Chapter 5

Location Is Key

In This Chapter

• How much space does your garden need?

• Where’s the water?

• Factor in your neighbors, animals, and kids

• Avoiding wet, dry, and toxic areas

• A look at USDA plant hardiness zones

Think of the garden you’re planning as a piece of real estate. Then remember everything you’ve ever heard about buying real estate. It’s all about location, location, location. You might have great ideas, lots of resources, and the skills to match, but if you put your garden in the wrong spot, don’t expect good results. The better the location, the better the return. It’s just like buying a house.

Finding the right location for a vegetable garden is even more critical than if you were growing an ornamental garden of flowers. If you’re simply planting flowering plants and shrubs, you can adapt plant selections to the location—full shade, part shade, full sun, dry, soggy, hilly, rocky, etc. You can simply find the plants that like the situation you have. But if you want to grow tomatoes and cucumbers, you have to have good drainage and full sun. To get an abundant harvest of fresh herbs, you need to plant them in a place where the dog does not go. There’s no getting around it.

In this chapter, we look at some important factors to consider as you contemplate the location of your vegetable patch.

Put It Where the Sun Does Shine

Sunlight is essential for most plants to grow. Nearly all vegetables and fruits and most herbs require at least 6 hours of full sun every day to photosynthesize and thus produce their produce. This is pretty much non-negotiable.

Prof. Price’s Pointers

Most of the things we eat are part of a plant’s reproductive or storage organs: leaves, fruits, seeds, tubers, and roots. All these represent a huge investment in carbohydrates (sugars and starch), which come directly or indirectly from photosynthesis, which requires light. Photosynthesis is the conversion of light energy into the energy that makes plants grow.

You have to know where the sun shines on your property so you can grow your plants in full sun. Sounds simple, right? But if you remember sixth-grade science, you know the sun’s path changes over the course of the year.

To figure out the best spot for maximum sun exposure, spend the day watching the sun move across your yard. If you do this in early spring before the trees leaf out, be sure to allow for the shade produced by the tree canopies. I can’t tell you how many novice gardeners are shocked to find that the garden they spent so much time preparing is in full shade by 2 P.M. after the leaves have grown.

Enough Room to Grow

How much space your garden needs depends entirely on what you want to grow in it. If you’ve always wanted to experiment with several varieties of corn, you’ll need land, lots of land. If having a steady supply of fresh herbs is the full extent of your plans, you can get by with a few pots on the terrace.

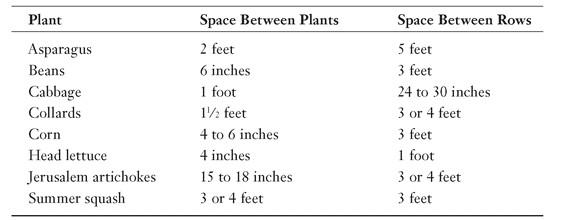

Your garden style (see Chapter 3) determines the square footage, or acreage, you need to achieve your goals. To help you estimate how much room you need, consider the space requirements of a few favorite plants. The following table shows how much space some common plants need.

Access to Water

In a perfect world, gardeners rely on rain to irrigate their gardens. But there’s no such thing as a perfect world. Southeastern Pennsylvania, where I live, recently experienced 3 years of serious drought conditions. And we’re not alone. Many parts of the country have on-going drought issues. Ornamental gardeners can add plant varieties that require less water, but vegetable growers have to resort to various methods of irrigation when Mother Nature is less than generous.

Unless you own stock in a company that makes garden hoses, you won’t want to run miles of hose to get water to the garden beds. So it’s important to locate the garden close enough to a reliable water source.

Food for Thought

If you’ll be spending long hours working in your garden, you might need to use a bathroom from time to time. Be sure to factor that into your location equation.

What Will the Neighbors Think?

If you have acres of land with no neighbors in sight, the location of your garden in relation to property lines is probably irrelevant. But most folks do have neighbors, and it’s important to consider the impact your garden will have on them.

First, if you spend all your waking hours raising vegetables and you’re heavily into power equipment, be sure not to put your garden a few feet from your neighbor’s patio. Think about your garden as an attractive diversion for neighborhood children, and protect your interests by making it inaccessible to them.

In a neighborhood where manicured lawns and well-tended beds are the norm, you might not want to locate your basic, utilitarian-style vegetable plot smack dab in the middle of the front lawn. (Some neighborhoods might have restrictions against this, too, so check with your neighborhood association, if you have one.)

Food for Thought

Remember that noise is a form of pollution. To keep it at a minimum, try to limit your use of power equipment, especially early in the morning, at dinnertime, or any time you see your neighbors enjoying their outdoor spaces. It’s the right thing to do.

Also be considerate when it comes to smelly activities. Can you imagine your neighbor starting to greet guests to his daughter’s engagement party in his backyard, and your load of fresh manure is delivered at the same time?

Consider the placement of your compost pile, too. Well-constructed, healthy compost bins and piles shouldn’t have a bad smell, but they don’t always function as they should. Try to place your compost well away from downwind neighbors.

Try to keep the unsightly aspects of your gardening efforts away from your neighbors’ sightlines. No one wants a good view of dirt piles, a wheelbarrow full of weeds, or an overflowing compost bin.

©iStockphoto.com/Eira Fogelberg

It all boils down to using common sense and being considerate of others. If you play by those rules, you’ll find the right location for your garden.

Out of Harm’s Way

Plants don’t do well in traffic, whether it’s four-wheeled or four-legged, so when you’re thinking of locations for your garden, you need to assess a number of important traffic factors, including vehicles, animals, and kids.

Most people don’t intentionally drive cars through their gardens. Unfortunately, sometimes cars stray off the pavement. If you place your garden too near a driveway, it could be damaged by a not-quite-tight-enough turn or an overestimated back-up effort. Snowplows can overstep the pavement, too, resulting in compacted soil and crushed crowns on perennial plants. Bikes, trikes, and wagons also pose a threat to gardens.

To avoid death by vehicle in the garden, select a location well away from traffic patterns. This includes places where the kids have always thrown their bikes, the natural path you take from house to garage or shed, near a turn-around or back-up area of the driveway, or where the snowplows regularly push piles of snow.

Dealing With Four-Legged Friends

Fido might be your best friend, but dogs and gardens aren’t great together. It’s not that dogs mean harm, but let’s face it, if your dog pees or poops on the asparagus, it becomes less than appetizing. In fact, the acids in dog urine can eat right through tree bark, so just think what a regular visit will do to plants with thinner skins. Not a pretty picture.

And animal excrement from meat-eaters like dogs and cats is not healthy stuff. All kinds of nasty microorganisms can live in it, so if, despite your precautions, your dog or the neighbor’s cat has made deposits in your garden, remove it promptly to avoid the risk of contamination and illness.

If your dog has the run of the yard, you might have to fence the garden (see Chapter 6). Dog owners who use electronic invisible fences to contain their animals should put their gardens outside the electric perimeter if possible.

Garden Guru Says

Here’s an easy, no-mess way to clean up after dogs or cats who have used your garden as a potty: put your hand inside a plastic bag, pick up the poop with your plastic-covered hand, and using your other hand, turn the bag inside out. Tie the top of the bag closed, and dispose of it in the trash.

Cats are another animal all together. The location of the garden has no impact on a cat’s ability to use it for a litter box. (See Chapter 12 for some hints on cat control.)

Dealing With Four-Legged Foes

While many warm-blooded pests can wreak havoc in your garden (and some of these are addressed in Chapter 21), deer are the worst. Many farmers and gardeners in my neck of the woods have long-running battles with these “rats with hooves,” as they call them. If you live in an area with a large deer population, just forget about having a successful garden without fencing. (Some more strategies for dealing with deer are discussed in Chapter 21.)

You would be wise not place your garden in a spot where you regularly see a large herd of deer grazing. But other than that, the garden location won’t make much difference when it comes to these marauders.

Kids Rule

We love it when our children romp in the yard. It’s wholesome and healthy, and it deters them from sitting inside watching TV, playing video games, or sitting in front of the computer. But although gardens are nice places, they’re not always the safest place for a young child to be.

Chemical herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers can be toxic to small ones. Just touching leaves or fruits that have been treated can cause allergic reactions. And because really little kids often put their hands in their mouths, the possibility of them ingesting toxic products is high. Even organic products like pyrethrins or iron phosphates can make a child sick if they are swallowed. Garden tools, especially pruners and knives, can also be extremely dangerous in the hands of youngsters. To avoid accidents, never leave very young children unattended in the garden. Teach them to respect tools and instruct even the tiniest ones always to wash fresh produce before eating it.

If you have small children, it’s a good idea to place the garden in a spot where you have control over who comes and goes in it. So I can watch the kids and work in the garden simultaneously, I located my garden within sight of their play area.

Garden Guru Says

When your children have graduated from swing sets and sandboxes, you can reuse the space and recycle the equipment. The sandbox can become a raised bed planter or even a modified square-foot garden (see Chapter 12). Use the swing set legs and cross bars as a support system for climbing plants like beans and peas. You can also reuse an old dog pen as a garden space, with the fencing recycled as plant supports. You’ll have to do some extra soil preparation in these spots, though. (See Chapters 8 and 9 for information on testing and preparing the soil.)

Environmental Factors

If your property is small, you may not have much choice in where to put the garden. It’s either right here or nowhere. Larger lots, on the other hand, might have any number of sunny, childfree, dog-proof options.

The deciding factors might be environmental. Some issues could include the relative sogginess or dryness of the soil, previous uses of the land, wind patterns, proximity of tree roots, slopes, erosion, and lack of topsoil.

“Wet Feet”

Most of the plants we look at in this book prefer to grow in well-drained soil, so don’t set up your garden in the swampy part of your yard or at the end of the sump pump drainpipe. Without elaborate modifications and drains, a wet yard will never support a successful vegetable garden.

Garden Guru Says

Watercress is one edible plant that likes to have what gardening types call “wet feet”—that is, soggy soil that retains moisture and rarely dries out completely. (In the wild, watercress grows in streams.)

Dry as a Bone

Some properties have sections that are dryer than others. Sandy soils that drain very quickly dry out fast and might not retain enough moisture to satisfy the plants’ need for water. Chalky soils tend to be dry, too.

If the only land you have fits in this category, you’ll need to do some heavy-duty soil amending. However, if there’s another, less-desertlike location on your property, maybe use that instead.

Superfund Sites

Superfund sites are no laughing matter. Hundreds of sites around the country have seriously contaminated soil caused by toxic waste dumping. Some of that land has been cleaned and reclaimed. Other parts are still contaminated.

Not all contaminated sites have been placed on the Superfund list. Some have yet to be identified. If you don’t know who previously owned your property or what it was used for, find out before you start a vegetable garden. Be especially vigilant if your property fits any of the following descriptions:

Compost Pile

Properties that border heavily traveled roads might have lead contamination in the soil. If your garden is near a highway or a congested traffic area, have the soil tested for lead before growing edible plants.

• Located near a gas station or a former gas station

• Adjacent to an active or former military base

• Near any existing or former manufacturing plant

• Near an existing or former dump or landfill

• Close to a junkyard or automobile salvage facility

• On a former farm

Although the chances of your property being contaminated are small, you don’t want to find out about it after you’ve consumed a few years’ worth of harvests. To find out if your property is near a Superfund site, log on to the Environmental Protection Agency’s website at epa.gov/superfund/sites. Here you’ll find a county-by-county guide to hazardous waste sites, the names and addresses of the sites (including aliases), and what action has been taken to clean them up.

Toxic Trees

In addition to making shade, some trees add other obstacles to successful vegetable gardening. Trees whose roots grow close to the surface and reach out in a wide circle (known as the drip line) are not good companions for your vegetable garden. The roots will interfere with cultivation and suck up moisture greedily. Most maple trees are in this category, with silver maples ranked as the worst culprit.

Black walnut trees are also bad neighbors for your garden. In fact, their roots produce a toxin that’s deadly for a wide range of plants, including many vegetables. (The toxin can also have an allergic effect on humans and horses.) The Ohio State University, West Virginia University, and Purdue University’s extension services have published fact sheets about black walnut toxicity. They include a list of plants that will not grow within a 50-foot radius—and in some cases, up to an 80-foot radius—of the trunk of a black walnut tree. Research shows that these plants will be injured or killed within 1 or 2 months of growth in proximity to this tree.

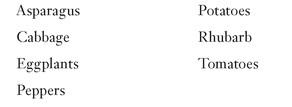

Some susceptible plants include the following:

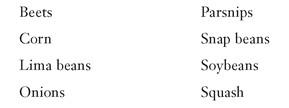

These plants don’t seem to mind the toxin:

If you remove a black walnut tree to plant a garden, pull out the roots and then wait about 2 months for the toxins to break down before you plant anything.

USDA Plant Hardiness Zones

If you’ve ever read a how-to gardening book or looked through a plant catalog, you’ve probably seen a USDA Plant Hardiness Zone map. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) created the map in 1960 based on more than 60 years of temperature data. It was revised in 1965 and again in 1990. In 2003, the U.S. National Arboretum created an online version, and in 2006 The National Arbor Day Foundation updated the zones. Some subtle differences exist in the various versions that have to do with environmental warming trends.

The map was designed to help gardeners and farmers determine what will grow where, when. The map is based on the average lowest winter temperatures throughout the country. Years ago, there were 10 zones, but the USDA expanded the number to 20 by adding “a” and “b” zones to zones 2 through 10, and also adding zone 11.

To find which hardiness zone your garden is in, go to usna.usda.gov/Hardzone, or arborday.org/media/zones.cfm.

Food for Thought

Within the USDA zones are microclimates—sort of zones within zones—where the range of temperatures are slightly higher or lower than indicated on the USDA map, due to environmental and geographic factors. These factors can hange from year to year. For example, my home in southeastern Pennsylvania is in zone 6b. But because my garden sits below street level, faces south and east, and is protected on all four sides with fences and white plaster walls that reflect the sun, the garden behaves more as if it were in zone 7a. Other factors that might create a microclimate include prevailing winds and proximity to lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, mountains, hills, factories, and highways.

Knowing the hardiness of plants is particularly important when you buy them from websites or catalogs as opposed to your local garden center. Many companies ship plants based on a formula of your order date and your hardiness zone. For example, the Burpee website says that if you live in zone 7, your vegetable plants will arrive between April 20 and April 28. Perennials are shipped by March 16. It’s a good system.

The Least You Need to Know

• Edible plants need at least 6 hours of sunlight a day, so locate your garden to allow them their due light.

• By calculating how much room each plant variety will require to grow, you can easily determine what you can plant in the space you have.

• Put your garden conveniently close to a water source so you won’t have to haul water back and forth.

• Don’t allow young, unattended children or pets access to your garden. It’s just not safe for everyone involved.

• Determine prior uses of your property to protect against contamination.

• Know your zone. Your plants will thank you for it.