Robert McCammon

Mister Slaughter

PART ONE: The Monster's Tooth

One

Listen! Said the October wind, as it swirled and swooped through the streets of New York. I have a story to tell!

About change in the weather, and the whethers of men! Whether this one staggering past, the spindly gent, shall right himself against my onslaught before I take him to the wall, or whether that one there, with his prodigious belly, shall be fast enough to catch his tricorn as I throw it from his head! With a shove and a shriek I pass through the town, and what fast horse might ride me down?

None, thought Matthew Corbett in reply.

To be sure! Respect my comings and goings, and knowthat something unseen may prove a force no man may master.

Of that Matthew was undeniably certain, for he was having one devil of a time holding onto his own tricorn and balancing himself against the blasts.

It was near eight-thirty on a Thursday night, this second week of October. The young man was on a mission. He had been told to be at the corner of Stone and Broad streets at half past eight, and if he valued his hide he would report as ordered. Hudson Greathouse, his associate and senior member of the Herrald Agency, was in no mood these days to brook Matthew any easement concerning who was the boss and who was well; it was true enough, the slave.

But, as Matthew continued his brisk battle south along Queen Street with other citizens seemingly pushing against invisible walls in one direction or flying like bundles of empty clothes past him in the other, he thought that Greathouse's harsh attitude of late had more to do with celebrity than slavery.

After all, Matthew was famous.

Your hat's getting a bit high, don't you think? Greathouse had often asked since the successful conclusion of the mystery concerning the Queen of Bedlam.

Yes, Matthew had answered, as calmly as possible when faced with a human bull ready to charge any utterance that had the agitation of a red flag. But I do wear it well. Which was not enough to make the bull charge, but enough to make it snort with ominous anticipation of future violence.

The truth being, Matthew really was a celebrity. His exploits to determine the identity of the Masker and his near demise at the Chapel estate in the summer had given the town's printmaster, Marmaduke Grigsby, enough material for a barrage of Earwigs that made the broadsheet even more popular than the Saturday night dogfights up at Peck's Wharf. The initial story, written right after the end of the episode in July, had been restrained and factual enough, due to High Constable Gardner Lillehorne's threats to set fire to the printing press, but after Marmaduke's granddaughter Berry had detailed her own part in the picture the old newshound had nearly begun baying at the moon outside Matthew's residence, which was a refurbished dairyhouse just behind Grigsby's own home and printshop.

Out of decorum and common sense, Matthew had resisted telling the particulars of the tale, but in time his defenses had been weakened and finally crushed. By the third week of September the "Untold Story of our Own Matthew Corbett's Adventure with Venomous Villains and Threat of A Hideous Death, Part the First" was set in type, and the flames of industry-and the Grigsby imagination-had really started burning.

Whereas one day Matthew was simply a young man of twenty-three who had risen by fate and circumstance from New York orphan to magistrate's clerk to an associate "problem solver" at the London-based Herrald Agency, he was by the following afternoon being trailed by an ever-swelling mob of people who thrust upon him quills, inkpots and Earwigs so as to sign his name across the premier chapter of this adventure, which he hardly recognized anymore as being his own experience. It was apparent that whatever Marmaduke did not know for sure, he was certain to invent.

By the third and final chapter, published last week, Matthew had been transformed from a simple citizen among the nearly five-thousand other New Yorkers of 1702 into a knight of justice who had not only prevented the collapse of the colony's economic underpinnings but also saved every maiden of the town from being ravished by Chapel's minions. Running with Berry for their lives across a dead vineyard with fifty killers and ten trained vultures at their backs? Fighting a trio of blood-crazed Prussian swordsmen? Well, there was a seed of truth at the center of this fiction, but the fruit around it was a fantasy.

Nevertheless, the series had been a boon for Grigsby and the Earwig, and was much discussed not only in the taverns but around the wells and horse troughs. It was said that even Governor Lord Cornbury had been seen strolling the Broad Way one afternoon, wearing a yellow wig, white gloves and his feminine finery in tribute to his cousin, Queen Anne, as he read the most recent broadsheet with rapt, purple-painted eyes.

A gritty gust at the intersection of Queen and Wall streets whirled around Matthew the commingled aromas of fish, tarbuckets, wharf pilings, stockyard animals and their fodder, the contents of chamberpots thrown from house windows onto the cobblestones, and the bittersweet winey smell of the East River at night. If Matthew was not in the heart of New York, he was surely in its nose.

The wind had whipped into many of the lanterns that hung from street-corner posts and put the quit to their flames. Every seventh house was required by law to hang out a lamp, but tonight no man-not the wandering constables nor even their chief Lillehorne, for all his own puffery-might command the wind to spare a wick. This unceasing tumult, which had begun around five o'clock and showed no signs of abatement, had brought Matthew to his philosophical mental discussion with the bellowing bully. He had to hurry now, for even without consulting the silver watch in his waistcoat pocket he knew he was a few minutes late.

Soon enough, with the wind now pushing at his back, Matthew crossed the cobbles of Broad Street and by the tortured candle of a remaining lamp spied his taskmaster waiting for him ahead. Their office was only a little further along Stone Street at Number Seven, up a flight of narrow stairs into a loft said to be haunted by the previous tenants who'd murdered each other over coffee beans. Matthew had heard a few creaks and thumps in the last few weeks, but he was sure those were just the complaints of Dutch building stones settling into English earth.

Before Matthew could fully reach Hudson Greathouse, who wore a woolen monmouth cap and a long dark cloak that flailed about him like raven's wings, the other man strode forward to meet him and, in passing, said loudly against the blast, "Follow me!"

Matthew did, almost losing his tricorn once more when he turned to retrace his path. Greathouse walked into the wind as if he owned it.

"Where are we going?" Matthew shouted, but either his voice was swept away or Greathouse chose not to answer.

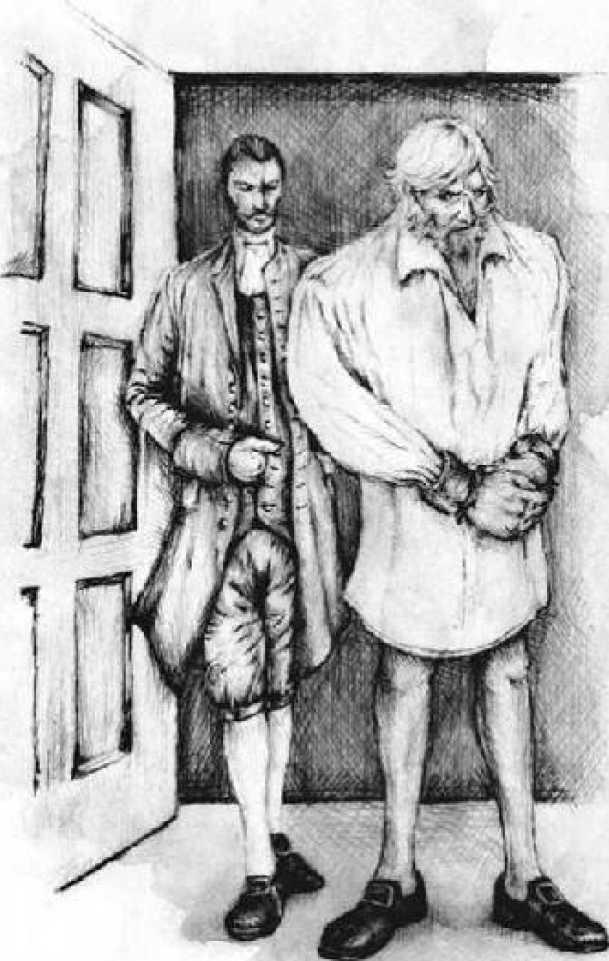

Though bound together in service to the Herrald Agency, the two "problem-solvers" could never be taken for brothers. Matthew was tall and slim, yet with the toughness of a river reed about him. He had a lean long-jawed face and a thatch of fine black hair under his ebony tricorn. His pale candlelit countenance attested to his interest in books and nighttime games of chess at his favorite tavern, the Trot Then Gallop. Due to his recent celebrity, and the fact that he thought himself deserving of such status since he really had almost been killed in defense of justice, he'd taken an interest in dressing as a New York gentleman should. In his new black suit and waistcoat with fine gray stripes, one of two outfits tailored for him by Benjamin Owles, he was every bit the Jack O'Dandy. His new black boots, just delivered on Monday, were polished to a glossy shine. He had an order in for a blackthorn walking-stick, which he'd noted many young gentlemen of importance in the town carrying about, but as this item had to be shipped from London he wouldn't enjoy its company until springtime. He kept himself clean as a soapdish and shaved to the pink. His cool gray eyes with their hints of twilight blue were clear and on this night untroubled. They cast a direct and steady gaze that some might say-and as Grigsby had said, in the second chapter-"could cause the ruffian to lay down his burden of evil lest it prove as heavy as prison chains."

That old inkthrower sure knew how to turn a phrase, Matthew thought.

Hudson Greathouse, who had turned to the left and was now striding several lengths ahead north along Broad Street, was in contrast to Matthew a hammer versus a lockpick. At age forty-seven, he was a broad-shouldered strapper who stood three inches over six feet, a height and dimension that upon meeting him caused most other men to look down at the ground to find their courage. When the craggy-faced Greathouse cast his deep-set black eyes around a room, the men in that room quite simply seemed to freeze for fear of catching his attention. The opposite effect was induced upon the women, for Matthew had seen the churchiest of ladies become a twittering flirt within scent of Greathouse's lime shaving soap. Also in contrast to Matthew, the great one had no use for the whims of current fashion. An expensively-tailored suit was out of the question; the most he'd go was a pale blue ruffled shirt, clean but well-worn, to accompany plain gray knee breeches, simple white stockings, and sturdy, unpolished boots. Under his cap his thick hair was iron-gray, pulled back into a queue and tied with a black ribbon.

f the two had anythi ng i n common other than the Herrald Agency, it was the scars they each wore. Matthew's badge of honor was a crescent that began just above the right eyebrow and curved into the hairline, a lifelong reminder of a battle in the wilderness with a bear three years ago, and lucky he was to still be walking the earth. Greathouse bore a jagged scar that sliced through the left eyebrow, and was-as he had explained in a petulant voice-presented to him by a broken teacup thrown by his third wife. Ex-wife, of course, and Matthew had never asked what had become of her. But, to be fair, Greathouse's real collection of scars-from an assassin's dagger, a musket ball, and a rapier swing-was worn beneath his shirt.

They were approaching the three-story edifice of City Hall, built of yellow stone, that stood where Broad Street met Wall. Lantern lights showed in some of the windows, as the business of the town demanded late hours. Scaffolding stood alongside the building; a cupola was being erected on the roof's highest point, the better to display a Union flag nearer Heaven. Matthew wondered how the town's coroner, the efficient but eccentric Ashton McCaggers, liked hearing the workmen hammering and sawing up there over his head, since he lived in his strange museum of skeletons and grisly artifacts in City Hall's attic. Matthew mused also, as Greathouse turned to the right and began walking along Wall Street toward the harbor, that McCaggers' slave Zed would soon be up in the cupola looking out over the thriving town and seaport, for Matthew knew the giant African enjoyed sitting silently on the roof while the world bargained, sweated, swore, and generally thrashed at itself below.

Not much further, past the Cat's Paw tavern on the left, and Matthew realized where Greathouse was taking him.

Since the Masker's reign of terror had ended at midsummer, there'd been no more murders in town. If Matthew were to volunteer to a visitor the most likely place to witness a killing, it would be behind the scabby red door that Greathouse now approached. Above that door was a weatherbeaten red sign proclaiming The Cock'a'tail. The tavern's front window had been shattered so many times by fighting patrons that it was simply sealed over with rough planks, through which dirty light leaked onto Wall Street. Of the dozen-odd taverns in New York, this was the one Matthew most studiously avoided. The mix of rogues and high-pockets who thought themselves financial wizards were fueled here in their arguments over the value of such commodities as head souse and beaver pelts by the cheapest, nastiest and most potent apple brandy ever to inflame a brain.

Distressingly for Matthew, Greathouse opened the door and turned to motion him in. The yellow lamplight vomited out a fog of pipesmoke that was at once carried off by the wind. Matthew clenched his teeth, and as he approached the evil-looking doorway he saw a streak of lightning dance across the dark and heard the kettledrum of thunder up where God watched over damned fools. "Shut that door!" immediately bawled a voice that both blasted and croaked, like a cannon firing a load of bullfrogs. "You're lettin' out the stink!"

"Well," Greathouse said with a gracious smile, as Matthew stepped into the rancid room. "We can't have that, can we?" He shut the door, and the skinny gray-bearded gent who was sitting in a chair at the back, having been interrupted in his massacre of a good fiddle, instantly returned to his display of screeching aural violence.

The cannon-voiced bullfrog behind the bar, whose name was Lionel Skelly and whose fiery red beard almost reached the bottom of his stained leather waistcoat, resumed his task of pouring a fresh-to use a word imperfectly-mug of apple destruction for a patron who turned a fishy eye upon the new arrivals.

"What, ho!" said Samuel Baiter, a man known to have bitten off a nose or two. To add to his charms, he was a heavy gambler, a vicious wife-beater, and spent much of his time with the ladies at Polly Blossom's rose-colored house on Petticoat Lane. He had the flat, cruel face and stubby nose of a brawler, and Matthew realized the man was either too drunk or too stupid to be cowed by Hudson Greathouse. "The young hero and his keeper! Come, have a drink with us!" Baiter grinned and lifted his mug, which slopped oily brown liquid onto the floorboards.

The second man in that declaration of "us" was a new figure in town, having arrived in the middle of September from England. He was almost as big as Greathouse, with huge square shoulders that strained his dark brown suit. He'd removed his tricorn, which was the same shade of Broad Way mud, to display why he was called "Bonehead" Boskins. His scalp was completely bald. His broad forehead protruded over a pair of heavy black eyebrows like, indeed, a wall of bone. Matthew didn't know much about Boskins, other than he was in his early thirties and unemployed, but had ambitions of getting into the fur trade. The man smoked a clay pipe and looked from Matthew to Greathouse and back again with small, pale blue eyes that, if showing any emotion at all, displayed utter indifference.

"We're expecting someone," Greathouse answered, his voice light and easy. "But another time, I'm sure." Without waiting for a response, he grasped Matthew's elbow and guided the younger man to a table. "Sit," Greathouse said under his breath, and Matthew scraped a chair back and eased himself down.

"As you please." Baiter quaffed from his drink and then lifted it high. He summoned a half-lipped smile. "To the young hero, then. I hear Polly's quite taken with you these days."

Greathouse sat down with his back toward the corner, his expression relaxed. Matthew took the measure of the room. Ten or twelve dirty lanterns hung overhead, from the end of chains on hooks in the smoke-greased rafters. Under a floating cloud of pipesmoke there were seven other men and one blowsy lady in attendance, two of the men passed out with their heads in a gray puddle of what might have been clam chowder on their table. No, there was an eighth man too, also passed out and face-down at the table to Matthew's left, and as Matthew recognized the green-glassed lantern of a town constable Dippen Nack lifted his swollen-eyed face and struggled to focus. Beside an overturned mug was the brutish little constable's black billyclub.

"You," Nack rasped, and then his forehead thumped down upon the wood.

"Quite taken," Baiter went on, obviously more stupid than drunk. "With your adventures, I mean. I've heard she's offered you a what did she call it? a 'season pass'?"

The invitation, on elegant stationery, had indeed arrived at Matthew's office soon after the first chapter was published. He had no intention of redeeming it, but he appreciated the gesture.

"You've read about Matthew Corbett, haven't you, Bonehead? If it wasn't for him, we couldn't walk the streets safe at night, could we? Couldn't even go out for a drink and a poke. Well, Polly talks about him all the time," said Baiter, with an edge of harshness creeping in. "About what a gentleman he is. How smart, and how noble. As if the rest of us men were just little creatures to be tolerated. Little useless creatures, but oh how that whore can go on about him!"

"I think the whole damned thing was made up, is what I think!" said the blowsy lady, whose sausage-skin was a gown thirty pounds ago. "Ain't nobody could live, fightin' fifty men! Ain't that what I think, George?" When there was no reply, she kicked the chair of one of the unconscious patrons and he answered with a muffled groan.

"Fifty men!" Dippen Nack lifted his head again. The sweat of effort sparkled on his ruddy, cherub-cheeked face. The constable was, in Matthew's opinion, though, closer to a devil than a cherub. Anybody who stole the gaol keys and went in at night to pee on the prisoners did not rate high in his book of life. "A damned lie! And me, boppin' that Evans bastard on the bopper and savin' Corbett's life, and not even gettin' my name in that rag! Takin' a knife in the arm for my trouble, too! It ain't fair!" Nack made a strangled sound, as if he were about to start crying.

"Sure he's a liar, Sam," said Bonehead, with a small sip from his own mug, "but that's a fine suit he's wearin'. Fittin', for such a smart cock to strut around in. How much that suit cost you?" This was spoken as Bonehead stared into the depths of his drink.

Now Matthew began to suspect why Greathouse had brought him here. Of all places, to the tavern where he knew two men had died in brutal fights right on this floor, which looked to him to be more blood-stained than brandy-splashed. Having clerked for Magistrate Nathaniel Powers, Matthew also knew that Lionel Skelly himself was no stranger to violence; the tavern keeper had cut off a man's hand with an axe he kept behind the bar. It didn't pay to try to swipe coins from the cashbox in here.

Greathouse spoke up, to parry the question: "Way too much, in my opinion."

There was a silence.

Bonehead Boskins slowly put his mug on the bar and aimed his eyes at Greathouse. Now he looked every inch a man who was neither too drunk nor too stupid but perhaps just enough of both to light his wick. In fact, he looked supremely confident in his ability to maim. Indeed, eager. "I was speakin' to the young hero," he said. "Not to you, old man."

Yep, Matthew thought as his heartbeat quickened and his guts went squirmy. Sure as rain. The crazed maniac had brought them here to get into a fight. It wasn't enough that Matthew had been doing very well in his arduous lessons on swordplay, map-making, preparing and firing a flintlock pistol, horsemanship and other such necessities of the trade. No, he wasn't progressing fast enough in that "fist combat" nonsense that Greathouse imposed upon him. Remember, Greathouse had said many times, you fight with your mind before you use your muscles.

It seemed that Matthew was about to get a demonstration of the great one's mind. And Heaven help us, he thought.

Greathouse stood up. He was still smiling, though the smile had thinned.

Matthew again counted the heads. The fiddler had stopped his fiddling. Was he a fighter, or a fixture? George and his unconscious companion were still face-down, but they might come to life at the first smack. Who could say what Dippen Nack would do? The blowsy lady was grinning; her front teeth had already been knocked out. Baiter would probably wait for Bonehead to bash a skull before he started nose-chewing. Skelly's axe was always near at hand. Of the five others, two looked like rough-edged wharfmen who craved a good bustarole. The remaining three, at a back table, were dressed in nice suits that they might not want to disfigure and were puffing on churchwarden pipes, though certainly they were no reverends. A throw of the dice, Matthew thought, but he really hoped Greathouse was not such a careless gamesman.

Instead of advancing on Bonehead, Greathouse casually removed his cap and cloak and hung them on wallpegs. "We just came in to spend a little time. As I said, we're expecting someone. Neither Mr. Corbett nor I want any trouble."

Expecting someone? Matthew had no idea what the man was talking about.

"Who're you expectin'?" Bonehead leaned against the bar and crossed his thick arms. A seam at the shoulder was threatening to burst. "Your lady friend, Lord Cornhole?" Beside him, Baiter sniggered.

"No," Greathouse replied, "we're expecting a man I might hire to join our agency. I thought this would be an interesting place to meet." At that moment, the door opened, Matthew saw a shadow on the threshold, heard the clump of boots, and Greathouse said, "Here he is now!"

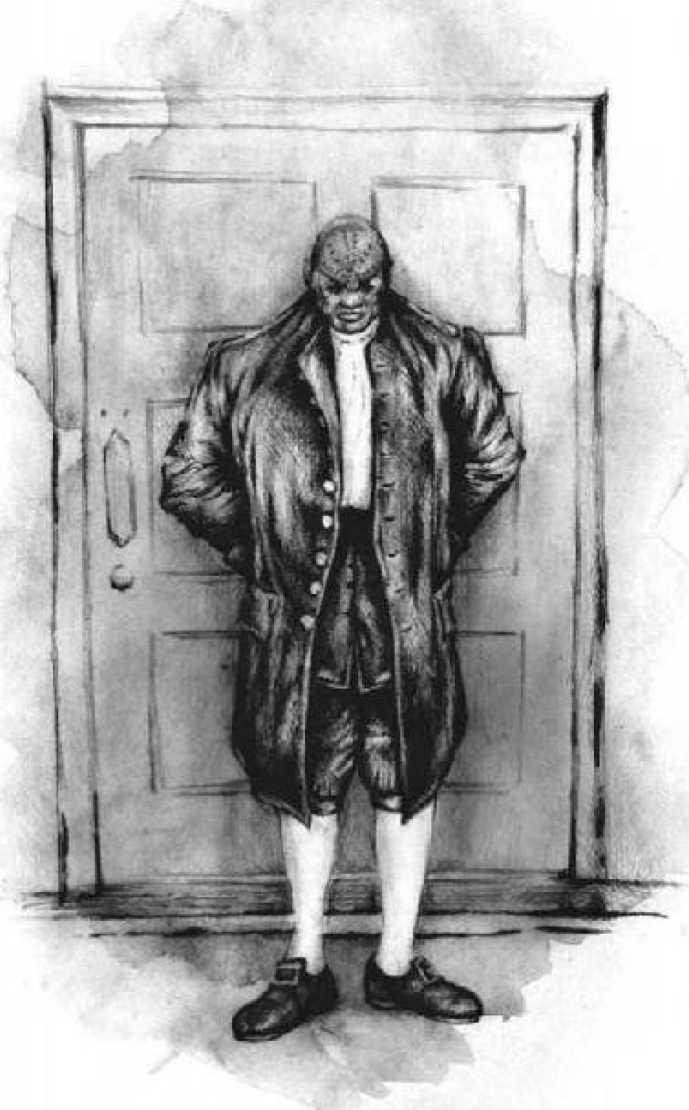

Zed the slave walked in, wearing a black suit, white stockings and a white silk cravat.

As the place went quiet except for an inrush of breath and Matthew's eyes bulged in their sockets, Matthew looked at Greathouse with an effort that almost broke his neck and managed to say, "Have you gone mad?"

Two

Mad or not, Greathouse had a gleam in his eye and a measure of pride in his voice when he next addressed the slave: "Well! Don't you look upright!"

How much of this praise Zed understood was unknown. The slave stood with his back against the door, his wide shoulders slightly bowed as if he feared disturbing the tavern's precarious peace. His black, fathomless eyes moved from Greathouse to take in the other patrons and then back again, in what was almost to Matthew's viewpoint a gaze of supplication. Zed didn't want to be here, no more than he was wanted.

"That's the coroner's crow!" came a shrill cry from the lady. "I seen him carryin' a dead man easy as a sack a'feathers!"

This was no exaggeration. Zed's tasks in service to Ashton McCaggers included the cartage of bodies from the streets. Matthew had also witnessed the slave's formidable feats of strength, down in the cold room in City Hall's cellar.

Zed was bald and massive, nearly the same height as Hudson Greathouse but broader across the back, shoulders and chest. To look upon him was to view in its full and mysterious force all the power of the dark continent, and so black was he that his flesh seemed to radiate a blue glow under the yellow lamps. Upon his face-cheeks, forehead and chin-were tribal scars that lay upraised on the skin, and in these were the stylized Z, E, and D by which McCaggers had named him. McCaggers had evidently taught him some rudimentary English to perform his job but, alas, could not teach him to speak, for Zed's tongue had been severed from its root long before the slaveship made fast to the Great Dock.

Speaking of tongues, Skelly found his. It threw forth a croaking blast from Hell: "Get that crowout of here!"

"It's against the law!" shouted Baiter, just as soon as Skelly's voice finished shaking sawdust from the rafters. His face, mottled with crimson, wore the rage of insult. "Get him out or we'll throw him out! Won't we, Bonehead?

"Law? 'Gainst what law? I'm a constable, by God!" Nack had begun to stir himself once more, but in his condition stirring was a far stretch from standing.

Bonehead had not responded to the threat his companion had just unsheathed; it appeared to Matthew that Bonehead was taking in the size of the new arrival, and Bonehead was not so thick-skulled as to wish to batter himself against that particular ram. Still, being as men are men and men who drink potent liquor become more mettlesome as the mug is drained, Bonehead took a slug of valor and said, though nearly speaking into his drink, "Damn right."

"Oh, gentlemen, let's not go down that path!" Greathouse offered his palms to the bar, affording Matthew a view of the small scars and knots on the man's well-used knuckles. "And surely, sir," he said, addressing Baiter, "you don't really respect any decree Lord Cornbury might have pulled from under his gown, do you?"

"I said," came the tavern-keeper's voice, now not so much a croak as the metallic rasp of a pistol being cocked, "get that beast out of my sight!"

"And out of our noses, too," said one of the gentlemen at the rear, which told Matthew that they had no friends in this particular house.

"Very well, then." Greathouse shrugged, as if it was all done and sealed. "Just one drink for him, and we'll be gone."

"He'll drink my piss 'fore he gets a drop of my liquor!" hollered Skelly, and above Matthew the lanterns swayed on their chains. Skelly's eyes were wide and wild. His red beard, matted with the thousand-and-one grimes of New York, quivered like a viper's tail. Matthew heard the wind howl outside. Heard it shriek and whistle through chinks between the boards, as if trying to gnaw the place to splinters. The two wharfmen were on their feet, and one was cracking his knuckles. Why did men do that? Matthew wondered. To make their fists bigger?

Greathouse never lost his smile. "Tell you what. I'll buy a drink for myself. Then we'll leave everyone in peace. That suit you?" To Matthew's horror, the great man-the great fool!-was already walking to the bar, right up to where Bonehead and Baiter obviously longed to bash him down. Skelly stood where he was without moving, his mouth curled in a sneer, and when Matthew glanced at Zed he saw again that the slave had no interest in taking another step nearer destruction, much less getting a dirty mugful of it.

"He's gonna give it to the crow, is what he's thinkin'!" the lady protested, but it was already a thought in Matthew's mind.

We're expecting a man I might hire to join our agency, Greathouse had said.

Matthew had heard nothing of this. Hiring Zed? A slave who understood limited English and could speak not a word of it? Greathouse obviously needed no drink here, for he had ample supply of brain-killing liquor in his quarters at Mary Belovaire's boarding house.

As Greathouse approached the bar, Bonehead and Baiter moved away from him like cautious wolves. Matthew stood up, fearing a sudden burst of violence. "Don't you think we ought to-"

"Sit down," Greathouse answered firmly, with a quick glance back that had some warning in it. "Mind your manners, now, we're among good company."

Good company my assbone, Matthew thought. And, hesitantly, he sat down upon it.

The two wharfmen were edging nearer. Greathouse took no notice of them. Nack was rubbing his eyes, blinking at the huge black figure against the door. "One drink," Greathouse said to Skelly. "Your best, if you please." Skelly didn't move.

"I'm paying," said Greathouse, in a cool, calm voice, "for one drink." He reached into a pocket, brought out a coin and dropped it into the cashbox that sat atop the bar.

"Go ahead," Baiter spoke up, scowling. "Let him drink and get that black beast out of here, and to Hell with all

of 'em."

Greathouse's eyes never left those of the sullen tavern-keeper. "As the gentleman proposes," he said.

Suddenly Skelly smiled, but it was not a pretty sight. It revealed the broken black teeth in the front of his mouth, and showed that some faces wore a smile like the devil trying on a halo. It was just wrong. Because of that hideous smile, Matthew felt the danger in the room rachet up, like a bowstring tightening to loose an evil arrow.

"For sure, sir, for sure!" said Skelly, who then turned away to fetch a mug from a shelf and uncork a bottle of the usual nasty brandy. With a flourish, he poured into the mug a coin's worth. He thumped the mug down in front of Greathouse. "There you are, sir. Drink up!"

Greathouse paused, measuring the distance of Bonehead, Baiter and the two slowly approaching wharfmen. Now the three well-dressed gentlemen were on their feet, puffing their pipes and watching intently. Matthew stood up again, no matter what Greathouse had told him; he glanced at Zed and saw that even the slave was crouched in a position of readiness, but for what Matthew did not know.

Greathouse reached out and put his hand on the mug.

"One minute, sir," said Skelly. "You did say you wanted the best, didn't you? Well, lemme sweeten it for you." And, so saying, he leaned his head forward and drooled vile brown spittle into the drink. "There you are, sir," he said, again with that devil's smile, when he'd finished. "Now either you drink it, or let's see you give it to the crow."

Greathouse stared at the mug. "Hm," he said. His left eyebrow, the one with the teacup scar across it, began twitching. He said nothing more for a space of time. Bonehead began chuckling, and the lady just plain cackled. Dippen Nack gripped his constable's lantern and his black billyclub and began to try to stand up, but without a third arm he was having no luck at the task.

"Hm," Greathouse said again, inspecting the froth that bubbled atop the liquid.

"Drink up, then," Skelly offered. "Goes down smooth as shit, don't it, boys?"

To the credit of their good sense, no one answered.

Greathouse took his hand from the mug. He stared into Skelly's eyes. "I fear, sir, that I've lost my thirst. I beg your pardon for this intrusion, and I ask only that I might retrieve my coin, since my lips have not tasted of your

best."

"No, sir!" The smile disappeared as if slapped away. "You bought the drink! The coin stays!"

"But I have no doubt you can pour the liquor back into the bottle. As I'm sure you often do, when patrons are unable to finish their portions. Now I'll just take my coin and we'll be on our way." He began reaching toward the coinbox, and Matthew saw Skelly's right shoulder give a jerk. The bastard's hand had found that axe behind the bar.

"Hudson!" Matthew shouted, the blood pounding at his temples.

But the great man's hand would not be stopped. Greathouse and Skelly still stared at each other, locked in a silent test of wills, as one hand extended and another prepared to chop it off at the wrist.

In no particular hurry, Greathouse reached into the coinbox and let his fingers touch copper.

It was hard to tell exactly what happened next, for it happened with such ferocity and speed that Matthew thought everything was blurred and dreamlike, as if the mere scent of the brandy was enough to give a man the staggers.

He saw the axe come up, clenched hard in Skelly's hand. Saw the glint of lamplight on its business edge, and had the sure thought that Greathouse was going to miss tomorrow's rapier lesson. The axe rose up to its zenith and hung there for a second, as Skelly gritted his teeth and tensed to bring it crashing down through flesh, sinew and bone.

But here was the blurred part, for the axeblow was never delivered.

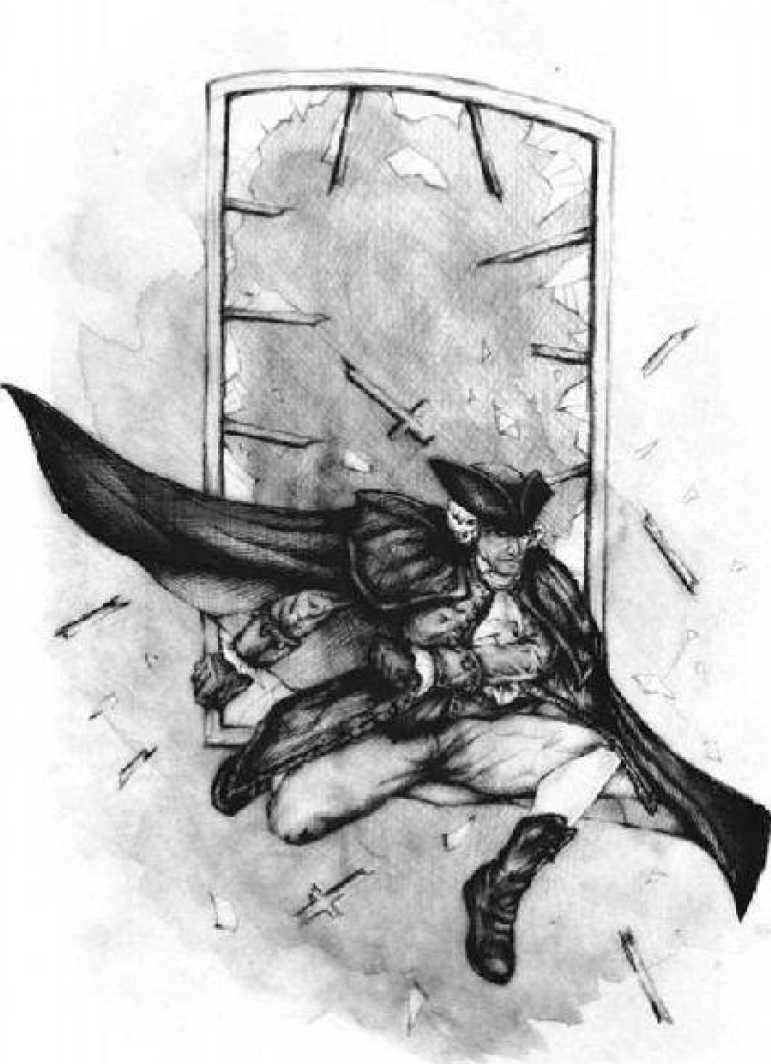

There came from the direction of the door a sound of Satan's minions thrashing in their chains, and Matthew turned his head fast enough to see Zed whipping out with the chain he'd just leaped up and wrenched off its hook from an overhead rafter. The chain still had a firelit lamp attached on the end Zed had thrown, and when it snapped across the room the chain not only wound itself around Skelly's upraised forearm, but the lamp hit Skelly midsection in the beard hard enough to shatter its glass sides. It was apparent in an instant that a blue flicker on a lump of wax might enjoy a feast of New York dirt and a week's drippings of apple brandy, for in a burst of eye-popping fire it consumed Skelly's beard like a wild dog would eat a muttonchop. As a thousand sparks flew around Skelly's face, Zed planted his boots and with one solid wrench of the chain pulled the old rapscallion over the bar as easily as hauling a catfish over the side of a skiff, the only difference being that a catfish still had whiskers.

Skelly hit the floor on his teeth, which perhaps was an improvement to the beauty of his dentals. Even with a mouthful of blood, he held firm to the axe. Zed began to haul him across the floor hand-over-hand, and with a tremendous ripping noise the back of the slave's suit coat split wide open as his back swelled. When Skelly was at his feet, Zed bent down, tore the axe loose and with an ease that looked like a child throwing jackstones he imbedded the axeblade in the nearest wall.

Some people, it seemed to Matthew, are born stupid. Which could be the only reason that, despite this display of fighting force, the two wharfmen jumped Greathouse from behind.

There was a flurry of fists and a barrage of cursing from the wharfmen, but then Greathouse had thrown them off with a shrug of disdain. Instead of smacking them both flat, as Matthew expected, he backed away from them. They made the supreme miscalculation of rushing after him, their teeth bared and their eyes drink-shiny.

They got perhaps two steps when a flying table hit them in their faces. The sound of noses breaking was not unmusical. As they went down writhing upon the planks, Matthew shuddered because he'd felt the wind of motion from Zed on the back of his neck, and he would not wish to be on the receiving end of that storm.

Skelly was spitting blood and croaking oaths on the floor, Baiter was backed up against a wall and looking for a way to squeeze through a crack, Bonehead drank down another swig of his brandy and watched things unfold with slitted eyes, and the blowsy lady was on her feet hollering names at Zed that made the very air blue with shame. At the same time, Greathouse and Matthew saw one of the gentlemen at the rear of the place-the one who'd remarked on the supposed offense done to his nose-slide a short sword from his cloak that hung on a wallpeg.

"If no one else will get that black bastard out," he announced with a thrust of his chin, "then allow me to run him through!"

Greathouse retreated. Now Matthew thought that surely it was time to head for the relative safety of the street. Yet Greathouse offered no suggestion for any of them to run for it, and instead that maddening half-smile was still stuck to his mouth.

As the swordsman came on, Zed looked at Greathouse with what Matthew thought might be a question, but whatever it might have asked it was disregarded. Dippen Nack had gotten himself standing, his billyclub lifted to apply his own brand of constable's justice. When he took a wobbly step toward Zed he was caught at the scruff of the neck by Greathouse, who looked at him, said a firm "Wo," and pushed him down into his chair as one would manage a child. Nack didn't try to stand again, which was just as well.

Giving out a horrendous screech, the lady of the house threw a mug at Zed with the intent of braining him. Before it reached its target, Zed caught the thing one-handed. With only a second's hesitation to take aim, Zed in turn threw the mug to smack against the swordsman's forehead, which laid the man out as if ready to be rolled into a coffin.

"Murr! Murr!" hollered Skelly, obviously wanting to cry Murder but finding his mouth not equal to the job. Still, he skittered past Zed like a dirty crab and burst through the door onto Wall Street, shouting " Murr! Murr!" and going straight for the Cat's Paw across the way.

Bonehead Boskins took the opportunity to act. He stepped forward, moving faster than any man his size might be expected to, and dashed the rest of his brandy directly into Zed's eyes.

The slave made a gutteral sound of pain and staggered back, both hands up to clear his vision, and so he did not see-as Matthew and Greathouse did-the brass implement of violence that Bonehead took from a pocket and deftly slipped upon the knuckles of his right fist.

Matthew had had enough of this. "Stop it!" he shouted, and moved to stand alongside Zed, but a hand grasped his coat and yanked him back out of harm's way.

"You just stand where you are," Greathouse said, in that tone he had that meant argument was a dead-end street.

Seeing Zed blinded by liquor, Baiter found his courage. He lunged forward and swung at Zed's skull, hitting him on the left cheekbone, and then gave him a kick on the right shin that made such a noise Matthew was sure the bone had cracked. Quite suddenly two black hands shot out, there was a ripping sound and Baiter had lost most of his shirt. An elbow was thrown, almost a casual movement. The stubby nose above Baiter's gaping mouth exploded so hard blood flew up among the lanterns. Baiter gave a cry like a baby for its mother and fell down upon the floor where he crawled up grasping against Bonehead's legs. The other man shouted, "Get away, damn it!" and kicked viciously to free himself even as Zed used Baiter's shirt to blot the last of the burning brandy out of his eyes.

Then, as Matthew knew it must, finally came the moment when the two bald-headed bulls must collide.

Bonehead waited for no other opportunity; with Baiter kicked aside and sobbing, Bonehead advanced a step and swung his brass widowmaker at Zed's face. The fist passed through empty air, for Zed had dodged the blow; was there one second, the next was not. A second blow had the same result. Bonehead crowded his opponent, the left arm up to deflect a strike and the right punching out with deadly purpose.

"Hit him! Hit him!" squalled the lady.

Bonehead had no lack of trying, and certainly no lack of brutal strength. What he lacked was success, for wherever the brass-knuckled fist struck, there Zed the slave was not. Faster and faster still went the blows, yet faster was Zed in dodging them. Sweat sparkled on Bonehead's brow and the breath heaved in his chest.

Hollering with drunken glee, a throng of men obviously from the Cat's Paw began to boil through the door, which hung half off its hinges due to Skelly's rough exit. Zed paid them no mind, his focus entirely on avoiding a brass kiss.

"Stand still and fight, you black coward!" Bonehead shouted, the spittle spraying from his mouth and his punches becoming wilder and weaker.

Desperate, Bonehead reached out with his left hand to grasp Zed's cravat, the better to hold him still, and no sooner had his fingers locked in silk did Zed's right arm cock back, the fist drove out squarely into Bonehead's jaw, and there came a solid and fearsome thunk of flesh on flesh that caused all the gleeful hollering to hush as if a religious vision had just been witnessed. Bonehead's eyes rolled back, his knees sagged, but he yet gripped hold of Zed and his own right fist was coming up in a blow that was more impulse than aimed, for it was obvious his brain had left the party.

Zed easily dodged it, with a small movement of his head. And then, in what men would later talk about from the Great Dock to the Post Road, Zed picked Bonehead Boskins up like a sack of cornmeal, swung him around and threw him, bonehead first, through the boarded-over window where so many other, yet so much smaller, victims of altercations had passed. When Bonehead crashed through on his way to a bruising encounter with Wall Street, the entire front wall shook so hard the men gathered there feared it would collapse on them and so retreated in a shrieking mass for their lives. The rafters groaned, sawdust fell, the chains creaked as their lanterns swung back and forth, and High Constable Gardner Lillehorne stood in the shattered doorway to shout, " What in the name of seven devils is going on in here?"

"Sir! Sir!" Nack was up again, staggering on his way to the door. Matthew noted that either the constable had spilled a drink in his lap, or was past need of a chamberpot. "Tried to stop it, sir! Swear I did!" He passed close to Zed and recoiled as if fearing to share Bonehead's method of departure.

"Oh, you shut up," Lillehorne answered. A rather eye-startling picture of fashion in a pumpkin-colored suit and tricorn and yellow stockings above polished brown boots, he came into the room and wrinkled his nose with disgust as he took stock of the scene. "Is anyone dead here?"

"That crow was gonna kill us all!" the lady shouted. She'd taken the liberty of seizing the unfinished mugs of brandy from the table where the wharfmen had been sitting, and had one in each hand. "Look what he did to these poor souls!"

Lillehorne tapped the palm of his gloved left hand with the silver lion's-head that adorned his black-lacquered cane. His long, pallid face with its carefully-trimmed black goatee and mustache surveyed the room, the narrow black eyes the same color as his hair, which some said was dyed liberally with India ink, and which was pulled back into a queue with a ribbon that matched his stockings.

Baiter was still mewling, clasping the ruin of his nose with both hands. The wharfmen were starting to stir, and one of them heaved forth a torrent of foul liquid that made Lillehorne gasp and press a yellow handkerchief to his pinched nostrils. George and his companion had gained consciousness but were still sitting at the table and blinking as if wondering what all the fuss was about. Two of the gentlemen were trying to revive the swordsman, whose legs began to jerk in an effort to outrun the mug that had knocked him into dreamland. At the far back of the room, the fiddler stood in a corner protecting his instrument. Out in the street, the gawkers shouted merrily as they peered through the door and the gaping aperture where Bonehead had passed through.

"Appalling," said Lillehorne. His cold gaze dismissed Matthew, fell upon the giant slave, who stood motionlessly and with his head lowered, and then came to rest on Hudson Greathouse. "I might have known you'd be here, when I heard Skelly hollering two streets away. You're the only one in town who could put such a fright in the old wretch that his beard flew off. Or is the slave responsible for all this mess?"

"I appreciate the compliment," said Greathouse, still wearing his self-satisfied and thoroughly infuriating smile. "But as I'm sure you'll find when you speak to the witnesses-the sober witnesses, that is-Mr. McCaggers' slave was simply preventing any physical harm to come to me or himself. I think he did a very able job."

Lillehorne again turned his attention to Zed, who stared fixedly at the floor. Outside, some of the shouts were turning nasty. Matthew heard "grave-digger's crow", "black beast", and worse, coupled with "murder" and "tar-and-feather".

"It's 'gainst the law!" Nack had suddenly remembered his station. "Sir! It's 'gainst the law for a slave to be in a public tavern!"

"Put him in the gaol!" the lady hollered between drinks. "Hell, put 'em all under the gaol!"

"The gaol?" Greathouse's brows lifted. "Oh, Gardner! Do you think that's really such a good idea? I mean three or four days in there-even one day-and I might be too weak to carry out my duties. And as I and I alone certainly admit arranging Mr. McCaggers' slave to meet me here, I would thus by law be the person to suffer."

"I think it ought to be the pillory, sir! For all of 'em!" Nack's evil little eyes gleamed. He pressed the tip of his billyclub against Matthew's chest. "Or the brandin' iron!"

Lillehorne said nothing for a moment. The shouts outside were becoming uglier still. He cocked his head, looking up first at Greathouse, then at Zed and back again. The high constable was a small-boned and slender man, standing several inches shorter than Matthew, and thus was dwarfed by the larger men. Even so, his ambition in the town of New York was the size of Goliath. To be mayor, nay, even the colony's governor someday was the bellow that fanned his flames. "Which will it be, sir?" Nack urged. "Pillory or iron?"

"The pillory may well be in use," Lillehorne replied without looking at Nack, "by a spineless constable who has gotten himself stinking drunk while on duty and allowed this infraction of the law on his watch. And mind you cease talking about irons before you find one branding your buttocks."

"But sir I mean " Nack sputtered, his face flaming red.

"Silence." Lillehorne waved him aside with the lion's-head. Then he stepped toward Greathouse and almost peered up the man's nostrils. "You hear me, sir. I'm not to be pushed, do you understand that? No matter what. Now, I don't know what game you've been playing at tonight and possibly I don't wish to know, but I don't want it to happen again. Is that clear, sir?"

"Absolutely," said Greathouse without hesitation.

"I demand satisfaction!" shouted the fallen swordsman, who was sitting up with a huge lump and blue bruise on his forehead.

"I'm satisfied that you're a fool, Mr. Giddins." Lillehorne's voice was calm and clear and utterly frigid. "There's a penalty of ten lashes for drawing a sword in a public place with intent to do bodily harm. Do you wish to proceed?"

Giddins said nothing, but reached out and retrieved his weapon.

The shouting in the street, which was drawing more men-certainly more drunkards and ruffians-from the other taverns, was increasing in volume and desire for justice in the form of violence. Zed kept his head down, and sweat was gathering on the back of Matthew's neck. Even Greathouse began to glance a little uneasily at the only way out.

"What I must do galls me sometimes," Lillehorne said. Then he looked into Matthew's face and sneered, "Aren't you tired of playing the young hero yet?" Without waiting for a reply, he said, "Come on, then. I'll walk you out of here. Nack, you'll stand guard 'til I send someone better." He started for the door, his cane up against his shoulder.

Greathouse got his cap and cloak and followed, then behind came Zed and Matthew. At their backs spewed dirty curses from the patrons who could still speak, and Nack's gaze shot daggers at the younger associate of the Herrald Agency.

Outside, the crowd of thirty or more men and a half-dozen drink-dazed women surged forward. "Get back! Everyone get back!" Lillehorne commanded, but even the voice of a high constable was not enough to douse the fires of this growing conflagration. Matthew knew full well that there were three things sure to draw a crowd in New York, day or night: a street hawker, a speechmaker, and the promise of a rowdy knockabout.

He saw through the crowd that Bonehead had survived his journey with but a gash on his brow and some blood trickling down his face, but he was still obviously less than fighting fit for he was careening around like a top, both fists swinging at the air. Somebody grabbed his arms to pin them, somebody else caught him around the waist, and then with a roar five other men leapt in and there was a free-for-all right there with Bonehead getting bashed and not even able to punch. A skinny old beggar held up a tambourine and began to rattle it around as he pranced back and forth, but someone with musical taste knocked it from his hand and then he began fighting and cursing like a wildman.

Still the citizens pressed in around their true quarry, which was Zed. They plucked at him and danced away. Someone came in to pull at his torn suitcoat, but Zed kept his head lowered and paid no mind. Ugly laughter-the laughter of brutes and cowards-whirled up. As he followed the slow and dangerous procession along Wall Street, Matthew suddenly noted that the wind had ceased blowing. The air was absolutely still, and smelled of the sea.

"Listen." Greathouse had drifted back to walk alongside Matthew. His voice was tight, a rare occurrence. "In the morning. Seven-thirty at Sally Almond's. I'll explain everything." He paused as he heard a bottle shatter against a wall. "If we get out of this," he added.

"Back! All of you!" Lillehorne was shouting. "I mean it, Spraggs! Let us pass, or I swear I'll brain you!" He lifted his cane, more for effect than anything else. The crowd was thickening, and now hands were balling into fists. "Nelson Routledge! Don't you have anything better to do than-"

He didn't finish what he was saying, for in the next instant no words were needed.

Zed lifted his head toward the ebony sky, and he made a noise from deep in his throat that began as the roar of a wounded bull and rose up and up, up to fearsome heights above the rooftops and chimneys, the docks and barns, the pens and stockyards and slaughterhouses. It began as the roar of a wounded bull, yes, but somewhere on its ascent it changed into the cry of a single child, alone and terrified in the dark.

The sound silenced all other noise. Afterwards, the cry could be heard rolling off across the town in one direction, across the water in the other.

All hands stilled. All fists came open, and all faces, even smirking, drink-swollen and mean-eyed, took on the tightness of shame about the mouth, for everyone in this throng knew a name for misery but had never heard it spoken with such horrible eloquence.

Zed once more lowered his head. Matthew stared at the ground. It was time for everyone to go home, to wives, husbands, lovers and children. To their own beds. Home, where they belonged.

The lightning flashed, the thunder spoke, and before the crowd began to move apart the rain fell upon them with ferocious force, as if the world had tilted on its axis and the cold sea was flooding down upon the land. Some ran for cover, others trudged slowly away with hunched shoulders and grim faces, and in a few minutes Wall Street lay empty in the deluge.

Three

"Very well, then." Matthew folded his hands before him on the table. He'd just hung his tricorn on a hook and sat down a moment before, but Greathouse was too taken with consuming his breakfast of eight eggs, four oily and glistening sausages, and six corncakes on a huge dark red platter to have paid him much attention. "What's the story?"

Greathouse paused in his feasting to sip from his cup of tea, which was as hot and as black as could be coaxed from the kitchen of Sally Almond's tavern on Nassau Street.

There could be no starker contrast between this esteemed establishment and the vile hole they'd visited last night. Whereas City Hall used to be the center of town, one might say that Sally's place-a tidy white stone building with a gray slate roof overhung by a huge oak tree-now claimed that position, as the streets and dwellings continued to grow northward. The tavern was warm and friendly and always smelled of mulling spices, smoked meats and freshly-baked pies. The floorboards were kept meticulously swept, vases of fresh flowers stood about, and the large fieldstone fireplace was put to good use at the first autumn chill. For breakfast, the midday meal and supper, Sally Almond's tavern did a brisk business among locals and travelers alike, in so much that Madam Almond herself often strolled about strumming a gittern and singing in a light, airy and extremely pleasing voice.

Rain had fallen all night, but had ceased near dawn. Through a large window that overlooked the pedestrians, the passing wagons, carts and livestock on Nassau Street could be seen beams of silver sunlight piercing the clouds. Directly across the street was the yellow brick boarding house of Mary Belovaire, where Greathouse was presently living until he found, as he put it, "more suitable quarters for a bachelor". His meaning was that Madam Belovaire, though being of a kind spirit, was wont to monitor the comings-and-goings of her lodgers, and go so far as to suggest they regularly attend church services, refrain from cursing and drinking, and generally comport themselves with great decorum as regards the opposite sex. All of which put Greathouse's large white teeth on the grind. The latest was that Madam Belovaire had been trying to matchmake him with a number of ladies she deemed respectable and upstanding, which in Greathouse's opinion made them as interesting as a bowlful of calfs-foot jelly. So it was no wonder that Greathouse had taken to spending some nights working at Number Seven Stone Street, but Matthew knew the man was sleeping on a cot up there in the company of a brandy bottle.

But not to say either of them had been bored in the last few weeks. Far from it. Since the Herrald Agency had been getting such publicity in the Earwig, there'd been no lack of letters and visitors presenting problems to be solved. Matthew had come to the aid of a young man who'd fallen in love with an Indian girl and wished to prove himself worthy before her father, the chief; there'd been the bizarre and disturbing night ride, in which Matthew had determined that not all the creatures on God's earth had been created by the hand of God; and there'd been the incident of the game of jingo and the gambler who'd had his prized horse cheated away from him by a gang of cutthroats. For Greathouse's part, there'd been his ordeal at the House at the Edge of the World that had so nearly cost him his life, and the eerie matter of the last will and testament of Dr. Coffin.

As Mrs. Herrald had told Matthew at dinner one night, back in midsummer when she'd offered him a position as a "problem-solver" with the agency her husband Richard had founded in London, You can be sure, Matthew, that the criminal element of not only England but also greater Europe is looking in this direction, and has already seen the potential. Whatever it might be: kidnapping, forgery, public and private theft, murder for hire. Domination of the mind and spirit, thereby to gain illicit profit. I could give you a list of the names of individual criminals who will most likely be lured here at some time or another, but it's not those petty thugs who concern me. Its the society that thrives underground, that pulls the marionette strings. The very powerful and very deadly group of men-and women-who even now are sitting at dinner just as we are, but they hold carving knives over a map of the new world and their appetites are ravenous.

So true, Matthew thought. He'd already come into contact with the man who held the largest knife, and sometimes in dark moments he imagined its blade pressing against his neck.

Greathouse put his cup down. He said, "Zed is a ga."

Matthew was sure he hadn't heard correctly. "A ga?"

"A ga," Greathouse answered. His gaze ticked to one side. "Here's Evelyn."

Evelyn Shelton, one of the tavern's two waitresses, was approaching their table. She had sparkling green eyes and blonde hair like a combed cloud, and as she was also a dancing instructress she was quite nimble on her feet at negotiating the morning crowd. Ivory and copper bracelets clicked and jingled on her wrists. "Matthew!" she said with a wide smile. "What might I get you?"

A new set of ears, he thought, as he still couldn't comprehend what a "ga" was. "Oh, I don't know. Do you have cracknel today?"

"Fresh baked."

"You might try the hot sausage," Greathouse urged as he chewed into another of the links. "Tell him how they'll make a man out of him, Evelyn."

Her laugh was like the ascending peal of glass bells. "Oh, they're spicy all right! But they go down the gullet so fast we can't keep 'em in stock! Only have 'em a few days a month as is, so if you want 'em you'd best get your order in!"

"I'll leave the fiery spice to Mr. Greathouse," Matthew decided. "I'll have the cracknel, a small bowl of rockahominy, some bacon and cider, thank you." He returned his attention across the table when the waitress had gone. "What exactly is a ga?"

"The Ga tribe. Whew, this is hot!" He had to blot his forehead with his napkin. "Damn tasty, though. Zed is a member of the Ga tribe. From the West African coast. I thought he might be, when you first described to me those scars on his face. They're given to some of the children at a very young age. Those determined to be suitable for training as warriors." He drank more tea, but obviously the sausage was compelling for he started immediately in on it again. "When I saw the scars for myself, the next step was finding out how well Zed could fight. I think he handled the situation very competently, don't you?"

"I think you could have been responsible for his death," Matthew said grimly. "And ours, as well."

"Shows how much you know. Ga warriors are among the finest hand-to-hand fighters in the world. Also, they have a reputation for being fearless. If anything, Zed held himself back last night. He could've broken the neck of every man in there and never raised a sweat."

"If that's so," Matthew said, "then why is he a slave? I'd think such a fearless warrior would have resisted the slaver's rope just a little bit."

"Ah." Greathouse nodded and chewed. "There you have a good point, which is exactly why I arranged with McCaggers to test him. It's very rare to find a Ga as a slave. See, McCaggers doesn't know what he's got. McCaggers wanted the biggest slave he could buy, to move corpses for him. He didn't know he was buying a fighting machine. But I needed to know just what Zed could do, and it seemed to me that the Cock'a'tail was the place to do it in."

"And your reasoning why this fighting machine became a slave, and why he just didn't fight his way out of his predicament?"

Greathouse ate a bite of corncake and tapped his fork quietly agai nst the platter. It was of i nterest to Matthew, as he waited for Greathouse to speak, that Sally Almond had bought all her plates and cups in that popular color called "Indian Blood" from Hiram Stokely, who'd begun to experiment with different glazes after rebuilding his pottery shop. Due to the rampage of Brutus the bull, the Stokely pottery was now doing twice the business it ever had.

"What put him in his predicament, as you call it," Greathouse finally replied, "will probably always be unknown. But I'd say that even one of the finest warriors in the world might be hit from behind by a cudgel, or trapped in a net and smothered down by six or seven men, or even have to make the choice to sacrifice himself that someone else might escape the chains. His people are fishermen, with a long heritage of seafaring. He might have been caught on a boat, with nowhere to go. I'd say he might have lost his tongue because he wouldn't give up the fight, and it was explained to him by some tender slaver that another body part would be the next sliced off. All possibilities, but as I say we'll likely never know."

"I'm surprised, then, that he just hasn't killed McCaggers and run for it."

"Now why would he want to do that?" Greathouse regarded Matthew as if he were looking at an imbecile. "Where would he go? And what would the point be? From my observation, McCaggers has been kind to him and Zed has responded by being as loyal " He paused, hunting his compass. "As loyal as a slave needs to be, given the situation. Also, it shows that Zed is intelligent. If he weren't, I'd have no interest in him. I wouldn't have paid the money for Benjamin Owles to sew him a decent suit, either."

"What?" Now this was getting serious. Greathouse had actually paid money for a suit? To be worn by McCaggers' slave? When he'd righted his senses, Matthew said, "Would you care to explain-as reasonably and rationally as possible-exactly why you have enough interest in Zed to entertain hiring him for the agency? Or was I dreaming that part of it?"

"No, you weren't dreaming. Here's your breakfast."

Evelyn had arrived bearing a tray with Matthew's food. She also showed an empty burlap bag, marked in red paint Mrs. Sutch's Sausages and, below that, the legend Sutch A Pleasure', to the other patrons in the room. "All out, kind friends!" Her announcement brought a chorus of boos and jeers, though in good nature. "We ought to be getting another shipment next month, which we'll post on the board outside."

"A popular item," Matthew remarked as Evelyn put his platter down before him.

"They refuse to believe it's gone until they see with their own eyes. If this lady didn't live so far away in Pennsylvania, I think Sally would go into business with her. But, anyway," she shrugged, "it's all in the spices. Anything else I can get for you?"

"No, this looks fine, thank you." When Evelyn retreated again and the hubbub died down, Matthew stared across the table into Greathouse's eyes as the man continued eating. "You can't actually be serious about hiring Zed."

"I'm absolutely serious. And as I have the authority from Katherine to make decisions in her absence, I intend to put things into motion right away."

"Things into motion? What does that mean?"

Greathouse finished all but a last bite of the sausage, which he obviously intended to savor when he'd gone through his corncakes. "First, the agency has to arrange to buy him from McCaggers."

"To buy him?"

"Yes, that's what I said. I swear, Matthew! Aren't you getting enough sleep? Don't things get into your head the first time these days?" Greathouse gave a wicked little grin. "Oh, ho! You're up late tripping the moonlight with Grigsby's granddaughter, aren't you?"

"Absolutely not!"

"Well, you say one thing and your blush says another."

"Berry and I are friends," Matthew said, in what he realized was a very tight and careful voice. "That's all."

Greathouse grunted. "I'd say two people running for their lives together across a vineyard either never want to see each other again or become more than friends. But I'm glad you brought her up."

"Me? I didn't bring her up!" For emphasis, he crunched his teeth down on a piece of the cracknel.

"She figures in my plan," Greathouse said. "I want to buy Zed from McCaggers, and I want to petition Lord Cornbury for a writ declaring Zed a freed man."

"A free-" Matthew stopped himself, for surely he did feel a bit thick-headed today. "And I suppose McCaggers will gladly sell you the slave he depends upon to do such a vital work?"

"I haven't yet approached McCaggers with this idea. Now bear with me." He chewed down the last bite of sausage, and again he reached for the tea. When that didn't do the trick, he plucked up Matthew's cider and drank half of it. "That jingo business you went out on. Walking into that den of thieves, and casting yourself as a foppish gambler. Well, the foppish part was true enough, but you really put yourself in danger there, Matthew, and don't pretend you didn't. If I'd known you were accepting a task like that, I'd have gone with you."

"You were fully occupied elsewhere," Matthew said, referring to the problem of Dr. Coffin that had taken Greathouse across the river to New Jersey. "And as I interpret the scope of my profession, I am free to accept or reject clients without your approval."

"Exactly so. Which is why you need someone to watch your back. I paid McCaggers a fee to allow Zed to dress up in the suit I bought for him and to come to the Cock'a'tail. I told him Zed would be in no danger, which is true when you consider what he can do."

"But you didn't know it was true. He had yet to prove himself." Matthew returned to the statement that had caused him to cease crunching his cracknell. "Someone to watch my back? You mean Zed would be my bodyguard?"

"Don't fly off the handle, now. Just listen. Do you know what instructions I asked McCaggers to give Zed last night? To protect the both of us, and to protect himself. I was ready to reach in if anything went wrong."

"Yes," Matthew said, with a nod. "That reach of yours almost got your hand chopped off."

"Everybody knows about that axe Skelly keeps behind the bar! I'm not stupid, Matthew!"

"Neither am I," came the calm but heated response. "Nor do I need a bodyguard. Hasn't it occurred to you that being in the company of a slave might cause more trouble than simply walking into a place-a den of thieves, as you say-and relying on your wits to resolve the problem? And I appreciate the fact that Zed is fearless. An admirable quality, I'm sure. But sometimes fearless and careless walk hand-in-hand."

"Yes, and sometimes smart and stubborn walk ass-in-hand, too!" said Greathouse. It was hard to tell whether it was anger or sausages flaming his cheeks, but for a few seconds a red glint lingered deep in the man's eyes; it was the same sort of warning Matthew occasionally saw when they were at rapier practice and Greathouse forgot where he was, placing himself mentally for a dangerous passing moment on the fields of war and the alleyways of intrigue that had both seasoned and scarred him. In those times, Matthew counted himself lucky not to be skewered, for though he was becoming more accomplished at defending his skin he would never be more than an amateur swordsman. Matthew said nothing. He cast his gaze aside and drank some cider, waiting for the older warrior to return from the bloodied corridors.

Greathouse worked his knuckles. His fists are already big enough, Matthew thought.

"Katherine has great hopes for you," Greathouse said, in a quieter tone of conciliation. "I absolutely agree that there should be no boundaries on what clients you accept or reject. And certainly, as she told you, this can be a dangerous-and potentially fatal-profession." He paused, still working his knuckles. It took him a moment to say what he was really getting at. "I can't be with you all the time, and I'd hate for your gravestone to have the year 1702 marked on it."

"I don't need a-" Matthew abruptly stopped speaking. He felt a darkness coming up around him, like a black cloak here amid these oblivious breakfast patrons of Sally Almond's. He knew this darkness very well. It was a fear that came on him without warning, made his heart beat harder and raised pinpricks of sweat at his temples. It had to do with a small white card marked with a bloody fingerprint. The card was in the writing desk in his home, what used to be the dairyhouse behind Marmaduke Grigsby's abode. Of this card, which had been delivered to his door by an unknown prowler after his adventure involving the Queen of Bedlam, Matthew had said nothing to any other person. He didn't wish Berry to know, and certainly not her grandfather with his ready quill and ink-stained fingers. Though Matthew had almost told Greathouse on several occasions he'd decided to close his mouth and shrug the darkness off as best he could. Which at times was a formidable task.

The card was a death-threat. No, not a threat. A promise. It was the same type of card that had been delivered to Richard Herrald, Greathouse's own half-brother, and after seven years the promise came true with his hideous murder. It was the same type of card that had been delivered to Magistrate Nathaniel Powers, whom Matthew had clerked for and who had brought Matthew and Katherine Herrald together. The death promise yet lingered over Powers, who had left New York with his family during the summer and gone to the Carolina colony to help his brother Durham manage Lord Kent's tobacco plantation.

It was a promise of death, this year or next, or the next year or the one after that. When this card was marked with a bloody fingerprint and sent to its victim, there could be no escape from the hand of Professor-

"Are you going to eat your rockahominy?" Greathouse asked. "It's lousy when it's cold."

Matthew shook his head, and Greathouse took the bowl.

After a moment during which the great man nearly cleaned all the rockahominy out of the bowl with four swipes of a spoon, Matthew's darkness subsided as it always did. His heartbeat returned to normal, the little pricklings of sweat evaporated and he sat calmly, with a blank expression on his face. No one was ever the wiser about how close they might be sitting to a young man who felt a horrific death chasing him down step after step, in a pursuit that might go on for years or might end with a blade to the back on the Broad Way, this very evening.

"Where are you?"

Matthew blinked. Greathouse pushed the bowl aside. "You went somewhere," he said. "Any address that I might know?"

"I was thinking about Zed," Matthew told him, and managed to make it sound convincing.

"Think all you like," came the quick reply, "but I've made the decision. It is absurd for a man of Zed's talent to be limited to hauling corpses around. I tell you, I've seen a lot of slaves but I've never seen a Ga in slavery before, and if there's a chance I can buy him from McCaggers, you can be sure I'm going to make the offer."

"And then go about setting him free?"

"Exactly. As was pointed out last night, it's against the law for slaves to enter taverns. What good would Zed be to us, if he couldn't enter where by necessity he might need to go?" Greathouse began to fish in a pocket for his money. "Besides, I don't like the idea of keeping a slave. It's against my religion. So, since there are several freedmen in New York, including the barber Micah Reynaud, there is a precedent to be followed. Put your money up, I'll call Evelyn over." He raised a hand for the waitress and the bill.

"A precedent, yes," Matthew agreed, "but every slave granted manumission was so approved before Lord Cornbury came. I'm wondering if he can be induced to sign a writ."

"First things first. Put your money up. You're done, aren't you?"

Matthew's hesitation spoke volumes, and Greathouse leaned back in his chair with a whuff of exhaled breath. "Don't tell me you have no money. Again."

"I won't, then." Matthew almost shrugged but he decided it would be risking Greathouse's wrath, which was not pretty.

"I shouldn't stand for you," Greathouse said as Evelyn came to the table. "This will be the third time in a week." He smiled tightly at the waitress as he took the bill, looked it over and paid her the money. "Thank you, dear," he told her. "Don't take any wooden duits."

She gave that little bell-like laugh and went about her business.

"You're spending too much on your damned clothes," Greathouse said, standing up from his chair. "What's got your money now? Those new boots?"

Matthew also stood up and retrieved his tricorn from its hook. "I've had expenses." The boots were to be paid off in four installments. He was half paid on his most recent suit, and still owed money on some shirts from Benjamin Owles. But they were such fine shirts, in chalk white and bird's-egg blue with frills on the front and cuffs. Again, the latest fashion as worn by young men of means. Why should I not have them, he thought, if I wish to make a good impression!

"Your business is your business," Greathouse said as they walked through the tavern toward the door. "Until it starts taking money out of my pocket. I'm keeping count of all this, you know."

They were nearly at the door when a middle-aged woman with thickly-curled gray hair under a purple hat and an exuberant, sharp-nosed face rose from the table she shared with two other ladies to catch Matthew's sleeve. "Oh, Mr. Corbett! A word, please!"

"Yes, madam?" He knew Mrs. Iris Garrow, wife of Stephen Garrow the Duke Street horn merchant.

"I wanted to ask if you might sign another copy of the Earwig for me, at your convenience? Sorry to say, Stephen accidentally used the first copy I had to kill a cockroach, and I've boxed his ears for it!"

"I'll be glad to, madam."

"Any new adventures to report?" breathlessly asked one of the other ladies, Anna Whitakker by name and wife to the Dock Ward alderman.

"Wo," Greathouse answered, with enough force to shake the cups of tea on their table. He grasped Matthew's elbow and pushed him out the door. "Good morning to you!"

Outside on Nassau Street, in the cool breeze with the silver sunlight beaming down, Matthew reflected that one might be a celebrity one day and the next have cockroach entrails smeared across one's name. The better to wear nice clothes, hold your head up high and luxuriate in fame, while it lasted.

"There's one more thing," Greathouse told him, stopping before they'd moved very far from Sally Almond's door. "I wish to know the extent of Zed's intelligence. How much he can grasp of English, for instance. How quickly he might be taught. You can help me."

"Help you how?" Matthew instantly knew he was going to regret asking.

"You know a teacher," Greathouse answered. When Matthew didn't immediately respond, he prodded: "Who helps Headmaster Brown at the school."

Berry Grigsby, of course. Matthew stepped aside to get out of the way of a passing wagon that pulled a buff-colored bull to market.

"I want her opinion. Bring yourself and your lady friend to City Hall at four o'clock. Come up to McCaggers' attic."

"Oh, she'll love that!" Matthew could picture Berry up in that attic, where McCaggers kept his skeletons and grisly relics of the coroner's craft. She'd be out of there like a cannonball shot from a twelve-pounder.

"She doesn't have to love it, and neither do you. Just be there." Greathouse narrowed his eyes and looked north along Nassau. "I have an errand to run, and it may take me awhile. I presume you have something to do today that doesn't require the risk of your life?"

"I'll find something." There were always the detailed reports of past cases that Matthew was scribing. Once a clerk, always so.

"Four o'clock, then," said Greathouse, and began to stride north along the street, against the morning traffic.

Matthew watched him go. I have an errand to run. Something was up. Greathouse was on the hunt. Matthew could almost see him sniffing the air. He was in his element, a wolf among sheep. On a case, was he? Who was the client? If so, he was keepi ng it a secret from Matthew. Well, so was Matthew keepi ng a secret. Two secrets, really: the blood card and the amount of debt he was carrying.

A third secret, as well.

Your lady friend, Greathouse had said.

Would that it were more, Matthew thought. But in his situation, in his dangerous profession, with the blood card laid upon him

Lady friend would have to do.

When he'd watched Greathouse out of sight, Matthew turned south along Nassau. He walked toward Number Seven Stone Street, where he would spend the morning scribing in his journal and from time to time pausing to mark what might have been the faint laughter of distant ghosts.

Four

Clouds moved across the blue sky, and the sunlight shone down upon villages and hills daubed with red, gold and copper. As the day progressed, so did the affairs of New York. A ship with its white sails flying came in past Oyster Island to make fast at the Great Dock. Higglers selling from their pushcarts a variety of items including sweetmeats, crackling skins and roasted chestnuts did a lively business, drawing an audience for their wares with young girls who danced to the bang and rattle of tambourines. A mule decided to show its force of will as it hauled a brickwagon along the Broad Way, and its subsequent stubborn immobility caused a traffic jam that frayed tempers and set four men to fighting until buckets of water poured on their heads cooled their enthusiasm. A group of Iroquois who had come to town to sell deerskins watched this entertainment solemnly but laughed behind their hands.

Several women and the occasional man visited the cemetery that stood behind a black iron fence alongside Trinity Church. There in the shade of the yellow trees, a flower or a quiet word was delivered to a loved one who had journeyed on from this earthly vale. Not much time was taken to linger here, however, for all knew that God accepted the worthy pilgrims with open arms, and life indeed was for the living.

Fishing boats in the rivers pulled up nets shimmering with striped bass, shad, flounder and snapper. The ferry between Van Dam's shipyard on King Street and the landing over the Hudson in Weehawken was always active for travelers and traders, who often found that the winds or currents could make even such a simple trip a three-hour adventure.

Across the city the multitudinous fires of commerce-be they from blacksmith's furnaces or tallow chandler's pots-burned brightly all the day, sending their signatures of smoke up through a mason's delight of chimneys. Closer to earth, workmen labored at new buildings that showed the northward progress of civilization. The boom of mallets and scrape of sawblades seemed never ceasing, and caused several of the eldest Dutch residents to recall the quiet of the good old days.

Of particular interest was the fact that the new mayor, Phillip French, was a solid, foursquare individual whose aim was to put his shoulder to the wheel and get more of the city's streets paved with cobblestones; this enterprise, too, was directed northward past Wall Street, but as it cost money from the treasury, the task was being currently stalled in paperwork by Governor Lord Cornbury, who was seldom seen in public these days outside the walls of his mansion in Fort William Henry.

All these events were of the common clay of New York. In one form or fashion, they were repeated as surely as dawn and dusk. But one event happening this afternoon, at four o'clock by Matthew's silver watch, had never before taken place: the ascent of Berry Grigsby up a narrow set of stairs in City Hall, toward Ashton McCaggers' realm in the attic above.

"Careful," Matthew said lest she lose her footing, but with an-other step it was he who stumbled behind Berry and found himself grasping a handful of her skirt to prevent a fall.

"Excuse you," she told him crisply, and pulled her skirt free at the same time as his hand flew away like a bird that had landed on a griddlecake iron. Then she gathered her grace and continued up the rest of the steps, where she came to the door at the top. She glanced back at him, he nodded, and she knocked at the door just as he'd instructed.

These days their relationship was, as a problem-solver might say, complicated. It was known to both of them that her grandfather had invited Berry to come from England in order to find her not necessarily a position, but a proposition. Up at the zenith of the list of eligible marriage candidates, at least in Marmaduke's conniving mind, was a certain citizen of New York named Corbett, and thus had Matthew been invited to make the dairyhouse his own miniature mansion, and to enjoy meals and companionship with the Grigsby clan, they being only a few steps from his own front door. Just showher around the town a little, Marmaduke had urged. Escort her to a dance or two. Would that kill you?