in a small kingdom of the Empire of Hamal. I brushed the pesky idiot from my mind. I had cold vosk and loloo’s eggs to deal with, and although I did not care to spend the required amount to buy a flagon of wine of Jholaix, we drank a rather good local vintage that commended itself to us against parched throats. Nulty was beginning to get the hang of some of my idiosyncrasies.

“That idiot Strom Hormish took you for a spineless weakling, master. You did not immediately reach for your sword, as a fighting-man would do instinctively.”

“Am I not then a fighting-man, good Nulty?”

He made a comical face. “That is not what I mean, Notor.”

“I know. But — what did he mean about these clothes?”

Here Nulty’s face registered further aggravation.

“I am told that the — would you call them sophisticated? — people of the cities laugh at our clothes.”

He went on to wax enthusiastic over the white gown, cut to tunic length, as I wore it. He mentioned the different styles, and the embroideries, and all these names had meaning, but I will not weary you with them now. “So, because of your clothes, he thought you—”

“A yokel!” I brayed out, enraged.

“Aye, master.”

And then — I swear it as Zair is my witness! — once again chance threw an idea into my blockheaded skull. Through two chances I had a scheme. I wore clothes that dubbed me a yokel, a simpleton from the sticks. And I had not betrayed the hallmark of the warrior.

From these two things I could construct a device that should serve me in good stead in Ruathytu, and, into the bargain, afford me some considerable amusement.

Truth to tell, I needed a good laugh about then.

As you know, I, Dray Prescot, do not laugh easily. But I had been living in Valka with Delia, and we had the twins to occupy us, and what with this and what with that, I had been laughing so that the laugh lines had managed to find a lodgment in my grim, ugly old face. Seg and Inch had been there too after we had returned from Migladrin. For the various reasons of state, of politics, of economy, they had had to return to their Kovnates, and so, as was my wish, I had come to Hamal alone.[2]

So I nodded and said very seriously to Nulty: “Very well. I shall wear the clothes of a yokel and a simpleton. And I shall watch my sword hand with great attention. And you, good Nulty, brag no more of our fighting prowess, and give no one any idea that Hamun ham Farthytu is familiar with a sword.”

“Yes, master, as you command,” said Nulty. But I could see he was much put out by having the cool and comfortable clothes of his home regarded so contemptuously. A yokel. Well, so be it. I could play the part, and I fancied I could carry off the simpleton part of it with far too uneasy an ease . . . We flew on apace toward Ruathytu, the capital, and I own to the traveler’s curiosity to see places of which he had heard much. I will not weary you with all the strange creatures and peoples and customs I encountered en route; suffice it to say that whenever it is essential for you to know, then I will talk of these things. There came a day when, with Stormclouds darkening the sky and the first heavy spatters of rain smoking into the dust, we alighted at an inn in some half-forgotten little town in the center of Hamal. We were within the boundaries of the Kovnate of Waarom, for, as I have mentioned, the Empire of Hamal is made up of a number of kingdoms and Kovnates owing allegiance to the Emperor of Hamal. Waarom was a dusty, idle, listless place, populated by peoples of a number of different racial stocks, and I believe the chief industry was ponsho farming, with a little surface mining here and there. Nulty and I needed fresh leather bottles of wine and provisions of various kinds, and so we were not too particular. Outside the inn on perching towers the various flyers huddled up against the rain with flurried feathers, their backs turned to the wind, shaking membranous wings.

“Look at them, master!” said Nulty, giving his mirvol a slap to send him scuttling up onto a vacant perch.

“This is a miserable dump, and no place for an Amak.”

“Miserable or not, Nulty, it is a roof over our heads.” I sent my first-class mirvol up onto his perch on the tower. “Although I could wish for a covering for our mounts. A poor place, indeed, this” — and I turned to look at the sign swinging over the amphora placed at the door — “this Crippled Chavonth.”

When we approached the entrance I ducked my head, for the doorway was made deliberately low with a massive oak beam, and went inside followed by Nulty.

The floor was sanded, the tables and settles of cheap purtle wood, the pine already splitting, the goblets of inferior pot-clay and crude as to shape. The wine was just drinkable; the ponsho chops, though, were tender enough, cooked by a smudge-cheeked girl in a flour-and-blood-stained apron. Nulty and I ate and drank in a companionable silence, while the other travelers in the room, apim, like ourselves, with only a few diffs to enliven the scene, talked in low voices. More than once I saw a pair of eyes lift to stare at the low ceiling.

This inn was strictly a place to take a meal, to buy provisions, and to leave. The Crippled Chavonth. Kregans have a delight in names. The local ponsho farmers, we learned, caring for their flocks, produced an animal with surprisingly high-quality fleece, and the chavonth, that powerful six-legged hunting cat with fur of blue, gray, and black arranged in a hexagonal pattern, has a partiality to fat ponshos. The local infestation of these predators had come about through an airboat crash. The voller had been bringing in prize specimens of chavonths for the Arena in Ruathytu, and after their liberation they had bred and increased and had come finally to terrorize the countryside here in this dusty little town of Urigal in the half-forgotten Kovnate of Waarom.

The ponsho farmers in this duchy of Waarom must have given uncomfortable little grimaces when they looked up at the sign of The Crippled Chavonth, no doubt wishing it to be so in fact. Peoples and animals are spread bewilderingly over the surface of Kregen, it often seems scattered at random, with only the haziest controlling influence of local evolution to be discerned. Much of this scattering of races and species, I believe, is due directly to the influence of the Star Lords; but quite a bit results from accidents like the one that brought hunting chavonths here to Waarom. The light coming through the low windows darkened and turned a deep umber. For a time, as the storm thrashed past overhead and the rain lashed down, the light vanished, and the pot-man brought out a few earthenware lamps. We finished our meal and then bought provisions to carry us through for the remainder of our journey. The storm grumbled and banged, but slowly the light came back and the lamps were extinguished. This was not one of the seasonal monsoon areas of Kregen; this rain was welcome in so dusty a Kovnate. The lingering after-rain smell carried overtones of quenched thirsty earth and green growths.

The landlord was not immediately available for us to pay the reckoning. Heavy thumps sounded from the room overhead, and then doors banged, and footsteps clumped down an outside stairway, and loud voices lifted outside. There was a confusion of shouting, laughter, and that particular kind of freewheeling, innocuous oaths that some men adopt in the presence of ladies.

“Fetch the mirvols, Nulty.”

“Yes, Notor.”

Nulty went outside — he did not have to duck his head — and I strolled after, expecting to find the landlord dealing with his important guests, who had been decently housed in the private upstairs room and served personally.

The twin suns streamed down welcome rays, and the air sparkled with brilliance. The pot-man dodged after me. He did not dare to touch my elbow to halt me.

“I will take the reckoning, Notor.”

This suited me, and I paid him, using a few sinvers from the vosk-skin bag at my waist, for I had not as yet adopted the Hamalese custom of wearing an arm-purse.

“Thank you, Notor, may Havil the Green smile upon you, Notor, Remberee,” the pot-man rattled off in a monotone.

I stepped outside the paved area before the door. Over at the perching tower flyers were being brought down and there was a flourishing of cleaning cloths as their feathers and hides and scales — for the different species — were dried after the rain and polished and made presentable for the great lady and her retinue who waited with growing impatience.

I looked at the arrogant, brilliant group of people.

They were apims.

The men were hard featured, fair of hair, thick of jaw, clad in flying leathers adorned with much jewelry and gold lace. Their weapons were those of Havilfar. The girl who was the center of this brilliant group appeared to me, grown somewhat cynical in the ways of the mundane world, I fear, as completely out of place in that company. Her bright fair hair gleamed in the lights of Antares. Her small face, pert, with rosebud mouth, pale blue eyes, and a creamy-white complexion, seemed to me that of a child let loose in a world she did not comprehend. She was beautiful, in a china doll way, someone you might admire from a distance but scarcely wish to touch.