The two strands running through Clive Thurston's life are utterly incompatible. On the one hand is Carol, a rare bird in Hollywood, an actress with integrity and intelligence, and his own undistinguished literary output, a combination to bring him love, happiness and obscurity; on the other his fame, wealth and reputation-bringing play Rain Check, a one-off performance that cannot be repeated, and only Thurston knows why - and Eve.

Even Carol does not know of the torments Thurston suffers on account of Eve. The dreadful counterpoint approaches its climatic cadence, driving him to the brink of despair, as he faces professional ruin, degradation and death, until at last, modulating the Eve-theme, he seeks to lead the melody back to Carol.

Only James Hadley Chase could handle such a subject with such edge-of-chair assurance.

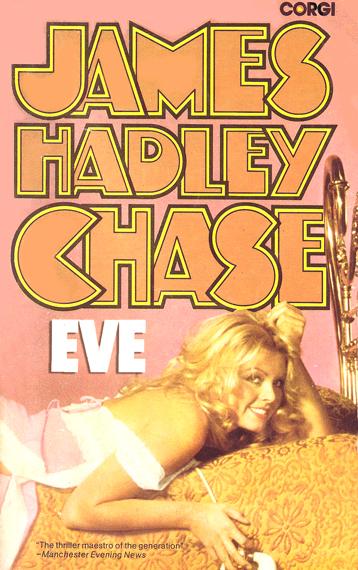

James Hadley Chase

Eve

1945

“I would find her throat with one hand and with the other I would switch on the little bedside lamp. Then would come the moment that would heal all the wounds she had inflicted on me. That brief moment when her senses would awake from sleep and her eyes would recognize me. She would know why I was there and what I was going to do. I would see the helpless, terrified look that would come into her eyes . . .

I would kill her quickly with my knee on her chest and my hands about her throat. Pinning her to the bed with my weight, she would not have a chance. No one would know who had done it. It could have been any of her men friends. . .”

CHAPTER ONE

BEFORE I begin to tell you the story of my association with Eve, I must first tell you, as briefly as possible, something about myself and the events that led up to our first meeting.

Had it not been for the extraordinary change in my life at the time when I had resigned myself to the mediocre career as a shipping clerk, I would not have met Eve, and consequently, I would not have endured an experience which was ultimately responsible for spoiling my life.

Although it is now two years since last I saw Eve, I have only to think of her to feel again the craving urge and angry frustration which kept me chained to her during a period when all my energies and attention should have been focused upon my work.

It does not matter what I am doing now. No one has ever heard of me in this Pacific coast town where I came nearly two years ago after I had realized what a worthless and elusive will-o-the-wisp I had been chasing.

But it is not the present nor the future that is important. My story is to do with the past.

Although I am anxious to bring Eve upon my stage without delay, there are a few details about myself, as I have said before, that first must be told.

My name is Clive Thurston. You may have heard of me. I was supposed to be the author of that sensationally successful play Rain Check. Although I did not, in fact, write the play I did write three novels which were, in their way, equally successful.

Before Rain Check was produced I was, as I am now, a nobody. I lived in Long Beach in a large apartment house near a fish cannery where I worked as a shipping clerk.

Until John Coulson came to stay at the apartment house I lived a monotonous and unambitious existence; the kind of life that hundreds of thousands of young men lead who have no prospects and who will be doing the same work in another twenty years’ time as they are doing now.

Although my life was monotonous and lonely I accepted it with apathetic resignation. I could see no escape from the routine of getting up in the morning, going to work, eating cheap meals, wondering whether I could afford this thing or that and having an occasional adventure with a woman if money allowed. There was no escape until I met John Coulson and even then it was not until he died that I saw my chance and took it.

John Coulson knew he was going to die. For three years he had been fighting tuberculosis and now he could fight no more. Like a dying animal who goes into hiding, he cut himself off from his friends and connections and came to live in the sordid apartment house in Long Beach.

There was something about him that attracted me and he seemed willing enough to share my company.

Perhaps it was because he was a writer. For a long time I had wanted to write, but the labour involved had always discouraged me. I felt that if I could once get started, my latent talents, which I was confident I possessed, would bring me fame and fortune. I suppose there are many of us who think like this, and like many of us, I lacked the initiative to begin.

John Coulson told me that he had written a play which, he assured me, was the finest thing he had ever done. I gladly listened to him, learning some surprisingly interesting things about the technique of play writing and the money that a good play will earn.

Two evenings before he died, he asked me to send his play to his agent. He was now bedridden and could do little to help himself.

“I don’t think I’ll live to see it produced,” he said moodily, staring out of the window. “God knows who’ll benefit, but that’s something my agent will have to arrange. It’s a damn funny thing, Thurston, but I have no one to leave anything to. I wish I had children now. It would have made all this work worth while.”

I asked him casually whether his agent was expecting the play and he shook his head. “No one but you knows that I’ve even written it.”

The following day was Saturday and the yearly Water Sports Carnival was being held at Alamitos Bay. I went down to the beach with the thousands of other weekenders to watch the yacht racing.

I disliked mixing with crowds, but it was obvious that Coulson was sinking and I felt I had to get away from the atmosphere of pending death that pervaded the house.

I arrived at the harbour as the tiny yachts were being prepared for the most important race of the afternoon. The prize was a gold cup, and competition ran high.

One particular yacht attracted my attention. She was a grand little boat with bright red sails and her lines were designed for speed. There were two men working on her. One, whom I gave only a cursory glance, was a typical longshoreman, but the other was obviously the owner. He was expensively dressed in white flannels and buckskin shoes and around his wrist I noticed a heavy gold bracelet. His big fleshy face had that arrogant expression which comes only from much wealth and power. He stood by the tiller, a cigar clamped between his teeth, watching the other man put the final touches to the boat. I wondered who he was and decided finally that he might either be a movie director or else an oil magnate.

After watching him for a few minutes, I moved away only to turn back at the sound of a heavy fall and a shout of alarm.

The longshoreman had slipped and was now lying on the harbour with a badly fractured leg.

The accident was immediately responsible for my extra-ordinary change of fortune. I had some experience of handling yachts and I volunteered to take the longshoreman’s place and by doing so I shared the honours with the owner of winning the gold cup.

It was only after the race that the owner of the yacht introduced himself to me. When he told me his name I did not at first realize my good fortune. Robert Rowan was, at that time, one of the most powerful men behind the Theatre Guild, He owned eight or nine theatres and he had a long string of theatrical successes behind him.

He was childishly pleased to have won the cup and embarrassingly grateful for my help. He gave me his card and solemnly promised that if there was anything he could do for me he would do it.

You can now probably see the temptation that lay ahead of me. On my return to the apartment I found Coulson was unconscious; the next day he was dead. His play, ready to be mailed to his agent, lay on my bureau. I did not hesitate for long. Coulson had admitted that he knew of no one who would benefit by the play and I had felt at the time that he might at least have thought of me. It took me only a few minutes to reason with my protesting conscience and then I opened the parcel and read the play.

Although I knew little about play writing, I realized when I had finished it, that the play was outstanding. I sat for a long time considering the chances of detection, but I could see no danger at all. Then before I went to bed I substituted a new title page and cover to the manuscript. Instead of Boomerang by John Coulson, the title page now read, Rain Check by Clive Thurston. The following day I sent the play to Rowan.

It was almost a year before Rain Check was produced. By that time many alterations had been made to the original script as Rowan liked to have his personality impressed upon any theatrical venture that he financed. But in that time, I had become quite used to the feeling that the play was mine and when it was finally produced, scoring an immediate success, I was genuinely proud of my achievement.

It is a great feeling to walk into a crowded room and have someone introduce you and see by the people’s faces that you mean something to them. Anyway, it meant a lot to me. It meant a lot too when I began to receive large sums of money, where previously I had to manage on forty dollars a week.

When I was assured that the play would enjoy a long run, I left New York for Hollywood. I felt that with my present reputation I should be in demand and perhaps establish myself as a top flight script writer. As I was now drawing almost two thousand dollars a week from royalties, I did not hesitate to take an apartment in a modern block off Sunset Boulevard.

Once I had settled down, I determined to exploit my opportunities and after considerable thought and planning I began work on a novel. It was a story of a man who had been hurt in the war and could not love his girl. I had known such a case and I knew what had happened to the girl. It was explosive material and it had made a big impression on me. Somehow I managed to get that impression over in the book. My name helped it, of course, but even at that, it wasn’t such a bad piece of work. It sold ninety-seven thousand copies and was still selling by the time my second book was on the market. This one was not so good, but it sold. It was my first attempt at creative writing which I found exceedingly difficult. My third novel was based on the lives of a married couple I knew intimately. The wife had behaved outrageously and I had felt very bad about the final break up. All I had to do was to sit at my typewriter. The book wrote itself and when it was published it scored an immediate success.

I was sure after this that I had the golden touch. I told myself that I could have succeeded without John Coulson’s play. I marvelled at my stupidity to have wasted so many years of my life on an office stool when I could have been writing and earning big money.

A few months later, I decided I would have to write a play. Rain Check had finished playing on Broadway and was now touring. It was still doing excellent business, but I knew that before long I would be receiving smaller royalties and I did not wish to lower my present standard of living. Besides that, my friends were asking me when I was going to write for the theatre again and my constant excuses were becoming threadbare.

When I began to plan a play I found I had no ideas that could be dramatized. I kept trying. I talked to people, but in Hollywood, no one gives away ideas. I thought and worried, but nothing came. Finally I said the hell with a play, and decided to write another novel. So I sat down at my typewriter and wrote another novel. I just cut into it and kept writing until I finished it. Then I sent it to my publisher.

Two weeks later, my publisher asked me to lunch. He was very direct and said bluntly that the book was no good. He did not have to convince me. I knew the book was no good the moment I had finished it. So I told him to forget the book. I explained that I had rushed it, that I had been constantly interrupted and that I would let him have something up to standard in a month or so.

I began to hunt for a place where I could work without interruption. I told myself that if I could get away from the mob that demanded my time and attention, if I could find some quiet spot with a good view so that I could get my nerves right, I would write another best seller, and even a great play. I was so sure of myself now that I was certain that, given the right surroundings, I could do really good work. Eventually I found a place that I felt was ideal in every way.

Three Point was a one storey cabin which lay back a few hundred yards from the road to Big Bear Lake. It had a wide porch and a magnificent view across the hills. It had been furnished with every conceivable luxury and a number of modern labour saving devices had been installed, including a small, but powerful generating plant. I was delighted to hire it for the summer.

I hoped that Three Point would be my salvation, but it didn’t work out that way. I would get up around nine o’clock and sit on the porch with a pot of strong coffee at my elbow and my typewriter before me. I would stare at the view and get nowhere. I would spend the morning smoking, looking at the view, writing a few lines and tearing them up. In the afternoon I would take the car over to Los Angeles, where I would wander around talking to the movie writers and watching the film stars. In the evening, I would try again, get irritated and finish off the evening by going to bed.

It was during this crisis of my career, when success or failure could be influenced by the slightest mental disturbance, that Eve came into my life. Her influence became so great that I was drawn to her as a pin is drawn to a giant magnet. She never knew the real extent of her power over me and if she had known, she would not have cared. Her arrogant indifference was the hardest part of her character I had to endure. Whenever I was with her, I had an overwhelming urge to obtain some moral surrender from her, to make her give up the secret strength that she had. The struggle between us was an infernal obsession with me.

But this is enough. My stage is set and my story can begin. I have long planned to write it. I have tried before and failed. This time I may succeed.

It may be that if this book is ever published, it will find its way into Eve’s hands. I can imagine her lying in bed, a cigarette between her fingers, reading what I have written. Because her life is peopled by so many unidentified men, who must inevitably be shadowy figures in her mind, she will have forgotten most, if not all, of the things we did together. It may interest her to re-live the futile moments of our association and it may also give her confidence in her strength and ability to continue to stand alone. At least, she will learn when she has reached the end of my story that I have probed deeper into her life than she imagined, and, in stripping some of the camouflage from her, I have also stripped myself.

And when she has reached the last page, I can imagine her, with that contemptuous, wooden expression on her face I have seen so often, tossing the book indifferently aside.

CHAPTER TWO

AT a gas station in San Bernardino, they told me there was a tornado warning out.

The attendant, in smart white overalls with a red triangular badge on his breast pocket, advised me to stay in San Bernardino for the night, but I wouldn’t listen.

When I got into the hills, it began to blow. I kept going and a mile further on the stars were blotted out and then torrential rain came down like a black steel curtain shutting in the night with mist and water.

All I could see through the half crescent clearing made by the wind-shield wiper was the rebounding rain on the car’s hood and a few feet of the shiny black road in the light of my headlights.

The noise of the wind and the rain against the car made me feel that I was imprisoned in a giant drum upon which some lunatic drummer was beating. All around me came the sound of trees falling and rocks shifting, and above all this, the noise of water against the wheels of the car. Rain flowed down the side windows and reflected my face, lit by the yellow light from the dashboard.

Then I nearly ran off the road. I had the hillside on my left and nothing but a clean drop into the valley on my right. My heart raced as I wrenched at the driving wheel and I fed more gas into the engine. The wind was so fierce that there was hardly any increase in the car’s speed. The needle of the speedometer flickered between ten and fifteen miles an hour which seemed to be the best speed I could squeeze out of the engine.

Coming slowly around the next bend, I saw two men standing in the middle of the road. They had lanterns and they wore black slickers that shone in the rain and lantern light.

I slowed down to a crawl as one of them came over.

“Why, hello, Mr. Thurston,” he said, rain from his hat dripping onto my sleeve, “Making for Three Point?”

I recognized him. “Hello, Tom,” I said. “Can I get through?”

“I don’t say you won’t make it.” His face was the colour of bruised meat from the wind and the rain. “It’ll be bad though. Maybe you’d better go back.”

I started the engine. “I’ll take a chance. Do you think the road’s open?”

“A big Packard went through two hours ago. It ain’t come back. Maybe it’s still all right, but you’d better watch out. The wind up there’ll be hell.”

“If a Packard can get through, I’m damned sure I can,” I said and wound up the window and drove on.

I drove around the next sharp bend and edged up the hill, keeping close to the mountain-side. A few more minutes’ driving brought me to the narrow mountain track that led through to Big Bear Lake.

The forest stopped abruptly at the foot of the track, and, except for a few jagged boulders on the mountainside, the rest of the track to Big Bear Lake was bare and exposed.

The wind crashed against the car as I drove out of the shelter of the trees. I felt the car rock. The outside wheels lifted a few inches before thudding back onto the road. I cursed. If that had happened when I was pulling around a bend, I would have been flung into the valley. I shifted into low gear and decreased my speed. Twice the car was brought to a standstill by a sudden gust of wind. Each time the engine stalled and I had to act quickly to stop from rolling backwards.

My nerves were badly frayed by the time I reached the crest of the hill. The rain drove against the windshield and I had to lean out of the window to see where I was going. The road was not more than twenty feet wide and I rounded the next bend more by luck than judgment with the the wind tearing at the car, shaking and lifting it. Once round the bend, I found shelter. The rain continued to drum on the roof of the car, but I felt easier knowing that the rest of the run was downhill, out of the wind.

Three Point was only a few miles further on and although I knew the worst part of the journey was over I continued to drive with caution. It was as well for, without warning, a stationary car suddenly appeared in my headlights and I only managed to slam on my brakes in time. The wheels locked and for one unpleasant moment, I thought I was going to skid off the road; then my bumpers hit the back of the other car and I was thrown forward against the driving wheel.

Cursing the fool who had left this car in the middle of the road without a warning light I stood on the running board of my car while I groped for my flashlight. Rain poured down on me and before stepping to the ground, I turned the light down to see where I was going. Water was up to my hub caps and sending the beam of the flashlight over to the other car, I now realized why it had been left like that. Water was up to the front wheels and had probably got into the distributor.;

I could not understand why there was a miniature lake in the road, which, I knew, went steeply downhill for the next few miles. Cautiously, I lowered myself into the water which rose to my calves. Gluey mud sucked at my shoes as I splashed over to the other car. By now, the rain had reduced my hat to irritating sogginess. Impatiently, I pulled it off and threw it away.

When I got over to the stationary car, I peered through the windows. It was empty. I climbed on its running board and worked my way towards the front of it so that I could see the road beyond. The beam from my flashlight showed me that the road had ceased to exist. Trees, boulders and mud completely blocked the track, forming a kind of dam.

The car was a Packard and I decided that this must be the car Tom had told me about.

There was nothing for me to do but walk. I went back to my car and lifted out the smaller of my two bags. I locked the car doors, climbed past the Packard and splashed through the water to the jungle of trees and rocks that blocked the road. Once out of the water, I continued to climb without difficulty. I soon reached the top of the rubble and could look down onto the road below which was, as far as I could see, clear of any further obstruction.

The climb down was more difficult and once I nearly fell. I had to drop my bag and clutch frantically at the roots of a tree to save myself and there was more delay before I found my bag again. But finally I reached the road.

Once past the obstruction, my progress was straightforward and in ten minutes or so, I reached the white gates of Three Point. I had not gone far up the drive before I saw a light in the sitting room. I immediately thought of the driver of the Packard and wondered a little angrily how he had got into the cabin.

I approached cautiously, anxious to catch a glimpse of my visitor before I made my own presence known. In the shelter of the porch, I put down my bag and peeled off my soaking wet bush jacket which I tossed onto the wooden bench against the log wall. I walked slowly to the window and looked into the lighted room. Whoever had broken into the cabin had lit a fire which blazed cheerfully. The room was empty, but as I stood hesitating, a man came in from the kitchen, carrying a bottle of my Scotch, two glasses and a syphon.

I looked at him with interest. He was short, but his chest and shoulders were powerful. He had mean blue eyes and the longest arms I had ever seen on anything more civilized than an orang-outang. I disliked him on sight.

He stood in front of the fire and measured out two stiff whiskies. One glass he put on the mantelpiece, the other he raised to his lips. He tasted the Scotch as if he were a connoisseur and was a little doubtful of this particular brand. I watched him roll the whisky round in his mouth, cock his head and eye the whisky thoughtfully. Then he nodded, apparently satisfied, and gulped down the rest of it. Having refilled his glass, he sat down in the armchair by the fire with the bottle on the table within reach.

I guessed he was on the wrong side of forty. He didn’t look like the kind of man to own a Packard. His suit was a little shabby and his taste in shirts, to judge from what he wore, was violent. I heartily disliked the prospects of spending the night in his company.

The second whisky on the mantelpiece also disturbed me. It could only mean that this intruder had a companion and I was in half a mind to remain where I was until this other person appeared. However, the wind and my wet clothes decided me. I wasn’t going to stand out there any longer. I picked up my bag and walked around to the front door. The door was locked. I took out my keys, opened the door noiselessly and entered the lobby. I put my bag down and as I stood hesitating, wondering whether to go into the sitting room and make myself known or to go straight to the bathroom, the man appeared at the sitting room door.

He stared at me in ugly surprise. “What the hell do you want?” His voice was coarse and rasping.

I looked him over. “Good evening. I hope I’m not in the Way, but I happen to own this place.”

I expected him to collapse like a pricked balloon, but he became even more aggressive. His mean little eyes snapped at me and two veins at his temples began to swell.

“You mean this is your cabin?” he demanded.

I nodded. “Don’t let it embarrass you. Have a drink — you’ll find whisky in the kitchen. I’ll run along and take a bath, but I’ll be right back.”

Leaving him staring blankly after me, I walked into my bed-room and shut the door. Then I became really infuriated.

Across the room, like stepping stones, lay various feminine garments; a black silk dress, lingerie, stockings, and finally at the bathroom door, a pair of black suede, mud-covered shoes.

A pigskin suitcase lay open on the bed from which spilled other feminine garments. A blue tailored dressing gown with short sleeves was draped over a chair before the electric heater.

I stood staring at this disorder, angry beyond words, but before I could do anything — I was on the point of walking into the bathroom and expressing an opinion of such bad manners — the bedroom door opened and the man came in.

I turned on him. “What’s all this?” I asked, waving my hands at the scattered garments on the floor and the confusion on the bed. “Did you imagine this was a hotel?”

He fingered his tie uneasily. “Now, don’t be sore. We found the place empty and—”

“All right, all right.” I snapped, fighting down my annoyance. It was really no use making a fuss. They happened to be unlucky that I had returned. “You certainly know how to make yourself at home,” I went on. “But never mind. I’m wet and irritable. It’s a hell of a night, isn’t it? Excuse me, I’ll use the spare bathroom.” I pushed past him and walked down the passage to the guest room.

“I’ll fix you a drink,” he called after me.

I liked that too. To have a stranger offer me my own Scotch is something I go for in a big way. I slammed the bedroom door and got out of my wet clothes.

After a hot bath, I felt better. After a shave, I felt sufficiently human to wonder what the woman would be like. But my mind recoiled when I thought of the man. If she were anything like him, I was in for an indescribable evening.

I put on a grey whipcord, fixed my hair and glanced at myself in the mirror. I did not look my forty years. Most people thought I was in my early thirties. All right, I was flattered by this. I’m as human as they come. I looked at my square jaw, my high cheekbones and the cleft in my chin. I was satisfied with what I saw. I was tall, rather on the thin side, but my suit fitted me excellently. I could still qualify as a distinguished playwright and novelist, although that was a tag a newspaper had yet to put on me.

I paused as I reached the sitting room door. The man’s voice came faintly through the panels of the door, but I could not hear what he was saying. Squaring my shoulders and settling the casual, disinterested expression on my face that I reserved for press meetings, I turned the knob and went in.

CHAPTER THREE

I SAW the woman, slight and dark haired, squatting on her heels before the fire. She had on the short-sleeved dressing gown that had been on the chair in my bedroom. Although she must have known that I had entered the room, she did not look round. As she held her hands towards the fire I saw her wedding ring. I also noticed that her shoulders were a shade wider than her hips and that is the way I like a woman to be built.

I did not mind her ignoring my entrance. I did not mind the wedding ring. But I did mind the dressing gown.

No woman looks her best in a dressing gown. Even if she did not know who I was, she might at least have dressed. It did not occur to me that she might not give a damn how she looked. I was judging her by the standards of the other women I knew. They would prefer me to see them naked than in a dressing gown.

With my reputation, looks and money, it was inevitable that women should spoil me. At first I enjoyed their attentions although I knew that the majority of them treated me as they treated any other elgible bachelor in Hollywood. They wanted me for my money, my name, my parties and for everything except myself.

Most women, if they had the right appeal, interested me, Good-looking, well-dressed women were an essential part of my background. They stimulated me, they were my recreation and they bolstered up my ego. I liked to have them around as some people like having good pictures on their walls. But, lately, they bored me. I found that my relations with them had developed into a series of strategical moves, in which both sides were expert, to obtain, on their part, the maximum entertainment, presents and attention, and on my part, a few hours of disillusioned rapture.

Carol was the one exception. We had met in New York when I was waiting for Rain Check to be produced. She was, at that time, Robert Rowan’s personal secretary. She liked me and, oddly enough, I liked her. It was she who had encouraged me to go to Hollywood where she was now working as script writer for International Pictures.

I doubt if I am capable of loving any woman for long. In a way, I suppose, I should be pitied for this, as obviously there must be many advantages in which seems to me to be the stale routine of having one woman at your side for the rest of your days. If there are no advantages, then why do so many people marry? I feel then, that I have been cheated of something because I am not like the ordinary man in the street.

There was a time, before I came to Hollywood, when I did seriously consider marrying Carol. I enjoyed her company and considered her more intelligent than any other woman I knew.

But Carol was busy at the Studios and we seldom met during the day. I had a lot of women on my hands and my time was taken up not only during the day, but most nights as well. Carol kidded me about those women, but she didn’t seem to mind. It was only when I was a little drunk one night and told her that I loved her that she gave herself away. She may have been a little drunk too, but I do not think so. For a couple of weeks, I felt like a heel when I went around with another woman, but after that, I stopped worrying. I supposed I became used to the idea that Carol loved me, in the same way as I became used to most things if they lasted long enough.

While I was looking at the woman, the man, who had been fixing drinks at the sideboard came over and gave me a Scotch and soda. He looked a little drunk and now that we were in a good light, I saw he needed a shave.

“I’m Barrow,” he said, breathing whisky fumes in my face. “Harvey Barrow. I’m certainly embarrassed busting in like this, but there was nothing else I could do.” He stood close to me, his thick set body between me and the woman by the fire.

I was not interested in him. I would not have noticed if he had dropped dead at my feet. I moved a few paces back so I could see the woman. She stayed by the fire as if she did not know I was in the room and oddly enough I found her attitude of deliberate indifference pleasantly exciting.

Barrow tapped my arm. I took my eyes off the woman and concentrated on him. He kept apologizing for breaking into my cabin so I told him curtly that it was all right and that I would have done the same thing myself if I had been in his place. Then casually I introduced myself, keeping my voice low so that the woman should not hear me. If she wanted to make an impression on me I would keep my identity from her to the last moment and then enjoy the look of dismay that would be certain to come when she realized whom she had been ignoring.

I had to repeat my name twice before he got it and, even then, it did not mean anything to him. I actually helped him by adding “the author’, but I could see he had never heard of me. He was the kind of stupid ignoramus who has never heard of anyone. From that moment I was through with him.

“Glad to meet you,” he said solemnly, shaking my hand. “It’s pretty nice of you not to get sore. Some guys would have kicked me out.”

Nothing would have pleased me more, but I said untruthfully. “That’s all right,” and looked past him at the woman. “Tell me, is your wife frigid, a deaf-mute or just coy?”

He followed my glance and his coarse, red face tightened.

“This puts me in a bit of a jam, ol’ boy,” he said, his voice a mumble in my ear. “She ain’t my wife and she’s as mad as hell. She got wet and a dame like her doesn’t like getting wet.”

“I see.” I felt suddenly disgusted. “Well, never mind. I want to meet her,” and I walked over to the fire and stood close to the woman.

She turned her head, looked at my feet and then looked abruptly up at me.

I smiled. “Hello,” I said.

“Hello,” she returned and looked back into the fire.

I had only one brief glance at her heart-shaped face with its firm mouth, stubborn chin and strangely disconcerting eyes. But it was enough. I had a sudden stiffled feeling, the kind of feeling you get when on top of a high mountain, and I knew what that meant.

It wasn’t that she was pretty. She was, if anything, plain, but there was something magnetic about her that stirred me. Perhaps magnetic was not quite the right word. I instinctively knew that behind her mask she was primitively bad and there was something almost animal in her make-up. Just to look at her was like getting a jolt of electricity.

I decided that, after all, the evening was not going to be so bad. In fact, it looked as if it were going to be exceedingly interesting.

“Won’t you have a drink?” I asked, hoping that she would look up again, but she didn’t. She lowered herself to the carpet and tucked her legs under her.

“I have one.” She pointed to the glass that stood near her in the hearth.

Barrow came over. “This is Eve . . . Eve . . .” and he floundered, his face reddening.

“Marlow,” the woman said, her fist clenched tightly in her lap.

“Yeah,” Barrow said quickly. “I’ve a lousy memory for names.” He looked at me and I could see he had already forgotten mine. I was not going to help him. If a man could , not remember the name of his mistress then to hell with him.

“So you got wet,” I said to the woman and laughed.

She looked up. I don’t believe in first impressions, but I knew she was a rebel. I knew she had a hell of a temper, swift, violent and uncontrolled. Although she was slight, her whole make-up — her eyes, the way she held herself, her expression — gave the impression of strength. She had two deep furrows above the bridge of her nose. They were responsible to some degree for the character in her face, and could only have come from worry and much suffering. I became intensely curious to know more about her.

“I did get wet,” she said and laughed too.

Her laugh startled me. It was unexpectedly pleasing as well as infectious. When she laughed, she glanced up and her expression altered, the hard lines went away and she looked younger. It was difficult to guess her age. Somewhere in the thirties; maybe thirty-eight, maybe thirty-three; when she laughed, she could have been twenty-five:

Barrow looked a little sick. He eyed us both suspiciously. He had reason. If he listened carefully he would have heard my glands working.

“I got wet too,” I said, sitting down in the armchair close to her. “If I’d known it was going to be as bad as this, I would have spent the night in San Bernadino. I’m certainly glad now I didn’t.” They both gave me a quick look. “Have you come far?”

There was a pause. Eve looked into the fire. Barrow rolled his glass between his thick fingers. You could almost hear him think.

“Los Angeles,” he said, at last.

“I get around Los Angeles quite a bit,” I said, speaking to Eve. “How come I’ve never seen you before?”

She gave me a hard, blank stare and then looked quickly away. “I don’t know,” she said.

Perhaps Barrow saw what I was going to do, for he suddenly finished his whisky and tapped Eve on her shoulder.

“You’d better go to bed,” he said in a domineering voice.

I thought if she has got what I think she has then she’ll tell him to go to hell; but she didn’t. “All right,” she said indifferently and rolled onto her knees.

“You mustn’t go yet,” I said. “Aren’t you two hungry? I have some stuff in the ice box that wants eating. What do you say?”

Barrow was watching Eve with uneasy, possessive eyes. “We had dinner at Glendora on our way up. She’d better go . . . she must be tired.”

I looked at him and laughed, but he wouldn’t play. He stared down at his empty glass, veins throbbing in his temples.

Eve stood up. She was even smaller and slighter than I had first supposed. Her head barely reached my shoulder.

“Where do I sleep?” she asked. Her eyes looked over my shoulder.

“Please keep the room you’re in now. I’ll use the guest room. But, if you don’t really want to go to bed, just yet, I’d be glad to have you stay.”

“I want to go.” She was half-way to the door.

When she had gone, I said, “I’ll see if she has everything,” and followed her out before Barrow could move.

She was standing by the electric heater, her hands behind her head. She stretched, yawned and when she saw me in the doorway, her mouth pursed and a calculating expression came into her eyes.

“Have you everything you need?” I asked, smiling at her. “Sure you won’t have something to eat?”

She laughed. I had a suspicion that she was mocking me and she knew why I was so concerned for her comfort. I hoped that she did know, because it would save time and dispense with the preliminary advances.

“I don’t want anything . . . thank you.”

“Well, if you’re sure, but I want you to feel at home. This is the first time I’ve had a woman in my cabin, so it’s kind of an occasion.” I knew I had made a mistake as soon as I had spoken.

The smile immediately went from her eyes and the cold quizzing look came back. “Oh?” she said, moving to the bed. She took a pink silk night dress out of her grip and tossed it carelessly into the chair.

She knew I was lying and the way her expression changed told me she expected me to be a liar anyway. This annoyed me. “Is that hard to believe?” I asked, stepping further into the room.

She bundled various garments scattered on the bed into her bag and then moved it onto the floor. “Is what hard to believe?” she asked, going to the dressing table.

“That I don’t have women here?”

“It’s nothing to me who you have here, is it?”

Of course she was right, but I was irritated by her indifference.

“Put like that,” I said, feeling snubbed, “I suppose it isn’t.”

She patted her hair absently and looked hard at herself in the mirror. I felt that she had forgotten that I was in the room.

“You’d better let me have your wet clothes,” I said. “I’ll put them in the kitchen to dry.”

“I can take care of them.” She turned abruptly away from the mirror and pulled her dressing gown more closely to her. The two furrows above the bridge of her nose were knitted in a frown. But, in spite of her plainness, and she looked very plain with that wooden look on her face, she intrigued me.

She glanced at the door and then at me. She did this twice before it dawned on me that she was silently telling me to go. It was a new experience for me and I did not like it.

“I want to go to bed . . . if you don’t mind,” she said and turned away from me.

No gratitude, no thanks, no question about taking my room, just a cool, deliberate brush-off.

Barrow was fixing himself a drink when I entered the sitting room. He lurched unsteadily as he made his way back to the armchair. He sat down and stared up at me, screwing up his eyes to see me more clearly. “Don’t get ideas about her,” he said, suddenly banging his fist down on the armchair. “You lay off. Do you understand?”

I stared at him. “Are you talking to me?” I said, outraged that he dared to take such an attitude.

His red face sagged a little. “You leave her alone,” he mumbled. “She’s mine for tonight. I know what you’re up to, but let me tell you something.” He edged forward and pointed a stumpy finger at me, his slack mouth working. “I’ve bought her. She cost me a hundred bucks. Do you hear? I’ve bought her! So keep off the grass.”

I didn’t believe him. “You couldn’t buy a woman like that. Not a down-at-heel punk like you.”

He slopped whisky over the carpet. “What was that?” He looked up at me with watery, mean eyes.

“I said you couldn’t buy a woman like that because you’re a down-at-heel punk.”

“You’ll be sorry for that,” he said. The two veins in his temple beat faster. “As soon as I saw you, I knew you’d start trouble. You’re going to try to take her from me, aren’t you?”

I grinned at him. “Why not? There’s nothing you can do about it, is there?”

“But I’ve bought her, damn you,” he exclaimed, punching the arm of the chair. “Don’t you know what that means? She’s mine for tonight. Can’t you act like a gentleman?”

I still didn’t believe him. “Let’s have her in,” I said, laughing at him. “After all, a hundred dollars isn’t a great deal of money. I might offer more.”

He struggled out of his chair. He was drunk, but there was a lot of weight in his shoulders. If he caught me when I wasn’t ready for him, he might do me some damage. I backed away.

“Now don’t get excited,” I said, giving ground as he crowded me. “We can settle this without fighting about it. Let’s get her in . . .”

“She’s had a hundred bucks from me,” he said, speaking in a low furious voice. “I’ve waited eight weeks for this. When I asked her to come away with me she said all right. But when I went to her place her goddam maid said she was out. Four times she pulled that trick on me and each time I knew she was upstairs laughing at me and watching me from her window. But I wanted her. I was a sucker, see? I raised the price every time I called. And she came when I said a hundred bucks. It was all right until you turned up. Neither you nor any other monkey will stop me now.”

He made me feel a little sick. I still only half believed him, but I was certain I could not have him in the cabin any longer. He had to go.

I took out my wallet and tossed a hundred dollar note at his feet. As an afterthought I added another ten. “Get out,” I said. “There’s your money with interest.”

He stared down at the money, blood leaving his face. He made a soft choking noise as if he were trying to clear the phlegm in his throat. Then he raised his face and I saw I had a fight on my hands. I did not want to fight him, but if he wanted it that way, he could have it.

He shuffled towards me, his long arms held forwards as if he were going to tackle me. When he was within reach, he made a grab at me. I did not avoid him, but stepped close and slammed my fist in his face and ripped down. The big signet ring I wore on my little finger ploughed a furrow in his cheek. He rocked back with a grunting gasp and I hit him again on the bridge of his nose. He went down heavily on his hands and knees. Then I walked over to him and deliberately taking aim, I kicked him under his chin. His head snapped back and he collapsed on the carpet. He was finished and he hadn’t even touched me.

Eve stood in the doorway watching. Her eyes were wide with surprise.

I smiled at her. “It’s all right,” I said, blowing on my knuckles. “Go back to bed. He’s leaving in a moment.”

“You didn’t have to kick him,” she said coldly.

“No.” I liked the flash of anger in her eyes. “I shouldn’t have done that. I guess I got mad. I wish you’d go away.”

She went then and I heard the bedroom door close.

Barrow sat up shakily and put his hand to his face. Blood ran down his fingers onto his cuff. He looked at it stupidly and then touched his throat.

I sat on the table and watched him. “You’ve got a two mile walk to Big Bear Lake. You can’t miss the road. Just keep straight on downhill. There’s a hotel before you reach the lake. They’ll put you up. Now, beat it.”

He did something I hadn’t expected from him. He put his hands to his face and wept. That told me he was yellow right through.

“Get up and beat it,” I said in disgust. “You make me sick.”

He got up and moved to the door. His arm was across his eyes and he was snivelling like a kid who’s hurt.

I picked up the hundred and ten dollar bills and shoved them into his top pocket.

He actually thanked me. He was as yellow as that.

I took him to the front door, gave him his bag that stood in the lobby and shoved him into the rain.

“I don’t like your kind,” I said, “so keep out of my way.”

I watched him move down the stoop, then the rain and the wind and the dark closed around him.

I shut and locked the door and stood in the lobby. I had a tight feeling in my chest and head and I badly wanted a drink. But there was one thing I had to know which wouldn’t wait for a drink. I went to my bedroom and pushed open the door.

Eve stood by the dressing table, her arms locked tightly across her breasts. Her eyes were watchful.

“He’s gone,” I said, remaining in the doorway. “I gave him the hundred dollars you owed him and he actually thanked me.”

There was no change in her expression, nor did she say any-thing. She had the stillness of a cornered, dangerous animal.

I eyed her. “Don’t you feel sorry for him?”

Her mouth tightened in contempt. “Why should I feel sorry for any man?”

When she said that I knew what she was. I didn’t have to kid myself any longer. I really hadn’t thought that Barrow was lying. The stuff about the maid and how he had bargained was too smooth to be a lie. I was hoping it was a lie, but now, I knew it wasn’t.

So she was anybody’s woman. No one would have known it to look at her. She had ignored me. She — a woman who was looked upon by society as an outcast — had had the audacity to ignore me. I suddenly wanted to hurt her as I never had wanted to hurt anyone before.

“He told me he’d bought you,” I said, moving into the room and closing the door. “You’re very deceptive, aren’t you? You know I really didn’t think you would be for sale. A hundred dollars, wasn’t it? Well, I’ve taken you over, only don’t think I am paying any more. I’m not, because I can’t imagine you could be worth more than a hundred dollars to me.”

She didn’t move nor did her wooden expression change. Her eyes were a shade darker and the sides of her nostrils had gone white. She leaned against the dressing table, one small white hand playing with a heavy brass ashtray that happened to be at her side.

I walked over to her. “It’s no use looking at me like that. I’m not afraid of you. Come on, show me what you can do.”

As I reached out for her, she suddenly whipped up the ashtray and smashed it down on my head.

CHAPTER FOUR

IT is true to say that most men lead two lives — a normal life and a secret life. Society is, of course, only able to judge a man’s character by his normal life. If he makes a mistake, however, and his secret life becomes public property, then he is judged by his own secret standards and is, more often than not, ostracized as a punishment. In spite of this, he is still the same man who, a moment before, received the plaudits of Society. At least, he is the same man with the one important difference: he has been found out.

By now, because of my complete frankness, you may have come to the conclusion that I am an exceedingly unpleasant person. You may even have decided that I am unethical, dishonest, vain and worthless. These conclusions are not due to your insight and perception, they are due entirely to my own frankness.

If you met me socially, if you became my friend, you would find me quite as agreeable as any one of your other friends because I should be most careful always to be at my best in your company.

I would not bother with such an elementary point as this if it were not for the fact that you may wonder why Carol loved me. Even now I remember her with deep attachment. She was a person of great sincerity and integrity. I would not like you to judge her by my standards because she loved me.

Carol knew only that part of my nature that I chose to reveal to her. Towards the end of our association, circumstances became so difficult to control that she did finally discover my faults. But up to that time, I hoodwinked her as successfully as some of you are hoodwinking those who love you.

It was because Carol was always understanding and sym-pathetic that, after staying two days at Three Point, following the night I first met Eve, I drove into Hollywood to see her.

The service station at San Bernardino had taken care of my car. They had told me that they had also taken care of the Packard. As I drove down the hill road from Big Bear Lake, I came upon a gang of men working on the obstruction in the road. They had nearly cleared it, but I had some difficulty in passing. The foreman of the gang knew me and he had planks laid across the soft ground and a bunch of men practically carried the car over.

I reached Carol’s apartment off Sunset Strip about seven o’clock. Frances, her maid, told me she had only just returned from the Studios and was changing.

“But come right in, Mr. Thurston,” she said, beaming at me. “She won’t be but a few minutes.”

I followed her ample form into Carol’s living room. It was a nice room, modern and quiet and the concealed lighting was restful. I wandered around while Frances fixed me a highball. She always made a fuss over me and Carol had once laughingly told me that Frances considered me her most distinguished visitor.

I sat down and admired the room. It was simply furnished. The chair and large settee were of grey suede and the hangings were wine coloured.

“Every time I come into this room,” I said, taking the highball Frances offered me, “I like it better. I must ask Miss Rae to get me out some designs for my place.”

Carol came in while I was speaking. She was wearing a foamy negligée, caught in at her waist by a broad red sash, and her hair was dressed loosely to her shoulders.

I thought she looked pretty good. She wasn’t a beauty — at least, she wasn’t stamped from the Hollywood mould. She reminded me, as she came in, of Hepburn. She was the same build, nicely put together with the right things in the right places. Her complexion was pale which offset her scarlet lips and her skin seemed to have been pulled too tightly across her face, revealing the bone structure. Her eyes, her best feature, were big, intelligent and alive.

“Why, hello, Clive,” she said gaily, coming swiftly across the room. She held a cigarette in an eighteen-inch holder. The long holder was her only mannerism. It was a clever one because it showed off her beautiful hands and wrists. “Where have you been these last three days?” Then she paused and looked questioning at my bruised forehead. “What have you been doing?”

I took her hands. “Fighting a wild woman,” I said, smiling down at her.

“I might have guessed that,” she said, glancing at my knuckles, still skinned from the punch I’d given Barrow. “She must have been a very wild woman.”

“Oh, she was,” I said, leading her to the settee. “The wildest woman in California. I’ve come all the way from Three Point to tell you about her.”

Carol settled herself in the corner of the settee and drew her legs up under her.

“I think I’ll have a highball,” she said to Frances. A little of her gaiety had gone from her eyes. “I have a feeling Mr. Thurston’s going to shock me.”

“Nonsense,” I said. “I hope to interest you, but that’s all. I’m the one who’s shocked.” I sat down by her side and took her hand. “Have you been working very hard today? There are smudges under your eyes. They suit you, of course, but do they mean tears and toil or are you, at last, becoming dissolute?”

Carol sighed. “I’ve been working. I have no time to be dissolute and I’m sure I’d be very bad at it. I am never any good at anything that doesn’t interest me.” She took the highball from Frances and smiled her thanks.

Frances went away.

“Now,” she went on, “tell me about your wild woman. Are you in love with her?”

I looked at her sharply. “Why do you think I must fall in love with every woman I met? I’m in love with you.”

“So you are.” She patted my hand. “I must remember that. Only, after three days without seeing you, I was wondering if you had dropped me. So you’re not in love with her?”

“Don’t be tiresome Carol,” I said, not liking her mood. “I’m most certainly not in love with her,” and settling back against the cushions I told her about the storm, Barrow and Eve. But, I didn’t give her all the details.

“Well, go on,” she said as I paused to finger the bruise on my forehead. “After she had laid you out, what did she do? Pour water over you or skip with your wallet?”

“She skipped without my wallet. She didn’t take a thing . . . she wasn’t the type. Don’t get this woman wrong, Carol, she isn’t the usual kind of hustler.”

“They seldom are,” Carol murmured smiling at me.

I ignored that. “While I was unconscious, she must have dressed, packed her grip and gone off into the storm. That was quite a thing to do . . . it was blowing and raining like hell.”

Carol studied my face. “After all, Clive, even a hustler has her pride. You were rather beastly to her. In a way, I admired her for knocking you on your conceited head. Who was the man, do you suppose?”

“Barrow? I have no idea. He looked like a travelling salesman. Just the kind of jerk who’d pay a woman to go out with him.”

I hadn’t told Carol about giving Barrow the hundred and ten dollars. I didn’t think she’d understand that part of the story.

“I suppose you didn’t want to get rid of him so you could have a heart to heart chat with the lady?”

I felt suddenly irritated that she should have touched truth so quickly. “Really, Carol,” I said sharply, “a woman of that type doesn’t appeal to me. Aren’t you being a little ridiculous?”

“Sorry,” she said, wandering over to the window. There was a pause, then she went on, “Peter Tennett said he’d be over. Will you have supper with us?”

“I now regretted telling her about Eve. “Not tonight,” I said, “I’m tied up. Is he calling for you?”

I wasn’t tied up, but I had an idea at the back of my mind and I wanted the evening to myself.

“Yes, but you know Peter . . . he’s always late.”

I knew Peter Tennett all right. He was the only one of Carol’s friends who gave me an inferiority complex. But I liked him. He was a grand guy. We got along fine together, but he had too many genuine talents for me. He was producer, director, script writer, and technical adviser all rolled into one. Everything he undertook had, so far, been successful. He had the magic touch and he ranked as number one at the Studios. I hated to think what he made in a year.

“Can’t you really come?” Carol asked, a little wistfully. “You ought to see more of Peter. He might do something for you.”

Lately, Carol had been continually suggesting various people who might put something in my way. It irritated me that she should think I needed help.

“Do something for me?” I repeated, forcing a laugh. “What on earth could he do for me? Why, Carol, I’m getting along fine . . . I don’t need any help.”

“Sorry again,” Carol said, not turning from the window. “I seem to be saying all the wrong things tonight, don’t I?”

“It isn’t you at all,” I said, going over to her. “I’ve still got a headache and I’m edgy.”

She turned. “What are you doing, Clive?”

“Doing? Well, I’m going out to dinner. My — my publishers . . .”

“I don’t mean that. What are you working at? You’ve been at Three Point for two months now. What’s happening?”

This was the one subject I wanted to avoid with Carol. “Oh, a novel,” I said carelessly. “I’m just laying out the blueprint. I start working seriously next week. Don’t look so worried,” and I tried to smile at her assuringly.

Carol was an extraordinarily difficult person to lie to. “I’m glad about the novel,” she said, shadows in her eyes, “but I wish it were a play. There’s not much in a novel, is there, Clive?”

I raised my eyebrows, “I don’t know . . . film rights . . . serial rights . . . maybe Collier’s will take it. They paid Imgram fifty thousand dollars for his serial rights.”

“Imgram wrote an awfully good book.”

“And I’m going to write an awfully good book too,” I said. Even to me, it sounded a little lame. “I’ll write another play in a little while, but I’ve got this idea for a book and I don’t want it to grow cold on me.”

I had an uneasy feeling that she was going to ask me what the book was about. If she’d done that, I would have been in a spot, but at that moment Peter came in and for once I was glad of the interruption.

Peter was one of the few successful Englishmen in Hollywood. He still had all his clothes made in London and the Sackville Street cut was right for his English type of figure, broad in the shoulders and slimming down at the hips.

His dark, thoughtful face lit up when he saw Carol. “Not dressed yet?” he said, taking her hand. “But looking very lovely. Sure you’re not too tired to come out tonight?”

“Of course not,” Carol said smiling.

He looked over at me. “How are you, my dear boy?” He shook hands. “Doesn’t she look wonderful?”

I said she certainly did and noticed his eyes were question marks when he saw my bruise.

“Give him a drink, Clive, while I dress,” Carol said. “I won’t be long.” She looked over at Peter. “He’s being stuffy . . . he won’t dine with us.”

“Oh, but you must . . . this is an occasion, isn’t it, Carol?”

Carol shook her head helplessly. “He’s dining with his publishers. I don’t believe it, but I suppose I’d better be tactful and pretend I do. Look at that bruise . . . he’s been fighting a wild woman.” She laughed, turning to me, “Tell him, Clive . . . he may think it’s a story.”

Peter beat me to the door. He opened it. “Don’t hurry,” he said. “I’m feeling very leisurely tonight.”

“But I’m hungry,” Carol protested. “Don’t let’s be too late,” and she ran from the room.

Peter came over to the little bar in the far corner of the room where I was fixing myself another drink. “So you’ve been fighting, have you?” he said. “That’s quite a nasty bruise you have there.”

“Never mind about that,” I said. “What will you drink?”

“A little whisky, I suppose.” He leaned against the bar and selected a cigarette from a heavy gold case. “Carol’s told you the news?”

I gave him bourbon and water. “No . . . what news?”

Peter raised his eyebrows.” Funny kid . . . now I wonder why . . .” He lit his cigarette.

I had a sudden sinking feeling. “What news?” I repeated, staring at him.

“She has been given the script of the year. It was arranged this morning . . . Imgram’s novel.”

I slopped whisky on the polished bar. Hearing him say that was wormwood to me. Of course, I knew I couldn’t have handled Ingram’s theme. It was too big for me, but it came as a blow to hear that a kid like Carol was to do it.

“Why, that’s terrific,” I said, trying to look pleased. “I’ve been reading it in Collier’s. It’s a great story. You producing?”

He nodded. “Yes, there are all sorts of angles. It’s just the kind of story I’ve been looking for. Of course, I wanted Carol to do the script, but I didn’t think Gold would agree. Then, while I was working out how best to persuade him, he actually called me in to say she’s to do it.”

I came around from behind the bar and carried my drink to the settee. I was glad to sit down. “What will it mean?”

Peter shrugged. “Well, a contract, of course . . . bigger money . . . screen credit . . . and another chance if she makes good.” He tasted his whisky. “And she will, of course. She is very talented.”

I was beginning to think that everyone in this game had talent except myself.

He came over and dropped into an armchair. He seemed to sense that the news had shaken me. “What are you working on now?”

I was getting tired of this interest in my work. “A novel,” I said shortly. “Nothing of interest to you.”

“That’s a pity. I’d like to film something of yours.” He stretched out his long legs. “I’ve been meaning to talk to you before. Ever thought of working for Gold? I could give you an introduction.”

I wondered suspiciously if Carol had been getting at him.

“What’s the use, Peter? You know me. I can’t work for anyone. From what Carol tells me working at your Studio is refined hell.”

“It’s also big money,” Peter said, taking the drink I handed to him. “Think it over and don’t leave it too long. The public has a short memory and Hollywood an even shorter one.” He didn’t look at me, but I had a feeling that there was more to it than just casual conversation. It was almost a warning.

I lit a cigarette and brooded. There is one thing you don’t tell other writers or producers in Hollywood. You don’t tell them that you are out of ideas. They find that out quick enough for themselves.

I knew that if I went back to Three Point the same thing would happen as had happened these past two days. I’d think about Eve. I hadn’t stopped thinking about her since I found myself lying on the floor in the deserted cabin with the sun coming through the curtains. I had tried to wash her out of my mind, but I couldn’t do it. She was there in my bedroom, she was sitting with me on the porch, she was staring at me from the blank sheet of paper in my typewriter.

It finally got so bad that I had to talk to someone about her. That was why I had come into Hollywood to see Carol. But when I began to talk, I found I couldn’t tell her the things that were really on my mind. I couldn’t tell Peter either. I couldn’t tell them how I was feeling about Eve. They would have thought I was crazy.

Maybe I was crazy. I had the pick of some twenty smart, attractive women. I had Carol who loved me and who meant a lot to me. But that didn’t seem enough for me. I had to become infatuated with a prostitute.

Perhaps, infatuated wasn’t the right word. I had sat on the porch, the previous night, with a bottle of Scotch at my elbow and I had tried to reason it out. Eve had hurt my pride. Her cold indifference had been a challenge to me. I felt she was living in a stone fortress and I had to storm that fortress and break down its walls.

I was pretty drunk by the time I’d come to these conclusions, but I’d made up my mind I was going to conquer her. All the women I’d played around with in the past had been too easy. I wanted a proposition that I could really get my teeth into. Eve would give me a run. She’d be difficult and the idea excited me. It would be a contest with no holds barred. She wasn’t an innocent little thing who could be twisted around my finger without any effort. She had unconsciously thrown down the challenge and I was going to take it up. I had no doubts what the final results would be. Nor did I think of what would happen once I’d taken her by storm. That could take care of itself when the time came.

I snapped out of my thoughts as Carol came in. She had changed into an ice-blue evening dress over which she wore a short ermine coat.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I said, jumping to my feet. “I’m terribly glad and proud of you, Carol.”

She looked at me searching. “It is exciting, isn’t it, Clive? Won’t you come now . . . we ought to celebrate.”

I wanted to, but I had something more important to do. If we’d been alone, I’d have gone with her, but with Peter, it wasn’t quite the same thing.

“I’ll join you later if I can,” I said. “Where are you eating?”

“The Vine Street Brown Derby,” Peter said. “How long will you be?”

“It depends,” I said. “Anyway, if I don’t turn up, I’ll meet you both here after dinner . . . all right?”

Carol put her hand in mind. “It’ll have to be,” she said. “You will try, won’t you?”

Peter got up. “Well, then, let’s go. Are you coming our way?”

“I promised to meet my publisher at eight,” I explained. It was only half past seven. “Do you mind if I stay here for a few minutes? I’d like to finish my drink and I have some calls to make.”

“No . . . come on, Peter, we mustn’t interfere with business.” Carol waved to me. “Then we’ll see you? Are you going back to Three Point tonight?”

“I think so, otherwise, if I’m very late, I’ll go over to the penthouse, but, I want to start work tomorrow.”

When they had gone, I poured myself out another whisky and picked up the telephone book. There were a number of Marlows in the book. Then with a sudden feeling of excitement I saw her name. The address was a house on Laurel Canyon Drive. I had no idea where that was.

For several seconds, I hesitated, then I picked up the tele-phone and dialled her number. I listened to the steady burr- burr of the bell, then there was a click and my blood began to move around in me, like a prospective tenant looking over a house.

A woman, it wasn’t Eve, said, “Hello?”

“Miss Marlow?”

“Who is calling?” The voice was cautious.

I grinned into the telephone. “She won’t know my name.”

There was a pause, then the woman said, “Miss Marlow wants to know what you want.”

“Tell Miss Marlow to come off her high horse,” I said. “I’ve been advised to call her.”

There was another pause, then Eve came on the line. “Hello,” she said.

“Can I come and see you?” I kept my voice low so she wouldn’t recognize it.

“You mean now?”

“In half an hour.”

“I suppose so.” She sounded doubtful. “Do I know you?”

I thought this was a hell of a conversation. “You will before long,” I said and laughed.

She laughed too. Her laugh sounded good on the telephone. “Then you’d better come along,” she said and hung up.

It was as simple and as easy as that.

CHAPTER FIVE

LAUREL CANYON DRIVE was a narrow street with a scattering of small-town style frame dwellings, partly hidden by hedges and shrubs.

I drove slowly down the street until I saw the number of Eve’s house painted on a small white gate I stopped and got out.

There was no one in sight and the house itself was discreet. Once I was through the gate, the high hedge hid me from the street. I walked down the path that went steeply to the front door which, in its turn, was screened by a built-in porch. The windows on each side of the door were curtained with cream muslin. I had to walk down several wooden steps before I was level with the front door.

The knocker on the door was an iron ring which passed through the body of a naked woman. It was a nice design and I studied it for a few seconds before I knocked. I waited, aware that my heart was thumping with suppressed excitement.

Almost immediately I heard an electric light switch click on and then the door opened. A tall, angular woman, almost as tall as myself, stood squarely in the doorway.

The light in the passage floodlit me while she remained in the shadows. I could feel her eyes crawling over me, then as if satisfied by what she saw, she stood aside.

“Good evening, sir. Have you an appointment?”

As I stepped round her into the lobby, I looked curiously at her. She was a red-faced woman of about forty-five or so. Her face was sharp with a pointed chin, pointed nose and small bright eyes. Her smile had just the right blend of friendly servility.

“Good evening,” I said. “Miss Marlow in?”

I felt acute embarrassment and irritation. It was hateful to me that this woman should see me and should know why I had come to this sordid little house.

“Will you come this way, sir?” She moved down the passage and opened a door.

My mouth was dry and I felt a pulse beating in my temples as I entered the room.

It was not a large room. Facing me was a dressing table fitted with a bevelled mirror; on the floor in front of the dressing table, was a thick white rug. To the left of the rug was a small chest of drawers on which stood several tiny glass animals. On the far right was a cheap, white-painted wardrobe. A large divan bed, covered by a shell-pink bedspread took up the remaining space.

. Eve stood by the empty fireplace. Near her was a small armchair and a bedside table on which stood a reading lamp and several books.

She was wearing the same short-sleeved blue dressing gown and her face was wooden under careful make-up.

We looked at each other.

“Hello,” I said, smiling at her.

“Hello.” Her expression did not change nor did she move. It was a suspicious, indifferent greeting.

I stood looking at her, slightly embarrassed, puzzled that she showed no surprise at seeing me again and irritated about the dressing gown. But in spite of the hostile atmosphere, my blood moved fast through my veins.

“So we meet again,” I said a little lamely. “Aren’t you surprised to see me?”

She shook her head. “No . . . I recognized your voice.”

“I bet you didn’t,” I said. “You’re kidding.”

Her mouth pursed. “I did . . . besides, I was expecting you.”

I must have shown my startled surprise because she suddenly laughed. The tension eased immediately.

“You were expecting me?” I repeated. “Why?”

She looked away. “Never mind.”

“But I do mind,” I insisted, walking round her and sitting in the armchair. I took out my cigarette case and offered it.

Her eyebrows went up, but she took a cigarette. “Thank you,” she said. She hesitated, and then sat down on the bed near me.

I also took a cigarette, thumped my lighter and as she leaned forward to light up, I said, “Tell me why you were expecting me.”

She shook her head. “I’m not going to.” She let smoke drift down her nostrils and she glanced uneasily round the room. She was on the defensive and I felt instinctively that she was nervous and unsure of herself.

I studied her for a few seconds. As soon as she felt my eyes on her face, she turned to look directly at me. “Well?” she said sharply.

“It’s a pity you make-up like that. It doesn’t suit you.”

She stood up immediately and looked into the mirror over the fireplace. “Why,” she asked, staring hard at herself. “Don’t I look all right?”

“Of course, but you’d look better without all that muck on your face. You don’t need it.”

She continued to look at herself in the mirror. “I’d look an awful fright without it,” she said, half to herself, then she turned and frowned at me.

“Did anyone tell you you’re an interesting woman?” I asked, before she could speak. “You have character and that’s more than most women have.”

Her mouth tightened and she sat down. For a moment I had caught her off guard, but the wooden expression was now back again.

“You haven’t come here to tell me I’m interesting, have you?”

I smiled at her. “Why not? If no one has told you before, then it’s time someone did. I like to give women their due.”

She flicked ash into the fireplace. It was a nervous, irritable movement and I could see she did not know what to make of me. As long as I could keep her in that frame of mind I held the initiative.

“Aren’t you going to say sorry for this?” I asked, touching the bruise on my forehead.

She said what I expected her to say. “Why should I? You deserved it.”

“I suppose I did,” I said and laughed. “I’ll have to be careful next time. I like a woman with spirit. I’m sorry about the way I behaved, but I did want to see what your reactions would be.” I laughed again. “I didn’t expect to feel your reactions.”

She looked at me doubtfully, smiled and then said, “I do get wild sometimes . . . but you deserved it.”

“Do you always treat men like that?”

She hedged. “Like what?”

“Knocking them on the head if they annoy you,”

This time she giggled. “Sometimes.”

“No hard feelings?”

“No.”

I watched her. She slouched as she sat, her head forward and her slim shoulders rounded. Again she looked sharply at me when she felt my eyes on her.

“Don’t sit there looking at me,” she said irritably. “Why did you come here?”

“I like looking at you,” I returned, relaxing in the armchair and feeling completely at ease. “Can’t I talk to you? Would that strike you as odd?”

She frowned. I could see she was in two minds. She did not know whether I was wasting her time or whether I was here professionally. It was obvious that she was controlling her im-patience with difficulty.

“You have only come here to talk?” she said, looking at me and then immediately looking away. “Isn’t that a waste of time?”

“I don’t think so. You interest me and besides I like talking to attractive women.”

She looked up at the ceiling with an exaggerated expression of exasperation. “Oh they all say that,” she said impatiently.

That annoyed me. “If you don’t mind I would rather not be classed with an anonymous “they”,” I said with acerbity.

She looked surprised. “You have a very good opinion of yourself, haven’t you?”

“Why not?” It was my turn to be impatient. “After all, who’ll believe in me if I don’t?”

Her face darkened. “I don’t like conceited men.”

“Haven’t you a good opinion of yourself?”

She shook her head emphatically. “Why should I?”

“I hope you’re not just another woman with an inferiority complex?”

“Do you know so many?”

“Quite a few. Is that what you suffer from?”

She stared into the empty fireplace, her expression suddenly moody. “I suppose so.” Then she looked up suspiciously. “Do you think that’s funny?”

“Why should I? I think it’s rather pathetic because there’s no reason for you to.”

She raised her eyebrows questioningly. “Why not?”

I knew then that she was unsure of herself and interested to know what I thought of her.

“You ought to be able to answer that if you are truthful about yourself. Now my first impressions of you . . . no, never mind, I don’t think I’ll tell you.”

“Come on,” she said, “I want to know. What are your first impressions of me?”

I studied her as if I were making a careful assessment of her qualities. She stared back at me, frowning and ill at ease, but wanting to know. I had thought so much about her for the past two days that I was long past first impressions. “If you really want to know,” I began with assumed reluctance, “only I don’t suppose you’ll believe me.”

“Oh, come on,” she said impatiently, “don’t hedge.”

“All right. I’d say you are a woman of considerable character, independent to a degree, hot tempered and strong willed, extra-ordinarily attractive to men and, oddly enough, sensitive in your feelings.”

She studied me doubtfully. “I wonder how many women you have said that to?” she asked, but I could see she was secretly pleased.

“Not many . . . none at all if you take it as a whole. I haven’t met any one woman with all those qualities except yourself. But, of course, I really don’t know you yet, do I? I may be entirely wrong . . . they’re just first impressions.”

“Do you find me attractive?” She was in deadly earnest now.

“I would hardly be here if I didn’t. Of course you’re attractive.”

“But why? I’m not pretty.” She got up and looked in the mirror again. “I think I look awful.”

“Oh no, you don’t. You have character and personality. That’s much better than insipid prettiness. There’s something extraordinary about you. Magnetic is perhaps, the word.”

She folded her arms across her small, flat breasts. “I think you’re an awful liar,” she said, anger in her eyes. “You don’t really think I believe all this slop, do you? What exactly do you want? No one else comes here smarming over me like this.”

I laughed at her. “Don’t get angry. You know, I’m sorry for you. You certainly have a bad inferiority complex. Never mind, perhaps one day you’ll believe me.” I leaned forward to examine the books on the beside table. There were copies of Front Page Detective, a shabby copy of Hemingway’s To Have and to Heme Not, and Thorne Smith’s Night Life of the Gods. I thought they were an odd assortment.

“Do you read much?” I asked deliberately changing the subject.

“When I can find a good book,” she returned, bewildered.

“Have you ever read “Angels in Sables”?” I asked, naming my first book.

She moved restlessly to the dressing table. “Yes . . . I didn’t like it much.” She picked up a powder puff and dabbed at her chin.

“Didn’t you?” I was disappointed. “I wish you’d tell me why.”

She shrugged. “Oh, I just didn’t.”

She put down the powder puff, stared at herself in the mirror and then moved back to the fireplace. She was fidgety, impatient and a little bored.

“But you must have reasons. Did you find it dull?”

“I don’t remember. I read so quickly I never remember any-thing I read.”

“I see . . . anyway you didn’t like it.” I was irritated that she couldn’t remember my book. I would have liked to have talked to her about it and had her reactions, even if she did not like it I began to realize that normal conversation with her was going to be difficult. Until we knew each other — and I was determined that we should know each other — topics of conversation were severely limited. Up to now, we had nothing in common.

She stood looking at me doubtfully and then sat down on the bed again. “Well?” she said, abruptly. “What now?”

“Tell me something about yourself.”

She shrugged and made a little grimace. “There’s nothing to tell.”

“Of course there is,” I said and leaning forward, I took her hand in mine. “Are you married or is this a phoney?” I was twisting the thin gold wedding ring on her finger.

“I’m married.”

I was a little surprised. “Is he nice?”

She looked away. “Mmm-hmm.”

“Very nice?”

She took her hand away. “Yes . . . very nice.”

“And where is he?”

Her head jerked round. “That’s not your business.”

I laughed at her. “All right, don’t get high hat. I must say when you get mad, you look quite impressive. How did you get those two lines above your nose?”

She was up instantly, looking at herself in the mirror. “They’re bad, aren’t they?” she said, trying to smooth the furrows away with her finger tips.

I glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. I had been in the room exactly a quarter of an hour.

“Then you shouldn’t frown so much,” I said, getting to my feet. “Why don’t you relax?”