Chapter18

Growing Fruits

In This Chapter

• Tricks for raising strawberries

• Grow-your-own melons

• Reintroducing rhubarb

• A bowl of (ground) cherries

Many gardeners like to grow small fruits along with their vegetables. It’s not hard to understand why. If you’ve ever harvested a basket of strawberries in the afternoon for your strawberry shortcake at dinner, you know the sublime pleasure of growing your own fruit. And what’s a summer picnic without juicy slices of watermelon?

In this chapter, we learn more about growing small fruits, including strawberries, rhubarb, and melons. And in case you haven’t met yet, we introduce you to ground cherries.

Sweet, Sweet Strawberries

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Americans consume 4.85 pounds of strawberries per person per year. California, which is the country’s largest producer of strawberries, grows 1 billion pounds every year. Think about it. Strawberries are huge! I don’t have enough room in my garden to grow my own, so I rely on my CSA and a few pick-your-own farms in my neighborhood because the flavor of fresh-picked strawberries is unequaled. And I like to have enough to put up a dozen or so half pints of strawberry jam.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

To grow strawberries in very cold climates, follow the advice of the experts at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension: plant strawberries on a slight slope to allow cold air to float away from plants rather than settle in with them. The slope has the added advantage of improving drainage.

Strawberries can be grown in every state in the country, but they do best in places where they can have a full 90 days of warm days with full sun, cool nights, and regular watering.

Strawberries prefer well-drained, deeply cultivated sandy loam with a pH of 5.8 to 6.2 and plenty of organic material worked in thoroughly. Strawberries are heavy feeders, so you’ll be doing them a favor by adding a 10-10-10 fertilizer to the bed before planting. For about 250 square feet of strawberries (about enough room for 100 or so plants), you’ll need about 5 pounds of fertilizer. (See Chapter 20 for more information about fertilizers, including organic options.)

Weeds are a real problem for strawberries; they just don’t do well with competition. So if you’ve turned a lawn into a planting bed, wait a year until you plant strawberries, and be diligent about removing weeds during that time. (And if you’re going to allow that extra year, why not bring in a truckload of manure to welcome those strawberry plants?)

There are three basic types of strawberries:

• June or spring bearing

• Everbearing

• Day neutrals

Generally, home gardeners work with everbearing or day neutral varieties, both of which produce over a longer period of time versus the June or spring bearing types.

Plant strawberries as seedlings as soon as you can work the soil. Just barely cover the roots with soil and take care not to cover the crown or it will rot.

You can use one of three different spacing techniques with strawberries:

• Matted row

• Space matted row

• Hill

The matted row is good for June or spring bearing types. With the matted row, runners form 15 to 18 inches of mat “daughter” plants spaced 4 to 6 inches apart. Allow 3 or 4 feet between the rows and 18 to 20 inches between the plants.

The space matted row is good for all types of strawberries. Here, runners are limited to 2 to 4 daughter plants spaced 6 to 12 inches apart. Allow 3 or 4 feet between the rows and 18 to 20 inches between the plants.

Finally, hills are best for everbearing and day neutral plants. Here, all runners are removed. The rows are 2 or 3 feet apart, and plants are spaced 12 to 15 inches apart.

Strawberry plants generally last several years, with the runners supplying new plants. The hill system of planting, however, quickly tires the plant, so you’ll have to replant every couple years.

Strawberries do best in zones 4 through 8, depending on the variety.

Get a Load of Those Melons!

Melons come right after tomatoes on my list of favorite summer garden crops. These sweet, juicy fruits can be a challenge to grow because they need a lot of room, warm temperatures, and plenty of water. But they are also great fun, especially for kids.

Melons are members of the Curcubitacea family and are relatives of cucumbers and squash. They originated in the Middle East, where they remain a very important part of the agricultural scene.

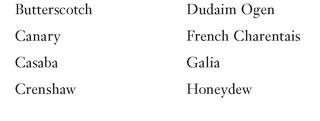

In addition to cantaloupe and watermelon, the two most commonly grown melons in the United States, some gardeners enjoy growing these other melons:

Most melons are vining plants that can take 6 or more square feet of garden space per plant. So to grow them, you need to have lots of room to let them sprawl. That said, plant breeders have been developing more compact bush varieties. Look for these if your space is somewhat limited.

If your garden is really small, you could try growing melons on a sturdy trellis or in a wire cage. But because melons are pretty heavy, you’ll need to support the fruit as it matures.

Garden Guru Says

Here’s a reuse tip that not only helps in the garden, but keeps out at least a little of the 3.9 million tons of textiles that enter the waste stream every year: fashion inexpensive supports for heavy melons with slings from pantyhose legs. Ease the stocking over the fruit, cut off a section, and make slits to form a pair of ties. Then tie the sling to a trellis or stake. The material expands with the growing fruit, keeping it supported above the ground where it might rot. This trick works for squash, too.

Unless you garden in a warm zone, start melon seeds indoors, and transplant the young seedlings on to large hills well after all danger of frost has passed, as they need warm weather to thrive. If you live in a warm zone, you can start your melons from seeds outdoors. If you live in a cooler zone, you can warm up soil temperatures early and keep it warm by using black plastic mulch in your melon patch.

The Summer of Watermelons

These giant, improbable fruits are the essence of summer. They don’t ask for too much besides plenty of space, lots of sun, warm weather, and loads of water.

Watermelons, unlike their close relatives, do best in soil that has not been amended with compost or manure. They actually prefer a poorer soil and will thank you for not fertilizing them during the growing season.

Plant one watermelon on top of each planting hill and allow 6 to 8 feet in every direction.

Watermelons generally take from 75 to 100 days to mature, so be sure to leave them on the vine long enough to ripen. In zones with short summer seasons, leave the melon on the vine until just before the first frost. Harvest by cutting the stem with a sharp knife or garden shears.

Food for Thought

Huge watermelons are just the thing for big family gatherings, community picnics, or summer buffets for a crowd, but for small families, one of the mini varieties make much more sense. Most are round, many are seedless, and a few ave yellow flesh. All are as delicious as their mammoth cousins.

Growing Cantaloupe

The cantaloupes we are most familiar with in the United States are actually muskmelons (Cucumis melo ‘reticulatus’). The “true” cantaloupe (Cucumis melo ‘cantaloupensis’ ) has a much different skin that’s “rough and warty,” according to the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service, as opposed to the smoother, “netted” skin of American ’lopes.

You can plant as many as three cantaloupe seedlings on a large hill. Just give them plenty of organic matter in the soil, and feed them every 2 or 3 weeks with a high-nitrogen liquid fertilizer like a manure tea. To avoid the fruit rotting before it’s ripe, some gardeners put a small piece of plywood under each fruit to keep it off the soil.

Updating Old-Fashioned Rhubarb

Have you ever tasted pie made from fresh rhubarb? It’s one of those old-fashioned treats that stays vivid in your memory.

Rhubarb does seem like an old-fashioned fruit, but many up-to-date gardeners grow it with enthusiasm and success. As with most fruits, growing rhubarb requires some patience because you can’t harvest it until the second or even third year after you plant it.

Rhubarb, which originated in Asia, is grown for its green, red, or pink stalks that are shaped like celery, only longer. These stalks are used to make pies, jams and jellies, stewed desserts, and sometimes punch (that’s really old fashioned!).

Compost Pile

The leaves of the rhubarb plant contain oxalic acid, which is poisonous. Although a few bites of leaf aren’t likely to kill a healthy adult, it can still make you quite sick. And someone in ill health, or small children, might become very sick indeed from ingesting even a small amount. Remove the leaves immediately upon harvesting the rhubarb stalks.

The stalks of the rhubarb plant look like beautiful red celery. Raw stems are tart when they are young and thin, but as they mature they’re remarkably bitter.

©iStockphoto.com/StefanFierros

Rhubarb likes well-drained soil with plenty of organic matter worked in thoroughly. Although it’s not all that fussy about pH, a range of 5.6 to 6.5 is best. Plant crown divisions, which are available from garden centers, nurseries, and online vendors, in the early spring or late fall, placing the crowns about 2½ to 3½ inches below the soil. Allow about 3 or 4 square feet per plant. Rhubarb is a heavy feeder, so plan on a regular fertilization schedule. Apply a high-nitrogen fertilizer a month after the leaves first appear and then about every 3 weeks after that.

To harvest, cut individual stalks a few at a time, over the course of a month or two, usually starting around mid-May.

Rhubarb is grown in zones 5 through 8.

Food for Thought

Rhubarb plants will last for years, but they do best when they’re divided every 3 or 4 years (unless the plants aren’t thriving). To make divisions, use a sharpspade to cut straight down through the crown. Dig up the two halves and, using sharp, clean knife, further divide the crowns, being sure each small piece has one bud, or eye. Plant the divisions as individual new rhubarb plants.

Getting to Know Ground Cherries

My first experience with these marble-size orange- or yellow-colored fruits was when a vendor at New Hope’s farmers’ market offered me a handful to try. After enjoying their taste—a cross between strawberries and pineapple—I bought a pint of this hard-to-find treat and have been a fan ever since.

The Latin name for ground cherries is Physalis pruinosa, but they are also called husk tomatoes (not to be confused with tomatillos) and cape gooseberries.

Ground cherries are grown in much the same way as tomatoes, although some people like to plant them on mounds. You can start them from seed indoors 3 to 6 weeks before the last frost, but they like the soil to be quite warm before they’re set out.

Ground cherries should never be allowed to dry out but must have good drainage. They like a rich, moist soil, so mulching is helpful. As with many plants, it’s best to water them at the root level, rather than from above.

The plants grow like small bushes, up to 3 feet high and equally wide, and they sometimes need staking or caging. You’ll know the ground cherries are ready to be harvested when the fruit, covered in a papery beige husk, drops from the plant. Be sure to get to them before the birds do!

The Least You Need to Know

• Most backyard fruit plants grow best with good drainage.

• Strawberry plants require about 90 days in warm, sunny conditions to produce ripe fruit.

• Mulch your strawberry plants heavily for higher yields, to keep weeds down, and to help retain moisture.

• Melons take a long time to reach maturity, so start them early.

• Rhubarb plants will produce for many years, especially if they are divided every three or four.