Chapter 8

The Science of Soil

In This Chapter

• The real dirt on soil

• Determining your soil’s pH

• How does your soil drain?

• Testing … testing … your soil

• What’s in—and what’s not in—compost

For farmers, gardeners, and plant scientists, soil is a really big deal. So much so that some people get Ph.D.s in soil science. There are even entire departments at state universities devoted to the subject.

In this chapter, we look at the many properties and variables of soil, find out what pH is and why it’s so important to gardeners (and plants!), and learn about the various nutrients that enhance the quality of soil. This is also where you find out everything you’ve ever wanted to know about compost.

Dirt Is a Dirty Word

If you want to call yourself a gardener, you must swear never again to use the word dirt when you mean soil. Just remove dirt from your vocabulary. To provide plants with an environment in which they can thrive, gardeners need to know at least a little bit about the chemical and physical makeup of soil.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Soil provides the mechanical support, water, and nutrients plants need to grow.

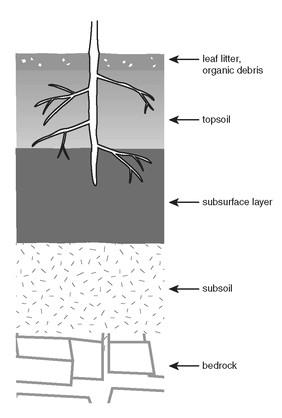

Soil is made up of several layers of different materials. The top layer consists of leaves and organic debris. Just below that is what we think of as topsoil. It’s also called surface soil, and it usually includes a fair amount of organic matter. Next comes the subsurface layer with decomposed organic matter and mineral compounds. Below that is the subsoil that can be a combination of enriched clay, minerals, organic compounds, and loose rocks. All these layers lie on top of bedrock. Different parts of the country have different thicknesses and even concentrations of materials at each layer, but the basic set of layers is more or less the same.

Typical soil contains several layers of materials, from the surface organic debris all the way down to bedrock.

Soil is also made up of mineral materials such as particles of gravel, sand, clay, silt, and organic matter, including broken-down plant and animal remains. Air and water are also soil ingredients.

Most soil components—such as clay particles, sand, and organic matter—are important for the soil’s physical structure. They determine how well water and nutrients become available to plants. Soil also contains tiny amounts of minerals that actually are the nutrients. (We learn more about these nutrients and how they work in Chapter 20.)

The Feel of the Soil

Soil texture is an important factor because it affects how water passes through soil and how quickly the soil warms up and retains heat. Soil texture ranges from the finest silt to the densest clay. In between is loam, a rich soil containing clay, sand, and organic matter. Other soil types include silty clay loam, sandy loam, clay loam, sand, loamy sand, and sandy clay loam. Most vegetable plants like to grow in loamy soils.

You can improve the texture of your soil by adding peat moss, leaf mold, decomposed grass clippings, manure, and compost. Be cautious with peat moss, though, because it can become compacted and act like a moisture barrier, preventing moisture from descending to the plants’ root zones.

Tip-Top Soil

Surface soil, or topsoil, is the best for growing plants. It’s usually made up of 50 percent solid materials that are a combination of minerals and organic matter. The other 50 percent is open or pore space that is filled with either air or water.

Ideally, the pore space is half air and half water. After a rain or a period of irrigation, there will be more water than air. When it’s been dry for any length of time, there’s more air than water.

Organic Matter

Organic matter in soil refers to the remains of plant material. It can take the form of sawdust, wood chips, pine needles, kitchen scraps, dried leaves, straw, grass clippings, and manure. Over time and given the right conditions, organic matter decomposes.

The process of decomposition converts large chunks of organic material into much smaller particles, some even too small to see under a microscope. These particles act like miniscule sponges and soak up water. Then they loosely attach themselves to the minerals and nutrients in the soil. The result is a soil that’s much more friable, or crumbly, a little like rich chocolate cake (that’s the optimum soil texture), more moist, and more fertile.

In healthy soil, worms, insects, bacteria, and other microorganisms eat the organic matter and produce humus and soil nutrients.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Humus is the remaining part of organic matter in the soil after it’s been completely decomposed. Gardeners love humus because their plants love humus. It’s got the color and texture of chocolate cake, is easy to work with, and smells clean and woodsy.

Soil Structure

People who really know their soil usually classify soil structure as either weak or strong, with varying degrees of strength or weakness. This is a description of the shape of soil particles and how they group together. It’s important to understand soil structure because it determines how air and water move through the soil and, therefore, what, if anything you need to do to amend it for your plants.

Soil particles cluster together in little groups called aggregates. The shape of these aggregates determines the structure of the soil. The aggregates range from microscopic grains of sand to what are called “massive” chunks. Some look like tiny pebbles; others look like slivers of mica. Some are porous; others are solid.

Granular soils, which have a texture like miniscule pebbles, allow water and air to pass through easily. This kind of soil has a strong structure. A weak soil has massive kinds of aggregates, making it more difficult for water and air to pass through and for roots to take hold.

You can improve the structure of the soil in your garden by adding things like course sand, vermiculate, perlite, peat moss, compost, manure, leaf mold, sawdust, seaweed, and straw. Be cautious with peat moss, though, as it can easily become compacted and prevent water from penetrating.

The pH Story

When we talk about pH, we’re referring to how acidic or alkaline the soil is. Sometimes this is expressed as how “sweet” (alkaline) or “sour” (acid) the soil is. It’s a logarithmic scale (which is way over my head—my high school math only went as far as a poor showing in algebra), but put simply, it means that a pH level of 6.5 is 10 times more alkaline than a reading of 5.5.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

The pH of soil is actually a measure of the hydrogen ion activity in the soil. It’s measured on a scale of 0 to 14, with 0 being the most acid and 14 the most alkaline. Neutral soil, which is ideal for many plants, has a pH of 7. The more hydrogen present, the more acidic, so a pH of 5.5 has 10 times the concentration of hydrogen ions as a pH of 6.5.

Why is pH so important? If the pH of the soil in your garden is out of whack with the requirements of the plants you’re trying to grow, the plants will struggle to absorb the nutrients they need. For example, most vegetables like to grow in soil with a pH of about 6.5, which is just slightly acidic. If your soil measures 5.5, your tomatoes and peppers will grow slowly, won’t produce as much fruit, and will be more prone to disease. But with 5.5, your corn, beans, kale, and garlic will manage just fine.

Soil That’s Too Acidic

If your soil proves to be too acidic for the plants you plan to grow, you can raise the pH by adding ground limestone. Because relatively little lime is needed to raise the pH to the desired levels, you might want to consult with your local county extension or Farm Bureau office to help you determine the proper amounts for the soil in your area.

In regions like the Northwest and the Northeast, which tend to have acidic soils, an application of lime every 4 or 5 years using a formula of about 4 pounds for every 100 square feet of garden is usually enough for most vegetable gardens. It might take several months for the lime to affect the pH level throughout the beds. The best time to apply lime is at the end of the growing season so it has plenty of time to work.

If organic is your preference, look for organic products like aragonite or dolomitic limestone.

Soil That’s Too Alkaline

If the pH is too high or alkaline, you’ll want to add sulfur, gypsum, or aluminum sulfate. Aluminum sulfate is water-soluble so it will do the trick quite quickly. The other products take a bit more time. A good formula to follow is about 3 pounds sulfur or 5 pounds aluminum sulfate for every 100 square feet of garden.

Garden Guru Says

Used coffee grounds are an inexpensive and environmentally friendly way to add some acidity to a too-alkaline soil. Many coffee shops give away their coffee grounds for the asking. It takes a lot to make a big change in your soil, but if it only needs a little fix, coffee grounds might do the trick on the cheap. If you’re striving for an organic garden, choose organic coffee when you make your purchases.

The Drain Game

The way water passes through soil is called drainage. Good drainage qualities help maintain a deep root zone, eliminate frost heave, bring warmth to soils earlier in the spring, improve soil aeration, and lower disease problems.

Soil with serious drainage issues is easy to spot. It’s wet and squishy, puddles form easily in depressions and low spots when it rains, and the water stays there for a while. Moss growing on the soil is another pretty good indication that soil drainage is poor.

The more organic matter the soil contains, the better the soil is able to retain water. So if you have drainage problems, consider adding organic material to the soil—however, if your drainage problems are really serious, this won’t be enough. You might have to consider cutting swails (ditches to divert water), installing drains, or bringing in a dump truck load of additional soil.

Testing Your Soil

Soil tests help gardeners determine the pH of the soil and the level of available nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. You’ll also receive other information on the texture of the soil, the lime and salt content, and sometimes levels of toxic materials. This information helps you understand what adjustments you need to bring the soil to the fertility, texture, and pH you need to grow specific crops.

Unless you’re growing particularly demanding crops or your land is flooded, you’ll only need to test the soil every 3 or 4 years. It’s best to test in the fall so you can add amendments and allow them to “percolate” through the soil over the winter.

Compost Pile

If your garden is near a heavily traveled road or in the vicinity of an older home that might have had lead-based paint scraped off and improperly discarded, or if there was any kind of industrial activity near where your garden is now, the soil might be contaminated with lead. You don’t want to grow edibles in lead-contaminated soil. Be sure to have it tested.

Follow the directions on the soil test kit. Usually it will suggest 8 to 10 samples from various parts of the garden; if you have a tiny patch, 5 or 6 samples will do. However, if your gardens consists of a number of remote areas—the asparagus patch here, veggies over there, and ½ acre in corn—you’ll need to perform several different tests. Most county extension offices sell soil test kits, as do some garden centers and garden supply stores.

DIY Compost

Compost is the decomposed plant material you collect from the kitchen, yard, garden, and barnyard for reuse as a soil enhancer. Just about any material that started out as part of a plant—including the manure of plant-eating animals—can be composted.

Compost piles need air circulation, moisture, and heat to do their magic, so place your pile accordingly. Avoid putting the pile in a spot that gets full sun all day unless you’re prepared to water it regularly. A part-shade location is ideal.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Compost is plant material that microorganisms have decomposed. Compost microorganisms are those bacteria and fungi that can digest plant material. They occur naturally in soils.

Take the following steps to create a compost pile for your garden:

1. Establish a location for the pile. It should be close to the garden but also convenient to your kitchen.

2. Dig a pit about 4×4 or 4×5 feet and about 1 or 2 feet deep. (This step is optional; but having the pile start out in a pit helps keep in moisture.) Don’t dig a pit if drainage in the area is poor.

3. Add an 8- to 10-inch layer of organic material like kitchen scraps, leaves, grass clippings, or seed-free weeds.

4. Cover the first layer with a thin layer of soil.

5. Water thoroughly, but not to the point of making it soggy.

6. Add more layers of organic material, alternating with thin layers of soil and watering between layers, until the pile is about 4 or 5 feet high.

7. Let it sit for a month or two.

8. Keep the soil moist. If it’s very hot or if there’s no rain, water the pile occasionally, but be sure it never becomes soggy.

9. Cover the pile with a tarp if you get heavy rains for more than a day or two in a row.

10. After 2 months, and then once a month for 3 to 5 months, turn over the pile with a pitchfork or a special “compost screw.”

11. With each turn, check to see that the pile is “cooking.” It should feel warm to the touch.

12. When the material in the pile looks like soil, it’s ready to use in the garden.

Garden Guru Says

Microorganisms need to eat to multiply, but it can take them a long time to digest intact plant material. Give these bugs an energy boost with a big dose of sugar simply by emptying the dregs of soft-drink or beer bottles onto the compost pile after your next backyard picnic.

It’s always a good idea to have a relatively even mix of green and brown materials, like grass clippings and dried leaves, for example, for good-quality and rapid compost. To accommodate all the organic material you might accumulate, you might want to have more than one pile going at a time. You also could consider a commercial compost bin or tumbler that works faster than a traditional pile.

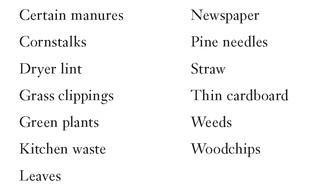

Good composting material includes the following:

Never, ever add grease, meat or fish scraps, dairy products, or bones to your compost heap. These attract vermin, and even worse, the bacteria that break down animal products can cause disease. Only use manure from horses, cows, sheep, goats, rabbits, and chickens. Cat and dog poop is a big no-no because these pets are meat eaters and because the excrement can contain harmful parasites and bacteria. And to prevent the spread of disease or invasive plants, avoid diseased plants and weeds with seeds.

Kitchen scraps make great additions to the compost pile. Keeping a container by the kitchen sink to collect the scraps means fewer trips to the pile outside; the more convenient it is to do, the more you’ll do it.

©iStockphoto.com/Phill Danze

The Least You Need to Know

• The better your soil texture, structure, and pH, the better your plants will be.

• Organic matter makes a good all-purpose soil amendment.

• Adequate drainage is a must for vegetable-growing soil.

• Adjust and amend your soil based on the results of a soil test.

• Organic compost makes a rich amendment to your soil, and it’s pretty easy to create your own compost pile.