Garth Nix was born in 1963 in Melbourne, Australia. A full-time writer since 2001, he has previously worked as a literary agent, marketing consultant, book editor, book publicist, book sales representative, bookseller, and as a part-time soldier in the Australian Army Reserve. Garth’s books include the award-winning fantasy novels , and; and the cult favourite YA SF novel . His fantasy novels for children include ; the six books ofsequence, and series. More than five million copies of his books have been sold around the world; his books have appeared on the bestseller lists of , , and; and his work has been translated into 37 languages. He lives in a Sydney beach suburb with his wife and two children.

Editors’ note:

‘Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again’ won the Aurealis Award for Best Fantasy Story of 2007.

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again

Garth Nix

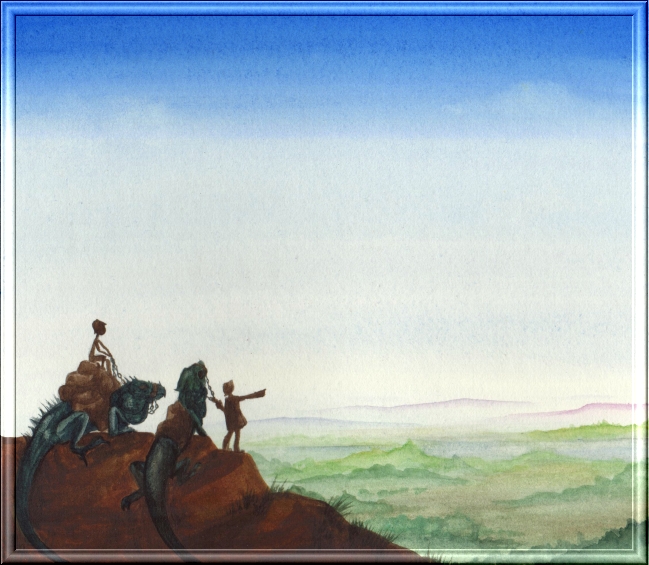

“Do you ever wonder about the nature of the world, Mister Fitz?” asked the foremost of the two riders, raising the three-barred visor of his helmet so that his words might more clearly cross the several feet of space that separated him from his companion, who rode not quite at his side.

“I take it much as it presents itself, for good or ill, Sir Hereward,” replied Mister Fitz. He had no need to raise a visor, for he wore a tall lacquered hat rather than a helmet. It had once been taller and had come to a peak, before encountering something sharp in the last battle but two the pair had found themselves engaged in. This did not particularly bother Mister Fitz, for he was not human. He was a wooden puppet given the semblance of life by an ancient sorcery. By dint of propinquity, over many centuries a considerable essence of humanity had been absorbed into his fine-grained body, but attention to his own appearance or indeed vanity of any sort was still not part of his persona.

Sir Hereward, for the other part, had a good measure of vanity and in fact the raising of the three-barred visor of his helmet almost certainly had more to do with an approaching apple seller of comely appearance than it did with a desire for clear communication to Mister Fitz.

The duo were riding south on a road that had once been paved and gloried in the name of the Southwest Toll Extension of the Lesser Trunk. But its heyday was long ago, the road being even older than Mister Fitz. Few paved stretches remained, but the tightly compacted understructure still provided a better surface than the rough soil of the fields to either side.

The political identification of these fallow pastures and the occasional once-coppiced wood they passed was not clear to either Sir Hereward or Mister Fitz, despite several attempts to ascertain said identification from the few travellers they had encountered since leaving the city of Rhool several days before. To all intents and purposes, the land appeared to be both uninhabited and untroubled by soldiery or tax collectors and was thus a void in the sociopolitical map that Hereward held uneasily, and Fitz exactly, in their respective heads.

A quick exchange with the apple seller provided only a little further information, and also lessened Hereward’s hope of some minor flirtation, for her physical beauty was sullied by a surly and depressive manner. In a voice as sullen as a three-day drizzle, the woman told them she was taking the apples to a large house that lay out of sight beyond the nearer overgrown wood. She had come from a town called Lettique or Letiki that was located beyond the lumpy ridge of blackish shale that they could see a mile or so to the south. The apples in question had come from farther south still, and were not in keeping with their carrier, being particularly fine examples of a variety Mister Fitz correctly identified as emerald brights. There was no call for local apples, the young woman reluctantly explained. The fruit and vegetables from the distant oasis of Shûme were always preferred, if they could be obtained. Which, for the right price, they nearly always could be, regardless of season.

Hereward and Fitz rode in silence for a few minutes after parting company with the apple seller, the young knight looking back not once but twice as if he could not believe that such a vision of loveliness could house such an unfriendly soul. Finding that the young woman did not bother to look back at all, Hereward cleared his throat and, without raising his visor, spoke.

“It appears we are on the right road, though she spoke of Shumey and not Shome.”

Fitz looked up at the sky, where the sun was beginning to lose its distinct shape and ooze red into the shabby grey clouds that covered the horizon.

“A minor variation in pronunciation,” he said. “Should we stop in Lettique for the night, or ride on?”

“Stop,” said Hereward. “My rear is not polished sandalwood, and it needs soaking in a very hot bath enhanced with several soothing essences . . . ah . . . that was one of your leading questions, wasn’t it?”

“The newspaper in Rhool spoke of an alliance against Shûme,” said Mister Fitz carefully, in a manner that confirmed Hereward’s suspicion that didactic discourse had already begun. “It is likely that Lettique will be one of the towns arrayed against Shûme. Should the townsfolk discover we ride to Shûme in hope of employment, we might find ourselves wishing for the quiet of the fields in the night, the lack of mattresses, ale and roasted capons there notwithstanding.”

“Bah!” exclaimed Hereward, whose youth and temperament made him tend toward careless optimism. “Why should they suspect us of seeking to sign on with the burghers of Shûme?”

Mister Fitz’s pumpkin-sized papier-mâché head rotated on his spindly neck, and the blobs of blue paint that marked the pupils of his eyes looked up and down, taking in Sir Hereward from toe to head: from his gilt-spurred boots to his gold-chased helmet. In between boots and helm was Hereward’s second-best buff coat, the sleeves still embroidered with the complicated silver tracery that proclaimed him as the Master Artillerist of the city of Jeminero. Not that said city was any longer in existence, as for the past three years it had been no more than a mass grave sealed with the rubble of its once-famous walls. Around the coat was a frayed but still quite golden sash, over that a rare and expensive Carnithian leather baldric and belt with two beautifully ornamented (but no less functional for that) wheel-lock pistols thrust through said belt. Hereward’s longer-barrelled and only slightly less ornamented cavalry pistols were holstered on either side of his saddle horn, his sabre with its sharkskin grip and gleaming hilt of gilt brass hung in its scabbard from the rear left quarter of his saddle, and his sighting telescope was secured inside its leather case on the right rear quarter.

Mister Fitz’s mount, of course, carried all the more mundane items required by their travels. All three feet six and a half inches of him (four-foot-three with the hat) was perched upon a yoke across his mount’s back that secured the two large panniers that were needed to transport tent and bedding, washing and shaving gear and a large assortment of outdoor kitchen utensils. Not to mention the small but surprisingly expandable sewing desk that contained the tools and devices of Mister Fitz’s own peculiar art.

“Shûme is a city, and rich,” said Fitz patiently. “The surrounding settlements are mere towns, both smaller and poorer, which are reportedly planning to go to war against their wealthy neighbour. You are obviously a soldier for hire, and a self-evidently expensive one at that. Therefore, you must be en route to Shûme.”

Hereward did not answer immediately, as was his way, while he worked at overcoming his resentment at being told what to do. He worked at it because Mister Fitz had been telling him what to do since he was four years old and also because he knew that, as usual, Fitz was right. It would be foolish to stop in Lettique.

“I suppose that they might even attempt to hire us,” he said, as they topped the low ridge, shale crunching under their mounts’ talons.

Hereward looked down at a wasted valley of underperforming pastures filled either with sickly-looking crops or passive groups of too-thin cattle. A town—presumably Lettique—lay at the other end of the valley. It was not an impressive ville, being a collection of perhaps three or four hundred mostly timber and painted-plaster houses within the bounds of a broken-down wall to the west and a dry ravine, that might have once held a river, to the east. An imposing, dozen-spired temple in the middle of the town was the only indication that at some time Lettique had seen more provident days.

“Do you wish to take employment in a poor town?” asked Mister Fitz. One of his responsibilities was to advise and positively influence Hereward, but he did not make decisions for him.

“No, I don’t think so,” replied the knight slowly. “Though it does make me recall my thought . . . the one that was with me before we were interrupted by that dismal apple seller.”

“You asked if I ever wondered at the nature of the world,” prompted Fitz.

“I think what I actually intended to say,” said Hereward. “Is ‘do you ever wonder why we become involved in events that are rather more than less of importance to rather more than less people?’ as in the various significant battles, sieges, and so forth in which we have played no small part. I fully comprehend that in some cases the events have stemmed from the peculiar responsibilities we shoulder, but not in all cases. And that being so, and given my desire for a period of quiet, perhaps I should consider taking service with some poor town.”

“Do you really desire a period of quiet?” asked Mister Fitz.

“Sometimes I think so. I should certainly like a time where I might reflect upon what it is I do want. It would also be rather pleasant to meet women who are not witch-agents, fellow officers or enemies—or who have been pressed into service as powder monkeys or are soaked in blood from tending the wounded.”

“Perhaps Shûme will offer some relative calm,” said Mister Fitz. “By all accounts it is a fine city, and even if war is in the offing, it could be soon finished if Shûme’s opponents are of a standard that I can see in Lettique.”

“You observe troops?” asked Hereward. He drew his telescope, and carefully leaning on his mount’s neck to avoid discomfort from the bony ridges (which even though regularly filed-down and fitted with leather stocks were not to be ignored), looked through it at the town. “Ah, I see. Sixty pike and two dozen musketeers in the square by the temple, of no uniform equipment or harness. Under the instruction of a portly individual in a wine-dark tunic who appears as uncertain as his troops as to the drill.”

“I doubt that Shûme has much to fear,” said Mister Fitz. “It is odd, however, that a town like Lettique would dare to strike against such a powerful neighbour. I wonder . . .”

“What?” asked Hereward as he replaced his telescope.

“I wonder if it is a matter of necessity. The river is dry. The wheat is very thin, too thin this close to harvest. The cattle show very little flesh on their ribs. I see no sign of any other economic activity. Fear and desperation may be driving this mooted war, not greed or rivalry. Also . . .”

Mister Fitz’s long, pale blue tongue darted out to taste the air, the ruby stud in the middle of what had once been a length of stippled leather catching the pallid sunlight.

“Their godlet is either asleep or . . . mmm . . . comatose in this dimension. Very strange.”

“Their god is dead?”

“Not dead,” said Mister Fitz. “When an other-dimensional entity dies, another always moves in quickly enough. No . . . definitely present, but quiescent.”

“Do you wish to make a closer inquiry?”

Hereward had not missed the puppet’s hand tapping the pannier that contained his sewing desk, an instinctive movement Mister Fitz made when contemplating sorcerous action.

“Not for the present,” said Mister Fitz, lifting his hand to grasp once again his mount’s steering chains.

“Then we will skirt the town and continue,” announced Hereward. “We’ll leave the road near those three dead trees.”

“There are many trees that might be fairly described as dead or dying,” remarked Fitz. “And several in clumps of three. Do you mean the somewhat orange-barked trio over yonder?”

“I do,” said Hereward.

They left the road at the clump of trees and rode in silence through the dry fields, most of which were not even under attempted cultivation. There were also several derelict farmhouses, barns, and cattle yards, the level of decay suggesting that the land had been abandoned only in recent years.

Halfway along the valley, where the land rose to a slight hill that might have its origin in a vast and ancient burial mound, Hereward reined in his mount and looked back at the town through his telescope.

“Still drilling,” he remarked. “I had half thought that they might dispatch some cavalry to bicker with us. But I see no mounts.”

“I doubt they can afford the meat for battlemounts,” said Mister Fitz. “Or grain for horses, for that matter.”

“There is an air gate in the northeastern temple spire,” said Hereward, rebalancing his telescope to get a steadier view. “There might be a moonshade roost behind it.”

“If their god is absent, none of the ancient weapons will serve them,” said Mister Fitz. “But it would be best to be careful, come nightfall. Lettique is reportedly not the only town arrayed against Shûme. The others may be in a more vigorous condition, with wakeful gods.”

Hereward replaced his telescope and turned his mount to the north, Mister Fitz following his lead. They did not speak further, but rode on, mostly at the steady pace that Hereward’s Zowithian riding instructor had called ‘the lope’, occasionally urging their mounts to the faster ‘jag’. In this fashion, several miles passed quickly. As the sun’s last third began to slip beneath the horizon, they got back on the old road again, to climb out of the wasted valley of Lettique and across yet another of the shale ridges that erupted out of the land like powder-pitted keloid scars, all grey and humped.

The valley that lay beyond the second ridge was entirely different from the faded fields behind the two travellers. In the warm twilight, they saw a checkerboard of green and gold, full fields of wheat interspersed with meadows heavily stocked with fat cattle. A broad river wound through from the east, spilling its banks in several places into fecund wetlands that were rich with waterfowl. Several small hillocks in the valley were covered in apple trees, dark foliage heavily flecked with the bright green of vast quantities of emerald fruit. There were citrus groves too, stone-walled clumps of smaller trees laden with lemons or limes, and only a hundred yards away, a group of six trees bearing the rare and exquisite blue-skinned fruit known as serqa which was normally only found in drier climes.

“A most pleasant vista,” said Hereward. A small smile curled his lip and touched his eyes, the expression of a man who sees something that he likes.

Shûme itself was a mile away, built on a rise in the ground in the northwestern corner of the valley, where the river spread into a broad lake that lapped the city’s western walls. From the number of deep-laden boats that were even now rowing home to the jetties that thronged the shore, the lake was as well stocked with fish as the valley was with livestock and produce.

Most of the city’s buildings were built of an attractively pale yellow stone, with far fewer timber constructions than was usual for a place that Hereward reckoned must hold at least five thousand citizens.

Shûme was also walled in the same pale stone, but of greater interest to Hereward were the more recent earthworks that had been thrown up in front of the old wall. A zigzag line of revetments encircled the city, with respectably large bastions at each end on the lakeshore. A cursory telescopic examination showed several bronze demicannon on the bastions and various lesser pieces of ordnance clustered in groups at various strong points along the earthworks. Both bastions had small groups of soldiery in attendance on the cannon, and there were pairs of sentries every twenty or thirty yards along the earthen ramparts and a score or more walked the stone walls behind.

“There is certainly a professional in charge here,” observed Hereward. “I expect . . . yes . . . a cavalry piquet issues from yonder orchard. Twelve horse troopers under the notional command of a whey-faced cornet.”

“Not commonplace troopers,” added Mister Fitz. “Dercian keplars.”

“Ah,” said Hereward. He replaced his telescope, leaned back a little and across and, using his left hand, loosened his sabre so that an inch of blade projected from the scabbard. “They are in employment, so they should give us the benefit of truce.”

“They should,” conceded Mister Fitz, but he reached inside his robe to grasp some small item concealed under the cloth. With his other hand he touched the brim of his hat, releasing a finely woven veil that covered his face. To casual inspection he now looked like a shrouded child, wearing peculiar papery gloves. Self-motivated puppets were not great objects of fear in most quarters of the world. They had once been numerous, and some few score still walked the earth, almost all of them entertainers, some of them long remembered in song and story.

Mister Fitz was not one of those entertainers.

“If it comes to it, spare the cornet,” said Hereward, who remembered well what it was like to be a very junior officer, whey-faced or not.

Mister Fitz did not answer. Hereward knew as well as he that if it came to fighting, and the arts the puppet employed, there would be no choosing who among those who opposed them lived or died.

The troop rode toward the duo at a canter, slowing to a walk as they drew nearer and their horses began to balk as they scented the battlemounts. Hereward raised his hand in greeting and the cornet shouted a command, the column extending to a line, then halting within an easy pistol shot. Hereward watched the troop sergeant, who rode forward beyond the line for a better look, then wheeled back at speed toward the cornet. If the Dercians were to break their oath, the sergeant would fell her officer first.

But the sergeant halted without drawing a weapon and spoke to the cornet quietly. Hereward felt a slight easing of his own breath, though he showed no outward sign of it and did not relax. Nor did Mister Fitz withdraw his hand from under his robes. Hereward knew that his companion’s moulded papier-mâché fingers held an esoteric needle, a sliver of some arcane stuff that no human hand could grasp with impunity.

The cornet listened and spoke quite sharply to the sergeant, turning his horse around so that he could make his point forcefully to the troopers as well. Hereward only caught some of the words, but it seemed that despite his youth, the officer was rather more commanding than he had expected, reminding the Dercians that their oaths of employment overrode any private or societal vendettas they might wish to undertake.

When he had finished, the cornet shouted, “Dismount! Sergeant, walk the horses!”

The officer remained mounted, wheeling back to approach Hereward. He saluted as he reined in a cautious distance from the battlemounts, evidently not trusting either the creatures’ blinkers and mouth-cages or his own horse’s fears.

“Welcome to Shûme!” he called. “I am Cornet Misolu. May I ask your names and direction, if you please?”

“I am Sir Hereward of the High Pale, artillerist for hire.”

“And I am Fitz, also of the High Pale, aide de camp to Sir Hereward.”

“Welcome . . . uh . . . sirs,” said Misolu. “Be warned that war has been declared upon Shûme, and all who pass through must declare their allegiances and enter certain . . . um . . .”

“I believe the usual term is ‘undertakings’,” said Mister Fitz.

“Undertakings,” echoed Misolu. He was very young. Two bright spots of embarrassment burned high on his cheekbones, just visible under the four bars of his lobster-tailed helmet, which was a little too large for him, even with the extra padding, some of which had come a little undone around the brow.

“We are free lances, and seek hire in Shûme, Cornet Misolu,” said Hereward. “We will give the common undertakings if your city chooses to contract us. For the moment, we swear to hold our peace, reserving the right to defend ourselves should we be attacked.”

“Your word is accepted, Sir Hereward, and . . . um . . .”

“Mister Fitz,” said Hereward, as the puppet said merely, “Fitz.”

“Mister Fitz.”

The cornet chivvied his horse diagonally closer to Hereward, and added, “You may rest assured that my Dercians will remain true to their word, though Sergeant Xikoliz spoke of some feud their . . . er . . . entire people have with you.”

The curiosity in the cornet’s voice could not be easily denied, and spoke as much of the remoteness of Shûme as it did of the young officer’s naïveté.

“It is a matter arising from a campaign several years past,” said Hereward. “Mister Fitz and I were serving the Heriat of Jhaqa, who sought to redirect the Dercian spring migration elsewhere than through her own prime farmlands. In the last battle of that campaign, a small force penetrated to the Dercians’ rolling temple and . . . ah . . . blew it up with a specially made petard. Their godlet, thus discommoded, withdrew to its winter housing in the Dercian steppe, wreaking great destruction among its chosen people as it went.”

“I perceive you commanded that force, sir?”

Hereward shook his head.

“No, I am an artillerist. Captain Kasvik commanded. He was slain as we retreated—another few minutes and he would have won clear. However, I did make the petard, and . . . Mister Fitz assisted our entry to the temple and our escape. Hence the Dercians’ feud.”

Hereward looked sternly at Mister Fitz as he spoke, hoping to make it clear that this was not a time for the puppet to exhibit his tendency for exactitude and truthfulness. Captain Kasvik had in fact been killed before they even reached the rolling temple, but it had served his widow and family better for Kasvik to be a hero, so Hereward had made him one. Only Mister Fitz and one other survivor of the raid knew otherwise.

Not that Hereward and Fitz considered the rolling temple action a victory, as their intent had been to force the Dercian godlet to withdraw a distance unimaginably more vast than the mere five hundred leagues to its winter temple.

The ride to the city was uneventful, though Hereward could not help but notice that Cornet Misolu ordered his troop to remain in place and keep watch, while he alone escorted the visitors, indicating that the young officer was not absolutely certain the Dercians would hold to their vows.

There was a zigzag entry through the earthwork ramparts, where they were held up for several minutes in the business of passwords and responses (all told aside in quiet voices, Hereward noted with approval), their names being recorded in an enormous ledger and passes written out and sealed allowing them to enter the city proper.

These same passes were inspected closely under lanternlight, only twenty yards farther on by the guards outside the city gate—which was closed, as the sun had finally set. However, they were admitted through a sally port and here Misolu took his leave, after giving directions to an inn that met Hereward’s requirements: suitable stabling and food for the battlemounts; that it not be the favourite of the Dercians or any other of the mercenary troops who had signed on in preparation for Shûme’s impending war; and fine food and wine, not just small beer and ale. The cornet also gave directions to the citadel, not that this was really necessary as its four towers were clearly visible, and advised Hereward and Fitz that there was no point going there until the morning, for the governing council was in session and so no one in authority could hire him until at least the third bell after sunrise.

The streets of Shûme were paved and drained, and Hereward smiled again at the absence of the fetid stench so common to places where large numbers of people dwelt together. He was looking forward to a bath, a proper meal and a fine feather bed, with the prospect of well-paid and not too onerous employment commencing on the morrow.

“There is the inn,” remarked Mister Fitz, pointing down one of the narrower side streets, though it was still broad enough for the two battlemounts to stride abreast. “The sign of the golden barleycorn. Appropriate enough for a city with such fine farmland.”

They rode into the inn’s yard, which was clean and wide and did indeed boast several of the large iron-barred cages used to stable battlemounts complete with meat canisters and feeding chutes rigged in place above the cages. One of the four ostlers present ran ahead to open two cages and lower the chutes, and the other three assisted Hereward to unload the panniers. Mister Fitz took his sewing desk and stood aside, the small rosewood-and-silver box under his arm provoking neither recognition nor alarm. The ostlers were similarly incurious about Fitz himself, almost certainly evidence that self-motivated puppets still came to entertain the townsfolk from time to time.

Hereward led the way into the inn, but halted just before he entered as one of the battlemounts snorted at some annoyance. Glancing back, he saw that it was of no concern, and the gates were closed, but in halting he had kept hold of the door as someone else tried to open it from the other side. Hereward pushed to help and the door flung open, knocking the person on the inside back several paces against a table, knocking over an empty bottle that smashed upon the floor.

“Unfortunate,” muttered Mister Fitz, as he saw that the person so inconvenienced was not only a soldier, but wore the red sash of a junior officer, and was a woman.

“I do apolog—” Hereward began to say. He stopped, not only because the woman was talking, but because he had looked at her. She was as tall as he was, with ash-blond hair tied in a queue at the back, her hat in her left hand. She was also very beautiful, at least to Hereward, who had grown up with women who ritually cut their flesh. To others, her attractiveness might be considered marred by the scar that ran from the corner of her left eye out toward the ear and then cut back again toward the lower part of her nose.

“You are clumsy, sir!”

Hereward stared at her for just one second too long before attempting to speak again.

“I am most—”

“You see something you do not like, I think?” interrupted the woman. “Perhaps you have not served with females? Or is it my face you do not care for?”

“You are very beautiful,” said Hereward, even as he realized it was entirely the wrong thing to say, either to a woman he had just met or an officer he had just run into.

“You mock me!” swore the woman. Her blue eyes shone more fiercely, but her face paled, and the scar grew more livid. She clapped her broad-brimmed hat on her head and straightened to her full height, with the hat standing perhaps an inch over Hereward. “You shall answer for that!”

“I do not mock you,” said Hereward quietly. “I have served with men, women . . . and eunuchs, for that matter. Furthermore, tomorrow morning I shall be signing on as at least colonel of artillery, and a colonel may not fight a duel with a lieutenant. I am most happy to apologize, but I cannot meet you.”

“Cannot or will not?” sneered the woman. “You are not yet a colonel in Shûme’s service, I believe, but just a mercenary braggart.”

Hereward sighed and looked around the common room.

Misolu had spoken truly that the inn was not a mercenary favourite. But there were several officers of Shûme’s regular service or militia, all of them looking on with great attention.

“Very well,” he snapped. “It is foolishness, for I intended no offence. When and where?”

“Immediately,” said the woman. “There is a garden a little way behind this inn. It is lit by lanterns in the trees, and has a lawn.”

“How pleasant,” said Hereward. “What is your name, madam?”

“I am Lieutenant Jessaye of the Temple Guard of Shûme. And you are?”

“I am Sir Hereward of the High Pale.”

“And your friends, Sir Hereward?”

“I have only this moment arrived in Shûme, Lieutenant, and so cannot yet name any friends. Perhaps someone in this room will stand by me, should you wish a second. My companion, whom I introduce to you now, is known as Mister Fitz. He is a surgeon—among other things—and I expect he will accompany us.”

“I am pleased to meet you, Lieutenant,” said Mister Fitz. He doffed his hat and veil, sending a momentary frisson of small twitches among all in the room save Hereward.

Jessaye nodded back but did not answer Fitz. Instead she spoke to Hereward.

“I need no second. Should you wish to employ sabres, I must send for mine.”

“I have a sword in my gear,” said Hereward. “If you will allow me a few minutes to fetch it?”

“The garden lies behind the stables,” said Jessaye. “I will await you there. Pray do not be too long.”

Inclining her head but not doffing her hat, she stalked past and out the door.

“An inauspicious beginning,” said Fitz.

“Very,” said Hereward gloomily. “On several counts. Where is the innkeeper? I must change and fetch my sword.”

****

The garden was very pretty. Railed in iron, it was not gated, and so accessible to all the citizens of Shûme. A wandering path led through a grove of lantern-hung trees to the specified lawn, which was oval and easily fifty yards from end to end, making the centre rather a long way from the lanternlight, and hence quite shadowed. A small crowd of persons who had previously been in the inn were gathered on one side of the lawn. Lieutenant Jessaye stood in the middle, naked blade in hand.

“Do be careful, Hereward,” said Fitz quietly, observing the woman flex her knees and practice a stamping attack ending in a lunge. “She looks to be very quick.”

“She is an officer of their temple guard,” said Hereward in a hoarse whisper. “Has their god imbued her with any particular vitality or puissance?”

“No, the godlet does not seem to be a martial entity,” said Fitz. “I shall have to undertake some investigations presently, as to exactly what it is—”

“Sir Hereward! Here at last.”

Hereward grimaced as Jessaye called out. He had changed as quickly as he could, into a very fine suit of split-sleeved white showing the yellow shirt beneath, with gold ribbons at the cuffs, shoulders and front lacing, with similarly cut bloomers of yellow showing white breeches, with silver ribbons at the knees, artfully displayed through the side-notches of his second-best boots.

Jessaye, in contrast, had merely removed her uniform coat and stood in her shirt, blue waistcoat, leather breeches and unadorned black thigh boots folded over below the knee. Had the circumstances been otherwise, Hereward would have paused to admire the sight she presented and perhaps offer a compliment.

Instead he suppressed a sigh, strode forward, drew his sword and threw the scabbard aside.

“I am here, Lieutenant, and I am ready. Incidentally, is this small matter to be concluded by one or perhaps both of us dying?”

“The city forbids duels to the death, Sir Hereward,” replied Jessaye. “Though accidents do occur.”

“What, then, is to be the sign for us to cease our remonstrance?”

“Blood,” said Jessaye. She flicked her sword towards the onlookers. “Visible to those watching.”

Hereward nodded slowly. In this light, there would need to be a lot of blood before the onlookers could see it. He bowed his head but did not lower his eyes, then raised his sword to the guard position.

Jessaye was fast. She immediately thrust at his neck, and though Hereward parried, he had to step back. She carried through to lunge in a different line, forcing him back again with a more awkward parry, removing all opportunity for Hereward to riposte or counter. For a minute they danced, their swords darting up, down and across, clashing together only to move again almost before the sound reached the audience.

In that minute, Hereward took stock of Jessaye’s style and action. She was very fast, but so was he, much faster than anyone would expect from his size and build, and, as always, he had not shown just how truly quick he could be. Jessaye’s wrist was strong and supple, and she could change both attacking and defensive lines with great ease. But her style was rigid, a variant of an old school Hereward had studied in his youth.

On her next lunge—which came exactly where he anticipated—Hereward didn’t parry but stepped aside and past the blade. He felt her sword whisper by his ribs as he angled his own blade over it and with the leading edge of the point, he cut Jessaye above the right elbow to make a long, very shallow slice that he intended should bleed copiously without inflicting any serious harm.

Jessaye stepped back but did not lower her guard. Hereward quickly called out, “Blood!”

Jessaye took a step forward and Hereward stood ready for another attack. Then the lieutenant bit her lip and stopped, holding her arm toward the lanternlight so she could more clearly see the wound. Blood was already soaking through the linen shirt, a dark and spreading stain upon the cloth.

“You have bested me,” she said, and thrust her sword point first into the grass before striding forward to offer her gloved hand to Hereward. He too grounded his blade, and took her hand as they bowed to each other.

A slight stinging low on his side caused Hereward to look down. There was a two-inch cut in his shirt, and small beads of blood were blossoming there. He did not let go Jessaye’s fingers, but pointed at his ribs with his left hand.

“I believe we are evenly matched. I hope we may have no cause to bicker further?”

“I trust not,” said Jessaye quietly. “I regret the incident. Were it not for the presence of some of my fellows, I should not have cavilled at your apology, sir. But you understand . . . a reputation is not easily won, nor kept . . .”

“I do understand,” said Hereward. “Come, let Mister Fitz attend your cut. Perhaps you will then join me for small repast?”

Jessaye shook her head.

“I go on duty soon. A stitch or two and a bandage are all I have time for. Perhaps we shall meet again.”

“It is my earnest hope that we do,” said Hereward. Reluctantly, he opened his grasp. Jessaye’s hand lingered in his palm for several moments before she slowly raised it, stepped back and doffed her hat to offer a full bow. Hereward returned it, straightening up as Mister Fitz hurried over, carrying a large leather case as if it were almost too heavy for him, one of his standard acts of misdirection, for the puppet was at least as strong as Hereward, if not stronger.

“Attend to Lieutenant Jessaye, if you please, Mister Fitz,” said Hereward. “I am going back to the inn to have a cup . . . or two . . . of wine.”

“Your own wound needs no attention?” asked Fitz as he set his bag down and indicated to Jessaye to sit by him.

“A scratch,” said Hereward. He bowed to Jessaye again and walked away, ignoring the polite applause of the onlookers, who were drifting forward either to talk to Jessaye or gawp at the blood on her sleeve.

“I may take a stroll,” called out Mister Fitz after Hereward. “But I shan’t be longer than an hour.”

****

Mister Fitz was true to his word, returning a few minutes after the citadel bell had sounded the third hour of the evening. Hereward had bespoken a private chamber and was dining alone there, accompanied only by his thoughts.

“The god of Shûme,” said Fitz, without preamble. “Have you heard anyone mention its name?”

Hereward shook his head and poured another measure from the silver jug with the swan’s beak spout. Like many things he had found in Shûme, the knight liked the inn’s silverware.

“They call their godlet Tanesh,” said Fitz. “But its true name is Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob.”

“As difficult to say or spell, I wager,” said Hereward. “I commend the short form, it shows common sense. What of it?”

“It is on the list,” said Fitz.

Hereward bit the edge of pewter cup and put it down too hard, slopping wine upon the table.

“You’re certain? There can be no question?”

Fitz shook his head. “After I had doctored the young woman, I went down to the lake and took a slide of the god’s essence—it was quite concentrated in the water, easily enough to yield a sample. You may compare it with the record, if you wish.”

He proffered a finger-long inch-wide strip of glass that was striated in many different bands of colour. Hereward accepted it reluctantly, and with it a fat, square book that Fitz slid across the table. The book was open at a hand-tinted colour plate, the illustration showing a sequence of colour bands.

“It is the same,” agreed the knight, his voice heavy with regret. “I suppose it is fortunate we have not yet signed on, though I doubt they will see what we do as being purely a matter of defence.”

“They do not know what they harbor here,” said Fitz.

“It is a pleasant city.” said Hereward, taking up his cup again to take a large gulp of the slightly sweet wine. “In a pretty valley. I had thought I could grow more than accustomed to Shûme—and its people.”

“The bounty of Shûme, all its burgeoning crops, its healthy stock and people, is an unintended result of their godlet’s predation upon the surrounding lands,” said Fitz. “Pralqornrah is one of the class of cross-dimensional parasites that is most dangerous. Unchecked, in time it will suck the vital essence out of all the land beyond its immediate demesne. The deserts of Balkash are the work of a similar being, over six millennia. This one has only been embedded here for two hundred years—you have seen the results beyond this valley.”

“Six millennia is a long time,” said Hereward, taking yet another gulp. The wine was strong as well as sweet, and he felt the need of it. “A desert might arise in that time without the interference of the gods.”

“It is not just the fields and the river that Pralqornrah feeds upon,” said Fitz. “The people outside this valley suffer too. Babes unborn, strong men and women declining before their prime . . . this godlet slowly sucks the essence from all life.”

“They could leave,” said Hereward. The wine was making him feel both sleepy and mulish. “I expect many have already left to seek better lands. The rest could be resettled, the lands left uninhabited to feed the godlet. Shûme could continue as an oasis. What if another desert grows around it? They occur in nature, do they not?”

“I do not think you fully comprehend the matter,” said Fitz. “Pralqornrah is a most comprehensive feeder. Its energistic threads will spread farther and faster the longer it exists here, and it in turn will grow more powerful and much more difficult to remove. A few millennia hence, it might be too strong to combat.”

“I am only talking,” said Hereward, not without some bitterness. “You need not waste your words to bend my reason. I do not even need to understand anything beyond the salient fact: this godlet is on the list.”

“Yes,” said Mister Fitz. “It is on the list.”

Hereward bent his head for a long, silent moment. Then he pushed his chair back and reached across for his sabre. Drawing it, he placed the blade across his knees. Mister Fitz handed him a whetstone and a small flask of light, golden oil. The knight oiled the stone and began to hone the sabre’s blade. A repetitive rasp was the only sound in the room for many minutes, till he finally put the stone aside and wiped the blade clean with a soft piece of deerskin.

“When?”

“Fourteen minutes past the midnight hour is optimum,” replied Mister Fitz. “Presuming I have calculated its intrusion density correctly.”

“It is manifest in the temple?”

Fitz nodded.

“Where is the temple, for that matter? Only the citadel stands out above the roofs of the city.”

“It is largely underground,” said Mister Fitz. “I have found a side entrance, which should not prove difficult. At some point beyond that there is some form of arcane barrier—I have not been able to ascertain its exact nature, but I hope to unpick it without trouble.”

“Is the side entrance guarded? And the interior?”

“Both,” said Fitz. Something about his tone made Hereward fix the puppet with a inquiring look.

“The side door has two guards,” continued Fitz. “The interior watch is of ten or eleven . . . led by the Lieutenant Jessaye you met earlier.”

Hereward stood up, the sabre loose in his hand, and turned away from Fitz.

“Perhaps we shall not need to fight her . . . or her fellows.”

Fitz did not answer, which was answer enough.

****

The side door to the temple was unmarked and appeared no different than the other simple wooden doors that lined the empty street, most of them adorned with signs marking them as the shops of various tradesmen, with smoke-grimed night lamps burning dimly above the sign. The door Fitz indicated was painted a pale violet and had neither sign nor lamp.

“Time to don the brassards and make the declaration,” said the puppet. He looked up and down the street, making sure that all was quiet, before handing Hereward a broad silk armband five fingers wide. It was embroidered with sorcerous thread that shed only a little less light than the smoke-grimed lantern above the neighbouring shop door. The symbol the threads wove was one that had once been familiar the world over but was now unlikely to be recognized by anyone save an historian . . . or a god.

Hereward slipped the brassard over his left glove and up his thick coat sleeve, spreading it out above the elbow. The suit of white and yellow was once again packed, and for this expedition the knight had chosen to augment his helmet and buff coat with a dented but still eminently serviceable back- and breastplate, the steel blackened by tannic acid to a dark grey. He had already primed, loaded and spanned his two wheel-lock pistols, which were thrust through his belt; his sabre was sheathed at his side; and a lozenge-sectioned, armour-punching bodkin was in his left boot.

Mister Fitz wore his sewing desk upon his back, like a wooden backpack. He had already been through its numerous small drawers and containers and selected particular items that were now tucked into the inside pockets of his coat, ready for immediate use.

“I wonder why we bother with this mummery,” grumbled Hereward. But he stood at attention as Fitz put on his own brassard, and the knight carefully repeated the short phrase uttered by his companion. Though both had recited it many times, and it was clear as bright type in their minds, they spoke carefully and with great concentration, in sharp contrast to Hereward’s remark about mummery.

“In the name of the Council of the Treaty for the Safety of the World, acting under the authority granted by the Three Empires, the Seven Kingdoms, the Palatine Regency, the Jessar Republic and the Forty Lesser Realms, we declare ourselves agents of the Council. We identify the godlet manifested in this city of Shûme as Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob, a listed entity under the Treaty. Consequently, the said godlet and all those who assist it are deemed to be enemies of the World and the Council authorizes us to pursue any and all actions necessary to banish, repel or exterminate the said godlet.”

Neither felt it necessary to change this ancient text to reflect the fact that only one of the three empires was still extant in any fashion; that the seven kingdoms were now twenty or more small states; the Palatine Regency was a political fiction, its once broad lands under two fathoms of water; the Jessar Republic was now neither Jessar in ethnicity nor a republic; and perhaps only a handful of the Forty Lesser Realms resembled their antecedent polities in any respect. But for all that the states that had made it were vanished or diminished, the Treaty for the Safety of the World was still held to be in operation, if only by the Council that administered and enforced it.

“Are you ready?” asked Fitz.

Hereward drew his sabre and moved into position to the left of the door. Mister Fitz reached into his coat and drew out an esoteric needle. Hereward knew better than to try to look at the needle directly, but in the reflection of his blade, he could see a four-inch line of something intensely violet writhe in Fitz’s hand. Even the reflection made him feel as if he might at any moment be unstitched from the world, so he angled the blade away.

At that moment, Fitz touched the door with the needle and made three short plucking motions. On the last motion, without any noise or fuss, the door wasn’t there anymore. There was only a wood-panelled corridor leading down into the ground and two very surprised temple guards, who were still leaning on their halberds.

Before Hereward could even begin to move, Fitz’s hand twitched across and up several times. The lanterns on their brass stands every six feet along the corridor flickered and flared violet for a fraction of a second. Hereward blinked, and the guards were gone, as were the closest three lanterns and their stands.

Only a single drop of molten brass, no bigger than a tear, remained. It sizzled on the floor for a second, then all was quiet.

The puppet stalked forward, cupping his left hand over the needle in his right, obscuring its troublesome sight behind his fingers. Hereward followed close behind, alert for any enemy that might be resistant to Fitz’s sorcery.

The corridor was a hundred yards long by Hereward’s estimation, and slanted sharply down, making him think about having to fight back up it, which would be no easy task, made more difficult as the floor and walls were damp, drops of water oozing out between the floorboards and dripping from the seams of the wall panelling. There was cold, wet stone behind the timber, Hereward knew. He could feel the cold air rippling off it, a chill that no amount of fine timber could cloak.

The corridor ended at what appeared from a distance to be a solid wall, but closer to was merely the dark back of a heavy tapestry. Fitz edged silently around it, had a look, and returned to beckon Hereward in.

There was a large antechamber or waiting room beyond, sparsely furnished with a slim desk and several well-upholstered armchairs. The desk and chairs each had six legs, the extra limbs arranged closely at the back, a fashion Hereward supposed was some homage to the godlet’s physical manifestation. The walls were hung with several tapestries depicting the city at various stages in its history.

Given the depth underground and the proximity of the lake, great efforts must have been made to waterproof and beautify the walls, floor and ceiling, but there was still an army of little dots of mould advancing from every corner, blackening the white plaster and tarnishing the gilded cornices and decorations.

Apart from the tapestry-covered exit, there were three doors. Two were of a usual size, though they were elaborately carved with obscure symbols and had brass, or perhaps even gold, handles. The one on the wall opposite the tapestry corridor was entirely different: it was a single ten-foot-by-six-foot slab of ancient marble veined with red lead, and it would have been better situated sitting on top of a significant memorial or some potentate’s coffin.

Mister Fitz went to each of the carved doors, his blue tongue flickering in and out, sampling the air.

“No one close,” he reported, before approaching the marble slab. He actually licked the gap between the stone and the floor, then sat for a few moments to think about what he had tasted.

Hereward kept clear, checking the other doors to see if they could be locked. Disappointed in that aim as they had neither bar nor keyhole, he sheathed his sabre and carefully and quietly picked up a desk to push against the left door and several chairs to pile against the right. They wouldn’t hold, but they would give some warning of attempted ingress.

Fitz chuckled as Hereward finished his work, an unexpected noise that made the knight shiver, drop his hand to the hilt of his sabre, and quickly look around to see what had made the puppet laugh. Fitz was not easily amused, and often not by anything Hereward would consider funny.

“There is a sorcerous barrier,” said Fitz. “It is immensely strong but has not perhaps been as well thought-out as it might have been. Fortuitously, I do not even need to unpick it.”

The puppet reached up with his left hand and pushed the marble slab. It slid back silently, revealing another corridor, this one of more honest bare, weeping stone, rapidly turning into rough-hewn steps only a little way along.

“I’m afraid you cannot follow, Hereward,” said Fitz. “The barrier is conditional, and you do not meet its requirements. It would forcibly—and perhaps harmfully—repel you if you tried to step over the lintel of this door. But I would ask you to stay here in any case, to secure our line of retreat. I should only be a short time if all goes well. You will, of course, know if all does not go well, and must save yourself as best you can. I have impressed the ostlers to rise at your command and load our gear, as I have impressed instructions into the dull minds of the battlemounts—”

“Enough, Fitz! I shall not leave without you.”

“Hereward, you know that in the event of my—”

“Fitz. The quicker it were done—”

“Indeed. Be careful, child.”

“Fitz!”

But the puppet had gone almost before that exasperated single word was out of Hereward’s mouth.

It quickly grew cold with the passage below open. Chill, wet gusts of wind blew up and followed the knight around the room, no matter where he stood. After a few minutes trying to find a spot where he could avoid the cold breeze, Hereward took to pacing by the doors as quietly as he could. Every dozen steps or so he stopped to listen, either for Fitz’s return or the sound of approaching guards.

In the event, he was midpace when he heard something. The sharp beat of hobnailed boots in step, approaching the left-hand door.

Hereward drew his two pistols and moved closer to the door. The handle rattled, the door began to move and encountered the desk he had pushed there. There was an exclamation and several voices spoke all at once. A heavier shove came immediately, toppling the desk as the door came partially open.

Hereward took a pace to the left and fired through the gap. The wheel locks whirred, sparks flew, then there were two deep, simultaneous booms, the resultant echoes flattening down the screams and shouts in the corridor beyond the door, just as the conjoining clouds of blue-white smoke obscured Hereward from the guards, who were already clambering over their wounded or slain companions.

The knight thrust his pistols back through his belt and drew his sabre, to make an immediate sweeping cut at the neck of a guard who charged blindly through the smoke, his halberd thrust out in front like a blind man’s cane. Man and halberd clattered to the floor. Hereward ducked under a halberd swing and slashed the next guard behind the knees, at the same time picking up one edge of the desk and flipping it upright in the path of the next two guards. They tripped over it, and Hereward stabbed them both in the back of the neck as their helmets fell forward, left-right, three inches of sabre point in and out in an instant.

A blade skidded off Hereward’s cuirass and would have scored his thigh but for a quick twist away. He parried the next thrust, rolled his wrist and slashed his attacker across the stomach, following it up with a kick as the guard reeled back, sword slack in his hand.

No attack—or any movement save for dulled writhing on the ground—followed. Hereward stepped back and surveyed the situation. Two guards were dead or dying just beyond the door. One was still to his left. Three lay around the desk. Another was hunched over by the wall, his hands pressed uselessly against the gaping wound in his gut, as he moaned the god’s name over and over.

None of the guards was Jessaye, but the sound of the pistol shots at the least would undoubtedly bring more defenders of the temple.

“Seven,” said Hereward. “Of a possible twelve.”

He laid his sabre across a chair and reloaded his pistols, taking powder cartridges and shot from the pocket of his coat and a ramrod from under the barrel of one gun. Loaded, he wound their wheel-lock mechanisms with a small spanner that hung from a braided-leather loop on his left wrist.

Just as he replaced the pistols in his belt, the ground trembled beneath his feet, and an even colder wind came howling out of the sunken corridor, accompanied by a cloying but not unpleasant odour of exotic spices that also briefly made Hereward see strange bands of colour move through the air, the visions fading as the scent also passed.

Tremors, scent and strange visions were all signs that Fitz had joined battle with Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob below. There could well be other portents to come, stranger and more unpleasant to experience.

“Be quick, Fitz,” muttered Hereward, his attention momentarily focused on the downwards passage.

Even so, he caught the soft footfall of someone sneaking in, boots left behind in the passage. He turned, pistols in hand, as Jessaye stepped around the half-open door. Two guards came behind her, their own pistols raised.

Before they could aim, Hereward fired and, as the smoke and noise filled the room, threw the empty pistols at the trio, took up his sabre and jumped aside.

Jessaye’s sword leapt into the space where he’d been. Hereward landed, turned and parried several frenzied stabs at his face, the swift movement of their blades sending the gun smoke eddying in wild roils and coils. Jessaye pushed him back almost to the other door. There, Hereward picked up a chair and used it to fend off several blows, at the same time beginning to make small, fast cuts at Jessaye’s sword arm.

Jessaye’s frenzied assault slackened as Hereward cut her badly on the shoulder near her neck, then immediately after that on the upper arm, across the wound he’d given her in the duel. She cried out in pain and rage and stepped back, her right arm useless, her sword point trailing on the floor.

Instead of pressing his attack, the knight took a moment to take stock of his situation.

The two pistol-bearing guards were dead or as good as, making the tally nine. That meant there should only be two more, in addition to Jessaye, and those two were not immediately in evidence.

“You may withdraw, if you wish,” said Hereward, his voice strangely loud and dull at the same time, a consequence of shooting in enclosed spaces. “I do not wish to kill you, and you cannot hold your sword.”

Jessaye transferred her sword to her left hand and took a shuddering breath.

“I fight equally well with my left hand,” she said, assuming the guard position as best she could, though her right arm hung at her side, and blood dripped from her fingers to the floor.

She thrust immediately, perhaps hoping for surprise. Hereward ferociously beat her blade down, then stamped on it, forcing it from her grasp. He then raised the point of his sabre to her throat.

“No you don’t,” he said. “Very few people do. Go, while you still live.”

“I cannot,” whispered Jessaye. She shut her eyes. “I have failed in my duty. I shall die with my comrades. Strike quickly.”

Hereward raised his elbow and prepared to push the blade through the so-giving flesh, as he had done so many times before. But he did not, instead he lowered his sabre and backed away around the wall.

“Quickly, I beg you,” said Jessaye. She was shivering, the blood flowing faster down her arm.

“I cannot,” muttered Hereward. “Or rather I do not wish to. I have killed enough today.”

Jessaye opened her eyes and slowly turned to him, her face paper white, the scar no brighter than the petal of a pink rose. For the first time, she saw that the stone door was open, and she gasped and looked wildly around at the bodies that littered the floor.

“The priestess came forth? You have slain her?”

“No,” said Hereward. He continued to watch Jessaye and listen for others, as he bent and picked up his pistols. They were a present from his mother, and he had not lost them yet. “My companion has gone within.”

“But that . . . that is not possible! The barrier—”

“Mister Fitz knew of the barrier,” said Hereward wearily. He was beginning to feel the aftereffects of violent combat, and strongly desired to be away from the visible signs of it littered around him. “He crossed it without difficulty.”

“But only the priestess can pass,” said Jessaye wildly. She was shaking more than just shivering now, as shock set in, though she still stood upright. “A woman with child! No one and nothing else! It cannot be . . .”

Her eyes rolled back in her head, she twisted sideways and fell to the floor. Hereward watched her lie there for a few seconds while he attempted to regain the cold temper in which he fought, but it would not return. He hesitated, then wiped his sabre clean, sheathed it, then despite all better judgment, bent over Jessaye.

She whispered something and again, and he caught the god’s name, “Tanesh” and with it a sudden onslaught of cinnamon and cloves and ginger on his nose. He blinked, and in that blink, she turned and struck at him with a small dagger that had been concealed in her sleeve. Hereward had expected something, but not the god’s assistance, for the dagger was in her right hand, which he’d thought useless. He grabbed her wrist but could only slow rather than stop the blow. Jessaye struck true, the dagger entering the armhole of the cuirass, to bite deep into his chest.

Hereward left the dagger there and merely pushed Jessaye back. The smell of spices faded, and her arm was limp once more. She did not resist, but lay there quite still, only her eyes moving as she watched Hereward sit down next to her. He sighed heavily, a few flecks of blood already spraying out with his breath, evidence that her dagger was lodged in his lung though he already knew that from the pain that impaled him with every breath.

“There is no treasure below,” said Jessaye quietly. “Only the godlet, and his priestess.”

“We did not come for treasure,” said Hereward. He spat blood on the floor. “Indeed, I had thought we would winter here, in good employment. But your god is proscribed, and so . . .”

“Proscribed? I don’t . . . who . . .”

“By the Council of the Treaty for the Safety of the World,” said Hereward. “Not that anyone remembers that name. If we are remembered it is from the stories that tell of . . . god-slayers.”

“I know the stories,” whispered Jessaye. “And not just stories . . . we were taught to beware the god-slayers. But they are always women, barren women, with witch-scars on their faces. Not a man and a puppet. That is why the barrier . . . the barrier stops all but gravid women . . .”

Hereward paused to wipe a froth of blood from his mouth before he could answer.

“Fitz has been my companion since I was three years old. He was called Mistress Fitz then, as my nurse-bodyguard. When I turned ten, I wanted a male companion, and so I began to call him Mister Fitz. But whether called Mistress or Master, I believe Fitz is nurturing an offshoot of his spiritual essence in some form of pouch upon his person. In time he will make a body for it to inhabit. The process takes several hundred years.”

“But you . . .”

Jessaye’s whisper was almost too quiet to hear.

“I am a mistake . . . the witches of Har are not barren, that is just a useful tale. But they do only bear daughters . . . save the once. I am the only son of a witch born these thousand years. My mother is one of the Mysterious Three who rule the witches, last remnant of the Council. Fitz was made by that Council, long ago, as a weapon made to fight malignant gods. The more recent unwanted child became a weapon too, puppet and boy flung out to do our duty in the world. A duty that has carried me here . . . to my great regret.”

No answer came to this bubbling, blood-infused speech. Hereward looked across at Jessaye and saw that her chest no longer rose and fell, and that there was a dark puddle beneath her that was still spreading, a tide of blood advancing toward him.

He touched the hilt of the dagger in his side, and coughed, and the pain of both things was almost too much to bear; but he only screamed a little, and made it worse by standing up and staggering to the wall to place his back against it. There were still two guards somewhere, and Fitz was surprisingly vulnerable if he was surprised. Or he might be wounded too, from the struggle with the god.

Minutes or perhaps a longer time passed, and Hereward’s mind wandered and, in wandering, left his body too long. It slid down the wall to the ground and his blood began to mingle with that of Jessaye, and the others who lay on the floor of a god’s antechamber turned slaughterhouse.

Then there was pain again, and Hereward’s mind jolted back into his body, in time to make his mouth whimper and his eyes blink at a light that was a colour he didn’t know, and there was Mister Fitz leaning over him and the dagger wasn’t in his side anymore and there was no bloody froth upon his lips. There was still pain. Constant, piercing pain, coming in waves and never subsiding. It stayed with him, uppermost in his thoughts, even as he became dimly aware that he was upright and walking, his legs moving under a direction not his own.

Except that very soon he was lying down again, and Fitz was cross.

“You have to get back up, Hereward.”

“I’m tired, Fitzie . . . can’t I rest for a little longer?”

“No. Get up.”

“Are we going home?”

“No, Hereward. You know we can’t go home. We must go onward.”

“Onward? Where?”

“Never mind now. Keep walking. Do you see our mounts?”

“Yes . . . but we will never . . . never make it out the gate . . .”

“We will, Hereward . . . leave it to me. Here, I will help you up. Are you steady enough?”

“I will . . . stay on. Fitz . . .”

“Yes, Hereward.”

“Don’t . . . don’t kill them all.”

If Fitz answered, Hereward didn’t hear, as he faded out of the world for a few seconds. When the world nauseatingly shivered back into sight and hearing, the puppet was nowhere in sight and the two battlemounts were already loping toward the gate, though the leading steed had no rider.

They did not pause at the wall. Though it was past midnight, the gate was open, and the guards who might have barred the way were nowhere to be seen, though there were strange splashes of colour upon the earth where they might have stood. There were no guards beyond the gate, on the earthwork bastion either, the only sign of their prior existence a half-melted belt buckle still red with heat.

To Hereward’s dim eyes, the city’s defences might as well be deserted, and nothing prevented the battlemounts continuing to lope, out into the warm autumn night.

The leading battlemount finally slowed and stopped a mile beyond the town, at the corner of a lemon grove, its hundreds of trees so laden with yellow fruit they scented the air with a sharp, clean tang that helped bring Hereward closer to full consciousness. Even so, he lacked the strength to shorten the chain of his own mount, but it stopped by its companion without urging.

Fitz swung down from the outlying branch of a lemon tree, onto his saddle, without spilling any of the fruit piled high in his upturned hat.

“We will ride on in a moment. But when we can, I shall make a lemon salve and a soothing drink.”

Hereward nodded, finding himself unable to speak. Despite Fitz’s repairing sorceries, the wound in his side was still very painful, and he was weak from loss of blood, but neither thing choked his voice. He was made quiet by a cold melancholy that held him tight, coupled with a feeling of terrible loss, the loss of some future, never-to-be happiness that had gone forever.

“I suppose we must head for Fort Yarz,” mused Fitz. “It is the closest likely place for employment. There is always some trouble there, though I believe the Gebrak tribes have been largely quiet this past year.”

Hereward tried to speak again, and at last found a croak that had some resemblance to a voice.

“No. I am tired of war. Find us somewhere peaceful, where I can rest.”

Fitz hopped across to perch on the neck of Hereward’s mount and faced the knight, his blue eyes brighter than the moonlight.

“I will try, Hereward. But as you ruminated earlier, the world is as it is, and we are what we were made to be. Even should we find somewhere that seems at peace, I suspect it will not stay so, should we remain. Remember Jeminero.”

“Aye.” Hereward sighed. He straightened up just a little and took up the chains, as Fitz jumped to his own saddle. “I remember.”

“Fort Yarz?” asked Fitz.

Hereward nodded, and slapped the chain, urging his battlemount forward. As it stretched into its stride, the lemons began to fall from the trees in the orchard, playing the soft drumbeat of a funerary march, the first sign of the passing from the world of the god of Shûme.

Illustrated by Jessica Douglas