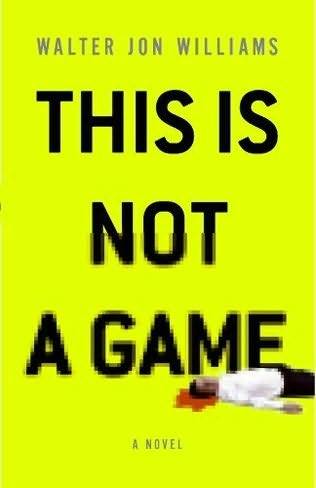

THIS IS NOT A GAME is a novel built around the coolest phenomenon in the world.

That phenomenon is known as the Alternate Reality Game, or ARG. It's big, and it's getting bigger. It's immersive and massively interactive, and it's spreading through the Internet at the speed of light.

To the player, the Alternate Reality Game has no boundaries. You can be standing in a parking lot, or a shopping center. A pay phone near you will ring, and on the other end will be someone demanding information.

You'd better have the information handy.

ARGs combine video, text adventure, radio plays, audio, animation, improvisational theater, graphics, and story into an immersive experience.

Now, one of science fiction's most acclaimed writers, Walter Jon Williams, brings this extraordinary phenomenon to life in a pulse-pounding thriller. This is not a game. This is a novel that will blow your mind.

Walter Jon Williams

This Is Not a Game

(с) 2008

What if the game called you?

– Elan Lee

ACT 1

CHAPTER ONE This Is Not a Mastermind

Plush dolls of Pinky and the Brain overhung Charlie’s monitor, their bottoms fixed in place with Velcro tabs, toes dangling over the video screen. Pinky’s face was set in an expression of befuddled surprise, and the Brain looked out at the world with red-rimmed, calculating eyes.

“What are we going to do tonight, Brain?” Charlie asked.

Pickups caught his words; software analyzed and recognized his speech; and the big plasma screen winked on. The Brain’s jutting, intent face took on a sinister, underlit cast.

“What we do every night, Pinky,” said the computer in the Brain’s voice.

Welcome, Charlie, to your lair.

Hydraulics hissed as Charlie dropped into his chair. Ice rang as he dropped his glass of Mexican Coke into the cup holder. He touched the screen with his finger, paged through menus, and checked his email.

Dagmar hadn’t sent him her resignation, or a message that gibbered with insanity, so that was good. The previous day she had hosted a game in Bangalore, the game that had been broadcast on live feed to ten or twelve million people, a wild success.

The Bangalore thing had turned out wicked cool.

Wicked cool was what Charlie lived for.

He sipped his Coke as he looked at more email, dictated brief replies, and confirmed a meeting for the next day. Then he minimized his email program.

“Turtle Farm,” he said. The reference was to a facility on Grand Cayman Island, where he kept one of his bank accounts. The two words were unlikely to be uttered accidentally in combination, and therefore served not only as a cue to the software but as a kind of password.

A secure screen popped up. Charlie leaned forward and typed in his password by hand-for the crucial stuff, he preferred as little software interface as possible-and then reached for his Coke as his account balance came up on the screen.

Four point three billion dollars.

Charlie’s heart gave a sideways lurch in his chest. He was suddenly aware of the whisper of the ventilation duct, the sound of a semitruck on the highway outside the office building, the texture of the fine leather upholstery against his bare forearm.

He looked at the number again, counting the zeros.

Four point three billion.

He stared at the screen and spoke aloud into the silence.

“This,” he said, “must stop.”

CHAPTER TWO This Is Not a Vacation

Dagmar lay on her bed in the dark hotel room in Jakarta and listened to the sound of gunfire. She hoped the guns were firing tear gas and not something more deadly.

She wondered if she should take shelter, lie between the wall and the bed so that the mattress would suck up any bullets coming through the big glass window. She thought about this but did not move.

It didn’t seem worthwhile, somehow.

She was no longer interested in hiding from just any damn bullet.

The air-conditioning was off and the tropical Indonesian heat had infiltrated the room. Dagmar lay naked on sheets that were soaked with her sweat. She thought about cool drinks, but the gunfire was a distraction.

Her nerves gave a leap as the telephone on the nightstand rang. She reached for it, picked up the handset, and said, “This is Dagmar.”

“Are you afraid?” said the woman on the telephone.

“What?” Dagmar said. Dread clutched at her heart. She sat up suddenly.

“Are you afraid?” the woman said. “It’s all right to be afraid.”

In the past few days, Dagmar had seen death and riots and a pillar of fire that marked what had been a neighborhood. She was trapped in her hotel in a city that was under siege, and she had no friends here and no resources that mattered.

Are you afraid?

A ridiculous question.

She had come to Jakarta from Bengaluru, the city known formerly as Bangalore, and had been cared for on her Garuda Indonesia flight by beautiful, willowy attendants who looked as if they’d just stepped off the ramp from the Miss Indonesia contest. The flight had circled Jakarta for three hours before receiving permission to land, long enough for Dagmar to miss her connecting flight to Bali. The lovely attendants, by way of compensation, kept the Bombay and tonics coming.

The plane landed and Dagmar stood in line with the others, waiting to pass customs. The customs agents seemed morose and distracted. Dagmar waited several minutes in line while her particular agent engaged in a vigorous, angry conversation on his cell phone. When Dagmar approached his booth, he stamped her passport without looking at it or her and waved her on.

She found that there were two kinds of people in Soekarno-Hatta International Airport, the frantic and the sullen. The first talked to one another, or into their cell phones, in loud, indignant-sounding Javanese or Sundanese. The second type sat in dejected silence, sometimes in plastic airport seats, sometimes squatting on their carry-on baggage. The television monitors told her that her connection to Bali had departed more than an hour before she’d arrived.

Tugging her carry-on behind her on its strap, Dagmar threaded her way between irate businessmen and dour families with peevish children. A lot of the women wore headscarves or the white Islamic headdress. She went to the currency exchange to get some local currency, and found it closed. The exchange rates posted listed something like 110,000 rupiah to the dollar. Most of the shops and restaurants were also closed, even the duty-free and the chain stores in the large attached mall, where she wandered looking for a place to change her rupees for rupiah. The bank she found was closed. The ATM was out of order. The papers at the newsagent’s had screaming banner headlines and pictures of politicians looking bewildered.

She passed through a transparent plastic security wall and into the main concourse to change her ticket for Bali. The Garuda Indonesia ticket seller didn’t look like Miss Jakarta. She was a small, squat woman with long, flawless crimson nails on her nicotine-stained fingers, and she told Dagmar there were no more flights to Bali that night.

“Flight cancel,” the woman said.

“How about another airline?” Dagmar asked.

“All flight cancel.”

Dagmar stared at her. “All the airlines?”

The woman looked at her from eyes of obsidian.

“All cancel.”

“How about tomorrow?”

“I check.”

The squat woman turned to her keyboard, her fingers held straight and flat in the way used by women with long nails. Dagmar was booked on a flight leaving the next day at 1:23 P.M. The squat woman handed her a new set of tickets.

“You come two hour early. Other terminal, not here.”

“Okay. Thanks.”

There was a tourist information booth, but people were packed around it ten deep.

All cancel. She wondered how many had gotten stranded.

Dagmar took out her handheld. It was a marvelous piece of technology, custom-built by a firm in Burbank to her needs and specifications. It embraced most technological standards used in North America, Asia, and Europe and had a satellite uplink for sites with no coverage or freaky mobile standards. It had SMS for text messaging and email, packet switching for access to the Internet, and MMS for sending and receiving photos and video. It had a built-in camera and camcorder, acted as a personal organizer and PDA, supported instant messaging, played and downloaded music, and supported Bluetooth. It could be used as a wireless modem for her PC, had a GPS feature, and would scan both text and Semacodes.

Dagmar loved it so much she was tempted to give it a name but never had.

She stepped out of the terminal, and tropical heat slapped her in the face. Mist rose in little wisps from the wet pavement, and the air smelled of diesel exhaust and clove cigarettes. Dagmar saw the Sheraton and the Aspac glowing on the horizon, found their numbers online, and called. They were full. She googled a list of Jakarta hotels, found a five-star place called the Royal Jakarta, and booked a room at a not-quite-extortionate rate.

Dagmar found a row of blue taxis and approached the first. The driver had a lined face, a bristly little mustache, and a black pitji cap on his head. He turned down his radio and gave her a skeptical look.

“I have no rupiah,” she said. “Can you take dollars?”

A smile flashed, revealing brown, irregular teeth.

“I take dollar!” he said brightly.

“Twenty dollars,” she said, “to take me to the Royal Jakarta.”

“Twenty dollar, okay!” His level of cheerfulness increased by an order of magnitude. He jumped out of the cab, loaded her luggage into the trunk, and opened the door for her.

Above the windshield were pictures of movie stars and pop singers. The driver hopped back in the car, lit a cigarette, and pulled into traffic. He didn’t turn on the meter, but he turned up the radio, and the cab boomed with the sound of Javanese rap music. He looked at Dagmar in the rearview mirror and gave a craggy-toothed smile.

Then the terror began.

None of the drivers paid any attention to lanes. Sometimes the taxi was one of five cars charging in line abreast down a two-lane road. Or it would weave out into oncoming traffic, accelerating toward a wall of oncoming metal until it darted into relative safety at the last possible instant.

Automobiles shared the roadway with trucks, with buses, with vans and minibuses, with bicycles, with motorbikes, and with other motorbikes converted to cabs, with little metal shelters built on the back. All moved at the same time or were piled up in vast traffic jams where nothing moved except for the little motorbikes weaving between the stalled vehicles. Occasional fierce rain squalls hammered the window glass. The driver rarely bothered to turn on the wipers.

What Dagmar could see of the driver’s face was expressionless, even as he punched the accelerator to race toward the steel wall of a huge diesel-spewing Volvo semitruck speeding toward them. Occasionally, whatever seeds or spices were in the driver’s cigarette would pop or crackle or explode, sending out little puffs of ash. When this happened, the driver brushed the ashes off his chest before they set his shirt on fire.

Dagmar was speechless with fear. Her fingers clutched the door’s armrest. Her legs ached with the tension of stomping an imaginary brake pedal. When the traffic all stopped dead, which it did frequently, she could hear her heart hammering louder than the Javanese rap.

Then the cab darted out of traffic and beneath a hotel portico, and a huge, gray-bearded Sikh doorman in a turban and an elaborate brocade-spangled coat stepped forward to open her door.

“Welcome, miss,” he said.

She paid the driver and tipped him a couple of bucks from her stash of dollars, then stepped into the air-conditioned lobby. Her sweat-soaked shirt clung to her back. She checked into the hotel and was pleased to discover that her room had Western plumbing, a bidet, and a minibar. She showered, changed into clothes that didn’t smell of terror, and then went to the hotel restaurant and had bami goreng along with a Biltong beer.

There was a string quartet playing Haydn in a lounge area off the hotel lobby, and she settled into a seat to listen and drink a cup of coffee. American hotels, she thought, could do with more string quartets.

A plasma screen was perched high in the corner, its sound off, and she glanced up at CNN and read the English headlines scrolling across the bottom of the screen.

Indonesian crisis, she read. Government blamed for currency collapse.

She could taste a metallic warning on her tongue.

All cancel, she thought.

Dagmar had been in Bengaluru for a wedding, but not a real wedding, because the bride and groom and the other principals were actors. The wedding was the climax of a worldwide interactive media event that had occupied Dagmar for six months, and tens of thousands of participants for the past eight weeks.

Unlike the wedding, Bengaluru was real. The white-painted elephant on which the groom had arrived was real. The Sikh guards looking after the bride’s borrowed jewelry were real.

And so were the eighteen-hundred-odd gamers who had shown up for the event.

Dagmar’s job was to create online games for a worldwide audience. Not games for the PC or the Xbox that gamers played at home, and not the kind of games where online players entered a fantasy world in order to have adventures, then left that world and went about their lives.

Dagmar’s games weren’t entertainments from which the players could so easily walk away. The games pursued you. If you joined one of Dagmar’s games, you’d start getting urgent phone calls from fictional characters. Coded messages would appear in your in-box. Criminals or aliens or members of the Resistance might ask you to conceal a package. Sometimes you’d be sent away from your computer to carry out a mission in the world of reality, to meet with other gamers and solve puzzles that would alter the fate of the world.

The type of games that Dagmar produced were called alternate reality games, or ARGs. They showed the players a shadow world lurking somehow behind the real one, a world where the engines of existence were powered by plots and conspiracies, codes and passwords and secret errands.

Dagmar’s job description reflected the byzantine nature of the games. Her business card said “Executive Producer,” but what the players called her was puppetmaster.

The game that climaxed in Bengaluru was called Curse of the Golden Nagi and was created for the sole purpose of publicizing the Chandra Mobile Communications Platform, a fancy cell phone of Indian manufacture that was just breaking into the world market. Live events, where gamers met to solve puzzles and perform tasks, had taken place in North America, in Europe, and in Asia, and all had climaxed with the fictional bride and the fictional groom, having survived conspiracy and assassination attempts, being married beneath a canopy stretched out in the green, flower-strewn courtyard of one of Bengaluru’s five-star hotels and being sent to their happily-ever-after.

Dagmar’s own happily-ever-after, though, had developed a hitch.

The hotel room was good. Dagmar spent a lot of time in hotel rooms and this was at the top of its class. Air-conditioning, exemplary plumbing, a comfortable mattress, a complimentary bath-robe, Internet access, and a minibar.

The rupiah had collapsed, but Dagmar had $180 in cash, credit cards, a bank card, and a ticket out of town. Indonesia was probably going to go through a terrible time, but Dagmar seemed insulated from all that.

She’d passed through too many time zones in the past four days, and her body clock was hopelessly out of sync. She was either asleep or very awake, and right now she was very awake, so she propped herself with pillows atop her bed, made herself a gin and tonic with supplies from the minibar, and called Charlie, her boss. It was Monday morning in the U.S.-in fact it was yesterday, on the other side of the date line, and Charlie was going through a day that, to Dagmar, had already passed its sell-by date.

“How is Bangalore?” he asked.

“I’m not in Bangalore,” she told him. “I’m in Jakarta. I’m on my way to Bali.”

It took a couple of seconds for Charlie’s surprise to bounce up to a satellite and then down to Southeast Asia.

“I thought you were going to spend two weeks in India,” he said.

“Turns out,” Dagmar said, “that Siyed is married.”

Again Charlie’s reaction bounced to the Clarke Orbit and back.

“I’m so sorry,” he said.

“His wife flew from London to be with him. I don’t think that was his original plan, but I have to say he handled the surprise with aplomb.”

Her name was Manjari. She had a polished Home Counties accent, a degree from the London School of Economics, beautiful eyes, and a lithe, graceful, compact body in a maroon silk sari that exposed her cheerleader abdomen.

She was perfect. Dagmar felt like a shaggy-haired Neanderthal by comparison. She couldn’t imagine why Siyed was cheating on his wife.

Except for the obvious reason, of course, which was that he was a lying bastard.

“Serves me right,” Dagmar said, “for getting involved with an actor.”

The actor who had played the male ingenue in Curse of the Golden Nagi, in fact. Who was charming and good-looking and spoke with a cheeky East London accent, and who wore lifts in his shoes because he was, in fact, quite tiny.

Leaving for another country had seemed the obvious solution.

“Anyway,” she said, “maybe I’ll find some cute Aussie guy in Bali.”

“Good luck with that.”

“You sound skeptical.”

An indistinct anxiety entered Charlie’s tone. “I don’t know how much luck anybody can have in Indonesia. You know the currency collapsed today, right?”

“Yeah. But I’ve got credit cards, some dollars, and a ticket out of town.”

Charlie gave it a moment’s thought.

“You’ll probably be all right,” he said. “But if there’s any trouble, I want you to contact me.”

“I will,” Dagmar said.

Dagmar had the feeling that most employees of multimillionaire bosses-even youthful ones-did not quite have the easy relationship that she shared with Charlie. But she’d known him since before he was a multimillionaire, since he was a sophomore in college. She’d seen him hunched over a console in computer lab, squinting into Advanced D &D manuals, and loping around the Caltech campus in a faded Hawaiian shirt, stained Dockers, and flip-flops.

It was difficult to conjure, in retrospect, the deference that Charlie’s millions demanded. Nor, to his credit, did Charlie demand it.

“If it’s any consolation,” Charlie said, “I’ve been looking online, and Golden Nagi looks like a huge hit.”

Dagmar relaxed against her pillows and sipped her drink.

“It was The Maltese Falcon,” she said, “with a bit of The Sign of Four thrown in.”

“The players didn’t know that, though.”

“No. They didn’t.”

Being able to take credit for the recycled plots of great writers was one of her job’s benefits. Over the past few years she’d adapted Romeo and Juliet, The Winter’s Tale, The Comedy of Errors (with clones), The Libation Bearers, The Master and Margarita (with aliens), King Solomon’s Mines, and It’s a Wonderful Life (with zombies).

She proudly considered that having the zombies called into being by the Lionel Barrymore character was a perfect example of a metaphor being literalized.

“When you revealed that the Rani was in fact the Nagi,” Charlie said, “the players collectively pissed their pants.”

“I’d rather they creamed their jeans.”

“That, too. Anyway,” Charlie said, “I’ve got your next job set up for when you get back.”

“I don’t want to think about it.”

“I want you thinking about it,” said Charlie. “When you’re on the beach in Bali looking some Aussie guy in the glutes, I want you distracted by exciting new plots buzzing through your brain.”

“Oh yeah, Charlie,” sipping, “I’m going to have all sorts of plots going through my mind, you bet.”

“Have you ever heard of Planet Nine?”

“Nope.”

“A massively multiplayer online role-playing game that burned through their funding in the development stage. They were just about to do the beta release when their bank foreclosed on them and found that all they’d repossessed was a lease on an office and a bunch of software they didn’t have a clue about.”

Dagmar was surprised. “They were getting their start-up funding from a bank? Not a venture capital outfit?”

“A bank very interested in exploiting the new rules allowing them to invest in such things.”

“Serves them right,” Dagmar judged.

“Them and the bank.” Cheerfully. “So I heard from Austin they were looking for a sugar daddy, and I bought the company from the bank for eleven point three cents on the dollar. I’ve rehired the original team minus the fuckups who caused all the problems, and beta testing’s going to begin in the next few days.”

Alarms clattered in Dagmar’s head. “You’re not going to want me to write for them, are you?”

“God, no,” Charlie said. “They’ve got a head writer who’s good-Tom Suzuki, if you know him-and he’s putting his own team in place.”

Dagmar relaxed. She already had the perfect game-writing job; she didn’t want something less exciting.

She sipped her drink. “So what’s the plan?”

“Planet Nine is going to launch in October. I want an ARG to generate publicity.”

“Ah.” Dagmar gazed with satisfaction into her future. “So you’re going to be your own client.”

“That’s right.”

Charlie had done this once before, when work for Great Big Idea had been scarce. He’d paid his game company to create some buzz for his software company-buzz that hadn’t precisely been necessary, since the software end of Charlie’s business was doing very well on its own. But Dagmar had been able to build a plot around Charlie’s latest generation of autonomous software agents, and she’d been able to keep her team employed, so the entire adventure had been satisfactory.

This time, however, there were plenty of paying customers sniffing around, so Charlie must really want Planet Nine to fly.

“So what’s this Planet Nine again?” she asked.

“It’s an alternate history RPG,” Charlie said. “It’s sort of a Flash Gordon slash Skylark of Space 1930s, where Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto on schedule, only it turned out to be an Earthlike planet full of humanoids.”

“Out beyond Neptune? The humanoids would be under tons of methane ice.”

“Volcanoes and smog and radium projectors are keeping the place warm, apparently.”

Dagmar grinned. “Uh-huh.”

“So along with the folks on Planet Nine, there are dinosaurs and Neolithic people on Venus, and a decadent civilization sitting around the canals on Mars, and on Earth you’ve got both biplanes and streamlined Frank R. Paul spaceships with lots of portholes. So Hitler is going into space in what look like big zeppelins with swastikas on the fins, and he’s in a race with the British and French and the Japanese and the New Deal, and there’s plenty of adventure for everybody.”

“Sounds like a pretty crowded solar system.”

“There’s a reason these people went broke creating it.”

Dagmar took a lingering sip of her drink. She’d always had an idea that writing space opera would be fun, but had never steered her talent in that particular direction.

The writers of ARGs were almost always drawn from the ranks of disappointed science fiction writers. It was odd that there hadn’t been more space opera from the beginning.

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll think about it. But not while I’m nursing an umbrella drink and watching the Aussie guys at the beach.”

Charlie sighed audibly. “All right, you’re allowed to have some good dirty fun on your vacation. But not too much, mind you.”

“Right.”

“And here’s something else to think about. I’m giving you twice the budget you had for Golden Nagi.”

Dagmar felt her own jaw drop. She looked at the carbonation rising in her glass and put the glass down on the plastic table.

“What are you telling me?” she said.

“I’m telling you,” said Charlie, “that the sky’s the limit on this one. If you tell me you need to send a camera crew off to Planet Nine to take pictures, then I’ll seriously consider it.”

“I-” Dagmar began.

“Consider it a present for doing such a good job these past few years,” Charlie said. She could sense Charlie’s smile on the other end of the phone.

“Think of it,” he said, “as a vacation that never ends.”

Hanseatic says: I was so totally floored when it was revealed that the Rani had really been the Nagi all along.

Hippolyte says: Ye flippin gods! SHE was an IT!

Chatsworth Osborne Jr. says: I was expecting this. The players’ guide turning out to be the villain has been a trope ever since Bard’s Tale II.

Hippolyte says: The Rani isn’t the villain!

Chatsworth Osborne Jr. says: Of course she is. Who put the curse on all those people, I ask you?

“We heard a rumor that the airlines can’t afford to buy jet fuel any longer,” the Dutch woman said the next morning. “Not if they’re paying in rupiah.”

Dagmar considered this. “The foreign airlines should be all right,” she said. “They can pay in hard currency.”

The Dutch woman seemed dubious. “We’ll see,” she said.

The Dutch woman-horse-faced and blue-eyed, like a twenty-first-century Eleanor Roosevelt-was half of an elderly couple from Nijmegen who came to Indonesia every year on vacation and had been due to leave the previous evening on a flight that had been canceled. They and Dagmar were waiting for the office of the hotel concierge to open, the Dutch couple to rebook, and Dagmar to confirm her own tickets. A line of the lost and stranded formed behind them: Japanese, Javanese, Europeans, Americans, Chinese, all hoping to do nothing more than get out of town.

Dagmar had checked news reports that morning and found that the government had frozen all bank accounts to prevent capital flight and had limited the amount of money anyone could withdraw over the course of a single day to something like fifty dollars in American money.

A government spokesman suggested the crash was the fault of Chinese speculators. The governments in other Asian countries were nervous and were bolstering their own currencies.

The concierge arrived twenty minutes late. The shiny brass name tag on his neat blue suit gave his name as Mr. Tong. He looked a youthful forty, and Dagmar could see that the cast of his features was somehow different from that of the majority of people Dagmar had met in Indonesia. She realized he was Chinese.

“I’m very sorry,” Tong said as he keyed open his office. “The manager called a special meeting.”

It took Mr. Tong half an hour to fail to solve the problems of the Dutch couple. Dagmar stepped into the glass-walled office and took a seat. She gave Mr. Tong her tickets and asked if he could confirm her reservations with the airline.

“I’m afraid not.” His English featured broad Australian vowels. “The last word was that the military has seized both airports.”

She hesitated for a moment.

“How can people leave?” she asked.

“I’m afraid they can’t.” He took on a confidential look. “I hear that the generals are trying to prevent the government from fleeing the country. There’s a rumor that the head of the Bank of Indonesia was arrested at the airport with a suitcase full of gold bars.”

“Ferries? Trains?”

“I’ve been through all that with the couple who were here ahead of you. Everything’s closed down.”

And where would I take a train anyway? Dagmar wondered.

Mr. Tong took her name and room number and promised to let her know if anything changed. Dagmar walked to the front desk and told them she’d be staying another night, then tried to work out what to do next.

Have breakfast, she thought.

The dry monsoon had driven out the rain clouds of the previous day, and the sky was a deep, cloudless tropical blue. Dagmar had breakfast on the third-floor terrace and sat beneath a broad umbrella to gaze out at the surrounding office towers and tall hotels, all glowing in the brilliant tropical sun. Other towers were under construction, each silhouette topped by a crane. A swimming pool sat in blue splendor just beyond the terrace. It was about as perfect as a day in the tropics could be.

Her fruit platter arrived, brought by a very starched and correct waiter, and Dagmar immersed herself in the wonder of it. She recognized lychee and jackfruit, but everything else was new. The thing that looked like an orange tasted unlike any orange she’d ever had. Everything else was wonderful and fresh and splendid. The croissant that accompanied the platter-a perfectly acceptable croissant in any other circumstances-was bland and stale by comparison. The meal was almost enough to make Dagmar forget she was stuck in a foreign city that she’d never intended to visit and that had just fallen into economic ruin as surely as if all the great, glittering buildings around her had crumbled into dust.

What happened to you, she wondered as she looked up at the steel-and-glass buildings around her, when your money was suddenly worthless? How could you buy food, or fuel for your car? How could anyone pay you for your labor?

No wonder her taxi driver had been so happy to get American money. With dollars he could feed his family.

On her journey she had taken two hundred dollars with her in cash, for use in emergencies. With that money, she realized, she was better off than all but a handful of the twenty-five million people living in Jakarta.

After finishing her coffee, she decided that since she was stuck in Jakarta, she might as well enjoy the place as much as she could. She returned to her room to change clothes. She put on a cotton skirt and a long-sleeved silk shirt she’d brought with her from the States, an outfit she hoped would be suitable for a Muslim country.

She considered buying clothes here, but all she had was the $180. The dollars, she thought, she should definitely save for emergencies.

She left a hundred of the dollars tucked into her luggage and put the rest, along with her remaining Indian rupees, in a fanny pack. Then she put a hat on her head-a panama, with a black ribbon, that had been woven by machine of some new plastic version of straw. She could roll it up into a tube and stuff it in her luggage-which you could do with a genuine straw panama as well, but this at one-tenth the price.

It set off her gray hair very nicely. Her hair had started going gray when she was seventeen, and by the time she entered college the last of her dark brown hair had turned. She hadn’t minded much at the time-the look had been eye-catching, especially since her eyebrows had remained dark for an interesting contrast, and when she got tired of it, the gray hair was easy to dye a whole rainbow of colors. Eventually she’d grown fond of the gray and decided not to color it any longer. It was a decision that, now that she’d just passed thirty, she was comfortable with, though she reserved the right to change her mind as her biological age caught up with the age of her hair.

It amused her that some people, in an effort to be kind, called her an ash blond.

A younger version of the previous night’s Sikh doorman let her out of the hotel and offered to summon a cab. She said that she’d walk, and he wished her a good morning.

As she set off down the street, she wondered if there was some kind of Brotherhood of Sikh Doormen that had somehow monopolized jobs in many of the big Asian hotels. Perhaps, she thought, that could be an element in some future game-Sikh doormen in various Asian cities would all be part of some conspiracy, and players would have to try to cadge information from them.

No, she thought. Too elaborate. And auditioning Sikh doormen to find out which of them could act would be a time-consuming process.

The dry monsoon had failed to blow away the equatorial heat, and the sun was fierce, but tall trees had been planted on either side of the road to provide shade. She used a flyover to cross four lanes of Jakarta’s insane traffic. The air had the fried-fritter smell of biodiesel mixed with the scent of hot asphalt.

The area was dominated by office towers and hotels, but there were smaller buildings in between with shops and eateries. Billboards and neon signs advertised Yamaha bikes, Anker Bir, and Chandra handsets, the appearance of which made Dagmar smile. Celebrities endorsed beauty products and whiskeys. Street food was available-Dagmar imagined the vendors had to sell their seafood and meats before they spoiled. The smaller shops were open-the single owner, or members of his family, looked out at the street, face impassive-but the medium-size stores, the ones that couldn’t make their payroll in the current situation, were closed. Even in the shade the heat was appalling, so Dagmar stepped into a building that had been converted into a kind of vertical shopping mall, and wandered around in cool air for a while. The international chains, Bok-Bok Toys and Van Cleef and Arpels, were open; the smaller, locally owned businesses, the camera and clothing stores, were closed. There seemed to be few customers in any case, and the goods available for purchase weren’t anything Dagmar couldn’t get at home.

She paused for a moment at an indoor skating rink, a few young people in tropical clothing making lazy circles to the sounds of 1970s American pop.

Back to the heat and the traffic. She made a random turn onto a boulevard shaded by rows of cone-shaped trees, where a series of blocky old office buildings stood with their window air conditioners humming. There was a lot of green in Jakarta-trees, bushes, tropical ferns, and more palms than in L.A. She made another turn and found herself heading toward some kind of square or park-or maybe just a big, empty parking lot. Dagmar saw the open area was filled with people, and that many of them were carrying angry-looking signs and banners; she made a U-turn just as a pair of police vans turned down the street, each filled with men in blue uniforms and white helmets and crossbelts.

Dagmar increased her pace, not about to get between the police and a bunch of pissed-off citizens.

A few blocks away, music boomed out over the street, louder than the traffic. The sound came from a music and video store. The music thundering from its speakers was propulsive: layers of Indian tabla; a harmony line drawn by a chiming synthesizer, a metallic sound influenced by the gamelan; and on top of it all a bubbly 1950s-style pop vocal. Dagmar was completely charmed.

She stepped into the narrow store. Local films glowed from plasma screens, all heroic action, men with bare, blood-spattered torsos, headbands, and krises. The walls were covered with movie posters and pictures of pop stars. There was a row of terminals where customers could download music into portable storage, for transfer into whatever media later suited them.

The fact that this store existed at all told her that most Indonesians still made do with dial-up, assuming that they had Internet at all.

A young man with a Frankie Avalon haircut sat behind a counter up front. Dagmar gave him a nod, and he nodded back, an expression of surprise on his face. Clearly he didn’t see a lot of tourists in here.

Beneath the glass counter were interchangeable plastic cartridges of fuel for miniturbines and a lot of cheap memory storage, sticks and slabs and buttons with pop culture symbols: peace signs, the faces of pop stars and anime characters, popular heroes like Bruce Lee, Che Guevara, and Osama bin Laden, and of course the ubiquitous Playboy rabbit.

It’s a sad world, Dagmar thought, when you have to choose between Osama and Hugh Hefner.

Dagmar was the only customer. She went to one of the terminals where a pair of headphones waited. She took off her faux panama, stashed it atop the monitor, and put on headphones that smelled faintly of someone else’s sweat. The instructions were in Javanese, but she managed to call up a directory and began to sample what was on offer.

There was rap. There was reggae. There was heavy metal and bubblegum pop and classic rock and sappy love songs with far too much reverb. World culture was available to anyone with a T1 connection, and the local people downloaded it, wrung it for meaning, remixed it, rebranded it, uploaded it, and broadcast it onto the street from speakers mounted on the facades of music stores, from off-brand MP3 players, from speakers in taxi cabs, from podcasts and webcasts and radio and audio streamed from thousands of sources, from unlicensed radio stations run by enthusiastic amateurs in Brazilian favelas, by religious fanatics in Sumatran kampungs, by fierce college girls in Kansas with piercings in their navels and anarchy in their hearts…

And by Dagmar, standing atop the massive bandwidth of Great Big Idea Productions in Los Angeles, the media capital of the world. Dagmar, whose job was to take all that culture and history and find, or invent, the collusions and cabals that kept the world dancing… all the content zooming out into the world, where it would join with all the rest and be downloaded and adored and hated and absorbed and remixed again, only now with Dagmar’s fingerprints on it…

Now Dagmar, listening, was worried about how she was going to pay for any content that she downloaded. She figured that the kid behind the counter had no way of breaking one of her twenty-dollar bills, and she still had no local money, not that it would buy much. There was no sign saying the place took credit cards.

She went to the counter and tried talking to the kid, but despite all the rap and classic rock his store had on offer, he had no English at all. She offered credit cards, but he shook his head. She took out Indian rupees and waved them. He looked at them in a businesslike way and took a thousand-rupee note, about twenty dollars U.S., then waved her back to her station.

Dagmar was happy with the exchange, and she congratulated herself that the kid’s family would eat for the next couple of weeks. She took out her cell phone, thumbed the catch that revealed the USB connector, and plugged the phone into her terminal. She began her first download.

There was a few seconds’ pause, and then the phone screen began blinking red warnings at her, and an urgent pip-pip-pip began to sound. She looked at the screen for a startled instant, then yanked the phone from the connector. She reversed the screen to read it and discovered that the download store had just tried to load a virus into her handset.

She looked up at the kid with the Frankie Avalon haircut.

“You little bastard!” she said.

The kid affected nonchalance. What’s your problem, Kafir?

“You tried to steal my shit!” She turned off the phone, with any luck killing the virus, and marched to the counter. She banged the counter with the metal USB connector.

“Give me my rupees back!”

The kid shrugged. The rupees were nowhere in sight.

Dagmar had just about had enough of Jakarta.

“You want me to call the cops?” She looked out the door and to her immense surprise saw three policemen, right on the spot and right on time.

Two policemen, blue shirts and white helmets, rode a motorcycle. The driver kept the bike weaving between the cars stalled in traffic, and his cohort rode pillion, turning to look rearward as he talked into a portable radio.

The third policeman was on foot. He’d lost his white helmet, and blood ran freely from a cut on his forehead.

He was running like hell.

Dagmar became aware of a strange sound echoing up the street: bonk-whonk-thump-bonk! Like people kicking a whole series of metal garbage cans down the street, or the world’s biggest gamelan orchestra on the march. Behind the metal crashings there was a background noise, a roaring like the crowd in a stadium.

The kid was startled. He ran to the door and took a peek outside, and then suddenly there was a wide-eyed look of fear on his face and he was out on the stoop, reaching over his head to yank at the rolling mesh screen that covered the front of his shop when he wasn’t in it. He had forgotten Dagmar’s existence.

Bang-thump-whonk-thud! The metallic crashings were coming close.

The kid got the screen only about a third of the way down before a silver saucer sailed through the air, hit him squarely in the back of the head, and felled him like a tree. He dropped at Dagmar’s feet, unconscious. Dagmar looked in complete surprise at the VW hub-cap spinning in triumph on the pavement outside the store.

“Hey!” she said, to no one in particular.

And then the streets were full of running figures, scores and then hundreds of Indonesian men. Some carried sticks, some carried signs, and a few carried what looked like machetes.

The demonstration that she had seen in the public square a short while ago had become a riot.

The source of the metallic clanging sounds became apparent. The runners were banging on the hoods, roofs, and sides of the cars as they ran past them. Banging with their sticks or their fists. The trapped drivers stared at them in horror as they streamed past.

There were shrieks as a windshield caved in.

At the sound of the breaking glass, a wave of adrenaline seemed to pick Dagmar right up off the floor. The unconscious boy’s legs stretched out into the street, and she couldn’t lower the screen with him in the way. She knelt by him, hooked both hands in his arm-pits, and dragged him clear.

Then she looked up to see one of the rioters bent to enter the store. He was a small man with a goatee, a bare chest, and a cloth headdress. He carried a knife as long as his forearm.

He looked just like one of the men in the store’s heroic action vids.

Dagmar gave a yell, which startled the rioter. He drew back, then got a better look at Dagmar and took another step toward her.

Dagmar yelled again, jumped to her feet, and ran for the back of the store. She found a toilet cabinet and slammed the door shut and shot the little bolt. The cabinet was a little over three feet deep, with a discolored, streaked hole in the ground, a tank of water, and a battered green plastic scoop. Dagmar looked for an exit and saw a screened window too high to reach. She then looked for a weapon and saw a mop and bucket. The mop was too long to use in the confined space, so Dagmar snatched up the plastic scoop and held it like an ice pick as she faced the flimsy door and its flimsy lock.

In the store were a series of crashes and thuds. The music out front stopped playing. More crashes. Footsteps. Then silence.

Dagmar stayed braced behind the toilet door, scoop raised, ready to gouge whatever flesh she could out of an attacker. The air in the tiny room was hot and rank, and sweat dripped from Dagmar’s chin, patting down onto her silk shirt. Through the open window overhead she could hear, faintly, the poink-whong-bang of the rioters hitting the cars on the street.

But no sounds any closer than that.

She thought about calling for help on her cell but had no idea what number to call, and rather doubted she’d ever reach anyone who could help her. Even if she reached someone, she had no idea where in the city she was or what the street address of the store was.

Dagmar stayed in the toilet for another fifteen minutes, until the sounds of the riot had faded completely. Then-scoop poised to stab any intruder-she flicked the little bolt open and slowly pushed open the door.

Nothing happened.

Carefully she leaned out of the cabinet to scan the store. She could see almost the entire room. The kid still lay on his face near the front door. Several of the plasma screens had been smashed, and others carried away. Brilliant sunlight shone through the narrow windows and the open door.

Dagmar crept out of the cabinet and approached the front. What she could see of the street was empty: the cars and trucks had dispersed. No human beings were visible. The kid on the floor was still breathing and had bled freely from a cut on his scalp, though it looked as if the bleeding had stopped. The mesh screen was still partly deployed.

She stepped over the boy, looked left and right-smashed windows, broken bicycles, a Honda burning, sending up greasy black smoke-and then grabbed the screen and hung her weight on it. The screen rattled down, making a shocking amount of noise, and then hit bottom with a bang.

The bang echoed up and down the empty street.

Dagmar had no way of locking the screen, but hoped any rioters wouldn’t look too closely.

She retreated from the door, bent over the Indonesian kid, and tried to find a pulse in his neck. The heartbeat was strong: it looked as if the boy weren’t about to die anytime soon.

She saw a corner of her thousand-rupee note peeking out of the kid’s back pocket. She reached for it, then hesitated. Then withdrew her hand.

The boy had just had his store wrecked. A thousand rupees might keep him alive for the next few weeks.

She noticed her faux panama on the floor. Someone had stepped on it. She picked up the hat, brushed away the bits of broken glass that clung to it, and put it on her head.

She moved back into the store and waited for whatever was going to happen next.

CHAPTER THREE This Is Not a Cowboy

“Don,” said Austin to his speakerphone, “I think what we should do is follow the strategic plan.”

Austin listened with half his attention as Don protested this idea. He and his partners were spending a fortune to retrofit an old office building, and they didn’t even own it.

“What we need,” said Don, “is a building of our own.”

Pneumatics gave a gentle sigh as Austin leaned back in his office chair and put his feet up on his desk. He had been through this so many times before.

“Don,” he said, “we have a big performance benchmark coming up. We don’t have time to build you a new headquarters.”

“About that benchmark. I’ve got some ideas for new implementations -”

“No, Don,” said Austin. “Follow the business plan.”

“Just listen,” urged Don. “This is great.”

He explained his new ideas at length. Austin let his gaze drift to the window. Century City sat in the middle distance below, white modernist perfection above L.A.’s cap of smog. He thought about Jackson Hole and the sight of snowcapped mountains and the smell of pine, and for a moment he wished he were anywhere but here, going through this scenario yet one more time.

“That’s all good,” Austin said when Don paused for breath, “but we can save all that for Release 2.0. Right now we need to follow the strategic plan.”

“But wait!” Don said. “This will make it so much better. It’ll be really cool.”

And on and on, for another five minutes or so.

Austin listened vaguely to the speakerphone and thought about trout fishing. He thought about high mountain streams and wild-flowers and cowgirls in faded Levi’s and flannel shirts and straw cowboy hats.

On reflection, he changed the fantasy to girls in chaps and fringed vests and hats and nothing else.

Don went on and on.

This, Austin thought, was the problem with geniuses. They got bored too easily.

And most business was boring. You set goals and you worked hard to meet those goals and then you started working on the next set of goals. It was all too plodding for creative types, who came up with half a dozen new ideas every single day and wanted to bring them all into being instantly.

Don paused to take another breath.

“Listen,” Austin said. “What’s your job title again?”

Don paused as his mind shifted tracks.

“I’m chief technology officer,” he said.

“Right,” said Austin. “And what’s my job?”

“I don’t know what your title is.” Don’s voice was suspicious.

“Never mind my title,” said Austin. “What’s my job?”

“You’re VC,” said Don.

“Right,” said Austin. “I’m venture capital. Which means that I and my associates have invested in dozens of start-ups. Hundreds by now. And that means that we’ve seen a lot of strategic plans, successful and unsuccessful. And so what I am telling you now is that you need to follow the plan to which we all agreed.”

He congratulated himself on his sweet reasonableness, that and the excellence of his grammar, avoiding the dangling preposition even in speech.

“I can talk to my partners about the changes,” Don said. “And they’ll be okay with it.”

“Ask yourself,” Austin said, “if they’ll be okay with finding another source of start-up money after I refuse to give you any further capital.”

“But we agreed…”

Austin’s reply was lazy, airy, while he thought of cowgirls.

“Why do I have to follow the agreement, Don, when you don’t? ”

While Don, with greater intensity, explained his ideas all over again, Austin thought of cowgirls riding in slow motion through fields of daisies.

“Don,” Austin finally interrupted, “if you follow the business plan and achieve every benchmark and every deadline, and the firm establishes itself in its market niche, and the IPO happens and everyone leaves rich, you can buy all the buildings you want. And hang around and make all the new implementations that strike your fancy. No one will argue with you-you’ll be rich.”

“But-”

“So for now you need to follow the strategic plan. And if you don’t”-Austin smiled at the thought-“I will join your partners in voting you off the board, and you’ll get nothing. And please don’t think I can’t do it, because I can. Ask Gene Kring.”

There was a moment of puzzlement.

“Who’s Gene Kring?” Don asked.

“Exactly my point,” Austin said.

Honest to Christ, he thought, this guy was almost as bad as BJ.

CHAPTER FOUR This Is Not a Rescue

In midafternoon Dagmar heard tramping outside and peered out to see a double line of police marching down the street in line abreast, followed by police cars and vans. The police were dressed more seriously this time, in khaki, with long batons, shotguns configured to fire tear gas grenades, transparent shields marked POLISI, and round helmets that looked as if they were designed by samurai, with plates hanging down to cover the ears and back of the neck.

The kid with the Frankie Avalon hair was awake by then, if still unwell. He slouched against the wall beneath one of the shelves. His eyes weren’t very focused yet, but he didn’t seem about to drop dead.

Dagmar saw as the police passed that they were heading in the general direction of her hotel. She figured this was about as safe as her day was going to get.

She went to the door and rolled the screen up to waist height, then ducked down beneath the screen and out into the street. The rotating lights on the vehicles flashed on broken windows. Dagmar followed the police line down the street.

At the next intersection the police paused for directions, and that’s when someone noticed her. One of the cops in a car saw her, blipped the horn, and gestured her over. She bent toward him, and-talking around the cigarette in the corner of his mouth-he asked her a question in Javanese.

“Royal Jakarta Hotel?” she said hopefully.

The cop looked at her for a long, searching moment, then motioned her to stay where she was. He thumbed on his radio mic, spoke briefly with someone Dagmar assumed was a superior, and then turned back to Dagmar and spoke to her while gesturing at the rear door.

It seemed he wanted her to get in his car.

“There’s a man back there,” she said, pointing, “who’s hurt.”

He squinted at her and pointed at the rear door again.

She pointed at the download store. “Ambulance?” she said.

“No ambulance.” The cop was losing patience.

Dagmar thought she should insist on an ambulance. Instead she got in the backseat and hoped this wasn’t her last moment of freedom.

The car smelled strongly of the driver’s harsh tobacco. The driver put the car in gear and it sprang away, turning onto a side street. They were still heading in the general direction of the Royal Jakarta, which was encouraging.

A second cop riding shotgun turned around and grinned at her. He seemed very young.

“How are you?” he asked.

Dagmar looked at him in surprise.

“I’m all right,” she said. And then, because he seemed to expect a response, she asked, “How are you?”

“I’m good.” He made a fist and pumped it in the air. “I’m very good.”

The car swayed as it swerved around a truck that had been driven onto the curb and then looted. The young policeman nodded, then said, “Where are you going?”

“I’m going to Bali,” she said.

He pumped his fist again. “Bali’s very good.” He opened the fist and patted himself on the chest.

“I’m from Seringapatam.”

Dagmar thought about all the places she was from, and decided to mention the most recent.

“I’m from Los Angeles.”

“Los Angeles is very good! Very famous!” The cop was enthusiastic.

She glanced down a side street as they sped along, and gasped. A large building was on fire-she thought it might have been the shopping center she’d visited. Tongues of flame extruded from smashed windows to lick at the sides of the building. Fire trucks and police were parked outside, and she saw pieces of furniture in the streets where they’d been dropped-looted, apparently.

She thought she glimpsed bodies lying among the abandoned furniture, and then the car sped on.

“Are you in the movies?” asked the young cop.

Dagmar tried to get her mind back on the track of the conversation. Was she in the movies? she wondered.

The right answer was sort of, but that led to too much exposition. And she had a feeling that reality had taken enough turns today without her having to explain about alternate reality gaming.

“I write computer games,” she said.

“Computer games! Excellent!” The cop made a gun with his two hands and made machine-gun sounds. “Felony Maximum IV!” he said. “I always take the MAC-10.”

Dagmar had never played Felony Maximum, but it seemed wise to agree.

“The MAC-10 is good,” she said.

The car took another turn, and there, visible through the windshield, was the shining monolith of the Royal Jakarta Hotel. The car rocketed under the portico, and the driver stomped on the brakes, bringing the vehicle to a juddering halt.

“Thank you!” Dagmar said. “Thank you very much!”

She tried to open the door and found it wouldn’t open from the inside. The driver barked some impatient commands at the Sikh doorman-the same one who had been on duty in the morning-and then the doorman opened the car door and she stepped out.

“Thank you!” she said to the driver, who ignored her and sped away.

The Sikh was holding the hotel door for her. She looked up and down the facade of the hotel and saw broken windows. Hotel workers had already cleaned up the glass. A hundred yards farther down the street was an overturned minibus that had been set on fire. Greasy smoke hung in the brilliant tropical air.

No bodies, at least. A small favor, this.

Dagmar walked into the hotel, nodded to the doorman’s “Good afternoon, miss,” and went to Mr. Tong’s office. Mr. Tong was alone-apparently he’d already discouraged everyone who needed discouraging-and he looked up as she knocked on the doorframe.

“Miss Shaw?” he said. “Nothing’s changed, I’m afraid.”

“There’s a man,” Dagmar said, “who needs an ambulance.”

Together they got a map of the area, and Dagmar reconstructed her morning walk and the location of the music store. Mr. Tong made the call, then looked up at Dagmar.

“I’ve told them,” he said. “But I don’t know if they’ll come.”

Dagmar thanked Mr. Tong and left, trying to think if there was anything else she could do. Short of going back out onto the streets, there was nothing.

She went to her room and took off her sweat-stained clothing and stood in the shower for a long while. Then she lay naked on her sweet-smelling sheets and turned on a news program and heard the reporter from Star TV talk about “anti-Chinese rioting.”

Anti-Chinese? she wondered. From what she could see, the rioters hadn’t much seemed to care whose stuff they were looting.

The reporter went on to talk about an “unconfirmed number of deaths,” and the report was accompanied by video, mostly from cell phones, that had captured bits of the action.

CNN showed no video of the riot but broadcast a lengthy discussion of the causes of the currency collapse.

“The government went on a spending spree before the last election,” said the Confident Analyst. “It won them reelection, but they ran through almost all their foreign currency reserves just at the moment when the price of oil went soft. Then they made matters worse by keeping their current account deficit a state secret-and when that secret leaked, it was all over.”

All cancel, Dagmar thought.

CHAPTER FIVE This Is Not a Hiding Place

Start with a woman in a hotel room, Dagmar thought. Because there’s nowhere else to go, because all her options are gone. Because a stranger’s voice on the phone has told her to stay in this place until she’s told to go somewhere else.

From there, reaching back in time, her story unfolds. Perhaps in reverse order. That would be a nifty trick.

Except that you have to find the story. It’s not all in one place, as it would be in a novel or a movie. It’s scattered out all through the world, and most of it’s in electronic form.

That’s the sort of story Dagmar writes.

At the beginning of the sort of game that Dagmar designs for a living, you go down the rabbit hole. That’s what it’s actually called, “rabbit hole.” The rabbit hole draws you into a Looking-Glass Land-okay, Dagmar knows, she’s mixing the two Alice stories-a Looking-Glass Land where the truth lies, and where, unlike in real life, you can look behind the mirrors to find out what it is.

A rabbit hole could be anything. A jar of honey that appeared in the mail, a data stick found in a washroom, an online poker site. A wedding in Bengaluru, a ticket to Jakarta. A virus loaded onto your phone.

And where the rabbit hole took you was a place that was just like your own place, except there was another reality hidden there.

In Looking-Glass Land the truth was hidden in source code, layered into Photoshop, transmitted in Morse, hidden in music files, whispered in Swedish or Shanghainese or Yiddish. Secrets were revealed in table talk on poker sites, found in genealogical charts, written with spray enamel on the sides of buildings.

Dagmar figures that some of the woman’s backstory has to be found in Planet Nine. Or on Planet Nine. Because that’s where this thing has to start.

From: Dagmar

Subject: Indonesia Fubar

Charlie, I never made it to Bali. I’m stuck in the Royal Jakarta Hotel. There’s rioting all around and people are getting killed. The airports are closed and I can’t get out. I’ve got $180 in hard currency and some credit cards that I can’t use because the banks are all shut down.

I’ve called the embassy and they put my name on a list. They say that if the situation warrants, they will stage an evacuation. They also say in the meantime I might as well stay here, because it’s as safe as anyplace.

Any suggestions? You or Austin wouldn’t happen to know anyone out here with a helicopter, would you?

Elevator music-saccharine Indonesian pop-tinkled from speakers in the breakfast room. A lavish buffet had been set up for hotel guests: coffee, tea, fruit juices, and a bewildering amount of food, both Indonesian and Western.

Meals were no longer served on the third-floor terrace. Hotel management had apparently decided it was safer to keep their guests under cover.

“Did you see the pillar of smoke?” asked Mrs. Tippel.

“Yes.”

Dagmar hadn’t been able to miss it: her windows faced northwest, and from the fourteenth floor she had an excellent view of the part of the city that was on fire.

“That’s Glodok,” the Dutch woman said. “It’s where the Chinese people live.”

The elevator music tinkled on.

“In the sixties,” said her husband, “the Chinese were killed because they were Communists. In ’ninety-eight they were killed because they were capitalists. Now they’re being killed for capitalism again.”

“Scapegoats,” said Mrs. Tippel.

“Yes, yes.” Mr. Tippel’s blue eyes were sad. “The government or the military always need to blame others for their mistakes. And now the Chinese will pay for all the mistakes that the government made before the election.”

“And even if there were Chinese traders who attacked the rupiah,” said Mrs. Tippel, “they weren’t here in Indonesia. They were in Hong Kong or Shanghai or somewhere.”

The elderly Dutch couple had seen Dagmar wandering through the breakfast room with her fruit plate and invited her to join them.

Dagmar tasted a piece of fruit from her plate and paused for a moment to savor the astonishing bright taste. Then Mr. Tippel began to talk, and Dagmar lost interest in breakfast.

“In ’ninety-eight it was terrible,” said Mr. Tippel. “The military had just lost power, and they thought that if there was enough chaos, they would be called back. So the riots were actually led by the military.”

“There were rape squads,” said Mrs. Tippel.

Dagmar opened her mouth, closed it, strove for a response.

“Is that what’s happening now?” she asked.

The Tippels looked at each other.

“Who knows?” said Mr. Tippel. “The army’s up to something, though. They have the city under siege.”

All those games she’d played, Dagmar thought as the elevator music tinkled in the background. All those dungeon crawls and conflicts and mysteries, all those battles, skirmishes, raids, and sieges. All those rolls of a twenty-sided die, all those experience points.

And none of them worth a damn. She had no idea how to behave in a city being blockaded by its own military. She hadn’t known what to do in the face of a mob other than to lock herself in a toilet.

As far as action in the real world was concerned, all those games had been a complete waste of time.

When her ring tone went off-the first few bars of “Harlem Nocturne,” the Johnny Otis version-Dagmar didn’t notice right away. The sounds blended too well with Indonesian elevator music. And then she realized someone was calling her, and she snatched at the phone.

“Dagmar?” said Charlie. “Are you still in Jakarta?”

Dagmar’s heart gave a foolish leap at the sound of his voice. “Yes!” she said. “Yes, I’m still here.”

“Okay. I’ll arrange to get you out, then.”

“Good! Good!” Dagmar realized she was babbling and made an effort to achieve rational communication.

“How are you going to manage it?” she asked. “Because the embassy-”

“I’ve been with the Planet Nine people all day and only just got your email,” Charlie said. “But I already know enough to realize that the embassy’s fucked. They can’t evacuate you because all our military assets are tied up in the current Persian Gulf crisis, and my guess is that our government is too proud to ask anyone else to do it.”

That sounded like Uncle Sam all right, Dagmar thought.

“So,” she said, “what next?”

“Lucky for you I’m a multimillionaire,” Charlie said. “I’m going to get in touch with some security firms, and we’re going to stage our own private evacuation. If necessary, we’ll fly you off the hotel roof in a helicopter.”

Dagmar paused a moment to picture this.

“Big box office,” she said.

“Does your handheld have a GPS feature?”

“Yes.”

“Give me your coordinates, then.”

As the Tippels watched with interest, Dagmar thumbed a button, and her coordinates flashed onto the phone’s screen.

“Six degrees eleven minutes thirty-one point eight seconds south, a hundred six degrees forty-nine minutes nineteen point four eight seconds east.”

“Got it,” he said. “I’ll give them your coordinates and phone number and email, and we’ll see what they can arrange.”

“Good,” Dagmar said, and then she added, “Thanks, Charlie.”

“No problem.”

“You keep saving me,” she said.

“I haven’t saved you yet,” he said. “And if I’m going to, I’d better hang up and contact the troops.”

“I love you, Charlie,” Dagmar said with sudden urgency.

There was a moment of silence as Charlie dealt with his surprise.

“I’m fond of you, too,” he said. “Whatever you do, don’t leave the hotel.”

“No problem there.”

“Take care. Someone will call soon.”

“Thanks!” But Charlie had hung up.

Dagmar reluctantly closed the phone and returned it to her belt.

“Your boyfriend?” asked Mrs. Tippel.

Dagmar shook her head. “My boss.”

Mrs. Tippel seemed a little surprised.

“He must be a good employer,” she said.

He’s hiring mercenaries to rescue me, Dagmar almost said. But she reflected that so far as she knew, no mercenaries were coming for the Tippels or for anyone else in the breakfast room, and that to mention her good fortune might seem tactless, as if she were boasting about her return to the life of a privileged Westerner.

“We went to college together,” she said.

Hiring mercenaries, she thought.

It was like something you’d do in a game.

After breakfast, Dagmar checked with Mr. Tong to see if anything had changed, and found that nothing had. So she went to her room, booted her ultrathin computer, and checked her email.

Her handheld could do anything her computer could, but she preferred a standard keyboard to having to thumb long messages on the phone’s little keypad. She wiped out spam, answered some routine queries, and sent messages to friends about her situation. She wrote about the riot and about being trapped in the music store, and about the bodies she thought she’d seen on the trip to the hotel.

As she typed on the familiar keyboard, in the hotel room that smelled of clean sheets, with the hushed sound of the air-conditioning in the background and the room’s coffeemaker hissing and snorting as it provided Dagmar’s caffeine fix, the previous day’s hazards began to seem unreal, a brief dip into a nightmare that had been banished by the morning’s strong tropical light.

The plangent sounds of Johnny Otis echoed in the room. Dagmar snatched at her phone. The number flashing in the display had a country code she didn’t recognize.

“Hello?” she said cautiously.

“Is this Dagmar Shaw?”

The male voice had some kind of Eastern European accent.

“Yes,” she said.

“My name is Tomer Zan,” the man said. “I work for Zelazni Associates. Your employer, Mr. Ruff, has retained us to see about your safety.”

Dagmar restrained her impulse to begin a joyful bouncing on the mattress.

“Yes,” she said. “He told me to expect your call.”

“Can you describe your situation, please?”

She did. She mentioned the riot the previous day, and being trapped in the music store, and the fact that she had $180 in cash. She told Tomer Zan that she was on the fourteenth floor of the hotel, with a view to the northwest. She mentioned that meals were no longer being served on the third-floor terrace because the hotel management considered it unsafe.

“I’m looking at a satellite picture of your hotel on Google Earth,” Zan said, “and I can tell you right now that I don’t like it. You’re too close to that traffic circle with the Welcome Statue, you’re too close to the government buildings that are going to be targets for demonstrators. The natural path for marches or riots runs right past your front door.”

“Great,” Dagmar said.

“We’re going to try to move you someplace safer. But we don’t have any assets in Jakarta, so that may not be possible for a few days.”

Dagmar felt her mouth go dry.

“You don’t have anybody in Jakarta?” she asked.

“No, we don’t.”

“So why did Charlie hire you?”

“Because,” Zan explained patiently, “the companies with assets in Jakarta are all overcommitted right now.”

Figures, Dagmar thought. She wandered to the window, parted the heavy curtains, and looked down at the street below. There was very little traffic, and none on foot. And no police.

“We’ll have someone on the ground there in a few days,” Zan said.

He seemed very confident of this.

“Okay,” she said.

“You’re not with anyone?” Zan asked.

“No. I’m alone.”

“Okay. I want you to change your schedule every day. Eat meals at different times, and in different restaurants in the hotel, if that’s possible.”

“Why?”

“It takes three days to set up a kidnapping. If you keep changing your schedule, that makes an abduction more difficult.”

Dagmar began to say, But why would they kidnap me? then clacked her teeth shut on the words because they sounded just like the sort of thing a stupid tourist would say.

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll do that.”

“The power supply may be erratic, so keep your cell phone and your computer charged. Buy extra batteries if you can-or make sure your miniturbines have extra fuel.”

“My phone doesn’t have miniturbines.”

“Then charge it every chance you can, and buy extra batteries if you can find them in the hotel. And don’t use the phone for anything except absolutely necessary calls.”

“All right.”

“If there’s a store in the hotel where you can buy food, buy all you can. Even if it’s junk food. The average city has only a three-day supply of food, and calories may get scarce.”

“What do I buy the food with? Do I use my dollars?”

There was a long moment’s silence.

“Save the dollars,” Zan said.

He then went on to tell Dagmar that he wanted her to find six different ways to escape the hotel from her room. And another six exits from every other place she regularly visited within the building.

“What do I do if I have to leave the hotel?”

“Find a place of temporary safety, and call me.”

He went on to tell her not to wear any expensive jewelry or be seen carrying her computer, because that might mark her out as someone worth robbing.

“Another thing,” he said. “I need you to be on the roof of the hotel at sixteen hundred hours Jakarta time.”

“This afternoon?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“So the satellite can get a look at you. I need you facing east and looking up.”

Dagmar wondered how much it was costing Charlie to retask someone’s satellite, and decided it was better not to know.

“You can use my picture on the Great Big Idea Web page,” she said.

“We’re getting pictures of the roof anyway,” Zan said, “in case we want to extract you from there. So we might as well find out what you look like now.”

Extract, Dagmar thought.

“All right,” she said.

She was placing herself in the hands of experts. Not that it had worked so far.

Tomer Zan advised her to keep her passport and money on her, preferably in a money belt, or in a pocket that could be buttoned or zipped.

“I have a pouch I can wear around my neck,” she said. Which she rarely used, because it wasn’t designed for people with tits.

“That’s good,” Zan said. “Would you like me to repeat any of my instructions?”

“Change my schedule,” Dagmar said. “Six exits, no jewelry or computer in public, on the roof at sixteen hundred.”

“You forgot to buy batteries,” Zan said. His voice betrayed absolutely no sense of humor.

“Buy batteries,” Dagmar said. “Check.”

“Don’t lose this number. I’ll send you email in a few minutes repeating everything I’ve said.”

“Okay.”

Zan said good-bye and hung up. Dagmar located his number in her phone’s memory and shifted it into the directory under the name Charlies Friend.

Ten minutes later, Zan’s email turned up on her computer.

Dagmar decided she might as well go find batteries.

A woman in a hotel room, Dagmar thought a few hours later. That would be a good place to start a story.

You would have plenty of issues to deal with right away. Who was the woman, and why was she in the hotel room? Where was the hotel? What was going on outside? Was she in transit, in hiding, on the phone, in denial?

Probably all four, Dagmar thought, and felt an uneasy pang of self-knowledge.

The sad fact was that every sad fact in the world was the raw material for a story. Fiction thrived on desperation, on dejection, on violence. Every time you stepped outside the door, you could find a new subject. Every book and newspaper became research. Every act, no matter how sordid, and every tragedy, no matter how pointless, was matter for fiction-and in fiction, all tragedy has meaning and no action is random.

So you start with the woman in the hotel room, Dagmar thought. And the reason she is there is that she has no place else to go.

CHAPTER SIX This Is Not the BatCave

The screen was full of chaotic movement, explosions, the clash of weapons. BJ’s fingers danced over the controller. The ice-cold Entropy Beast that hovered over the chamber exploded in a blast of flame, scattering chunks of frozen flesh-shrapnel and knocking down half a dozen Goblin Warriors and one Lawful Paladin.

“No,” BJ said, “you can’t download all of ‘Fly Like an Eagle’ as a ring tone.”

The Paladin sprang back to his feet and cut a Goblin Warrior in half with his Fire Sword.

“No,” BJ said, “it doesn’t matter if your friend says he did it. You still can’t. If you have the right software, you can convert a sound file into a ring tone and download it from your own computer, but we don’t provide that service.”

Explosions rocked the stone castle walls. BJ’s Elven Mage-who had the advantage of being invisible, at least as far as the other players were concerned-scuttled up the staircase and toward the glowing chest on the Altar of the Black Goddess.

“Thank you, ma’am,” said BJ. “Sorry I wasn’t able to help.”

BJ worked in the darkest, most depressing dungeon of information technology, that of customer service. He spent his hours aiding the inept, the insane, and a very large population of compulsive liars. It was that last category that drove him into a fury-couldn’t any of these people tell the simple truth? They chanted their mantra-“I didn’t do anything”-when it was clear that they had been ravaging their own software with one deranged decision after another.

Fortunately, Spud LLC-“Your source for user-friendly IT solutions”-didn’t much care that BJ ran his own little gold-farming projects on the side.

“Let’s try this,” BJ said. “Try restarting your computer. If you still have a problem, call me back.”

His Elven Mage was the first of the party to the casket on the Black Goddess’s altar. BJ knew that once he magicked open the casket, he had approximately thirty-four seconds before the Goddess Herself materialized in the chamber to lay waste to any intruders, whether they were invisible or not. BJ planned to be out of the room by then.

“Your email program won’t respond to the password? Indulge me for a moment-have you checked to see if the Caps Lock key is on?”

The Elven Mage touched the glowing casket. A balloon appeared in a corner of the screen. BJ moused to the balloon and typed in the Pre-Adamite spell that would open the casket. With the sound of flourishing trumpets-a sound that BJ hoped would be obscured from other players by the general sound of combat going on below-the glowing casket opened.

The countdown had started.

BJ clicked the Grab button, and the Elven Mage glommed the two items in the casket, a scroll of spells and the Orb of Healing. The spells on the scroll were low-level crap, but BJ could maybe trade the item for something more useful. The Orb of Healing, however, was the big prize on this level, and BJ wasn’t about to give it up.

The Elven Mage scurried down the stairs and snaked through the battling warriors. The Paladin was still cleaving Goblins in twain. The Dwarf Twins were fighting to protect the Enchanter, who in turn was casting spells, fireballs exploding with little mushroom clouds like atomic bombs, and the Halfling was hanging around in the background and throwing flaming bottles of oil at the Goblins.

If they were still in the room when the Dark Goddess showed up, they were all going to become extinct.

BJ didn’t much care-he’d gotten what he came for, and if none of his party survived, there wouldn’t be any argument over how to split the loot.

Besides, the Orb of Healing was unsplittable.

“Let’s try restarting your computer,” BJ said. “If you still have a problem, call me back.”

The Elven Mage ducked through the Gothic arch at the far end of the room and ran past the splintered bodies of two Guardian Gargoyles. Behind him, he heard the chiming chords that accompanied the appearance of the Dark Goddess, followed by the sounds of a lot of dying.

Stupid noobs, BJ thought. And when the Dark Goddess disapparated, he could reenter the room and pick up the gold and possessions of his deceased companions.

That Fire Sword would come in handy… for somebody.

BJ had just made anywhere between six hundred and a thousand dollars-real dollars, not the virtual gold pieces used in the game. More if he could pick up the Fire Sword.

BJ had played the Adventure of the Orb so many times that he could practically do it with his eyes closed. He could do it with perfect competence even when performing his customer service job. But though the adventure was by now tedious in the extreme, the tedium was worth it in terms of income.

The fact was that there were a lot of players who didn’t want to play the lower levels of online games like World of Cinnabar. They wanted to start powerful characters right away and were willing to pay-pay real money-for those characters and for powerful magic items like the Orb of Healing. It was against the rules of the World of Cinnabar for money to be exchanged for these virtual items, but there was no practical way for game administrators-or those of any other MMORPG-to police eBay or the many other auction sites.

The Orb alone, when auctioned online, would net BJ at least three hundred dollars. His Level Twelve Elven Mage, with all its loot and gear, would net him another three hundred. If he was lucky, the auction could go higher.

Not bad for the thirty online hours it had taken to raise the Mage to his present level-even if competition from a thousand Chinese boiler-room gold farms had depressed prices.