In just a few short weeks, a group of young orphans have come together to form a family. They have united in the most unlikely of alliances, finding strength in the tight bonds of friendship.

In their individual cultures, these orphans were seen as children. At best, they were ignored by their elders. At worse, they are treated as nuisances, told what they could and could not do.

But no one ever told them they couldn’t save the universe. Nobody knew they would ever get the chance…

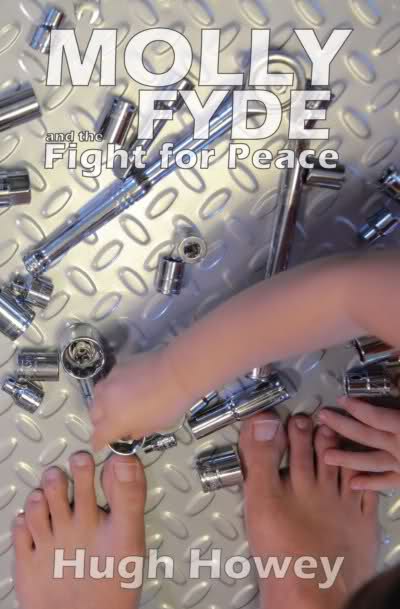

MOLLY FYDE AND THE FIGHT FOR PEACE

The Bern Saga: Book 4

by Hugh Howey

A Poem of Madness

Five links stand out in the chain that binds our will.

There’s the primal urges, wound tight in nucleotidal strands.

There’s the faith that surges through our clasped and superstitious hands.

There’s the politics of kings and queens, and their many rules.

There’s culture which forms mobs of motley fools.

Last comes our decisions, stacked

up in piles of regret

that we long

to forget.

These five links stand out in the chain that binds our will.

They hold us, guide us, coerce us—

And we rattle them still.

The Rape of the Canyon Queen

0

The cave hollows thundered with the Wadi’s coming. The great pads of her feet shuddered the rock as claws the size of a lesser Wadi’s tail met the walls of her cave with the crack of shattered stone. When the Canyon Queen moved, the world knew. For in her old age, the great Wadi had done more than forget how to scamper soft and slow—she had outgrown the need.

She came to a stop before one of the great watering shafts, the circumference of the black well wider than the span of her old birth canyon. The Canyon Queen bent her thick neck and drank from the condensation rushing out of side holes and gurgling down the deep shaft. She drank her fill, leapt across the gaping void, and continued her loud passage through the rock. As she bounded forward, her scent tongue picked up the vaporous trails of fear and haste from those scattering before her. None had ever grown to the Canyon Queen’s size, not that any alive could remember. And nobody knew what to do about it but stay out of her way.

The massive Wadi took the last turn in her vast warren, and the round maw of light at its termination came into view. She loped toward it, reaching out with powerful limbs, gripping marble with her claws, pulling herself along in an ecstatic release of energy. She ran with the dizzying might of a thing unopposed and for the pure thrill of it.

At the end of the shaft, she paused to read the air beyond. The wind outside was, as always, a turbulent mess. Her home was situated on the brightest point of them all, where the two great lights stood directly overhead and rarely cast a shadow. It was a very long way from where the Canyon Queen was born—way around where the canyons squeezed tight, where the Wadi holes dwindled to the size of her claw, and where the winds blew strong and steady in the same direction.

Far enough around that way, just past her birth canyon, and a Wadi could escape the light altogether, reaching a flat land of complete shade. The Canyon Queen knew. She knew a Wadi could scamper out into a world of solid cave-dark, spoiled only by the shimmering glimmer caused by the two lights over the horizon. She knew such a place existed, where there were no canyons and no watering shafts and Wadi would freeze if they stayed too long. She knew of such a place, but now lived as far from there as possible. So far—so very far into the light—that she frequently struggled to remember how she had arrived.

The great Wadi tasted the swirling, raucous air outside her warren and tried to sink claws into that long-ago past, remembering.

••••

Where have you been?

The young Wadi flew in agitated circles around the small cave. Dust drifted from the roof, caught in the light from the tunnel’s entrance like a veil of worry. She exuded the same mixture of scents over and over: Where have you been? Wherehaveyoubeen?

Her mate-pair staggered into the cave to join her, his body finally catching up to the scent of his arrival. He rubbed against her, scales scratching scales, but the young Wadi pulled back, leaving room for an answer. Where have you been? Wherehaveyoubeen?

Her mate-pair had been missing for three sleeps, his scents trailing off to a sad nothing. Now he was back, but his smells were agitated and impossible to read. Wherehaveyoubeen?

Water.

That single concept pierced the noisy smells, making itself clear in the young Wadi’s mind. She danced back and followed the cave’s turns to their shaft of meager drippings, leading the way. She tasted her mate-pair following close behind. Her brain reeled with the days of sadness mixed with the new joy of his return, all of it jumbled with the confusion of why he’d left and where he’d been. She reached their craggy hole of condensation and rushed to the far side. Her mate-pair leapt eagerly to the drippings. He drank and exuded his story:

Dark, he scented. Dark and cold. A walk so far, the two lights burrow into the rock itself and the land erupts with color.

Her mate-pair seemed to have lost his mind. The young Wadi licked the air, making sure she tasted it properly, wondering if perhaps he had spent three days chin-up to the two lights, roasting his brain.

Where did you go? She couldn’t stop exuding it.

Her mate-pair continued to drink what little water was there. The young Wadi looked over her shoulder, wondering if they would have to break a truce and fight for a bigger stream—

The blue hunters.

The image of large beasts on two legs flashed through her mind, scattering the rest.

The blue hunters came while you slept, a long file of them wrapped in their single silver scale covering all but their faces.

The young Wadi silenced her own worries and latched on to the stream of smells. She bent her head close to her mate-pair’s and breathed in every molecule lest some drift off to waste.

They took eggs from the shafts across the canyon. I followed even bigger hunters deeper while you slept. They took one of the mate-pairs we fought with last season—

Took?

The Wadi couldn’t help the interruption. Her body felt full to bursting with a thousand smells to release. Her mate-pair stopped his futile licking on the now-dry rock. He gazed at her, the blacks of his eyes wide in order to see in the dark. Or wider than even that, she saw. They were wide with fear.

They came with silver claws as long as their bodies, claws that could reach in warrens and pull out Wadi and their eggs. I watched them from an abandoned shaft as they crept along in the shadows. One blue hunter came and looked in after me. I could see his long claw, but it was no longer shiny. Wadi blood covered it, and a body hung there, pierced through its belly.

The young Wadi bobbed her head, trying to make sense of the images. Smells of the blue hunters had drifted through the canyons before, and some of the older Wadi—those who came back to lay their eggs—would leak such thoughts at times, but they were always like ghost memories, nothing vibrant and real and immediate as this.

What did you do?

I ran. I went deep in the caves, treading all over rock scented as someone else’s. I didn’t care. For all I knew, that someone else was gone, their body hanging on a claw. I ran until my brain cleared and I remembered you.

I was still sleeping?

It happened so fast. I came back through the fought-for interior, but no one was fighting. All were running. All were agitated. I ran past watering holes like we’d dreamed of, past eggs left abandoned, past Wadi twice my size and just as full of fear. I picked up your sleeping scent and came back to warn you. I was just around the bend when I heard the claw call.

Claw call? The young Wadi weaved her head around the scent, trying to make sense of its newness.

An urge to defend. To fight as one. I didn’t know it either, but it seized me. It was one of the elder females, one of the dwindling come back to lay her eggs.

She wasn’t dead yet?

Her mate-pair tapped his claws on the rock. Close, he scented. Very close. She had just laid her eggs and was feeding them. She told us. She commanded us to save them. My head was full of pictures of small blue hunters clutching her unborn babies. Her rage became mine, her scents my inner thoughts. I had no defenses—

A flood of sorry drowned out what her mate-pair was saying. He exuded a week’s supply of begging forgiveness, of shame and self-pity. It hung like a black fog in the tunnel, obscuring all else. The young Wadi scampered up the wall and around the watering hole; she nestled against her mate-pair, oozing all the acceptance and soothing she could. Her bright cloud of scent soon dispelled his darker other, and she remembered why this was her mate-pair. He and no other.

I had no defenses, he oozed again. I joined with the bigger Wadi and we gave chase. We followed the blue hunters into the winds and away from the twin lights. There were attacks, which brought bigger hunters with claws that shot lightning a million paces and with such precision—

Images of charred Wadi, of twitching limbs, of fighting and the dead—they flitted through the young Wadi’s mind. She saw elder blue hunters coming to the rescue of the younger ones. She saw that this was some sick ritual, something they did often and in different places. This new danger danced in her vision, scaring her and mocking her at once.

My cowardliness saved me, her mate-pair scented.

The thought wafted away during a lull in the smells.

My cowardliness saved me. It had more might than the rage driving me along, the rage from this old female and her stolen eggs. Or maybe the two had the same might, because I couldn’t return to you either. I was left following the eggs, wanting to retrieve them, but not knowing how. I had dreams of bringing them back and hatching them as my own. As if they were yours—

The young Wadi nestled closer to her mate-pair. We’ll have eggs enough, she wanted to scent him, but didn’t.

I followed them until the two lights sank beneath the rock and all became one great shadow. I followed them until the borrowed rage of the claw call melted from my bones and I felt, at last, how impossibly weary they were. I collapsed. I watched the blue hunters shrink across the black flatness, merging with so many other hunters in a bright, shiny warren that sat high on the ground. I laid on the cold rock and smelled nothing but death carried on the winds between me and these hunters. Death and alien excitement, our misery laced with their hope. It was awful. It was—

She pressed her scales close to her mate-pair and exuded calm and peace. The horror of his ordeal was so clear in her mind. Of all the terrible dreams of where her mate-pair had been for the last three sleeps, none compared to this.

I went in and out of sleeps so often, I lost track of time. My dreams were punctuated by alien scents, my mind filled with their jubilation and celebrations. The scents dissipated for some time, then new ones returned. Images of more blue hunters filled me, tormenting me as I lay dying. I wanted them to come and take me, to put an end to it, but then I kept thinking of you, back here and all alone.

The young Wadi tensed; she looked through the darkness and searched for some sign of the hunters, of their coming. Her mate-pair picked up on the thoughts.

No, he scented her, I staggered back to our canyon, their smells and the wind pushing me along, but they were not to follow. There are far more canyons than you can dream of. These new hunters chose to go down another—

But for how long? she wanted to know. How long before they return?

Many sleeps, I hope.

We need to move away from this black place, she scented him.

When we’re bigger, we will.

The Wadi slapped at the dry watering hole, her claws clicking with a hollow, fragile sound. Grow bigger on this?

She hated herself for scenting it. She hated the still air it brought between them. She scratched her mate-pair’s scales and added to his fog of sorry.

He nuzzled her back, then scented: When we’re bigger, the eggs will come.

What? What did he mean?

The female who lost her eggs, the dwindling elder, our minds became as one when her rage flooded inside me. I saw the story of her eggs—she showed us why they were worth saving. She had journeyed deep along the winds many thousands of sleeps ago, growing bigger as the caves grew. There were visions of her mate-pair, of her with eggs in her belly, of her body shrinking as she fed them, of a dangerous journey back to the cool hatching rocks where we were born, of her mate-pair dead from defending her—

Dead? The young Wadi nuzzled closer, her brain reeling from the shared experiences flashing through her mind.

Dead, but ready to live on in those eggs, to pass along all her scents and memories. Oh, but if not for my cowardice—

I’m glad of it, the young Wadi scented. I don’t want you dead.

It’s the way of the eggs, he scented her.

Then it’s good we aren’t having any.

We’ll have them when we get bigger. Twice or triple our size now, and we’ll be having them and fighting our way back here for the hatching.

Then we won’t get bigger, the young Wadi said.

But if the hunters come again—?

She rubbed her scales against his, could feel his trembling weakness still skittering through his bones, his heart racing and light from his ordeal.

We’ll claw through that canyon when we get to it, she scented. For now, relax. Relax, and then we’ll move from this darkness and claim us a better watering shaft.

00

Better shafts quickly became bigger shafts, and the two Wadi grew right along with them. It had been difficult to spot the changes at the time, since everything had enlarged together. Neighboring Wadi, their own claws, each other, the sizes of their ever-changing warrens, everything had grown as they made their way along the winds.

Suddenly, the Canyon Queen could remember it well. Her scent tongue probed the recesses of her mouth and tasted the myriad molecules lodged there over thousands of sleeps of forgetting. She looked down at her massive claws, each of them as big now as her entire body had been when she’d lost him. She pressed one of her claws into the solid rock and watched the marble crack and splinter under the pressure. She had a sudden impulse to smash the weakened marble with her balled hand, breaking stone, or self, or both. She gripped the tunnel’s edge instead and tasted the winds of the past for more memories.

She wasn’t sure why she needed to dwell on it. Why now, with the tunnels not able to get bigger, would she think on smaller times? Perhaps she longed for a return to that far-gone ago. Perhaps her reign as the Canyon Queen had lasted longer than a mind could take. Or maybe it was her way of avoiding the conspiracy swirling on the winds around her—the quiet scheming of the large pack of male Wadi banding together to do at once what no single male had done for thousands and thousands of sleeps—

••••

Not here.

Why? The male Wadi craned his neck around and looked to the circle of light at the tunnel’s entrance. The drippings from no less than three watering holes could be heard simultaneously, and the echoes of several deep interconnected passages swallowed his claw clicks with ease.

Is it not perfect? he scented.

The young Wadi flicked her scent tongue out. It reeks of death, she complained.

All these canyons reek of death.

But this is recent. Bad things happened here. I can almost see them.

The male Wadi tried his best to smell these things, but his mate-pair’s tongue must’ve been a thousand times keener than his own. He noted the tinge of spilled blood, but he felt certain he could tease that odor out of any of the rock they’d covered for the past hundreds of sleeps. It was everywhere, which surely made this warren as good as any.

At least for the night, he scented softly. Let’s drink and stay one night.

He meant to suggest other things as well, but it was hard to know if those yearnings drifted on the winds or stayed welled up inside him.

The one night, his mate-pair relented, and there was the smell of some exotic sweetness wrapped up in her thoughts that seemed to suggest other sorts of relenting. The male Wadi soaked his tongue in the hints, his body tingling with a love and joy made weary during their long jaunt to wider canyons. Made weary, but somehow made much deeper.

Rest here, he scented. I’ll get water for us both.

Water and a secret surprise, he added to himself.

He ran back through their new warren to the largest of the three shafts, the one that held a steady drip. In this place, cooler air rising up from the bowels of the earth collected as beads of water on the rock above. It ran down, chill and clear, rubbing indentions into the wall of the shaft. The Wadi stuck his snout below the lip and sniffed deep. The solid food-treats of rock sliders could be smelled below. The Wadi tested his claws on the edge of the watering shaft, found they bit deep enough, and so he scampered over the edge and down.

A cold upwell of air surrounded him, the moist walls reflecting the chill deep into his bones. The Wadi dove further, crossing another tunnel that smelled occupied, then another under dispute, and suddenly he was below the canyon floor, deep enough to escape the comforting warmth of the sunlit rock above.

He had only been down past the Wadi warrens once before, and quite by accident. The treats he had discovered and brought back had pleased his mate-pair to no end, but she had never let him risk a return trip. Now, though, with the potential of making her with eggs, he thought the gesture was worth the cold. Especially for the nourishment it might bring their brood.

The sudden slip of a claw returned the Wadi’s focus on the climb. He was far enough from the light for his eyes to be blinded, leaving just his wagging tongue to show him the way. The cold already made his joints stiff, his heart racing to keep his insides warm and moving. He knew from that long-ago day of giving the blue hunters chase—and also from his near-dying fall below the canyon floor—that the cold was a danger. The key was to move fast and full of purpose, to know one was going to survive the ordeal. He had never known that before and had gotten lucky. This time, he would be swift and knowing. He would just grab a few.

The shaft twisted near the bottom, curving flat before jogging to one side. The Wadi kept to the roof of the tunnel, keeping out of the flow of gathering water. He released a soft trail of scent behind to mark the way out.

The crackle of rock sliders could be heard ahead of him. He tasted the air, took a turn, then dove back down as the shaft deepened. There were more sliders further in the shaft, but he wouldn’t be greedy. He flexed his fingers, shaking the cold out of his joints. The numbness was already in the tip of his tail and growing toward his legs. He hoped his mate-pair wouldn’t worry—

There! Two sliders, maybe three, clacking back and forth.

The dead husks of the small, black creatures were often found in the lowest warrens. The male Wadi had sniffed from neighbors that they were known to clean the skeletons of dead Wadi. They had certainly seemed intent on doing something like that when he had fallen into their midst many sleeps ago. The eating, however, had eventually gone the other way around, as the rock sliders proved to be tasty morsels once their teeth had been removed from his hide.

The Wadi crept forward, balancing haste with the need to be silent. He clung to the ceiling and crawled out over the gathered bugs, homing in on their scents and persistent clicks. He readied himself with courage smells, ignoring the cold swelling in his bones. Before he could reconsider, he released his grip, spun in the air, and fell claws-down across the small creatures.

The rock sliders erupted in a mix of hiss and clack, their little teeth buzzing within their hard, shiny shells. Two of them bit into the Wadi’s belly and held tight. A third attempted to flee, but the Wadi slapped it with his hand and brought it close. He moved it near his soft belly until the rock slider’s teeth sank deep.

He had them. Or they had him. Either way, it didn’t matter—he knew from experience that the buggers wouldn’t let go. With claws he could barely feel and muscles stiff with chill, he turned and ran back through the deep tunnel, following his scent trail around and up, running and scampering until the smell of his mate-pair began to intermingle with his own harried scents.

••••

Where did you go?

The young Wadi forced herself to scent the question calmly. Her mate-pair had dashed off amid a dizzying cloud of fondness and returned cold and trembling. He responded to her question by rolling to his back and reaching for the black critters—each one as big as his fist and attached to his belly.

Why? Whywhywhy?

She reached for one of the rock sliders and wrapped two sets of claws around it; her mate pair was leaking a bit of blood around the creature’s bite. With a loud crunch, she broke the shell of the thing, forcing it to let go. She reached for another while her mate-pair worked to extricate the third.

For you, he was scenting.

Silly, silly Wadi.

She couldn’t help but release the thought. The last two bugs came free with the pop of their shells. In the dim light of the tunnel entrance, she could see the rows of tiny holes in her mate-pair’s flesh, all leaking the barest amounts of blood. It was all too often that his behavior confused her, and just as often that she found herself drawn closer to something she couldn’t understand.

They’re for tonight, he scented. They’re for our eggs.

The young Wadi shivered as soon as the thoughts tickled her tongue. She forgot the dying rock sliders and pressed herself against her mate-pair. She forgot the scent of death hanging in their temporary home and rubbed her scales against his. She forgot the blood on him, the need for water, the need to remain aware, and just lost herself in the yielding. In the pleasure—

What was that?

She froze. The shivering cold in her mate-pair had subsided, but she could still feel the chill in his bones. She sniffed the air, but didn’t quite smell—

There!

What is it? she scented, masking the ire at the moment’s interruption.

Something is coming, her mate-pair scented. Something—

But he didn’t finish the smell. The thought remained, half-formed and drifting, masked by the terrible odor of death come amongst them, the ripe and powerful stench of their warren’s owner preceded by a whiff of his foul thirst for blood. Both odor and Wadi were heading their way, blazing down the freshly scented trail her mate-pair had left in tiny, wet, crimson paw prints.

Run!

They both scented out a cloud of it. A cloud of scampering to safety so thick, it was hard to tell where one of their thoughts ended and the other’s began. The ideas swirled into one nasty vision of darting ever deeper into the growing and more dangerous canyons.

A surge of pure fright coursed up the young Wadi’s back from the tip of her tail to the base of her neck. The scent of death and aggression that billowed up after them was not new. Twice before they had taken up residence in another’s warren, and twice they had escaped by the width of a claw.

She ran, legs stretching to their fullest. She reached ahead for the rock, dug in her claws, and pulled herself along. She took turns at random, as her fear and racing mind dictated. She passed watering holes and occupancy smells and dreams of someone else’s eggs. She flew through all the scents, chased as she was by an explosion of rage, of black thoughts so frightening and thick, they threatened to drown out all else.

They even smothered the fact that she was now running alone.

The Wadi stopped. She peered through the darkness behind her, searching for her love, for his moving dull brightness amid the black. She sniffed the air for her mate-pair, but his trail had thinned to nothing.

A new fear grew inside: a hollow powerfulness that threatened to consume her, an untarnished dread as bright and vivid as any emotion she’d ever scented. She teased apart the constituent molecules, trying to understand this novel horror—

It was the potential of being alone in the world, she realized.

The young Wadi turned and raced back along her route, following her trail of fear and sniffing for her mate-pair. She scrambled back through the egg-dreams and occupancy odors and over the watering holes. She hurried back toward the smell of death, a smell that had—

The Wadi came to a stop. She shivered uncontrollably.

A smell that had—

She opened her mouth and wailed into the dark tunnel, emitting a scream to outrace her thoughts. She dug her claws into the rock and threw her chest into the mad cry, allowing it to echo through the stone and race down the tunnel. She yelled and yelled to drown out the smell, a smell of death that had grown stronger. More vivid.

And more achingly familiar.

000

The Canyon Queen stood frozen by the mouth of her warren, her eyes moistened with old memories. There were some days when the long-ago seemed but a sleep or two away, when her scent tongue could probe her memory sacks and conjure visions as fresh and bright as the view of the suns-lit canyon before her. There were other times when the noise of so many smells from other Wadi made it hard to tease out what had happened in her lifetime and what were the latent memories of all those around her.

She forced her great muscles to relax as she sniffed the cloud of nostalgia for the brighter trails: trails of companionship, of longing and loving, of egg-dreams and playful scampering. It was these recollections, drawn out every so often, that had kept her going through the thousands and thousands of sleeps after his death. They had kept her wary of taking a new mate-pair. They had given her the strength to push ever deeper into the canyons, bringing those twin lights higher and higher, the shadows shallower and shallower. Those good memories had done much over the sleeps. They had even helped her do bad things. Helped her kill. Helped her survive. Helped her grow bigger and stronger than any Wadi in all the memories stirring on the winds.

And she would keep growing, she knew, as long as she never took a mate-pair. As long as she stayed eggless, with nothing to feed, nothing to grow outside of her, she would grow and grow until—

But even she didn’t know.

She sniffed the air, hoping for answers, but the bright fog of her past still lingered and occluded the thoughts beyond. Her warren, situated as it was directly below the twin lights, was an area to which answers tended to drift. It placed her at the center of what she now knew to be a half-lit sphere, a world that went all the way around. That was one of the many answers that had drifted to her on the breeze. Another was where the wind came from—or more precisely, where it went. The hot air directly over her warren was always surging up, taking her thoughts and the thoughts of a billion Wadi with it. The wind rushed from all around her egg-shaped world, pushing toward her warren and away from the cold and dark before rising up toward the great twin lights. Somehow, those lights sucked and sucked at the air and never breathed it out. They pulled the winds up with the heat, dragging the scents of billions with them as they passed.

And the Canyon Queen lived at the heart of it all. She had lived there for thousands and thousands of sleeps, sniffing the air with every spare moment, looking amid all the countless answers for the one that wouldn’t show itself. The answer to her great and sorrowful: Why?

It was this vigilance that had kept her sane, had filled her with many other answers, and had kept her alive.

But it would be her current fog of deep rememberings, her thoughts of long-ago, that would doom the great Wadi. For it was then, with her senses numbed by a cloud of recollections, that the band of males came with their schemings.

It was then that they came to rape their Queen.

••••

They arrived in a number higher than counting, a number not needed for any Wadi purposes and therefore a number without name. It was more than the biggest number the Canyon Queen had in her head—two or three or ten times that number. When the first rows stormed her warren, they brought with them the awful smell of their mad plans. They reeked of the many closing in behind. Gone were their odors of occupancy and territory. Gone was the male competition. They had banded together, their thoughts intermingling. They had become something new and terrible and fully worthy of her fear.

The Canyon Queen snapped the necks of a few, their male bodies as big as males got, no more than the size of her arm from elbow to claw. She could kill two or three at a time, one in each paw. A sharp squeeze, a snapping like brittle rock, a flood of death smells. But the waves of the living kept coming after.

Claws sank into her back. Teeth wrapped around one of her great ribs. The Canyon Queen shrieked, her skull ringing with the sound of her own voice, and everything seemed to pause for a moment, taken aback by the mighty roar.

And then it resumed.

The Queen threw her body into the rock, crunching the male on her ribs. She swiped her tail in the darkening confines of her warren, swishing a Wadi off her back, his claws raking her flesh as he went.

One of the Wadi moved to fill her with eggs. She felt a cold sensation, felt her thighs buckle, her knees clench to her chest, her tail tuck protectively. She roared again and spun around, meeting the wave of Wadi pouring in through the back of her warren. She kicked the male off her flank, her body convulsing as his egg-dreams invaded her nostrils. Her scent-tongue became useless for any other danger. It remained in its pouch, sullied and hidden, as the lights from the canyons were finally extinguished by the writhing masses pressing their way inside.

The Canyon Queen began to kill full-grown males with wild abandon, cracking them like so many rock sliders. She crushed them, and more appeared. Their bodies soon packed all around her, each victory bringing more confinement. No matter which direction she faced, there were those with egg-dreams attacking her flank, hoping to dwindle her with their insemination, hoping to drive her off to the shallow canyons where she’d grow her eggs and die.

Tiny claw after tiny claw bit into her flesh, the thousand small nicks merging into a web of fierce wounds. The Queen slipped in her own blood. One of her legs became pinned beneath her. More Wadi pressed in—the Wadi of a thousand warrens, drawn together by some scent of desperation. They crowded her. They sank their claws and teeth and worse into her. They packed themselves between the walls and her cut and leaking body. They stirred and slithered through the jumbled mess of dead and dying, and they took their turns with her. They were violent and rough. Feral. Mad with their victory and with the stench of the dead all around them.

The great Wadi’s head became buried under those she had killed. She was no longer able to unclench her paws to add to their number. She whimpered, barely able to breathe. Tears of pain squeezed out her eyes. She choked on the horrid stench of it all as the males filled her with their egg-dreams.

They filled her, and they clawed her.

And she was the Canyon Queen no more.

0000

It’s her.

Let her pass.

We should help.

Don’t go near her.

The thoughts stirred through the canyon hollows and swirled around the Wadi, her body still laced with scars. She ignored them and drank from the watering hole. She drank until the rivulet ran dry, her powerful thirst refusing to step aside like all the thousands of Wadi she’d run past on her dwindling, egg-filled journey. Rumors of her coming and of her past ran upwind faster than she could travel. Legends were growing of the eggs she would lay. Legends she aimed to prove false.

That way.

Take this turn.

Use my home, I beg.

My birth warren is best.

The directions and pleadings were scented in feeble tendrils, choked back by the shared and ancient fear of her. She ignored them all. Her body was dwindling, returning to its birth-state as it prepared to give new life, but she had no intention of seeing it through. Her physical self could waste away, but nothing would take the memories lodged in her mind—the trillions and trillions of scent molecules saved up over thousands of sleeps of looking for answers. There was one there—one answer stolen from the winds—that she never appreciated until now. It was the tale of an eggless canyon, where something in the rock made females sterile, where few Wadi dared to live but many went to die.

And that’s where the worn-out Wadi would go: to the canyon where the blue hunters never came, to the land of the crazed females who arrested their dwindling to live in solitude and sorrow. She would travel there before the eggs came. She would go mad there before her brood could come and take her awful memories as their own. That would be her revenge against the males who raped her, who had done so many awful things, none of which were more hideous than having allowed her to live.

The Wadi drank her fill, practically feeling herself shrink as she did so. She cursed the need to pack away energy, storing it in parasitic eggs that would one day hatch as she lay dying. She drank her fill and moved on, ignoring the whispered scents of those around her who pleaded with her to reconsider her plans even as they scurried out of her way.

••••

Many sleeps went by. The periods of walking between each sleep were just as dreamlike and hazy. The Wadi had lived two lifetimes before; this was her third. There was a lifetime of loving and growing, a lifetime of powerful surety and haunting questions and thin shadows, and now a lifetime of wasting away. It seemed to her that many of the things that had happened in the past must have happened to some Wadi else. The fresh pain had long ago become dull aches. The dull aches had long ago become stiffness in her bones. Her bones had long ago begun to feel brittle and weak, not capable of holding such aches and pains. She could remember bad things happening to her.

She tried to pretend they had happened to some Wadi else.

••••

When she arrived, the Wadi found the eggless canyon a stagnant place, a near-odorless place. She had to strain herself to scent the life in the adjoining canyons, as it was feeble even there. Occasionally, a whiff of normalcy would invade, of eggs laid and Wadi living, but the winds would carry them off just as quickly, leaving behind the nothingness she had travelled so far to find.

She was vastly smaller than her former Queen-self. She knew this despite the matching warrens and canyons, which had shrunk along with her. She could feel it in the tightness of her being, in the sensation of an entire form packed into the size and hardness of a single claw.

Bending close to the rocks, she sniffed deep. The stone revealed traces of those who had come before her. Their old smells lingered longer than she thought possible, untrampled by the scents of the boisterous living.

She spent her first few sleeps teasing out stories from the past. Stories of hunters—not blue for some reason—stalking the lifeless canyon once an eon or so. She scented stories of sadness similar to her own, of Wadi without hope coming to a place where they could wither in peace. She sniffed deep from the cool rock, finding answers in the small eggless place that had eluded her when she ruled all. She found more truth in that quiet sadness than she had uncovered in her days at the apex beneath the full glory of the twin lights. She found more in common with these other Wadi, her sisters in time, who had lost everything but their desire to remember and be remembered. Here was the land of the pair-less, of those whose bonds had grown so strong, when broken they could not be mended.

The answers finally came, and the Wadi knew she was home.

The poison in the rock soaked deep, slowing her descent into nothing.

They soaked deep, antidotes to the egg-dream poisons within her.

••••

It felt like many sleeps later that the hunters came, the ones of the occasional eons. They were not blue, like the tales of so many. Not blue like the story her mate-pair had told her. They were pungent with different smells: odors of confusion and fear.

She sniffed one hunter’s progress as he went deep down the winds, his mind leaking thoughts of large Wadi dead, but leaking them with a thirst the old Wadi found sweet on her tongue. There were thoughts of a mate-pair in this hunter’s mind. She sniffed him go deep into the canyons until his scent was gone. She did not welcome this intrusion of questions into her realm of answers.

More of the alien hunters came not long after. One smelled foul, his desires leaking like black smoke full of pilfered eggs. His trail came feeble but stark as it worked its way over from a neighboring canyon. The Wadi marveled at the lack of response from her brethren. Could they not smell this?

By the time they did, it was too late. Many canyons away, an egg was stolen. The black thoughts swirled with joy and ire.

The Wadi stirred, this intrusion shattering the sameness and ageless sleeps. She moved to rouse those in her adjoining warrens, when one of the not-blue hunters entered the eggless canyon. Columns of multi-hued thoughts snaked down the winds ahead of her, ahead of this frightened and weary hunter. The old Wadi scented them deep, confused not by the alien nature of the mind leaking them, but by the familiarity.

She left her watering hole and followed the smells of this hunter, tracing them through the porous rock. There was something in them that matched her long-ago life. Her first life. Something of hope and happy not-knowing. Something of excited fear, rather than the fear of dread. Something of passion, even if the molecules didn’t quite fit her tongue’s receptors. And then she knew what it was: It was the hunter’s thoughts of a mate-pair that had the Wadi scampering from disused warren to disused warren. There was something in this alien’s emanations that reminded the Wadi of herself. A long-ago self the males hadn’t killed, had barely even clawed. A younger Wadi with an aching, hopeful heart.

She paused to drink from another hole, and that’s when the odors changed. There was a fight. Wadi and alien fear mixed in the air as the two clashed. One of her mad egg-less neighbors had been attracted to the same scent, that odor of hope and pure new bonding like an antidote to their poison. The hunter with the mate-pair thoughts became injured. Injured and running, the fear no longer excitement, but dread. The old Wadi ran through the tunnels as well, chasing that previous scent, that good scent, and trying to win it back.

She ran through warren after warren, her claws clacking the rock, her arms and legs growing weary. Thirst consumed her, but still she ran. She followed the mad dash of the hunter with the pure smells, now tinged with fright. She tried telling the creature to stop, to give up more of the memories, more of the long-ago.

And the hunter did stop, seeming to hear her pleas.

The hunter stopped and rested against the rock. There were pure thoughts again—the hunter was dripping with them. The Wadi crept closer, sniffing the thick emotions. She rounded a bend to find light filtering into the mouth of a tunnel. The canyon beyond was bright with the glow of the low twins and groaning with the wind passing through. The Wadi moved closer, and then something moved into the mouth of the tunnel. A white something, still and lifeless. The Wadi sniffed the air. She could smell the moisture in the thing, this ball of crumpled white, but more than that: she could smell the hunter’s delicious thoughts. The white thing was laden with them. Dripping with them. Tempting and tasty and dangerously full of hope.

The Wadi laid out on the cool rock, her belly warm and quivering from the long run. She lay there and watched the white temptation, wondering what it would do.

Wondering what she would do.

Part XVII – Escape

“What good is the running, with nothing to run to?”

1 · Lok

Three sets of landing struts settled to the packed soil of the Lokian forest, one of them squeaking slightly, in need of oil. Molly looked out through the carboglass where large shadows danced at the edge of a wooded clearing, the black puppets thrown high and wavering from the light of so many campfires. Her mother’s voice continued to drone in her helmet’s speakers, complaining and asking questions about Molly’s refusal to jump to hyperspace. Molly pulled her helmet off and closed its visor, trapping her mom’s voice inside the dented shell.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered, apologizing for disappointing her mom and for not being able to explain herself. She placed her helmet on its rack and patted her Wadi as the colorful lizard settled across her shoulders.

Walter turned and faced her general direction from the nav chair. He still had his modified welding goggles on for the jump to hyperspace, which meant he was practically blind.

“But we’re gonna go ssoon, right?” He waved his hands out at Molly, the black goggles contrasting with his silvery skin and making him look comical.

“As soon as we can,” Molly said. “I promise.” She laughed. “Until then, you can take those off.”

Walter hissed his annoyance but reluctantly removed the goggles. Molly wasn’t sure why he had been so eager to dash off to hyperspace to rescue Cole and her father, but he seemed nearly as miffed as her mom about the sudden change in plans.

Even with the visor closed and the volume down, Molly could still hear her mother’s muffled questions raining down from the rack behind her. She felt horrible for not explaining herself better. She felt even worse for not fully understanding the decision herself. As much as she longed to rush off to Cole, as hard as she’d struggled the past weeks to secure the fusion fuel necessary, when the moment had arrived with her finger on the button… she just couldn’t do it. She couldn’t leave the Callites behind who had lost so many family members to Bekkie’s blood-draining operation. She couldn’t abandon Saunders and his crewmen, who had survived a shipwreck that had spared so few. Molly tried not to think she was throwing her life away in a futile gesture of heroism, some primal urge to strike out at the Bern ships that had tormented her home planet from orbit, but given the odds that her return could do any good, there were few other interpretations.

Her Wadi licked the air contentedly as Molly powered the ship down and shut off the flight systems. The colorful lizard from Drenard seemed to be the only crew member left that wasn’t upset at Molly’s decision. She patted the animal on the head and moved to step over the control console, leaving Walter to fumble with his harness. As she hurried back through the cargo bay, Molly began working on an explanation for Saunders and the others as to why she had chosen to stay.

The cargo ramp creaked out into the Lokian night, and then lowered toward the dew-soaked grass beyond. Molly watched as a clearing full of curious faces were revealed by the descending plate of steel. Cat was the first person to come inside. She jumped to the descending ramp before its lip even reached the ground.

“You forget something?” the Callite asked, a wide smile across her dark, scaly face.

Molly ran down the ramp to meet her, and the two women squeezed each other’s arms. “I just couldn’t leave,” she said, the simple truth slicing through a hundred half-forged excuses. Molly looked over Cat’s shoulder to see Scottie and Saunders stomping up the ramp behind her, their faces scrunched up in confused smiles.

“Besides,” Molly said, “I think I have an idea.”

“What kind of idea?” Saunders asked, stepping up to join them.

Molly looked from the Navy Admiral—her former superior at the Academy—to Scottie, the old illicit fuser and new friend. The two men represented opposite ends on as wide a chasm as law could allow. Molly wondered how best to speak in front of both of them, how to explain her plan without divulging any secrets about Parsona’s illegal hyperdrive—a drive that could move things across the galaxy without a care for what got in the way. Saunders wouldn’t enjoy hearing those details, and Scottie would probably be miffed to hear how much her plan relied on Navy skills and tactics. Molly looked from one of them to the other, not knowing where to start.

“Does this mean you’re not rushing off to hyperspace?” Scottie asked.

Molly shook her head. “I’m staying. For now.”

Saunders pointed up. “Does this plan involve attacking those bastards up there?”

Molly nodded.

“This is gonna be like one of your crazy simulator stunts, isn’t it?” Saunders smiled and crossed his arms. “Well c’mon, let’s hear it.”

Molly held out her hands, trying to slow both of them down. The risk of revealing her hyperdrive to Saunders had won out in her mind—she couldn’t do it, so she needed a cover story of some sort.

“I have a few details I need to hammer out with these guys first,” she said, nodding to Cat and Scottie. She looked over her shoulder as Walter padded out into the cargo bay, his goggles down around his neck. “Besides, it’s already late, and it looks like you still need help distributing the food and water. Let’s tend to the Callites. I’ll talk to my friends later tonight, and we’ll meet with you in the morning.”

Saunders frowned. “I don’t like being left out of the discussion,” he said.

Molly stepped closer, wary of the crowd gathering around the ship, eyes and ears wide. “I know,” she said softly. She felt sorry for the Admiral, imagining how helpless he must feel with nothing to do for the paltry few survivors of his once-powerful fleet. He couldn’t even speak freely among his staff now that she’d told him of the Bern threat and the stark physical similarities between them and Humans.

“Look,” she told him, “I really need you to trust me on this.”

Saunders seemed about to argue, but his frown cracked into a wan smile, his fat jowls lifting just a little. He squeezed Molly’s shoulder and looked out over the two groups of haggard survivors in the clearing.

“I suppose I owe you a little trust,” Saunders said, referring perhaps to having doubted her before and having thrown her in jail. The old man turned back to face her, his eyes wet and reflecting Parsona’s interior lights. “And I’m glad you decided to stick around,” he said, forcing a smile.

Molly nodded and smiled back. She suddenly sensed just how much he meant it, this man who had once expelled her. And for the first time, her decision to stay resonated within her as having been the right choice.

••••

There was no sleep that night as Molly and her friends stayed up and discussed her germ of a plan for dealing with the Bern fleet. They huddled together around a campfire built under Parsona’s starboard wing and nurtured the idea, watching it sprout and grow as they each offered suggestions and pointed out various flaws. They spoke in hushed whispers, and even by the standards of Bekkie’s short days, dawn seemed to arrive in a rush.

Morning was heralded by the popping of rekindled fires within the woods as early risers awoke to stoke dying embers. Gradually, the first smattering of Humans and Callites emerged from their scattered camps; they crossed the clearing on weary legs, looking to Parsona for some odd supply item or just for the use of its bathrooms. Molly greeted them and made them feel welcome, even as Walter cast suspicious glances their way.

When one of the Navy crewmen exited Parsona with a load of fresh laundry, Molly asked if he would send for Saunders, and the crewman agreed.

“Are we sure we’ve got our story straight?” Molly asked. She rubbed her weary eyes and looked to her friends around the fire, each of them nodding with as much enthusiasm as they could muster despite their lack of sleep. Leaning forward, she grabbed a pot of coffee from a flat stone near the fire and topped up her mug. She hoped the jolt of caffeine would help her regain some energy before the day’s plan was spelled out and acted upon.

After a few minutes, Saunders arrived alone, his sagging jowls and dark-rimmed eyes signifying a similarly restless night. He lowered his considerable bulk to one of the blankets and eagerly accepted a cup of coffee, wrapping both meaty hands around the steaming mug. Cat said hello while Scottie greeted the old Navy veteran with the sheepishness of an outlaw waving to a passing sheriff. Walter didn’t even acknowledge Saunders’s arrival; the Palan boy sat across the fire from Molly, continually poking the logs with a stick to send out showers of rising embers.

“You ready to tell me about this plan of yours?” Saunders asked. He blew across the surface of his coffee, sending a wisp of heat toward the fire.

“Yeah.” Molly took a sip of her own coffee and thought about where best to start.

“And what is this plan for, exactly?” Saunders asked. “Will it help stop the Drenard attack? Or is it just for the bastards who shot down my fleet?”

Molly raised her eyebrows. “It’s for all of it. Hopefully.”

Saunders smiled. He took another loud sip from his coffee and waved one hand in a small circle, pleading for her to get on with it.

“My friends here,” she indicated Scottie and Cat. “They know something about these rifts, these tears in space like the one the Bern fleet is coming out of.”

Molly took another sip of coffee, steeling herself for the half-truths that were to follow. “These rifts are everywhere,” she lied. “There’s even one very close to us, right here in these woods, and my friends know how to control it.” Molly chose her words carefully, using the language she and the others had decided upon in order to not reveal the special properties of Parsona’s hyperdrive.

Saunders glanced across the fire at Cat and Scottie. He raised his eyebrows. “Control it?”

Molly nodded. “We can send people through this rift to wherever we like.”

“Wherever? You mean like through hyperspace?”

“Yeah. It’s similar, but without the limitations.” Molly felt a wave of nausea as the lies piled up. Creating a fairytale to keep her hyperdrive secret was going to become burdensome, and fast.

“The thing is, travelling through this rift is a one-way trip,” she said, which wasn’t a lie. She forced herself to meet Saunders’s gaze “We’ve got a plan for how we can make life miserable for the Bern.” She waved her arm toward the edge of the woods where the surviving members of Gloria’s crew were mingling and working to improve the encampment. “We have enough pilots,” she said. “We just need a fleet, right?”

Saunders shook his head, his jowls jiggling back and forth. “Are you crazy? Did you see what happened yesterday? This is not the Tchung we’re dealing with. An entire Naval fleet is scattered across this planet in utter ruin—” Saunders held his mouth open as if to say more, but Molly could see his cheeks twitching, the tears welling up at the bottoms of his eyes.

“I know, sir, just hear me out. The fleet I’m thinking of will give anything a run for its money. It’s the most battle-tested fleet of ships in the entire galaxy.”

Saunders frowned. “More powerful than Zebra, the most advanced fleet in the Navy’s arsenal?” He waved his mug in the air, sending a dark wave of coffee over the edge. “Such a fleet doesn’t exist!”

“It does at Darrin,” Molly said, keeping her cool. “It’s the one place in GN controlled space that even the Navy can’t go.”

Saunders laughed. He set his coffee in the dirt and wiped his palm on his too-small flightsuit. “Darrin? And what fleet do you suppose we’ll use to get that one? They would make even quicker work of us than the Bern did!”

Molly shook her head. “No, we don’t use a fleet. We use the rift. Don’t you see? We send people straight to the ships. We can place teams inside Darrin garages and nab a fleet right out from underneath them!”

Saunders chewed his lip. “Too many problems. For one, even my StarCarrier doesn’t have chart data for Darrin that accurate, so you’d be lucky to end up anywhere near one of their hideouts. I mean, nobody legit has been there since their civil war, and besides—”

“My nav computer has the entire system scanned from just a month ago,” Molly interrupted. She jabbed a thumb back toward Parsona.

Saunders shot her a look that suggested this wasn’t something to brag about.

“Then there’s the pilot codes to consider,” he said. “Nobody leaves their ships unlocked—”

“These guys do. They trust their forcefields way too much. I—well, I kinda flew one of their ships back to Earth the day that… you know, with Lucin—”

“Are you kidding?”

Molly raised her hands. “I swear on my father, I did these things with the best of intentions.”

Scottie leaned over to Cat and whispered loudly: “She sounds like one of us, now.”

The two of them snickered. Molly was so tired, she nearly joined them.

“We would need weapons,” Saunders said, ignoring the others. “The ban on Lok is going to make that difficult—”

“Covered, and it’ll actually be the most unpleasant part of our plan.”

Saunders reached again for his coffee. “Which is?”

“We raid the StarCarrier, sir. We send in a team with climbing gear to rappel down to the armory. You’ve got the access codes, and we need to grab enough flightsuits for the pilots, anyway. I’ll take a small group in my ship to do this while you brief and prepare the others. Some of them might not feel like they’re ready for this kind of raid, but we’re gonna need everyone. You’ll have to make them believe this’ll work.”

“But will it work?” Saunders looked into his mug, staring down at it like an oracle searching a muddy well. “Lok and Darrin are on opposite sides of the galaxy,” he whispered. “If this rift of yours can get them there like you say, it’s still, what, five days flight time to get them back?”

“Actually, sir, I think it can be done in three days. We plotted it out last night on our charts. It requires skirting the galactic center and quick-cycling the hyperdrives each time, but—”

“The hyperdrives will be toast if you quick-cycle them three jumps in a row,” Saunders said.

Molly nodded. “I agree, that’s why—”

“It’s gonna be a one-way trip in both directions, Admiral,” Cat said.

Saunders mulled this over. He looked out toward the edge of the clearing where his people and the Callites were making breakfast and consoling one another for their losses.

“Most of my people haven’t flown a real mission their entire careers,” he finally said. “I’ve got maybe twelve decent pilots over there.”

“Thirteen, including you,” Molly said. “And several of the Callites can fly. The rest will be needed for adequate crew on each ship, and to help during the raids on the Darrin asteroids. Besides, they should be more comfortable behind the stick by the time they get back here. We’ll have them drill some maneuvers on the way.”

Saunders shook his head. “I don’t know. And what’s all this you nonsense? You’re coming with us if we do this. We’ll need you most of all.”

Molly shook her head. “No can do. I’m gonna be busy while you guys are gone.”

“Doing what?” Saunders asked.

“Taking out that big ship,” Molly said, glancing up.

“That small moon up there?” Saunders’s eyes widened.

“Yeah. We think it’s what knocked you guys out of orbit.” Molly nodded to Scottie. “The Callite shuttles from Bekkie didn’t start going down until after it arrived. We think it can control gravity fields in a localized manner. We’ll need to destroy it before you guys come back from Darrin, otherwise you won’t stand a chance.”

“And how in the galaxy are you planning on taking it out with just your one ship?”

“Well—” Molly took another sip of her coffee. “After we send you guys out to Darrin, we’re gonna go back to the StarCarrier.”

“What for?”

“For all the Firehawk missiles my ship can hold.”

“And you’re going to fire them, how?” Saunders frowned. “Have you got any Firehawks I don’t know about?”

Molly shook her head. “We use the rifts,” she said, stretching the truth once again to protect Parsona’s hyperdrive. In reality, she didn’t plan on carrying the missiles out at all. Instead, they would send them up from within the StarCarrier, where she and her friends would be safe and out of sight.

Saunders crossed his arms. “And I suppose these rifts are going to arm them for you as well? Or do you have some magical ability to remotely detonate Navy missiles?”

Molly smiled. She looked across the fire and gave Walter a wink.

“We’ve got it covered,” she said. “And it’s probably best you don’t know.”

2 · Hyperspace

The ready room of the Drenard Headquarters buzzed with the accented whispers of a dozen alien races. They stood in five lines and prepared themselves for one final raid across hyperspace. Cole Mendonça stood amongst them, wearing the same sort of white combat suit as the others and nervously gripping his buckblade. He stared down at his feet, at the dull path worn into the steel beneath them, the sign of many thousands of boots shuffling forward on previous raids.

“Good luck,” someone behind him said.

Cole turned and nodded mutely to Larken, his group’s translator. Larken squeezed Cole’s shoulder, then patted it twice.

Cole glanced over at Mortimor, who had just given a last series of instructions to the five squads before joining the group lined up beside his.

“I didn’t know you were going,” Cole said.

“Ran out of people who speak Bern.” Mortimor nodded toward the row of hyperdrive platforms in front of them where the five pilots sat, their arms wrapped around their shins. “Now pay attention,” Mortimor said.

Cole nodded and focused on the platforms. A moment later, the light over each pilot switched from red to green. There was a loud beeping sound from the row of control consoles followed by a pop as the five large cages in the back of the room—cages Cole had designed and helped build—vanished.

A moment later, the pilots followed, winking out of existence with a muted pop, as air from the room crashed together to fill the void they had left behind. The row of navigators jumped up to take their place on the platforms. They turned, fell to their butts and tucked their chins, only having three seconds between jumps to prepare themselves.

Cole glanced over at the navigator in Mortimor’s line. A lock of bright red hair spilled out of Penny’s hood as she settled into place. Her eyes met Cole’s for a brief moment just before her head went down. There was a soft pop, and she too disappeared from the room, leaving Cole awash in a tremble of nerves.

It was all happening so fast.

Cole’s heart missed a beat as he took a step forward, shuffling the steel decking ever duller. He chanced a glance to the side at the neighboring line. Mortimor was looking straight ahead, the man’s beard and combat hood hiding whatever he was thinking. Cole wished he’d known Molly’s old man was going on the raid. He would’ve switched places with someone to be in Mortimor’s group and been able to keep an eye on him—

The lines surged forward again. Cole felt Larken’s hand on his back, pushing him along. Suddenly, Cole found himself beside the console operator, right in front of the jump platform. Marx, the Callite swordsman who would help Cole clear the Bern ship’s corridors, plopped down on the platform. The alien looked up and time slowed down to a crawl. Cole watched Marx’s arms wrap around his shins, saw the man’s scaly chin tuck against his knees—and then the alien was gone. More air crashed together so close, Cole felt the sucking breeze on his cheeks. He jumped up to the platform and sat down as quickly as he could, then spun around to face what he hoped would be an exit once he popped inside the steel cage. In the back of his mind, he counted:

Three.

He grabbed his shins and tucked his head, squeezing his buckblade as tightly as he dared without crushing it. A thousand sword fighting tips from his practice sessions with Penny flashed through his mind.

Two.

A sickening sensation clawed at Cole’s stomach as he wondered if the raid was a mistake. He tried to remember what the Seer had said about free will, but then the silent counting in his mind clicked down to—

One.

•• 2 ••

The ready room of the Underground Headquarters disappeared. One moment, Larken was standing before him, looking down at his sword and waiting his turn. The next, Cole was seeing the interior of a metal box. He fell half a meter out of the air and landed on his ass, smacking solid steel. Cole felt a rush of adrenaline—the raid had really begun! He sprang forward and launched himself through the clean hole the pilot had cut in the side of the cage. It was a couple meters to the ship’s deck below. Cole hit the plating in a roll and looked around.

Marx stood off to starboard, his buckblade drawn. The Callite turned and glanced over his shoulder at Cole.

“Go,” the alien said. Marx spun and ran down the corridor, looking for Bern crewmen to kill. Up ahead, Cole could hear the pilot and navigator stomping forward to secure the cockpit. Cole felt a sick lurch in his stomach as he imagined where they were: His squad had just jumped across hyperspace and into the belly of an enemy ship flying in formation with thousands of other enemy ships. He looked once more to Marx, but the Callite was already out of sight, disappearing around a bend in the corridor. Cole remembered his duty, that he should be running in the opposite direction. He spun and headed off, catching a glimpse of Larken as the translator leapt out of the suspended cage.

The image of the metal box stuck with Cole as he ran aft. Protruding from a solid bulkhead—twisted sheets of metal peeled back from the expanding grav plates—it had worked exactly as he’d imagined. No matter where the box had ended up in hyperspace, those expanding sheets of steel in its center would’ve provided a safe pocket of emptiness for them to arrive inside of. The first part of his plan had worked flawlessly. Cole felt a surge of hope wash away some of his anxiety. He was that much closer to Molly.

As he ran down the ship’s corridor—his thoughts straying from his duty—Cole finally remembered to flick off the safety on his buckblade. He reminded himself of the grisly task that lay before him: he would need to kill without hesitation.

He ducked through a passageway, the thick airtight door left open and secured to the bulkhead. There was a funny script of writing above the hatch in neat red ink, the shape and style of the language resembling nothing Cole had ever seen. The peculiar writing stood in stark contrast to the rest of his surroundings. Otherwise, Cole could’ve been running through a Navy ship. The size of the passageways, the spacing from ceiling to floor, even the height and ergonomics of the control pods on the walls—they were all identical to a Human craft.

Cole turned a corner and was reminded why this was so. The figure strolling down the hallway in his direction looked perfectly Human. Even the confusion and shock on the Bern’s face were familiar, and much easier to read than the red script had been.

The Bern crewman fumbled at his belt—whether for gun or radio or what else, Cole didn’t wait to find out. He continued his run and flicked on his buckblade, unleashing the molecule-wide wire made stiff by the hilt’s exotic magnetic field. He swung up in an angle four as the Bern pulled something from his hip—

The Bern’s head fell sideways, removed from his torso in a slanted wound from neck to ear. Cole danced out of the way, cursing himself for being so sloppy, and not just for the fountain of gore erupting from the Bern’s neck and splattering the wall, but the poor reflex of going for a soft spot. He needed to remember the power of the weapon he was holding. The goal was to aim for the torso, or anything difficult to miss or hard for the enemy to pull out of the way. There was no such thing as a “soft spot” for the buckblade. There were just spots. Any spot would do.

As the Bern’s body finished slumping to the ground, Cole gathered himself together. He took one look at his artificial arm, remembering the stakes. He then turned and ran deeper into the ship, stopping to check every turn, nook, and corridor.

He took his next two victims by surprise. Both deaths were uniquely horrific, but neither felt as personal as he’d feared they would. The blade slid through their bodies, and even some of the ship’s equipment that got in the way, without an ounce of resistance. It felt more like casting a spell on someone from a distance than a physical strike. All he did was wave a wand—and a body was split in two.

Cole took every right turn as he headed aft to make sure he covered the entire deck. He went through a dozen Bern in the process. He tried to remember Mortimor’s warning to do minimal damage to the ship with follow-throughs, a real concern when fighting in close quarters with buckblades. An accidental swipe could easily destroy something crucial in a ship they needed in order to escape hyperspace.

Rounding another corner, Cole nearly collided with Marx, who was jogging the other direction. Both swordsmen flinched, readying to strike—but they were able to restrain themselves. They stood in the passageway panting, splattered with alien blood, holding their invisible swords and smiling grimly at each other.

“Any stairs or lifts?” Cole asked, out of breath more from the adrenaline dump than the long run.

“No,” Marx said, his English accented with the coughing sound of a Callite. “Looks like a single deck design. Lucky we didn’t end up in mechanical spaces.” Marx nodded the direction Cole had come from. “Let’s get to the cockpit. Sweep your side again.”

Cole gave Marx a thumbs-up, then wondered if the Callite even knew how to interpret the gesture. “Gotcha,” he said, and ran off the same way he’d arrived. Once again, he couldn’t believe how well the raid was going.

•• 1 ••

The last thing Penny saw of the ready room was Cole, the poor boy’s face drenched in nerves. Then she closed her eyes and waited for the drop in her stomach, followed by the crashing down to the deck.

As soon as her butt hit cold steel, she launched forward, expecting to find a clean hole cut in the side of the cage. What she found instead was Jym, her pilot, pressed up against one wall and cursing at his clearly malfunctioning buckblade.

Penny felt a wave of panic; she barely remembered to jump to the side and get out of the way of her next squad mate, but self-preservation moved her just in time. She powered up her own blade and pushed it through the cage wall. As she began making a wide circle through the solid steel, she heard a pop of air behind her, followed by the sound of Stella gasping with alarm at the sight of the cramped cube, a cube that should’ve been empty.

Penny turned to warn her, to drag her out of the way, but it was too late. A few heartbeats later, Gregury jumped in and fused with Stella. The squadmates became a sickening, two-headed monster—half Serral and half Human. Screams of raw agony blared out of them both—fading to gruesome moans as intertwined organs ceased to function.

Jym threw down his sword and grabbed Stella’s boots. He threw his hands up, flipping the tangled mass of limbs backwards and out of the way. Penny pressed herself to the wall as Mortimor fell out of the air in a tight ball, missing by inches having some part of him fused with one of the others.

The screaming from Stella and Gregury fell silent. Penny thought about putting them out of their misery with her blade, but they were already dead before she could steel herself. Jym, the group’s pilot and therefore responsible for cutting an exit out of the box, cursed and kicked his dead buckblade in disgust.

Mortimor scanned the tight confines of the box and seemed to take it all in. He reached down and picked up one of the dropped swords from the two dead squadmates. “Jym, you go forward alone and clear the cockpit.” He handed him the retrieved sword. “Penny, you take Starboard. I’ll clear Port. Go!”

Penny nodded. Translator and navigator had instantly become swordsmen, she and Mortimor reverting to older, more comfortable roles. She finished her cut in the wall and kicked the center of the crude circle. The heavy steel fell away, exposing the Bern ship’s decking half a meter above the floor of the box. Two sets of legs stood there—Bern crewmen studying the strange cube that had appeared inside their starship. Penny swiped through all four limbs with a wave of her hand. She jumped out to the deck and silenced the screaming forms before they hit the ground.

It was a messy start, blood slicking the deck around the box, but Penny didn’t pause to help the others. She ran aft along the port side, thinking of the look on Stella’s face before Gregury had jumped in, and how different she had looked just moments later with her wide, lifeless eyes. The horrific sight—the suddenness of the switch from life to death—gave Penny fuel for moving swiftly through the craft, slicing down all the bewildered Bern who stood in her way.

•• 5 ••

The windshield of the impounded Bern craft was dusted in a never ending torrent of snowflakes. The flurries impacted right in front of her and slid to the side, gathering in miniature drifts. The sight of the stuff, coupled with the harsh whiteness beyond, made it easier to fly by the instruments than stare into the mesmerizing sameness.

And so Anlyn Hooo—Drenard Princess, member of the Great Circle— kept her head down as she piloted the Bern craft through hyperspace. It had been two weeks to the day. Two weeks of exhausting one-hour shifts, causing her to develop a powerful antipathy to the sight of the relentless snow outside. She preferred to rest her chin on her chest and monitor beneath drooping eyelids their ship’s position within the vast invasion fleet, following everything from the instrument readouts.

Edison snored beside her in his gruff and intermittent way. The massive Glemot, her co-pilot and fiancé, was fast asleep with the radio mic clutched in his paws. Anlyn checked the ship’s clock, dreading the answer to her weary and eternal question: How much time left on my shift?

Forty minutes.

It filled Anlyn with guilt and dread. Dread for the perceived hours and days it would take for those forty minutes to tick down and guilt for knowing that Edison would have to take over for her once they did.

Another ship passed through the open rift ahead, and the fleet adjusted accordingly. Anlyn felt a rush of adrenaline as she leaned forward, gripped the control stick, and matched the precise movements of the Bern. It took every ounce of her will to fly like a fresh pilot, alert and ready, rather than the half-dead thing she had become. A thousand times over the past weeks, Anlyn had foreseen the end to hers and Edison’s endurance: There would be a wobble and a gradual falling out of formation. Barked orders full of suspicion would follow, and Edison’s sleep-deprived lies would not wash them away. The final stage would be missiles and plasma bolts to end their fitful ruse—

A loud bang in the rear of their ship interrupted Anlyn’s thoughts. Edison bolted upright, the radio coming to his mouth in reflex. He scanned the dash before looking to Anlyn in confusion.

“Diagnose!” he said in his native English.

Anlyn shook her head. “I don’t know,” she said. She tried to force the cobwebs aside and think clearly. “It sounded mechanical, but none of the gauges have so much as twitched.” She looked to the SADAR, but it was nearly useless in the driving snow. “The fleet is moving again. Maybe it was a collision?”

Edison began to rise from his seat to go inspect the cause of the noise, but Anlyn placed a hand on his chest and attempted to push him back.

“I can’t speak Bern,” she reminded him. She glanced at the mic in his hand. “Stay here in case the fleet calls. I’ll go see what it was.”

She unbuckled her harness while Edison yawned—his long furry arms running out of room for a decent stretch. She ducked under his elbow and padded out of the cockpit on wobbly legs, heading aft. In her sleepy pilot brain, she went over all the possible causes for the loud, metallic sound. A ceiling panel could’ve fallen loose and slammed into the decking. A storage cabinet could’ve vibrated off its rivets. One of the generators could’ve thrown a rod.

But then she heard something else, something easier to recognize. It was a thumping sound, rhythmic, just like the footfalls of someone running.

And it was getting louder.

•• 2 ••

Cole finished his second sweep of the port side, seeing nothing more than the messes he had left behind the first time. He reached the cockpit after Marx and helped the large Callite drag Bern bodies out of the way. It looked like the pilot and co-pilot had cut down several Bern in taking over control of the ship.

Despite the design of his Underground boots, made to grip through blood and ice, Cole found himself slipping and sliding as he drug a Bern’s torso out of the cockpit’s narrow hallway. There was a gruesome normalcy to the task, like arranging furniture, that nearly made Cole gag. He forced himself to not look the dead man in the eye as he added him to a pile Marx had already started. The Callite threw a plastic tarp over the figures while Cole looked for something to mop up the blood. There was no way they could work with such a thick pool of it right in the cockpit. He pulled a jacket off one of the Bern crewmen, looking away from the Human-like face as he did so. He threw the jacket down into the spilled gore and pushed it around with his boot, trying to mop a path through the mess.

“Ryke was right about the windshields,” Cole heard the navigator say. “They’re already darkened, so we won’t be needing our goggles.”

“Keep em around your necks anyway,” someone else in the cockpit barked.

A third voice burst out in a strange language, causing Cole to pause from his dirty work and scramble for his buckblade. The cadence and inflection of the words sounded similar to what several Bern crewmen had been shouting before Cole had cut them down.

“Shhh!” somebody hissed. “Complete silence!”

Cole left the soiled jacket wadded up against the bulkhead and stuck his head in the cockpit. He watched as Larken, the squad translator, leaned forward from one of the seats and spoke foreign words—the same type of words—into the mic. Everyone froze, anxious and tense.

When he stopped speaking, a voice came through the radio again. Larken held his eyes closed and turned to face the pilot. He nodded now and then as the rapid Bern continued.

“What was that about?” the pilot asked as soon as the voice fell silent.

“They want us to check for any problems. One of the other ships called something in, and now they won’t respond.”

“You want me to go check?” the navigator asked, jabbing a thumb over his shoulder.

“Moron,” the pilot said. “We’re the problem.”

“One of the other squads must be in trouble,” Cole said.

“That’s why we sent five groups,” the pilot muttered. He turned to the navigator. “Call HQ on the carrier frequency, but keep it short. Just give them our velocity and the coordinates for our cargo bay, one meter off the deck. Tell them we’re secure and can hold as much as they can send.”

The navigator nodded and pulled his long-wave radio from his pack.

The pilot looked over his shoulder. “Marx, you and Cole head back to the cargo bay and coordinate our arrivals. Let’s pack as much as we can into this puppy, just in case we’re the only ones who make it through to the other side.”

“Yes, sir,” Marx said from behind Cole. The Callite stomped aft through the thin skim of drying blood.

Cole took off after him, his thoughts divided between how well his squad had done on their portion of the raid—and on which of the other groups had run into trouble.

•• 1 ••

Penny raced through the ship’s corridors, the dying screams of the last Bern crewman echoing in her ears. She slowed to round a bend in the passageway, then found herself in the aftermost section, the rumble of powerful thrusters audible through the thick bulkhead.

The sound intensified as a door opened. A Bern engineer stepped out, his gray coveralls spotted with grease stains. Penny sliced him in half before he could even register her presence. She watched the two pieces of meat fall to the deck, strings of interior organs spilling out in a thick soup. She studied the odd arrangement, the fleshy interior, and felt more curiosity than horror.

A rhythmic clanging rang out over the roar from the open thruster room. Penny kicked the door shut to hear better. It was footsteps. Someone running. She prepared her blade just as Mortimor jogged around the corner and came to a panting stop.

“You okay?” he asked. He pulled his blood-specked hood back and ran his fingers through his graying hair.

Penny nodded and lowered her sword. “I think this is the last—”

Before she could finish the sentence, Penny flew into the air and slammed into the rear bulkhead. Mortimor followed, his limbs flying out for balance. Gravity returned, and they both fell to the deck. Penny felt her weight lessen again, like the ship was dropping altitude, but the grav panels should’ve more than compensated for any maneuvering. She looked across at Mortimor, her hands splayed wide and her fingers digging into the grating on the floor.

“The cockpit!” Mortimor yelled.

Penny pushed herself to her feet. The whine of the thrusters in the next room suddenly lowered in pitch—and then the engines began screaming higher and harder than before. Something was wrong. She took off, churning up the meters back to the cockpit, her legs hammering away at the artificial gravity, her mind willing it to last.