In Dominic Flandry finds friendship, maybe even love, after many years of being totally alone.

After , Flandry’s life stood in ruins. His Emperor, unbeknownst to him at the time, was dead; his sons were incompetent. His love was dead; his son was dead; he didn’t believe in his job any longer, and he’d taken out his biggest adversary.

So, what was left? This book shows the answer: plenty.

The younger son of Hans Molitor now holds the throne in his incompetent grasp, and worse, does not like Flandry. So, although Flandry is now a Vice-Admiral and commands much respect, he isn’t thrown too many assignments. On the other hand, he is able to make his own schedule, so when Miriam Abrams, daughter of mentor Max Abrams (his superior in ), manages to get to him to point out a major problem on Ramnau, he leaves.

Once again, he finds intrigue and lots of it, problems, and pain. But unlike , Flandry this time finds more while he’s solving the mystery. He and Abrams reach an understanding, and more or less pair off by the end of the book. He also helps solve her problem, take out a would-be Emperor candidate, and rehabilitate his image with Emperor Gerhardt (the younger son of Hans Molitor) in the process, so it’s definitely not a wasted trip.

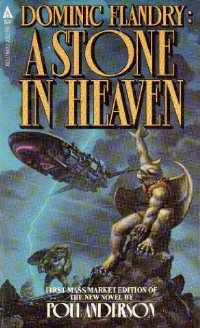

A Stone in Heaven

by Poul Anderson

I

Through time beyond knowing, the Kulembarach clan had ranged those lands which reach south of Lake Roan and east of the Kiiong River. The Forebear was said to have brought her family up from the Ringdales while the Ice was still withdrawing beyond the Guardian Mountains. Her descendants were there on the territory she took when traders from West-Oversea brought in the arts of ironworking and writing. They were old in possession when the first Seekers of Wisdom arose, and no few of them joined the College as generations passed. They were many and powerful when the long-slumbering fires in Mount Gungnor awoke again, and the Golden Tide flowed forth to enrich this whole country, and the clans together established the Lords of the Volcano. They were foremost in welcoming arid dealing with the strangers from the stars.

But about that time, the Ice began returning, and now the folk of Kulembarach were in as ill a plight as any of their neighbors.

Yewwl had gone on a long hunt with her husband Robreng and their three youngest children, Ngao, Ych, and little Ungn. That was only partly to get food, when the ranchlands could no more support enough livestock. It was also to get away, move about, unleash some of their rage against the fates upon game animals. Besides, her oath-sister Banner was eager to learn how regions distant from Wainwright Station were changed by cold and snow, and Yewwl was glad to oblige.

The family rode east for an afternoon and most of the following night. Though they did not hurry, and often stopped to give chase or to rest, that much travel took them a great ways, to one of the horn-topped menhirs which marked the territorial border of the Arrohdzaroch clan. Scarcity of meat would have made trespass dangerous as well as wrong. Yewwl turned off in a northwesterly direction.

“We will go home by way of the Shrine,” she explained to the others—and to Banner, who saw and heard and even felt what she did, through the collar around her neck. Had she wished to address the human unheard by anybody else, she would have formed the words voicelessly, down in her throat.

The alien tone never came to any hearing but Yewwl’s; Banner had said the sound went in through her skull. Eighteen years had taught Yewwl to recognize trouble in it: “I’ve seen pictures lately, taken from moon-height. You would not like what you found there, dear.”

Fur bristled, vanes spread and rippled, in sign of defiance. “I understand that. Shall the Ice keep me from my Forebear?” Anger died out. For Banner alone, Yewwl added softly, “And those with me hope for a token from her—an oracular dream, perhaps. And … I may be an unbeliever in such things, because of you, but I myself can nonetheless draw strength from them.”

Her band rode on. Night faded into hours of slowly brightening twilight. The storminess common around dawn and sunset did not come. Instead was eerie quiet under a moon and a half. The nullfire hereabouts did not grow tall, as out on the veldt, but formed a thick turf, hoarfrost-white, that muffled the hoofbeats of the onsars. Small crepuscular creatures were abroad, darters, scuttlers, light-flashers, and the chill was softened by a fragrance of nightwort, but life had grown scant since Yewwl and Robreng were young. They felt how silence starkened the desolation, and welcomed a wind that sprang up near morning, though it bit them to the bone and made stands of spearcane rattle like skeletons.

The sun rose at last. For a while it was a red step pyramid, far and far on the blurry horizon. The sky was opalescent. Below, land rolled steeply upward, cresting in a thousand-meter peak where snow and ice flushed in the early light. That burden spilled down the slopes and across the hills, broken here and there by a crag, a boulder, a tawny patch of uncovered nullfire, a tree—brightcrown or saw-frond—which the cold had slain. A flyer hovered aloft, wings dark against a squat mass of clouds. Yewwl didn’t recognize its kind. Strange things from beyond the Guardian Range were moving in with the freeze.

Ungn, her infant, stirred and mewed in her pouch. Her belly muscles seemed to glow with it. She might have stopped and dismounted to feed him, but a ruddy canyon and a tarn gone steel-hard told her through memory how near she was to her goal. She jabbed foot-claws at her onsar’s extensors and the beast stepped up its pace from a walk to a shamble, as if realizing, weary though it was and rapidly though the air was thinning, that it could soon rest. Yewwl reached into a saddlebag, took forth a strip of dried meat, swallowed a part for herself and chewed the remainder into pulp. Meanwhile she had lifted Ungn into her arms and cuddled him. Her vanes she folded around her front to give the beloved mite shelter from the whining, seeking wind.

Ych rode ahead. The sun entered heaven fully, became round and dazzling, gilded his pelt and sent light aflow over the vanes that he spread in sheer eagerness. He was nearly grown, lithe, handsome; no ruinous weather could dim the pride of his youth. His sister Ngao, his junior by three years, rode behind, leading several pack animals which bore camp gear and the smoked spoils of the hunt. She was slightly built and quiet, but Yewwl knew she was going to become a real beauty. Let fate be kind to her!

Having well masticated the food, the mother brought her lips around her baby’s and, with the help of her tongue, fed him. He gurgled and went back to sleep. She imagined him doing it happily, but knew that was mere imagination. Just six days old—or fourteen, if you counted from his begetting—he was as yet tiny and unshapen. His eyes wouldn’t open for another four or five days, and he wouldn’t be crawling around on his own till almost half a year after that.

Robreng drew alongside. “Here,” Yewwl said. “You take him a while.” She handed Ungn over for her husband to tuck in his pouch. With a close look: “What’s wrong?”

The tautness of his vane-ribs, the quivering along their surfaces, the backward slant of his ears, everything about him cried unease. He need but say: “I sense grief before us.”

Yewwl lifted her right thigh to bring within reach the knife sheathed there. (Strapped to the left was a purse for flint, steel, tinderbox, and other such objects.) “Beasts?” Veldt lopers seldom attacked folk, but a pack of them—or some different kind of carnivore—might have been driven desperate by hunger. “Invaders?” The nightmare which never ended was of being overrun by foreigners whom starvation had forced out of their proper territory.

His muzzle wrinkled, baring fangs, in a negative. “Not those, as far as I can tell. But things feel wrong here.”

In twenty years of marriage, she had learned to trust his judgment nearly as much as her own. While a bachelor, he had fared widely around, even spending two seasons north of the Guardians to hunt in the untenanted barrens there. He it was who had argued, when last the clan leaders met before the Lord of the Volcano, that this country need not be abandoned. Orchards and grazing would wither, ranching come to an end, but creatures native to the cold lands would move in; the Golden Tide would make them abundant; folk could live entirely off the chase, without falling back into savagery. Of course, the transition would take lifetimes, and those would be grim, but surely the star-beings would help …

Thus it was daunting to see him shaken. “What do you mark, then?” Yewwl asked.

“I am not sure,” Robreng confessed. “It’s been too long since I was in snow-decked uplands. Once my partner went down in a deep drift and was stuck, but we got him out. Our guide took us well clear of high hillsides, but I can’t recall why. He had few words of our language.”

“Banner,” Yewwl said aloud, each word a fog-puff, “do you know of any danger we might be in?”

Across hundreds of kilometers, the secret voice replied, “No. That doesn’t mean there is none, you realize. Your world is so different from mine—and so few humans have visited it, really, in all these centuries—and now everything is changing so fast—How I wish I could warn you.”

“Well, thank you, my oath-sister.” Yewwl told Robreng what she had heard. Decision came. “I think I grasp what the matter is. It’s within us—in me too. I remember how these parts were fair and alive when we were children; we remember caretakers, pilgrims, offerings and feasts and Oneness. Today we come back and find all gone dead and hollow. No wonder if dread arises.” She straightened in her saddle. “Strike it down! Onward!”

Ych crossed a root of the mountain and dropped out of sight. In a moment, his shout rang over ice and rock. He had spied the Shrine.

His kin urged their onsars to speed, from shamble to swing. Four massive legs went to and fro; sparks flew where hoofs smote rock. Between, the thick extensors did more than help support the body; they gripped, pulled, shoved, let go, seized hold afresh on the ground. Aft of the hump where saddles or packs were, dorsal fins wagged, black triangles as high as a rider’s head. Sweat gleamed on gray skin, sparse brown hair, big ears. Breath went loud, harsh, in and out of muzzles. Thews pulsed to the rocking motion.

Yewwl topped the ridge and glanced aloft. Sharply through the thin, clear air of the heights, she saw her goal.

The tomb of Kulembarach stood on a ledge a third of the way up the mountainside. It was a dolmen, rough granite slabs chiseled out of some quarry, somehow brought here and fitted together, in an age before iron. But around it, generation after generation had built terraces, raised houses and statues, nurtured exquisite gardens where fountains played and flutes replied. Here had been gathered the finest works of the clan and the best that traders abroad could bring home: pictures, jewelry, weavings, books, such awesome memorabilia as the Sword Which Held the Bridge, Amarao’s cup, the skulls of the Seven Heroes, the quern of Gro the Healer.

Today—

Nearing, Yewwl could barely make out the balustrades of the terraces, overflowed by snow. Frost had shattered several, and brought low a number of the sculptures which elsewhere stood forlorn as the stricken trees. When the last caretakers must depart or die, cold had numbed them into carelessness, fire had escaped a hearth, nothing but blackened stonework was left of the delicately carpentered buildings. Bereft of its wooden gate, the arch before the tomb gaped with horrible emptiness.

The onsars turned onto the road which led thither. It ascended too abruptly to be much drifted over, and the paving blocks were not yet sundered and tumbled and split, except in a few places. They rang under hoofs, answering the wind that wailed and bit and scattered a haze of dry ice crystals to shatter what sunlight came over the eastern shoulder into this darkling passage. Beyond the Shrine grounds the mountain rose steeper yet for a space, in a talus slope which clingplant had once made colorful but which was now only jagged and bleak. Above it, where the slope was easier, the snowpack began, that went on over the peak. It formed a white cliff, meters tall, mysteriously blue-shadowed.

Nonetheless … amidst the ruins, rearing over banks, upbearing what had fallen upon it during the night, the dolmen remained, foursquare. Kulem-barach abided, at watch over her people. To those who sought her, she would still give dreams and luck … or, at least, the strength that came from remembering that she had prevailed in her day, and her blood endured … Yewwl’s pulse thuttered.

Ych was already there. When no keepers were left, that had earned him the right to greet the Forebear on behalf of his party. He unslung the bugle at his saddlebow and put it to his lips. Riding around and around the tomb, he challenged desolation with the hunting call of his mother.

The snowcliff stirred.

A mighty wind rushed downward from it, smote like hammers, roared like thunder. Statues and tree boles toppled before the blow.

Earth shuddered. Hill-huge masses broke from the sliding precipice, flew, struck, smashed and buried what they hit. Behind them came the doom-fall itself.

Yewwl never remembered what happened. Surely she vaulted to a stance on her saddle and sprang from it, spreading her vanes, as if she were about to attack game on an open plain. Surely she went gliding, and she did not come down soon enough to be engulfed. Therefore surely she caught updrafts, rode the buffeting airs that the slide hurled before it, crashed bruised and bleeding but not truly wounded in her body, down onto a ridge above the path of destruction.

What she knew, at first, was nothing but a noise that should break the world apart, blindness, choked throat, tumbling well-nigh helpless—being tossed against raw rock and clawing herself fast while chaos raged—finally, silence, but for the ringing in her ears; and pain; and dazedly rising to stare.

Where the Shrine had been, the road, the onsars, her companions: snow filled the vale, nearly as high as she was. A mist of crystals swallowed vision within fifty meters; it would be hours in settling. Suddenly there was no wind, as if that also had been seized and overwhelmed.

“Robreng!” Yewwl screamed. “Ungn! Ych! Ngao!”

It took her hours of crawling about and shouting to become certain that none of them had escaped.

By then she was at the bottom of the slide, in the foothills under the mountain.

She staggered away. She would not rest before she must, before flesh and bones fell down in a heap. And then she would not be long a-swoon; she would rise again, again she would howl and snarl her sorrow, she would hunt and kill whatever stirred in the waste, because she could not kill the thing that had slain her darlings.

In Wainwright Station, Miriam Abrams slapped the switch of her multitransceiver, tore herself free of every connection to it, and surged from her chair. A calculator happened to be lying on the console shelf. She dashed it to the floor. It didn’t break as she wanted, but it skittered. “God damn them!” she yelled. “God damn them to the deepest hole in hell!”

The single person in the room with her was Ivan Polevoy, electronician, who had had some tinkering to do on a different piece of equipment. He had seen Abrams rapt in her rapport with the native, but not what was happening, for side panels effectively blocked his view of the video screen. The woman maintained that her relationship was sufficient invasion of privacy—though she admitted “privacy” was a notion hard to apply between unlike species. She herself spent incredible lengths of time following the life of her subject. The Ramnuan obviously didn’t mind, no matter how intimate events became. Possibly she’d not mind if other humans observed too. However, Abrams had made it plain from the start, a couple of decades ago, that she alone would receive the raw data. The reports she prepared on that basis were detailed, insightful contributions to xenology; but nobody else knew how much she chose to leave out.

The former chief of planetside operations had supported her in that policy. It was doubtless prudent, when little was known about Ramnuan psychology. Nowadays Abrams was the chief, so the staff didn’t object either. Besides, their own jobs or projects kept them amply busy, undermanned as the place was.

Hence Polevoy had to ask in surprise: “Damn who? What’s wrong, Banner?”

It was as if her nickname calmed her a little. Yet she had borne it for many years. Translated from the local language—wherein it derived from the flag which identified Wainwright Station at a distance to travelers—it had practically supplanted “Miriam,” even in her mind. At this hour, it seemed to tell her that dear ones died, but the race lived on.

Regardless, tears glistened on her lashes. The hand shook that fished a cigarette from a tunic pocket, struck it, and brought it to her mouth. Cheeks caved in with the violence of her smoking. Her voice was hoarse rather than husky, and wavered.

“Avalanche. Wiped out Yewwl’s whole family … and, oh, God, the Shrine, the heart of her clan’s history—like wiping out Jerusalem—” A fist beat itself unmercifully against the console. “I should have guessed. But … no experience … I’m from Dayan, you know, warm, dry, no snow anywhere, and I’ve just been a visitor on worlds like Terra—” Her lips drew wide, her eyes squinched nearly shut. “If I’d thought! That much snowpack, and seven Terrestrial gravities to accelerate it—Yewwl, Yewwl, I’m sorry.”

“Why, that’s terrible,” Polevoy said. After a pause: “Your subject, she’s alive?”

Abrams jerked a nod. “Yes. With nothing to ride, no tent or supplies or tools or anything but what she’s got on her person, and doubtless not a soul for a hundred kilometers around.”

“Well, we’d better send a gravsled for her. It can home on her transceiver, can’t it?” Polevoy was fairly new here.

“Sure, sure. Not right away, though. Don’t you know what grief usually does to a Ramnuan? It’s apt to drive him or her berserk.” Abrams spoke in rough chunks of phrase. “Coping with that is a problem which every society on this planet has had to solve, one way or another. Maybe that’s a main reason why they’ve never had wars—plenty of individual fights, but no wars, no armies, therefore no states—A soldier who lost his buddy would run amok.” Laughter rattled from her. “Too bad we humans don’t have the same trait. We wouldn’t be cobwebbed into our Terran Empire then, would we?” She stubbed out the cigarette, viciously, and started the next. “We’ll go fetch Yewwl when she’s worked off the worst of what’s in her, if she lives through it. Sometime this afternoon.” That would be several standard days hence. “Meanwhile, I can be preparing to take on the wretched Empire.”

Shocked, Polevoy could merely say, “I beg your pardon?”

Abrams slumped. She turned from him and stared out a viewscreen. It gave a broad overlook across the locality. On her right, the Kiiong River flowed seaward, more rapidly than any stream on Terra or Dayan would have gone through a bed as level as was here. Spray off rocks dashed brilliant above water made gray-green by glacial flour. Sonic receptors brought in a booming of great slow airs under more than thirty bars of pressure. Beyond the river was forest: low, thick trunks from which slender branches swayed, upheld by big leaves shaped like parachutes, surrounded by yellowish shrubs.

To her left, eastward, chanced to be rare clarity. Dun pyrasphale rippled across twelve kilometers to Ramnu’s horizon. Trees and canebrakes broke the sameness of that veldt; a kopje reared distance-blued; clouds cruised above, curiously flattened. A small herd of grazers wandered about, under guard of a mounted native. A score of flying creatures were aloft. When Abrams first arrived, this country had swarmed with life.

Overhead, the sky was milky. Niku, the sun, appearing two-thirds as wide as Sol seen from Terra, cast amber light; a frost halo circled it. Diris, the innermost moon, glimmered pale toward the west. It would not set until Ramnu’s long day had become darkness.

“Another ice age on its way,” Abrams mumbled. “The curse of this world. And we could stop it and all its kind. Whatever becomes of us and our Empire, we could be remembered as saviors, redeemers, for the next million years. But the Duke will not listen. And now Yewwl’s people are dead.”

“Uh,” Polevoy ventured, “uh, doesn’t she have a couple of children who’re adult, married?”

“Yes. And they have children, who may well not survive what’s coming down from the north,” Abrams said. “Meanwhile she’s lost her husband, her two youngsters, the last baby she’ll ever bear; her clan has lost its Jerusalem; and none of that needed to happen.” Tendons stood forth in her neck. “None of it! But the Grand Duke of Hermes would never listen to me!”

After more silence, she straightened, turned around, said quite calmly: “Well, I’m done with him. This has been the last thing necessary to decide me. I’m going to leave pretty soon, Ivan. Leave for Terra itself, and appeal for help to the very top.”

Polevoy choked. “The Emperor?”

Abrams grinned in gallows mirth. “No, hardly him. Not at the start, anyhow. But … have you ever perchance heard of Admiral Flandry?”

II

First she must go to the Maian System, nineteen light-years off, a journey of four standard days in the poky little starcraft belonging to the Ramnu Research Foundation. The pilot bade her farewell at Williams Field on Hermes and went into Starfall to see what fleshpots he could find before returning. Banner also sought the planet’s chief city, but with less frivolous intentions. Mainly she wanted shelter, and not from the mild climate.

She had cut her schedule as close as feasible. The liner Queen of Apollo would depart for Sol in fifty hours. Through Sten Runeberg, to whom she had sent a letter, she had a ticket. However, coming as she did from a primitive world of basically terrestroid biochemistry, she must get a checkup at a clinic licensed to renew her medical certificate. That was a ridiculous formality—even had she been exposed in shirtsleeves to Ramnu, no germ there could have lived a minute in her bloodstream—but the bureaucrats of Terra were adamant unless you held rank or title. Equally absurd, she thought, was the quasi-necessity of updating her wardrobe. She didn’t think Flandry would care if she looked provincial. Yet others would, and her mission was difficult enough without her being at a psychological disadvantage.

Therefore she sallied forth on the morning after she arrived at the Runebergs’ town house, and didn’t come back, her tasks completed, till sundown. “You must be exhausted, fairling,” said her host. “How about a drink before dinner?”

Fairling—The mild Hermetian endearment had taken on a special meaning for the two of them, when he was in charge of industrial operations at Ramnu and they had been lovers whenever they could steal time together. The three-year relationship had ended five years ago, with his inexplicable replacement by taciturn Nigel Broderick; it had never been deeply passionate; now he was married, and they had exchanged no more than smiles and glances during her stay, nor would they. Nonetheless, memory stabbed.

Runeberg’s wife was belated at her office. He, who had become a consulting engineer, had quit work early for his guest and put his child in charge of the governess. He mixed two martinis himself and led the way onto a balcony. “Pick a seat,” he invited, gesturing at a couple of loungers.

Banner stayed by the rail. “I’d forgotten how beautiful this is,” she whispered.

Dusk flowed across the quicksilver gleam of Daybreak Bay. The mansion stood on the southern slope of Pilgrim Hill, near the Palomino River. It commanded a view of the keeps above; of its own garden, fragrant with daleflower and roses, where a tilirra flew trilling and glowflies were blinking alight; of Riverside Common, stately with million-leaf and rainroof trees; of multitudinous old spires beyond and windows that’had begun to shine; of domes and towers across the stream, arrogantly radiant as if this were still that heyday of their world in which they had been raised. The air was barely cooled by a breeze and murmured only slightly of traffic. Heaven ranged from blue in the west to violet in the east. Antares was already visible, rising Venus-bright and ruby-red out of the Auroral Ocean.

“You should have come here more often,” Runeberg said.

“You know I could hardly drag myself away from my work, ever, and then mostly to visit my parents,” Banner replied. “Since Dad’s death—” She broke off.

The big blond man regarded her carefully. She stood profile to, so that he saw the curve of her nose below the high forehead, the set of her wide mouth and the jut of her chin and the long sweep of her throat down to the small bosom. Clad in a shimmerlyn gown—for practice at being a lady, she had said—she stood tall and slim, athletic despite the scattered silver in a shoulder-length light-brown mane. Then she turned around, briefly silhouetting a cheekbone ivory against the sky, and her eyes confronted his. They were perhaps her best feature, large and luminous green under dark brows.

“Yes,” he blurted, “you’ve let yourself get crazily wrapped up in those beings. Sometimes I’d find you slipping into styles of thought, emotion, that, well, that weren’t human. It must have gotten worse since I left. Come back, Miri.”

He disliked calling me Banner, she remembered. “You imply that involvement with an intelligent, feeling race was bad in the first place,” she said. “Why? On the whole, I’ve had a wonderful, fascinating, exciting life. And how else can we get to understand them? A different psychology, explored in depth … What can we not learn, also about ourselves?”

Runeberg sighed. “Who is really paying attention? Be honest. You’re studying one clutch of sophonts among countless thousands; and they’re barbarians, impoverished, insignificant. Their planet was always more interesting to science than they were, and it was investigated centuries back, in plenty of detail. Xenology is a dying discipline anyway. Every pure science is; we live in that kind of era. Why do you think your foundation is marginally funded? Hai-ah, it’d have been closed down before you were born, if Ramnu didn’t happen to have some value to Hermetian industry. You’ve sacrificed every heritage that was yours—for what, Miri?”

“We’ve wasted time on that battleground in the past,” she snapped. Her tone softened. “I don’t want to quarrel, Sten. You mean well, I know. From your viewpoint, I suppose you’re right.”

“I care about you, my very dear friend,” he said. And it hurt you from the start to learn what I’d lost, she did not answer aloud. My marriage—Already established in the profession when he took a fresh graduate from the Galactic Academy for his bride, Feodor Sumarokov had seen their appointments to Ramnu as a steppingstone to higher positions; when he left after three years, she would not. My true love—She had never wedded Jason Kamunya, because they wanted to do that back on Dayan where her parents were, and somehow they never found a time when so long an absence wouldn’t harmfully interrupt their research, and meanwhile they could live and work together … until that day in their fourth year when a stone falling from a height under seven gravities shattered his air helmet and head … My chance for children—Well, perhaps not yet. She was only forty-four. But not all the gero treatment known to man could stave off menopause for more than a decade, or add more than two or three to a lifespan; and where she was, she had had access to nothing but routine cell therapy. My home, my kindred, my whole civilization—

Ramnu is my home! Yewwl and her folk are my kin in everything but flesh. And what is Technic civilization worth any longer? Unless I can make it save my oath-sister’s world.

Banner smiled and reached out to stroke the man’s cheek. “Thank you for that,” she murmured. “And for a lot else.” Raising her glass: “Shalom.”

Rims clinked together. The liquor was cold and pungent on her tongue. She and he reclined facing each other. Twilight deepened.

“You completed your business today?” he inquired.

“Yes. Inconspicuously, I hope.”

He frowned. “You really are obsessive about secrecy, aren’t you?”

“Or forethoughtful.” Her voice wavered the least bit. “Sten, you did do your best to handle my reservation and such confidentially, didn’t you?”

“Of course, since you asked. I’m not sure why you did.”

“I explained. If the Duke knew, he might well decide to stop me. And he could, in a dozen different ways.”

“Why would he, though?”

Banner took a protracted sip. Her free hand fumbled in her sash pocket for a cigarette case. “He’s neutronium-solid set against any project to reverse the glaciation on Ramnu.”

“Hoy? … True, true, you complained to me, in person and afterward in those rare letters you sent, that he won’t consider Hermes making the effort.” Runeberg drew breath for an argument. “Maybe he is being ungenerous. We could afford it. But he may well deem—in fact, you’ve quoted him to me to that effect—that our duty to ourselves is overriding. Hermes isn’t poor, but it’s not the rich, powerful world it used to be, either, and we’re developing plenty of problems, both domestic and vis-a-vis the Imperium. I can understand how Duke Edwin may think an expensive undertaking for the sake of aliens who can never pay us back—how that might strain us dangerously, rouse protest, maybe even provoke an attempt at revolution.”

Banner started her smoke before she said bitterly, “Yes, he must feel insecure, yes, indeed. It’s not as if he belonged to the House of Tamarin, or as if constitutional government still existed here. His grandfather was the latest in a string of caudillos, and he himself eased his elder brother off the throne.”

“Now, wait,” Runeberg protested. “You realize I’m not too happy with him either. But he is doing heroic things for Hermes, and he does have ample popular support. If he has no Tamarin genes in him, he does carry a few Argolid ones, distantly, but from the Founder of the Empire just the same. It’s the Imperium that’s jeopardized its own right to rule—Hans Molitor seizing the crown by force—later robbing us of Mirkheim, to buy the goodwill of the money lords on Terra—” He checked himself. It was talk heard often nowadays, in private. But he didn’t want to speak anger this evening. Moreover, she was leaving tomorrow in hopes of getting help there.

“The point is,” he said, “why should the Duke mind having your project financed and organized from outside? He ought to welcome that. Most of the resources and labor could come from our economic sphere. We’d get nice jobs, profits, contacts, every sort of benefit.”

“I don’t know why he should object,” Banner admitted. “I do know he will, if he finds out. I’ve exchanged enough letters and tapes with his immediate staff. I’ve come in person, twice, to plead, and got private audiences both times. Oh, the responses were more or less courteous, but always absolutely negative; and meeting with him, I could sense outright hostility.”

Runeberg gulped from his drink before he ventured to say: “Are you sure you weren’t reading that into his manner? No offense, fairling, but you are not too well acquainted with humankind.”

“I’ve objective facts in addition, in full measure,” she retorted. “My last request was that he ask the Emperor to aid Ramnu. His answer, through an undersecretary, was that this would be politically inadvisable. I’m not too naive to recognize when I’m being fobbed off. Especially when the message closed by stating that they were tired of this business, and if I persisted in it I could be replaced. Edwin Cairncross is quite willing to use his influence on Terra to crush one obscure scientist!”

She drew hard on her cigarette, leaned forward, and continued: “That’s not the only clue. For instance, why were you discharged from General Enterprises? Everybody I talked to was astounded. You’d been doing outstanding work.”

“I was simply told ‘reorganization,’ ” he reminded her. “I did get handsome severance pay and testimonials. As near as I’ve been able to find out, somebody in a high position wanted Nigel Broderick to have my post. Bribery? Blackmail? Nepotism? Who knows?”

“Broderick’s been less and less cooperative with the Foundation,” she said. “And that in spite of his expanding operations on Ramnu as well as its moons. Though it’s impossible to learn exactly what the expansion amounts to. The time is past when my people or I could freely visit any of those installations.”

“Um-m, security precautions—There’s been a lot of restriction in the Protectorate, too, lately. These are uneasy years. If the Imperium breaks down again—which could give the Merseians a chance to strike—”

“What threat to security is a xenological research establishment? But we’re being denied adequate supplies, that we used to get as a matter of course from Dukeston and Elaveli. The pretexts are mighty thin, stuff like unspecified ‘technical difficulties.’ Sten, we’re being slowly strangled. The Duke wants us severely restricted in our activities on both Ramnu and Diris, if not out of there altogether. Why?”

Banner finished her cigarette and reopened the case.

“You smoke too much, Miri,” Runeberg said.

“And drink too little?” Her laugh clanked. “Very well, let’s assume my troubles have made me paranoid. What harm in keeping alert? If I return in force, maybe my questions will get answered.”

He raised his brows. “In force?”

“Oh, not literally. But with backing too powerful for a mere lord of a few planetary systems.”

“Whose backing?”

“Haven’t you heard me mention Admiral Flandry?”

“Ye-es, occasionally in conversation, I believe. I got the impression he is—was a friend of your father’s.”

“Dad was his first superior in action, during the Starkad affair,” she said proudly. “He got him started in Naval Intelligence. They kept in touch afterward. I met Flandry myself, as a girl, when he paid a visit to a base where Dad was stationed. I liked him, and he wouldn’t have stayed Dad’s friend if he weren’t a decent man at heart, no matter what he may have had to do in his career. He’ll receive a daughter of Max Abrams. And … he has the Emperor’s ear.”

She tossed down her cigarette case, raised her glass, and said almost cheerfully, “Come, let’s drink to my success, and then let’s hear more about what’s been happening to you, Sten, old dear.”

Night rolled westward across Greatland. Four hours after it had covered Starfall it reached Lythe, in the middle of the continent.

That estate of Edwin Cairncross, Grand Duke of Hermes, was among his most cherished achievements. Reclamation of the interior for human settlement had faltered a century ago, as the wealth and importance of the planet declined. Civil war had stopped it entirely, and it had not resumed at once after Hans Molitor battered the Empire back together. He, Cairncross, had seen an extinct shield volcano rising mightily above an arid steppe, and desired an eyrie on the heights. He had decreed that canals be driven, land be resculptured and planted, lovely ornithoids and big game be introduced, a town be founded down below and commerce make it prosper. The undertaking was minor compared to other works of his, but somehow, to him, Lythe symbolized the will to prevail, to conquer.

It was no sanctuary for fantasy, but a nucleus for renewed growth. From it he did considerable of his governing, through an electronic web that reached across the globe and beyond. An invitation to spend some days here could be portentous. This evening he had passed hours alone in his innermost office, hunched above the screen whose sealed circuits brought him information gathered by a bare dozen secret agents. They were the elite of their corps; they reported directly to him, and he decided if their nominal superiors would be told.

Now he must make a heavier choice than that. With a blind urge to draw strength from his land, he strode out of the room and through the antechambers.

Beyond, a sentry snapped a salute. Cairncross returned it as precisely. His years in the Imperial Navy had taught him that a leader is wise to give his underlings every courtesy due them. An aide sprang from a chair and inquired, “Sir?”

“I don’t want to be disturbed, Wyatt,” Cairncross said.

“Sir!”

Cairncross nodded and went on down the hall. Until new orders came, the lieutenant would make sure that nobody, not the Duchess herself, got near the Grand Duke.

A gravshaft brought Cairncross up onto a tower. He crossed its deck and halted at the battlement. That was pure ornamentation, but not useless; he had ordered it built because he wanted to feel affirmed in his kinship to Shi Huang Ti, Charlemagne, Suleiman the Magnificent, Pyotr the Great, every man who had ever been dominant on Terra.

Silence dwelt enormous. The fog of his breath caught the light of a crescent Sandalion; he savored the bracing chill that he inhaled. Vision winged across roofs, walls, hoar treetops, cliffs and crags, a misty shimmer of plains, finally the horizon. He raised his eyes and beheld stars in their thousands.

Antares burned brightest. Mogul was sufficiently near to rival it, an orange spark: Mogul, sun of Babur, the Protectorate. His gaze did not seek Olga, for in that constellation, invisible to him, was the black sun of Mirkheim; and he had no time on hand to think about regaining the treasure planet for Hermes. Sol was hidden too, by distance. But Sol—Terra—was ruler of the rest … He turned his glance from the Milky Way. Its iciness declared that the Empire was an incident upon certain attendants of a hundred thousand stars, lost in the outskirts of a galaxy which held more than a hundred billion. A man must ignore mockery.

Wryness: A man must also buckle down to practical details. What Cairncross had learned today demanded instant action.

The trouble was, he could not do the quick and simple thing. Abrams had been too wary. His fists knotted.

Thank God for giving him the foresight to have Sten Runeberg’s house bugged, after he’d gotten the man fired from Ramnu. Not that Runeberg had made trouble. He might have, though. The family was extensive and influential; Duchess Iva was a second cousin of Sten. And he had been at Ramnu, he had been close to Abrams, he had surely acquired ideas from her … and maybe worse ones afterward, since they did irregularly correspond and meet.

Nothing worth reporting had happened until today. But what finally came was a blow to the guts.

The witch outmaneuvered me, Cairncross thought. I have the self-confidence to realize that. She’d written to Runeberg in care of the spaceship he used in his business; no bug could escape the safety inspections there. She’d arrived unannounced and gone straight to his place. The ducal government lacked facilities to monitor every slightly distrusted site continuously; tapes were scanned at intervals. Given reasonable luck, Abrams would have been in and out of Hermes well before Cairncross knew.

She did chance to pick the wrong time slot. (That was partly because surveillance was programmed to intensify whenever a passenger liner was due in, until it had departed.) But she had anticipated the possibility. Runeberg and a couple of his spacemen were going to escort her tomorrow, not just onto the shuttle but to the Queen in orbit, and see her off. He had objected that that was needless, but to soothe her he had agreed. Meanwhile, his wife and several others knew about it all. There was no way, under these conditions, to arrange an abduction or assassination. Anything untoward would be too damnably suspicious, in a period when a degree of suspicion was already aimed at Cairncross.

Well, I’ve made my own contingency plans. I didn’t foresee this turn of events exactly, but—

Decision crystallized. Yes, I’ll go to Terra myself. My speedster can outrun her by days.

Cairncross made a fighting grin. Whatever came next should at least be interesting!

III

Vice Admiral Sir Dominic Flandry, Intelligence Corps, Imperial Terran Navy, maintained three retreats in different areas that he liked. None was as sybaritic as his home base in Archopolis, a part of which served him for an office. Apart of that, in turn, was austere, for times when he found it helpful to give such an impression of himself. Which room he used seldom mattered; ordinarily he did his business through computers, infotrieves, and eido-phone, with the latter set to show no background. Some people, though, must be received in person. A governing noble who wanted to see him privately was an obvious example.

This meant rising at an unsanctified hour—after a visitor had kept him awake past midnight—to review available data in advance of the appointment. The visitor had been warned she must go before breakfast, since he couldn’t afford the time for gallantries. Flandry left her drowsy warmth and a contrail of muttered curses behind him, groped his way to the gymnasium, and plunged. A dozen laps around the pool brought him to alertness. They failed to make the exercises which followed any fun. He had loathed calisthenics more in every successive year of his sixty-one. But they had given him a quickly responsive body in his youth, and it was still trim and tough beyond anything due to gero treatments.

At last he could shower. When he emerged, Chives proffered a Turkish towel and coffee royal. “Good morning, sir,” he greeted.

Flandry took the cup. “That phrase is a contradiction in terms,” he said. “How are you doing?”

“Quite well, thank you, sir.” Chives began to rub his master dry. He wasn’t as deft as erstwhile. He didn’t notice that he nearly caused the coffee to spill. Flandry kept silence. Had he, in this place, let anyone but Chives attend him, the Shalmuan’s heart would have cracked open.

Flandry regarded the short green form—something like a hairless human with a long tail, if you ignored countless differences in shapes and proportions of features—through eyes that veiled concern. This early, Chives wore merely a kilt. Wrinkles, skinniness, stiff movements were far too plain to sight. No research institution had ever considered developing the means to slow down aging in the folk of his backward world.

Well, if that were done, how many other sophont races would clamor for the same work on each of their wildly separate biochemistries? the man thought, for perhaps the thousandth sad time. I may have my valet-majordomo-cook-bodyguard-pilot-factotum-arbiter for a decade yet, if I’m lucky.

Chives finished and gave the towel a reassuringly vigorous snap. “I have laid out your formal uniform and decorations, sir,” he announced.

“Formal—one cut below court? And decorations? He’ll take me for a popinjay.”

“My impression of the Duke is otherwise, sir.”

“When did you get at his dossier? … Nevermind. No use arguing.”

“I suggest you be ready for breakfast in twenty minutes, sir. There will be a souffle.”

“Twenty minutes on the dot. Very good, Chives.” Flandry left.

As usual when it was unoccupied, the clothes were in a guestroom. Flandry draped them over his tall frame with the skill of a foppish lifetime. These days, he didn’t really care—had not since a lady died on Dennitza, fourteen years ago—but remained a fashion plate out of habit, and because it was expected of him. Deep-blue tunic, gold on collar and sleeves, nebula and star on either shoulder; scarlet sash; white iridon trousers bagged into half-boots of lustrous black beefleather; and the assorted ribbons, of course, each a brag about an exploit though most of the citations were recorded only in the secret files; and the Imperial sunburst, jewel-encrusted, hung from his neck, to proclaim him a member of the Order of Manuel, silliest boast of the lot—

Brushing his sleek iron-gray hair, he checked to make sure his last dash of beard inhibitor wasn’t wearing off. It wasn’t, but he decided to trim the mustache that had, thus far, stayed brown. The face behind hadn’t changed much either: high in the cheekbones, straight in the nose, cleft in the chin, relic of a period when everybody who could afford it got biosculped into comeliness. (The present generation scorned that; in many ways, these were puritanical times.) The eyes of changeable gray were more clear than they deserved to be after last night. The skin, lightly tanned, stayed firm, though lines ran over the brow, crow’s-feet beneath, deep furrows from nostrils to lips.

Yes, he thought a trifle smugly, we’re holding our own against the Old Man. A sudden, unexpected thrust brought a gasp. Why not? What’s his hurry? He’s hauled in Kossara and young Dominic and Hans and—how many more? I can be left to wait his convenience.

He rallied. Self-pity! First sign of senility? Squash it, fellow. You’ve got health, money, power, friends, women, interesting work that you can even claim is of some importance if you want to. Your breakfast is being prepared by none less than Chives—He glanced at his watch, whistled, and made haste to the dining room.

The Shalmuan, met him at the entrance. “Excuse me, sir,” he said, and reached up to adjust the sunburst on its ribbon before he seated his master and went to bring the food.

The weather bureau had decreed a fine spring day. Chives had therefore retracted the outer wall. Flowers, Terran and exotic, made the roof garden beyond into an explosion of colors and perfumes. A Cynthian yaoti perched bright-plumed on a bough of a blossoming orange tree and harped out of its throat. Everywhere around, towers soared heavenward in fluid grace; this quarter of the city went back two centuries, to when an inspired school of architecture had flourished. White clouds wandered through blue clarity; aircars sparkled in sunlight. A breeze brought coolness and a muted pulse of machines in the service of man. And here came the souffle.

Later was the first, the truly delicious cigarette, out in the garden beside a dancing fountain. What followed was less pleasant, namely, spadework. But all this had to be paid for somehow. Flandry could retire whenever he chose: to a modest income from pension and investments, and an early death from boredom. He preferred to stay in the second oldest profession. In between adventures and enjoyments, an Intelligence officer—a spy—must needs do a vast amount of grubby foundation-laying.

He sought the fancier office and keyed for information on Edwin Cairncross, Grand Duke of Hermes. That meant a historical and social review of the planet itself.

The sun, Maia (not to be confused with giant 20 Tauri), was in Sector Antares. Its attendants included a terrestroid globe which had been colonized early on, largely by northern Europeans. Basic conditions, including biology, were homelike enough that the settlement did well. The inevitable drawbacks included the concentration of most land in a single huge continent whose interior needed modification—for instance, entire systems of rivers and lakes to relieve its aridity—before it was fit for humans to live in. Meanwhile they prospered along the coasts. Originally their polity was a rather curious development out of private corporations, with a head of state elected from a particular family to serve for life or good behavior. Society got stratified in the course of time, and reaction against that was fuelled by the crisis that the Babur War brought. Reforms turned Hermes into an ordinary type of crowned republic.

The war had also resulted in making it an interstellar power. It assumed protectorship over the defeated Baburites; they were too alien for close relations, but what there were, political and commercial, appeared to have been pretty amicable through the centuries. Hermetians started colonies and enterprises in several nearby systems. Most significantly, they had stewardship of Mirkheim, the sole known source of supermetals.

They needed their wealth and strength, for the Troubles were upon Technic civilization. Wars, revolutions, plundering raids raged throughout its space. Hermes must often fight. This led to a military-oriented state and a concentration of authority in the executive. When at last Manuel had established the Terran Empire and its Pax was spreading afar, that state was able to join on highly favorable terms.

Afterward … well, naturally the files couldn’t say so; but as the Empire decayed, Hermes did too. Again and again, lordship went to the man with the armed force to take if. The economy declined, the sphere of influence shrank. Hans Molitor finally reasserted the supremacy of Terra. Generally he was welcomed by folk weary of chaos. But he had political debts to pay, and one payment involved putting lucrative Mirkheim directly under the Imperium. It was then a reasonable precaution to reduce sharply the autonomy of the Grand Duchy, disband its fighting services, require its businesses to mesh with some elsewhere—which worsened resentment. Riots erupted and Imperial agents were murdered, before the Marines restored order.

Today’s Duke, Edwin Cairncross, appeared properly submissive; but appearances were not very reliable across a couple of hundred light-years, and certainly he had several odd items in his record. Now fifty-five, he had been the youngest son by a second marriage of a predecessor who gave Hans much trouble before yielding. Thus he had no obvious prospect of becoming more than a member of the gentry. Reviving an old Hermetian tradition, he enlisted in the Imperial Navy for a five-year hitch and left it bearing the rank of lieutenant commander. That was only partly due to family; he had served well, earning promotions during the suppression of the Nyanzan revolt and in the Syrax confrontation.

Returning home, he embarked energetically on a number of projects. Among these, he enlarged what had been a petty industrial operation on the strange planet Ramnu and its moons. Meanwhile he held a succession of political posts and built up support for himself. Ten years ago, he became ready to compel the abdication of his older half-brother and his own election to the throne. Since then, he had put various measures into effect and undertaken various public works that were popular.

Hence on the surface, he seemed a desirable man in his position. The staff of the Imperial legate on Hermes were less sure of that. Their reports over the past decade showed increasing worry. Cairncross’ image, writings, recorded speeches were everywhere. Half the adolescents on the home globe joined an organization which was devoted to outdoorsmanship and sports but which was called the Cairncross Pioneers; its counselors preached a patriotism that was integral with adoration of him. Scholars were prodded into putting on symposia about his achievements and his prospects for restoring the greatness of his people. News media trumpeted his glories.

None of this was actually subversive. Many local lords exhibited egomania but were otherwise harmless. However, it was a possible danger signal. The impression was reinforced by the legate’s getting no more exact information than law required—on space traffic, demography, production and distribution of specified goods, etc.—and his agents being unable to gather more for themselves or even ascertain whether what they were given was accurate. “We respect the right of individual choice here” was the usual bland response to an inquiry. The Babur Protectorate had been virtually sealed off: ostensibly at the desire of the natives, who were not Imperial subjects and therefore were free to demand it; but how could an outsider tell? Anything might be in preparation, anywhere throughout a volume of space that included scores of suns. Recent messages from the legate urged that Terra mount a full investigation.

The recommendation has drowned, Flandry thought, in the data, pleas, alarms that come here from a hundred thousand worlds. It has never gotten anywhere near the attention of the Policy Board. No lower-echelon official has flagged it. Why should he? Hermes is far off, close to that march of the Empire. By no possibility could it muster the power to make itself independent again, let alone pose any serious threat to Terra. The clearly dangerous cases are too many, too many.

Is there a danger, anyway … when the Duke has arrived of his free will and wants to see me, of all unlikely candidates?

Flandry searched for personal items. They were surprisingly few, considering what a cult the chap had built around himself. Cairncross was long married, but childlessly; indications were that that was due to a flaw in him, not his wife. Yet he had never cloned, which seemed odd for an egotist unless you supposed that his vainglory was too much for him to make such an admission. He was a mighty womanizer, but usually picked his bedmates from the lower classes and took care to keep them humble. Men found him genial when he was in the right mood, though always somewhat overawing, and terrifying when he grew angry. He had no close friends, but was generally considered to be trustworthy and a just master. He was an ardent sportsman, hunter, crack shot; he piloted his own spacecraft and had explored lethally unterrestroid environments; he was an excellent amateur cabinetmaker; his tastes were fairly simple, except that he enjoyed and understood wine; distilled beverages he consumed a bit heavily, without showing any effects; he was not known to use more drugs than alcohol—

Flandry decided to receive him in this office.

“Welcome, your Grace.”

“Thank you.” A firm handshake ended. Cairncross was putting on no airs. “Please be seated. May I offer your Grace refreshments? I’m well stocked.”

“M-m-m … Scotch and soda, then. And let’s drop the titles while we’re the two of us. I aim to talk frankly.”

Chives shimmered in and took orders. Cairncross stared curiously after the Shalmuan—probably he’d never met any before—and swung attention back to his host. “Well, well,” he said. “So this is the legendary Admiral Flandry.”

“No, the objectively real Admiral Flandry, I hope. Some would say objectionably real.”

Cairncross formed a smile and a chuckle, both short-lived. “The objectors have ample cause,” he said. “Thank God for that.”

“Indeed?”

“They’ve been our enemies, haven’t they? I know why you got that medallion you’re wearing. The business wasn’t publicized—would’ve been awkward for diplomacy, right?—but a man in my kind of position has ways of learning things if he’s interested. You pulled the fangs of the Merseians at Chereion, and we no longer have to worry about them.”

Flandry quelled a wince, for that episode had cost him heavily. “Oh, but I’m afraid we do,” he said. “Their Intelligence apparatus suffered severe damage, true. However, nothing else did, and they’re hard at work rebuilding it. They’ll be giving us fun and games again.”

“Not if we stay strong.” Cairncross’ gaze probed and probed. “Which is basically what I’m here about.”

Flandry returned the look. Cairncross was tall and broad, with a tigerish suppleness to his movements. His face was wide on a wedge-shaped cranium, Roman-nosed, thin-lipped, fully de-bearded. The hair was red and starting to get scant, the eyes pale blue, the complexion fair and slightly freckled. His voice was deep and sonorous, crisply accented. He was wearing ordinary civilian garb, blouse and trousers in subdued hues, but a massive ring of gold and emerald sparkled on a furry finger.

Flandry lighted a cigarette. “Pray proceed,” he invited.

“Strength demands unity,” Cairncross replied. “Out my way, unity is threatened. I believe you can save it.”

Chives brought the whisky, a glass of white Burgundy, and canapes. When he had gone, the Duke resumed in a rush:

“You’ll have checked my dossier. You’re aware that I’m somewhat under suspicion. I’ve listened to your legate often enough; he makes no direct accusations, but he complains. Word that he sends here gets back to me through channels you can easily guess at. And I doubt if I’ll shock you by saying that, in self-defense, I’ve sicced agents of mine onto agents of the Imperium on Hermes, to learn what they’re doing and conjecturing. Am I secretly preparing for a revolt, a coup, or what? They wonder, yes, they wonder very hard.”

“Being suspected of dreadful things is an occupational hazard of high office, isn’t it?” Flandry murmured.

“But I’m innocent!” Cairncross protested. “I’m loyal! The fact of my presence on Terra—”

His tone eased: “I’ve grown more and more troubled about this. Finally I’ve decided to take steps. I’m taking them myself, rather than sending a representative, because, frankly, I’m not sure who I can trust any more.

“You know how impossible it is for a single man, no matter what power he supposedly has, to control everything, or know most of what’s going on. Underlings can evade, falsify, conceal, drag their feet; your most useful officials can be conspirators against you, biding their time—Well, you understand, Admiral.

“I’ve begun to think there actually is a conspiracy on Hermes. In that case, I am its sacrifical goat.”

Flandry trickled smoke ticklingly through his nostrils. “What do you mean, please?” he asked, though he thought he knew.

He was right. “Take an example,” Cairncross said. “The legate wants figures on our production of palladium and where it is consumed. My government isn’t technically required to provide that information, but it is required to cooperate with the representative of the Imperium, and his request for those figures is reasonable under the circumstances. After all, palladium is essential to protonic control systems, which are essential to any military machine. Now can I, personally, supply the data? Of course not. But when his agents try to collect them, and fail, I get blamed.”

“No offense,” Flandry said, “but you realize that, theoretically, the guilt could trace back to you. If you’d issued the right orders to the right individuals—”

Cairncross nodded. “Yes. Yes. That’s the pure hell of it.

“I don’t know if the plotters mean to discredit me so that somebody else can take my title, or if something worse is intended. I can’t prove there is a plot. Maybe not; maybe it’s an unfortunate set of coincidences. But I do know my good name is being gnawed away. I also know this kind of thing—disunity—can only harm the Empire. I’ve come for help.”

Flandry savored his wine. “I sympathize,” he said. “What can I do?”

“You’re known to the Emperor.”

Flandry sighed. “That impression dies hard, doesn’t it? I was moderately close to Hans. After he died, Dietrich consulted me now and then, but not frequently. And I’m afraid Gerhart doesn’t like me a whole lot.”

“Well, still, you have influence, authority, reputation.”

“These days, I have what amounts to a roving commission, and I can call on resources of the Corps. That’s all.”

“That’s plenty!” Cairncross exclaimed. “See here. What I want is an investigation that will exonerate me and turn up whatever traitors are nested in Hermes. It would look peculiar if I suddenly appeared before the Policy Board and demanded this; it would damage me politically at home, as you can well imagine. But a discreet investigation, conducted by a person of unimpeachable loyalty and ability—Do you see?”

Loyalty? passed through Flandry. To what? Scarcely to faithless Gerhart; scarcely even to this walking corpse of an Empire. Well, to the Pax, I suppose; to some generations of relative security that people can use to live in, before the Long Night falls; to my corps and my job, which have given me quite a bit of satisfaction; to a certain tomb on Dennitza, and to various memories.

“I can’t issue several planets a clean bill of health just by myself,” he said.

“Oh, no,” Cairncross answered. “Gather what staff you need. Take as much time as you like. You’ll get every kind of cooperation I’m able to give. If you don’t get it from elsewhere, well, isn’t that what your mission will be about?”

“Hm.” I have been idle for awhile. It is beginning to pall. Besides, I’ve never been on Hermes; and from what little I know about them, planets like Babur and Ramnu may prove fascinating. “It definitely interests; and, as you say, it could affect a few billion beings more than you. What have you in mind, exactly?”

“I want you and your immediate aides to come back with me at once,” Cairncross said. “I’ve brought my yacht; she’s fast. I realize that’ll be too few personnel, but you can reconnoiter and decide what else to send for.”

“Isn’t this rather sudden?”

“Damn it,” Cairncross exploded, “I’ve been strangling in the net for years! We may not have much time left.” Calmer: “Your presence would help by itself. We’d not make a spectacle of it, of course, but the right parties—starting with his Majesty’s legate—would know you’d come, and feel reassured.”

“A moment, please, milord.” Flandry stretched out an arm and keyed his infotrieve. What he wanted flashed onto the screen.

“The idea tempts,” he said, “assuming that one can be tempted to do a good deed. You’ll understand that I’d have arrangements to make first. Also, I’ve grown a smidgin old for traveling on a doubtless comfortless speedster; and I might want assistants from the start who themselves cannot leave on short notice.” He waved a hand. “This is assuming I undertake the assignment. I’ll have to think further about that. But as for a preliminary look-see, well, I note that the Queen of Apollo arrives next week. She starts back to Hermes three days later, and first class accommodations are not filled. We can talk en route. Your crew can take your boat home.”

Cairncross flushed. He smote the arm of his seat. “Admiral, this is an Imperial matter. It cannot wait.”

“It has waited, by your account,” Flandry drawled. Instinct, whetted throughout a long career, made him add: “Besides, I need answers to a hundred questions before I can know whether I ought to do this.”

“You will do it!” Cairncross declared. Catching his breath: “If need be—the Emperor is having a reception for me, the normal thing. I’ll speak to him about this if you force me to. I would prefer, for your sake, that you don’t get a direct order from the throne; but I can arrange it if I must.”

“Sir,” Flandry purred, while his inwardness uncoiled itself for action, “my apologies. I meant no disrespect. You’ve simply taken me by surprise. Please think. I’ve commitments of my own. In fact, considering them, I realize they require my absence for about two weeks. After that, I can probably make for Hermes in my personal craft. When I’ve conducted enough interviews and studies there, I should know who else to bring.”

He lifted his glass. “Shall we discuss details, milord?”

Hours later, when Cairncross had left, Flandry thought: Oh, yes, something weird is afoot in Sector Antares.

Perhaps the most suggestive thing was his reaction to my mention of the Queen of Apollo. He tried to hide it, but … Now who or what might be aboard her?

IV

Banner had not seen Terra since she graduated at the age of twenty-one, to marry Sumarokov and depart for Ramnu. Moreover, the Academy had been an intense, largely self-contained little world, from which cadets seldom found chances to venture during their four years. She had not hankered to, either. Childhood on Dayan, among the red-gold Tammuz Mountains, followed by girlhood as a Navy brat in the strange outposts where her father got stationed, had not prepared her for any gigapolis. Nor had her infrequent later visits to provincial communities. Starfall, the biggest, now seemed like a village, nearly as intimate and unterrifying as Bethyaakov her birthplace.

She had made acquaintances in the ship. A man among them had told her a number of helpful facts, such as the names of hotels she could afford in the capital. He offered to escort her around as well, but his kindnesses were too obviously in aid of getting her into bed, and she resented that. Only one of her few affairs had been a matter of real love, but none had been casual.

Thus she found herself more alone, more daunted among a million people and a thousand towers, than ever in a wildwood or the barrenness of a moon. Maybe those numbers, million, thousand, were wrong. It felt as if she could see that many from the groundside terminal, but she was dazed. She did know that they went on beyond sight, multiplied over and over around the curve of the planet. Archopolis was merely a nexus; no matter if the globe had blue oceans and green open spaces—some huge, being property of nobility—it was a single city.

She collected her modest baggage, hailed a cab, blurted her destination to the autopilot, and fled. In nightmare beauty, the city gleamed, surged, droned around her.

At first the Fatima Caravanserai seemed a refuge. It occupied the upper third of an unpretentious old building, and had itself gone dowdy; yet it was quiet, reasonably clean, adequately equipped, and the registry desk held a live clerk, not a machine, who gave her cordial greeting and warned against the fish in the restaurant; the meat was good, he said.

But when she entered her room and the door slid shut, suddenly it was as though the walls drew close.

Nonsense! she told herself. I’m tired and tense. I need to relax, and this evening have a proper dinner, with wine and the works.

And who for company?

That question chilled. Solitude had never before oppressed her. If anything, she tended to be too independent of her fellow humans. But it was horrible to find herself an absolute stranger in an entire world.

Nonsense! she repeated. I do know Admiral Flandry … slightly … Will he remember me? No doubt several of my old instructors are still around … Are they? The Xenological Society maintains a clubhouse, and my name may strike a chord in somebody if I drop in … Can it?

A cigarette between her lips, she began a whirl of unpacking. Thereafter a hot shower and a soft robe gave comfort. She blanked the viewerwall and keyed for a succession of natural scenes and historic monuments which the infotrieve told her was available, plus an excellent rendition of the pipa music she particularly enjoyed. The conveyor delivered a stiff cognac as ordered. Local time was 1830; in a couple of hours she might feel like eating. Now she settled down in a lounger to ease off.

No. She remained too restless. Rising, prowling, she reached the phone. There she halted. For a moment her fingers wrestled each other. It would likely be pointless to try calling Flandry before tomorrow. And then she could perhaps spend days getting her message through. A prominent man on Terra must have to live behind a shield-burg of subordinates.

Well, what harm in finding out the number?

That kept the system busy for minutes, since she did not know how to program its search through the bureaucratic structure. No private listing turned up, nor had she expected any. Two strings of digits finally flashed onto the screen. The first was coded for “Office,” the second for “Special.”

Was the latter an answering service? In that case, she could record her appeal immediately.

To her surprise, a live face appeared, above a uniform that sported twin silver comets on the shoulders. To her amazement, though the Anglic she heard was unmistakably Terran, the person was an alert-looking young woman. Banner had had the idea that Terran women these days were mostly ornaments, drudges, or whores. “Lieutenant Okuma,” she heard. “May I help you?”

“I—well, I—” Banner collected herself. “Yes, please. I’m anxious to get in touch with Admiral Flandry. It’s important. If you’ll tell him my name, Miriam Abrams, and remind him I’m the daughter of Max Abrams, I’m sure he—”

“Hold on!” Okuma rapped. “Have you newly arrived?”

“Yes, a few hours ago.”

“On the Queen of Apollo?”

“Why, yes, but—”

“Have you contacted anybody else?”

“Only customs and immigration officers, and the hotel staff, and—” Banner bridled. “What does this mean?”

“Excuse me,” Okuma said. “I believe it means a great deal. I’ve been manning this line all day. Don’t ask me why; I’ve not been told.” She leaned forward. Her manner intensified. “Would you tell me where you are and what you want?”

“Fatima Caravanserai, Room 776,” Banner blurted, “and I’m hoping he’ll use his influence on behalf of a sophont species that desperately needs help. The Grand Duke of Hermes has refused it, so—” Her words faltered, her heart stammered.

“Grand Duke, eh? … Enough,” Okuma said. “Please pay attention. Admiral Flandry has been called away on business. Where, has not been given out, and he isn’t expected back until next week.”

“Oh, I can wait.”

“Listen! I have a message for whoever might debark from the Queen and try calling him. That seems to be you, Donna Abrams. Stay where you are. Keep the door double-secured. Do not leave on any account. Do not admit anyone whatsoever, no matter what that person may claim, unless he gives you a password. When you hear it, be prepared to leave immediately. Do what you are told, and save your questions till later, when you’re safe. Do you understand?”

“What? No, I don’t. What’s wrong?”

“I have not been informed.” The lieutenant’s mouth twisted into a smile. “But Sir Dominic is usually right about such things.”

Banner had met danger more than once. She had always found it exhilarating. Her back straightened, her pulse slowed. Having repeated the instructions, she asked, “What’s the password?”

“’Basingstoke.’” Okuma smiled again, wryly. “I don’t know what it signifies. He has an odd sense of humor. Stand by. I’ve a call to make. Good luck.” The screen darkened.

Banner started repacking.

The phone chimed.

The face she saw when she accepted was round and rubicund under yellow curls. “Dr. Abrams?” the man said. “Welcome to Terra. My name is Leighton, Tom Leighton, and I’m in the lobby. May I come up, or would you like to come down and join me?”

Again she sensed her aloneness. “Why?” she whispered.

“Well, I’m a colleague of yours. I’ve admired your work tremendously; those are classic presentations. By sheer chance, I was meeting a friend off the Queen of Apollo today, and he mentioned you’d been aboard. Believe me, it took detective work to track you down! Apparently you threw yourself into a cab and disappeared. I’ve had a data scan checking every hotel and airline and—Well, anyway, Dr. Abrams, I was hoping we could go out to dinner. My treat. I’d be honored.”

She stared into the bland blue eyes. “Tell me,” she said, “what do you think of the cater-cousin relationship among the Greech on Ramnu?”

“Huh?”

“Do you agree with me it’s religious in origin, or do you think Brunamonti is right and it’s a relic of the former military organization?”

“Oh, that! I agree with you absolutely.”

“How interesting,” Banner said, “in view of the fact that no such people as the Greech exist, that Ramnuans don’t have religions of human type and most definitely have never had armies, and nobody named Brunamonti has ever done xenology on their planet. Have you any further word for me, Citizen Leighton?”

“Ah, wait, wait a minute—”

She cut him off.

Presently her door was pealing. She punched the callbox and his voice came through: “Dr. Abrams, please, this is a terrible misunderstanding. Let me in and I’ll explain.”

“Go away.” Despite the steadiness in her voice, her flesh crawled. She was concerned.

“Dr. Abrams, I must insist. The matter involves a very high-ranking person. If you don’t open the door, we’ll have to take measures.”

“Or I will. Like calling the police.”

“I tell you, it’s a top-grade noble who wants to see you. He can have the police break you out of there. He’d rather not, because what he wants is for your benefit too, but—Uh, who are you?” Leighton asked somebody else. “What do you want?”

“Basingstoke,” rippled a baritone voice. A moment later, Banner heard a thud. “You can open up now,” the newcomer continued.

She did. Leighton lay in a huddle on the hall floor. Above him stood a figure in a hooded cloak. He drew the cowl back and she knew Flandry.

He gestured at the fallen shape. “A stun gun shot,” he said. “I’ll drag him in here to sleep it off. He’s not worth killing, just a petty predator hired through an agency that provides reputable people with disreputable services. He’s probably got a companion or two down below, on the qui vive. We’ll spirit you upward. Chives—do you remember Chives?—has an aircar on the roof for us.” He bowed and quickly, deftly kissed her hand. “I’m sorry about this informal reintroduction, my dear. I’ll try to make amends at dinner. We have a reservation a couple of hours hence at Deirdre’s. You wouldn’t believe what they do with seafood there.”

V

His Imperial Majesty, High Emperor Gerhart Siegmund Molitor, graciously agreed to withdraw from the reception for a private talk with its guest of honor. They passed in stateliness through the swirl of molten rainbows which several hundred costumes made of the grand ballroom. Folk bowed, curtsied, or saluted, depending on status, and hoped for a word from the august mouth. A few got one, and promptly became centers of eager attention. There were exceptions to this, of course, mostly older men of reserved demeanor, admirals, ministers of state, members of the Policy Board, the power brokers. Their stares followed the Duke of Hermes. He would be invited later to meet with various of them.

A gravshaft took Gerhart and Cairncross to a suite in the top of the loftiest tower that the Coral Palace boasted. The guards outside were not gorgeously uniformed like those on ground level; they were hard of face and hands, and their weapons had seen use. Gerhart motioned them not to follow, and let the door close behind himself and his companion.

A clear dome overlooked lower roofs, lesser spires, gardens, trianons, pools, bowers, finally beach, sand, surf, nearby residential rafts, and the Pacific Ocean. Sheening and billowing under a full Luna, those waters gave a sense of ancient forces still within this planet that man had so oedipally made his own, still biding their time. That feeling was strengthened by the sparsely furnished chamber. On the floor lay a rug made from the skin of a Germanian dolchzahn, on a desk stood a model of a corvette, things which had belonged to Hans. His picture hung on the wall. It had been taken seven years ago, shortly before his death, and Cairncross saw how wasted the big ugly countenance had become by then; but in caverns of bone, the gaze burned.

“Sit down,” Gerhart said. “Smoke if you wish.”

“I don’t, but your Majesty is most kind.”

Gerhart sighed. “Spare me the unction till we have to go back. When the lord of a fairly significant province arrives unannounced on Terra, I naturally look at whatever file we have on him. You don’t strike me as the sort who would come here for a vacation.”

“No, that was my cover story, … sir.” The Emperor having taken a chair, the Duke did likewise.

“Ye-es,” Gerhart murmured, “it is interesting that you put your head in the lion’s mouth. Why?”

Cairncross regarded him closely. He didn’t seem leonine, being of medium height, with blunt, jowly features and graying sandy hair. The iridescent, carefully draped robe he wore could not quite hide the fact that, in middle age, he was getting pudgy. But he had his father’s eyes, small, dark, searching, the eyes of a wild boar.

He smiled as he opened a box and took out a cigar for himself. “Interesting enough,” he went on, “that I’ve agreed to receive you like this. Ordinarily, you know, any special audiences you got would be with persons such as Intelligence officers.”

“Frankly, sir,” Cairncross answered, emboldened, “I started out that way, but got no satisfaction. Or so it appears. Maybe I’m doing the man an injustice. You can probably tell me—though Admiral Flandry is a devious devil, isn’t he?”

“Flandry, eh? Hm-m.” Gerhart kindled the cigar. Smoke curled blue and pungent. “Proceed.”

“Sir,” Cairncross began, “having seen my file, you know about the accusations and innuendos against me. I’m here partly to declare them false, to offer my body as a token of my loyalty. But you’ll agree that more is needed, solid proof … not only to exonerate me, but to expose any actual plot.”

“This is certainly an age of plots,” Gerhart observed, through the same cold smile as before.

And murders, revolutions, betrayals, upheavals, Cairncross replied silently. Brother against brother—When that spacecraft crashed, Gerhart, and killed Dietrich, was it really an accident? Incredible that safety routines could have slipped so far awry, for a ship which would carry the Emperor. Never mind what the board of inquiry reported afterward; the new Emperor kept tight control of its proceedings.

You are widely believed to be a fratricide, Gerhart. (And a parricide? No; old Hans was too shrewd.) If you are nevertheless tolerated on the throne, it is because you are admittedly more able than dullard Dietrich was. The Empire needs a strong, skilled hand upon it, lest it splinter again in civil war and the Merseians or the barbarians return.

Yet that is your only claim to rulership, Gerhart. It was Hans’ only claim, too. He, however, was coping as best he could, after the Wang dynasty fell apart. There was no truly legitimate heir. When most of the Navy rallied to him, he could offer domestic order and external security, at the cost of establishing a military dictatorship.

But … no blood of the Founder ever ran in his veins. His coronation was a solemn farce, played out under the watch of his Storm Corps, whose oath was not to the Imperium but to him alone. He broke aristocrats and made new ones at his pleasure. He kept no ancient pacts between Terra and her daughter worlds, unless they happened to suit his purposes. Law became nothing more than his solitary will.

He is of honored memory here, because of the peace he restored. That is not the case everywhere else …

“You are suddenly very quiet,” Gerhart said.

Cairncross started. “I beg your pardon, sir. I was thinking how to put my case with the least strain on your time and patience.”