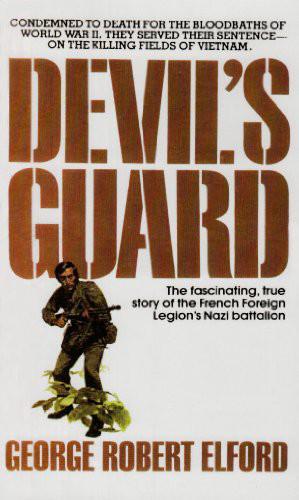

The personal account of a guerrilla fighter in the French Foreign Legion, reveals the Nazi Battalion’s inhumanities to Indochinese villagers.

WHAT THEY DID IN WORLD WAR II WAS HISTORY’S BLOODIEST NIGHTMARE.

The ashes of World War II were still cooling when France went to war in the jungles of Southeast Asia. In that struggle, its frontline troops were the misfits, criminals and mercenaries of the French Foreign Legion. And among that international army of the desperate and the damned, none were so bloodstained as the fugitive veterans of the German S.S.

WHAT THEY DID IN VIETNAM WAS ITS UGLIEST SECRET — UNTIL NOW.

Loathed by the French, feared and hated by the Vietnamese, the Germans fought not for patriotism or glory but because fighting for France was better than hanging from its gallows. Here now is the untold story of the killer elite whose discipline, ferocity and suicidal courage made them the weapon of last resort.

George Robert Elford

DEVIL’S GUARD

INTRODUCTION

Working in the Far East as a zoologist I met many interesting people and, occasionally, a few truly extraordinary individuals. One of them was the real author of this manuscript: Hans Josef Wagemueller, the one time SS Partisan-Jäger—guerrilla hunter—who later became an officer of the French Foreign Legion in Indochina, now known as Vietnam. We met in a bar in the capital city of a small Asian nation of which he is now a citizen. He was interested in my anesthetic rifle equipment, which I was using to immobilize wild animals for scientific research.

“I used to be a hunter myself,” he said to me with a smile I will never forget. “I was a Kopfjäger—a “head-hunter” as you would say in English. You hunt elephants, rhinos, tigers. I hunted the most agile of all beasts—man! You see, my adversaries were by no means any less ferocious than their counterparts in the animal world. My game could think, reason, and shoot back. The majority of them were what we now call the Vietcong. They posed as gallant freedom fighters, the redeemers of poor people. We used to call them “the mechanized hordes of a space-age Genghis Khan.”

If there was a spark of truth in the Hitlerian credo about the existence of superior and inferior races, we met the real subhumans in Indochina. They tortured and killed for the sheer pleasure of causing pain and seeing blood. They fought like a pack of rabid rats, and we treated them accordingly. We negotiated with none of them, and accepted no surrender by those who were guilty of the most horrible crimes that man or devil can conceive. We spoke to them in the only language they understood—the machine gun.”

The life story of Hans Josef Wagemueller is a long and unbroken record of perpetual fighting. He fought against the partisans in Russia during World War II; he spent over five years in French Indochina, fighting against what he described as “the same enemy wearing a different uniform.”

When that was over, he moved into a small Asian country to train its token, archaic army in the intricacies of modern warfare and the use of modern weapons. “I have managed to turn a horde of primitive, superstitious, and undisciplined warriors into a crack division of daring soldiers,” he stated with pride. “You could incorporate them in any European army without further drilling.”

The head of state where he now lives has granted him citizenship. The local university has bestowed upon him the title Honorary Professor of Military Sciences. He is now Hindu by religion and has a local name. At the age of sixty-four, he is still going strong. His day begins with rigorous physical exercises. Target shooting is still his favorite pastime, and his steely blue eyes are still deadly accurate when looking through the gunsight.

When the United States became entangled in the Vietnam conflict, Hans Josef Wagemueller offered his experience to the American High Command in a long letter that remained unanswered.

“I probably made a mistake by having written a somewhat haughty and in a way maybe a bit lecturing letter,” he said. “But our own long and unbroken record of victories against the same enemy in the same land was still fresh in my memory, and the unnecessary death of every American soldier, every debacle that could have been avoided, hurt me deeply. I could not think of the Vietnam war in any way except that it was my own war. Those GI’s scouted the same jungle trails where we had trekked for many years. Many of them had to die where we survived. Somehow it was an inner compulsion to regard them as comrades-in-arms. And you know what? I am not surprised that young Americans are tearing up their draft cards and refusing to go to Vietnam. To take young college boys out of their super civilized surroundings and cast them into the primitive jungles of Asia is nothing but murder. Sheer murder. Only experts, highly skilled and experienced antiguerrilla fighters, can survive in the jungles of Asia. It takes at least a year of constant fighting before a recruit turns into an expert.”

After that evening together—which left me shaken and sleepless for the rest of the night—I asked Wagemueller if he would tell me his entire story. He obliged by talking into the microphone of a tape recorder for eighteen consecutive days. I have merely altered some of his technical military phraseology for the sake of better understanding. This is a true document with nothing essentially changed except the names. Wagemueller obliged me to keep his true identity, as well as that of all the others, undisclosed.

“I am requesting this not because of my being a war criminal. I have told you the true story. I can give you my word of honor on it. I still consider myself a German officer and a German officer will keep his word of honor no matter what. But I have an eighty-seven-year-old mother whom I would never expose to endless inquiries by the authorities and by the press. And there are certain people mentioned in my story who are still living in my hometown near the Swiss frontier and who helped many other fugitive German officers to avoid prison and prosecution after the war. I do not know who the other fugitives may have been, but what I do know is that there were close to two thousand comrades in distress who left Germany the way I did in 1945. The escape route was extremely well organized and it is quite possible that some important Nazis used it too.

“Another important consideration is that I should not embarrass certain high officials of my adopted country who have been helping me ever since my arrival here. Besides,” he added with a smile, “I was not very popular with the Chinese People’s Army—and China is not very far from here.”

He wants his share of the author’s royalty to go to the widows and orphans of those Americans who fell in Vietnam. “I have all I need for the rest of my life. I want no money, only justice to German officers and soldiers who were correct to the core, yet had to share the disgrace of a few. And I want to show the enemy stripped of its mask of gallantry and heroic myth.”

I have refrained from adding any comment of my own. It is up to the reader to form his own judgment, as it is up to history to pass the final mandate upon him, his companions, and their deeds.

FOREWORD

I have seen many deadly landscapes, from the Pripet swamps in Russia to the jungles of Vietnam. Unfortunately most of what I saw was seen only through a gunsight, with no time to enjoy the scenery. I was a kopfjaeger—“headhunter,” as our comrades of the Wehrmacht used to call us. We were a special task force of the Waffen SS—the “fighting SS”—which had nothing to do with concentration camps, deportations, or the extermination of European Jewry. Personally I never believed that the Jews could or ever would become a menace to Germany and I hated no people, not even the enemy. I never believed in German domination of the world but I did believe that Germany needed lebensraum. It was also my conviction that Communism should be destroyed while still in its cradle. If my beliefs should be called “Nazism,” then I was indeed a Nazi and I still am.

During the Second World War my task was to frustrate guerrilla attacks and suppress insurgency in our vital rear areas and around communication centers, seldom farther than fifty miles from the front lines. Regardless of age or sex, captured guerrillas were, as a rule, executed. I was never interested in their race or religion and tolerated no outrage against prisoners. My orders were to hang them, but I permitted the brave ones to die a soldier’s death, facing the firing squad. During five long years we executed over one thousand guerrillas. If there were Jews among them, we shot them too—but without any religious prejudice.

I have not stayed away from Germany because of my crimes but because I have no desire to behold what they call Germany today—a land of bowing Jawohl Johanns who can only repeat “yes, sir” or “da, tovarich” in either American or Russian servitude. The present German Army is only a shadowy midget of its former self. The old “Wehrmacht needed neither foreign advisers nor protectors. It is a fact that we have lost two offensive wars, fighting alone against the World. But I doubt that the Wehrmacht would have lost a defensive war had the frontiers of the Fatherland been invaded from the outside.

Once our German engineers built the best fighting aircraft in the world, and I believe that we can still build the best if given a chance. Instead we must use Starfighters in which the young German airmen are obliged to fly kamikaze missions. About eighty of them have already crashed without having been shot at. Germany is obliged to purchase foreign rubbish; tanks, for instance, many of which are probably inferior to our wartime Tigers and Panthers. Our formidable NATO allies will not permit German industry to produce equipment for the army. Our best brains are siphoned away by foreign countries because our government will not pay them the wages they deserve. Should another war come, Germany will be expected to stand by her allies, who are, nevertheless, still scared of the Teutons, and any proposal for a German rearmament remains anathema for them. Our Western allies have yet to realize that the map of the world has changed. Now the nations of all continents may choose between only two camps. Any thought of neutrality between those two camps is nothing but self-delusion that will crumble under the first serious pressure from the outside.

Fortunately the East German regime fares no better. The Russians, too, would think twice before giving the People’s Army any sophisticated weapon. But the Volksarmee has an ideology to follow and it certainly does not have draft dodgers.

I spent five years in Indochina, fighting the same enemy that I had fought in Russia, wearing another uniform. I know well the marauders of Ho Chi Minh. We fought them and routed them a hundred times, in the mountains, in the jungles, in the swamps. We beat them at their own game. We never regarded the terrorists as demigods or specters who could not be destroyed. After our years in Russia we could put up with hardship and misery. When we arrived in Indochina we were not beginners.”

When we moved into Communist-dominated territories, there was soon peace. Sometimes it was the peace of the bayonet, sometimes the peace of a cemetery. But it was peace. Not even a lizard would dare to move. If history records any French victory in Indochina, it was won either by the French paratroops, who were magnificent fighters, or by us Germans.

The war in Indochina was not lost on the battlefield but in Paris. The Americans are losing the same war in Paris—right now. Paris and Geneva… the only battlefields where the Western world has suffered debacles, and where the Western world will always lose.

It is, of course, nonsense to say that the American Army cannot defeat the guerrillas in Vietnam by force of arms. After all the American fighting men defeated Japan. The jungles and swamps of Guadalcanal or Okinawa offered no easier going than, for instance, the Mekong delta. Besides, what army in military history was more effective in jungle fighting than the Imperial Japanese Army? But now American generals are compelled to fight world opinion instead of the Vietcong. History will only repeat itself. At the beginning of the Second World War the German generals were free to plan and conduct their own battles and they won every battle on every front. Then Hitler took command and everything was lost. When General MacArthur was permitted to act to the best of his abilities, the world saw a marvelous landing at Inchon and the North Korean rout. But when he had to obey orders coming from ten thousand miles away, American soldiers had to sacrifice their lives for no gains whatever.

C’est la guerre!

1. UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER

The news of the German capitulation reached us by radio deep in the Czechoslovakian mountains, east of Liberec. We had been up there for almost a month, holding an important pass, waiting for the Russians to come. But as the days went by, nothing disturbed our positions and even the local partisans refrained from engaging us in a major skirmish. Unusual stillness blanketed the peaks and the valleys—the sort of sullen tranquility that, instead of relaxing the mind, only charges it with tension. Strange as it may be, after five years of war and hundreds of engagements with the enemy, both regulars and insurgents, we were in no condition to bear the quiet of peace. Of all the natural human functions which we had once possessed we seemed to have retained only those that were important for our immediate survival: to eat, to sleep, to watch the woods—and to pull the trigger.

None of us doubted that the end was near. Berlin had fallen and Hitler was dead. Military communications had long since broken down, but we could still listen to the foreign broadcasts, including those of the victorious Allies. And we knew that our saga would not end with the capitulation of the Wehrmacht; that there would be no going home for the tired warriors of the vanquished army. We would not be demobilized but outlawed. The Allies had not fought only to win a military victory. Their main objective was revenge.

The last dispatch which we had received from Prague eight days before had ordered us to hold our positions until further orders—orders that never came. Small groups of haggard German soldiers came instead. Unshaven and hollow-eyed troops who had once belonged to every imaginable service in the Wehrmacht—the SS, the Luftwaffe, and the SD (Security Service). Among them were the surviving members of a decimated motorized infantry brigade, a Luftwaffe service group, a panzer squadron left with only two serviceable tanks; there were also five trucks of a one-time supply battalion and a platoon of field gendarmes. The remnants of an Alpenjaeger battalion had survived the retreat all the way from the Caucasus to end up with us, near Liberec. We were all waiting for a last sensible order, the order to evacuate Czechoslovakia and return into Germany. The order to cease hostilities came instead.

For us, deep in hostile territory, the news of the armistice sounded like a sentence of death. V/e had no one to surrender to except the Czech guerrillas or the militia, neither of which recognized military conventions or honor. Up to the very end we expected to be ordered back to Germany before the weapons were laid down. We could expect no quarter from the partisans—-we had killed too many of them. As a matter of fact we could expect no prisoner-of-war treatment from the Red Army either. The truck drivers of the supply battalion might be pardoned but not the Waffen SS, the archenemy. In a sense we felt betrayed. Had we known in advance that we v/ere to be abandoned to our fate, we would have withdrawn despite our orders to stay. We had taken more than a soldier’s share of the war and no one could have accused us of cowardice.

For five long years we had given up everything: our homes, our families, our work, our future. We thought of nothing but the Fatherland. Now the Fatherland was nothing but a cemetery. It was time to think of our own future and whether our beloved ones had survived the holocaust wrought by the Superfortresses during the last two years of the war.

Our headquarters had ordered us: “Stay where you are and hold the pass.”

Then our headquarters returned to Germany. Like the Roman sentry who had stood his guard while Vesuvius buried Pompeii, we too remained soldiers to the bitter end.

We had survived the greatest war in history, but if we were to survive peace, the most bloodthirsty peace in history, we had to reach the American lines two hundred miles away. Not because we thought much of American chivalry but at least Americans were Anglo-Saxons, civilized and Christian in their own way. Around us in the valley were only the Mongolian hordes, the Tatars of a mechanized Genghis Khan—Stalin. I had the notion that it was only a choice between being clubbed to death by cavemen or submitting to a more civilized way of execution.

To reach Bavaria and the American lines we had to cross the Soviet-controlled Elbe. We were still confident of our own strength. We had survived more hell than could possibly wait for us on the way home. German soldiers do not succumb easily. We could be defeated but never crushed.

All day long Captain Ruell of the artillery had been trying to reach the headquarters of Field Marshal Schoerner. No one acknowledged his signals but finally he did manage to contact General Headquarters at Flensburg. I was standing close to him and saw his face turn ashen. When he lowered his earphones he was shaking in every limb and could barely form his words as he spoke: “It’s the end… The Wehrmacht is surrendering on all fronts… Keitel has already signed the armistice… Unconditional surrender.”

He wiped his face and accepted the cigarette which I lighted for him. “The Fatherland is finished,” he muttered, staring into the distant valley with vacant eyes. “What now?” Suddenly it dawned on us why the Russians had refrained from forcing the pass. The Soviet commander had known that the war was about to end, and he did not feel like sacrificing his troops only minutes before twelve o’clock. But he as aware of our presence in the neighborhood. Within six hours after the official announcement of the German capitulation, Soviet PO-2’s appeared overhead. Circling our positions the planes dropped a multitude of leaflets announcing the armistice. We were requested to lay down our weapons and descend into the valley under a flag of truce. “German Officers and Soldiers,” the leaflets read, “if you obey the instructions of the Red Army commander you shall be well treated, you will receive food and medical care due to prisoners of war, according to the articles of the Geneva Convention. Destruction of war material and equipment is strictly prohibited. The local German Commander shall be responsible for the orderly surrender of his troops.”

Had our plight not been so bitterly serious we could have sneered at the Russians quoting the Geneva Convention, something the Kremlin had neither signed nor acknowledged. The Red Army could indeed promise us anything under the articles of the Convention; it was not bound by its clauses.

The following morning our sentries spotted a Soviet scout car as it labored uphill on the winding road to our positions. From its mudguard fluttered a large white flag of truce. I ordered my troopers to hold their fire, and called a platoon for lineup. Everyone was shaved and properly dressed. I wanted to receive the Soviet officers with due respect. I was astonished to see the car stop three hundred yards short of our first roadblock, and, instead of sending forward parliamentaries, the enemy began to deliver a message through loudspeakers.

“Officers and soldiers of the German Wehrmacht… The Soviet High Command knows that there are Nazi fanatics and war criminals among you who might try to prevent your accepting the terms of armistice and consequently your return home. Disarm the SS and SD criminals and hand them over to the Soviet authority. Officers and soldiers of the Wehrmacht… Disarm the SS and SD criminals. You will be generously rewarded and allowed to return home to your families.”

“The filthy liars!” Untersturmführer Eisner sneered, watching the Russian group through his binoculars. “They will be allowed to return home! That is a good joke.”

It was amusing to note how little the enemy knew the German soldier. After having fought us for so many” years, the Soviet High Command should have known better. Cowardice or treason was never the trade of the German soldier. Nor was naivete. They had called us “Fascist criminals” or “Nazi dogs” ever since “Operation Barbarossa.”

In the past they had made no distinction between the various services. Wehrmacht, SS, or Luftwaffe had always been the same to Stalin, yet now he was endeavoring to turn the Wehrmacht against the SS and vice versa.

The loudspeakers blared again. Eisner pulled himself to attention. “Herr Obersturmführer, I request permission to open warning fire.”

“No! Nothing of the sort, gentlemen,” Colonel Stein-metz, the commanding officer of the small motorized infantry group protested. “We shouldn’t fire at parliamentaries.”

“Parliamentaries, Herr Oberst?” Eisner exclaimed with a bitter smile. “They are sheltering behind the flag of truce to deliver Communist propaganda.”

“Even so,” the colonel insisted. “We may request them to withdraw but we should not open fire.”

Being an officer of the Wehrmacht, Colonel Steinmetz had no authority over the SS. He was, however, a meticulously pedantic officer and much our senior both in rank and age. I did not feel like entering into futile arguments, especially in front of the ranks. Trying to avoid the slightest offensive quality in my voice I reminded him that I was in charge of the pass and all the troops therein. Even so the colonel stiffened at my remark and said, “I am aware of your command. Herr Obersturmführer, and I hope you will handle the situation with the responsibility of a commander.”

The Russian loudspeakers kept blaring. Eisner shrugged and began to observe the enemy again. I exchanged glances with Erich Schulze and saw defiance in his eyes. Both men had been my comrades for many years. Bernard Eisner had been my right hand since 1942. He was a cool and hard fighter. Having been well-to-do landowners, Eisner’s father and elder brother had been beaten to death by a Communist mob during the short-lived “proletarian revolution” after the First World War. It was Bernard’s conviction that no Communist on earth should be left alive. Schulze, who had joined my battalion in 1943, was rather hotheaded but always polite and considerate.

A few steps from where we stood two young troopers sat behind a heavy machine gun, which they kept trained on the Soviet scout car. Their faces were tense but lacking emotion, as though they were statues or a part of the gun. Both were young, only nineteen years old. Drafted in 1944, they had not experienced the real trials of the war.

I asked for a loudspeaker and addressed the Russians: “This is the German commander speaking. We have not received an official confirmation of the armistice and we will hold our positions until such confirmation can be obtained. I request the Soviet commander to furnish an authentic document related to the question of armistice. I also request that, in the meantime, the Soviet propaganda unit refrain from using the flag of truce for communicating subversive propaganda. I request that the Soviet propaganda unit withdraw from our positions within five minutes. After five minutes I shall no longer consider them immune to hostilities.”

“German officers and soldiers… Disarm the SS and SD criminals and hand them over to the Soviet authority.

You shall be generously rewarded and allowed to return home.”

“I request that the Soviet propaganda unit refrain from using the flag of truce for communicating subversive propaganda,” I repeated. There was a pause; then the loudspeakers blared once more. “German officers and soldiers… Disarm the SS and SD criminals…”

I ordered, “Fire!” The scout car burst into flames, then exploded. When the smoke and dust settled we saw two Red army men scurrying down the road. “That should fix them for the time being,” Eisner remarked, lighting a cigarette. “Bullets are the only language they understand.”

An hour later a squadron of Stormoviks dived out of the clouds with the intention of strafing and bombing our positions. To reach us, however, the planes had to come in level between a cluster of high cliffs, then drop sharply over the small plateau which we occupied. The Russian pilots flew well, but they had bad luck. I had deployed eight 88’s and ten heavy MG’s to cover that narrow corridor and our gunners were experienced men. Within a few minutes five of the planes had been shot down. Trailing smoke two more had escaped toward the valley and a third one had banked straight into a three-hundred-foot rock and exploded, fuel, bombs, ammunition and all. At that point the four remaining planes had given up and departed without having fired a shot. We spotted two Soviet pilots parachuting downward. One of them hit a cliff, slipped his chute, and tumbled to his death at the bottom of a ravine. The other one, a young lieutenant, landed right on one of our trucks. He was made prisoner.

“Zdrastvuite, tovarich!” Captain Ruell, who spoke impeccable Russian, greeted our astonished visitor.

My men searched the pilot. I looked into his identification book but handed it back to him. And when Schulze gave me the officer’s Tokarev automatic, I only removed the bullets and returned his gun as well. He was so surprised at my unexpected behavior that his chin dropped. He tried to smile but he could not. He only managed to draw his lips in a paralytic grin.

“The war is over,” he muttered. “No more shooting,” he added after a moment, imitating the sound of a submachine gun. “No tatatata.”

His face showed so much terror that we could not help smiling. He must have been told that Germans were man-eaters.

“No more tatatata, eh?” Erich Schulze chuckled, mocking the Russian.

The pilot nodded quickly. “Da, da… No more war.”

Schulze poked him in the belly. “No more war but a minute before you wanted to bomb the daylight out of us here.”

“Ja, ja,” the Russian repeated, his eyes glued to Schulze’s SS lapel.

Erich poked him gently again, and the Russian paled.

“Leave him alone,” Captain Ruell interposed. “You are scaring the shit out of him.”

“Sure,” Eisner added, “and we don’t have many extra pants up here, Erich.”

The captain spoke to the pilot briefly and his presence seemed to lessen the Russian’s fear. “Don’t let the SS shoot me, officer,” he pleaded. “I have been flying for only eight months, and I want to go home to Mother.”

“We have been fighting for five years. Imagine how much we would like to return home,” Captain Ruell replied with a bitter smile.

“Don’t let the SS shoot me…”

“The SS won’t shoot you.”

Schulze offered the Russian a cigarette. “Here, smoke! It will do you good.”

“Thanks.”

The pilot grinned, taking the cigarette with shaking fingers.

Erich opened his canteen, gulped some rum, then wiped the canteen on his sleeve and offered it to the pilot. “Here, tovarich… Drink good SS vodka.”

Realizing that his life was not in danger the Russian relaxed.

“Our commander says that you don’t want to surrender,” he said, shifting his eyes from face to face as though seeking our approval for what he was saying. “You must surrender… There are two divisions in the valley; forty tanks and heavy artillery are expected to come in a day or two.”

“Tovarich, you have already told us enough for a court-martial,” Schulze exclaimed, slapping the pilot on the back.

“You shouldn’t tell the enemy what you have or don’t have.”

Captain Ruell interpreted for him.

“I only said that heavy artillery is on the way.”

“Who cares?” Eisner shrugged. “There is a mountain between your artillery and us.”

“The mountain will not help you.”

The Russian shook his head. He turned and pointed toward a ridge five miles to the southeast. “The artillery is going up there.”

“Nonsense!” I said. “There is no road.”

“There is a road,” Captain Ruell interposed, “right up to hill Five-O-Six. We had four Bofors there in early March.”

Looking at the map I realized that Captain Ruell was right and what the Russian pilot was saying had a ring of truth. Should the Soviet commander mount some heavy artillery on that hill, he could indeed shell our plateau by direct fire.

We gave the Russian a hearty meal and allowed him to leave. He was immensely happy and promised to do everything for us should we meet again after surrendering. “Food, vodka, cigarettes, Kamerad. My name is Fjodr Andrejevich. I will tell our commander that you are good soldiers and should be well treated.”

“Sure you will,” Eisner growled, watching the Russian leave. “You just tell your commander and you will be shot before the sun is down as a bloody Fascist yourself.”

The pilot walked away slowly, turning back every now and then as though still expecting a bullet in the back. Having passed our last roadblock it must have occurred to him that he was still alive and unhurt, and he began to race downhill as I had never seen a man run. Eisner was not very enthusiastic about the Russian’s departure.

“He saw everything we have up here,” he remarked with barely concealed disapproval in his voice.

“We had no choice but to let him go,” Colonel Steinmetz challenged him sharply. “The war is over, Herr Untersturmführer.”

“Not for me, Herr Oberst,” Eisner replied quietly. “For me the war will be over when I greet my wife and two sons for the first time since August 1943, and it isn’t over for the Russian either. He came here flying not the white flag but a fighter bomber.”

“I haven’t seen my family since June 1943,” the colonel remarked.

I drew Eisner aside. “You should not worry about the Ivan,” I told him with an air of confidence. “What can he tell? That we have men, weapons, tanks, and artillery? The more he tells the less eager they will be to come up here.”

I put an arm around his shoulder. “Bernard, we’ve killed so many Russians. We can surely afford to let one individual go.”

He grinned. “I have read somewhere what the American settlers used to say about the Indians, Hans. The only good Indian is a dead Indian. I think that is also true of the Bolsheviks.”

“Maybe the pilot was not a Bolshevik?”

“Maybe he wasn’t—yet. But if you ask me, Hans, I can tell you that anyone who is working for Stalin is game for me.”

He lit a cigarette, offered me one, then went on. “I know that we are defeated and that there will be no Fatherland to speak of for a long time to come. For all we know the Allies might break up the Reich into fifty little principalities, just as it was five hundred years ago. We scare them stiff, even without weapons, even in defeat. But I cannot suffer the thought of having been defeated by a rotten, primitive, lice-ridden Communist mob. I know that no conqueror in history was ever soft on the conquered enemy. We might survive the American and the British but never the Soviet. Stalin won’t be satisfied with what he may loot now. He will not only take his booty, but he will try to take our very souls, our thoughts, our national identity. I know them. I’ve been their prisoner. It was for only five days but even then they tried to turn me into a bloody traitor. The Russians are mind snatchers, Hans. They will not only rape our women, they will also turn them into Communists afterwards. Stalin knows how to do it and now he will have all the time on earth. He is going to increase the pressure inch by inch. I could gun down anyone who is helping Stalin.”

“You would have quite a few people to gun down, Bernard. Starting with the British and finishing with the Americans. They have not only helped Stalin, but also brought him back from his deathbed and made him a giant.”

“Stalin will be most obliged to his bourgeois allies,” Eisner sneered. “Just wait and see how Stalin will pay for the American convoys. Give him a couple of years. Mister Churchill and Mister Truman are going to enjoy a few sleepless nights for Mister Roosevelt’s folly.”

“That won’t help us much now, Bernard!”

“I guess not,” he agreed- After a brief pause he added, “If you decide to surrender, Hans, just let me have a gun and a couple of grenades. I will find my way home.”

“You won’t be alone.”

I gave him a reassuring tap. “I don’t feel like hanging in the main square of Liberec, either.”

“I don’t feel like submitting myself to what comes between the surrender and the hanging,” he added with a sarcastic chuckle.

Early in the afternoon the PO-2’s returned, but we did not fire on the flimsy canvas planes which carried no weapons. The Russians had sent us another load of leaflets, among them newspaper cuttings announcing the armistice, and photocopies of the protocol bearing the signature of General Field Marshal Keitel. Again we were requested to lay down our weapons and evacuate into the valley under the flag of truce.

“This is it!” Colonel Steinmetz spoke quietly as he crumpled the Soviet leaflet between his fingers. “This is it!” And as though providing an example, he unbuckled the belt which supported his holster, swung it once, and tossed the belt on a flat slab of stone. I expected nothing else from Colonel Steinmetz. He was a meticulously correct officer, a cavalier of the old school who would always keep to the letter of the service code. He could see no other solution but to comply with that last order of the German High Command, or what was left of it. Moving like automatons, his three hundred officers and men began to file past our sullen group, the troops casting their rifles and sidearms onto the mounting pile. But the artillery, the small panzer detachment, and the Alpenjaegers kept their weapons, and, with a skill born of habit, the SS took over the vacated positions.

“I am sorry,” Colonel Steinmetz said quietly, and I noticed that his eyes were filled. “I cannot do anything else.”

“There is no longer a high command, Herr Oberst, and the Fuehrer is dead. You are no longer bound by your oath of allegiance,” I reminded him.

He smiled tiredly. “If we wanted to disobey orders we should have done it a long time ago,” he said. “Right after Stalingrad. And not on the front but in Berlin.”

“You mean a successful twentieth of July, Herr Oberst?”

“No,” he shook his head. “I think what Stauffenberg did was the gravest act of cowardice. If he was so sure of doing the right thing, he should have stood up, pulled his gun, shot Hitler, and taken the consequences. But I don’t believe in murdering superior officers. The Fuehrer should have been declared unfit to lead the nation and, removed. Had Rommel or Guderian taken command of the Reich, we might have won—if not the war, at least an honorable peace.”

“It is either too late or still too early to discuss the Fuehrer’s leadership, don’t you think, Colonel Steinmetz?”

“You are right. Now all we can do is hoist the white flag.”

“We have no white flags, Herr Oberst,” Captain Ruell remarked with sarcasm. “White flags were never standard equipment in the Wehrmacht.”

The colonel nodded understandingly. “I know it is painful, Herr Hauptmann, but if we refuse to surrender, the Russians may treat us like we treated their guerrillas.”

“Are you expecting anything else from the Soviet, Herr Oberst?” Eisner asked.

“The war is over. There is no reason for more brutalities,” said the colonel. He turned toward me. “What do you intend to do?” I suggested that we should try to reach Bavaria, two hundred miles away, but the colonel only smiled at my idea. “By now, the Russian divisions are probably streaming toward the line of demarcation,” he said. “All the roads and bridges will be occupied by the Russians and precisely opposite the American lines you will find most of their troops. Stalin does not trust either Churchill or Truman. He has exterminated his own general staff. Do you think he would trust Eisenhower or Montgomery? The days of “our heroic Western Allies” are over for Stalin. In a few weeks” time the Western Allies will be called bourgeois, decadent, imperialist, and Stalin will deploy a million troops on the western frontiers of his conquest. Besides,” he added after a pause, “you should not expect much from the Americans, Herr Obersturmführer. I have heard many of their broadcasts.”

“So have we,” Eisner remarked.

“Then you should know about their intentions. A prisoner is always a prisoner. The conqueror is always right and the vanquished is always wrong!”

“We have no intention of surrendering, Herr Oberst, neither here nor in Bavaria,” I said softly.

“Are you planning to go on fighting?”

“If necessary… and until we arrive at some safe place.”

“Where, for instance?”

“Spain, South America… the devil knows.”

“You should not count on Franco. Franco is all alone now and they might put pressure on him soon. With Hitler and Mussolini dead, Stalin will never tolerate the existence of Franco, the last strong leader in western Europe. Stalin knows that he will be able to push around everyone but Franco. He will regard Spain as a potential birthplace, or rather a place of resurrection, for the Nazi phoenix. And to reach South America you will need good papers and plenty of money. But, to speak of more immediate problems, do you have enough food to reach Bavaria? I know you have enough weapons but your trip might take two months over the mountains, and I presume that is the way you intend to go. Man cannot live on bullets.”

“We have enough food for two weeks. One can always find something to eat. It is getting on to summer now,” I said. “There are villages and farms even in the mountains.”

He shook his head disapprovingly. “Are you planning to raid the farms and villages? Will you shoot people if they refuse to accommodate you?”

“If it is a matter of survival, Colonel Steinmetz…”

Eisner said before I could answer. He left the sentence unfinished for a moment, then added, “Have you ever seen a humane war?”

“It will no longer be an act of war but common banditry,” the colonel stated frankly. “Of course you still have the power to do it but you won’t be able to do it in silence. The Czechs will know about you. The Russians will know about you and your destination. The news of your coming might reach Bavaria before you do.”

“And we might have an American reception committee waiting for us at the frontier. This is what you wanted to say, Herr Oberst?” I interposed.

“Precisely!” said he. “And if up ’til now you haven’t committed something the Allies may call a war crime, you had better not furnish them with any evidence now!”

“Herr Oberst,” I spoke to him softly but firmly, “if we do reach Bavaria, nothing will stop us from getting further. Neither the Americans, nor the devil himself. We have given up many things a man would never willingly part with, and we are ready to give up more, even our lives. But not our right to return home. On that single item we will never compromise.”

“I wish I was as young as you are,” Colonel Steinmetz spoke resignedly. “But I am tired, Herr Obersturmführer… so very tired.”

Despite the old soldier’s pessimism I felt that somehow we had a fair chance of getting through, saving at least our bare lives. The prospect of being hanged by the guerrillas, or at best carted off to a Siberian death camp, did not appeal to me at all. The colonel might survive. He might even return home one day. The SS could entertain no illusions about the future. No Soviet commander would lift a finger to protect us. Should their Czech allies decide to get even with us, the Russians would quickly forget about their Geneva Convention pledge for humane treatment. For seven years the Czechs had been waiting for this day, and I could not blame them either. In 1944 alone we had killed over three thousand of their guerrillas.

“We should travel high up in the mountains, avoiding contact with the enemy. We have excellent maps of the areas involved, and if necessary we can fight our way through a Soviet brigade.”

“With a few hundred men?” the colonel asked skeptically.

“We have at least a hundred light machine guns, Colonel Steinmetz,” Eisner interposed. “We can put out so much fire that the Ivans will think a division is coming.”

“For how long?”

“Hell, we can play hide-and-seek in the woods until the Day of Judgment, Herr Oberst!” Schulze exulted. “We should at least try! To surrender here is sheer suicide. What have we got to lose? One may commit suicide at any time.”

Bernard Eisner and Captain Ruell were of the same opinion.

“We have mountains and woods all the way to Bavaria,” Ruell said. “I am quite sure that every one of us has been through similar trips a dozen times in the past.”

The colonel shook his head slowly. “Hiding in the forest? Sneaking in the night like a pack of wolves… stealing or robbing food at gunpoint, shooting people if they resist? No, gentlemen, I have been a soldier all my life and I shall finish it all like a soldier, obeying the orders of those who are entitled to give them.”

“The Soviet commander down in the valley, for instance?” Eisner remarked bitterly. The colonel frowned. “I am talking of General Field Marshal Keitel and Grand Admiral Doenitz,” he said.

“Keitel and Doenitz have no idea what a dreck we are in, Herr Oberst.”

“I guess not,” he agreed. “They have eighty million other Germans to worry about now. We are only a few hundred. We are not so important, gentlemen. We are neither heroes nor martyrs. We are only a part of the statistics. The death of a single individual may be very sad. When a hundred die they call it a tragedy, but when ten million perish, it is only statistics. I still believe in discipline, even in defeat. And we are defeated.”

“The only trouble is that I still cannot feel that I am licked,” Schulze remarked with a grin, tapping the stock of his machine gun. “Not while I still have this thing. But I would like to see the Ivan who comes to tell me all about it.”

“Shut up, Erich!” I snapped curtly and he froze with a brisk “Jawohl.”

“This isn’t the right time for wisecracking!” I turned to the colonel. “Herr Oberst, I am convinced that you will have a better chance if you surrender to the Americans.”

“I have already advised you not to expect too much from the Americans, Herr Obersturmführer. All that is going to happen from now on was agreed upon by the victors a long time ago. But I concede,” he added with a smile, “That an American jail might be somewhat more civilized than those of Stalin’s. Stalin would kill a million Germans cheerfully. The Americans will meticulously prove that they are doing the just and legal thing. On doomsday morning they will give you a nice breakfast, a shave, a bath, and should it be your last wish, they might give you a perfumed pink rope to hang on. But the end will be the same.”

I spoke to the rest of the troopers, telling the men frankly that Colonel Steinmetz’s decision was the only correct one, as far as the military code goes. But the German Army had ceased to exist and therefore I no longer considered them my subordinates but only my comrades in peril who had the right to speak for themselves. As for myself, I stated, I would leave for Bavaria! The artillery platoons, the panzer crew, the Alpenjaegers decided to follow the SS rather than surrender. “You might be a bunch of sons of bitches,” Captain Ruell said smiling, “but you seldom fail. I am with you!” The motorized infantry and the supply group were for Colonel Steinmetz.

The colonel shook hands with us and I saw anguish in his face as he spoke in a choked voice. “I can understand you. It is going to be hard on the SS. The victors have already decided that you are nothing but killers, including your truck drivers and mess cooks. I wish you a safe arrival, but be prudent and do not make it harder on yourself than it already is, Herr Obersturmführer.”

With a gently ironic smile he handed me his golden cigarette case, his watch, and a letter. “Take care of these for me,” he asked quietly. “Give them to my wife—if she is still alive and if you can ever find her.”

“I will do it, Herr Oberst.”

His officers and the men followed the colonel’s example and began to distribute their valuables among those who were to stay. “The Ivans would take everything anyway,” some of them remarked with a shrug. In exchange we gave them our spare shirts and underwear, some food, cigarettes, and most of our medical supplies. Then Colonel Steinmetz assembled his troops. We saluted each other and they departed.

We could hear them for a long time as they marched down the winding road singing: the colonel, six officers and NCO’s under an improvised flag of truce, a bed-sheet. Behind them two hundred and seventy men. Beaten but not broken. The men were singing.

Two miles down the road, around a lonely farmhouse at watch were the Russians and a battalion of militia with six tanks and a dozen howitzers. In the valley near the village we could observe more Red army troops.

The beloved old tunes began to fade in the distant valley where the road turned into the woods as it followed the -course of a small creek. The singing was abruptly drowned in the sharp staccato of a dozen machine guns.

Explosions in rapid succession shook the cliffs, echoing and reechoing between the peaks, and we saw fire and smoke rising beyond the bend. It lasted for less than five minutes. The howitzers and machine guns fell silent. We heard the sporadic reports of rifles, then everything was still.

Standing on a boulder, overlooking the valley, Captain Ruell lowered his field glasses and slowly raised his hand for a salute. Tears were flowing freely from his eyes, down his cheeks and onto his Iron Cross. I saw Schulze bowing his head, covering his face in his hands. Only Eisner stood erect, staring into the valley, his face like that of a bronze statue. My own vision blurred. My stomach knotted. I turned toward my men wanting to say something but my words would not form. I felt an attack of nausea. But Eisner spoke for me.

“There is the Soviet truce for you, men. I know easier ways to commit hara-kiri!” Three PO-2’s rose from the fields and came droning over the hills. We dispersed, taking cover, and resolved not to reveal ourselves no matter what the enemy might do. Flying a slow merry-go-round, the flimsy planes began to circle the pass and came in low over the trees. Working the dials of our wireless. Captain Ruell quickly tuned in on the Russian wavelength. He translated for us the amusing conversation between the squadron leader and a command post somewhere in the valley.

“Igor, Igor… Here’s Znamia… ponemaies? There are no more Germans up here,” the pilot reported. “You got them all!”

“Znamia, Znamia! None of the ones here belonged to the SS. We examined all the bodies. Fjodr Andrejevich says the SS Commander and his two officers are not among the dead! Znamia, Znamia!… Take another look!” Fjodr Andrejevich, the Russian pilot whom we permitted to leave. Cigarettes, food, vodka. Eisner must have read my thoughts, for he remarked quietly, “What did I tell you, Hans?”

“The positions are empty!” the pilot reported. “I can see the gun emplacements and two tanks. Znamia, Znamia! If there were more troops here they must have withdrawn into the woods.”

“Igor! Igor! Try to locate them… Ponemaies?” Fifteen minutes later the PO-2’s left and soon afterwards we spotted Soviet infantry moving up the road, two companies with three tanks to lead the way. Their progress was slow, for a dozen yards ahead of the tanks a group of demolition men moved on foot searching for mines. We allowed them to proceed up to the fifth bend below the pass where the road narrowed to traverse a small bridge between the rising cliffs. The demolition squad spent over an hour looking for mines or hidden electric wires around the place but neither the bridge nor the road around it had been mined. Our engineers had had a better idea. They had enlarged a natural cave on the precipitous slope and stuffed nearly two tons of high explosives in the crevasse.

Observing the enemy through his binoculars, Bernard Eisner slowly raised his hand. A few yards from where he stood a young trooper sat, his hand gripping the plunger of the electric detonator, his eyes fixed on Eisner’s hand. From down below came coarse Russian yells. The leading tank lurched forward. The enemy was moving across the bridge.

Eisner’s hand came down.

“Los!” There was an instant of total silence, as though the charge had misfired, then earth began to rumble. The rocks seemed to rise; stone and wood exploded from a billowing mass of flames and gray smoke. The tanks stopped. The infantry scattered, taking shelter—or what they thought was shelter. High above the road a cluster of cliffs tilted, hung at a crazy angle for a second, then began to tumble down. A cascade of earth, stone, and shredded pine roared from above to carry tanks, cars, and troops into the abyss below. One car and some fifty Red army men escaped the landslide and now clung to a short stretch of road that had turned into a flat, cover-less platform, a jutting precipice with no way to escape except by parachutes. We waited until the smoke and the dust settled, then opened up on the survivors with two 88’s. Direct fire with fragmentation shells, at three hundred yards. Only eight shells were fired. There were no survivors.

“I guess this is the end of World War Two,” Erich Schulze remarked when our guns fell silent.

“Sure!” said Eisner pointing toward the debris down below. “Down there are the first casualties of World War Three!” We stripped off our rank badges, army insignias and emblems; tore up our identity papers and pay books; burned everything including our letters from home. The Panther tanks and the guns went over the precipice. They were faithful companions and they had served us well. None of them should fall into enemy hands.

Ammunition for the rifles, machine guns, and submachine guns had been distributed equally among the men. We had more than enough bullets and grenades. Each man could carry five spare mags and a hundred loose bullets along with six grenades. Our supply of cheese, bacon, margarine, and other food stores had been likewise distributed. Water was no problem. There were plenty of creeks and streams in the mountains.

We were about three miles away when the Stormoviks came buzzing over the plateau. This time they could fly the corridor unpunished. The planes bombed and gunned our vacant positions for an hour without a break. When some of them departed, others came, and their uncontested attack was delivered with true Communist zeal and determination. The action would surely be remembered by Soviet war historians as a great Russian victory.

Seven weeks of hard trekking followed. We kept in the mountains, moving mainly at night, resting in remote ravines or in caves when we came upon some large enough to accommodate us. Only in the caves could we light small fires to boil coffee or to warm up our canned meat and vegetables. There was no need to warn the men about eating sparingly. Our self-imposed ration was one meal per day.

Every day we spotted swarms of PO-2’s as they flew reconnaissance over the woods, sometimes passing overhead at treetop level. Fortunately we could always hear them coming from miles away and had time to scatter and camouflage. We strapped green twigs around ourselves and onto our helmets and we looked more like moving bushes than men. When a trooper froze, no one could spot him from twenty yards.

After about a week the planes stopped worrying us.

The Russians had given up the futile idea of detecting us from the air. Instead they endeavored to block every bridge and every pass in our way, compelling us to choose the most impossible trails for our grueling journey. When we could cover five miles in one night, we considered it good going. It was a trying cat-and-mouse game. Death was away only in time but never in measurable distance.

The enemy had never really known where we were and with the element of surprise preserved, we were strong enough to challenge a battalion of Russians. We could have pierced their roadblocks but the action would have given away our presence in a specific area and also our direction. By avoiding contact we kept the Russian commander in suspense. He could only guess which part of the map we were heading for. We wanted to preserve the element of surprise for the most perilous part of our trip: the crossing of the Elbe. Therefore I decided to bypass the enemy roadblocks and stick to the paths of the mountain goats. Erich Schulze, who was born and had grown up in the Alps, and some Austrian Alpine Rangers were of immense help to us.

In a small clearing, not very far from our trail, we came upon a dilapidated hunting lodge. Eisner spotted two Red army trucks parked under the trees—a most unwelcome sight. A pair of CMC’s could transport eighty men, and there was no way of bypassing the place except by making a twenty-mile detour. I decided to wait and see whether it was only a coincidence or a trap in the making. Then suddenly we heard the thud of axes and trees falling. The enemy was only cutting wood! We wanted to lie low until the Russians departed but fate decided otherwise. Escorted by a dozen Red army men, a small group of German prisoners emerged from the woods. Pushing and pulling at the heavy logs, the men tried to lift their burden onto the trucks. As the prisoners strained the Russians amused themselves with filthy oaths and laughter. Some of them were kicking the men as they struggled past their grinning guards.

Schulze suddenly swore, “Gottverdammte noch’mal… look over there!” He exclaimed and handed me his binoculars. “They are officers!” I could distinguish two officers among the working prisoners. They were the ones the Russians seemed to abuse the most.

“The taller one is a captain,” Eisner announced. “The other one I can’t tell.”

“What shall we do about the poor devils?” Schulze queried. “We cannot sit here and look on.”

I glanced at my men, deployed along the forest’s edge. Filthy, unshaven, and worn as they were, I could see on their faces that they would have resented inactivity. “I am all for freeing them,” I said briskly, answering their silent question. “But if we still want to reach Bavaria, we should stage a pretty good diversion afterwards.”

For some days we had been moving northwest, making a beeline for a small German town, Sebnitz, where we hoped our people could help us< in our trip across the Elbe. We could not liberate the prisoners without killing the Russians and consequently revealing our presence to the enemy, the very thing I was trying to avoid all the way. A line drawn on the map between the pass which we had evacuated and the small clearing down below would inevitably point at the border near Sebnitz. I turned the problem over and over in my mind but it seemed more hopeless at every new angle.

Captain Ruell found the only feasible solution.

“We wanted to move toward Sebnitz,” he began excitedly, motioning us to have a look at the map. “Having hit the Russians here, we will probably have all night before the enemy sends someone up to investigate. We are about… here!” He placed his finger on the map, then looked up. “After liberating the prisoners we should turn south. Away from Sebnitz and the German frontier. Here is a small village. We could make it by midnight. We need some civilian clothes anyway. I don’t think our folks at home will have many clothes left. A quick raid on the village might confuse the Russians, especially if we grab every Czech identity paper we come across.”

“Czech papers!” Schulze exclaimed.

“What for?” Ruell grinned. “The Russians might conclude that we are heading inland, toward Austria. Otherwise why should we collect Czech papers?”

“I think it is a good idea, Herr Hauptmann,” a young lieutenant of the Austrian Alpenjaegers remarked cheerfully. “Austria is precisely the place we would like to” go. After the raid we might as well keep going south.”

“And run into a Soviet blocking party,” Eisner grunted.

“You had better stick with us, taking the longer way but arriving safely.”

“After the raid on the village we should double back toward the north and cross the border at Sebnitz,” Captain Ruell concluded.

“So be it!” Eisner stated and I agreed. Captain Ruell’s plan seemed as feasible as any we might conceive.

By five o’clock in the afternoon both trucks were loaded and the prisoners had been lined up for head count. There were twenty-three of them, escorted by twelve Russians. Schulze deployed three sharpshooters for each Red army man. “Drop them with a single bullet, otherwise some of the prisoners may get hurt.”

“Don’t worry,” one of the troopers remarked. “At two hundred yards we could hit a field mouse between the eyes.”

Schulze waited until the prisoners had climbed aboard the trucks. Standing in a small group the Russians watched them with their submachine guns ready.

“Fire!” said Schulze.

Thirty-six rifles fired a single volley. The bewildered prisoners threw themselves flat thinking that they were about to be killed. But our sharpshooters had aimed well. There was no return fire.

Our liberated comrades, as we soon learned, had been captured five days before the capitulation. The majority were officers. The captain, whose rank Eisner had recognized, was the former commanding officer of a signal battalion. He had naively believed that the Soviet commander would react chivalrously to his protest against compelling captive officers to remove roadblocks, fill antitank ditches, and perform other manual labor. The Soviet officer in charge, whose name Captain Waller never learned, had been quite drunk at the time, and having booted the “Fascist dogs” from his presence, he had ordered his troops to strip the “Gerrnanski” officers of their rank badges and insignias. Then roaring with drunken laughter he yelled: “Now you are no longer officers but ordinary ranks, …tvoy maty!” Captain Waller and Lieutenant Mayer were, however, permitted to retain their badges “To serve as an example” of what happens to complaining Fascist officers. “Now you go and cut wood, we need telephone poles.”

The Soviet officer swore. “You destroyed all the telephone poles… Now you are going to make new ones from here to Moscow.”

“You are lucky, Herr Hauptmann, that we came by here,” I said after our mutual introduction.

“You were more lucky that you could come by here at all,” he replied with a smile. “There’s no prisoner-of-war treatment for the SS, Herr Obersturmführer. I saw with my own eyes how the Russkis lined up and machine-gunned four hundred of your men into the Vistula.”

“They did that, eh?” Eisner grunted.

“Not the officers, mind you,” the captain added. “The officers are to be tried and hanged. It was all agreed upon between the Americans and Stalin.”

He uttered a short sardonical snort. “And that will be about the only Soviet-American agreement Stalin will keep! You had better watch out.”

“They won’t get us, Herr Hauptmann… at least not alive,” I stated, more resolved than ever to reach Bavaria. “Not me, that’s sure!” Schulze nodded, lifting his gun. “First they’ll have to take my toy away.”

“I expected nothing else,” Eisner fumed. “Now comes the great carnage… the revenge, gentlemen. There is going to be such a bloodbath in the Fatherland that all the SS ever did will look like a solemn church ceremony in comparison…”

“You may thank Himmler,” Waller said. “To kill the Jews was a great folly, my friends. He could have gotten away with anything but the Jews… The Jews are a world power, but not those wretched bastards whom Himmler was busy exterminating around the clock. These had done nothing and would never have done anything against the Reich. Nevertheless their ghosts are returning now, many of them wearing the conqueror’s uniform or the judge’s stola.”

“But what have we got to do with the whole bloody affair?” Schulze cried. “I was hunting partisans in the Gottverdammte Russian swamps and in the forests of Belgorod. They should hang the “Einsatzkommandos” or the Gestapo. It was their lousy job to kill Jews, not mine. Are we responsible for what those loafers did?”

“Don’t ask me, ask Stalin!”

“What does Stalin care about the Jews? He always regarded them as rotten capitalists. Most of the Ukrainian Jews were rounded up and executed by the Ukraine Militia.”

“What the hell are you arguing about!” Eisner snapped. “Himmler did kill the Jews, didn’t he? Now the world needs a scapegoat and it is the SS. Whether we pulled the trigger or just threw a ring about a village while the militia or the Gestapo rounded them up, it is one and the same thing for them. It was all because of the SS. We murdered everybody in sight, looted the corpses, and are now returning home loaded with stolen Jewish gold. We are the Scourge of God, the Devil Incarnate, the Teutons. They are murdering right now a million German prisoners in Siberia, maybe not by shooting—Stalin simply starves them to death. But is there any difference? All right… we gunned down a hundred hostages. They take a group of army officers from a prison camp, give them a mock trial, then hang them. It is one and the same treatment as far as I am concerned. I know that the SS destroyed Lidice. I have not been there, but if they did it—they had a reason. Why did the SS level that particular place? Why not the other ten thousand? Maybe it was because of the assassination of Heydrich, maybe it wasn’t, but there must have been a reason for it. They say the killers of Heydrich were Czech commandos from England, who dropped by chutes. Why did they go hide in Lidice? They should have stood up, fought, and gone down fighting—the brave paratroopers. No one would have associated them with the Czechs in Lidice. And what if the SS destroyed Lidice? Was it an overkill? How about Hamburg which the Allied bombers demolished, killing eighty thousand civilians in a couple of hours? How about Dresden and the hundred thousand civilian dead there? Just before the war’s end… Because their execution was done by bombs and not by machine guns should we call the Allies saints? Goddamit all,” he swore, wiping the sweat from his forehead, “all that kept us alive was the thought of surviving and returning home. If we still have homes to return to,” he went on. “Now everyone is telling us that we are going to hang. It is enough to drive you mad.”

“I am sorry,” Captain Waller said apologetically. “I did not want to upset you. Especially not after what you did for us. But I thought you had better know the truth instead of falling into a trap at home.”

“Just let them come and try to trap me,” Eisner fumed.

“I haven’t killed an American yet but I don’t think they are tougher than the Ivans—and I sure as hell killed a lot of the Ivans.”

“That’s enough for now!” I interposed authoritatively. “We have more urgent things to do than talk about postwar politics. How about moving on?”

“A good idea,” Captain Ruell agreed. “But before we leave let me booby-trap those CMC’s. It may help the Ivans to get downhill the shorter way.”

The troops laughed.

I knew their nerves were strained to the breaking point and each individual was a potential time bomb that might explode at any moment. My men were not killers at large, yet they already felt hunted, outlawed. They were brave soldiers bled white defending the Fatherland. The majority of them had been called up to the SS just like others had been called up to the various other services and put into uniforms. We were Nazis, to be sure, but who was not a Nazi in Hitler’s Third Reich? No one could hold any position in the Reich without becoming a Nazi. And if someone held any position in the Reich, his son volunteered for the SS—the “Elite Guard.”

Others volunteered because it was known to be an honor to serve in the SS. Besides, the uniforms were better, the food, the pay, and the treatment were better, leaves were more frequent. But no one had volunteered because he was told, “Join the SS and you- may kill Jews, or guard concentration camps.”

I would never deny that the SS was probably the most brutal fighting force ever conceived in the history of warfare. We were tough, maybe even fanatics. We were scared of nothing and no one. We were brought up to be brave. Our brutality was only iron discipline and an uncompromising belief in the Fatherland.

We had been taught and drilled to execute orders and had I been given the order to shoot Jews, gypsies, or prisoners of war, I would have executed that order just as I would have shot deer if ordered to do so. If that is a crime, they should hang every soldier in the world who wouldn’t pull his gun and shoot his superior officer through the head whenever he feels like disobeying an order. But my orders were to insure the safety of supply trains, to keep a forest around a vital bridge free from enemy infiltrators, or to track down partisans after an attack against a garrison. And that is exactly what I did! When I was ordered to take hostages, I took hostages, ten of whom were to be shot for every German soldier murdered by the guerrillas. When the guerrillas stabbed a German sentry in the back or threw a grenade into a staff car, a given number of hostages were executed. Their names had been made known to the population in advance. The partisans had always known that if they committed murder, we would retaliate.

The partisans would never tell a German soldier in advance that he was going to be killed. We did tell the guerrillas that if they killed a German soldier, Pjotr or Andrei would die! We gave them a chance, but they gave us none. Who was then the more guilty? Who did actually kill those hostages? Were the partisans innocent? They were as innocent as the lever of a guillotine. The lever does not kill. It only releases the blade! As soon as darkness fell, we moved on to execute Captain Ruell’s plan. We found a fairly wide dirt road that ran through the forest and, following a small advance guard, made good progress. Having arrived at the village about midnight we quickly deployed along the forest line, and I sent out a reconnaissance party with Schulze in charge. Schulze reported that there were no Soviet troops in the vicinity, only a group of Czech militia billeting in the ancient stone mansion of the local fire service. A captured Wehrmacht troop carrier stood in the archway but he saw no sentries and the place looked ripe for the taking. I selected ninety men to form three groups with Schulze, Eisner, and myself in command. The rest of the troops were to stay behind under the command of Captain Ruell. I told him that should any trouble develop he was not to interfere but should move northward according to our original plan.

covington Skirting the fields we moved into the village with so many dogs barking that they should have wakened the dead. “Don’t shoot except in the utmost emergency,” I told my men. “If you have to kill, use your bayonets. And if you must use your bayonets, don’t miss!”

“And if you see a window lit up, occupy the house!” Eisner added. “Seize everyone you find awake.”

To my great relief I discovered that the battle of Stalingrad would not have disturbed the militiamen whom we found all boozed up and sleeping it off happily on a dozen bare mattresses strewn about the wooden floor. “They haven’t got a worry on earth,” a young trooper beside me remarked as we quietly removed the militia’s weapons. “I sure wouldn’t mind being one of them. Boy, to be able to sleep like that.”

With the militiamen disarmed, the occupation of the village was only a matter of routine. My troops did not wait for instructions. They knew how to go about their business swiftly and with the skill of veterans. One detachment cut the telephone wires; two platoons left to cover the roads with MG’s; four men seized the belfry—an important precautionary measure for a church bell can be a very effective instrument if someone wants to raise the country for miles around. The wires of the air-raid sirens in front of the church were also cut.

Breaking up into groups of five men each we searched every house, confiscated civilian clothes, food, and personal papers and caused great consternation among the people. Some of them spoke German and were told we were Austrians on the way home, terribly sorry for the inconvenience but we needed their papers to survive the trip across Czechoslovakia. I knew that the nearest Soviet commander would be informed before dawn.

At last on German soil—at the Elbe but still on the wrong side. A battered old farmhouse stood on the edge of the woods with the burned shell of a Tiger visible among the ruins of a barn. Children were playing around the dead tank and smoke rose from the chimney. We kept the place under observation for several hours but spotted no Russians. Schulze decided to visit the farm at dusk. He returned with the farmer, Hans Schroll, a war cripple; a short, lean, embittered man in his early fifties hobbling on a pair of crutches.

“I shall try to help you,” he said, his face showing great concern. “But keep in the woods, for heaven’s sake. The Russkis are visiting us every day and one never knows when they might show up.”

“Life must be hard on you people,” Captain Ruell remarked sympathetically.

“Hard?” Schroll exclaimed with a short laugh. “Life here is nothing but assault, robbery, rape, and murder. I am the only man here for miles around. A half of a man,” he added bitterly.

“No, Herr Schroll,” Schulze shook his head, placing a hand gently on the man’s stump. “I think you are more than a man.”

“The Russkis herded away the entire male population,” Schroll went on. “They wouldn’t take me because of my leg. Nowadays you may call yourself lucky for having lost a leg and a female is safe only if she is seven months pregnant or seven years old.”

He sat with us for a while and from his embittered words we could form our first impression of our tarnished Fatherland. A Wehrmacht battalion was still fighting on a ridge half a mile away when the invaders had raped Schroll wife for the first time.

“One of them held a gun to my head,” the farmer said. “He threatened to shoot me if I moved. I couldn’t have moved much even without a gun at my head, could I? They were the front-line mob. Finally a major came yelling, trying to send the bastards out to fight. Do you know what happened to the major? They just grabbed him, took his pistol, and kicked him in the ass… kicked him right through the door…”

“How is it now?” I asked wearily.

“Na ja.”

He smiled resignedly. “The occupation troops are more polite. They are taking me and the children out of the room when they come to visit my wife.”

“Don’t say—”

“Jawohl, Kameraden. The German homes have become Red army whorehouses. But we should not condemn our wives and daughters. It is all our fault. We should have fought better. Fought like the Japanese with their suicide pilots and human torpedoes. We did not kill enough Russians.”

Schroll told us about the pontoon bridge at Pirna. Four T-34’s and several machine gun emplacements covered its approaches. “No Germans are allowed to cross the bridge without a special pass,” Schroll said. “You will never make it across there, but I can give you a boat.”

The boat was a leaky one and could carry only eight men at the most. We had to wait in the forest until the farmer had managed to patch it up. He left it at a prearranged place, driven ashore and camouflaged under the riverside shrubs. In it we found five loaves of dark bread, a sack of homemade biscuits, and two bottles of schnapps. There was also a note: Glueck auf!—Good Luck! Only a thin slice of bread and a small gulp of brandy for each man but it had been our first slice of bread for weeks and the brandy felt good. So did the small note of Hans Schroll—a great man in a great desert.

Only the clothes and the weapons were ferried across the river. The men had to swim as it would have taken too long, making it very risky. Nine of them never made it.

We pushed on toward the American zone. Four times we ran into Soviet patrols or Czech militia. We had to kill them in order to survive. The enemy troops were getting thicker every day, but the closer we came to Bavaria the more resolved we became to arrive there. We no longer cared to bypass the roadblocks or the enemy camps but attacked them, pouring lead as if we had an inexhaustible supply of ammunition. We were only forty-two men when we finally reached Bavaria at Wunsiedel. Three hundred and seventeen of our comrades had fallen so that we might arrive home.

Three miles from the border we encountered our first American patrol: a jeepload of young men led by a lieutenant. Clean, neatly dressed, and obviously well fed, they were sitting around the jeep with a mounted MG having dinner. Dinner with a record player in the grass blaring the “Stuka Lied,” the lively march of the German dive bombers.

We had the Americans like sitting ducks, but I saw no reason for killing them the way we had killed every Russian who blocked our way. I decided to pay them a visit, alone and unarmed.

Leaving Eisner, Schulze, and an NCO to watch the development, I left the shrubbery and walked up to the group. The soldiers stared at me with astonishment and reached for their guns. The lieutenant turned off the record player. He was a handsome young man of about thirty, tall and blond, just like some of us Teutons. He wore sunglasses which he removed to have a better look at me.

“I see you are having quite a picnic here, Lieutenant,” I spoke to him nonchalantly, gesturing toward their rifles that almost poked me in the belly. “You don’t want to shoot me, do you? The war is over.”

“Who the hell are you?” he blurted out glancing at his men, then back toward me. “What are you doing here?” I thought God bless my mother who had always insisted that I should learn English.

“What could a German do in his own country?” I asked him in return. “I am on my way home.”

“Who are you?”

“Only a German officer. Coming home from far away.”

“How come you speak English so well?”

“We are quite civilized people, Lieutenant. As you see, some of us can even speak English.”

I noticed that they were completely taken aback by my sudden appearance and for some time the officer seemed at loss as to what to say or do.

“Are you carrying any weapon?” he asked finally.

“Only a pocketknife.”

“Hand it over!” he ordered me briskly. I knew he said that only to say something. I handed him my knife and he motioned his men to frisk me. The result set him at ease. He offered me a cigarette, lighted one for himself, then taking a notebook from the jeep he began to rattle off a number of questions.

“Your name, rank, and unit?”

“Hans Josef Wagemueller,” I obliged. “Obersturmführer, twenty-first special partisanjaeger commando.”

“What’s that?” a freckled, lanky soldier interposed.

“Guerrilla hunter,” the lieutenant explained and I bowed slightly. “That’s right.”

“Your last combat station?”

“Liberec, Czechoslovakia.”

“Have you killed any Americans?” a squat little corporal cut in.

I smiled. “If there were any American troops serving in the Red army, then I sure as hell did.”

The lieutenant made a quick, impatient gesture. “He said he was in Czechoslovakia,” he said to the corporal.

“Wehrmacht or the SS?” he now demanded to know. I could barely conceal my amusement. Only the SS had Obersturmführers. The Wehrmacht had lieutenants. I shrugged.

“Wehrmacht, SS, Luftwaffe—what’s the difference?”

“There’s a helluva difference, buddy,” he snapped. “The Wehrmacht and the Luftwaffe go home but we hang them SS cutthroats good and high.”

He extended his hand. “Show me your pay book.”

“I haven’t got any.”

“How come?”

“Well, I just figured that our paymaster’s office might be closed for a while, so I threw my pay book away.”

He frowned. “You like jokes, don’t you?” he remarked curtly and turned to the squat little corporal who wore a pair of horn-rimmed glasses. “Joe, you had better call headquarters.”

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you, Lieutenant,” I suggested mildly and lifted a protesting hand toward their guns, which were coming up once more. “Please do not threaten me. At this very moment there are at least a dozen rifles pointing at you. My men are expert marksmen and they are a bit nervous. I don’t want to see you killed—unless in self-defense.”

The soldiers paled visibly. The lieutenant ran his tongue over his lips but his confusion did not last long. My troops began to emerge from the woods with their guns providing the necessary dramatic undertone. Their chins dropped, then their weapons. The lieutenant began to unbuckle his holster but I stopped him.

“Oh, never mind your gun, Lieutenant. We don’t want to shoot at each other. The war is over.”

We took them, jeep, guns, and record player back into the woods. “Nicht schiessen, Kamerad,” squat little Joe muttered in broken German. “Don’t shoot.”

Somewhat bitterly I acknowledged that even the SS cutthroats could quickly turn into comrades when the business end of the submachine gun had turned the other way. The face of the lieutenant revealed sheer agony. He must have thought that we were going to kill them right then and there. I motioned the Americans to sit down on a fallen log and told them briefly about the surrender of Colonel Steinmetz and our odyssey across Czechoslovakia. They seemed impressed.

“Are you telling me that the Russians just gunned them down under a flag of truce?” the lieutenant asked. “It is a helluva way of treating prisoners of war.”

“Indeed, Lieutenant?” I queried him sharply. “Do you consider hanging more sophisticated?”

“We aren’t going to hang anyone without a fair trial,” he protested.