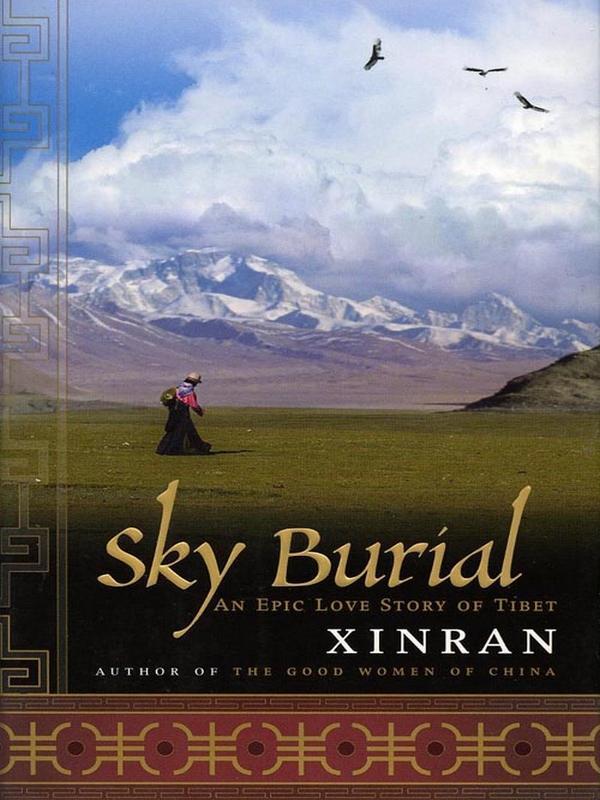

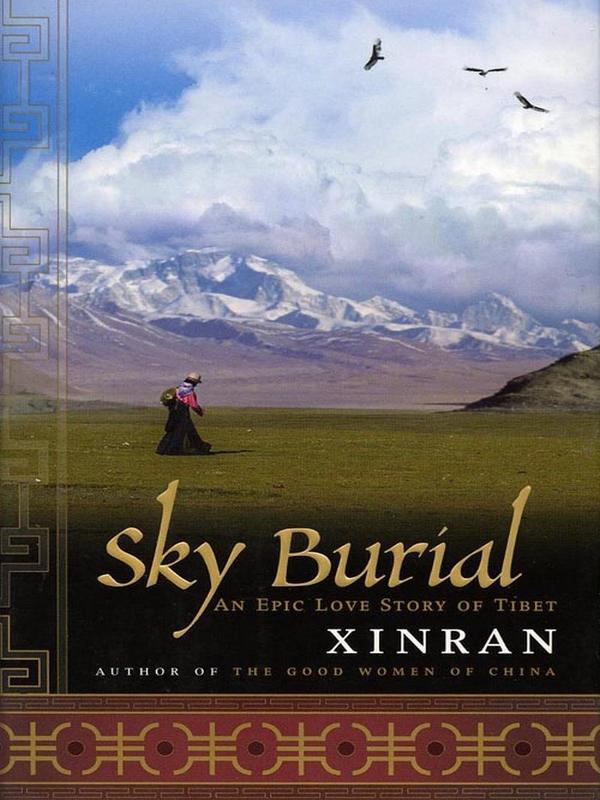

In the world of fiction reviewing, extraordinary is an over-used word. Yet there really is no other way to describe Chinese author Xinran's second book, Sky Burial. It is extraordinary in so many ways-the subject matter, the setting, the central character, but mostly its authenticity and the author's continuing search for the woman whose life is told here.

Sky Burial is the true story of a Chinese woman's 30-year search through Tibet for news of her lost, presumed dead, husband. Xinran is working as a radio journalist on a women's programme when a listener calls in to tell her about Shuwen. Xinran travels hundreds of miles across China to interview her and, over two days, Shuwen opens her heart and reveals her tragic, scarcely imaginable life story. Xinran returns to her life and spends the subsequent 10 years trying to find Shuwen again, researching her story and writing this book-a homage to an ordinary woman's extraordinary life-long search for the truth.

The story is a simple one: Shuwen meets her intelligent, idealistic husband-to-be while they are both training to be doctors. After less than 100 days of marriage, Kejun travels to Tibet as a Chinese army doctor and before long, Shuwen is notified that he has died in an "incident". Shuwen decides to join the army herself, travel to Tibet and find out if he really is dead, and if so, how and why he died.

And then, as if travelling to a closed country like Tibet as a young woman in the 1950s is not difficult enough, Shuwen quickly becomes separated from her unit and, close to death herself, is taken in by a family of Tibetan nomads. Her transformation from Chinese doctor to nomadic Buddhist is a long, painful and at many turns, deeply distressing one.

Sky Burial is a slight book-little more than an extended short story-and yet the ground it covers is immense, not just because of the fascinating glimpse it offers into a land and a people still largely unknown in the West. Despite its tragic themes of loss and survival in one of the world's harshest landscapes, it is an uplifting tale of unwavering loyalty and immeasurable inner strength. -Carey Green

Xinran Xue

Sky Burial, An Epic Love Story of Tibet

© 2004

Translated from Chinese by Julia Lovell and Esther Tyldesley

For Toby

who knows how to share

love and experience

space and silence

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This version of Sky Burial differs slightly from the Chinese original. During the translation process, the author worked with her translators and editor to make sure that all elements of the book were accessible to non-Chinese readers.

In Chinese names, the surname is placed before the first name. Shu Wen’s first name is therefore Wen.

In 1994 I was working as a journalist in Nanjing. During the week, I presented a nightly radio program that discussed various aspects of Chinese women’s lives. One of my listeners called me from Suzhou to say that he had met a strange woman in the street. They had both been buying rice soup from a street vendor and had started talking. The woman had just come back from Tibet. He thought that I might find it interesting to interview her. She was called Shu Wen. He gave me the name of the small hotel where she was staying.

My curiosity awakened, I made the four-hour bus journey from Nanjing to the busy town of Suzhou, which despite modern redevelopment still retains its beauty-its canals, its pretty courtyard houses with their moon gates and decorated eaves, its water gardens, and its ancient tradition of silk making. There, in a teahouse belonging to the small hotel next door, I found an old woman dressed in Tibetan clothing, smelling strongly of old leather, rancid milk, and animal dung. Her gray hair hung in two untidy plaits and her skin was lined and weather-beaten. Yet, although she seemed so Tibetan, she had the facial characteristics of a Chinese woman-a small, slightly snub nose, an “apricot mouth.” When she began to speak, her accent immediately confirmed to me that she was indeed Chinese. What, then, explained her Tibetan appearance?

For two days, I listened to her story. When I returned to Nanjing my head was reeling. I realized that I had just met one of the most exceptional women I would ever know.

I never saw her again, but her story did not leave my mind, so finally I felt I must share it with others.

1 SHU WEN

Her inscrutable eyes looked past me at the world outside the window-the crowded street, the noisy traffic, the regimented lines of modern tower blocks. What could she see there that held such interest? I tried to draw her attention back.

“How long were you in Tibet?”

“More than thirty years,” she said softly.

“Thirty years! But why did you go there? For what?”

“For love,” she answered simply, again looking far beyond me at the empty sky outside.

“For love?”

“My husband was a doctor in the People’s Liberation Army. His unit was sent to Tibet. Two months later, I received notification that he had been lost in action. We had been married for less than a hundred days.

“I refused to accept that he was dead,” she continued. “No one at the military headquarters could tell me anything about how he had died. The only thing I could think of was to go to Tibet myself and find him.”

I stared at her in disbelief. I could not imagine how a young woman at that time could have dreamed of traveling to a place as distant and as terrifying as Tibet. I myself had been on a short journalistic assignment to the eastern edge of Tibet in 1984. I had been overwhelmed by the altitude, the empty awe-inspiring landscape, and the harsh living conditions.

“I was a young woman in love,” she said. “I did not think about what I might be facing. I just wanted to find my husband.”

I had heard many love stories from callers to my radio program, but never one like this. My listeners were used to a society where it was traditional to suppress emotions and hide one’s thoughts. I had not imagined that the young people of my mother’s generation could love each other so passionately. People did not talk much about that time, still less about the bloody conflict between the Tibetans and the Chinese. I yearned to know this woman’s story, which came from a time when China was recovering from the previous decade’s devastating civil war between the Nationalists and Communists, and Mao was rebuilding the motherland.

“How did you meet your husband?”

“In Nanjing,” she replied, her eyes softening slightly. “I was born there. Kejun and I met at medical school.”

That morning, Shu Wen told me about her youth. She spoke like a woman who was unused to conversation, pausing often and gazing into the distance. But even after all this time, her words burned with love for her husband.

“I was seventeen when the Communists took control of the whole country in 1949. I remember being swept up in the wave of optimism that was flooding China. My father worked as a clerk in a Western company. He hadn’t been to school, but he had taught himself. He believed strongly that my sister and I should receive an education. We were very lucky. Most of the population at this time were illiterate peasants. I went to a missionary school and then to Jingling Girls College to study medicine. The school had been started by an American woman in 1915. At that time there were only five Chinese students. When I was there, there were more than one hundred. After two years, I was able to go to the university to study medicine. I chose to specialize in dermatology.

“Kejun and I met when he was twenty-five and I was twenty-two. When I first saw him, he was acting as a laboratory assistant to the teacher in a dissection class. I had never seen a human being cut up before. I hid like a frightened animal behind my classmates, too nervous even to look at the white corpse soaked in formalin. Kejun kept catching my eye and smiling. He seemed to understand and sympathize with me. Later that day, he came looking for me. He loaned me a book of colored anatomy diagrams. He told me that I would conquer my fear if I studied them first. He was right. After reading the book several times over, I found the next dissection class much easier. From then on, Kejun patiently answered all my questions. Soon he became more than a big brother or a teacher to me. I began to love him with all my heart.”

Shu Wen’s eyes were so still-locked on something I couldn’t see.

“Everybody admired Kejun,” she continued. “He had lost all his relatives during the Sino-Japanese War, and the government had paid for him to go to medical school. Because he was determined to repay this debt, he worked hard and was an outstanding student. But he was also kind and gentle to everyone around him, particularly to me. I was so happy… Then Kejun’s professor came back from a visit to the battlefields of the Korean War and told Kejun of how the brave soldiers who were hurt and crippled in those terrible battles had to do without doctors and medicine, how nine out of ten of them died. The professor said he would have stayed there to help if he hadn’t thought it his responsibility to pass on his medical knowledge to a new generation, so that more hospitals could have trained surgical staff. In war, medicine was the only lifeline: whatever the rights and wrongs of combat, saving the dying and helping the wounded were heroic acts.

“Kejun was deeply impressed by what his mentor had told him. He talked to me about it. The army was in desperate need of surgeons to help its wounded. He felt he ought to join up. Although I was frightened for him, I didn’t want to hold him back. We were all suffering hardship at that time, but we knew it was for the greater good of the country. Everything was changing in China. Many people were packing their bags and heading for poor rural areas to carry out land reform, or going to the barren, uninhabited borderlands to turn the wilderness into fields. They went to the northeast and northwest to look for oil, or deep into the mountains and forests to fell trees and build railways. We regarded separation from our loved ones as a chance to demonstrate our loyalty to the motherland.”

SHU WEN didn’t tell me where Kejun’s first army posting was. Perhaps she didn’t know. What she did say was that he was away for two years.

I asked her whether she and Kejun wrote to each other. Shu Wen gave me one of her hard looks that made me ashamed of my ignorance.

“What kind of postal system do you imagine there was?” she asked. “War had created enormous upheaval. All over China, women were longing for news of husbands, brothers, and sons. I was not the only one. I had to suffer in silence.

“I heard nothing from Kejun for two years. Separation was not romantic, as I had imagined-it was agony. The time crawled past. I thought I was going to go mad. But then Kejun returned, decorated with medals. His unit had sent him back to Nanjing to take an advanced course in Tibetan language and medicine.

“Over the next two years our love grew stronger. We talked about everything, encouraging and advising each other. Life in China seemed to be getting better day by day. Everybody had a job. They worked not for capitalist bosses but for the government and the motherland. There were free schools and hospitals. We were told that, through Chairman Mao’s policies, China’s economy would catch up with those of Britain and America in only twenty years. We also had the freedom to choose whom we would marry, rather than obeying the choices of our parents. I told Kejun about how our friend Mei had, to everyone’s surprise, married Li, an unsophisticated country boy, and how Minhua, who seemed so meek, had eloped with Dalu, the head of the student council. Their parents had come to the university to complain. But I didn’t tell him how, while he was away, I had had other admirers, and people had advised me not to pin my hopes on a man who risked death on the battlefield.”

“WHEN KEJUN finished his studies, we decided to get married. He was awaiting orders from the military headquarters in Nanjing. I was working as a dermatologist at a big Nanjing hospital. In the eyes of our friends, many of whom had children, we had already waited late enough to marry. Kejun was twenty-nine, I was twenty-six. So we applied to the Party for permission. Although my father found it difficult to get used to the idea of free choice in marriage, he was very fond of Kejun and knew I had made a good decision. In any case, if I delayed marriage any longer, he would lose face. My older sister had already got married and had moved to Suzhou, taking my parents with her.

“Our wedding was celebrated in true ‘revolutionary style.’ A high-ranking political cadre was the witness and friends and colleagues wearing little red paper flowers were our escorts. For the refreshments we had three packets of Hengda cigarettes and some fruit candies. Afterward we moved into the hospital’s married quarters. All we owned were two single wooden plank beds, two single quilts, a rosewood chest, a red paper cutout of two ‘happiness’ characters, and our marriage certificate decorated with a portrait of Chairman Mao. But we were ecstatically happy. Then, only three weeks later, Kejun’s call-up papers arrived. His unit was to be posted to Tibet.

“We hardly had time to absorb the news before he left. The army arranged for me to be transferred to a hospital in Suzhou so that I could be close to my parents and sister. We hadn’t requested a transfer but the Party organization said that it was only right that army dependents should have their families to look after them. I threw myself into my work so that I didn’t think about how much I was missing Kejun. At night, when everyone else was asleep, I would take out Kejun’s photograph and look at his smiling face. I thought all the time about what he had said just before he left: that he’d be back soon because he was anxious to be a good son to my parents and a good father to our children. I longed for him to return. But instead I received a summons to the Suzhou military headquarters to be told that he was dead.”

We sat in silence together for some time. I did not want to interrupt her thoughts.

THAT NIGHT, Shu Wen and I shared a room in the small hotel next to the teahouse. During the two days we spent together, she opened up to me in a way that I had hardly dared hope.

But a few days later, when I called the hotel in Suzhou, she had already left. In a panic, I contacted the man who had called me about her.

“I don’t know where she’s gone,” he said. “The other day she sent me a packet of green tea via the rice seller to say thank you for introducing her to Xinran. She said she hoped you would tell people her story. Since then I haven’t met her again.”

It was not until I went to Tibet again in 1995 to make a documentary that I began to understand what it might be like to live there. I and my four cameramen were rendered speechless by the emptiness of the landscape, the invisible wind that swept across the barren land, the high boundless sky, and the utter silence. My mind and soul felt clean and empty. I lost any sense of where I was or of the need to talk. The simple words that Shu Wen had used-“cold,” “color,” “season,” “loss”-had a new resonance.

As I wrote Shu Wen’s story, I tried to relive her journey from 1950s China to Tibet-to see what she saw, to feel what she felt, to think what she thought. I deeply regretted having allowed Wen to leave without telling me how I could find her again. Her disappearance continues to haunt me. I dearly wish that this book might bring her back to me and that she will come to know that people all over the world are reading her story.

2 I CAN’T LEAVE HIM IN TIBET, ALONE

Death Notice

This is to certify that Comrade Wang

Kejun died in an incident in the east of

Tibet on 24 March 1958, aged 29.

Issued by the Suzhou Military Office,

Jiangsu Province, 2 June 1958

Wen stood stunned on the steps of the military headquarters, the summer rain of the Yangtze delta monsoon drenching her hair and face.

Kejun, dead? Her husband of less than a hundred days, dead? The sweetness of those first days after their marriage lingered in her heart. She could still feel their warmth. Of those hundred days, they had only spent three weeks together. It was impossible that he was dead.

He had been so strong, so talkative, so full of life when he set out for Tibet. An army doctor wouldn’t have been directly involved in the fighting. What “incident” was this? How did he die? Why could nobody give her any information? They had not even added a few words to testify that he died a revolutionary martyr as they always did for soldiers who fell in battle. Why not?

In the flood of buoyant “Reports of Victory from the People’s Liberation Army on Entering Tibet,” there had been no mention of an incident in which Kejun could have died. Staff at the military office responsible for comforting the widows and orphans of fallen soldiers had told Wen privately that they hadn’t received any of the standard battlefield bulletins from Tibet.

Wen stood in the Suzhou street, unheeding of the rain. The busy life of the town continued around her, but she noticed nothing. An hour passed, then another. She was soaked in sorrow and bewilderment.

The chiming bells of Cold Mountain Temple called her back from her grief. Returning to the hospital where she worked, truly alone for the first time, a thought flashed through her mind. What if Kejun had simply been separated from his unit, like all those soldiers who were mistakenly reported dead when they were actually on their way home? Perhaps he was in danger or had fallen ill. She couldn’t leave him in Tibet, alone.

THE IDEA, conceived in that chill rain, that she should go and find Kejun proved to be so powerful that, despite all the attempts of her family, friends, and colleagues to talk her out of it, Wen was determined to join her husband’s regiment and travel to Tibet. She rushed around every government office she could find, tearfully thrusting her marriage certificate, Kejun’s parting note, even his few personal possessions-his towel, handkerchief, and tea mug-at everyone she saw. “My husband must be alive,” she insisted. “He wouldn’t abandon his new wife and the future mother of his children.”

At first the military officials she talked to tried to dissuade her from joining the army, but when they heard she was a doctor, they stopped protesting. The army was desperately short of doctors and many of the soldiers in Tibet were suffering from altitude sickness. Her qualifications as a dermatologist made her even more useful: there were many severe cases of sunburn because of the high altitude. It was decided that Wen should set out for Tibet immediately. The urgent need for doctors and her own eagerness to start looking for Kejun as soon as possible made the long training undertaken by her husband an unnecessary luxury.

The day came when Wen was due to leave Suzhou. Her big sister and elderly parents took her to the long-distance-bus station by the river. No one said a word. No one knew what to say. Her sister pressed into Wen’s hand a shoulder bag made of Suzhou silk, without telling her what was inside; her father quietly placed a book inside her newly issued army rucksack; her mother tucked a tear-soaked handkerchief into the appliqué fastening of Wen’s blouse. With tears in her eyes, Wen handed her marriage certificate to her mother. Only a mother could be entrusted with something so important. She gave Kejun’s tea mug and towel to her father, knowing how much he loved his son-in-law. She then gave her sister-who knew all Wen’s secrets-a package containing Kejun’s correspondence and documents, along with their love letters.

Dark, gloomy clouds merged with cooking smoke from the white-walled, gray-tiled local houses and gently enveloped Wen’s family as they watched her climb onto the bus. Through the shuddering picture frame of the bus window, Wen saw her family grow smaller and smaller, and finally disappear from sight. She took her last look at Suzhou: the houses with little bridges over flowing water; the temples on the hillsides overlooking the water; the lush greens of the Yangtze delta. There were red flags everywhere, fluttering in the breeze.

When Wen opened the silk shoulder bag her sister had given her, she found inside five tea-boiled eggs, still warm; two pieces of sesame cake; a bag of pumpkin seeds; a bag of dried sweet-sour turnip slivers; a flask of tea; and a little note, the characters blurred by tears:

My dear little sister,

My heart is heavier than words can say.

Our parents are no longer young and can’t

bear much more sorrow in their lives, so

come back soon. Even if you no longer

have Kejun, you still have us, and we can’t

live without you.

Be safe, take care!

I am waiting for you.

Your sister

The book her father had slipped into her bag turned out to be The Collected Essays of Liang Shiqiu. These essays, with their ability to turn the happenings of everyday life into gems of wisdom, were her father’s favorite reading. He had written an inscription on the title page:

Little Wen,

Just as books are read one word at a time,

roads are taken one step at a time.

By the time you’ve finished reading your

book, you and Kejun will be taking the

road home.

Your mother and father await your return.

Wen folded her sister’s note into a paper crane and, along with a small photograph of Kejun, placed it inside the book as a mark, then wrapped the whole thing in her mother’s handkerchief. She’d been told that private property was forbidden on military expeditions, and so these few precious things were all she had to keep her memories alive.

The bus set off northward, along the Grand Canal, which linked Hangzhou with Beijing, bumping and jolting passengers whose excitement at the prospect of the journey, a rare event in their lives, had soon been replaced by fatigue. Gazing at the still waters of the canal, Wen suddenly remembered something her father once told her: that the 2,400-year-old canal linked the Yangtze, the Yellow River, and many of China’s other rivers, and that all of China’s major rivers flowed west to east and had their source in Tibet. This was her first connection to Kejun, this cold, deep canal, its waters originating in the land of glaciers and snowcapped mountains that had swallowed up her husband. She remembered the intense happiness of her first days of marriage. Early each morning, she had roused her husband gently from his dreams with a cup of green tea by his pillow. Each night, she had been soothed to sleep by his caresses. To be separated even for a moment was painful to them. At work, Wen always carried in the pocket of her hospital coat a message that Kejun had written for her that day:

It’s raining today. Please take an umbrella

and my love. Then I’ll have no need to

worry, no matter where you are, no rain

will soak your body…

Yesterday you coughed twice, so today you

must drink two cups of water, and this

evening I’ll make you a medicinal broth

to clear your lungs. Your health is the heart of

our home…

Wen, don’t worry, the home we talked

about yesterday will come. I will be a good

husband to you, and a good son to your

parents…

Hey, little girl, eat a few more mouthfuls of

food, you’re getting thin! I can’t bear to see

you fade away!

Tears poured down Wen’s face. The middleaged woman in the next seat took Wen’s handkerchief from the front of her blouse and placed it in her hand.

STOPPING AND starting for six days and five nights, the bus made its way northwest through a constant flow of vehicles, animals, and humans, before finally reaching Zhengzhou-a city near the Yellow River and China’s largest railway junction. Wen had been instructed to report to the army base there, then continue her journey by train to Chengdu, and finally enter Tibet by the great Sichuan-Tibet Highway. She had heard that Kejun’s unit had also entered the Tibetan plateau by this complicated route.

On arriving at the bus station, Wen was met by a soldier from the nearby army base. She was warmly welcomed and taken to her quarters. All the arrangements seemed thorough: although the beds in the dormitory were just wooden boards balanced on stools and slept six, the quilts and pillows looked spotless. Compared to the filthy street outside the window with its whirlwind of dust and piles of rubbish, it felt like paradise. The soldier sent to meet Wen told her they hardly ever saw any female soldiers-most women they accommodated at the base were family members looking for their men. His comment reminded Wen that she was now a member of the People’s Liberation Army, and no longer an ordinary civilian.

Behind a curtain of woven straw, Wen had a refreshing cold wash. She then changed into the uniform that had been waiting for her. As she tidied her hair, using a tiny shard of broken mirror stuck into the curtain, Wen pondered how well organized the army seemed. If it had been able to defeat the leader of the Nationalists, Chiang Kai-shek, why couldn’t it provide her with any information about Kejun?

The mirror was too small to show her what she looked like in her new uniform. She wondered if Kejun would recognize her. Then the accumulated exhaustion of six days of shaking and jolting on the long road overcame her and, even though it was only five o’clock in the evening, she threw herself on the bed and fell into a heavy sleep.

The one and only military reveille that Wen would hear in her entire life summoned her from a sleep so deep that it had left no room even for dreams. Beside her, five still-sleeping women lay sprawled over the bed. They weren’t wearing uniforms. Maybe they were administrative workers or women come to search for their relatives, thought Wen. When she sat up, another body rolled into the space she had left. No one else had been disturbed by the bugle, even though it went on for so long. They must have been more exhausted than she was. Not even a bomb would wake them, she thought.

Feeling that she’d regained a lot of her strength, Wen got down from the communal plank bed to discover that the new uniform she was wearing had been crushed into a mass of creases and wrinkles. If Kejun could have seen her, he would have given her a tap on the nose-the punishment he had meted out whenever Wen hadn’t been able to answer one of his questions. She had loved this “punishment” of hers. One touch of Kejun’s hand would suffuse her entire body with warmth. Often, she used to fudge her answers on purpose.

“Sleep well?” A man greeted her with a smile from the doorway, interrupting her thoughts. Wen could sense immediately from his bearing, and from the firm and direct way in which he had addressed her, that he was an official.

“I-I slept very well. Thank you,” she answered nervously.

The man introduced himself as Wang Liang and invited her to come and have breakfast.

“I can hear your stomach grumbling,” he remarked. “The soldier who brought you here said you didn’t come out of your room after your wash. Later on, a female comrade reported you were fast asleep, so we didn’t wake you for dinner. In times of war, a good night’s sleep is too precious to disturb.”

Wen warmed immediately to Wang Liang.

She ate her first northern-style breakfast: a bowl of hulatang-a glutinous soup made from wheat flour mixed with coarsely chopped pickled greens, pig’s offal, and lots of chili powder; there was also a cake of maize flour, very harsh to the mouth, and a lump of a very salty pickle made from mustard leaves, which they call “geda.” These crude, spicy flavors would normally have been bitter medicine to a southern girl weaned on more refined substances, but Wen’s stomach seemed already to have been disciplined by her military uniform and by hunger, and within minutes, she’d eaten her way through the helping of breakfast doled out to her, and knew she could easily polish off another two. But when Wang Liang asked if she wanted some more, Wen refused. Having read reports about the strict rationing still in force in the army, she knew that an extra helping for her would be snatched from the mouths of others.

After breakfast, Wen walked with Wang Liang to his office. Photographs of Mao Tse-tung and Zhu De in military uniform hung on the walls, giving the makeshift room an air of deep solemnity. The presence of a table and three chairs indicated that the office’s owner had the authority to hold meetings. On the walls of the room were painted the Three Great Regulations and the Eight Principles of the Liberation Army in bright red characters. Wen was already familiar with these army slogans, among them “Obey all orders,” “Do not take as much as a needle or a piece of thread from the masses,” “Don’t damage crops,” and “Don’t mistreat captives.”

Seated at his desk under the portraits of the great leaders, Wang Liang seemed serious and imposing. With great firmness, he tried to persuade Wen to change her mind about going to search for Kejun. He urged her to put aside her feelings for her husband, and to consider the difficulties and the dangers she would face if she traveled to Tibet: she couldn’t speak the language, she could easily lose her unit, the terrain and the altitude were making people ill, and the situation out there was extremely unpredictable. The casualty rates were high and, as a woman with no training, the chances of her surviving even a month were extremely low.

Wen looked Wang Liang in the eye. “When I married Kejun,” she said, “I pledged my life to him.”

Wang Liang bit his lower lip. He could see that Wen was not going to give up.

“You have a very stubborn heart,” he said. “There is a military train going to Chengdu tomorrow. You may board it.”

He handed her a booklet of military information on Tibet and Tibetan customs. Wen accepted them gratefully.

“Thank you, sir. I will study these hard during the journey and try to adapt to the conditions there.”

“War gives you no time to study and no chance to adapt,” Wang Liang remarked grimly as he got up and walked around to Wen. “It draws clear lines of love and hate between people. I’ve never understood how doctors manage to choose between professional duty and military orders. Whatever happens, remember one thing: just staying alive is a victory.”

Wen sensed Wang Liang was trying to frighten her. She nodded to show respect, but didn’t understand what he had meant. She gave her sister’s silk bag to Wang Liang: inside she had written the names of Kejun, her parents, her sister, and herself. She told Wang Liang that she hoped everyone inside the bag would be reunited in Suzhou. In return, Wang Liang gave Wen a pen and a diary. “Writing can be a source of strength,” he said. Wen had spent less than an hour in Wang Liang’s company, but his words were to remain with her throughout her life.

THE SO-CALLED army transport train turned out to be no more than a glorified goods train: each railroad car holding almost a hundred impossibly cramped people. The tiny windows, only twenty centimeters square, let in very little light. Wen, along with the only other female passenger, a nurse, was forced to huddle with the men. Before they got on the train, someone introduced the nurse to her: she was from Wenzhou and was eager to talk, but no one in the car, not even Wen, could understand what she was saying because of her thick Zhejiang accent. About once every four hours, the train would stop for five minutes in some desolate wilderness to give people a chance to empty their bladders and shake their arms and legs a bit. Sometimes, at night, it halted near a military supply station and they were given a proper meal, but otherwise, during the day the soldiers staved off their hunger pangs with biscuits and dry steamed buns.

To begin with, some of the soldiers were excited by the scenery whizzing past the tiny windows, but soon the lack of oxygen and the stifling heat inside the closed car sucked all the life out of them. Their only source of entertainment consisted in trying to get the Wenzhou nurse to produce her meaningless sounds. After a few hours of this, even she stopped talking.

Wen wasn’t in the mood for conversation. Her thoughts were entirely caught up with her search for Kejun. She couldn’t even face introducing herself to her fellow soldiers, terrified that the most basic question might send her into a state of emotional turmoil. She concentrated instead on reading the booklet Wang Liang had given her.

It spoke of nomadic tribes and the importance of religion in Tibetan culture. It was difficult to take in so much information and Wen’s tired eyes kept closing.

FOR TWO days and two nights, the train rocked its silent passengers along their journey. It was early morning when it pulled into the large city of Chengdu. Wen was relieved to have arrived, for here she would find the recently built road that joined China to Tibet for the last leg of her journey. She was eager to see the road. She remembered the news reports when it had opened in 1954, proclaiming what an extraordinary feat of engineering it was. Joining Chengdu with Lhasa, a distance of nearly 2,500 kilometers, it was the longest road in China and the first proper road in Tibet. The four years it had taken to construct the road seemed short considering the number of mountains it had to cross, fourteen in all, and the rivers too, at least ten. The terrible snows and freezing winds that the laborers had had to bear were legendary.

ALTHOUGH AUTUMN was fast approaching, Chengdu was still enveloped in the humid, stifling heat of summer. Getting down from the train, Wen wiped her face with the sleeve of her sweat-soaked uniform. She could not imagine how shamefully dirty her face must be. It felt sore-rubbed raw by the continual wiping away of sweat during the journey. A huge number of soldiers were crowded on the platform, but the station was oddly hushed. The sardine-can conditions and lack of oxygen had exhausted everyone. Wen searched along the neat line of army placards on the platform, looking for the unit number she needed.

Eventually she found a notice bearing the number 560809 held up by a soldier with a startlingly youthful face. She fished out from an inner pocket her now rather damp military papers and passed them to the hand attached to the face. The face smiled briefly and the hand beckoned. Two weeks of travel with the army had taught Shu Wen the body language of soldiers like this one. As she staggered in the wake of the childlike young man she considered how, as a student, she had never thought to wonder how China’s fifty-six groups and thousand regional accents managed to communicate when they got together. Now she realized the importance of gesture and the common language of human emotion.

Wen had imagined that once she reached Chengdu, she would be able to start making inquiries about Kejun right away, but when she joined Kejun’s former unit she discovered that only the number 560809 remained the same: the whole unit had been re-formed, from officers down to foot soldiers, and no one knew exactly where the previous unit had been fighting in Tibet, let alone about Kejun’s own particular section. A staff officer told her that, going by previous deployments, they might have been somewhere near the Bayan Har mountains in the unpopulated northeast region of Qinghai. However, information was scarce because there had been few survivors and those that there were had already been posted elsewhere. On the inside cover of her Collected Essays of Liang Shiqiu, Wen wrote down “Bayan Har mountains.” Perhaps she would be able to find more detailed information about Kejun on the way to this place-although her heart went cold at the thought that there were few survivors. “My Kejun is alive,” she recited to herself, over and over again.

There were two days of rest, reorganization, and instruction about going into Tibet. Wen and two other doctors were taught how to deal with some of the problems they would encounter, including altitude sickness. They were each given a portable oxygen tank and many spare cylinders. Goodness knows how I’m going to carry these around, thought Wen, if I begin to suffer from mountain sickness myself. Most of them had experienced a little altitude sickness already-a slight headache, a touch of breathlessness-but it was bound to get worse the farther they traveled into Tibet. The average altitude of “the roof of the world” was around 4,000 meters.

Finally Wen and her comrades-in-arms clambered into their army trucks and set off along the famous Sichuan-Tibet Highway. On their backs they carried their few possessions wrapped up in a quilt and bound onto a backpack with a cord. At night they would simply unroll their quilts and sleep on the ground.

The convoy was huge: several dozen trucks containing nearly a thousand men. Wen was overwhelmed by both the number of soldiers and the magnificence of the road. It was even more impressive than she had imagined. Endlessly twisting and turning, it took them through crowds of mountains. The weather was constantly evolving. One minute it was like a warm spring day with flowers in bloom, then suddenly white snow was flying around them. She felt as if she had entered a fairyland where a thousand years in the outside world passed in a single day.

Most of the soldiers on the trucks were young men of about twenty. They laughed noisily and punched each other as they discussed what little they knew of Tibet-the lamas, hermits, and nomads; the legendary cruelty of the people. Wen could tell that, beneath their bravado, they were nervous. They knew nothing of the conflict they were entering and rumors of the brutal physical punishments that Tibetans meted out to their enemies abounded. Wen realized that most of these young soldiers were uneducated peasants, utterly incapable of understanding such a diverse, remote people. She thought of Kejun’s dedication to his Tibetan studies, his determination to master the language. She squashed herself into a corner of the truck and meditated on her goal: to find Kejun. Her thoughts were like a cocoon and she barely noticed the chatter of the other soldiers, the intense discomfort of the journey, the freezing cold nights, the extraordinary landscape. She was roused from her reverie only when, after days of traveling along the highway, the convoy of vehicles left the road and began driving over grassland that seemed to stretch endlessly in all directions. Wen had no idea where they were headed. She didn’t even know if they were driving north or south. She wondered if they would be going anywhere near the Bayan Har mountains. She hadn’t been prepared for a landscape that lacked any kind of landmark around which to orient oneself. They hadn’t yet seen a single sign of human habitation.

The convoy was able to proceed only in stops and starts, and cases of altitude sickness began to increase. Some of the soldiers in the trucks cried out that their heads hurt, some couldn’t breathe properly, and some could hardly stand. As one of only three doctors in a convoy of more than a thousand soldiers, Wen had to rush back and forth with the portable oxygen tank on her back, teaching soldiers how to breathe, while feeding oxygen to those who were already semiconscious.

Just as people were beginning to acclimatize, Wen realized that something worse was happening. The convoy was slowing down and they could hear scattered gunfire in the distance. Sometimes they thought they saw human figures hiding behind rocks and thickets. They began to fear an ambush. Within a few days, the difficult terrain forced the convoy to split up and Wen’s truck was left in a group of only seven vehicles. Although the area they were traveling through had allegedly already been “liberated” by the Liberation Army, there was hardly a local to be seen, no military units, and no signals accessible to the radio operators. Anxiety began to eat away at the soldiers on board the trucks as the emptiness of the mountains, the thinness of the air, and the violent changes in the weather enfolded them in a world of fear.

During the daytime they derived some comfort from the extraordinary scenery and the living creatures they spotted along the way-the birds and animals. But at night, with the dramatic drop in temperature, the sounds of animals, and the moaning of the gales through the trees, Wen and her companions felt caught halfway between this world and the next. Nobody knew what was going to happen. They expected death to strike at any time. They huddled together around their campfires and tried desperately to sleep. Wen lay awake listening to the wind. She seemed to hear Kejun’s voice in the trees, warning her to be careful, not to get soaked by the dew or burned by the campfire, not to go off alone.

One morning, as the company woke at the light of dawn, the rigid corpses of two soldiers were discovered, gleaming Tibetan knives protruding from their breasts. The soldiers on sentry duty confirmed to each other in whispers that they hadn’t heard a single thing all night long. The knives must have been thrown with incredible precision.

The next day, and the day after that, exactly the same thing happened: no matter how many watchmen they stationed, or how many fires they lit, the weary soldiers were greeted at dawn by two corpses stabbed with Tibetan knives. There could be no further doubt: they were being hunted.

Nobody could understand why only two soldiers were being killed each time. Whoever was doing this had chosen not to attack the whole convoy but to play a more dangerous game. Because two of the dead were drivers and no one else knew how to drive, they were forced to abandon two of the trucks and crowd into the remaining vehicles. A deathly silence fell over the convoy. Wen knew that everyone was contemplating the sudden, violent fate that might become theirs.

Wen had no fear of death. She felt that she was drawing ever closer to Kejun. Sometimes she even hoped that she had entered the borderland between the living and the dead. If Kejun was already on the other side, she wanted to see him as soon as possible, no matter what manner of hellish underworld he was suffering in.

One afternoon, someone on one of the trucks pointed off into the distance, shouting, “Look-something moving!” True enough, in the direction he indicated, there was something rolling about on the ground. Wen saw one soldier about to shoot, but hurried to stop him. “If it was anything dangerous, it would have already attacked us, or run away,” she reasoned. The company commander, who was on Wen’s truck, overheard her. He ordered the truck to stop and dispatched a few soldiers to go and investigate. Soon they returned carrying the thing on their backs: it was an unimaginably filthy Tibetan, of indeterminate gender, covered all over with bright and jangling jewelry.

3 ZHUOMA

Wen gently cleaned away the grime to reveal a face with a warm, terra-cotta-colored complexion and sun-scorched rosy cheeks. It was a typical Tibetan woman’s face, Wen realized-dark almond-shaped expressive eyes, a sensual mouth with a full lower and thin upper lip, and a straight, broad nose. But its youthful features seemed to have been ravaged by some terrible ordeal or illness-the eyes were bloodshot and listless, and from the sore and blistered mouth, the woman could only utter an exhausted slur of indecipherable sounds. She couldn’t possibly have been involved in the recent night killings-a thought that had crossed Wen’s mind-because she was barely alive.

A soldier passed Wen a flask of water, and she poured its contents, drop by drop, into the woman’s mouth. Her thirst quenched, the woman muttered two words in Chinese: thank you.

“She can speak Chinese!” a soldier yelled out to the assembled crowd of onlookers.

Everyone was very excited: this was the nearest to a Tibetan they’d ever been, and she spoke Chinese too. Immediately they all began to wonder whether she’d be able to help them prevent any more attacks, maybe by offering protection of some kind. Wen spotted the company commander glancing over in her direction as he conferred with officers from the other trucks. She supposed they must be discussing what to do with the Tibetan woman.

The commander walked over to Wen. “What’s the matter with her? Will she be any use to us?”

Wen realized that the woman’s life was in her hands. After taking the woman’s pulse and using her stethoscope to listen carefully to her heart and chest, she turned back to the commander.

“I’d say she’s just suffering from extreme exhaustion-she’ll soon recover.”

It happened to be the truth, but Wen knew she would have said the same thing even if it weren’t. She didn’t want to see the Tibetan woman abandoned.

“Get her onto the truck, then let’s go.” The commander climbed back on board without another word.

Once on the road, the Tibetan woman fell into a dazed sleep and Wen explained to her fellow soldiers that she probably hadn’t eaten, drunk, or even slept for several days and nights. She could see that the soldiers didn’t really believe her, but still everyone squeezed up to give the Tibetan woman as much space as possible.

Wen stared in fascination at the woman’s necklaces and amulets rising and falling with her labored breathing. Her heavy gown, though coarse and covered with dust and dirt, was in places finely embroidered. This was no peasant woman, Wen thought. And then she smiled to herself as she suddenly realized that every soldier in the truck, some open-mouthed, couldn’t take their eyes off this exotic creature.

WEN THOUGHT that day would never end. The road became increasingly rough and broken up as they slowly made their way through several precarious mountain passes. The wind gained so much strength that it rocked the trucks from side to side. At last they set up camp for the night in the shelter of a jutting rock. The commander suggested putting the woman close to one of the campfires-first, to give her the warmth she still needed but, more important, to deter the killers who had probably continued to follow them. They all settled down to a very uneasy sleep.

In the middle of the night, Wen heard the Tibetan woman give out a low moan. She sat up.

“What is it? Do you need something?”

“Water… water.” The woman’s voice sounded desperately weak.

Wen gave her some water as quickly as she could, then a generous portion of flour paste from the supplies. Earlier in the day, when they had first found the woman, Wen had only managed to give her a very small amount of food from her own rations, but now that they had set up camp and the provisions had been unpacked, she managed to put aside some more. Gradually the woman began to come back to life and was able to speak.

“Thank you,” she said. “You are very kind.” Although the woman spoke Chinese clearly, her accent was strange.

“I’m a doctor,” said Wen, searching her mind for the Tibetan word for “doctor,” which Kejun had once told her. “Menba. I can take care of you. Don’t talk. Wait until you feel better. You’re still very ill.”

“There’s nothing seriously wrong with me, I’m just exhausted. I can talk.” With great effort, the woman shifted her limp body closer to Wen.

“No, stay there, I can hear you. What is your name?”

“Zhuoma,” the woman said weakly.

“And where is your home?”

“Nowhere. My home is gone.” The woman’s eyes filled with tears.

Wen was utterly at a loss for words. After a brief silence, she asked, “Why can you speak such good Chinese?”

“I learned Chinese as a child. I have visited Beijing and Shanghai.”

Wen was amazed. “I come from Suzhou,” she said, excitedly, desperately hoping that the woman would know her hometown. But in an instant, Zhuoma’s face was animated and full of anger.

“Then why have you left it to come and kill Tibetans?”

Wen was about to protest when suddenly the woman cried out in Tibetan. The men, who were already on edge, leaped to their feet. But it was too late: yet another soldier was dead, stabbed through the heart with a Tibetan knife. Shots and shouts rang out as a temporary madness descended over the soldiers. Then a terrifying quiet returned, as if a hideous fate were hanging over the first person to produce the tiniest sound.

Out of the silence, a soldier whipped around and pointed his gun at Zhuoma, who was still too weak to stand.

“I’ll shoot you dead, Tibetan! Shoot-you-dead!” he screamed. He made as if to pull the trigger.

With a courage she didn’t know she had, Wen threw herself between Zhuoma and the soldier.

“No, wait, she hasn’t killed anyone, you can’t murder her!” Her voice was trembling but firm.

“But it’s her people who are killing us. I-I don’t want to die!” The soldier looked as if he were about to explode with panic and fury.

“Kill her, kill her!” More and more soldiers joined in the argument. They were all on the side of the man with the gun.

Wen stared at the commander, hoping he’d come to her rescue, but his face remained stony.

“Good menba,” Zhuoma said, “let them kill me. There’s so much hatred between the Chinese and the Tibetans, no one can make things right again now. If killing me will bring them some sort of peace, I’m happy to die here.”

Wen turned to face the crowd. “You hear that? This woman would sacrifice herself to you. Yes, she is Tibetan, but she likes us, she likes our culture, she’s been to Beijing, to Shanghai. She can speak Chinese. She wants to help us. Why should we take her life just to make ourselves feel better? What would you think if people killed your loved ones for revenge? What would you do?” Wen was close to tears.

“The Tibetans have killed us for revenge,” one soldier blustered.

“They have reasons for resentment and so do we, but why must we make things worse and create new hatreds?” As soon as the words were out of Wen’s mouth, she thought how pointless it was talking to these uneducated soldiers who knew only love and hate. Wang Liang had been right: war drew clear lines of love and hate between people.

“What do women know about enemies? Or hate?” shouted a voice from the crowd. “Just shoot the Tibetan.”

Wen spun around to face the voice. “Who says I don’t know about enemies? Or hate? Do you know why I left Suzhou and traveled thousands of miles to this terrifying place? I came looking for my husband. We’d only been married three weeks when he went to war in Tibet and now he’s disappeared. My life is nothing without him.” Wen burst into tears.

The soldiers fell silent. Wen’s weeping was accompanied only by the rustling and popping of burning wood. Dawn was beginning to break and a little extra light was illuminating the camp.

“I know what it is to hate. If my husband is really dead, dead at the age of twenty-nine, I’m here for revenge, to find his murderers. But don’t you think the people here hate us too? Haven’t you wondered why we haven’t seen any people here? Don’t you think that perhaps it has something to do with us?”

Wen looked around at her silenced audience, and continued more slowly and deliberately.

“All this death over the last few days is a warning to us. I’ve been thinking about it a lot: I’m just as afraid, as full of hate as you are. But why are we here? Have the Tibetans welcomed us? We’ve come to liberate them, but why do they hate us?”

“Company, fall in!”

The commander interrupted Wen. As the soldiers got into line, the commander whispered to her, “I understand what you’re saying, but you can’t talk to the soldiers like that. We are a revolutionary army, not a force for oppression. Get into line and await orders.” The commander turned to the soldiers. “Comrades, we’ve found ourselves in a very complex and serious situation. We must remember the army’s Three Great Regulations and Eight Principles, and the Party’s policy on minorities. We forgive the misunderstandings of the Tibetan people, strive for their cooperation and understanding, and work as hard as we can for the liberation of Tibet.”

The commander glanced over to Zhuoma and Wen.

“If we want to liberate Tibet, we need the help of the Tibetan people, especially Tibetans who can speak Chinese. They can lead us out of danger, win over the locals, and resolve misunderstandings. They can help us find water and places to camp, and teach us about the culture and customs of the Tibetans. The leadership has decided to take Zhuoma on as our guide and interpreter.”

Everyone was stunned by this unexpected announcement, none more so than Zhuoma. Confusion was written all over her face. She plainly found it difficult to understand the commander’s heavy Shanxi accent or what he meant by the army’s regulations and principles, but she realized that the soldiers had stopped looking at her with such fierce hatred. With no further explanation, the commander dispatched soldiers to bury their dead comrade, light the stoves for breakfast, put out the campfire, and check over the weapons store. Yet again the murdered man had been a driver, and so another truck had to be abandoned. The remaining trucks were now more crowded than ever. Before the convoy set off, the commander arranged for Zhuoma and Wen to sit together in the cab of the truck, where he usually sat. He said it was to allow the soldiers “a bit more room,” but Wen knew he wanted to give her and Zhuoma an opportunity to rest safely.

For the first part of the journey Zhuoma drifted into a long sleep, her head on Wen’s shoulder. When she woke up, Wen was pleased to see that life had begun to return to her eyes. Wen made her eat a little more flour paste, and as Zhuoma’s cheeks regained some color, she saw how young and beautiful she was.

“Where is your family?” asked Wen. “Where were you going?”

Zhuoma’s eyes were filled with sadness. As the truck jolted along, she quietly told Wen the story of her life.

ZHUOMA WAS twenty-one. Her father had been the head of an important, landowning family in the Bam Co region, a fertile area just north of Lhasa that was one of the gateways through the mountains, providing access to the north of Tibet. He presided over a large household with extensive lands and many serfs. Zhuoma’s mother had died giving birth to her, and her father’s other two wives had not produced children, so she had been her father’s greatest treasure.

When she was five years old, two Chinese men in military uniforms had come to stay in their household. Her father said that they had come to research Tibetan culture. It was only later that Zhuoma learned that they had been envoys sent by the Nationalist government in China to research the arts and customs of Tibet. The two Chinese had taken a great shine to her and, in their halting Tibetan, had told her many fascinating stories. The older of the two had preferred stories to do with Chinese history. He had told her about how five thousand years ago Da Yu had stopped the Yellow River from flooding by dividing it into two branches; how Wang Zhaojun, one of the Four Beauties of Chinese history, had brought peace to the north of China by marrying a barbarian king; how the principles of political power were contained in a book called The Three Kingdoms; and how Sun Yat-sen had founded the modern state of China. The younger man had entranced her with Chinese legends and stories of female daring. He talked of Nu Wa and how she had held a stone up to a hole in the sky when she saw it was broken, the Monkey King, who had challenged the authority of the heavens, and the young girl Mulan who had disguised herself as a man and joined the army in the place of her father, remaining undetected for many years.

Zhuoma had been enthralled by these tales, which were utterly different from anything in Tibetan culture. She pestered the two men endlessly, until they began to tell everyone that Zhuoma asked more questions than there were stars in the sky. With their encouragement, she learned to read Chinese characters, although she hadn’t wanted to write them herself, intimidated by the difficulty of copying the many pictures. The men had returned to China the year Zhuoma turned fifteen, taking with them many scrolls in Tibetan and leaving behind for her a huge pile of books, as well as a great loneliness and yearning for China.

As she was growing up, she would constantly beg her father to let her visit China, but he always said no, arguing that she was too young, or that it wasn’t a convenient time. But when she heard her father telling people that he was planning to emulate other landowners and send her to study in England because of the historic links between the two countries, she threatened never to marry if he did not let her see Beijing. Her father relented and allowed her to accompany an estate owner from a neighboring region on a trip to China. Since she could speak Chinese, this man had agreed to take her along, on the condition that she obey the sacred Tibetan law not to speak about what she knew and not to ask about what she didn’t know.

And so the young Zhuoma went to Beijing in springtime.

“The people and the traffic terrified me,” Zhuoma told Wen. “I’d thought of Beijing as another great grassland, like Tibet, with a different language and culture, of course, but no more than that. It was a huge shock. I couldn’t believe how much the Chinese talked. Their faces seemed so white and clean, completely unmarked by life. There were no horses, no grass, no space, only buildings, cars, people, streets, and lots of noise. And Shanghai shocked me even more. I saw creatures with golden hair and blue eyes-like the ghosts you see in Tibetan paintings-just walking along the streets. Our Chinese companion explained that they were ‘Westerners,’ but I didn’t know what he meant and couldn’t ask because I had to keep my promise not to ask about ‘what I didn’t know.’”

When Zhuoma returned to Tibet, she was dying to tell people about all the strange and exciting things she had seen, but no one understood what she was talking about. Her father seemed to have something very serious on his mind. His permanent anxiety and gloom robbed him of all interest in what she had to tell him, while his two wives never talked to Zhuoma anyway. To compensate for his neglect, her father began to send his groom to keep her company and listen to her stories.

“My father couldn’t bear to see me so lonely, but all he could think of doing to help was to send me one of his servants. It never entered his mind that I might fall in love with the groom.”

A shadow of anguish passed across Zhuoma’s face.

“My father was furious when he found out. He told me that what I was experiencing was not love but simply need. All I knew was what I felt: that I wanted to be with this man all the time, and that I loved everything about him.

“In my area of Tibet,” Zhuoma continued, “love between a noble and a servant is forbidden. It is the will of the spirits, and there is nothing anyone can do to change that. But we are all creatures of emotion, and emotions are not so easily circumscribed. Because of this there are certain rules in place. If a male servant and a noblewoman fall in love, then the only option is for the man to take the woman far away. If he does this, she loses everything: family, property, even the right to exist in her native place.

My father knew I was stubborn so he took the advice of the family retainer, who had been his counselor since he was a child, and sent me back to Beijing with a group of servants.”

The man who had first taken Zhuoma to China had Chinese friends in Beijing and the seventeen-year-old Zhuoma went to stay with them. Soon afterward her servants were ordered home. They could not cope with their alien surroundings. To them Beijing seemed not to belong to the human world at all. They felt surrounded by demons. No one spoke their language or ate their food. Without temples or monasteries they were completely unprotected by the spirits. Zhuoma, on the other hand, thrived. She enrolled at the Central Institute of Nationalities-a university set up by the Communist government specially to educate young people from China’s minority territories. There the groom was soon replaced in her young mind by her love of Chinese culture.

“I loved meeting people so different from Tibetans,” Zhuoma confided to Wen. “I loved Beijing, with its huge Tiananmen Square. At the institute, my Chinese was already much more fluent than that of most of the other minority students and I progressed well in my studies. At home I had never traveled beyond the confines of my father’s land and I was excited to learn that the various regions of Tibet had many different customs and many branches to its one religion. When I graduated, I decided to stay on as a teacher and translator of Tibetan.

“But it was not to be. Just as I was in the process of moving from the students’ to the teachers’ dormitory, I received a message that my father was seriously ill.”

Zhuoma described how she had set out for Tibet that same evening, traveling as fast as she could day and night, first by train, then by horse and cart, and finally on horseback, whipping on the horse in her haste to return to her father’s lands. But when she arrived at the foot of the Tanggula mountains, servants, who had been waiting for her there, broke the news that their lord hadn’t been able to hold out for a last sight of his daughter. He had died seven days earlier.

Overwhelmed by grief and disbelief, Zhuoma made her way home. She could see in the distance the prayer flags fluttering from the hall where her father lay in state. When she came nearer she heard the chants of the lamas who would send her father’s spirit to heaven. Inside the hall, her father was already wrapped in a shroud, with his two wives kneeling silently to his left. On his right was a portrait of Zhuoma’s dead mother with the jade Buddha amulet she had used while alive. The gold-embroidered hassock Zhuoma used to pray on had been placed beneath the golden statue of the Buddha that sat at her father’s head. He was surrounded by offerings to the spirits, white khata prayer scarves, sacred inscriptions, and other objects brought as tributes by friends, relatives, and the household and farm serfs.

“I was my father’s heir,” Zhuoma explained. “As a young woman, I had never thought about my father’s duties as the head of such a large estate. Nor had he ever talked to me about such matters. But now, after the forty-nine days of burial rites had been observed, my father’s retainer took me aside and explained to me the heavy burdens that had been my father’s in the weeks before he died.

“He showed me three letters. One was from another local governor urging my father to support the Army of Defenders of the Faith and rise up against the Chinese. It said that the Chinese people were monsters and were bringing shame upon the lands of the Buddha. The letter told him to contribute silver, yaks, horses, cloth, and grain to the army and to poison the water sources to deprive the Chinese of sustenance.

“The second letter was from a Chinese general named Zhang who wanted my father to help ‘unite the motherland.’ He said that he hoped my father would help him to avoid bloodshed but that, if he did not, he would have no choice but to send soldiers onto his land. He told my father that I was being well cared for in Beijing.

“The third letter was from my father’s fourth brother. It had arrived just before my father died. My father’s brother advised him to flee west with his family, saying that in his region fierce fighting had broken out between Tibetans and Chinese. All the temples were destroyed, the landowners slaughtered, and the serfs fled. He had heard a rumor that I was being held captive in Beijing. He hoped his letter would arrive in time. He himself was awaiting his fate.

“On reading these letters I was thrown into confusion. I did not understand why there should be so much hatred between my homeland and my dreamland. I realized that my father’s death must have been caused by his great anxiety. He was caught between threats from both the Chinese and the Tibetans. He would not have been able to bear the scenes described in my uncle’s letter. Religion is the lifeblood of the Tibetan people.

“For hours I thought about what to do. I had no desire to help the Army of Defenders of the Faith kill Chinese people, nor did I want the blood of my own people to pollute the land. My property and my role as head of the estate meant little to me any longer. And so I decided to walk away from the fighting in the hope of finding freedom…”

Zhuoma went on to describe in a quiet voice how she had dismantled her estate. Having sent her stepmothers away with great piles of gold, she let the household servants go free and divided much of her property among them. The ornaments and jewels that had been in her family for generations she concealed in her clothing, hoping they would protect her and allow her to buy food in days to come. Then she opened the granaries and distributed their contents among the serfs. She sent the household’s precious golden Buddha and the other religious objects to a monastery. All the time she was conscious of being watched by her father’s retainer. He had been with the family since her father was three and had begun to learn the scriptures. Three generations of her family had benefited from his wisdom and resourcefulness. Now he was forced to witness the destruction of the household.

When all was done, Zhuoma walked through the house surveying its empty rooms. It was dusk and she carried a flaming torch. Before she left, she intended to burn the house down. As she was about to set the building alight, her retainer approached her, his head bent.

“Mistress,” he said. “Since in your heart, this house is already burned to ashes, will you leave it to me?”

Zhuoma was taken aback. It had never occurred to her that this servant would ask such a thing.

“But there is nothing here,” she stammered. “How will you live? The fighting is getting nearer…”

“I came here with empty hands and I will leave with empty hands,” said the man. “The spirits will direct me. Here I was received into the Buddhist faith. In life or death my roots are here. Mistress, please grant my request.”

All the time that he was speaking, he did not raise his head.

Zhuoma looked at him. She realized that this man was not the lowly servant of her childhood. His face was utterly changed.

“Very well,” she said, feeling the gravity of her words. “May the spirits protect you and bring you your desire. Raise your head and receive your home.”

With this, she passed him the torch.

Zhuoma led her horse to the gateway of the courtyard, counting each step as she went-599 in all. When she reached the gate, she turned around and, for the first time in her life, realized how imposing her childhood home was. The two-story decorated archway was resplendent with bright colors; the workshops, kitchens, servants’ quarters, stables, storehouses, and granaries to either side were beautifully maintained. Far off in the distance, her father’s retainer stood like a statue, illuminated by the torchlight.

She turned out of the gatehouse and in what was left of the daylight noticed a man and a horse, the horse heavily laden with baggage. “Who’s that?” she asked in surprise. “Mistress, it’s me,” came the reply. The voice was familiar.

“Groom? Is that you? What are you doing here?”

“I… I wanted to be a guide for my mistress.”

“A guide? How do you know where I want to go?”

“I know. I knew it when my mistress came back from Beijing and told me stories.”

ZHUOMA WAS so moved she didn’t know what to say. She had never thought the groom was a man of such feeling and passion. She wanted to see his expression, but he spoke with a lowered head.

“Raise your head and let me look at you,” she said.

“Mistress, your groom does not dare…”

“From now on, I am no longer your mistress and you are no longer my groom. What is your name?”

“I have no name. I am simply ‘Groom,’ like my father.”

“Then I will give you a name. May I?”

“Thank you, Mistress.”

“And you must call me Zhuoma, or else I will not have you as my guide.”

“Yes… no,” the man mumbled in confusion.

ZHUOMA SMILED as she told Wen how she had named the groom Tiananmen after the great square that had so impressed her in Beijing. But her expression soon turned to sadness as she described what had followed.

As she and Tiananmen were preparing to ride away from the house, Tiananmen suddenly pointed to the sky and cried out.

“Mistress, a fire! A great fire!”

Zhuoma turned to see her house ablaze and, in the courtyard, her family retainer howling prayers as he burned. The tears ran down her face. Her family’s loyal servant was immolating himself in the house to which he had sacrificed his life.

Wen held her breath as she imagined what it must be like to lose one’s family like that. As Zhuoma continued with her story, she was barely able to hold back the tears.

Zhuoma and Tiananmen had traveled east, toward China. Tiananmen was a good guide, taking them away from the usual routes and avoiding the conflict between the Chinese and the Tibetans. They had plenty of food-dried meat, barley, some butter and cheese. The rivers gave them water, and there was wood for the fire. Although they had to cross several high mountain passes, Tiananmen always knew where they could seek shelter. During the long journey, Tiananmen put his heart and soul into looking after Zhuoma: finding water, preparing food, collecting firewood, laying out the bedding, keeping watch at night. He overlooked nothing. Zhuoma had never before lived out in the open and didn’t know how to help him. As she sat beside the leaping campfire or jolted along on her horse, she drank in his silent love. Despite their desperate situation, she felt hope and happiness. But then the weather changed. A great wind came over the steppe, bringing with it a blizzard that rolled up into itself anything it found before it. The horses were struggling badly, and Zhuoma and Tiananmen could only inch forward. Realizing it was too dangerous to continue, Tiananmen laid out a place for the exhausted Zhuoma to sleep in the lee of a huge boulder. He then positioned himself in the path of the gale to shelter her.

In the middle of the night, Zhuoma was awoken by the howling of the wind. She shouted for Tiananmen but there was no answer. She struggled to stand up but could not keep her footing in the gale, and instead crawled about searching and shouting. Lost in the pitch darkness, she lacked any landmark by which to orient herself. Finally she fainted and fell over a mountain edge into a rocky ravine.

When she came around from her stupor, the sky had been washed bright blue. Zhuoma was lying on the stony slopes of a gully. There was no sign of Tiananmen, his belongings, or any of their luggage. The blue heavens watched in silence as she wept; several vultures soared over her head, echoing her cries with their own.

“I shouted Tiananmen’s name over and over again until my throat was hoarse,” Zhuoma said. “I had no idea what to do next. Fortunately, I was unhurt, but I didn’t know where I was or which way to go. I am the daughter of a nobleman: I am used to being looked after by servants. All I knew about east and west was the rising and setting of the sun. I walked for days without meeting a single person. Then I collapsed with cold and hunger. Just as I thought I was going to die, I heard your trucks and I prayed to the Lord Buddha that you would see me.”

THERE WAS a long silence in the cab of the truck. Wen didn’t know how to speak to Zhuoma after all she had heard. In the end it was the driver of the truck who spoke first. Although he had appeared to be concentrating on the difficult road, he had heard every word.

“Do you think Tiananmen is still alive?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” replied Zhuoma. “But if he is, I will marry him.”

THAT EVENING, everyone was afraid to sleep. Around the campfires, the exhausted soldiers sat back to back, with one group of men facing toward the fire, the other keeping watch over the darkness. Every hour they swapped places.

As they sat there, Wen remembered something. She turned to Zhuoma.

“When we were attacked this morning, you shouted something in Tibetan. What did it mean? How did you know the Tibetans had come?”

“I heard them whispering the ritual words that Tibetans utter as a signal to kill. I wanted to tell them not to do it, that there was a Tibetan in the group…”

Wen was about to ask more when Zhuoma cried out again, a piercing, desolate shriek that made everyone’s hair stand on end.

As the cry died away, the people in the outer circle could see black shadows moving toward them.

Instinct told Wen that no one should move, that anyone who moved would be dead. Within a few seconds, countless Tibetans armed with guns and knives had surrounded them. Wen thought the end had come. Then a sorrowful song floated up into the air. The tune was Tibetan but the words were Chinese:

Snowy mountain, why do you not weep? Is

your heart too cold?

Snowy mountain, why do you weep? Is your

heart too sore?

Everyone watched Zhuoma as, continuing to sing, she slowly stood up and walked over to the leader of the Tibetans. Having first performed a Tibetan greeting, she drew an ornament from her gown and presented it to him. The sight of the ornament had an immediate effect on the Tibetan. He gestured to his men, who all took a step back. He then returned Zhuoma’s greeting and started speaking to her in Tibetan.

Wen and the rest of the company had no idea what was being said, but they were sure Zhuoma was trying to work out a way to save them. After many tense minutes, Zhuoma returned. The Tibetans, she said, wished to punish them. On its way westward, the People’s Liberation Army had extinguished the eternal flames in the monasteries and killed many of their herdsman. The Tibetans believed that 231 herdsman had been lost and they intended to take double that number of Chinese lives in compensation. Though Zhuoma had tried to negotiate with them, they refused to be merciful, arguing that to release the Chinese would allow them to kill more Tibetans. However, the Tibetan leader had said he would give them a chance if they agreed to three conditions. First, the Tibetans wanted to take ten Chinese as hostages, to be killed if the Liberation Army killed any more of their people; second, they wished the Chinese to return to their lands in the east and never to take another step westward again; third, the Chinese must leave behind all their weapons and equipment, including their trucks.

The radio operator argued that having to walk back with no food or water was no different from dying. Zhuoma told him that the Tibetans were prepared to leave them some dried meat.

All this time, the company commander had been very silent. Now he asked Zhuoma to return to the Tibetans and request permission for him to hold a meeting with his men. It was not long before Zhuoma came back. “They agree,” she said. “You are to put your weapons on the ground and stand over there.”

The commander unbuckled his gun belt, gently laid it on the ground, then turned to address his men.

“All Party members put their weapons on the ground as I have, and then follow me over there for a meeting. The rest remain here.”

Twenty or thirty soldiers left the silent crowd, watched by the Tibetans. Several minutes later, some of the men returned to the ranks but twelve remained by the commander. The commander asked Zhuoma to tell the Tibetans that, although they had requested ten hostages, twelve Party members wished to live and die together. They would therefore provide an additional two hostages. Clearly moved by the self-sacrifice of the two extra hostages, the Tibetans gave the departing Chinese not only the promised meat, but a few waterskins and knives.

The two women remained behind with the Tibetans. Wen had told Zhuoma something of her search for Kejun and her desire to head north toward Qinghai. Through Zhuoma’s influence, the leader of the Tibetans had agreed to let them accompany his men westward. When the time came for the women to go north, he would give them a guide. As Wen sat behind Zhuoma on one of the Tibetans’ horses, clinging to her waist for dear life, she asked how Zhuoma had managed to negotiate with the Tibetans. Zhuoma explained that her ornaments identified her as the head of an estate. Although Tibetans were divided into many different groups, each with its own culture and customs, they all made sacrifices to Buddha, and all leaders had identical ornaments, which were a symbol of their power. The leader of the Tibetans had immediately recognized her superior status. She was glad to have been able to use her power to help Wen, because she owed the Chinese menba her life.

The group journeyed west for four and a half days. The leader then came to Zhuoma and Wen and told them that if they still wished to go to Qinghai, it was here that they should head north. They had just stopped to pack food and water for the women when three messengers on horseback came flying toward them reporting that the Chinese cavalry was up ahead. The Tibetan leader immediately ordered his men to hide their horses in the undergrowth nearby and Zhuoma guided their horse to follow.

In the thicket, Wen could not help being excited at having come across Chinese forces so unexpectedly. Perhaps Kejun would be among them. Her elation was soon quelled by the fury on the faces of the Tibetans, and the sight of the twelve Chinese hostages being led into a mountain pass. Terrified, she watched as a large unit of Chinese cavalry pursued and killed the few Tibetans who had not hidden themselves quickly enough. Gunfire was all around. Men fell from their horses, spouting blood. Wen grasped Zhuoma’s hand, trembling at the gruesome scene. The Tibetan woman’s hand was clenched.