Chapter17

Exotic and Unusual Edibles

In This Chapter

• A taste of Asian vegetables

• Planting specialty vegetables

• Growing heirloom vegetables

• A look at some more esoteric vegetables

In some parts of the country, some plants are everyday fare. In other parts of the country, those same plants are considered exotic.

For example, okra is almost ubiquitous in Deep South gardens, but might be rarely seen in Maine or Michigan. Artichokes are common along the central coast of California but an uncommon sight almost everywhere else. Bok choy, mitsuba, and mizuna are staples in gardens tended by Koreans, Chinese, Vietnamese, and others of Asian descent, but are still far from standard in mainstream backyard gardens. And specialty roots like kohlrabi, horseradish, and fennel have devoted followings, but aren’t in everyone’s garden vocabulary.

In this chapter, we broaden our gardening horizons and perhaps help bring a little more diversity to our dinner tables.

Asian Specialties

As the number of Asian Americans increases, so does our awareness of the specialty vegetables many people of that community consider everyday fare. Most grocery stores now carry bok choy and Chinese cabbage.

In the following sections, we look at some of these basics. We also suggest a few more you might want to try.

Get to Know Bok Choy

An essential for stir-fried vegetable dishes, bok choy has become more or less a mainstream vegetable in many markets. Bok choy is a cool-weather green that grows in rich, well-cultivated soil, and bolts when the temperature rises. It’s becoming an important fall and winter farm crop in parts of the Southwest where winters are warm.

Garden Guru Says

Bok choy, whose Latin name is Brassica rapa sp. Chinensia, goes by many names, depending on the heritage of the person who is growing or buying it. You might see baak choi, pai tsa, chongee, pak choy, joi choy, or tak tsai.

Sow bok choy seeds about 1 foot apart in well-prepared beds as soon as the soil can be worked, and keep them well watered. The seeds germinate in a week or so, especially if the soil is nice and warm.

You can begin harvesting individual leaves when they’re a few inches long. Small heads of bok choy can be cut at the soil line when they’re as little as 6 inches high—then it’s baby bok choy, which is really expensive to buy. You can continue to harvest individual leaves or wait to pick nice big heads later in the season.

Mitsuba (a.k.a. Japanese Parsley)

Cryptotaenia japonica, or mitsuba, looks a lot like cilantro but with slightly larger leaves. It is a hardy perennial that grows in zones 4 through 9. In colder places it’s grown as an annual.

Sow seeds in late spring and again in late summer for an abundant harvest. You can make additional sowings every month or so throughout the summer. Mitsuba grows in the shade and prefers rich soil with plenty of organic matter worked into it. Harvest about 50 days from seed planting by cutting individual stems.

Mizuna (a.k.a. Kyoto Greens)

Mizuna is a loose-heading lettuce-type green with curly leaves that look a little like endive but are very dark green. Mizuna tolerates more heat than most lettuces and is grown much the same way.

Prepare the soil so it’s rich and light with lots of organic matter. Sow the seeds on top of the soil (they need light to germinate), and pat them gently into the soil. Keep the seeds well watered using a fine mist.

The seeds germinate quickly, and you might actually begin to harvest tiny, baby greens just a couple weeks after sowing.

Hybrid Senposai

A new Japanese hybrid, Senposai is a cross between cabbage and Komatsune mustard greens. The rounded, fan-shape leaves somewhat resemble collards and have a texture similar to lettuce. You can add the tiny leaves to salads or use the more mature leaves in soups or stir-fries as you might kale or chard.

Sow seeds indoors in regular potting mix or outdoors after all danger of frost has passed. Space seedlings 9 to 12 inches apart. You can begin to harvest small leaves in 30 to 40 days after germination.

Other Asian Favorites

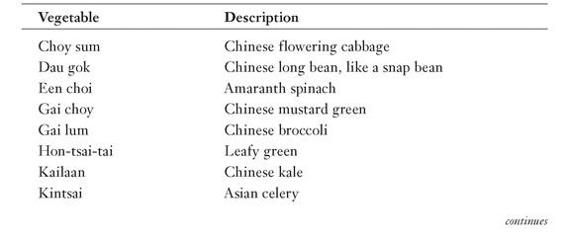

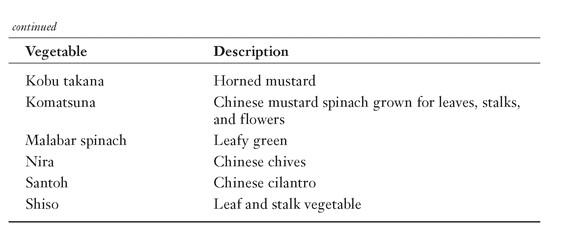

If the preceding sections didn’t give you enough flavor of Asian vegetables, the following table lists some other Asian favorites you might want to check out.

Specialty of the House

The vegetables profiled in the next few sections might be completely unfamiliar to you, or they might be things you grew up with. Most of these are not available everywhere all the time, so they might be special to you.

Growing Oysters in the Garden

Salsify, also known as oyster plant, is an old root vegetable that, according to his garden diaries, was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson, who imported the seeds from Europe. It looks a little like a parsnip, only longer and thinner.

Salsify got its “oyster plant” name because it does actually taste like oysters. Some gourmet food markets occasionally offer salsify for sale, but generally, if you crave this unusual root vegetable, you’ll have to grow it yourself.

Salsify is grown in much the same way as other tap-rooted root vegetables, including parsnips and daikon radishes. They need the soil to be deeply cultivated, well drained, with a pH of 6.0 to 6.5, and rich with organic matter. Salsify takes up to 150 days from seed to harvest and should be planted as early as the soil can be worked. Sow seeds 1 or 3 inches apart and then thin out the weaker seedlings, leaving a space of 3 or 4 inches. You can use the green leaves of the thinnings for salad or cook them like beet greens.

Garden Guru Says

Salsify goes by other names. If you can’t find it or “oyster plant,” try Tragopogon porrifolius or vegetable oyster.

You can also plant salsify as a fall crop in warm zones because it’s very cold tolerant. Some gardeners say it tastes better if the plant experiences a heavy frost. Harvest by pulling up the entire plant.

Tomatillos: Not Green Tomatoes

Nearly 30 years ago when I lived in Mexico, I was introduced to the tomatillo (Physalis philadelphica) or husk tomato, an essential for salsa and enchiladas verdes. Today, you can find tomatillos in many grocery stores in areas with a large Latino population.

A tomatillo is not a tomato, or even a close relative, but a completely different plant. The tomatillo does look a lot like a tiny green tomato, but it is firmer, has a thicker skin, and is covered in a husk that has the thickness and texture of tracing paper.

Start tomatillo from seeds using the same methods you would for tomatoes. Tomatillos are warm-weather plants, so wait until all danger of frost has passed. Allow about 100 days from seed to harvest, although some varieties require less growing time.

Tomatillos are large plants that have a tendency to sprawl all over the place. Using tomato cages or wire and stake supports might help keep them under control. Harvest tomatillos when the outer husk splits open.

Say Hello to Broccoli Raab

Yet another Brassica, B. rapa or sometimes known as B. ruvo, broccoli raab is a cool-weather plant popular with those who like Italian cuisine. The stems, leaves, and tiny unopened flower buds are all edible.

Broccoli raab, which is also called rapini, likes rich, well-drained soil with lots of organic matter mixed in and a pH of 6.5 to 8.0. It can be directly seeded in beds or grown from transplants placed about 6 to 12 inches apart.

This fast-growing plant bolts if exposed to hot weather, so get it going in early spring for a late-spring harvest or in late summer for a fall harvest. In places like California and Arizona, broccoli raab is a winter crop.

Okra Is A-Okay

Okra, or Abelmoschus esculentus or Hibiscus esculentus, is a relative of the ornamental hibiscus, and interestingly enough, cotton. With its big white flowers, okra can be a very pretty plant. Try using it in an ornamental bed as well as the vegetable patch.

Okra is pretty easy to grow, requiring a neutral soil, lots of sun, and warm temperatures. You can start seeds outdoors about 2 weeks after the last frost or start them indoors about 6 to 8 weeks before that date. To give the seeds a head start, place them between a couple wet paper towels overnight before planting. Sow the seeds about ½ inch deep in medium-size hills placed about 2 feet apart. Okra gets pretty tall, sometimes up to about 5 feet.

Compost Pile

The leaves and stems of okra plants contain tiny hairs that can irritate your skin, so wear gloves and long sleeves when you’re harvesting or working around them.

While most vegetable plants like well-drained soil, okra is particularly picky about it. It’s better to underwater than to overwater this plant.

The edible part of okra is the immature seed pod. Harvest when the pods are no more than 6 inches long, but try to get them when they’re even smaller—around 2 or 3 inches.

Growing Heirlooms

Heirloom plants are those open-pollinated varieties introduced more than 50 years ago. More specifically, heirloom varieties are the resurrected varieties of plants that were grown by farmers and gardeners before the mass production and mass distribution of seed, and before farming became big business.

Growing heirlooms is another step you can take to make your garden more Earth-friendly. Using heirlooms preserves genetic traits and a larger gene pool for future generations. A reduced gene pool can lead to increased susceptibility to diseases and pests. Also, unlike seeds of hybrid plants, heirloom seeds reliably produce plants with the same traits as their parents.

Here, we look at some specific heirlooms that are particularly interesting and fun to grow, including tomatoes, corn, squash, and peppers.

Terrific Tomatoes

Among the most fascinating heirloom plants are tomatoes, many of them throwbacks to the turn of the century. One of the joys of these old-fashioned plants is that they retain the true tomato flavor that’s often lacking in the new varieties that have been bred for disease resistance, uniform size, ripening qualities, and long shelf life, often at the expense of flavor.

Heirloom tomatoes are grown using the same techniques as modern tomatoes. Some might need careful staking, others are not particularly prolific, and a few might be a bit more susceptible to diseases. But if true tomato flavor is one of your favorite things, growing heirloom varieties will be worth the effort.

Check the following table for a few other varieties to look for.

Food for Thought

In his 1942 Victory Garden in Long Beach, California, Prof. Price grew the relatively new Rutgers tomato that had been introduced in 1934. That tomato became the standard for decades until plant scientists developed newer varieties to eet the demands of the canned food industry.

Crazy About Corn

Corn is another one of those vegetables that has been extensively hybridized to the point that some purists find ridiculous. Today, mass-produced corn has been bred to stay sweet days after picking, which is a boon for those who can’t grow their own and don’t live near enough to a farm to buy it fresh. But that sweet taste, some would argue, is a far cry from the true corn taste that’s so dear to our American heritage. Heirloom varieties, including some hybrids developed around the turn of the century and even earlier, allow gardeners to step back in time.

Heirloom corn is grown the same way new varieties are. The big difference is that these old varieties tend to lose their flavor soon after picking, so get that pot boiling before you head to the cornfield.

Super Squash

Old-fashioned squash varieties are, for the most part, a pretty funny-looking bunch. Many of them are winter types, including pumpkins, and a lot of them have strange shapes and lots of lumps and warts.

One particularly interesting one is Long Island Cheese squash. It’s shaped sort of like a wheel of cheese, is tan on the outside like a butternut squash, and is bright orange inside. And each fruit can weigh as much as 20 pounds! Another old beauty is the Blue Hubbard. The Burpee heirloom catalog says it might have originated somewhere in the Caribbean and was brought to Massachusetts in 1798.

Other wonderful old varieties include the Native American scallop squash, Sibley, which was popular in the 1840s, Amish pie squash, the Georgia candy roaster, and Turk’s turban, a favorite from France, pre-1820. Heirloom squash are grown using the same planting methods as modern varieties of squash.

Perennials—They Keeping Coming Back

Most vegetables are grown as annual plants. We harvest them when they fruit, and generally the plant dies and we replant the next year. A few vegetables are biennials, but we still harvest them in the first year and ignore their 2-year life cycle.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Biennials are plants that develop roots, leaves, and stems in their first year but do not flower and produce fruit or seed until the second season.

A few vegetables are true perennials and go through the fruit-production cycle year in and year out. Artichokes and asparagus are the best-known and most-often grown perennial vegetables. Another plant, cardoons, are popular in Europe but still don’t have a large following in this country.

Globe Artichokes

Globe artichokes are huge, beautiful plants (Latin name Cynara scolymus) that produce flower buds treasured by gourmets and gourmands all over the world. And although they’re considered a delicacy, artichokes aren’t all that difficult to grow, as long as you provide them with a hospitable environment.

For the most part, artichokes prefer relatively cool weather. According to the Reimer Seed Company, they need 250 hours of below 50 degrees Fahrenheit to set their buds. That’s only about 10½ days. If you grow artichokes from seed, start them indoors about 6 to 8 weeks before the set-out date that’s after the last predicted frost. In warmer climates, plant artichokes in the late fall for a spring harvest. But be advised: artichokes really don’t like very hot weather. And they do require regular irrigation.

Globe artichokes are reliably hardy in zones 8 to 10. In zones 6 and 7, they might survive milder winters with a good layer of mulch.

Place artichoke plants about 2 or 3 feet

apart. To harvest, pick the immature flower buds along with a

couple inches of stem using a sharp knife. Harvest baby artichokes

before they develop the prickly choke that must be removed from the

mature flower bud before you eat. The baby form is ready to harvest

when it’s about 3 inches across, or about the size of the mature

bud.

the size of the mature

bud.

Artichoke plants die back in colder zones but grow year round in places like Castroville, California—the artichoke capital of the world. California artichokes produce from March through May and again in October through December. Some artichoke growers cut plants back after the first harvest and allow them to send out new growth for the second harvest.

From the Asparagus Patch

Asparagus is another highly prized gourmet vegetable that’s an essential for Easter dinner in our family. This is a relatively demanding plant to grow, only in that you

have to wait a year after planting to get the first sparse harvest. Asparagus pays you back for your efforts, however, because the plants continue to produce for 10 or even 15 years.

Home gardeners rarely grow asparagus from seed. Instead look for 1-year-old crowns.

Reserve an area in your garden for your asparagus patch, keeping in mind that each asparagus crown will produce about ½ pound asparagus each year and that crowns should be planted about 18 inches apart in rows about 5 feet apart. You can do the math to figure how many crowns and how much space you’ll need.

Garden Guru Says

When you buy asparagus crowns, insist on male plants. These are hybrids that have developed in recent years and don’t produce seeds the way the female plants do. Plants that grow from these seeds could become a weed problem in your asparagus patch.

Dig furrows about 5 inches deep and add a dose of triple superphosphate to the soil at the bottom of the furrow, working it into the soil. Asparagus likes soil with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0. Then put the crowns in the furrow, cover lightly with soil, and water well.

Although the asparagus produces a few spears its first year, leave them alone and let them die back. The second year, you’ll have a small harvest, with a full harvest in the third year and after.

Asparagus grows in zones 4 through 10.

Ever Heard of Cardoons?

These Mediterranean favorites are a close relative of artichokes. And although cardoons still haven’t made much of an inroad in the United States, adventuresome gardeners eager to try new things are beginning to give cardoons a small presence here, particularly in the Pacific Northwest where the climate conditions seem to be especially hospitable.

Cardoons are very large perennial plants with massive leaves that can be as long as 5 feet. Young new leaves and the immature flower stalks are the edible part of the plant.

Cardoons do not tolerate frost and prefer moist, cool conditions. They like rich, well-drained soil that’s deeply cultivated to ensure good root formation. They also require regular irrigation.

Plant seeds outdoors after all danger of frost, spacing them about 1½ to 2 feet apart. Or purchase stem suckers, which are commercially available rooted offshoots, and plant them with the same spacing.

Cardoons grow in zones 7a to 9b.

Garden Guru Says

According to a University of Oregon Extension Center publication, cardoons need to be blanched (blanche is French for “white”) starting about 1 month before harvesting. This is usually done by tying up the leaves at the top and wrapping them with burlap or paper. The leaf stalks are the parts that are blanched.

Exotic Roots

Some foods that we think of as root vegetables are actually the thickened stems of the plant rather than actual roots. Kohlrabi and fennel are two such exotic fat stem plants that we’ll look at in this section. We’ll also cover Jerusalem artichokes and horseradish.

Cabbage + Turnip = Kohlrabi

Kohlrabi is another member of the Brassicas (Brassica oleracea var. caulo-rapa) and one of the easiest of that family to grow. Kohlrabi, which means “cabbage-turnip” in German, is considered a root vegetable, although the round, rootlike part we eat is actually a swollen stem that forms above the ground.

As with many of the Brassicas, kohlrabi likes cool weather. You can sow seeds directly 1 to 1½ inches deep in the garden in early spring and in the late summer for a fall crop. In warm zones, plant in late fall for a winter crop.

Provide them with a rich neutral soil that’s been amended with plenty of organic matter. Allow 4 to 8 inches between plants. You can also start seeds indoors allowing 5 or 6 weeks for seedlings to develop before set-out time.

It’s very important to keep weeds out of the rows where you grow kohlrabi, or you risk misshapen, stunted vegetables. Take care when weeding because the kohlrabi has shallow roots. Mulch helps considerably; just keep it away from the round stems.

Harvest when the stems are about 2 or 3 inches across by cutting through the roots just below the stem.

Food for Thought

Kohlrabi plants that have grown quickly are said to have the best flavor. To row at a substantial rate, grow at a substantial rate, they require regular watering and every-other-week applications of a quick-release fertilizer.

Aw, Horseradish!

Did you ever wonder where that white, grainy pickled stuff that you add to ketchup to make cocktail sauce comes from? It’s horseradish, a wonderful root vegetable that’s pretty easy to grow.

Horseradish grows in cool to cold weather and is usually planted in the early spring or late fall. Plant roots in furrows 1 foot deep, spacing the roots about 1 foot apart. Be sure the soil is well drained, and avoid overwatering.

Harvest horseradish in the late fall, usually after a hard frost. This plant is a biennial that’s generally grown as an annual. To collect seeds, leave one or two plants in the garden and allow them to die back. They’ll grow back the following spring. Allow them to mature, and they’ll produce seeds. The root will probably be too tough and woody for consumption.

Fennel (the Vegetable, Not the Herb)

It’s important to differentiate between fennel, the herb, and fennel, the garden vegetable. Here we’re talking about the vegetable, Foeniculum vulgare var. dulce. It’s a particularly beautiful plant and can be used as a decorative foliage plant in an ornamental garden—with the added bonus that you can eat it later.

Fennel is generally grown from seed and planted outdoors after the last predicted frost. Space fennel about one every foot or so.

Harvest fennel about 70 to 80 days after the seeds have been sown, usually when the bulb, which is actually thickened stems that grow in an overlapping pattern, is about 3 or 4 inches across. You can blanch the bulb, which sits up in the soil above a tap-root, by mounding soil up around it for a couple weeks before harvest.

Bulb fennel, which is sometimes called finocchio or Florence fennel, prefers a pH of 5.0 to 6.8, frequent watering, and cool weather. Keep the soil moist but not soggy to avoid having the bulb split, which will ruin the flavor.

Celeriac (a.k.a. Celery Root)

Celeriac, one of my new favorites since I was introduced to it by my CSA, is also called celery root. It’s far better known in Europe, where it’s served au gratin or julienned, than it is in the United States.

If you’d like to try growing this esoteric veggie, you’ll most likely have to start it from seed, as it’s not generally available as a seedling.

Celery root takes 100 to 120 days from seed to harvest, so start the seeds early. Grow it as you would a turnip.

Artichokes from Jerusalem

Jerusalem artichoke is a giant plant, Latin name Helianthus tuberosus (which tells you they are related to sunflowers), that grows up to 8 feet tall. The fleshy tubers are another example of a swollen, underground stem. They’re eaten like potatoes, harvested in the fall, and can remain in the ground until just before or just after the first frost.

Grow these plants starting with pieces of tuber in a rich, sandy loam, planting them in early spring. Allow at least 2 feet between each plant.

They don’t like hot weather.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

The Jerusalem artichoke stores carbohydrate as insulin, instead of starch. Insulin is metabolized as fructose instead of glucose when eaten—this quirk makes Jerusalem artichoke a starch substitute for diabetics.

Baby Vegetables

Some of what we call baby vegetables are just that: they are the plant’s fruit picked when it’s still in its early stage of development—far enough along to look and taste like that vegetable but with a milder flavor and tender texture. Other so-called baby vegetables are actually varieties that have been bred to be tiny versions of the original.

Harvesting baby vegetables is done using the same techniques as for mature vegetables (see Chapter 24); it’s just done earlier. (You’ll also find some hints about when to harvest baby vegetables in Chapter 24.)

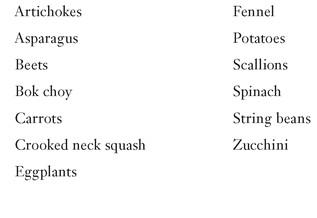

Here are some vegetables that can be harvested when very young and tender:

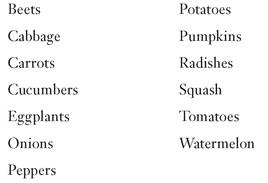

Vegetable plants with varieties that are bred specifically for their mini size include the following:

The Least You Need to Know

• Don’t be afraid to try new and unusual plants. They’re often as easy to grow as the basics.

• Grow old-fashioned heirloom vegetables for authentic flavors and to contribute to a healthy gene pool for plants.

• Harvest some veggies early as babies, or try some specialized dwarf or mini varieties of your favorite vegetables.