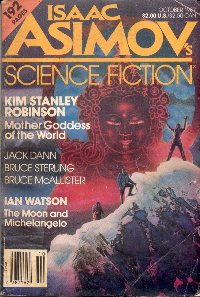

Mother Goddess of the World

by Kim Stanley Robinson

I

My life started to get weird again the night I ran into Freds Fredericks, near Chimoa, in the gorge of the Dudh Kosi. I was guiding a trek at the time, and was very happy to see Freds. He was traveling with another climber, a Tibetan by the name of Kunga Norbu, who appeared to speak little English except for “Hello” and “Good morning,” both of which he said to me as Freds introduced us, even though it was just after sunset. My trekking group was settled into their tents for the night, so Freds and Kunga and I headed for the cluster of teahouses tucked into the forest by the trail. We looked in them; two had been cleaned up for trekkers, and the third was a teahouse in the old style, frequented only by porters. We ducked into that one.

It was a single low room; we had to stoop not only under the beams that held up the slate roof, but also under the smoke layer. Old-style country buildings in Nepal do not have chimneys, and the smoke from their wood stoves just goes up to the roof and collects there in a very thick layer, which lowers until it begins to seep out under the eaves. Why the Nepalis don’t use chimneys, which I would have thought a fairly basic invention, is a question no one can answer; it is yet another Great Mystery of Nepal.

Five wooden tables were occupied by Rawang and Sherpa porters, sprawled on the benches. At one end of the room the stove was crackling away. Flames from the stove and a hissing Coleman lantern provided the light. We said Namaste to all the staring Nepalis, and ducked under the smoke to sit at the table nearest the stove, which was empty.

We let Kunga Norbu take care of the ordering, as he had more Nepalese than Freds or me. When he was done the Rawang stove keepers giggled and went to the stove, and came back with three huge cups of Tibetan tea.

I complained to Freds about this in no uncertain terms. “Damn it, I thought he was ordering chang!”

Tibetan tea, you see, is not your ordinary Lipton’s. To make it they start with a black liquid that is not made from tea leaves at all but from some kind of root, and it is so bitter you could use it for suturing. They pour a lot of salt into this brew, and stir it up, and then they dose it liberally with rancid yak butter, which melts and floats to the top.

It tastes worse than it sounds. I have developed a strategy for dealing with the stuff whenever I am offered a cup; I look out the nearest window, and water the plants with it. As long as I don’t do it too fast and get poured a second cup, I’m fine. But here I couldn’t do that, because twenty-odd pairs of laughing eyes were staring at us.

Kunga Norbu was hunched over the table, slurping from his cup and going “ooh,” and “ahh,” and saying complimentary things to the stove keepers. They nodded and looked closely at Freds and me, big grins on their faces.

Freds grabbed his cup and took a big gulp of the tea. He smacked his lips like a wine taster. “Right on,” he said, and drained the cup down. He held it up to our host. “More?” he said, pointing into the cup.

The porters howled. Our host refilled Freds’s cup and he slurped it down again, smacking his lips after every swallow. I slipped some iodine solution into mine from a dropper I keep on me, and stirred it around and held my nose to get down a sip, and they thought that was funny too.

So we were in tight with the teahouse crowd, and when I asked for chang they brought over a whole bucket of it. We poured it into the little chipped teahouse glasses and went to work on it.

“So what are you and Kunga Norbu up to?” I asked him.

“Well,” he said, and a funny expression crossed his face. “That’s kind of a long story, actually.”

“So tell it to me.”

He looked uncertain. “It’s too long to tell tonight.”

“What’s this? A story too long for Freds Fredericks to tell? Impossible, man, why I once heard you summarize the Bible to Laure, and it only took you a minute.”

Freds shook his head. “It’s longer than that.”

“I see.” I let it go, and the three of us kept on drinking the chang, which is a white beer made from rice or barley. We drank a lot of it, which is a dangerous proposition on several counts, but we didn’t care. As we drank we kept slumping lower over the table to try to get under the smoke layer, and besides we just naturally felt like slumping at that point. Eventually we were laid out like mud in a puddle.

Freds kept conferring with Kunga Norbu in Tibetan, and I got curious. “Freds, you hardly speak a word of Nepali, how is it you know so much Tibetan?”

“I spent a couple years in Tibet. I was studying in the Buddhist lamaseries there.”

“You studied in Buddhist lamaseries in Tibet?”

“Yeah sure! Can’t you tell?”

“Well…” I waved a hand. “I guess that might explain it.”

“That was where I met Kunga Norbu, in fact. He was my teacher.”

“I thought he was a climbing buddy.”

“Oh he is! He’s a climbing lama. Actually there’s quite a number of them. See when the Chinese invaded Tibet they closed down all the lamaseries, destroyed most of them in fact. The monks had to go to work, and the lamas either slipped over to Nepal, or moved up into mountain caves. Then later the Chinese wanted to start climbing mountains as propaganda efforts, to show the rightness of the thoughts of Chairman Mao. The altitude in the Himalayas was a little bit much for them, though, so they mostly used Tibetans, and called them Chinese. And the Tibetans with the most actual mountain experience turned out to be Buddhist monks, who had spent a lot of time in really high, isolated retreats. Eight of the nine so-called Chinese to reach the top of Everest in 1975 were actually Tibetans.”

“Was Kunga Norbu one of them?”

“No. Although he wishes he was, let me tell you. But he did go pretty high on the North Ridge in the Chinese expedition of 1980. He’s a really strong climber. And a great guru too, a really holy guy.”

Kunga Norbu looked across the table at me, aware that we were talking about him. He was short and skinny, very tough looking, with long black hair. Like a lot of Tibetans, he looked almost exactly like a Navaho or Apache Indian. When he looked at me I got a funny feeling; it was as if he were staring right through me to infinity. Or somewhere equally distant. No doubt lamas cultivate that look.

“So what are you two doing up here?” I asked, a bit uncomfortable.

“We’re going to join my Brit buddies, and climb Lingtren. Should be great. And then Kunga and I might try a little something on our own.”

We found we had finished off the bucket of chang, and we ordered another. More of that and we became even lower than mud in a puddle.

Suddenly Kunga Norbu spoke to Freds, gesturing at me. “Really?” Freds said, and they talked some more. Finally Freds turned to me. “Well, this is a pretty big honor, George. Kunga wants me to tell you who he really is.”

“Very nice of him,” I said. I found that with my chin on the table I had to move my whole head to speak.

Freds lowered his voice, which seemed to me unnecessary as we were the only two people in the room who spoke English. “Do you know what a tulku is, George?”

“I think so,” I said. “Some of the Buddhist lamas up here are supposed to be reincarnated from earlier lamas, and they’re called tulkus, right? The abbot at Tengboche is supposed to be one.”

Freds nodded. “That’s right.” He patted Kunga Norbu on the shoulder. “Well, Kunga here is also a tulku.”

“I see.” I considered the etiquette of such a situation, but couldn’t really figure it, so finally I just scraped my chin off the table and stuck my hand across the table. Kunga Norbu took it and shook, with a modest smile.

“I’m serious,” Freds said.

“Hey!” I said. “Did I say you weren’t serious?”

“No. But you don’t believe it, do you.”

“I believe that you believe it, Freds.”

“He really is a tulku! I mean I’ve seen proof of it, I really have. His ku kongma, which means his first incarnation, was as Tsong Khapa, a very important Tibetan lama born in 1555. The monastery at Kum-Bum is located on the site of his birth.”

I nodded, at a loss for words. Finally I filled up our little cups, and we toasted Kunga Norbu’s age. He could definitely put down the chang like he had had lifetimes of practice. “So,” I said, calculating. “He’s about four hundred and thirty-one.”

“That’s right. And he’s had a hard time of it, I’ll tell you. The Chinese tore down Kum-Bum as soon as they took over, and unless the monastery there is functioning again, Tsong Khapa can never escape being a disciple. See, even though he is a major tulku—”

“A major tulku,” I repeated, liking the sound of it.

“Yeah, even though he’s a major tulku, he’s still always been the disciple of an even bigger one, named Dorjee. Dorjee Lama is about as important as they come—only the Dalai Lama tops him—and Dorjee is one hard, hard guru.”

I noticed that the mention of Dorjee’s name made Kunga Norbu scowl, and refill his glass.

“Dorjee is so tough that the only disciple who has ever stuck with him has been Kunga here. Dorjee—when you want to become his student and you go ask him, he beats you with a stick. He’ll do that for a couple of years to make sure you really want him as a teacher. And then he really puts you through the wringer. Apparently he uses the methods of the Ts’an sect in China, which are tough. To teach you the Short Path he pounds you in the head with his shoe.”

“Now that you mention it, he does look a little like a guy who has been pounded in the head with a shoe.”

“How can he help it? He’s been a disciple of Dorjee’s for four hundred years, and it’s always the same thing. So he asked Dorjee when he would be a guru in his own right, and Dorjee said it couldn’t happen until the monastery built on Kunga’s birth site was rebuilt. And he said that that would never happen until Kunga managed to accomplish—well, a certain task. I can’t tell you exactly what the task is yet, but believe me it’s tough. And Kunga used to be my guru, see, so he’s come to ask me for some help. So that’s what I’m here to do.”

“I thought you said you were going to climb Lingtren with your British friends?”

“That too.”

I wasn’t sure if it was the chang or the smoke, but I was getting a little confused. “Well, whatever. It sounds like a real adventure.”

“You’re not kidding.”

Freds spoke in Tibetan to Kunga Norbu, explaining what he had said to me, I assumed. Finally Kunga replied, at length.

Freds said to me, “Kunga says you can help him too.”

“I think I’ll pass,” I said. “I’ve got my trekking group and all, you know.”

“Oh I know, I know. Besides, it’s going to be tough. But Kunga likes you—he says you have the spirit of Naropa.”

Kunga nodded vigorously when he heard the name Naropa, staring through me with that spacy look of his.

“I’m glad to hear it,” I said. “But I still think I’ll pass.”

“We’ll see what happens,” Freds said, looking thoughtful.

II

Many glasses of chang later we staggered out into the night. Freds and Kunga Norbu slipped on their down jackets, and with a “Good night” and a “Good morning” they wandered off to their tent. I made my way back to my group. It felt really late, and was maybe eight-thirty.

As I stood looking at our tent village, I saw a light bouncing down the trail from Lukla. The man carrying the flashlight approached—it was Laure, the sirdar for my group. He was just getting back from escorting clients back to Lukla. “Laure!” I called softly.

“Hello George,” he said. “Why late now?”

“I’ve been drinking.”

“Ah.” With his flashlight pointed at the ground I could easily make out his big smile. “Good idea.”

“Yeah, you should go have some chang yourself. You’ve had a long day.”

“Not long.”

“Sure.” He had been escorting disgruntled clients back to Lukla all day, so he must have hiked five times as far as the rest of us. And here he was coming in by flashlight. Still, I suppose for Laure Tenzing Sherpa that did not represent a particularly tough day. As guide and yakboy he had been walking in these mountains all his life, and his calves were as big around as my thighs. Once, for a lark, he and three friends had set a record by hiking from Everest Base Camp to Kathmandu in four days; that’s about two hundred miles, across the grain of some seriously uneven countryside. Compared to that today’s work had been like a walk to the mailbox, I guess.

The worst part had no doubt been the clients. I asked him about that and he frowned. “People go co-op hotel, not happy. Very, very not happy. They fly back Kathmandu.”

“Good riddance,” I said. “Why don’t you go get some chang.”

He smiled and disappeared into the dark.

I looked over the tents holding my sleeping clients and sighed.

So far it had been a typical videotrek. We had flown in to Lukla from Kathmandu. My clients, enticed to Nepal by glossy ads that promised them video Ansel Adamshood, had gone wild in the plane, rushing about banging zoom lenses together and so on. They were irrepressible until they saw the Lukla strip, which from the air looks like a toy model of a ski jump. Pretty quickly they were strapped in and looking like they were reconsidering their wills—all except for one tubby little guy named Arnold, who continued to roll up and down the aisle like a bowling ball, finally inserting himself into the cockpit so he could shoot over the pilots’ shoulders. “We are landing at Lukla,” he announced to his camera’s mike in a deep fakey voice, like the narrator of a bad travelogue. “Looks impossible, but our pilots are calm.”

Despite him we landed safely. Unfortunately one of our group then tried to film his own descent from the plane, and fell heavily down the steps. As I ascertained the damage—a sprained ankle—there was Arnold again, leaning over to immortalize the victim’s every writhe and howl.

A second plane brought in the rest of our group, led by Laure and my assistant Heather. We started down the trail. For a couple of hours everything went well—the trail serves as the Interstate Five of the region, and is as easy as they come. And the view is awesome—the Dudh Kosi valley is like a forested Grand Canyon, only bigger. Our group was impressed, and several of them filmed a real-time record of the day.

Then the trail descended to the banks of the Dudh Kosi river, and we got a surprise. Apparently in the last monsoon a glacial lake upstream had burst its ice dam, and rushed down in a devastating flood, tearing out the bridges, trail, trees, everything. Thus our fine interstate ended abruptly in a cliff overhanging the torn-to-shreds riverbed, and what came next was the seat-of-the-pants invention of the local porters, for whom the trail was a daily necessity. They had been clever indeed, but there really was no good alternative to the old route; so the new trail wound over strewn white boulders in the riverbed, traversed unstable new sand cliffs, and veered wildly up and down muddy slides that had been hacked out of dense forested walls. It was radical stuff, and even experienced trekkers were having trouble.

Our group was appalled. The ads had not mentioned this.

The porters ran ahead barefoot to reach the next tea break, and the clients began to bog down. People slipped and fell. People sat down and cried. Altitude sickness was mentioned more than once, though as a matter of fact we were not much higher than Denver. Heather and I ran around encouraging the weary. I found myself carrying three videocameras. Laure was carrying nine.

It was looking like the retreat from Moscow when we came to the first of the new bridges. These are pretty neat pieces of backwoods engineering; there aren’t any logs in the area long enough to span the river, so they take four logs and stick them out over the river, and weigh them down with a huge pile of round stones. Then four more logs are pushed out from the other side, until their ends rest on the ends of the first four. Instant bridge. They work, but they are not confidence builders.

Our group stared at the first one apprehensively. Arnold appeared behind us and chomped an unlit cigar as he filmed the scene. “The Death Bridge,” he announced into his camera’s mike.

“Arnold, please,” I said. “Mellow out.”

He walked down to the glacial gray rush of the river. “Hey, George, do you think I could take a step in to get a better shot of the crossing?”

“NO!” I stood up fast. “One step in and you’d drown, I mean look at it!”

“Well, okay.”

Now the rest of the group were staring at me in horror, as if it weren’t clear at first glance that to fall into the Dudh Kosi would be a very fatal error indeed. A good number of them ended up crawling across the bridge on hands and knees. Arnold got them all for posterity, and filmed his own crossing by walking in circles that made me cringe. Silently I cursed him; I was pretty sure he had known perfectly well how dangerous the river was, and only wanted to make sure everyone else did too. And very soon after that—at the next bridge, in fact—people began to demand to be taken back to Lukla. To Kathmandu. To San Francisco.

I sighed, remembering it. And remembering that this was only the beginning. Just your typical Want To Take You Higher Ltd. videotrek. Plus Arnold.

III

I got another bit of Arnold in action early the next morning, when I was in the rough outhouse behind the trekkers’ teahouses, very hung over, crouched over the unhealthy damp hole in the floor. I had just completed my business in there when I looked up to see the big glass eye of a zoom lens, staring over the top of the wooden door at me.

“No, Arnold!” I cried, struggling to put my hand over the lens while I pulled up my pants.

“Hey, just getting some local color,” Arnold said, backing away. “You know, people like to see what it’s really like, the details and all, and these outhouses are really something else. Exotic.”

I growled at him. “You should have trekked in from Jiri, then. The lowland villages don’t have outhouses at all.”

His eyes got round, and he shifted an unlit cigar to the other side of his mouth. “What do you do, then?”

“Well, you just go outside and have a look around. Pick a spot. They usually have a shitting field down by the river. Real exotic.”

He laughed. “You mean, turds everywhere?”

“Well, something like that.”

“That sounds great! Maybe I’d better walk back out instead of flying.”

I stared at him, wrinkling my nose. “Serious filmmaker, eh Arnold?”

“Oh, yeah. Haven’t you heard of me? Arnold McConnell? I make adventure films for PBS. And sometimes for the ski resort circuit, video rentals, that kind of thing. Skiing, hang gliding, kayaking, parachuting, climbing, skateboarding—I’ve done them all. Didn’t you ever see The Man Who Swam Down the Zambesi? No? Ah, that’s a bit of a classic, now. One of my best.”

So he had known how dangerous the Dudh Kosi was. I stared at him reproachfully. It was hard to believe he made adventure films; he looked more like the kind of Hollywood producer you’d tell couch jokes about. “So you’re making a real film of this trip?” I asked.

“Yeah, sure. Always working, never stop working. Workaholic.”

“Don’t you need a bigger crew?”

“Well sure, usually, but this is a different kind of thing, one of my ‘personal diary’ films I call them. I’ve sold a couple to PBS. Do all the work myself. It’s kind of like my version of solo climbing.”

“Fine. But cut the part about me taking a crap, okay?”

“Sure, sure, don’t worry about it. Just got to get everything I can, you know, so I’ve got good tape to choose from later on. All grist for the mill. That’s why I got this lens. All the latest in equipment for me. I got stuff you wouldn’t believe.”

“I believe.”

He chomped his cigar. “Just call me Mr. Adventure.”

“I will.”

IV

I didn’t see Freds and Kunga Norbu in Namche Bazaar, and I figured they had left already with Freds’s British friends; I probably wouldn’t see them again until we got up near their base camp, because I planned to keep my group in Namche a couple days to acclimatize, and enjoy the town. Namche functions as the Sherpas’ capital, and a more dramatically placed town you could hardly imagine; it is perched on a promontory above the confluence of the Dudh Kosi and the Bhote Kosi, and the rivers lie about a mile below in steep green gorges, while white peaks tower a mile above all around it. The town itself is a horseshoe-shaped ring of stone buildings and stone streets, packed with Sherpas, trekkers, climbers, and traders dropping in for the weekly bazaar.

It’s a fun town, and kept me busy; I forgot about Freds and the Brits, and so was quite surprised to run into them in Pheriche, one of the Sherpas’ high mountain villages.

Most of these high villages are occupied only in the summer, to grow potatoes and pasture yaks. Pheriche, however, lies on the trekking route to Everest, so it’s occupied almost year-round, and a couple lodges have been built, along with the Himalayan Rescue Association’s only aid station. It still looks like a summer pasturage: low rock walls separate potato fields, and a few slate-roofed stone huts, plus the lodges and the tin-roofed aid station. All of it is clustered at the end of a flat-bottomed glacial valley, against the side of a lateral moraine five hundred feet high. A stream meanders by, and the ground is carpeted with grasses and the bright autumn red of berberi bushes. On all sides tower the fantastic white spikes of some of the world’s most dramatic peaks—Ama Dablam, Taboche, Tramserku, Kang Taiga—and all in all, it’s quite a place. My clients were making themselves dizzy trying to film it.

We set up our tent village in an unused potato field, and after dinner Laure and I slipped off to the Himalaya Hotel to have some chang. I entered the lodge’s little kitchen and heard Freds cry, “Hey George!” He was sitting with Kunga Norbu and four Westerners; we joined them, crowding in around a little table. “These are the friends we’re climbing with.”

He introduced them, and we all shook hands. Trevor was a tall slender guy, with round glasses and a somewhat crazed grin. “Mad Tom,” as Freds called him, was short and curly-headed, and didn’t look mad at all, although something in his mild manner made me believe that he could be. John was short and compact, with a salt-and-pepper beard, and a crusher handshake. And Marion was a tall and rather attractive woman—though I suspected she might have blushed or punched you if you said so—she was attractive in a tough, wild way, with a stark strong face, and thick brown hair pulled back and braided. They were British, with the accents to prove it: Marion and Trevor quite posh and public school, and John and Mad Tom very thick and North Country.

We started drinking chang, and they told me about their climb. Lingtren, a sharp peak between Pumori and Everest’s West Shoulder, is serious work from any approach, and they were clearly excited about it, in their own way: “Bit of a slog, to tell the truth,” Trevor said cheerfully.

When British climbers talk about climbing, you have to learn to translate it into English. “Bit of a slog” means don’t go there.

“I think we ought to get lost and climb Pumori instead,” said Marion. “Lingtren is a perfect hill.”

“Marion, really.”

“Can’t beat Lingtren’s price, anyway,” said John.

He was referring to the fee that the Nepali government makes climbers pay for the right to climb its peaks. These fees are determined by the height of the peak to be climbed—the really big peaks are super expensive. They charge you over five thousand dollars to climb Everest, for instance, and still competition to get on its long waiting list is fierce. But some of the toughest climbs in Nepal aren’t very high, relative to the biggies, and they come pretty cheap. Apparently Lingtren was one of these.

We watched the Sherpani who runs the lodge cook dinner for fifty, under the fixed gazes of the diners, who sat staring hungrily at her every move. To accomplish this she had at her command a small wood-burning stove (with chimney, thank God), a pile of potatoes, noodles, rice, some eggs and cabbage, and several chang-happy porter assistants, who alternated washing dishes with breaking up chunks of yak dung for the fire. A difficult situation on the face of it, but the Sherpani was cool: she cooked the whole list of orders by memory, slicing and tossing potatoes into one pan, stuffing wood in the fire, flipping twenty pounds of noodles in midair like they were a single hotcake—all with the sureness and panache of an expert juggler. It was a kind of genius.

Two hours later those who had ordered the meals that came last in her strict sequence got their cabbage omelets on French fries, and the kitchen emptied out as many people went to bed. The rest of us settled down to more chang and chatter.

Then a trekker came back into the kitchen, so he could listen to his shortwave radio without bothering sleepers in the lodge’s single dorm room. He said he wanted to catch the news. We all stared at him in disbelief. “I need to find out how the dollar’s doing,” he explained. “Did you know it dropped eight percent last week?”

You meet all kinds in Nepal.

Actually it’s interesting to hear what you get on shortwave in the Himal, because depending on how the ionosphere is acting, almost anything will bounce in. That night we listened to the People’s Voice of Syria, for instance, and some female pop singer from Bombay, which perked up the porters. Then the operator ran across the BBC world news, which was not unusual—it could have been coming from Hong Kong, Singapore, Cairo, even London itself.

Through the hissing of the static the public-school voice of the reporter could barely be made out. “… British Everest Expedition of 1986 is now on the Rongbuk Glacier in Tibet, and over the next two months they expect to repeat the historic route of the attempts made in the twenties and thirties. Our correspondent to the expedition reports—” and then the voice changed to one even more staccato and drowned in static: “—the expedition’s principal goal of recovering the bodies of Mallory and Irvine, who were last seen near the summit in 1924, crackle, buzz… chances considerably improved by conversations with a partner of the Chinese climber who reported seeing a body on the North Face in 1980 bzzzzkrkrk!… description of the site of the finding sssssssss… snow levels very low this year, and all concerned feel chances for success are sssskrkssss.” The voice faded away in a roar of static.

Trevor looked around at us, eyebrows lifted. “Did I understand them to say that they are going to search for Mallory and Irvine’s bodies?”

A look of deep horror creased Mad Tom’s face. Marion wrinkled her nose as if her chang had turned to Tibetan tea. “I can’t believe it.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was an unexpected opportunity for Freds to put his plan into action ahead of schedule. He said, “Haven’t you heard about that? Why Kunga Norbu here is precisely the climber they’re talking about, the one who spotted a body on the North Face in 1980.”

“He is?” we all said.

“Yeah, you bet. Kunga was part of the Chinese expedition to the North Ridge in 1980, and he was up there doing reconnaissance for a direct route on the North Face when he saw a body.” Freds spoke to Kunga Norbu in Tibetan, and Kunga nodded and replied at some length. Freds translated for him: “He says it was a Westerner, wearing museum clothing, and he had clearly been there a long time. Here, he says he can mark it on a photo—” Freds got out his wallet and pulled a wad of paper from it. Unfolded, it revealed itself as a battered black-and-white photo of Everest as seen from the Tibetan side. Kunga Norbu studied it for a long time, talked it over with Freds, and then took a pencil from Freds and carefully made a circle on the photo.

“Why he’s circled half the North Face,” John pointed out. “It’s fooking useless.”

“Nah,” Freds said. “Look, it’s a little circle.”

“It’s a little photo, innit.”

“Well, he can describe the spot exactly—it’s up there on top of the Black Band. Anyway, someone has managed to get together an expedition to go looking for the bodies, or the body, whatever. Now Kunga slipped over to Nepal last year, so this expedition is going on secondhand information from his climbing buds. But that might be enough.”

“And if they find the bodies?”

“Well, I think they’re planning to take them down and ship them to London and bury them in Winchester Cathedral.”

The Brits stared at him. “You mean Westminster Abbey?” Trevor ventured.

“Oh that’s right, I always get those two mixed up. Anyway that’s what they’re going to do, and they’re going to make a movie out of it.”

I groaned at the thought. More video.

The four Brits groaned louder than I did. “That is rilly dis-gusting,” Marion said.

“Sickening,” John and Mad Tom agreed.

“It is a travesty, isn’t it?” Trevor said. “I mean those chaps belong up there if anybody does. It’s nothing less than grave robbing!”

And his three companions nodded. On one level they were joking, making a pretense of their outrage; but underneath that, they were dead serious. They meant it.

V

To understand why they would care so much, you have to understand what the story of Mallory and Irvine means to the British soul. Climbing has always been more important there than in America—you could say that the British invented the sport in Victorian times, and they’ve continued to excel in it since then, even after World War Two when much else there fell apart. You could say that climbing is the Rolls Royce of British sport. Whymper, Hillary, the brilliant crowd that climbed with Bonington in the seventies: they’re all national heroes.

But none more so than Mallory and Irvine. Back in the twenties and thirties, you see, the British had a lock on Everest, because Nepal was closed to foreigners, and Tibet was closed to all but the British, who had barged in on them with Younghusband’s campaign back in 1904. So the mountain was their private playground, and during those years they made four or five attempts, all of them failures, which is understandable: they were equipped like Boy Scouts, they had to learn high-altitude technique on the spot, and they had terrible luck with weather.

The try that came closest was in 1924. Mallory was its lead climber, already famous from two previous attempts. As you may already know, he was the guy who replied “Because it’s there” when asked why anyone would want to climb the thing. This is either a very deep or a very stupid answer, depending on what you think of Mallory. You can take your pick of interpretations; the guy has been psychoanalyzed into the ground. Anyway, he and his partner Irvine were last glimpsed, by another expedition member, just eight hundred feet and less than a quarter of a mile from the summit—and at one P.M., on a day that had good weather except for a brief storm, and mist that obscured the peak from the observers below. So they either made it or they didn’t; but something went wrong somewhere along the line, and they were never seen again.

A glorious defeat, a deep mystery: this is the kind of story that the English just love, as don’t we all. All the public-school virtues wrapped into one heroic Tale—you couldn’t write it better. To this day the story commands tremendous interest in England, and this is doubly true among people in the climbing community, who grew up on the story, and who still indulge in a lot of speculation about the two men’s fate, in journal articles and pub debates and the like. They love that story.

Thus to go up there, and find the bodies, and end the mystery, and cart the bodies off to England… You can see why it struck my drinking buddies that night as a kind of sacrilege. It was yet another modern PR stunt—a money-grubbing plan made by some publicity hound—a Profaning of the Mystery. It was, in fact, a bit like videotrekking. Only worse. So I could sympathize, in a way.

VI

I tried to think of a change of subject, to distract the Brits. But Freds seemed determined to fire up their distress. He poked his finger onto the folded wreck of a photo. “You know what y’all oughta do,” he told them in a low voice. “You mentioned getting lost and climbing Pumori? Well shit, what you oughta do instead is get lost in the other direction, and beat that expedition to the spot, and hide old Mallory. I mean here you’ve got the actual eyewitness right here to lead you to him! Incredible! You could bury Mallory in rocks and snow and then sneak back down. If you did that, they’d never find him!”

All the Brits stared at Freds, eyes wide. Then they looked at each other, and their heads kind of lowered together over the table. Their voices got soft. “He’s a genius,” Trevor breathed.

“Uh, no,” I warned them. “He’s not a genius.” Laure was shaking his head. Even Kunga Norbu was looking doubtful.

Freds looked over the Brits at me and waggled his eyebrows vigorously, as if to say: this is a great idea! Don’t foul it up!

“What about the Lho La?” John asked. “Won’t we have to climb that?”

“Piece of cake,” Freds said promptly.

“No,” Laure protested. “Not piece cake! Pass! Very steep pass!”

“Piece of cake,” Freds insisted. “I climbed it with those West Ridge direct guys a couple years ago. And once you top it you just slog onto the West Shoulder and there you are with the whole North Face, sitting right off to your left.”

“Freds,” I said, trying to indicate that he shouldn’t incite his companions to such a dangerous, not to mention illegal, climb. “You’d need a lot more support for high camps than you’ve got. That circle there is pretty damn high on the mountain.”

“True,” Freds said immediately. “It’s pretty high. Pretty damn high. You can’t get much higher.”

Of course to people like the Brits this was only another incitement, as I should have known.

“You’d have to do it like Woody Sayres did back in ’62,” Freds went on. “They got Sherpas to help them up the Nup La over by Cho Oyo, then bolted to Everest when they were supposed to be climbing Gyachung Kang. They moved a single camp with them all the way to Everest, and got back the same way. Just four of them, and they almost climbed it. And the Nup La is twenty miles farther away from Everest than the Lho La. The Lho La’s right there under it.”

Mad Tom knocked his glasses up his nose, pulled out a pencil and began to do calculations on the table. Marion was nodding. Trevor was refilling all our glasses with chang. John was looking over Mad Tom’s shoulder and muttering to him; apparently they were in charge of supplies.

Trevor raised his glass. “Right then,” he said. “Are we for it?”

They all raised their glasses. “We’re for it.”

They were toasting the plan, and I was staring at them in dismay, when I heard the door creak and saw who was leaving the kitchen. “Hey!”

I reached out and dragged Arnold McConnell back into the room. “What’re you doing here?”

Arnold shifted something behind his back. “Nothing, really. Just my nightly glass of milktea, you know…”

“It’s him!” Marion exclaimed. She reached behind Arnold and snatched his camera from behind his back; he tried to hold on to it, but Marion was too strong for him. “Spying on me again, were you? Filming us from some dark corner?”

“No no,” Arnold said. “Can’t film in the dark, you know.”

“Film in tent,” Laure said promptly. “Night.”

Arnold glared at him.

“Listen, Arnold,” I said. “We were just shooting the bull here you know, a little private conversation over the chang. Nothing serious.”

“Oh, I know,” Arnold assured me. “I know.”

Marion stood and stared down at Arnold. They made a funny pair—her so long and rangy, him so short and tubby. Marion pushed buttons on the camera until the videocassette popped out, never taking her eye from him. She could really glare. “I suppose this is the same film you used this morning, when you filmed me taking my shower, is that right?” She looked at us. “I was in the little shower box they’ve got across the way, and the tin with the hot water in it got plugged at the bottom somehow. I had the door open a bit so I could stretch up and fiddle with it, when suddenly I noticed this pervert filming me!” She laughed angrily. “I bet you were quite pleased with that footage, weren’t you, you peeping Tom!”

“I was just leaving to shoot yaks,” Arnold explained rapidly, staring up at Marion with an admiring gaze. “Then there you were, and what was I supposed to do? I’m a filmmaker, I film beautiful things. I could make you a star in the States,” he told her earnestly. “You’re probably the most beautiful climber in the world.”

“And all that competition,” Mad Tom put in.

I was right about Marion’s reaction to a compliment of that sort—she blushed to the roots, and considered punching him too—she might have, if they’d been alone.

“—adventure films back in the States, for PBS and the ski resort circuit,” Arnold was going on, chewing his cigar and rolling his eyes as Marion took the cartridge over toward the stove.

The Sherpani waved her off. “Smell,” she said.

Marion nodded and took the videocassette in her hands. Her forearms tensed, and suddenly you could see every muscle. And there were a lot of them, too, looking like thin bunched wires under the skin. We all stared, and instinctively Arnold raised his camera to his shoulder before remembering it was empty. That fact made him whimper, and he was fumbling at his jacket pocket for a spare when the cassette snapped diagonally and the videotape spilled out. Marion handed it all to the Sherpani, who dumped it in a box of potato peels, grinning.

We all looked at Arnold. He chomped his cigar, shrugged. “Can’t make you a star that way,” he said, and gave Marion a soulful leer. “Really, you oughta give me a chance, you’d be great. Such presence.”

“I would appreciate it if you would now leave,” Marion told him, and pointed at the door.

Arnold left.

“That guy could be trouble,” Freds said.

VII

Freds was right about that.

But Arnold was not the only source of trouble. Freds himself was acting a bit peculiar, I judged. Still, when I thought of the various oddities in his recent behavior—his announcement that his friend Kunga Norbu was a tulku, and now this sudden advocacy of a Save Mallory’s Body campaign—I couldn’t put it all together. It didn’t make sense.

So when Freds’s party and my trekking group took off upvalley from Pheriche on the same morning, I walked with Freds for a while. I wanted to ask him some questions. But there were a lot of people on the trail, and it was hard to get a moment to ourselves.

As an opener I said, “So, you’ve got a woman on your team.”

“Yeah, Marion’s great. She’s probably the best climber of us all. And incredibly strong. You know those indoor walls they have in England, for practicing?”

“No.”

“Well, the weather is so bad there, and the climbers are such fanatics, that they’ve built these thirty- and forty-foot walls inside gyms, and covered them with concrete and made little handholds.” He laughed. “It looks dismal—scuzzy old gym with bad light and no heating, and all these guys stretched out on a concrete wall like a new kind of torture… Anyway I visited one of these, and they set me up in a race with Marion, up the two hardest pitches. Maybe 5.13 in places, impossible stuff. Everyone started betting on us, and the rule was someone had to top out for anyone to collect on the bets. But there was a leak getting the wall damp, and I came off about halfway up. So she won, but to collect the bets she had to top out. With the leak it really was impossible, but everyone who had bet on her was yelling at her to do it, so she just grit her teeth and started making these moves, man”—Freds illustrated in the air between us as we hiked—“and she was doing them in slow motion so she wouldn’t come off. Just hanging there by her fingertips and toes, and I swear to God she hung on that wall for must’ve been three hours. Everyone else stopped climbing to watch. Guys were going home—guys were begging her to come off—guys had tears in their eyes. Finally she topped out and crawled over to the ladder and came down, and they mobbed her. They were ready to make her queen. In fact she pretty much is queen, as far as the English climbers are concerned—you could bring the real one in and if Marion were there they wouldn’t even notice.”

Then Arnold slipped between us, looking conspiratorial. “I think this Mallory scheme is a great idea,” he whispered through clenched teeth. “I’m totally behind you, and it’ll make a great movie.”

“You miss the point,” I said to him.

“We ain’t doing nothing but climb Lingtren,” Freds said to him.

Arnold frowned, tucked his chin onto his chest, chewed his cigar. Frowning, Freds left to catch up with his group, and they soon disappeared ahead. So I lost my chance to talk to him.

We came to the upper end of Pheriche’s valley, turned right and climbed to get into an even higher one. This was the valley of the Khumbu Glacier, a massive road of ice covered with a chaos of gray rubble and milky blue melt ponds. We skirted the glacier and followed a trail up its lateral moraine to Lobuche, which consists of three teahouses and a tenting ground. The next day we hiked on upvalley to Gorak Shep.

Now Gorak Shep (“Dead Crow”) is not the kind of place you see on posters in travel agencies. It’s just above seventeen thousand feet, and up there the plant life has about given up. It’s just two ragged little teahouses under a monstrous rubble hill, next to a gray glacial pond, and all in all it looks like the tailings of an extraordinarily large gravel mine.

But what Gorak Shep does have is mountains. Big snowy mountains, on all sides. How big? Well, the wall of Nuptse, for instance, stands a full seven thousand feet over Gorak Shep. An avalanche we saw, sliding down a fraction of this wall and sounding like thunder, covered about two World Trade Centers’ worth of height, and still looked tiny. And Nuptse is not as big as some of the peaks around it. So you get the idea.

Cameras can never capture this kind of scale, but you can’t help trying, and my crowd tried for all they were worth in the days we were camped there. The ones handling the altitude well slogged up to the top of Kala Pattar (“Black Hill”), a local walker’s peak which has a fine view of the Southwest Face of Everest. The day after that, Heather and Laure led most of the same people up the glacier to Everest Base Camp, while the rest of us relaxed. Everest Base Camp, set by the Indian Army this season, was basically a tent village like ours, but there are some fine seracs and ice towers to be seen along the way, and when they returned the clients seemed satisfied.

So I was satisfied too. No one had gotten any bad altitude sickness, and we would be starting back the next morning. I was feeling fine, sitting up on the hill above our tents in the late afternoon, doing nothing.

But then Laure came zipping down the trail from Base Camp, and when he saw me he came right over. “George George,” he called out as he approached.

I stood as he reached me. “What’s up?”

“I stay talk friends porter Indian Army base camp, Freds find me Freds say his base camp come please you. Climb Lho La find man camera come hire Sherpas finish with Freds, very bad follow Freds.”

Now Laure’s English is not very good, as you may have noticed. But after all we were in his country speaking my language—and for him English came after Sherpa, Nepali, and some Japanese and German, and how many languages do you speak?

Besides, I find I always get the gist of what Laure says, which is not something you can always say of all our fellow native speakers. So I cried out, “No! Arnold is following them?”

“Yes,” Laure said. “Very bad. Freds say come please get.”

“Arnold hired their Sherpas?”

Laure nodded. “Sherpas finish porter, Arnold hire.”

“Damn him! We’ll have to climb up there and get him!”

“Yes. Very bad.”

“Will you come with me?”

“Whatever you like.”

I hustled to our tents to get together my climbing gear, and tell Heather what had happened. “How did he get up there?” she asked. “I thought he was with you all day.”

“He told me he was going with you! He probably followed you guys all the way up, and kept on going. Don’t worry about it, it’s not your fault. Take the group back to Namche starting tomorrow, and we’ll catch up with you.” She nodded, looking worried.

Laure and I took off. Even going at Laure’s pace we didn’t reach Freds’s base camp until the moon had risen.

Their camp was now only a single tent in a bunch of trampled snow, just under the steep headwall of the Khumbu Valley—the ridge that divided Nepal from Tibet. We zipped open the tent and woke Freds and Kunga Norbu.

“All right!” Freds said. “I’m glad you’re here! Real glad!”

“Give me the story,” I said.

“Well, that Arnold snuck up here, apparently.”

“That’s right.”

“And our Sherpas were done and we had paid them, and I guess he hired them on the spot. They have a bunch of climbing gear, and we left fixed ropes up to the Lho La, so up they came. I tell you I was pretty blown away when they showed up in the pass! The Brits got furious and told Arnold to go back down, but he refused and, well, how do you make someone do something they don’t want to up there? If you punch him out he’s likely to have trouble getting down! So Kunga and I came back to get you and found Laure at Base Camp, and he said he’d get you while we held the fort.”

“Arnold climbed the Lho La?” I said, amazed.

“Well, he’s a pretty tough guy, I reckon. Didn’t you ever see that movie he made of the kayak run down the Baltoro? Radical film, man, really it’s up there with The Man Who Skied Down Everest for radicalness. And he’s done some other crazy things too, like flying a hang glider off the Grand Teton, filming all the way. He’s tougher than he looks. I think he just does the Hollywood sleaze routine so he can get away with things. Anyway those are some excellent climbing Sherpas he’s got, and with them and the fixed ropes he just had to gut it out. And I guess he acclimatizes well, because he was walking around up there like he was at the beach.”

I sighed. “That is one determined filmmaker.”

Freds shook his head. “The guy is a leech. He’s gonna drive the Brits bats if we don’t haul his ass back down here.”

VIII

So the next day the four of us started the ascent of the Lho La, and were quickly engaged in some of the most dangerous climbing I’ve ever done. Not the most technically difficult—the Brits had left fixed rope in the toughest sections, so our progress was considerably aided. But it was still dangerous, because we were climbing an icefall, which is to say a glacier on a serious tilt.

Now a glacier as you know is a river of ice, and like its liquid counterparts it is always flowing downstream. Its rate of flow is much slower, but it isn’t negligible, especially when you’re standing on it. Then you often hear creaks, groans, sudden cracks and booms, and you feel like you’re on the back of a living creature.

Put that glacier on a hillside and everything is accelerated; the living creature becomes a dragon. The ice of the glacier breaks up into immense blocks and shards, and these shift regularly, then balance on a point or edge, then fall and smash to fragments, or crack open to reveal deep fissures. As we threaded our way up through the maze of the Lho La’s icefall, we were constantly moving underneath blocks of ice that looked eternal but were actually precarious—they were certain to fall sometime in the next month or two. I’m not expert at probability theory, but I still didn’t like it.

“Freds,” I complained. “You said this was a piece of cake.”

“It is,” he said. “Check out how fast we’re going.”

“That’s because we’re scared to death.”

“Are we? Hey, it must be only forty-five degrees or so.”

This is as steep as an icefall can get before the ice all falls downhill at once. Even the famous Khumbu Icefall, which we now had a fantastic view of over to our right, fell at only about thirty degrees. The Khumbu Icefall is an unavoidable part of the standard route on Everest, and it is by far the most feared section; more people have died there than anywhere else on the mountain. And the Lho La is worse than the Khumbu!

So I had some choice words for our situation as we climbed very quickly indeed, and most of them left Laure mystified. “Great, Freds,” I shouted at him. “Real piece of cake all right!”

“Lot of icing, anyway,” he said, and giggled. This under a wall that would flatten him like Wile E. Coyote if it fell. I shook my head.

“What do you think?” I said to Laure.

“Very bad,” Laure said. “Very bad, very dangerous.”

“What do you think we should do?”

“Whatever you like.”

We hurried.

Now I like climbing as much as anybody, almost, but I am not going to try to claim to you that it is an exceptionally sane activity. That day in particular I would not have been inclined to argue the point. The thing is, there is danger and there is danger. In fact climbers make a distinction, between objective danger and subjective danger. Objective dangers are things like avalanches and rockfall and storms, that you can’t do anything about. Subjective dangers are those incurred by human error—putting in a bad hold, forgetting to fasten a harness, that sort of thing. See, if you are perfectly careful, then you can eliminate all the subjective dangers. And when you’ve eliminated the subjective dangers, you have only the objective dangers to face. So you can see it’s very rational.

On this day, however, we were in the midst of a whole wall of objective dangers, and it made me nervous. We pursued the usual course in such a case, which is to go like hell. The four of us were practically running up the Lho La. Freds, Kunga and Laure were extremely fast and strong, and I am in reasonable shape myself; plus I get the benefits of more adrenaline than less imaginative types. So we were hauling buns.

Then it happened. Freds was next to me, on a rope with Kunga Norbu, and Kunga was the full rope length away—about twenty yards—leading the way around a traverse that went under a giant serac, which is what they call the fangs of blue ice that protrude out of an icefall, often in clusters. Kunga was right underneath this serac when without the slightest warning it sheared off and collapsed, shattering into a thousand pieces.

I had reflexively sucked in a gasp and was about to scream when Kunga Norbu jostled my elbow, nearly knocking me down. He was wedged in between Freds and me, and the rope tying them together was flapping between our legs.

Trying to revise my scream I choked, gasped for breath, choked again. Freds slapped me on the back to help. Kunga was definitely there, standing before us, solid and corporeal. And yet he had been under the serac! The broken pieces of the ice block were scattered before us, fresh and gleaming in the afternoon sun. The block had sheared off and collapsed without the slightest quiver or warning—there simply hadn’t been time to get out from under it!

Freds saw the look on my face, and he grinned feebly. “Old Kunga Norbu is pretty fast when he has to be.”

But that wasn’t going to do. “Ga gor nee,” I said—and then Freds and Kunga were holding me up. Laure hurried up to join us, round-eyed with apprehension.

“Very bad,” he said.

“Gar,” I attempted, and couldn’t go on.

“All right, all right,” Freds said, soothing me with his gloved hands. “Hey, George. Relax.”

“He,” I got out, and pointed at the remains of the serac, then at Kunga.

“I know,” Freds said, frowning. He exchanged a glance with Kunga, who was watching me impassively. They spoke to each other in Tibetan. “Listen,” Freds said to me. “Let’s top the pass and then I’ll explain it to you. It’ll take a while, and we don’t have that much day left. Plus we’ve got to find a way around these ice cubes so we can stick to the fixed ropes. Come on, buddy.” He slapped my arm. “Concentrate. Let’s do it.”

So we started up again, Kunga leading as fast as before. I was still in shock, however, and I kept seeing the collapse of the serac, with Kunga under it. He just couldn’t have escaped it! And yet there he was up above us, jumaring up the fixed ropes like a monkey scurrying up a palm.

It was a miracle. And I had seen it. I had a hell of a time concentrating on the rest of that day’s climb.

IX

Just before sunset we topped the Lho La, and set our tent on the pass’s flat expanse of deep hard snow. It was one of the spacier campsites I had ever occupied: on the crest of the Himalaya, in a broad saddle between the tallest mountain on earth, and the very spiky and beautiful Lingtren. Below us to one side was the Khumbu Glacier; on the other was the Rongbuk Glacier in Tibet. We were at about twenty thousand feet, and so Freds and his friends had a long way to go before reaching old Mallory. But nothing above would be quite as arbitrarily dangerous as the icefall. As long as the weather held, that is. So far they had been lucky; it was turning out to be the driest October in years.

There was no sign of either the British team or Arnold’s crew, except for tracks in the snow leading around the side of the West Shoulder and disappearing. So they were on their way up. “Damn!” I said. “Why didn’t they wait?” Now we had more climbing to do, to catch Arnold.

I sat on my groundpad on the snow outside the tent. I was tired. I was also very troubled. Laure was getting the stove to start. Kunga Norbu was off by himself, sitting in the snow, apparently meditating on the sight of Tibet. Freds was walking around singing “Wooden Ships,” clearly in heaven. “ ‘Talkin’ about ver-y free—and eeea-sy’—I mean is this a great campsite or what,” he cried to me. “Look at that sunset! It’s too much, too much. I wish we’d brought some chang with us. I do have some hash, though. George, time to break out the pipe, hey?”

I said, “Not yet, Freds. You get over here and tell me what the hell happened down there with your buddy Kunga. You promised you would.”

Freds stood looking at me. We were in shadow—it was cold, but windless—the sky above was clear, and a very deep dark blue. The airy roar of the stove starting was the only sound.

Freds sighed, and his expression got as serious as it ever got: one eye squinted shut entirely, forehead furrowed, and lips squeezed tightly together. He looked over at Kunga, and saw he was watching us. “Well,” he said after a while. “You remember a couple of weeks ago when we were down at Chimoa getting drunk?”

“Yeah?”

“And I told you Kunga Norbu was a tulku.”

I gulped. “Freds, don’t give me that again.”

“Well,” he said. “It’s either that or tell you some kind of a lie. And I ain’t so good at lying, my face gives me away or something.”

“Freds, get serious!” But looking over at Kunga Norbu, sitting in the snow with that blank expression, those weird black eyes, I couldn’t help but wonder.

Freds said, “I’m sorry, man, I really am. I don’t mean to blow your mind like this. But I did try to tell you before, you have to admit. And it’s the simple truth. He’s an honest-to-God tulku. First incarnation the famous Tsong Khapa, born in 1555. And he’s been around ever since.”

“So he met George Washington and like that?”

“Well, Washington didn’t go to Tibet, so far as I know.”

I stared at him. He shuffled about uncomfortably. “I know it’s hard to take, George. Believe me. I had trouble with it myself, at first. But when you study under Kunga Norbu for a while, you see him do so many miraculous things, you can’t help but believe.”

I stared at him some more, speechless.

“I know,” Freds said. “The first time he pulls one of his moves on you, it’s a real shock. I remember my first time real well. I was hiking with him from the hidden Rongbuk to Namche, we went right over Lho La like we did today, and right around Base Camp we came across this Indian trekker who was turning blue. He was clearly set to die of altitude sickness, so Kunga and I carried him down between us to Pheriche, which was already a long day’s work as you know. We took him to the Rescue Station and I figured they’d put him in the pressure tank they’ve got there, have you seen it? They’ve got a tank like a miniature submarine in their back room, and the idea is you stick a guy with altitude sickness in it and pressurize it down to sea level pressure, and he gets better. It’s a neat idea, but it turns out that this tank was donated to the station by a hospital in Tokyo, and all the instructions for it are in Japanese, and no one at the station reads Japanese. Besides as far as anyone there knows it’s an experimental technique only, no one is quite sure if it will work or not, and nobody there is inclined to do any experimenting on sick trekkers. So we’re back to square one and this guy was sicker than ever, so Kunga and I started down towards Namche, but I was getting tired and it was really slow going, and all of a sudden Kunga Norbu picked him up and slung him across his shoulders, which was already quite a feat of strength as this Indian was one of those pear-shaped Hindus, a heavy guy—and then Kunga just took off running down the trail with him! I hollered at him and ran after him trying to keep up, and I tell you I was zooming down that trail, and still Kunga ran right out of sight! Big long steps like he was about to fly! I couldn’t believe it!”

Freds shook his head. “That was the first time I had seen Kunga Norbu going into lung-gom mode. Means mystic long-distance running, and it was real popular in Tibet at one time. An adept like Kunga is called a lung-gom-pa, and when you get it down you can run really far really fast. Even levitate a little. You saw him today—that was a lung-gom move he laid on that ice block.”

“I see,” I said, in a kind of daze. I called out to Laure, still at the stove: “Hey Laure! Freds says Kunga Norbu is a tulku!”

Laure smiled, nodded. “Yes, Kunga Norbu Lama very fine tulku!”

I took a deep breath. Over in the snow Kunga Norbu sat cross-legged, looking out at his country. Or somewhere. “I think I’m ready for that hash pipe,” I told Freds.

X

It took us two days to catch up to Arnold and the Brits, two days of miserable slogging up the West Shoulder of Everest. Nothing complicated here: the slope was a regular expanse of hard snow, and we just put on the crampons and ground on up it. It was murderous work. Not that I could tell with Freds and Laure and Kunga Norbu. There may be advantages to climbing on Everest with a tulku, a Sherpa long-distance champion, and an American space cadet, but longer rest stops are not among them. Those three marched uphill as if paced by Sousa marches, and I trailed behind huffing and puffing, damning Arnold with every step.

Late on the second day I struggled onto the top of the West Shoulder, a long snowy divide under the West Ridge proper. By the time I got there Freds and Laure already had the tent up, and they were securing it to the snow with a network of climbing rope, while Kunga Norbu sat to one side doing his meditation.

Farther down the Shoulder were the two camps of other teams, placed fairly close together as there wasn’t a whole lot of extra flat ground up there to choose from. After I had rested and drunk several cups of hot lemon drink, I said, “Let’s go find out how things stand.” Freds walked over with me.

As it turned out, things were not standing so well. The Brits were in their tent, waist deep in their sleeping bags and drinking tea. And they were not amused. “The man is utterly daft,” Marion said. She had a mild case of high-altitude throat, and any syllable she tried to emphasize disappeared entirely. “We’ve oyd outrunning him, but the Sherpas are good, and he oyy be strong.”

“A fooking leech he is,” John said.

Trevor grinned ferociously. His lower face was pretty sunburned, and his lips were beginning to break up. “We’re counting on you to get him back down, George.”

“I’ll see what I can do.”

Marion shook her head. “God knows we’ve tried, but it does no good whatever, he won’t listen, he just rattles on about making me a stee, I don’t know how to dee with that.” She turned red. “And none of these brave chaps will agree that we should just go over there and seize his bloody camera and throw it into Tibeee!”

The guys shook their heads. “We’d have to deal with the Sherpas,” Mad Tom said to Marion patiently. “What are we going to do, fight with them? I can’t even imagine it.”

“And if Mad Tom can’t imagine it,” Trevor said.

Marion just growled.

“I’ll go talk to him,” I said.

But I didn’t have to go anywhere, because Arnold had come over to greet us. “Hello!” he called out cheerily. “George, what a surprise! What brings you up here?”

I got out of the tent. Arnold stood before me, looking sunburned but otherwise all right. “You know what brings me up here, Arnold. Here, let’s move away a bit, I’m sure these folks don’t want to talk to you.”

“Oh, no, I’ve been talking to them every day! We’ve been having lots of good talks. And today I’ve got some real news.” He spoke into the tent. “I was looking through my zoom over at the North Col, and I see they’ve set up a camp over there! Do you suppose it’s that expedition looking for Mallory’s body?”

Curses came from the tent.

“I know,” Arnold exclaimed. “Kind of puts the pressure on to get going, don’t you think? Not much time to spare.”

“Bugger off!”

Arnold shrugged. “Well, I’ve got it on tape if you want to see. Looked like they were wearing Helly-Hansen jackets, if that tells you anything.”

“Don’t tell me you can read labels from this distance,” I said.

Arnold grinned. “It’s a hell of a zoom lens. I could read their lips if I wanted to.”

I studied him curiously. He really seemed to be doing fine, even after four days of intense climbing. He looked a touch thinner, and his voice had an altitude rasp to it, and he was pretty badly sunburned under the stubble of his beard—but he was still chewing a whitened cigar between zinc-oxided lips, and he still had the same wide-eyed look of wonder that his filming should bother anybody. I was impressed; he was definitely a lot tougher than I had expected. He reminded me of Dick Bass, the American millionaire who took a notion to climb the highest mountains on each continent. Like Bass, Arnold was a middle-aged guy paying pros to take him up; and like Bass, he acclimatized well, and had a hell of a nerve.

So, there he was, and he wasn’t falling apart. I had to try something else. “Arnold, come over here a little with me, let’s leave these people in peace.”

“Good reee!” Marion shouted from inside the tent.

“That Marion,” Arnold said admiringly when we were out of earshot. “She’s really beautiful, I mean I really, really, really like her.” He struck his chest to show how smitten he was.

I glared at him. “Arnold, it doesn’t matter if you’re falling for her or what, because they definitely do not want you along for this climb. Filming them destroys the whole point of what they’re trying to do up there.”

Arnold seized my arm. “No it doesn’t! I keep trying to explain that to them. I can edit the film so that no one will know where Mallory’s body is. They’ll just know it’s up here safe, because four young English climbers took incredible risks to keep it free from the publicity hounds threatening to tear it away to London. It’s great, George. I’m a filmmaker, and I know when something will make a great movie, and this will make a great movie.”

I frowned. “Maybe it would, but the problem is this climb is illegal, and if you make the film, then the illegal part becomes known and these folks will be banned by the Nepali authorities. They’ll never be let into Nepal again.”

“So? Aren’t they willing to make that sacrifice for Mallory?”

I frowned. “For your movie, you mean. Without that they could do it and no one would be the wiser.”

“Well, okay, but I can leave their names off it or something. Give them stage names. Marion Davies, how about that?”

“That’s her real name.” I thought. “Listen, Arnold, you’d be in the same kind of trouble, you know. They might not ever let you back, either.”

He waved a hand. “I can get around that kind of thing. Get a lawyer. Or baksheesh, a lot of baksheesh.”

“These guys don’t have that kind of money, though. Really, you’d better watch it. If you press them too hard they might do something drastic. At the least they’ll stop you, higher up. When they find the body a couple of them will come back and stop you, and the other two bury the body, and you won’t get any footage at all.”

He shook his head. “I got lenses, haven’t I been telling you? Why I’ve been shooting what these four eat for breakfast every morning. I’ve got hours of Marion on film for instance,” he sighed, “and my God could I make her a star. Anyway I could film the burial from here if I had to, so I’ll take my chances. Don’t you worry about me.”

“I am not worrying about you,” I said. “Take my word for it. But I do wish you’d come back down with me. They don’t want you up here, and I don’t want you up here. It’s dangerous, especially if we lose this weather. Besides, you’re breaking your contract with our agency, which said you’d follow my instructions on the trek.”

“Sue me.”

I took a deep breath.

Arnold put a friendly hand to my arm. “Don’t worry so much, George. They’ll love me when they’re stars.” He saw the look on my face and stepped away. “And don’t you try anything funny with me, or I’ll slap some kind of kidnapping charge on you, and you’ll never guide a trek again.”

“Don’t tempt me like that,” I told him, and stalked back to the Brits’ camp.

I dropped into their tent. Laure and Kunga Norbu had joined them, and we were jammed in there. “No luck,” I said. They weren’t surprised.

“Superleech,” Freds commented cheerfully.

We sat around and stared at the blue flames of the stove.

Then, as usually happens in these predicaments, I said, “I’ve got a plan.”

It was relatively simple, as we didn’t have many options. We would all descend back to the Lho La, and maybe even down to Base Camp, giving Arnold the idea we had given up. Once down there the Brits and Freds and Kunga Norbu could restock at the Gorak Shep teahouses, and Laure and I would undertake to stop Arnold, by stealing his boots for instance. Then they could go back up the fixed ropes and try again.

Trevor looked dubious. “It’s difficult getting up here, and we don’t have much time, if that other expedition is already on the North Col.”

“I’ve got a better plan,” Freds announced. “Looky here, Arnold’s following you Brits, but not us. If we four pretended to go down, while you four took the West Ridge direct, then Arnold would follow you. Then we four could sneak off into the Diagonal Ditch, and pass you by going up the Hornbein Couloir, which is actually faster. You wouldn’t see us and we’d be up there where the body is, lickety-split.”

Well, no one was overjoyed at this plan. The Brits would have liked to find Mallory themselves, I could see. And I didn’t have any inclination to go any higher than we already had. In fact I was dead set against it.

But by now the Brits were absolutely locked onto the idea of saving Mallory from TV and Westminster Abbey. “It would do the job,” Marion conceded.

“And we might lose the leech on the ridge,” Mad Tom added. “It’s a right piece of work or so I’m told.”

“That’s right!” Freds said happily. “Laure, are you up for it?”

“Whatever you like,” Laure said, and grinned. He thought it was a fine idea. Freds then asked Kunga Norbu, in Tibetan, and reported to us that Kunga gave the plan his blessing.

“George?”

“Oh, man, no. I’d rather just get him down some way.”

“Ah come on!” Freds cried. “We don’t have another way, and you don’t want to let down the side, do you? Sticky wicket and all that?”

“He’s your fooking client,” John pointed out.

“Geez. Oh, man… Well… All right.”

I walked back to our tent feeling that things were really getting out of control. In fact I was running around in the grip of other people’s plans, plans I by no means approved of, made by people whose mental balance I doubted. And all this on the side of a mountain that had killed over fifty people. It was a bummer.

XI

But I went along with the plan. Next morning we broke camp and made as if to go back down. The Brits started up the West Ridge, snarling dire threats at Arnold as they passed him. Arnold and his Sherpas were already packed, and after giving the Brits a short lead they took off after them. Arnold was roped up to their leader Ang Rita, raring to go, his camera in a chest pack. I had to hand it to him—he was one tenacious peeping Tom.

We waved good-bye and stayed on the shoulder until they were above us, and momentarily out of sight. Then we hustled after them, and took a left into the so-called Diagonal Ditch, which led out onto the North Face.

We were now following the route first taken by Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld, in 1963. A real mountaineering classic, actually, which goes up what is now called the Hornbein Couloir. Get out any good photo of the North Face of Everest and you’ll see it—a big vertical crack on the right side. It’s a steep gully, but quite a bit faster than the West Ridge.

So we climbed. It was hard climbing, but not as scary as the Lho La. My main problem on this day was paranoia about the weather. Weather is no common concern on the side of Everest. You don’t say, “Why snow would really ruin the day.” Quite a number of people have been caught by storms on Everest and killed by them, including the guys we were going to look for. So whenever I saw wisps of cloud streaming out from the peak, I tended to freak. And the wind whips a banner of cloud from the peak of Everest almost continuously. I kept looking up and seeing that banner, and groaning. Freds heard me.

“Gee, George, you sound like you’re really hurting on this pitch.”

“Hurry up, will you?”

“You want to go faster? Well, okay, but I gotta tell you I’m going about as fast as I can.”

I believed that. Kunga Norbu was using ice axe and crampons to fire up the packed snow in the middle of the couloir, and Freds was right behind him; they looked like a roofer on a ladder. I did my best to follow, and Laure brought up the rear. Both Freds and Kunga had grins so wide and fixed that you’d have thought they were on acid. Their teeth were going to get sunburned they were loving it so much. Meanwhile I was gasping for air, and worrying about that summit banner.

It was one of the greatest climbing days of my life.

How’s that, you ask? Well… it’s hard to explain. But it’s something like this: when you get on a mountain wall with a few thousand feet of empty air below you, it catches your attention. Of course part of you says oh my God, it’s all over. Whyever did I do this! But another part sees that in order not to die you must pretend you are quite calm, and engaged in a semi-theoretical gymnastics exercise intended to get you higher. You pay attention to the exercise like no one has ever paid attention before. Eventually you find yourself on a flat spot of some sort—three feet by five feet will do. You look around and realize that you did not die, that you are still alive. And at that point this fact becomes really exhilarating. You really appreciate being alive. It’s a sort of power, or a privilege granted you, in any case it feels quite special, like a flash of higher consciousness. Just to be alive! And in retrospect, that paying attention when you were climbing—you remember that as a higher consciousness too.

You can get hooked on feelings like those; they are the ultimate altered state. Drugs can’t touch them. I’m not saying this is real healthy behavior, you understand. I’m just saying it happens.

For instance, at the end of this particular intense day in the Hornbein Couloir, the four of us emerged at its top, having completed an Alpine-style blitz of it due in large part to Kunga Norbu’s inspired leads. We made camp on a small flat knob top just big enough for our tent. And looking around—what a feeling! It really was something. There were only four or five mountains in the world taller than we were in that campsite, and you could tell. We could see all the way across Tibet, it seemed. Now Tibet tends mostly to look like a freeze-dried Nevada, but from our height it was range after range of snowy peaks, white on black forever, all tinted sepia by the afternoon sun. It seemed the world was nothing but mountains.

Freds plopped down beside me, idiot grin still fixed on his face. He had a steaming cup of lemon drink in one hand, his hash pipe in the other, and he was singing “ ‘What a looong, strange trip it’s been.’ ” He took a hit from the pipe and handed it to me.

“Are you sure we should be smoking up here?”

“Sure, it helps you breathe.”

“Come on.”

“No, really. The nerve center that controls your involuntary breathing shuts down in the absence of carbon dioxide, and there’s hardly any of that up here, so the smoke provides it.”

I decided that on medical grounds I’d better join him. We passed the pipe back and forth. Behind us Laure was in the tent, humming to himself and getting his sleeping bag out. Kunga Norbu sat in the lotus position on the other side of the tent, intent on realms of his own. The world, all mountains, turned under the sun.

Freds exhaled happily. “This must be the greatest place on earth, don’t you think?”

That’s the feeling I’m talking about.

XII

We had a long and restless night of it, because it’s harder than hell to sleep at that altitude. Sleepiness seems to go right out of the mental repertoire, and when it does arrive, you fall into what is called Cheyne-Stokes breathing. Your body keeps getting fooled concerning how much oxygen it’s getting, so you hyperventilate for a while and then stop breathing entirely, for up to a minute at a time. This is not a comforting pattern if it is going on in a sleeping person lying next to you; Freds for instance really got into it, and I kept waking up completely during some really long silences, worrying that he had died. He apparently felt the same way about me, but didn’t have my patience, so that if I ever did fall asleep I was usually jerked back to consciousness by Freds tugging on my arm, saying “George, damn it, breathe! Breathe!”

But the next day dawned clear and windless once again, and after breakfasting and marveling at the view we headed along the top of the Black Band.

Our route was unusual, perhaps unique. The Black Band, harder than the layers of rock above and below it, sticks out from the generally smooth slope of the face, in a crumbly rampart. So in effect we had a sort of road to walk on. Although it was uneven and busted up, it was still twenty feet wide in places, and an easier place for a traverse couldn’t be imagined. There were potential campsites all over it.

Of course usually when people are at twenty-eight thousand feet on Everest, they’re interested in getting either higher or lower pretty quick. Since this rampway was level and didn’t facilitate any route whatsoever, it wasn’t much traveled. We might have been the first on it, since Freds said that Kunga Norbu had only looked down on it from above.

So we walked this high road, and made our search. Freds knocked a rock off the edge, and we watched it bounce down toward the Rongbuk Glacier until it became invisible, though we could still hear it. After that we trod a little more carefully. Still, it wasn’t long before we had traversed the face and were looking down the huge clean chute of the Great Couloir. Here the rampart ended, and to continue the traverse to the fabled North Ridge, where Mallory and Irvine were last seen, would have been ugly work. Besides, that wasn’t where Kunga Norbu had seen the body.

“We must have missed it,” Freds said. “Let’s spread out side to side, and check every little nook and cranny on the way back.” So we did, taking it very slowly, and ranging out to the edge of the rampart as far as we dared.

We were about halfway back to the Hornbein Couloir when Laure found it. He called out, and we approached.

“Well dog my cats,” Freds said, looking astonished.

The body was wedged in a crack, chest deep in a hard pack of snow. He was on his side, and curled over so that he was level with the rock on each side of the crack. His clothing was frayed, and rotting away on him; it looked like knit wool. The kind of thing you’d wear golfing in Scotland. His eyes were closed, and under a fraying hood his skin looked papery. Sixty years out in sun and storm, but always in below-freezing air, had preserved him strangely. I had the odd feeling that he was only sleeping, and might wake and stand.

Freds knelt beside him and dug in the snow a bit. “Look here—he’s roped up, but the rope broke.”

He held up an inch or two of unraveled rope—natural fibers, horribly thin—it made me shudder to see it. “Such primitive gear!” I cried.

Freds nodded briefly. “They were nuts. I don’t think he’s got an oxygen pack on either. They had it available, but he didn’t like to use it.” He shook his head. “They probably fell together. Stepped through a cornice maybe. Then fell down to here, and this one jammed in the crack while the other one went over the edge, and the rope broke.”

“So the other one is down in the glacier,” I said.

Freds nodded slowly. “And look—” He pointed above. “We’re almost directly under the summit. So they must have made the top. Or fallen when damned close to it.” He shook his head. “And wearing nothing but a jacket like that! Amazing.”

“So they made it,” I breathed.

“Well, maybe. Looks like it, anyway. So… which one is this?”

I shook my head. “I can’t tell. Early twenties, or mid-thirties?”

Uneasily we looked at the mummified features.

“Thirties,” Laure said. “Not young.”

Freds nodded. “I agree.”

“So it’s Mallory,” I said.