Chapter 23

Troubleshooting

In This Chapter

• A look at some diseases that could affect your garden

• Diagnosing fungus on your plants

• Addressing germination and seedling problems

• What leaves can tell you

A lot can go wrong in your edible garden. I don’t want to sound like an alarmist, but even the most seasoned gardeners have had disappointing seasons or even disasters. It goes with the territory.

But to put your plant problems into perspective, it’s important to keep in mind that thousands of plant pathologists, agricultural experts, and farm bureau agents have made plant pathology and the detection of diseases and problems their life’s work. For our purposes here, there’s only so much that can be covered in one chapter. The next few pages are designed to be an overview and a starting point for spotting and diagnosing problems in your garden.

In this chapter, we look at some of the major plant diseases, teach you to identify them, and help you handle them. We also look at a few of the more common symptoms of a distressed plant and some of the possible causes of the problems.

When Your Plants Are Sick

Most plant diseases are viral, bacterial, or fungal (not unlike human diseases). A few are related to nematodes. Then there are some abiotic problems that can occur because of nutrient deficiencies, too much or too little sun, or too much or not enough water.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Abiotic means that the problem is of nonliving or nonbiological origin.

Not every garden plant gets every disease. Some plants seem to get more than their fair share, whereas others are rarely bothered. The following table gives you a quick glance at some of the problems facing a few of your favorite garden plants.

As you can see, the lists of diseases are pretty long. Some diseases are peculiar to a specific plant, whereas others attack a long list of victims. Don’t be totally put off by this, though. Your garden isn’t likely to be invaded by every disease listed here. But the more you grow, the more likely your chances of learning firsthand about these things. The following sections might help you get to the bottom of what’s troubling your plants.

Garden Guru Says

If you’re having trouble identifying what’s wrong with an ailing plant, talk to an expert. But don’t expect even the most experienced plant professional to make a diagnosis without seeing the problem firsthand. Put the evidence (leaf, stem, fruit, insect, whatever) into an airtight plastic bag for your own little show and tell. County agents and master gardeners are sometimes available to help. And some garden centers and nurseries have their own garden gurus on staff.

Dealing With Viral Diseases

As they can with humans, viruses cause mayhem, turning healthy plants into diseased ones in a matter of days, if not hours. There are hundreds of viruses that attack plants. Some of the more common ones include the following:

Some symptoms of viral infection include curled or twisted leaves, mottled or mosaic patterns on leaves, brown or yellow spots on leaves, stunted growth, and small flowers that might be brown or otherwise “off.”

Many plant viruses are spread by insects; aphids, leafhoppers, mites, and whiteflies are the worst offenders. Infected tools and equipment, infected mulch, and even a person’s hands or clothing can also spread plant viruses.

Compost Pile

The tobacco mosaic, a virus that’s deadly for tomatoes, can be spread by smokers. The tobacco in cigarettes can actually carry the virus and the smoker can become the vector (carrier) of the disease. As if you didn’t need another reason to give up smoking!

Unfortunately, viral infections in plants are not treatable by methods available to home gardeners. The best thing to do if you suspect that a plant has a viral disease is to remove it immediately and dispose of it. Keeping weeds and insects under control helps, too.

Never put diseased plant material on the compost pile. Dispose of it by bagging it and putting it in the trash, incinerating it (if that’s allowed in your area), or burying it far from the garden. The quicker you are to react to problems, the less you’ll have to depend on less-than-earth-friendly practices.

When Bacterial Diseases Attack

There are lots of bacterial diseases, but three are of particular concern to vegetable gardeners:

• Bacterial wilt

• Bacterial canker

• Bacterial spot

In the following sections, we cover each of these diseases in detail so you can help keep them out of your garden.

Bacterial Wilt

Anyone who has ever grown cucumbers, zucchini, or pumpkins has probably had experience with this major bacterial plant disease. Bacterial wilt, which is also called vascular wilt, causes buildup of the bacteria within the vascular (water-carrying) system of plants. When the waterways become completely clogged, they can no longer carry water throughout the plant, and it wilts and dies. The disease is systemic, meaning it’s carried throughout the plant, rather than localized, or limited to one part of the plant.

Bacterial wilt primarily attacks members of the cucurbit family, especially cucumbers, squash, pumpkins, cantaloupes, and muskmelons. It tends to leave watermelon alone.

Bacterial wilt is spread by cucumber beetles that have the bacteria living in their bodies. When they come up out of the ground in the spring, they start chomping on a healthy plant, making an opening or wound for the disease to enter. The bacteria is in the insects’ waste and eventually finds its way into the wound. The plant can be dead in a matter of weeks.

When you first see your cucumbers or zucchini wilting, you’ll probably suspect a water shortage. After watering, the plant might perk up a bit, but if it has bacterial wilt, it’ll probably be wilted again the next day.

Some other symptoms include retarded growth and excessive blooms and branching. You might also see that the veins of pumpkins and squash plants turn yellow. This, however, doesn’t happen to cucumbers with bacterial wilt.

One way to help you determine whether your squash or cucumbers have bacterial wilt is to cut a piece of stem from an affected plant. Slowly squeeze the stem and see what comes out. If it’s a white, slimy substance that pulls into a string, it’s most likely bacterial wilt.

Garden Guru Says

Squash borer produces similar symptoms to bacterial wilt. But with the insect infestation, you might actually find one of the caterpillars inside the plant, or you might find tunnels through the stems.

The best way to deal with bacterial wilt is to not have it in the first place. Keeping the cucumber beetle population down is key. But the chemicals that kill them also do a number on bees, and, of course, bees are essential for pollination. Removing infected plants, hand-picking insects, and rotating crops are good natural approaches. If the problem persists after several seasons, consider growing something else instead. Or call your county extension office to ask for some advice on using organic chemical controls that won’t endanger bees.

Bacterial Canker

This nasty-sounding disorder is primarily a disease of stone fruit (which we’re not interested in here) and tomatoes. It starts out locally with dark spots on the leaves or stems that look wet. The disease can also first appear with an overall wilting. Sometimes the stems split up and down, and you might see some dark brown sores (these are the cankers) with necrotic tissue (that’s dead plant tissue). The wilting and splitting is evidence that the disease has entered the plant’s vascular system and is, therefore, systemic.

Bacterial canker is caused by a bacteria that lingers in dead or dying tomato plants, or in host plants like eggplants, peppers, and other members of the Solanaceae family (the nightshade family). The disease is easily spread by splashing water, by small wounds made during transplanting (just a broken leaf is enough), or when the gardener prunes or removes stems while caging or staking.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

A host plant is one that is susceptible to a certain pathogen (virus, bacteria, and so on). An alternative host is one in which a pathogen has taken up residence at some point in its life cycle. The alternative host might or might not be susceptible to the pathogen.

To keep the threat of bacterial canker to a minimum, buy certified disease-free seeds and seedlings whenever possible, disinfect pruners and snips between each cut, wash your hands before handling tomatoes, stay out of the garden when it’s wet, and rotate your crops.

Bacterial Spot

This disease attacks tomatoes and peppers and affects every part of the plant except the roots, especially during periods of high humidity or rainy, wet conditions. Look for raised yellowish lesions (spots) on green tomatoes and on both ripe and immature peppers. The lesions turn brown or black and start to look like scabs. The leaves will develop spots, too, and often drop off. The plant will look absolutely awful, and you won’t want to eat any of the fruit, even if some of it does ripen.

Garden Guru Says

Some gardeners use a copper-based fungicide to treat bacterial spot. The fungicide won’t cure the plant, but sometimes it does keep the bacteria from spreading to the rest of your tomatoes and peppers. Although use of copper is approved for organic produce in the United States, it has been disallowed in Europe.

Bacterial spot spreads pretty much the same way as bacterial canker, and is just as, or more, difficult to treat. You’ll probably wind up just pulling the diseased plants out and discarding them.

The best way to deal with this disease is to prevent it in the first place. Use certified seed, stay out of the wet garden, follow strict garden hygiene, and rotate crops.

There’s a Fungus Among Us

Fungal diseases are another headache for gardeners. They’re insidious, difficult to control, and frequently lethal. These are some of the most common:

• Anthracnose

• Various rusts

• Fusarium wilt

• Downy and powdery mildew

Anthracnose

Anthracnose is a pretty ugly plant disease with various forms that attack a number of vegetables, including tomatoes, beans, cucumbers, peppers, melons, squash, and pumpkins. It’s caused by a fungus that lives in the soil over the winter and is spread by insects, rain, wind, watering, and by infected seeds or seedlings.

The symptoms start with large, round, soft spots on the fruits that might become black or brown and develop quickly into rot. The leaves and stems might develop lesions or spots.

You might find some relief if you spray with an antifungal spray. Other ways to deal with anthracnose include the following:

• Use pretreated seeds.

• Select resistant varieties.

• Practice good garden hygiene.

• Rotate annual crops every year.

• Avoid walking in the garden just after a rain or an overhead watering.

• Keep weeds to a minimum.

• Remove infected plants.

Anthracnose can affect other plants, too, including strawberries, corn, and lettuce. Providing good air circulation for your crops also helps keep anthracnose at bay.

Rust

Rust is another bad problem caused by a parasitic fungus. Rust attacks asparagus, corn, beans, and peas.

The first symptom is usually a blemish or lesion on the underside of lower leaves. Eventually it becomes more of a sore that opens and releases orange to red spores, hence the name.

There is no good cure. Commercial growers might use some heavy-duty fungicides, but home gardeners don’t want to go there. Instead, cut your losses by digging up the infected plants and disposing of them. In your next attempt, plant in new or different beds and look for resistant varieties.

Fusarium Wilt

Fusarium wilt is tricky because the fusarium fungus can live in the soil for years without showing itself in plants. But when plants it likes, including members of the Cucurbit family, are planted in the infected soil, the fusarium fungus easily enters the plants through their roots.

Plants can be infected at several stages of their development, including just after germination when it results in damping off. Older plants might wilt, appear to recover, and wilt again. Later the leaves start to turn yellow or brown, and eventually the whole plant just dies. Sometimes, when conditions are particularly wet and humid, you might see a pale pink powdery residue on the leaves and stems.

There’s not much you can do about the disease after the plants are infected. Prevention is the key. The only defense is a good offense—plant resistant varieties. If you have a crop of fusarium-infected plants, don’t plant any more Cucurbits in that spot for a few years.

Mildew

The two major mildew diseases are caused by different fungal infections. Powdery mildew, which affects cucumbers, squash, and onions, tends to hit new growth and particularly blossoms, which often dry up, so no fruit is set. The mildew grows on the surface of leaves, which will look dark and dirty and feel kind of sooty.

Downy mildew is actually a parasite that grows inside plants, especially cucumbers, beans, and onions. It produces purple and black spots on leaves and a gray mold on fruits. Downy mildew weakens plants so they produce less.

A few mildew-killing fungicides on the market are marketed as safe for vegetable gardens. Most contain copper and sulfur. Be sure to read labels carefully before using. Both mildew fungi can live in old garden debris, so good garden hygiene is a must.

Compost Pile

It should go without saying, but always wash any fruits or vegetables that come from treated plants. You don’t want to ingest any of the fungicide.

Coping With Germination Problems

When seeds don’t grow, it could be because of a limited number of reasons:

• The seed is old.

• The seed is infected.

• It is planted too deep.

• It was washed away in the rain or by heavy irrigation.

• Birds got it.

• It was burned by fertilizer.

• Too much moisture.

• Not enough moisture.

• Too cold.

• Too hot.

• Residual preemergent herbicide in soil.

Sometimes it’s a combination of things that prevents seed from germinating. But if you see a big flock of crows or starlings land in the garden right after you plant, and the seeds don’t sprout, I think you’ll know what the problem was.

Seedling Situations

So your seeds have all germinated and the little sprouts have gotten off to a fine start when, all of a sudden, they’re failing to thrive or even dying. What happened? Following are possibilities for what might have gone wrong:

• Too cold or too hot

• Too much water

• Not enough water

• Not enough sunlight

• Too much fertilizer

• Not enough fertilizer

• Insect attacks

• Damping off

• Residual herbicide in the soil

Not all these conditions result in dead plants. But you need to correct those things that can be corrected—and quickly, if you want to save your newly planted crops.

Lousy Leaves

The appearance of a plant’s leaves gives some pretty clear indications of its overall health. The occasional nibbled edge or a yellow leaf or two is not a sign that the plant is in deep trouble. If, on the other hand, all the leaves are turning yellow or if more leaves have holes than don’t, you can be pretty sure the plant is in big trouble.

Any number of issues show themselves in the foliage—disease, insect infestation, lack of nitrogen or another crucial element. The trick is to make the correct diagnosis.

Yellow Leaves

Yellow leaves are one of the most common symptoms that indicate something is wrong with your plant. And diagnosis can be a little tricky with yellow leaves.

If many of the leaves are yellow, it can mean the plant isn’t getting enough nitrogen, the weather is too hot, or there’s not enough sunlight.

Food for Thought

Occasionally, too much sunlight can be the culprit that causes leaves to yellow. Although most edible plants want full sun all day, some plants might find themselves suddenly in a sunnier situation than they were used to. This might happen if, for example, you were growing corn next to some kale. If you’ve harvested the corn and the kale is no longer shaded by the corn, its leaves might turn yellow.

If only the newest leaves are yellow, it might mean that the plant is getting too much fertilizer or it has an iron or manganese deficiency.

When older leaves turn yellow, it could mean there’s not enough nitrogen (or iron or manganese), the plant is being watered too often, or it has root rot problems. But sometimes yellow older leaves mean that the leaves are getting ready to drop off anyway. If the plant has plenty of healthy-looking newer leaves, it’s probably fine.

Sticky Leaves

When you find black or brown sticky stuff on your plants’ leaves, you know that you’ll find some kind of insect infestation. That sticky stuff is called frass or honeydew, and it’s basically insect poop.

Keep your eyes open for the insects that are leaving their calling cards behind. Then refer to Chapter 21 to find out what to do with your insect problems.

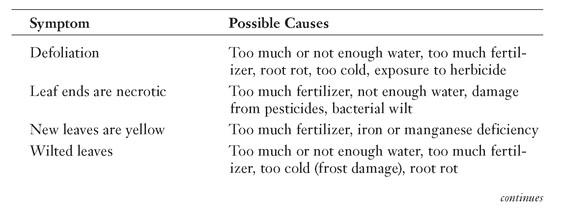

Other Problem Leaves

So many things can go wrong with plants, and much of it will show up in the leaves. The following table lists a few symptoms to look for.

We’ve described the seemingly endless things that can make your vegetable plants very sick, and even kill them, but don’t be discouraged. Some plants do die quickly, and you’ll have to replant or give up on that particular vegetable, but others will look terrible while continuing to produce prodigiously.

The Least You Need to Know

• Look for disease-resistant seeds and seedlings.

• Always buy certified disease-free seeds and seedlings.

• Avoid working in the garden when it’s wet.

• Practice good garden hygiene.

• Rotate crops every year to avoid soil-born and insect-spread diseases.

• Consult a garden professional when you can’t figure out what’s troubling your plants.