Chapter 20

Feeding

In This Chapter

• The nutrients your plants need

• NPK and other fertilizers

• Side dressings versus top dressings

• Feeding your garden organically

People have been fertilizing plants since the beginnings of agriculture, but we’ve only really known why we do what we do since the early nineteenth century. It was then that the first systematic studies took place on the requirements of plants for nutrients—nitrogen, phosphate, potassium, and so on.

In this chapter, we have another important science lesson. This time it’s about the nourishment plants need to prosper and how gardeners can respond to those needs, including so-called organic approaches. All the substances are essential for every cell in every plant, but given nutrients might play a larger role in certain plant organs and developmental processes.

In this chapter, we also take a close look at the famous NPK trio: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. We get familiar with some of the other important macronutrients and micronutrients, and we find out about the best ways to deliver these essentials to our garden plants.

What Plants Want

Keeping plants properly fed is all about balance. Just as humans and animals need a balanced diet, so do plants. In addition to adequate supplies of water and air, plants require generous portions of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to produce leaves, grow roots, set fruit, and make seeds. And they need these things in specific amounts.

As plants grow, they draw nutrients from the soil. Some of the nutrients are plentiful, with more than enough to keep providing what plants need indefinitely. Other nutrients become depleted. In a natural setting, depleted nutrients are replenished when plants die off and decompose. But in a garden, the plants are harvested and dead plant material is generally cleaned up, so that natural process is short-circuited. It then becomes the gardener’s job to replenish the supply of used-up nutrients.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

We can now name 17 elements essential to the growth of plants, starting with carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen (air and water); then nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (the famous NPK); followed by the familiar calcium, magnesium, sulphur, and iron; through the lesser-known nutrients, including boron, manganese, and zinc; also copper, chlorine, molybdenum, and finally nickel, whose essentiality was confirmed only about 15 years ago.

A Short Course on NPK Fertilizer

The trio of NPK—N = nitrogen, P = phosphorus, and K = potassium—is the basis of all fertilizers. After you commit the following information to memory, you can officially call yourself a gardener.

Just about all commercial fertilizers have labels that give a series of three numbers like 5-10-5 or 10-10-10. These numbers represent the percentages of N (nitrogen), P (phosphorus), and K (potassium), respectively. But the numerical representations are not consistent, logical, or universal. Bear with me. You need to know this stuff.

In the United States, the numbers represent the percentages of elemental nitrogen, phosphorus as phosphate, and potassium as potassium oxide. The fertilizer labeled 5-10-15 contains the equivalent of 5 percent nitrogen, 10 percent phosphate, and 15 percent potassium oxide.

Are you thoroughly confused? Well, don’t go away. It gets worse. The percentages of nutrients, and especially of nitrogen, are only part of the story. Plants regulate themselves in terms of the balance of vegetative growth and reproduction, but too much nitrogen in a readily available form—ammonium or urea—can cause “fertilizer burn” or even turn off fruit set and push excessive vegetative growth.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

The percentages are equivalents because the nitrogen could be present as ammonium, nitrate, or urea, not as elemental N, which is nitrogen gas; the phosphorus as phosphate, bone meal, or other organic form; and the potassium would certainly not be present as potassium oxide, which is caustic.

Give Me an N

Eventually every gardener must become familiar with nitrogen. The big N is one of those really important factors in the health and prosperity of most plants. Nitrogen comes in several common forms.

Nitrate occurs as the mineral sodium nitrate. It’s highly soluble, can be used immediately by plants, is the most expensive form of nitrogen (it comes from mines in Chile), and can be taken up by the plant and stored harmlessly.

Ammonium (similar to household ammonia) is instantly available to the plant, and the plant must convert it to a storage form, which requires an investment of starch. If the plant runs out of stored starch, the ammonium will kill it.

Urea is the most common nitrogenous constituent of urine. Most plants convert it rapidly to ammonium nitrogen, so it has the same dangers. Urea is relatively inexpensive.

Organic nitrogen is made of complex organic compounds that contain nitrogen. These are ideal in that the nitrogen only becomes available as it’s slowly decomposed by soil microorganisms. Urea (which is itself organic) can be converted to less-available forms by various chemical tricks.

Compost Pile

Like nitrates, most ammonium salts are highly soluble and, like nitrates, ammonium nitrogen is readily available to the plant. In fact, the problem with ammonium salts is that they’re too available to plants. If ammonium nitrogen isn’t converted to organic nitrogen, it can become highly toxic.

Finally, there’s atmospheric nitrogen. Eighty percent of the atmosphere is N2 or nitrogen gas. Gaseous nitrogen is not normally available as a nutrient to plants, but nitrogen-fixing bacteria can convert gaseous nitrogen to ammonium, and certain of these bacteria live symbiotically with peas and a few other plants, supplying ammonium to their host in exchange for carbohydrates and other nutrients.

Give Me a P

The chemical symbol for phosphorus is P. Plants absorb this essential as phosphate ion (PO4). Phosphorus is a significant factor in the storage and distribution of energy in plants, so it’s especially important for root development.

Sometimes plant specialists recommend a shot of superphosphate for certain plants. This stuff (a mixture of calcium phosphate and calcium sulfate) is a less-soluble form of phosphate, which makes it available for a longer period of time. It won’t wash away when it rains or when the irrigation system turns on.

Give Me a K

The chemical symbol for potassium is K. Potassium is the third element in the fertilizer formula. Unlike nitrogen and phosphate, potassium does not make strong bonds with other molecules, so it’s always floating around as a free ion. It moves around inside plants to wherever it’s needed most. And because it’s a free ion in the soil, it leaches out easily, especially in sandy soil.

It’s rare to have too much potassium in garden soils, but there can be deficiencies. This often shows up as problems with older leaves. Roots are also susceptible to potassium deficiencies. A soil test can point out whether you need to add potassium.

Most of the K found in commercial fertilizers comes in the form of potassium chloride. Old-time gardeners might still refer to potassium as potash, although this term is somewhat outdated.

Macro and Micronutrients

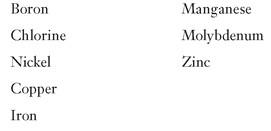

N, P, and K are the macronutrients plants require in the largest amounts. The other macronutrients are carbon, oxygen, calcium, magnesium, hydrogen, and sulphur. But plants need these micronutrients, too:

It’s important to understand that plants require only tiny amounts of these nutrients. But if one element is out of balance, it can affect the availability (the ability of the plant to take in or use) of another one of the elements. For example, if there’s too much magnesium, the plant might have difficulty with calcium uptake. This can result in poor growth, a reduction in seed production, and other symptoms. Conversely, too much calcium can interfere with magnesium absorption.

Most of the micronutrients plants need are present in soil in adequate quantities. However, the combination of high pH and high calcium levels can make a number of the heavy metals unavailable to plants.

Where micronutrients and trace metal deficiencies are common, as in the Southwest, you have a couple options when it comes to getting them to your plants. You can lower the soil pH with gypsum to about 6.0 to 7.0. Or you can add or spray with chelates.

Many commercial fertilizers also include micronutrients.

Compost Pile

One of the leading causes of eutrophication, or the overgrowth of algae in aquatic and marine environments, is fertilizer runoff. The contribution from home gardeners is relatively insignificant when compared to that from agriculture, but it’s still important for home gardeners to mix and apply commercial fertilizers carefully and according to the manufacturer’s directions. Gardeners who work in sandy soil should take extra care, as fertilizer runoff is generally worse from these soil types.

Natural Foods for Plants (the Organic Approach)

When it comes to organic fertilizer, the natural perspective has undeniable advantages. The nutrients from manure, compost, fish heads, and other organic matter are released slowly, which avoids some of the real dangers of overfertilization. There are a number of methods for feeding the garden organically. (Note the earlier cautionary point on urea, which is organic.)

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Here’s an easy equation for converting commercial fertilizer to organic types: 25 pounds commercial 10-10-10 fertilizer roughly equals: 50 pounds cotton seed meal + 15 pounds lambeinite + 50 pounds rock phosphate 60 bushels cow or horse manure 24 bushels chicken, sheep, or rabbit manure

Manure Tea, Anyone?

This is clearly not the tea to serve the ladies! Manure tea is a concoction made from—you guessed it—manure that’s been steeped in water to create a liquid plant fertilizer. The best recipe I’ve found for manure tea is from The Victory Garden Kids’ Book (Globe Pequot Press, 1994). (My good friend Alison Kennedy did the design for the book, and it’s one of my most favorite gardening books.)

To brew your own manure tea, put a shovelful of well-rotted manure in a 5-gallon bucket and fill the bucket with water. Let it stand for a few hours. And then, ta da. It’s ready to use. You can make larger quantities in a big plastic garbage can. Just use the same proportions.

Manure tea is great as a starter food for new seedlings or as an all-purpose fertilizer for the regular feedings you do every 2 or 3 weeks.

Sounds Pretty Fishy

The Wampanoag Indians of Massachusetts, as well as many early Native Americans, dropped a fish head in each planting hole when they sowed their corn, beans, and squash. They were following age-old traditions that were most likely based on someone’s observation that plants grown near dead fish grew better than ones without the fish.

Compost Pile

There’s been concern about a toxic form of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria that’s caused serious health issues in recent years. The problem is related to the manure of ruminating (cud-chewing) animals, but it’s usually caused by contamination of irrigation water, especially where there are high concentrations of animals, like in feed lots. The home gardener who uses well-rotted manure to amend soil is unlikely to risk that kind of contamination. But carefully wash all produce, from any source, before you eat it.

The scientific reason why decomposing fish might be good for crops is because in the breakdown of organic matter like dead fish, there’s the slow release of nutrients like ammonium, nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium that, of course, are the principal nutrients plants require.

Today, instead of stocking up on dead fish, you can use fish emulsion to feed your garden plants. Don’t try making your own unless you have large quantities of fish guts hanging around the house. Instead, look for commercial preparations at garden centers and nurseries.

The Poop on Poop

Manure is one of the best, and of course one of the oldest, organic fertilizers known to man. Cow pies, were, after all, free for the taking down on the farm. Manure from cows, horses, goats, chickens, and rabbits and, more recently, alpacas and llamas is the most commonly used.

Try to use manure that’s free of straw. The microorganisms that help decompose the straw will convert nitrogen to organic forms that would only become available over time. This natural time-released nitrogen is typically a good thing for gardens, but sometimes you want just enough at once to meet plants’ needs.

Avoid using fresh manure on your vegetable garden because the acids in it will actually burn the growing plants. As mentioned earlier, well-rotted manure can be used as a fertilizer. Well-rotted means it’s been allowed to sit and age for several months. If you don’t have your own source of manure, look for bags of processed manure at garden centers and nurseries.

While most herbivores produce suitable manure for gardening purposes, some purists say that stuff from horses works best. The form of nitrogen found in horse manure (called hippuric acid) is released more slowly than that in, say, cow, or sheep manure. But horse manure is more likely to contain viable seeds that could introduce weeds to your garden.

Never use waste from dogs, cats, or humans as a fertilizer. Although human waste (sometimes referred to as night soil) is still commonly used in some parts of the world to fertilize crops, it’s a dangerous practice contributing to some really ugly diseases. Also avoid the use of processed sewage sludge as a fertilizer for edibles. It is a rich food for ornamental plants, but it might contain heavy metals that are toxic.

Garden Guru Says

You can add fresh manure to garden beds in late fall or early winter after everything has died back. Use a pitchfork or a big shovel and pile it on. Then spread it out as evenly as possible. You can either leave it on the surface or give the whole bed a quick till. In the spring, till it thoroughly.

When you use large quantities of cow, sheep, llama, alapca, or goat manure to fertilize your garden, keep in mind, while your garden beds will be rich and friable, there might be a phosphorus deficiency. Cud-chewing animals enlist the aid of microorganisms to extract phosphate from phytins and phytic acid, which can represent most of the phosphate in the plants that cows and others eat. Do a soil test to be sure. If your soil is low in phosphorus, add some superphosphate (0-45-0 fertilizer). About 4 pounds per 1,000 square feet of garden should be enough to get the levels up to par. Or you can use organic bone meal, acidulated bone, or rock phosphate.

The University of Florida IFAS Extension has a valuable publication on organic gardening that includes extensive information on organic fertilizers. The tables on NPK levels in various manures, as well as availability and acidity, are particularly useful. Find it at www.edis.ifas.edu.MG323.

Compost

If ever there were a product that warms my thrifty soul, it’s compost. I love the way we can take otherwise useless kitchen garbage and garden debris and turn it into one of the richest plant foods possible.

I’ve already discussed how to make your own compost in Chapter 8 so I won’t repeat myself here. Turn back to that chapter for a refresher if you need to.

Leaf Mold

This kind of organic fertilizer is a little different from compost. Essentially, it’s the leftovers of big piles of leaves that have been left to rot. Eventually the leaves decompose, leaving behind a rich, fluffy organic material that makes a terrific plant food.

Leaf mold, especially from oak leaves, tends to have a very low pH (which means it’s very acidic), so it’s best used on plants that prefer a more acidic than alkaline soil.

Lay It On

There are several methods for applying fertilizer:

• Broadcasting

• Banding

• Side dressing

• Foliar feeding

Each one has its place in the home gardener’s repertoire.

Broadcasting Fertilizer

If you’ve ever used one of those little spreader contraptions to fertilize or lime the lawn, that’s broadcasting. In the vegetable garden, this kind of broadcasting is the uniform spreading of fertilizer over the whole surface of soil. Usually this is done just

before you till so you can then turn the fertilizer into the soil. You can use the same spreader you use on the lawn; just be sure there’s no lime left in it.

Generally, you don’t want to apply commercial fertilizers until you’ve had your soil tested so you know what formula to use.

Garden Guru Says

Most gardeners don’t refer to an overall application of manure or compost as broadcasting, although technically, it probably is.

Strike Up the Band

Applying fertilizer using the banding method is a highly reliable way to deliver nutrients to young plants, but it does require a fair amount of labor. Banding is done at the same time you plant seeds and at transplant time.

The amount of fertilizer you use depends on the results of your soil tests and what crop you plan to grow.

Here’s how to band fertilizer:

At seed planting:

1. Dig two furrows parallel to, on either side of, and 3 to 6 inches from the seed furrow. Make them twice as deep as the seed furrow.

2. Add the fertilizer in the furrows and cover with soil.

Or …

1. Dig a furrow 3 to 6 inches deep.

2. Add the fertilizer and cover with soil.

3. Plant the seed in the furrow.

At transplant time:

1. Make two furrows 6 inches long and 3 inches deep on either side of each transplant. The furrows should be 4 to 6 inches from the transplant.

2. Add the fertilizer and cover with soil.

Or …

1. Dig a circular trench around each plant 3 inches deep and 4 to 6 inches away from the stem.

2. Add the fertilizer and cover with soil.

Or …

1. Dig a hole twice as deep as you need for the transplant.

2. Add the fertilizer and work it into the soil at the bottom of the hole. Fill the hole with soil to the level needed for the transplant.

3. Plant the transplant.

After all the furrows or holes are dug and filled and the seeds or transplants are planted, water thoroughly.

Banding fertilizer allows plants to have easier access to the phosphorus they need for good root development.

“I Like My Dressing on the Side”

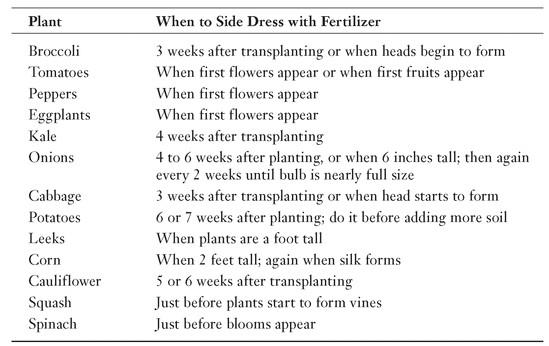

This application method is done when young plants have reached a certain size. It’s done by taking a small amount (1 or 2 tablespoons per plant) of a dry fertilizer and sprinkling on both sides of the row of vegetables or in a circle around individual plants. Allow 6 to 8 inches of space between the fertilizer and the plant. Then gently work the fertilizer into the soil with a cultivating tool and follow with a thorough watering.

Not all vegetables like getting a side dressing of fertilizer. Those that do like it at different times. The following table helps you know when to side dress some of your favorite vegetables.

Garden Guru Says

When a side dressing is not worked into the soil but simply left on top of the soil, it is called a top dressing.

Some perennial plants like asparagus and artichokes benefit from a side dressing of fertilizer, too.

Foliar Feeding Frenzy

If you read foliar and thought it sounded a lot like foliage, you’re right. And you’ve probably also figured out that foliar feeding is a way of applying fertilizer to the leaves of a plant. Right again.

Applied as a spray, foliar feeding is a quick fix for plants and helps them absorb the nutrients they need. Generally, foliar feeding is done when there hasn’t been enough fertilizer added to the soil before planting; when micronutrients, especially iron and zinc, aren’t being released adequately; or if the soil is too cold to allow the plants’ roots from taking up the existing fertilizer in the soil.

A phosphorus foliar spray can also help new transplants get off to a good start in cold soil.

The Least You Need to Know

• Well-rotted manure is an excellent alternative to commercial fertilizers. Never use waste from dogs, cats, or humans as manure.

• Avoid contributing to fertilizer runoff by only using the amounts recommended by the manufacturers.

• Look for Earth-friendly organic fertilizers as an alternative to synthetic options.

• Water thoroughly after applying all fertilizers, except foliar types.

• Apply a foliar fertilizer spray to give plants a quick feeding, especially when the soil is too cold for the plants to take up fertilizer from the soil.