PRAETORIAN

Copyright (c) 2011 Simon Scarrow

The right of Simon Scarrow to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2011

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978 0 7553 5721 5

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Table of Contents

Rome In The Age Of Emperor Claudius

About the Author

Simon Scarrow worked as a lecturer before becoming a full-time writer. PRAETORIAN is his eleventh novel about Macro and Cato, heroes of the Roman army; all the earlier Roman novels, including the No. 1 bestsellers CENTURION and THE GLADIATOR, are available from Headline.

Simon Scarrow is also the author of a quartet of novels about the lives of the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon Bonaparte. YOUNG BLOODS, THE GENERALS, FIRE AND SWORD and THE FIELDS OF DEATH have been published to warm acclaim.

To find out more about Simon Scarrow and his novels, visit www.scarrow.co.uk.

The Roman Series

Under The Eagle

The Eagle’s Nest

When The Eagle Hunts

The Eagle And The Wolves

The Eagle’s Prey

The Eagle’s Prophecy

The Eagle In The Sand

Centurion

The Gladiator

The Legion

Praetorian

The Wellington and Napoleon Quartet

Young Bloods

The Generals

Fire And Sword

The Fields Of Death

As ever, my first debt of gratitude is to my wife Carolyn who carefully checked through each completed chapter as the novel was written, and who puts up with me when I get totally absorbed in the tale.

CHARACTERS

Tribune Balbus - in charge of the bullion convoy

Centurion Gaius Sinius - an ambitious back-stabber

Tribune Burrus - commander of the Third Cohort of Praetorians

Centurion Lurco - practically part-time commander of the Sixth Century of the Third Cohort

Optio Tigellinus - Lurco’s frustrated subordinate

Guardsman Fuscius - a recent recruit who thinks he’s a veteran

Prefect Geta - commander of the Praetorian Guard

At the Imperial Palace

Emperor Claudius - a fair ruler, though not always a coherent one

Empress Agrippina - his wife and niece, and mother of

Prince Nero - a pleasant boy with artistic ambitions

Prince Britannicus - the son of Claudius, clever but cold

Narcissus - imperial secretary and close adviser to Claudius

Pallas - another close adviser to the Emperor and Empress

Septimus - an agent of Narcissus

In Rome

Cestius - a vicious and ruthless leader of a crime gang

Vitellius - playboy son of a senator, and long-standing enemy of Macro and Cato

Julia Sempronia - the lovely daughter of Senator Sempronius

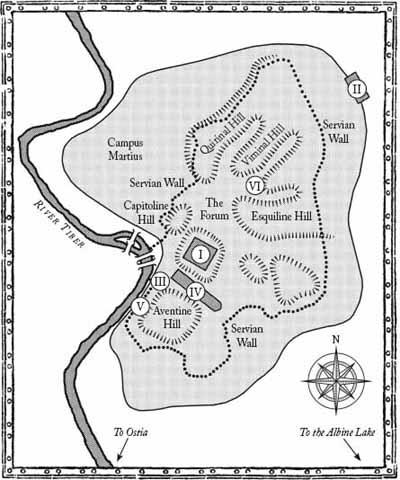

ROME IN THE AGE OF

EMPEROR CLAUDIUS

The Imperial Palace Complex

The Praetorian Camp

The Boarium

The Great Circus

The Warehouse District

The Subura Slum District

CHAPTER ONE

The small convoy of covered wagons had been on the road for ten days when it crossed the frontier into the province of Cisalpine Gaul. The first snows had already fallen in the mountains to the north that towered above the route, their peaks gleaming brilliantly against the blue sky. The early winter had been kind to the men marching with the convoy and though the air was cold and crisp, there had been no rain since they had left the imperial mint in Narbonesis. A bitter frost had left the ground hard and easy going for the wheels of the heavily laden wagons.

The Praetorian tribune in command of the convoy was riding a short distance ahead and as the route crested a hill he turned his horse aside and reined in. Ahead the road stretched out in a long straight line, rippling over the landscape. The tribune had a clear view of the town of Picenum a few miles away where he was due to meet the mounted escort sent from the Praetorian Guard in Rome - the elite body of soldiers tasked with protecting Emperor Claudius and his family. The century of auxiliary troops that had escorted the four wagons on the road from Narbonensis would then march back to their barracks at the mint, leaving the Praetorians, under the command of the tribune, to protect the small convoy for the rest of the journey to the capital.

Tribune Balbus turned in his saddle to survey the convoy marching up the slope behind him. The auxiliaries were Germans, recruited from the tribe of the Cherusci, large, fierce-looking warriors with unkempt beards thrusting out between the cheek-guards of their helmets. Balbus had ordered them to keep their helmets on as they passed through the hills, as a precaution against any ambushes from the bands of brigands that preyed on unwary travellers. There was little chance that the brigands would risk an attack on the convoy, Balbus knew well enough. The real reason for his order was to cover up as much of the auxiliaries’ barbaric hair as possible to avoid alarming any civilians they passed. Much as he appreciated that the German auxiliaries could be trusted with guarding the mint, owing their loyalty directly to the Emperor, Balbus felt a very Roman contempt for these men recruited from the wild tribes beyond the Rhine.

‘Barbarians,’ he muttered to himself, with a shake of his head. He was used to the spit and polish of the Praetorian cohorts and had resented being ordered to Gaul to take charge of the latest shipment of silver coin from the imperial mint. After so many years of service as a guardsman, Balbus had very fixed ideas of how a soldier should appear and if he had been posted to a cohort of German auxiliaries, the very first thing he would have done would be to order them to shave off those wretched beards and look like proper soldiers.

Besides, he was missing the comforts of Rome.

Tribune Balbus was typical of his rank. He had joined the Praetorians and served in Rome, working his way up through the ranks, before taking a transfer to the Thirteenth Legion on the Danube and serving as a centurion for several more years and then applying to return to the Praetorian Guard. A few more years of steady service had led to his present appointment as tribune, in command of one of the nine cohorts of the Emperor’s personal bodyguard. In a few more years Balbus would retire with a handsome gratuity and take up an administrative post in some town in Italia. He had already set his sights on Pompeii where his younger brother owned a private bathhouse and gymnasium. The town was on the coast with fine views of the bay of Neapolis and had a decent set of theatres as well as a fine arena, surrounded by taverns selling cheap wine. There was even the prospect of an occasional brawl with men from the neighbouring town of Nuceria, he mused wistfully.

Behind the first five sections of auxiliaries came the four wagons, heavy vehicles drawn by ten mules each. A soldier sat on the bench beside each of the drivers and behind them stretched the goatskin covers, tightly tied over the locked chests resting on the beds of the wagons. There were five chests in each wagon, each containing one hundred thousand freshly minted denarii - two million in all, enough to pay an entire legion for a year.

Balbus could not help a moment of brief speculation about what he could do with such a fortune. Then he dismissed the whimsy. He was a soldier. He had given his oath to protect and obey the Emperor. His duty was to see that the wagons reached the treasury in Rome. Balbus’s lips tightened as he recalled that some of his fellow Praetorians had a somewhat more flexible understanding of the concept of duty.

It was less than ten years ago that members of the Praetorian Guard had murdered the previous Emperor and his family. True, Gaius Caligula had been a raving madman and tyrant, but an oath was as solemn a commitment as Balbus could think of. He still disapproved of the removal of Caligula, even though the new Emperor chosen by the Praetorians had proved to be a rather better ruler. The accession of Claudius had been a confused affair, Balbus recalled. Those officers who had murdered his predecessor had intended to return power to the Roman senate. However, once the rest of their comrades realised that no emperor meant no Praetorian Guard, with all the privileges that went with the job, they swiftly cast around for a successor to the throne, and came up with Claudius. Infirm and stammering, he was hardly the ideal figurehead for the greatest empire in the known world, but he had proved himself a generally fair and effective ruler, Balbus conceded.

His gaze shifted to the last five sections of the German auxiliaries marching behind the wagons. While they might not look like proper soldiers, Balbus knew that they were good in a fight, and their reputation was such that only the most foolhardy of brigands would dare to attack the convoy. Anyway, the danger, such as it was, had passed as the convoy descended on to the broad flat valley of the River Po.

He clicked his tongue and pressed his boots into the flanks of his mount. With a brief snort the horse lurched forward into a walk and Balbus steered it back on to the road, passing the leading ranks of auxiliaries and their commander, Centurion Arminius, until he had resumed his position at the head of the convoy. They had made good time. It was not yet noon and they would reach Picenum within the hour, there to await the Praetorian escort if it had not already reached the town.

They were still some two miles from Picenum when Balbus heard the sound of approaching horses. The convoy was passing through a small forest of pine trees whose sharp scent filled the cold air. An outcrop of rock a short distance ahead obscured the road beyond. Balbus instinctively recalled his days on the Danube where the enemy’s favourite trick was to trap Roman columns in similar confined settings. He reined in and threw his hand up.

‘Halt! Down packs!’

As the wagons rumbled to a standstill, the German auxiliaries hurriedly set down their marching yokes, laden with kit, on to the side of the road and closed ranks at the head and tail of the convoy. Balbus passed the reins into his left hand, ready to draw his sword, and glanced round into the shadows beneath the trees on either side. Nothing moved. The sound of hoofbeats grew louder, echoing off the hard surface of the paved road and the rocks. Then the first of the riders came into view round the bend, wearing the red cloak of an officer. His crested helmet hung from one of the saddle horns. Behind him rode another twenty men in the mud-spattered white cloaks of Praetorian Guard rankers.

Balbus puffed his cheeks and let out a sharp sigh of relief. ‘At ease!’

The auxiliaries lowered their shields and the shafts of their spears, and Balbus waited for the riders to approach. Their leader slowed his horse to a trot and then to a walk for the last fifty paces.

‘Tribune Balbus, sir?’

Balbus looked closely at the other officer. The face was familiar.

‘What is the correct challenge, Centurion?’ he demanded.

‘The grapes of Campania are ripe to pick, sir,’ the other man replied formally.

Balbus nodded at the phrase he was expecting to hear. ‘Very well. You were supposed to wait for us at Picenum, Centurion …’

‘Gaius Sinius, sir. Centurion of the Second Century, Eighth Cohort.’

‘Ah yes.’ Balbus vaguely recalled the name. ‘So, what are you doing out on the road?’

‘We reached Picenum yesterday, sir. Place was like a ghost town. Most of the people had gone to a nearby shrine for some local festival. I thought we would ride out and meet you, and your boys there.’ He gestured towards the German auxiliaries.

‘They’re not mine,’ Balbus growled.

‘Anyway, we saw you approaching the town, sir, and, well, here we are. Ready to escort the wagons back to Rome.’

Balbus regarded the centurion silently for a moment. He liked soldiers who stuck to the letter of their orders and was not sure that he approved of Sinius and his men meeting them here on the road instead of in the town, as arranged. Clear plans for the delivery of the silver had been made in Rome some two months earlier and all concerned should obey their instructions. The moment officers began to play free and easy with their orders, plans began to fall apart. He resolved to have a word with Sinius’s commanding officer when they returned to the Praetorian camp just outside the walls of Rome.

‘Centurion Arminius!’ Balbus called over his shoulder. ‘On me!’

The officer in charge of the German auxiliaries hurried forward. He was a tall, broad-shouldered individual whose scale armour just about fitted his muscular torso. He looked up at the tribune, his beard almost flame-red in the sunshine.

‘Sir?’

Balbus nodded to the horsemen. ‘The escort from Rome. They’ll protect the wagons from here. You and your men can turn back towards Narbonensis at once.’

The German pursed his lips and replied in heavily accented Latin. ‘We were supposed to make the handover in Picenum, sir. The lads were hoping to enjoy themselves in the town for the night before we headed back.’

‘Yes, well, that’s not necessary now. Besides, I doubt the locals will take kindly to being invaded by a small horde of Germans. I know what your men are like when they get some drink inside ‘em.’

Centurion Arminius frowned. ‘I’ll see to it that they don’t cause any trouble, sir.’

‘Nor will they. I’m ordering you to turn round and march back to Gaul at once, d’you hear?’

The other man nodded slowly, his bitterness quite clear. Then, with a curt nod to his superior he turned and strode back to the convoy. ‘Take up your packs! Make ready to march! It’s back to Gaul for us, boys.’

Some of his men groaned and one swore a loud oath in his native tongue, drawing a sharp rebuke from the centurion.

Balbus glanced at Sinius and spoke softly. ‘Can’t have a bunch of hairy-arsed barbarians imposing themselves on decent folk.’

‘Indeed not, sir.’ Sinius nodded. ‘Bad enough that the Germans have been tasked with guarding the mint and the silver convoys as it is. That should be work for proper soldiers, legionaries, or a cohort of the Guard.’

‘Seems that we are not to be trusted by the Emperor,’ Balbus said ruefully. ‘Too many senior officers playing at politics in recent years. And this is what the rest of us have to put up with. Anyway, there’s nothing we can do about it.’ He drew himself up in his saddle. ‘Have your men form up either end of the wagons. As soon as the auxiliaries are out of the way we can proceed.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Centurion Sinius saluted and turned away to call out the orders to his men. As the Germans grumpily formed a single column beyond the wagons, the mounted men eased their horses into place and soon the two small forces were ready to part company. Balbus approached Centurion Arminius to issue his parting instructions.

‘You’re to return to Narbonensis as swiftly as possible. Since I won’t be there to keep watch on your men, don’t let them cause any trouble in any settlements you pass through on the way back. Understand?’

The centurion pressed his lips together in a tight line and nodded.

‘Then you can be off.’

Without waiting for a response, Balbus turned his horse in the other direction and trotted back to the head of the small column where Centurion Sinius was waiting. He waved his arm forward and gave the order for horsemen and wagons to advance. With a crack of the reins from the drivers, the wagons began to move with a clatter and deep rumble from the heavy iron-rimmed wheels. The clop of the hoofs of mules and horses added to the din. Balbus rode on without looking back until he reached the rocky outcrop. Then he glanced round and saw the rear of the auxiliary column a quarter of a mile down the road, tramping back towards Gaul.

‘Good riddance,’ he muttered to himself.

The wagons, with their new escort, followed the road round the rocks and the route resumed its straight direction, through another quarter of a mile of pine trees, towards Picenum. Now that he was well clear of the German troops Balbus felt his mood improve. He slowed his horse until he was riding alongside Centurion Sinius.

‘So, what’s the latest news from Rome?’

Sinius thought for a moment and replied with an amused smile. ‘The Emperor’s new squeeze continues to tighten her grip on the old boy.’

‘Oh?’ Balbus frowned at the coarse reference to the Empress.

‘Yes. Word round the palace is that Agrippina has told Claudius to get rid of his mistresses. Naturally, he isn’t so keen. But that’s the least of his worries. You know that kid of hers, Lucius Domitius? She’s putting it about that the boy is going to be adopted by Claudius.’

‘Makes sense,’ Balbus responded. ‘No point in making the lad feel left out.’

Sinius glanced at him with an amused smile. ‘You don’t know the half of it, sir. Agrippina’s openly pushing Claudius to name young Lucius as his heir.’

Balbus raised his eyebrows. This was a dangerous development; the Emperor already had a legitimate heir, Britannicus, his son by his first wife, Messallina. Now there would be a rival to the throne. Balbus shook his head. ‘Why on earth would the Emperor agree to do that?’

‘Maybe his mind is growing weak,’ Sinius suggested. ‘Agrippina claims that she only wants Britannicus to have a protector and who better for the job than his new big brother? Someone to look out for his interests after Claudius has popped off. And that day ain’t so far off. The old boy’s looking thin as a stick and frail with it. So, once he goes, it looks like the Praetorians are going to have young Lucius Domitius as their new employer. Quite a turn-up, eh?’

‘Yes,’ Balbus replied. He fell silent as he considered the implications. As an infant the Emperor’s son, Britannicus, had been popular with the Praetorian Guard; he used to accompany his father on visits to the camp, wearing a small set of armour of his own and insisting on taking part in the drilling and weapons practice, to the amusement of the men. But the infant had become a boy and these days attended to his studies. Now young Britannicus was going to have to compete for the affection of the Praetorians.

‘There’s more, sir,’ Sinius said softly, glancing over his shoulder as if to make sure that his men did not overhear. ‘If you would care to know it.’

Balbus looked at him sharply, wondering just how far he could trust the other officer. In recent years he had seen enough men put to death for not guarding their tongues and he had no wish to join them. ‘Is there any danger in hearing what you have to say?’

Sinius shrugged. ‘That depends on you, sir. Or, more accurately, it depends on where your first loyalty lies.’

‘My first and only loyalty is to my Emperor. As is yours, and all the men in the Praetorian Guard.’

‘Really?’ Sinius looked at him directly and smiled. ‘I would have thought a Roman would be loyal to Rome first.’

‘Rome and the Emperor are the same,’ Balbus replied tersely. ‘Our oath is equally binding to both. It is dangerous to say different, and I’d advise you not to raise the issue again.’

Sinius scrutinised the tribune for a moment and then looked away. ‘No matter. You are right, of course, sir.’

Sinius let his mount drop back until he was behind his superior. The convoy reached the end of the pine trees and emerged into open country. Balbus had not passed any other travellers since dawn and could see none ahead in the direction of Picenum. Then he recalled what Sinius had said about the festival. A short distance ahead the road descended into a slight fold in the landscape and Balbus stretched up in his saddle as he caught sight of movement amid some stunted bushes.

‘There’s something ahead,’ he said to Sinius. He raised his arm and pointed. ‘See? About a quarter of a mile in front, where the road dips.’

Sinius looked in the direction indicated and shook his head.

‘Are you blind, man? There’s clearly something moving there. Yes, I can make it out now. A handful of small carts and mules among the bushes.’

‘Ah, now I have them, sir.’ Sinius stared into the dip a moment and then continued, ‘Could be a merchant’s train in camp.’

‘At this time of day? This short a distance from Picenum?’ Balbus snorted. ‘I don’t think so. Come, we need a closer look.’

He urged his mount forward, clopping down the road towards the bushes nestling in the dip. Sinius beckoned to the leading section of horsemen to follow him and set off in the wake of his superior. As Balbus drew nearer he realised that there were several more carts than he had first thought and now he could see a handful of men crouching down between the bushes. The anxiety he had felt shortly before returned to prick the back of his scalp with icy needles. He reined in a hundred paces from the nearest of the men and their carts to wait for the others to catch up.

‘I don’t like the look of this. Those scoundrels are up to no good, I’ll be bound. Sinius, ready your men.’

‘Yes, sir,’ the centurion replied in a flat tone.

Balbus heard the rasp of a sword being drawn from its scabbard and he took a tighter grip of his reins as he prepared to lead the mounted guardsmen forward.

‘I’m sorry, sir,’ Sinius said softly as he plunged his sword into the tribune’s back, between the shoulder blades. The point cut through the cloak and tunic and on through the flesh and bone into the spine. Balbus’s head jerked back under the impact and he let out a sharp gasp as his fingers spread wide, half clenched like claws, releasing his grip on the reins. Sinius gave a powerful twist to the blade and then ripped it free. The tribune collapsed forward between his saddle horns, arms hanging limply down the flanks of his horse. The animal started in surprise and the movement dislodged the tribune from his saddle. He fell heavily to the ground, rolling on to his back. He stared up, eyes wide open as his mouth worked feebly.

Sinius turned to his men. ‘See to the drivers of the wagons and then bring them up to the carts.’ He looked down at the tribune. ‘Sorry, sir. You’re a good officer and you don’t deserve this. But I have my instructions.’

Balbus tried to speak but no sound escaped his lips. He felt cold and, for the first time in years, afraid. As his vision began to blur, he knew he was dying. There would be no quiet life for him in Pompeii and he felt a passing regret that he would never again see his brother. Swiftly the life faded from his eyes and they stared up fixedly as he lay still on the ground. Further down the road there were a few surprised cries that were quickly cut off as the wagon drivers were ruthlessly disposed of. Then the wagons and the mounted men continued towards the waiting carts. Sinius turned to a large man close behind him and indicated the tribune’s body. ‘Cestius, put him and the others on one of the wagons. I want two men to ride ahead and keep watch. Another two to go back to the bend in the road and make sure those auxiliaries don’t pull a fast one and turn round to take some unofficial leave in Picenum.’

The men with the carts emerged from the bushes and formed them into a line beside the road. Under Sinius’s instructions, the chests were quickly unloaded from the wagons, one to each of the carts. As soon as they were secured, they were covered with bales of cheap cloth, sacks of grain, or bundles of old rags. The traces were removed from the mule teams on the wagons and the animals were distributed among the carts to haul the additional burden. Once empty, the wagons were heaved deep into the bushes and their axle caps knocked out and the wheels removed from the axles so that they collapsed down, out of sight of the road. The bodies were taken further into the scrub and tossed into a muddy ditch before being covered over with brush cut from the bushes. Finally the men gathered around the carts as Sinius and a handful of others cut some more brush to cover the gaps in the bushes where the wagons had passed through and to sweep the tracks in the grass. Thanks to the frost there were no telltale ruts in the ground.

‘That’ll do,’ Sinius decided, tossing his bundle of twigs aside. ‘Time to change clothes, gentlemen!’

They hurriedly removed their cloaks and tunics and swapped them for a variety of civilian garments in a range of styles and colours. Once the uniforms were safely tucked away in bundles behind their saddles, Sinius looked the men over. He nodded in satisfaction; they looked enough like the merchants and traders who regularly passed along the roads between the towns and cities of Italia.

‘You have your instructions. We’ll leave here in separate groups. Once you get beyond Picenum, take the routes you have been given back to the warehouse in Rome. I’ll see you there. Watch your carts carefully. I don’t want any petty thieves stumbling on the contents of these chests. Keep your heads down and play your part and no one will suspect us. Is that clear?’ He looked round. ‘Good. Then let’s get the first carts on the move!’

Over the next hour the carts left the dip in the road singly, or in groups of two or three at irregular intervals, intermixed with the horsemen. Some made for Picenum, others branched off at the road junction before the town, passing to the west or east and following an indirect route to Rome. Once the last cart was on its way, Sinius took a final look around. There were still some tracks left by the carts and the hoofs of the mules and horses, but he doubted that they would attract attention from travellers on their way to or from Picenum.

With a brief nod of satisfaction, Sinius steered his horse on to the road and walked it unhurriedly towards the town. He paid his toll to the guards on the town gate and stopped at a tavern to have a bowl of stew and a mug of heated wine before continuing his journey. He left the town’s south gate and took the road to Rome.

It was late in the afternoon when he saw a small column of horsemen in white cloaks riding up from the south. Sinius pulled the hood of his worn brown tunic up over his head to hide his features and raised a hand in greeting as he passed by the Praetorian guardsmen riding to meet the convoy from Narbonensis. The officer leading the escort haughtily ignored the gesture and Sinius smiled to himself at the prospect of the man having to explain the disappearance of the wagons and their chests of silver when he reported to his superiors in Rome.

CHAPTER TWO

Ostia, January, AD 51

The rough sea was grey, except where the strong breeze lifted veils of white spume from the crests of waves as they rolled in towards the shore. Above, the sky was obscured by low clouds that stretched out unbroken towards the horizon. A light, cold drizzle added to the depressing scene and soon soaked Centurion Macro’s dark hair, plastering it to his scalp as he gazed out over the port. Ostia had changed greatly since the last time he had been there, a few years earlier on his return from the campaign in Britannia. Then the port had been an exposed landing point for the transhipment of cargo and passengers to and from Rome, some twenty miles inland from the mouth of the River Tiber. A handful of timber piers had projected from the shore to provide for the unloading of imports from across the empire. A somewhat smaller flow of exports left Italia for the distant provinces ruled by Rome.

Now the port was in the throes of a massive development project under the orders of the Emperor as part of his ambition to boost trade. Unlike his predecessor, Claudius preferred to use the public purse for the common good, rather than absurd luxuries. Two long moles were under construction, stretching like titanic arms to embrace the waters of the new harbour. The work continued without let up through every season of the year and Macro’s gaze momentarily rested on the miserable chain gangs of slaves hauling blocks of stone across wooden rollers out towards the end of the moles where they were pitched into the sea. Block by block they were building a wall to protect the shipping from the water. Further out, beyond the moles, stood the breakwater. Macro had been told by the owner of the inn where he and his friend, Cato, were staying that one of the largest ships ever built had been loaded with stones and scuttled to provide the foundations of the breakwater. More blocks of stone had been dropped on to the hull until the breakwater had been completed and now the lower levels of a lighthouse were under construction. Macro could just make out the tiny forms of the builders on the scaffolding as they laboured to complete another course.

‘Sooner them than me,’ Macro mumbled to himself as he pulled his cloak tighter around his shoulders.

He had taken this walk along the shore every morning for the last two months and had followed the progress of the harbour construction with less and less interest. The port, like so many ports, had its complement of boisterous inns close to the quays to take advantage of the custom of freshly paid sailors at the end of a voyage. For most of the year there would have been plenty of interesting characters for Macro to enjoy a drink with and swap stories. But few ships put to sea in the winter months and so the port was quiet and the inns frequented by only a handful of characters in need of drink. At first Cato had been willing enough to join him for a few cups of heated wine but the younger man was brooding over the knowledge that the woman he intended to marry was a day’s march away in Rome and yet the orders they had received from the imperial palace strictly forbade Cato from seeing her, or even letting her know that he was staying in Ostia. Macro felt sympathy for his friend. It had been nearly a year since Cato had last seen Julia.

Before arriving in the port, Macro and Cato had been serving in Egypt where Cato had been obliged to take command of a scratch force of soldiers to repel the invading Nubians. It had been a close-run thing, Macro reflected. They had returned to Italia in the full expectation of being rewarded for their efforts. Cato had richly deserved to have his promotion to prefect confirmed, as Macro deserved his pick of the legions. Instead, after reporting to Narcissus, the imperial secretary, on the island of Capreae, they had been sent to Ostia to await further orders. A fresh conspiracy to unseat the Emperor had been uncovered and the imperial secretary needed Macro and Cato’s help to deal with the threat. The orders given to them by Narcissus had been explicit. They were to remain in Ostia, staying at the inn under assumed names, until they were given further instructions. The innkeeper was a freedman who had served in the Emperor’s palace in Rome before being rewarded with his freedom and a small gratuity which had been enough to set him up in business in Ostia. He was trusted by the imperial secretary to look after the two guests, and not ask any questions. It was imperative that their presence was kept secret from anyone in Rome. Narcissus had not needed to name Julia Sempronia. Cato had taken his meaning well enough and contained his frustration for the first few days. But then the days stretched into a month, then two, and still there was no further word from Narcissus and the young officer’s patience was stretched to the limit.

The only information that Narcissus had volunteered was that the plot against the Emperor involved a shadowy organisation of conspirators who wanted to return power to the senate. The same senate which had been responsible for leading the Republic into decades of bloody civil war following the assassination of Julius Caesar, Macro thought bitterly. The senators could not be trusted with power. They were too inclined to play at politics and paid scant regard to the consequences of their games. Of course there were a few honourable exceptions, Macro mused. Men like Julia’s father, Sempronius, and Vespasian, who had commanded the Second Legion in which Macro and Cato had served during the campaign in Britannia. Both good men.

Macro took a last look at the slaves working on the breakwater and then pulled up the hood of his military cloak. He turned and made his way back along the coastal path towards the port. There, too, was evidence of the redevelopment of Ostia. Several large warehouses had sprung up behind the new quay and yet more were under construction in the area where the old quarter of the port had been razed to make way for the new building projects. Macro could see that it would be a fine modern port when the work was done. Yet more proof of Rome’s wealth and power.

The path joined the road leading to the port and the iron studs on the soles of Macro’s army boots sounded loudly on the paved surface. He passed through the gate with a brief exchange of nods with the sentry who knew better than to demand the entrance toll from a legionary. One of the perks of being a soldier was exemption from some of the petty regulations that governed the lives of civilians. Which was only fair, Macro thought, since it was the sacrifice of the soldiers that made the peace and prosperity of the Empire possible. Apart from the idle tossers in cushy garrison postings in quiet backwaters like Greece, or those preening twats in the Praetorian Guard. Macro frowned. They were paid half as much again as the men in the legions, yet all they had to do was dress up for the odd ceremony and see to the efficient disposal of those condemned as enemies of the Emperor. The chances of any active service were slight. That said, Macro had seen them in action once, back in Britannia during the Emperor’s brief trip to claim credit for the success of the campaign. They had fought well enough then, he admitted grudgingly.

The blocks of apartments lining the street, three or four storeys high, crowded the already wan daylight and imposed a chilly gloom along the route leading into the heart of the town. Reaching the junction where the streets radiated out to the other districts of Ostia, Macro turned right into the long thoroughfare that ran through the heart of the port where the main temples, plushest baths and the Forum crowded upon each other as if jostling to be the most prestigious establishment. It was market day and the main street was busy with merchants and municipal officials hurrying about their business. A line of slaves, chained at the ankle, on their way to the holding pens of the slave market shuffled along the edge of the street under the watchful eye of a handful of burly guards armed with clubs. Macro passed through the Forum, which extended across both sides of the street, and then turned into a side street where he saw the imposing columned facade of the Library of Menelaus where he had agreed to meet Cato. The library had been gifted to Ostia by a Greek freedman who had made his fortune importing olive oil. It was well stocked with an eclectic range of books that were arranged on shelves in an equally eclectic manner.

Macro eased his hood back as he stepped up from the street and ascended the short staircase to the library’s entrance. Just inside the doorway a clerk sat at a plain wooden desk, warmed by the flames of a brazier. His eyes narrowed suspiciously at the sight of a soldier.

‘May I be of any assistance, sir?’

Macro wiped the moisture from his brow and nodded. ‘Looking for someone. A soldier, like me.’

‘Really?’ The clerk arched an eyebrow. ‘Are you certain this is the place, sir? It is a library.’

Macro stared at him. ‘I know.’

‘Might I suggest, sir, that you would have better luck looking for your comrade in one of the inns close by the Forum. I believe that those sorts of establishments are more popular with soldiers than this library.’

‘Trust me, my friend arranged to meet me here.’

‘Well, it’s not where soldiers usually meet, sir,’ the clerk persisted, tersely.

‘True, but then my friend is not your usual military man.’ Macro smiled. ‘So, have you seen him? Just answer the question, eh? No need to look down your nose at me, not if you like it the way it is.’

The clerk realised that this stocky, tough-looking visitor was not going to be fobbed off. He cleared his throat and reached for a stylus and waxed slate, as if to imply that he had been interrupted in the process of carrying out some complex and vital bureaucratic task. ‘I only came on duty a short while ago, sir. If your friend is here, he must have already entered because I have not seen him and have no idea where he might be. I suggest you go and look for him.’

‘I see,’ Macro replied evenly. He stood his ground for a moment and then leant forward across the desk and let the hem of his cloak drip down on to the clerk’s tablet. The clerk froze, then looked up anxiously.

‘Sir?’

‘A parting thought,’ Macro growled. ‘There’s no need for the surly treatment, my lad. You try it on again and I might mistake your nice neat little library for a very rough and ready inn, if you take my meaning.’

The clerk swallowed. ‘Yes, sir. My apologies. Please feel free to enjoy the facilities of the library as you wish.’

‘There!’ Macro leant back with a pleasant smile. ‘Just as easy to be polite as to act like a complete cunt, eh?’

The clerk nervously glanced about to see if any of his colleagues were in view, but he was alone. He looked warily at the soldier in front of his desk. ‘Yes, sir. As you say.’

Macro turned away and rubbed his hands together to warm them up. He had an abiding hatred of the petty officials of the world who seemed to serve no other purpose than to hinder those who actually had useful acts to perform.

The library had a large entrance hall with two doors leading off either side and another directly opposite the entrance. After a brief pause, Macro made for the middle way, his footsteps echoing off the high walls. He entered a long room lined with shelves which were filled with scrolls. The ceiling, rising some thirty feet from the tiled floor, had been painted with nautical scenes which were lit by narrow windows high up in the walls. A line of tables and benches ran down the centre of the library’s main room and since it was still early on a cold morning, there were only three men present, two older men hunched over a scroll as they engaged in a muted discussion, and the unmistakable slender figure of Cato in his military cloak. He sat at the far end of the room, where a faint shaft of light provided barely adequate illumination for the broad sheets of papyrus that lay before him.

The loud clatter of Macro’s boots caused the two old men to break off their discussion and look up with a frown at the new arrival who had disrupted the usual quiet of the library. Although Cato must have heard the sound of his friend’s boots, he continued reading until Macro was almost upon him and then placed his finger on the papyrus to mark his place and looked up. His face was gaunt and he regarded Macro without a flicker of expression as he sat down on the bench opposite Cato. The younger officer had received a severe wound to his face while they were in Egypt and now a white line of scar tissue stretched from his forehead, across his brow and down his cheek. It was quite a dramatic scar but it had not really disfigured his features. A mark to be proud of, Macro thought. Something that would distinguish Cato from the other fresh-faced officers serving the Emperor, and one that would single him out as the seasoned veteran he had become since joining the Second Legion as a weedy recruit some eight years earlier.

‘Found what you’re looking for?’ Macro nodded at the sheets in front of Cato, then gestured to the laden shelves lining the walls. ‘More than enough reading matter to keep you busy, eh? Should help to pass the time.’

‘Until what, I wonder.’ Cato raised his spare hand and lightly rubbed his cheek where the scar ended. ‘We’ve heard nothing from Narcissus for nearly a month now.’

Cato had sent a message to the imperial secretary via the innkeeper, requesting to know why he and Macro had to remain in Ostia. The reply had been terse and simply told them to wait. Cato’s boredom at the enforced stay in the port alternated with acute anger that he was being kept from seeing Julia. Even so, he was tormented by the prospect of her reaction to his scar. Would she accept it and take him into her arms again? Or would she recoil in disgust? Worst of all, Cato feared that she would pity him and offer herself to him on that basis. The thought sickened him. Until he saw her again he could not know her response. Nor could he prepare her for the encounter since Narcissus had forbidden him from contacting her.

‘What are you reading there?’ Macro broke into his thoughts.

Cato focused his mind. ‘It’s a copy of the gazette from Rome. I’ve been catching up on events in the city over recent months to see if there’s any hint of what it is that Narcissus needs us for.’

‘And?’

‘Nothing that springs out. Just the usual round of ceremonies, announcements of appointments and births, marriages and deaths of the great and good. There was a mention of Senator Sempronius. He was commended by the Emperor for putting down the slave revolt in Crete.’

‘No mention of our part in that, I suppose,’ Macro mused.

‘Alas, no.’

‘Well, there’s a surprise. Anything else of note?’

Cato glanced down at the sheets in front of him and shook his head. ‘Nothing significant, unless …’ He shuffled through the sheets, scanning them briefly, then pulled one out. ‘Here. A report dated two weeks ago announcing that one of the Guard’s officers had been waylaid by brigands and killed near Picenum. The brigands have not been found … He leaves behind a grieving widow and young son, et cetera.’ Cato looked up. ‘That’s all.’

‘Doesn’t sound like it has anything to do with our being here,’ Macro said.

‘I suppose not.’ Cato sat back and stretched his arms out as he yawned widely. When he had finished, he leant on his elbows and stared at Macro. ‘Another day in the wonderful town of Ostia then. What shall we do for entertainment? Nothing on at the theatre. It’s too cold to go to the beach and swim. Most of the bathhouses are closed until trade picks up in the spring and our friend, Spurius the innkeeper, refuses to light a fire to warm his place until the evening.’

Macro laughed. ‘My, you are in a miserable mood!’ He thought a moment and then his eyebrows rose. ‘Tell you what. According to Spurius there’s some new stock at that brothel down by the Baths of Mithras. Want to go and see what’s on offer? Something to keep us nice and warm. What do you say?’

‘It’s tempting. But I’m not in the mood.’

‘Bollocks. You’re saving yourself for that girl, aren’t you?’

Cato shrugged. The truth was he did not relish the prospect of visiting the disease-riddled whores who served the townsmen and passing sailors. If he caught anything off them then it would ruin his prospects of any happy union with Julia. ‘You go, if you really want to. I’m heading back to the inn for a bite, then I’m going to settle down for a read.’

‘A read,’ Macro repeated blankly. ‘What have you got in your veins, lad? Blood, or thin soup?’

‘Either way, I’m staying in our room and reading. You can do what you like.’

‘I will. Just as soon as I’ve eaten something to get my strength up.’

The benches scraped back as the two soldiers rose to their feet. Cato swept the gazettes together and returned them to a shelf before he and Macro marched out of the library, their footsteps disturbing the other two men once again.

‘Shhh!’ One of them raised a finger to his lips. ‘This is a library, you know!’

‘Library!’ Macro sneered. ‘It’s a whorehouse of ideas, that’s what. The only difference is that a library will never leave you with a nice warm glow inside, eh?’

‘Shocking!’ the man expostulated. He turned to Cato. ‘Sir, please be so good as to remove your companion from the premises.’

‘He needs no urging, believe me. Come, Macro.’ Cato tugged his arm and steered his friend towards the doorway.

Spurius’s cook, an antique sailor who had lost his leg in an accident, served them a thin stew of barley and chunks of meat that might have come from a highly seasoned lamb shank, but it was hard to be certain as it had lost any flavour it had once had and was the texture of damp tree bark. But it was warm and managed to assuage the soldiers’ appetite. When Cato asked for some bread, the cook scowled, stumped off, and returned with a stale loaf which he set down on the table with a thud.

‘Here! Spurius!’ Macro bellowed, startling the four other customers of the inn. Spurius was at the bar arranging his cheap clay cups on the shelves behind the counter. He turned round irritably and hurried over to the table.

‘What is it? And do you mind keeping your voice down?’

Macro gestured towards the bowl of stew, which was still a third full. ‘I may be hungry enough to eat this swill but I draw the line at bread that I would not even force a bloody pig to eat.’ He picked up the loaf and slammed it down on the table top. ‘Hard as a rock.’

‘So soak it in the stew. It’ll soften up soon enough,’ Spurius suggested in a helpful tone.

‘I want good bread,’ Macro replied firmly. ‘Freshly baked. And I want it now.’

‘Sorry, there’s none available.’

Macro eased his stool back. He continued in a lower voice to make sure that the other customers would not overhear. ‘Look, you’ve been told to look after us and no doubt you’re being paid well enough to put us up and feed us.’

‘I’m being paid a pittance for the pair of you,’ Spurius grumbled. ‘Or at least I will be when you leave and Narcissus settles up. Meanwhile you’re eating into my profits.’

Macro smiled. ‘That snake Narcissus never gives up more than he has to and is as likely to cheat you as he is to honour his word, as we’ve found out to our cost on more than one occasion.’

‘Macro, that’s enough,’ Cato warned him. ‘We don’t talk about our business.’

Macro turned to stare hard at him, and then his expression softened. ‘All right. But I don’t take kindly to being left high and dry in Ostia with only this dive for food and shelter. It ain’t right, Cato.’

‘Of course not, but there’s nothing we can do about it.’ Cato turned to the innkeeper. ‘Now then, I know you resent us being foisted on you. We don’t like it either. But in the interests of us getting on with each other and not causing any trouble, I suggest you do something to improve our rations. To start with, I suggest you get my friend the fresh bread he asked for.’

Spurius took a calming breath and nodded slightly. ‘I’ll see what I can find. If you promise not to cause any trouble with the other customers.’

Cato nodded. ‘We promise.’

The innkeeper returned to the counter and had a quiet word with his cook. Cato smiled sweetly at Macro. ‘See what a little bit of reason can achieve?’

Macro sniffed. ‘It has its place. But then I have to say that I have found that the application of force can be equally effective at producing results from time to time.’

‘Not if you don’t want to draw attention to yourself.’

Macro shook his head. ‘I could do with a little attention, Cato. This place is driving me mad. It’s bad enough that we have to sit and wait at Narcissus’s pleasure. But the bastard hasn’t advanced us more than a fraction of the back pay we’re due and we can’t even afford decent food or more comfortable lodgings.’

Cato was silent for a moment. ‘No doubt that’s intended to help make us compliant.’

Before Macro could respond there was a rattle of cart wheels in the street outside and then the sound died away abruptly as the vehicle drew up outside the inn. Spurius hurried to the door, eased it open a fraction, then quickly ducked outside, shutting the door behind him. Macro and Cato heard a brief muted exchange before the cart continued round the building to the rear where there was a small yard with stalls for the horses of travellers stopping at the inn.

‘New customers for this dump,’ Macro mused. ‘Do you think we should warn them off?’

‘Just leave it,’ Cato said wearily. He stared down into his bowl for a moment before reluctantly picking up his spoon to consume some more of the stew. Shortly afterwards, the cook reappeared, looking flustered as he limped over to the table and presented them with a fresh loaf. Macro sniffed and looked at Cato in surprise. ‘Freshly baked!’

He picked it up, tore it in half and thrust a chunk towards Cato before tearing into the warm doughy mass with relish. From the back rooms of the inn came the sound of voices and the scrape of furniture and it was a short while before Spurius emerged through the low door behind the counter. He glanced round at the other customers and then crossed the room to Macro and Cato’s table.

‘What now?’ Macro muttered. ‘I’ll bet the bastard wants to move us out of the room to make way for his new guest.’

‘I don’t think so.’

Spurius leant towards them and spoke very quietly. ‘Follow me.’

Cato and Macro exchanged a quick glance before Cato responded, ‘Why?’

‘Why?’ Spurius frowned. ‘Just come with me, sir. It’ll be clear enough in a moment. I can’t say anything else.’ He made a slight nod towards his remaining customers. ‘If you understand me.’

Macro shrugged. ‘No.’

‘Come on,’ said Cato. ‘Let’s go.’

They left what remained of their meal and rose to follow the innkeeper across the room towards the door that led to the back. The other people in the room could not help eyeing them curiously as they passed by, Cato noted with a faint smile of amusement. Spurius went first, followed by Macro, with Cato last, who had to stoop under the door frame. There was a narrow room beyond, lit by a single oil lamp. By its weak glow Cato could see that the walls were lined with jars of wine and baskets of vegetables, and a net of fresh bread hung from a hook, close to two joints of cured meat. Clearly the innkeeper ate well, even if his customers didn’t. At the far end of the room a door stood slightly ajar and the frame was brightly lit by a fire burning in the next room. Spurius entered the room, followed by Macro who immediately uttered a curse. The room was generously proportioned with a wide table at its centre. A freshly stoked cooking fire crackled beneath the iron grill and provided the room with a rosy light. Seated on the far side of the table was a slender figure in a plain cloak. He looked up from the cheese and bread that had been laid before him and smiled as he saw Macro and Cato.

‘Greetings, gentlemen. It is good of you to join me!’ Narcissus waved them towards the bench opposite him. ‘Or rather, it is good of me to join you.’

‘What are you doing here?’ asked Macro. ‘I had begun to fear that you were going to keep us sitting on our arses forever.’

‘It is a pleasure to see you too, Centurion,’ Narcissus responded smoothly. ‘The waiting is over. Your Emperor needs you again. Now more than ever …’

CHAPTER THREE

Cato responded to the imperial secretary’s greeting with a cold stare. Despite being born into slavery in the imperial palace, Narcissus had worked hard and been set free by Claudius in the years before he had become Emperor. As a freedman Narcissus had a lower social status than even the humblest Roman citizen, but as one of the closest advisers to the Emperor he had power and influence far beyond that of any aristocrat sitting in the senate. It was Narcissus who also controlled the spy network dedicated to sniffing out threats to his master. In this role he had made use of the services of Cato and Macro before, and was about to again, Cato reflected sourly.

Once the innkeeper had brought a jar of wine and three cups, Narcissus dismissed him. ‘That will do for now, Spurius. Make sure that we are not interrupted, nor overheard.’

‘Yes, master.’ Spurius bowed his head and then turned to leave. He paused at the door. ‘Master?’

‘What is it?’

‘About my daughter. Is there any news of her?’

‘Pergilla, wasn’t it? Yes, I’m still trying to persuade the Emperor to grant her freedom. These things take time. You keep your end of the bargain and I’ll do all I can for her.’ Narcissus waved his hand. ‘Now leave us.’

Spurius hurried out and Narcissus waited until the sound of footsteps faded and the door at the far end of the linking room closed behind the innkeeper.

‘He’s a good and faithful servant, but he can be rather demanding at times. Anyway, enough of him!’ Narcissus leant forward and nodded at the jar. ‘Macro, why don’t you pour us all a drink. We should celebrate this reunion of old friends.’

Macro shook his head. ‘The last thing you are is a friend of mine.’

Narcissus stared at him for a moment and then nodded. ‘Very well then, Centurion. I’ll do the honours.’ He leant forward, pulled out the stopper and poured a dark red wine into each of the cups. Then he set the jar down and raised his cup. ‘At least join me in a toast … Death to the enemies of the Emperor.’

Macro had been looking longingly at the wine and with only a brief show of reluctance he picked up the nearest of the cups and repeated the toast. He took a sip and made an appreciative noise. ‘So this is what that tight bastard Spurius has been keeping back from us.’

‘You’ve not been entertained well then, I take it?’ asked Narcissus. ‘Spurius was instructed to make you comfortable.’

‘He did his best,’ said Cato. If the innkeeper was to be believed then he had not been compensated for the imposition of two guests for as many months. Moreover, if Narcissus was using Spurius’s daughter to enforce his will on the innkeeper, Cato was not going to add to the man’s problems. ‘We were given a clean room and fed regularly. Spurius has served you well.’

‘I suppose he has.’ Narcissus glanced at Macro’s surprised expression and then cocked an eyebrow. ‘Though you don’t appear to agree that he has served you particularly well.’

‘We’re soldiers,’ Macro replied. ‘We are used to worse.’

‘So you are. And it is time for you to serve Rome once more.’ Narcissus took a small mouthful of wine and licked his lips. ‘Falernian. Spurius is trying to impress!’

‘I imagine you will be in a hurry to return to the palace,’ said Cato. ‘Best that we get straight to business.’

‘How considerate of you, young Cato,’ Narcissus responded in an icy tone. He set his cup down with a sharp rap. ‘Very well. You recall our last meeting?’

‘On Capreae, yes.’

‘I raised the matter of a new threat posed by the Liberators. Those scum will never rest until the Emperor is disposed of. Naturally, they claim to act in the interests of the senate and people of Rome, but in reality they will plunge Rome back into the dark age of tyrants like Sulla and Marius. The senate would be riven by factions fighting for power. We’d have a civil war on our hands within months of the fall of Claudius.’ Narcissus paused for a moment. ‘The senate had its uses in an age before Rome acquired an empire. Now, only a supreme authority can provide the order that is needed. The fact is that the senators cannot be trusted with the safety and security of Rome.’

Cato laughed drily. ‘And you can be, I suppose.’

Narcissus was silent for a moment, his narrow nostrils flared with disdain. Then he nodded. ‘Yes. I, and those who serve me, are all that stand between order and bloody chaos.’

‘That may be true,’ Cato conceded, ‘but the fact is that the order you claim to protect is almost as bloody from time to time.’

‘There is a price to pay for order. Do you really think peace and prosperity can be maintained without the shedding of a modicum of blood? You two soldiers, of all people, must know that. But what you don’t know is that the wars you wage for Rome don’t end when the battles are over. There is another battlefield, far from the frontier, that goes on, never ending, and that is the fight for order. That is the war that I wage. My enemies are not screaming barbarians. They are smooth-talking creatures lurking in the shadows who seek personal power at the expense of the public good. They may dress their base ambitions up in the robes of principle, but believe me there is no evil they would not countenance to achieve their ends. That is why Rome needs me, and why she needs you. Men like us are her only hope for survival.’ Narcissus paused and helped himself to some more wine, and licked his lips.

‘It’s funny,’ said Cato. ‘When other men act out of self-interest you call it evil. When we do it, we’re patriots.’

‘That is because our cause is just. Theirs is not.’

‘A difference of perspective.’

‘Don’t dignify our enemies with your philosophical abstractions, Cato. Just ask yourself whose Rome you would prefer to live in. Ours, or theirs?’

Macro clicked his tongue. ‘He has a point.’

‘There!’ Narcissus beamed. ‘Even Centurion Macro can see the sense of what I say.’

Macro frowned and cocked an eyebrow. ‘Even Centurion Macro … Thanks.’

Narcissus gave a light laugh and topped up Macro’s cup. ‘I meant no offence. Just to say that the right and wrong of it is abundantly clear to a man of action, such as yourself.’

While Macro reflected on this the imperial secretary moved on hastily. ‘In any case, Cato, there is really very little choice in the matter. While I respect your right to express an opinion, however poorly thought through, you have to do as I say, if you and Macro want to advance your careers, and especially if you want to marry that rather nice daughter of Senator Sempronius.’

Cato lowered his head and slowly ran his fingers through the dark curls of his unkempt hair. Narcissus had them exactly where he wanted them. More than anything, he and Macro wanted to return to the army. Cato needed a promotion that would carry with it membership of the equestrian class. Only that would make his marriage into the family of a senator acceptable.

‘Well, lad,’ Macro interrupted his chain of thought. ‘What about it? Anything to get us out of this place. Besides, it can’t be too bad a job. Nothing more dangerous then we’ve faced already, surely?’

Narcissus pursed his lips but did not say anything.

With a weary sigh Cato raised his head and looked directly at the imperial secretary. ‘What do you want us to do?’

Narcissus smiled slowly, with the air of a man accustomed to having his way. ‘I’ll begin by explaining something of the background to the situation.’ He leant back and folded his fingers together. ‘As you already know, the regime was nearly brought down by the conspiracies perpetrated by Messalina. That woman was pure poison. There was no debauchery that was beneath her. The only thing that matched her wanton lack of morals was her ambition. She knew exactly how to wrap Claudius round her finger. Not only him, but many others, including one of the Emperor’s other advisers, Polybius.’

‘I know the name,’ said Cato. ‘Didn’t he commit suicide?’

‘That’s what he was ordered to do. In the Emperor’s name. There wasn’t even time to appeal to Claudius before he was visited by some Praetorian guardsmen who rather pressed the issue.’

‘The line between murder, execution and suicide has become a little blurred in recent years. Death, one way or another, resolves a political difficulty, or a desire for revenge, or simply comes on a whim from those with the authority to order it. Which is why Messallina could not be permitted to remain in a position where she could exert more influence over the Emperor than his closest advisers. So when she decided to use the Emperor’s absence from Rome to divorce him, marry her lover and then seize power, we had to act. Claudius was here in Ostia, to inspect the progress of the harbour development. That’s when the news reached me. I could see the imminent danger clearly enough and spoke to those who were closest to the Emperor, Callistus and Pallas. It took all our powers of persuasion to get Claudius to accept the truth about Messallina. Then he denied it all, saying it couldn’t be true.’ Narcissus visibly trembled at the memory. ‘So we encouraged him to drink some wine to soften the blow. That was when we presented him with a warrant for her arrest and execution, among a handful of other warrants issued for the arrest of her allies.’

‘You dog!’ Macro commented admiringly. ‘What did the Emperor do when he came to his senses?’

‘He grieved for a month. While the three of us disposed of the other members of Messallina’s conspiracy. The point of all this is to make you aware of how easily the Emperor is gulled, and that makes him, and Rome, vulnerable.’

‘So what’s the story with his new wife?’ asked Macro. ‘Agrippina. She’s his niece, if I recall right.’

‘Oh, yes. And that caused a fine scandal when Claudius announced his choice of new bride to the public. I had to battle to get the senate to pass a measure to remove such a marriage from the incest laws. Fortunately one of the leading senators was keen to ingratiate himself with the Emperor. He picked up the job and pushed the new law through. Even then it was no easy feat, I can tell you.’

Cato had been thinking during the exchange. ‘Whose idea was it to suggest Agrippina?’

There was a brief pause before Narcissus replied in a venomous tone, ‘Pallas. He said we’d have a better chance of avoiding a repeat of the Messallina episode if we chose a bride from within the family. Besides, Pallas has some influence over her. We calculated that we would be able to keep her in line and ensure that Claudius continued to take advice from us.’

‘And has it worked? Is the new Empress taking to her role with the required degree of compliance?’

Narcissus tilted his head to one side. ‘She’s not been much trouble. The only problem is that she came to the marriage with some rather awkward baggage.’

‘Baggage?’

‘Her son. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. At least that is what he used to be called, before she talked the Emperor into adopting him. Now he’s known as Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus. Claudius’s natural son is not taking to the new arrangement. Britannicus refuses to acknowledge his stepbrother and won’t call him Nero. So there’s no love lost there. Those two are going to be scrambling to succeed Claudius when he goes into the shades, or wherever it is that deified emperors go.’

Macro shook his head. ‘Sounds like there’s going to be a right old carve-up when the time comes.’

Cato thought for a moment before he spoke again. ‘But Britannicus is the Emperor’s heir, so surely he is first in line to succeed?’

‘If only it was that clear cut,’ Narcissus replied. ‘Nero is fourteen, four years older than his stepbrother. Britannicus has the additional disadvantage that his mother was Messallina and that puts him under a bit of a cloud as far as his father is concerned. If he should become Emperor then I fear for the enemies of his mother. He’s the kind of boy who would make a priority of revenge.’

Macro smiled. ‘So, there is some justice in life. That prospect must be causing you a few restless nights.’

Narcissus’s expression suddenly hardened. ‘Centurion, if you knew only a fraction of what burdens my mind I doubt whether you would sleep at all. The Emperor is vulnerable to threats from all sides. His health is starting to fail and I must do everything in my power to protect him and ensure that peace and order endure.’

‘And when the old boy dies? What then?’ Macro asked shrewdly.

‘Then we must ensure that the right successor is chosen.’

‘Who do you have in mind?’ asked Cato.

‘I’m not yet certain. Nero and Britannicus are young and each has his own virtues and flaws. When the time comes I, and the Emperor’s other advisers, will make our choice and point Claudius in the right direction when he names his successor.’

Cato pursed his lips briefly. ‘I don’t see what all this has to do with Macro and me. There’s nothing we can do to influence events.’

‘I told you, I felt it necessary to brief you on the wider picture, so that you understand the full gravity of the situation when I tell you what I must ask you and Macro to do.’

The two officers looked at each other quickly then Cato gestured to Narcissus to continue.

The imperial secretary collected his thoughts and spoke in a subdued tone. ‘With the palace divided, the Liberators have decided to act. The key to any change of power in Rome is to have control of the Praetorian Guard. It was the support of the Praetorians that made Claudius’s accession possible. When the Emperor dies, they are the final arbiter when it comes to the question of who wins the throne. Now, if the Liberators can win control of the Praetorians then the question of which of the Emperor’s two sons will succeed him becomes academic. They will be cut down, along with the rest of the imperial family, their servants and allies.’ He paused to let his words sink in. ‘That is why the command of the Guard is split between two prefects and the Emperor’s immediate bodyguard is made up of German mercenaries - men he can trust. However, one of the prefects has been ill for several months, which leaves the Praetorians under the command of the other, Lusius Geta, who is more of a concern. Lately he has been increasing the training of the men, working them hard with regular route marches, weapons exercises and mock battles. Recently the battle training has shifted emphasis. He is now drilling them in street fighting and siege techniques.’

‘Sounds like a conscientious commander to me,’ said Macro. ‘I would be working the men just as hard in his place.’

‘I’m sure you would. But this is not the custom of previous prefects. More worrying still is that most of his officers seem to be fiercely loyal to Geta and hold him in high regard.’ Naricissus opened his hands. ‘You must see that I have reason to regard the man with a degree of suspicion.’

Macro shrugged, but Cato nodded slightly.

‘There’s more. Last month one of the tribunes of the Guard was killed on the road.’

Cato nodded. ‘Balbus.’

‘That’s right. How did you know?’

‘I read of it in the gazette. Not much else for me to do with my time. I gather Balbus was killed by brigands.’

‘That’s the version that was put out. What the report did not mention is that he was in command of a bullion convoy sent from the mint in Narbonensis. The search party found his body stripped by the side of the road, no doubt to make Balbus look like the victim of a robbery. It didn’t take them long to locate the remains of the wagons from the convoy. But the bullion chests were gone. About two million denarii lost in all.’

Macro whistled.

‘Quite. A vast sum, and the thing is, only a handful of men, imperial servants and Praetorians, knew about the convoy. This was an inside job. No question of it. I’ve had those in the know questioned, and some of them put under torture, but my interrogators got nothing out of them. Either they are innocent, or they are tough enough not to crack under pressure.’

‘Perhaps word of the convoy leaked out,’ Cato suggested. ‘Someone overheard or saw something that gave it away.’

‘It’s possible. But I trust my men to be discreet. They know the price for disappointing me will be severe. So that leaves the Praetorians. Either their security is slack, or there are traitors in their ranks. That’s how it seemed to me until a few days ago. Then we had a stroke of good fortune. One of the Praetorians got drunk and started a fight in some drinking hole close to the Great Circus. He was confined to quarters. On closer investigation it was discovered that he had been spending money all day buying drinks for comrades and passers-by. He had also lost a small fortune in silver at the races, and yet he had not drawn any money from his savings at the barracks. I gave orders for him to be released and his centurion put him on fatigues for a month. Two nights ago I ordered my agents to snatch him and take him to a safe house outside the city for questioning. He proved to be a tough customer and more rigorous methods of interrogation were necessary, alas. Before he died he confessed to being involved in the attack on the convoy and he gave up one name. A centurion who is serving in the cohort entrusted with guarding the imperial palace, Marcus Lurco. According to the man, Lurco is one of the leading conspirators. So now we know that there is a faction of traitors in the Praetorian Guard.’

‘Did the Praetorian mention any link to the Liberators?’ asked Cato.

‘He did.’ Narcissus took a breath. ‘The situation is serious. There’s only one reason why they would be after such a fortune. They’re amassing a war chest. Once they have enough, it’s my belief that they’ll use the money to bribe the Praetorian Guard to back them when they attempt to overthrow the Emperor.’

There was a brief silence. Macro drained his cup and poured himself another while trying to look thoughtfully engaged. ‘All of which is very interesting, but what’s this got to do with us?’

‘It’s simple. I need some men on the inside who I can trust completely. I want you and Cato to join the Praetorian Guard, penetrate the conspiracy, identify the leaders and then, if necessary, eliminate them. Oh, and locate and return the stolen bullion.’

Macro stared at him and then laughed. ‘Easy as that. Surely you have agents who are used to all this cloak-and-dagger bollocks? We’re soldiers and wouldn’t have a clue about how to go and stab a man in the back. There has to be someone better than us you can use.’

‘Oh, I have a small circle of men I can rely on. A very small circle, and men I can ill afford to lose. Besides, for this job I need men who can pass as soldiers.’ Narcissus paused and smiled thinly. ‘Let’s not beat about the bush. You two are expendable. Besides, I know you will accept. How can you do otherwise?’

Macro shook his head. ‘We’d be mad to accept such a task.’

‘You have no other choice, given that what you desire is within my power to grant - or withhold, as I see fit.’ His gaze switched to Cato. ‘Is that not so?’

Cato nodded reluctantly. ‘He’s right, Macro. If we want to return to the army and if I’m to have my promotion, what else can we do?’

‘Precisely.’

‘No,’ Macro replied. ‘Think about it, Cato. We’re soldiers. We’re trained to fight. Not to spy, not to play the part of some imperial agent. They’d see through us in an instant. I’m not going to end up with my throat cut and my body dumped in the Great Sewer. Not me. I won’t do it. Nor will you if you have any sense.’

‘This is not some scheme I dreamed up on the road from Rome.’ Narcissus spoke with icy intensity. ‘I have considered the matter carefully and I am certain that you two have a far better chance of succeeding than my agents. You are experienced soldiers and will fit in with the Praetorians where my men would stick out like sore thumbs. You are also virtually unknown in Rome, whereas my men are familiar faces. If I use anyone else then I will have to hire men in from outside the capital, men whose ability I don’t know, and who I have no idea how far I can trust. The truth is, we need each other. If you see this through, I give you my word of honour that you will both be generously rewarded.’

‘I’m not sure your word is good enough,’ said Macro.

‘How do you plan to get us into the Praetorian Guard?’ Cato intervened. ‘If a pair of officers turn up and start asking questions, the opposition are bound to be suspicious.’

‘Of course, that’s why you will be joining the Praetorians as rankers. Two veterans of the Second Legion just returned from Britannia. Your appointment to the Guard is a reward for gallant service against the barbarians. It’s a credible cover story, and it’s close enough to your experience for you not to have to act much. All that will be different is your rank. It shouldn’t be too hard a role to play.’

‘Easy for you to say,’ Macro grumbled. ‘What if we run into anyone we’ve met before?’

‘It’s unlikely. It’s over three years since you were last in Rome, and then you were renting rooms in the Subura while you were on half-pay. No one in the Praetorian Guard knows you. Apart from a handful of my clerks who might remember your faces, you shouldn’t be recognised by anyone at the palace.’

‘What about Senator Sempronius?’ Cato asked. ‘And Julia? If we encounter them our identities will be exposed.’

‘I’ve thought of that.’ Narcissus smiled. ‘I’ve arranged for the senator to conduct an inventory of the Emperor’s estates in Campania. I’ve instructed him to take his daughter with him so that she can enjoy the social scene. It’s a light enough task, but one that will keep them out of the way until spring. By which time I trust that you two will have unearthed the traitors in the Praetorian Guard and any of their accomplices in the city.’

‘There are others who will recognise us. Senator Vespasian for example.’

Narcissus nodded. ‘I’m aware of that. Vespasian has been elected one of the consuls this year and will be busy in the senate.’

‘Vespasian is a consul?’ Macro smiled. ‘Good on him.’

‘While I share your regard for his abilities, I have to say that Vespasian’s elevation to the consulship is something of a concern. He may be more ambitious than I previously gave him credit for.’

‘Oh, come on!’ Macro shook his head. ‘You can’t be suspicious of Vespasian. After all that he has done for the Emperor? Why, if it wasn’t for him then I dare say the campaign in Britannia would have been a disaster. And there was that business with the pirates. He served Claudius loyally.’

‘I know. But it is my job to look for danger signals. Any displays of ambition have to be carefully scrutinised. So, Vespasian is being watched closely.’ Narcissus paused before he continued. ‘It would be most unwise to take the risk of our being seen together, so you will report to me via one of my agents, Septimus. Aside from me, he’ll be the only one in the know. You can meet him at the Vineyard of Dionysus in the Boarium in two days’ time.’

‘How will we know him?’ asked Cato.

Narcissus pulled a ring from the little finger of his left hand and passed it to Cato. ‘Wear this. My agent will have its twin.’

Cato held the ring up to examine it and saw that a design had been artfully carved into the red stone: a depiction of Roma astride a sphinx. ‘Nice.’

‘Of course I’ll have that back once it’s served its purpose.’ Narcissus looked at them both. ‘Well then, any further questions?’

‘Just one.’ Macro leant forward. ‘What happens to us if we decline your kind offer of employment?’

Narcissus fixed him with a cold stare. ‘I haven’t considered that yet. For the very good reason that I cannot imagine you would be so foolish as to refuse the job.’

‘Then you had better start considering.’ Macro sat back and folded his arms. ‘Find some other mugs to do your dirty work. I’m a good soldier. There’ll be an opening for me sometime or other. I can wait.’

‘For how long, I wonder? Perhaps not for as long as I might wish to keep you rotting here.’

Macro’s expression darkened. ‘Fuck you. Fuck you and your nasty little schemes.’ Macro bunched his hands into fists and for a moment Cato was afraid his friend might take it into his head to pulverise the imperial secretary. The same thought occurred to Narcissus who flinched back. Macro glowered at him for a moment then stood up abruptly. ‘Cato, let’s go and get a drink. Some other place. The air’s foul here.’

‘No,’ Cato answered firmly. ‘We have to do it. I’m not staying in Ostia any longer than I can help it.’

Macro stared down at his comrade for a moment and then shook his head. ‘You’re a fool, Cato. This snake will get us killed. Why should we succeed in uncovering the Liberators when the Emperor’s agents have failed all these years?’

‘Nevertheless, I’ll do it. And you’ll come with me.’

‘Bah!’ Macro threw up his hands. ‘I thought I knew you. I thought you were smarter than this. Seems I was wrong. You’re on your own, Cato. I’ll have no part of this.’

Macro strode to the door and wrenched it open, slamming it behind him. Cato heard his footsteps receding with a sinking feeling in his heart. Macro was right about the dangers, and Cato realised that he had little confidence that he could see such a mission through without the tough and dependable Macro at his side. For the first time in many months, he felt a pang of fear. The prospect of facing the Emperor’s shadowy enemies on his own was daunting.

‘I shouldn’t worry about him.’ Narcissus chuckled. ‘Now he’s had a chance to unleash his anger at me, he’ll come round soon enough.’

‘I hope you’re right.’

‘Trust me, I can read almost any man like a scroll. And our friend Macro is a somewhat less challenging read than most. Am I wrong? You know him well enough.’

Cato reflected for a moment. ‘Macro is capable of surprising turns of thought. You should not underestimate him. But yes, I think he’ll come with me. Once he’s had a chance to simmer down and reflect on the fact that you might make his life very difficult. I take it you meant that.’

Narcissus’s thin lips twisted into a faint smile as he rose to leave. ‘What do you think?’

‘Fair enough. But I have one piece of advice for you, if you want this mission to go well.’ Cato paused. ‘Never ever call him a friend to his face again.’

CHAPTER FOUR

The surface of the Tiber was dotted with flotsam and patches of sewage as the barge approached Rome late in the afternoon. A team of mules was towing the vessel against the current and their driver, a skinny, barefoot slave boy, flicked his whip once in a while to keep the pace up. Ahead a thick pall of woodsmoke hung over the city as the inhabitants struggled to stay warm through the dreary winter months, adding the output of the communal fires they were permitted to the smoke of the tanneries, smiths and bathhouses that plied their trade in the capital.

Cato wrinkled his nose as a foul odour swept across the surface of the river, blown by the stiff easterly breeze.