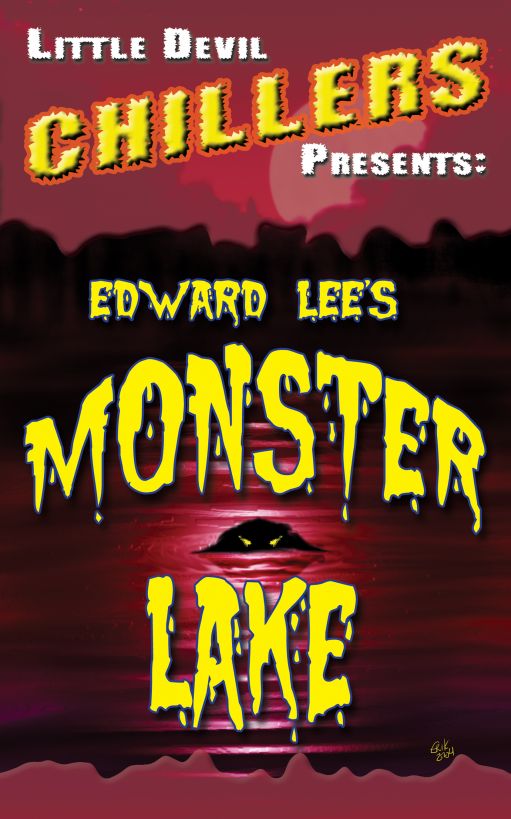

Monster Lake

by Edward Lee

This book is for readers ages 8-12.

— | — | —

Monster Lake © 2005 by Edward Lee

— | — | —

DEDICATION: This book is for Audrey Craker. Perhaps one day I'll write The Little Girl Who Was A Skeleton By Day. Oh, and don't forget what redundant means.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The author would like to thank Taylor Bartscht for much needed editorial consultation. Further, I must acknowledge the swamp behind my grandmother's house in Pound Ridge, New York, which was full of green muck...a far-reaching inspiration.

— | — | —

Prologue

It’s nighttime…

The lake is still, like a black crystal mirror. Fireflies hover over the water, reflecting swarms of green-glowing dots. Bullfrogs and toads hop about at the water’s edge; salamanders climb sluggishly over rocks.

And the moon hangs low over the trees…

The night is teeming with sounds. Crickets and peepers pipe their throbbing chorus. Nightbirds caw, and big white-faced owls hoot from high in the trees. And if you listen carefully, you can even hear the distant titters of bats.

But then—

Suddenly, the woods turn dead silent.

The nightbirds fly away. The bullfrogs and toads scamper to hide…

And the still surface of the lake begins to churn.

From the water, the hideous thing rises, its huge black eyes never blinking, its mouth crammed with rows of razor-sharp teeth that glitter like bits of broken glass in the moonlight.

But what is the thing? It’s big, tall as a man, with a wide head and a pitted, bumpy face.

Not an animal at all but a creature, a monster—

And it’s coming up out of the water now, looking for something.

Maybe it’s looking for you…

Monster Lake

“Ter-ri!” Patricia complained. The shuttlecock whizzed past her as she rushed to swing her racket and missed. “Don’t serve so hard!”

“Sorry,” Terri replied. She knew she was a good badminton player; her only problem was finding someone good enough to practice against. And here, in Devonsville, there weren’t many kids her own age. “Let’s just volley, okay?” she suggested, trying to make the game a little easier for Patricia.

“Yeah, that’d be better. I’m nowhere near as good as you.”

It was a beautiful summer day, a cloudless blue sky, birds chirping high in the trees around Terri’s house. She and Patricia Kennedy had only met a few weeks ago, when the Kennedys had first moved here, but they’d become best friends fast. They were both the same age—twelve—and they both liked a lot of the same things, like Game Boy, The Simpsons, and nachos with cheese and salsa. And, of course, they both liked to play badminton—or lawn tennis, as Terri’s Uncle Chuck like to call it—but Patricia wasn’t very good. It didn’t matter. They’d been hanging out together most every day since Patricia had moved to Devonsville.

Patricia’s long blond hair swayed as she rose on her tiptoes to serve. Poink! the shuttlecock went, then sailed across the net. Terri’s hair was just as long but a shiny dark chestnut color, and she had emerald-green eyes instead of blue, like Patricia’s. She easily returned her friend’s serve, and they volleyed the shuttlecock back and forth for several minutes. Terri could tell that Patricia was trying hard to beat her but—poink-poink-poink-poink—Terri was able to return all of Patrica’s hits back hardly without even working up a sweat. Eventually, Patricia missed and declared, “All right, already! You win!”

Terri smiled to herself. “It’s getting hot. Let’s go around to the back of the house and get a drink from the hose.”

“Good idea,” Patricia agreed, wiping her brow.

They returned the badminton rackets to the side shed, then headed for the house, a nice, three-bedroom ranch with cedar shingles. “You’re really good at badminton,” Patricia complimented. “Who taught you to play?”

Terri’s smile faded. “My Dad. He was going to start teaching me to play tennis soon, too, so that once I get to high school, I’d be good enough for the team. Dad and I would do lots of stuff, until…”

Patricia kicked at a dandelion puff. “Oh, you mean before he and your Mom got divorced?”

“Yeah,” Terri sadly replied. These days lots of kids’ parents got divorced. Terri never quite understood it until Uncle Chuck explained that sometimes people changed over time, and they didn’t agree on things, or see things the same way. “Sometimes parents grow apart,” her uncle had explained, “and they can’t get along anymore.” But that was the weirder part, because Terri could never remember a time when her Mom and Dad didn’t get along.

She could only hope that one day her parents would get back together…

And there was one thing she’d noticed very clearly: that since the divorce, her mother had started acting really weird, and Uncle Chuck too.

“How do you like Devonsville so far?” Terri asked, to get her mind off the subject.

“Oh, it’s okay. It’s a lot different from the city, where we used to live. The city was real crowded and had lots of smog. Devonsville is so pretty,” Patricia observed, looking around now at the healthy, green lawn, the clear sky, and the woods behind Terri’s house.

“We used to live in the city too,” Terri said. “But I like it here much better.”

“What’s school like?”

“It’s okay. Not as many kids as the city, but everyone’s nicer here.”

Patricia grinned wickedly. “Any cute boys?”

“There are some,” Terri answered. And then her thoughts drifted. Yes, she was at the age now where she’d be getting interested in boys. She even knew some girls at school who were going steady! And there were a few boys, she knew, who were interested in her, like Matt Slattery, who was on the eighth-grade wrestling team; and Marty Cadeaux, who was fat but nice and asked her to the school dance once. And Terri knew she must be pretty, because if she weren’t, why would these boys be interested in her? It was nice to know that boys liked her, and that she could have a boyfriend if she wanted, but it just seemed that…

Terri frowned at herself as she and Patricia cut across the big yard.

It seemed that she’d lost interest in those kinds of things since her parents had gotten divorced.

And there was still one more weird thing. Terri knew that when parents got divorced, the father usually moved away—like Terri’s father had—but she also knew there was something called visitation rights, so that the father could visit on weekends.

But my father’s been gone all summer, she reflected; for months, and he’s never visited me on the weekends. And this made Terri even more sad.

Maybe he doesn’t want to visit me…

But Terri couldn’t even think about that.

“What grade are you in?” Patricia asked, the sun shining brightly in her long blond hair.

“Seventh—well, I’ll be in the eighth when school starts up after the summer.”

“But you’re only twelve!”

“I know. I got moved up a grade.”

“You must be real smart,” Patricia offered, along with a hint of jealousy.

“I just study hard,” Terri admitted. “My Mom and Dad always taught me to study hard…”

And then the thoughts returned. Mom and Dad…

Dad…

Suddenly, Terri felt really depressed, like there was a big hole where her heart should be.

Will I ever see my father again? she wondered, fighting to hold back tears.

««—»»

“Ooo, that’s good!” Patricia remarked.

Cool, clear, fresh water gushed from the garden hose as Terri and Patricia leaned over and took turns drinking. They laughed, frolicking, as they sprayed each other. The cool water felt wonderful in the hot sun.

Then: “Look!” Patricia exclaimed.

A big, bumpy toad looked up at them, sitting in a small corner of shade cast by the back porch steps. It had big black eyes with gold irises.

“That’s the biggest toad I’ve ever seen!” Patricia observed.

“Oh, there’re bigger ones,” Terri said.

“You’re kidding!”

“Yep. I’ve seen toads three times as big as that one, and bullfrogs even bigger. They’re all over the place.”

Patricia suddenly looked flustered. “I wonder why we don’t have any toads and frogs in our yard.”

“That’s because we have a lake.” Terri pointed to the tall trees at the back of the house, where a little path formed. “See that trail?”

Squinting, Patricia nodded.

“It leads down to the lake,” Terri went on. “It’s not a very big lake, but it’s neat. That’s where all the toads and frogs come from. There’re fish in it too, and big salamanders.”

Suddenly, excitement lit up Patricia’s face. “Let’s go! I’ve never even seen a salamander, except in books. Come on!”

Terri hesitated. “No, we better not. I’m not allowed.”

“Why not?” Patricia objected. “You’ve got a lake behind your house but you’re not allowed to go see it?”

“Well, I’m allowed but only if my Mom’s with me, or my Uncle Chuck. We’ll go soon though, I promise.”

Of course, that might be a hard promise to keep since, these days, both her mother and Uncle Chuck frequently worked late into the night.

“I can’t wait,” Patricia enthused. “I can’t wait to see it!”

“You will.” Then Terri leaned over, and—

“No, don’t!” Patricia shrilled.

—and picked up the big toad by the porch steps.

“You’re not supposed to touch toads, Terri,” Patricia warned. “They’ll give you warts.”

Terri scoffed. “No they don’t. I’ve picked up lots of toads and I’ve never gotten a wart. Toads can’t give you warts; that’s just an old wive’s tale.”

“How do you know?”

“My Dad told me. He’s a zoologist.”

“A zoologist? What’s that?”

“It’s someone who studies animals. There’s a zoology lab not too far from here, where scientists do research. That’s where my Dad worked, until…”

“Until what?”

Terri’s suntanned shoulders slumped in despair. Here was that bad subject again. “Until he and my Mom got divorced, and he moved away.”

“Oh,” Patricia said.

And this was something Terri didn’t quite understand. She knew what divorce was, but she didn’t see why a divorced person would stop working at the place they usually worked. One day, a couple of weeks after the divorce, Terri asked her Mom if she could call her father at the zoology lab. “He doesn’t work there anymore, honey,” Mrs. Bennet sadly told her. “He moved away.” And Uncle Chuck later told her the same thing. “Sometimes when people get divorced, Terri, they move far away.”

Far away, the words repeated now in her mind…they move far away…

Just one more thing that made her feel sad.

“But that must’ve been neat, having a Dad who studied animals,” Patricia said, not realizing Terri’s constant sadness over the topic.

“Yeah,” Terri agreed. “It was. I guess it runs in the family. My mother has a zoology degree, and she works at the same lab that my Dad used to work at. And my Uncle Chuck teaches biology at Devonsville Junior High. I’m going to be a zoologist too, when I’m an adult.”

“Sounds like a neat job.” Then Patricia leaned forward, looking at the big toad that Terri gently grasped behind by its legs. Its big eyes, like black marbles, never blinked. Loose white skin under its throat fluttered back and forth. Then—

Terri squealed and quickly put the toad back down on the ground.

“What happened?” Patricia asked.

Terri laughed, then turned the garden hose back on to wash her hands.

“It peed in my hand!” she said.

««—»»

Terri washed her hands off again, with water and soap, once they got into the house.

“What a great house,” Patricia noticed, her eyes glancing around.

“Yeah, it is nice,” Terri replied half-heartedly. It was a nice house, with big spacious rooms, but…

More bad feelings.

It seemed that anytime she looked at anything—anywhere in the house—she was again grimly reminded of her father. Right now, for instance, here in the kitchen. It reminded her of all the times she and her father and mother had had breakfast together in the mornings, before the school bus came and picked her up at the bus stop down the street. She looked at the microwave oven and remembered the time her father had taught her how to use it, how to set the digital timer that beeped, how to adjust the heat setting. Next, she looked at the big four-burner range and recalled how her father liked to make bacon and cheese omelets for the whole family every Saturday morning. And they were great omelets.

“It seems so empty all the time now,” Terri said without really thinking.

“Well, maybe your Dad will come back someday,” Patricia offered. “Maybe he and your Mom will get back together.”

“I hope so…”

By now, Patricia could probably guess that this was not Terri’s favorite thing to talk about. “But your Uncle Chuck lives here too, doesn’t he?”

“Yeah, he has since my Dad left. He drives my Mom to work every morning, and picks her up—that’s where he is now. And he looks after me during the day, when school’s out for vacation.”

thunk, thunk

The sound of car doors closing.

“Here they come now,” Patricia said, glancing out the window which she could see from the dining room.

Terri glanced out too, and sure enough, there was the car in the driveway, with her Mom and Uncle Chuck getting out.

“What are all those things they’re carrying?” Patricia asked.

But this was a familiar sight to Terri. Both her mother and Uncle Chuck carried two big black briefcases each as they trundled up the driveway toward the front door.

“Mom has to bring a lot of work home from the zoology lab,” Terri eventually answered. “She only used to work part-time, but since the divorce she works every weekday.”

“Well,” Patricia considered, “at least she’s home on the weekends, so you can do stuff with her then.”

“Not really. She has so much work from the lab, she has to work on it at home on Saturdays and Sundays now.”

“Oh, that’s a bummer.”

“Hi, Mom, hi, Uncle Chuck,” Terri greeted when they both walked in.

“Hi, kids,” Terri’s mother replied, smiling in her dark pumpkin-orange business dress.

“Who’s this?” Uncle Chuck asked when he saw Patricia.

“This is my friend, Patricia,” Terri introduced. “This is my Uncle Chuck.”

“Hi,” Patricia said.

“Pleased to meet you, Patricia,” Uncle Chuck returned the greeting. Uncle Chuck was tall and thin, with short dark hair and a nice smile.

“Patricia will be in seventh grade when school starts,” Terri said. “I was just telling her that she’ll have you as her biology teacher.”

“That’s great,” Uncle Chuck said. “So you must be new in town?”

Patricia nodded. “I only just moved to Devonsville a few weeks ago. It’s a really nice town.”

“So what have you girls been up to?” Terri’s mother asked.

“We were playing badminton while Uncle Chuck was picking you up at work,” Terri said.

“And we saw this absolutely huge toad in the back yard,” Patricia cut in.

“We do seem to have a lot of toads around here,” Terri’s mother added. “They’re all over the place.”

“Because you’re so close to the lake, right?” Patricia asked.

Terri’s Mom and Uncle Chuck traded strange glances at Patricia’s remark. And this just reminded Terri how strange overall her mother and Uncle Chuck had been acting lately.

“Well, yes,” Terri’s mother eventually answered Patricia.

But Uncle Chuck looked a little disturbed. “Uh, girls? You weren’t at the lake today, were you?”

“No, Uncle Chuck,” Terri answered. “You said kids shouldn’t go there unless an adult’s around.”

“That’s right, hon. Because lakes can be dangerous. You could fall in, plus, you know, it could be polluted.”

Terri’s brow rose. She’d seen the lake lots of times, and it didn’t look polluted to her. The water was crystal clear, and she’d never seen any garbage or anything floating in it. This seemed like a strange thing for Uncle Chuck to say.

“But I told Patricia that you or Mom would take us down there and show it to us sometime,” Terri said, remembering her promise.

And again—

—Terri’s mother and Uncle Chuck traded weird glances.

“Well, sure, honey,” her Mom said. “We can do that sometime.”

“But not soon,” Uncle Chuck said. “It’s too hot to go down there during the summer. There’re lots of bugs and mosquitoes and things. And snakes.”

“Snakes!” Patricia exclaimed. “I’ve never seen a real snake.”

But Terri raised her brow again.

I’ve never seen any snakes at the lake, she realized.

It almost sounded like Uncle Chuck was making it up, so Terri and Patricia wouldn’t be tempted to go down there on their own…

Hmmm, she wondered. Then she said, “Are we going to get pizza tonight, Mom? Like you said we could this morning?”

“Oh, honey, I’m sorry,” her mother apologized. “I hope you’re not too disappointed, but I’ve got so much work to do tonight, I don’t have time, and neither does Uncle Chuck.”

I knew it, Terri thought. Same old story.

“We’ll get pizza soon, though,” Uncle Chuck said.

“Maybe Pamela would like to stay for dinner,” Terri’s mother suggested.

“It’s not Pamela, Mom. It’s Patricia,” Terri corrected.

“Oh, yes, of course. I’m sorry, Patricia. Anyway, why don’t you cook some TV dinners for yourselves in the microwave?”

“But aren’t you and Uncle Chuck going to eat?” Terri asked.

“Later,” Uncle Chuck said, and held up the briefcases. “Right now your mother and I have to get to work.”

“Okay,” Terri glumly replied.

“Nice meeting you, Patricia,” Uncle Chuck said as he and Terri’s Mom headed for the back door.

“Bye,” Patricia said.

Then the back sliding glass door slid closed, and they were gone.

Patricia squinted after them.

“You want to stay for dinner?” Terri asked, but it was more for distraction than anything else. She could guess what Patricia was thinking. “We’ve got all kinds of good TV dinners.” She opened the freezer and showed her. “Fish fillets, enchiladas, sliced turkey and gravy. They’re pretty good.”

“Well, okay. But I’ve got to call my parents first.”

“The phone’s right over there,” Terri said, pointing to the end of the kitchen counter.

Patricia dialed her number, then asked if she could stay. Then she hung up, looking weird.

“Did they say you can stay for dinner?” Terri asked.

“Uh, yeah, I can stay.”

“Then why do you look so weird all of a sudden?”

“Well…” She glanced out the back sliding-glass door.

“What is it?”

Patricia turned back to her.

“Your Uncle Chuck said that he and your mother have lots of work to do?”

“Yeah,” Terri said. “They have lots of work almost every night, like I said.”

“You mean like office work, right? From the zoology lab where your Mom works?”

“Yeah.”

Patricia glanced back out the door again. “If they’ve got office work to do, how come they’re walking across the back yard with their briefcases? Toward the lake?”

««—»»

The microwave beeped, and Terri, wearing pot-holder mittens shaped like owls, took the food out. “Well,” she said, to answer Patricia’s question, “remember that trail I showed you, that leads to the lake?”

“Yeah.”

“There’s also a little boathouse down there, right on the water—”

“Wow!” Patricia said excitedly. “You have a boat too?”

“It’s just a little motorboat, we’ve never even used it because it needs to be fixed. But my Dad turned the boathouse into an office.”

“An office? Why?”

Terri shrugged as they sat down at the kitchen table to eat their TV dinners. “I told you, he and my Mom are zoologists, and I guess they wanted their office to be close to the lake so they could study the animals there.”

“Like the frogs and toads and things?”

“Yeah.”

“And the snakes!”

Terri paused. “Well, I don’t think there really are any snakes in the lake.”

“But your Uncle Chuck said there were.”

“Yeah, but he may have been making that up so you and I wouldn’t be tempted to go down there by ourselves. I mean, I’ve never seen any snakes around here… Anyway, that’s why my Mom and Uncle Chuck were going out back. They do their work in the boathouse.”

Patricia turned her fork idly in her cheese enchiladas. “But isn’t that—you know—kind of weird?”

“What?”

“Turning a boathouse into an office?”

Terri thought about that. Sure, her mother was a zoologist—just like her father had been—and the boathouse was close to the lake. But the work she brought home every night came from the laboratory she worked at just outside of town. What could it have to do with the lake?

Yeah, she finally had to admit to herself. I guess it is kind of weird. And that thought only reminded her more of how weird her mother had been acting over the past few months, and Uncle Chuck too.

“And another thing,” Patricia went on. “Did you see the weird way your mother and your Uncle Chuck looked at each other whenever you mentioned the lake?”

Terri had noticed that too, and she couldn’t deny it. “You’re right,” she agreed. “It was almost like they were…hiding something from us.”

“That’s right,” Patricia agreed. “And it must have something to do with the lake or the boathouse.”

Terri couldn’t imagine what it could be. What could they possibly want to hide? she wondered.

Then Patricia asked, “Have you ever been in the boathouse?”

“Yeah, a few times, back when my father lived here.”

“What was it like?”

“Well, like I told you, my father turned it into an office, or I should say he turned the front room into an office.”

“You mean there are other rooms?”

“A few,” Terri recalled.

“What was in them?”

Terri hesitated. “I don’t really know,” she confessed. “Mom and Dad told me to never go into any of the other rooms.”

Patricia held her hands out. “See, there’s another weird thing. Whatever it is they’re hiding, it must be in those other rooms.”

Terri hadn’t considered that. But she had to admit: Patricia was right. There did seem to be an awful lot of weird things going on lately.

Patricia leaned over the kitchen table, lowered her voice. “Don’t you want to know what it is? What they’re hiding?”

“Well, yes,” Terri agreed.

“Well, then…”

“Well, then what?” But this was a phony question on Terri’s part, because she already had a pretty good idea what Patricia was going to suggest.

“Why don’t we sneak down there?” Patricia said.

“We can’t!” Terri exclaimed. “We’re not allowed. If I took you down there without my Mom’s permission, I’d get into all kinds of trouble!”

Patricia grinned like a cunning cat. “They’ll never know,” she said. “We’ll go in the morning, when your Uncle Chuck is taking your Mom to work.”

Terri thought about it.

We really shouldn’t, she thought.

But—

“Okay,” she said. “That’s just what we’ll do.”

««—»»

The best thing about summer vacation was that she could stay up a little later and watch TV. Terri preferred the Disney Channel and the National Geographic shows about nature and wildlife and animals in other countries, and, of course, The Simpsons. But tonight, she found it hard to pay attention to her favorite shows. Her mind felt like it was somewhere else, and she thought she knew why…

Patricia had been right. Terri’s mother and Uncle Chuck were acting weird. Those strange, foreboding glances they’d exchanged, Uncle Chuck’s lie about snakes, and then the entire business with the boathouse. Terri supposed she’d known something was wrong all along, but she’d never wanted to admit it to herself. It was hard enough that her father and mother were divorced, and that she hadn’t seen her father for so long—plus her fear that she’d never see him again. Sometimes, when things were too hard to cope with, people would overlook the obvious. There were a lot of strange things going on recently; Terri was surprised that it took her this long to realize it.

“Terri?” Uncle Chuck stuck his head in the rec room, where Terri lay on the floor before the TV. He was still wearing the same clothes he wore when he’d brought Terri’s mother home from work, and he gripped one of the big black briefcases.

“Bedtime,” he said.

Generally, Terri would’ve complained a little, but tonight she was unusually tired. She straggled up to her feet, and then noticed with some surprise that it was past eleven o’clock.

“Has Mom already gone to bed?” she inquired.

“Not yet,” Uncle Chuck answered. He looked tired too, droopy. “She’s still working in her office.”

Her office, Terri thought to herself. You mean the boathouse…

And whenever she thought of the boathouse, she remembered the rooms in it that her mother and father had forbidden her to ever enter.

“But she’ll be up soon,” Uncle Chuck continued. “Sweet dreams.”

“Goodnight,” Terri said.

Uncle Chuck, still toting his briefcase, disappeared down the hall. Terri retreated to her own room, and put on her favorite soft-pink nightgown. Then she climbed into bed, lay back in the pillows, and—

—listened.

She almost always kept her bedroom window open during the summer; summer nights in Devonsville were breezy and cool, unlike the summer days. It was nice to listen to the crickets peep at night, a steady, gentle throbbing sound that always lulled her to sleep. But tonight she felt fidgety and restless. And the nightsounds coming in through the window sounded…different.

But how so?

They sounded louder and faster. They sounded, somehow…

Menacing.

But why should she think that?

They’re just crickets and little tree frogs, she realized.

She was being silly, she knew.

Her hand reached up then, paused, and turned off the light.

Darkness jumped into the room, and the nightsounds seemed to grow even louder and more etchy. She’d never been afraid of the dark before, not even when she was little. Only babies are scared of the dark, she told herself. Unless—

Unless…what?

Unless there’s really something in the dark to be afraid of, Terri thought.

She drifted in and out of sleep, tossing and turning. Every so often she’d wake up and, for some reason, look at her bedroom window, which was full of moonlight. The nightsounds throbbed on without letting up.

She tried to think about fun things. Like about when school started up again next month, about her lessons, and about boys. She hoped Matt Slattery didn’t have a girlfriend by then, and Marty Cadeaux too, even though he was kind of fat. In three or four years, she’d be old enough to go on real dates, and that would be fun…

But the more she tried to think of these things, the more she realized she was forcing herself to do so.

And the more she realized—

She was scared.

But of what, she couldn’t guess.

And that’s when she heard the sound.

Not the typical nightsounds. Not the crickets and peepers and the owls hooting.

This sound was different.

It was coming from her open window, and as she lay wide-eyed in the dark, she eventually figured out just exactly what the sound was:

Footsteps.

««—»»

Footsteps! Terri thought.

And right outside!

At first, she wanted to call out, but then she thought, Don’t be a baby, Terri. Maybe you just dreamed the sound.

But still…

She had to know.

Very slowly, then, she slid out from underneath the sheets and climbed out of bed. The only light was moonlight streaming in from the window, and the window was several yards away. Her bare feet padded across the carpet, through the dark. When she reached the window, she went down onto her knees. Her hands reached out. Her fingers gripped the sill. Then, very slowly, she inched her face toward the window screen, and looked out…

At first, she didn’t see much. Just the back yard, and the dark splotches that were the tall trees where the woods began. Between some of the trees she saw weird green dots that seemed to be glowing… Fireflies, she realized. Lightning bugs.

Then, as her eyes grew accustomed to the dark, she noticed—

Jeeze!

Strange shapes seemed to be jerking about in the back yard. She knew at once that they were toads, hopping around, looking for bugs. But—

They’re huge, she saw.

Her eyes must be playing tricks on her. She’d seen lots of big toads and frogs in the yard before, but never this big!

They were as big as puppies!

Then—

From the bushes, a baby rabbit hopped into the yard, then stopped to nibble some grass. Its ears poked up, its little nose twitched. But Terri’s breath caught in her chest, and she nearly squealed out loud when she saw what happened next.

One of the huge toads hopped toward the rabbit, seeming to move with astonishing quickness, its heavy rear legs flexing mightily with each hop. Terri knew that toads didn’t eat rabbits, not even big ones like this—toads only ate small insects, like flies and moths and beetles. But what frightened her was this:

In the streaming moonlight, the toad’s wide jaw snapped open, and sparkling inside its mouth were two rows of sharp, pointed teeth!

It’s going to eat the rabbit! Terri’s thoughts screamed in her head.

The hideous toad leapt forward several more times, its razor-toothed jaw opening wider. Each leap seemed a yard long—

Oh, no! Terri thought in sheer dread.

But just as the toad would pounce on its unsuspecting prey, the baby rabbit finally took notice, its head jerking aside, and it scampered safely away just in the nick of time.

Terri sighed in relief. It would have been horrible to have to watch that toad eat the rabbit. But then she stopped to think—

None of it made sense, it was impossible. One thing she was sure of: toads, no matter how big they were, didn’t eat animals and they didn’t have long, sharp, pointed teeth!

Am I dreaming? she considered again. She must be, to have witnessed such a thing. Outside, everything looked unreal, the grass like spikes of ice in the moonlight, the blinking green swirls of the fireflies, the cramped shadows between the trees, not to mention the monstrously large toads. But then she remembered the reason she’d gone to look out the window in the first place.

The footsteps, she recalled. I heard footsteps in the back yard. I’m sure I did. And they sounded like they were coming up from the lake…

Terri strained her vision then, focusing her eyes through the window screen, toward the rear corner of the yard.

crunch, crunch

She was right. There was the sound again, and they were footsteps.

crunch, crunch

There could be no denying it. Someone was indeed walking up the gravel path from the lake to the house.

And the sound was much louder now, which meant that whoever was walking—they were getting closer.

Terri bit her lower lip as she stared on, gripping the window sill. Only a moment later, a figure appeared at the entrance to the trail.

Who could it be?

She glanced warily at the lighted, digital clock on her nightstand—

It was almost 4:30 in the morning!

Terri’s breath grew thin. Her heart beat faster as the figure came out of the crisp shadows thrown by the trees and—

crunch, crunch

—stepped into the moonlight, fully into view.

It’s…my mother, Terri realized in shock. She’s been down at the boathouse all night…

««—»»

All night, Terri thought again the next morning at breakfast. What could her mother be working on that was so important she had to stay up till past 4:30 a.m.? And Terri could tell. Right now, coming into the kitchen, her mother looked exhausted, with drooping shoulders and dark circles under her eyes.

“Good morning, dear,” she said groggily.

“Hi, Mom,” Terri said. “You sure look tired.”

“I am, I was up late. Working.”

You’re not kidding you were up late! Terri agreed in her own thoughts. Late as in 4:30 in the morning!

But Terri declined to actually comment on what she’d seen last night. By now, she wasn’t even sure what she’d seen. The whole thing was so visually unreal—maybe she really had dreamed a lot of it. After all, she thought she’d seen a giant toad try to eat a rabbit! And she knew that was impossible. Maybe she’d only dreamed seeing her mother coming up from the trail to the lake so late…

But then her mother commented:

“God, I’m so tired. I could fall asleep right here at the table…”

Terri looked at her, and that set her to thinking. If she’d only dreamed seeing her mother coming up from the lake, why would she be so tired?

I must not have dreamed it, Terri concluded. And if I didn’t dream that, then I must not have dreamed about the toad either. The toad…with teeth…

“Breakfast is ready!” Uncle Chuck announced, placing a large tray down on the kitchen table. Toast, marmalade, assorted jellies. Terri was grateful for the distraction; she felt so confused about things right now that she didn’t want to think about them.

She nibbled at her toast, remembering times not so long ago when breakfast had been a big, happy family affair full of conversation and laughter. Back when Dad was still here, she thought. Now, things were so different. Breakfast, like most meals they had together, were fast, thrown together at the last minute, and over before anyone really had a chance to talk. Her mother was so busy now, always in a rush to go to work, and even when she was home, most of her time was spent—

In the boathouse, Terri thought.

“Well, we’ve got to go now, Terri,” her uncle said after only eating one piece of toast. “I’ve got to take your Mom to work.”

“Have a good day, honey,” her mother said, and leaned over to give Terri a kiss.

“’Bye,” Terri said.

Her mother and Uncle Chuck left, as usual, in a rush. Terri glumly washed the few dishes they’d used, and put them away. She knew she shouldn’t be selfish—after all, the reason her mother had to work so much was because she had to pay the bills. At least Uncle Chuck was helping her out. But—

Things were so much better when Dad was here, she thought. There just didn’t seem to be anything to look forward to anymore.

squeak

Terri glanced over her shoulder. She swore she’d heard a sound, a faint squeak. Like…

Like someone standing in the foyer, she realized just then, because the foyer’s hardwood floor always squeaked the same way. But she’d heard her mother and Uncle Chuck leave the house and close the door behind them, and she’d heard the car engine start and the car drive off, so she knew they hadn’t come back in to get something they’d forgotten.

squeak

There it was again!

Terri’s eyes widened in the kitchen. She could feel her heart racing. It’s nothing, she tried to tell herself. It’s just a house noise. Stop acting like a baby!

So, to prove to herself that no one was there, she boldly left the kitchen and marched right into the foyer, and—

Screamed!

Because the second she’d stepped into the foyer, someone grabbed her from behind—

««—»»

“Patricia!” Terri yelled after spinning around.

Patricia laughed hysterically, standing in the open coat closet in the foyer. “Did I scare you?”

“Yes!” Terri was outraged. “What, you just walked right in the house without even knocking?”

“I was coming up the sidewalk when your Mom and Uncle Chuck were leaving,” Patricia told her, still laughing. “They said I could come in.”

“Well, don’t ever do that again!”

“Chill out, will you, Terri?” Patricia said. “Jeeze, it was just a joke. Can’t you take a joke?”

“Yes, Patricia,” Terri sternly replied. “I can take a joke. But I don’t like to be scared half to death!”

“All right, already.”

But as the scare wore off, Terri realized she was over-reacting, and she knew why. She was still tense from last night, from the restless sleep and the dream she’d had, and, of course, seeing her mother coming up from the lake at 4:30 in the morning. And again she felt immediately confused. She knew she hadn’t dreamed the part about her mother coming up from the lake, but what about the rest? The giant bump-skinned toad with the sharp, pointed teeth…

I must have dreamed that, she decided.

“Well?” Patricia said.

“Well what?”

“Are we going or not?”

Terri’s mind felt in a fog. “Going where?” she asked.

Patricia rolled her eyes. “Don’t you remember what we planned yesterday? We’re supposed to go down to the lake.”

««—»»

That’s right, Terri recalled. In all her anxiety over the dream—or whatever it had been—she’d completely forgotten. Yesterday, they’d planned to sneak down to the lake while Uncle Chuck was driving her mother to work. She still didn’t feel good about it—she knew she’d be in big trouble if she got caught—but, still…

She really wanted to go.

“All right, let’s go,” she said. “But we have to be quick. We can’t hang around down there for too long.”

They went out the back sliding door and crossed the back yard, both in sneakers, shorts, and colorful day-glo T-shirts. The morning was sunny and bright. Sunlight shined on the back yard grass, and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky.

“How long does it take your uncle to drive your Mom to work?” Patricia asked mindfully.

“It’s about fifteen minutes each way.”

“So that gives us a half hour.”

“Yeah, but we better make it twenty minutes, just to be safe,” Terri suggested. She didn’t want to take any chances; if her mother or Uncle Chuck knew she’d disobeyed them, and gone down to the lake, she’d be grounded for a month! No TV, no badminton, no nothing!

They crunched down the gravel path behind the house, and descended into the woods. Suddenly, the hot, bright morning darkened and turned cool; the dense trees of the woods shaded the path—Terri imagined herself walking down a tunnel.

Patricia, as they walked, was glancing worriedly around.

“What’s wrong?” Terri asked.

“I’m keeping an eye out for snakes.”

Terri smiled to herself. There she goes again with her snakes. Terri wasn’t worried at all about snakes—she knew there really weren’t any around here—but there were a few things she was worried about, and the boathouse was one of them. She still felt mystified as to why her mother would be working in the boathouse so late. Terri herself had only been in the boathouse a few times, and only in the front room, which her father had turned into an office. But there were other rooms, she knew, rooms she hadn’t seen, rooms that her parents had forbidden her to enter.

And I’m going to find out what’s in them, she determined to herself.

Because she had the strongest suspicion that those other rooms had something to do with the strange way her mother had been acting over the past few months.

“It sure is pretty down here,” Patricia said.

“Yeah, I know.”

“And look at all the flowers between the trees!”

There were indeed many forest flowers all around them, in a variety of tones and colors, plus lots of pretty green ferns and other plants.

“What kind of flowers are these?” Patricia inquired. “Do you know?”

“Not really. I don’t know that much about flowers.”

“Can I pick some of them and take them home?”

“Sure,” Terri said.

Patricia stepped off the path into the woods, scanning for the biggest and prettiest flowers. Then she spotted some bright orange ones, with bright-yellow centers, growing at the base of one of the big, thick-trunked oak trees. She reached toward the flowers to pick them, then flinched, then…

Shrieked at the top of her lungs.

“Patricia!” Terri exclaimed. “What’s wrong?”

Patricia stumbled back out of the brush, and grabbed Terri in trembling fear.

“A snake!” she shouted. “There’s a huge snake right there next to the tree!”

««—»»

Terri’s heart swelled in her chest. A snake! She’d been wrong all along. She and Patricia clung to each other, their faces pale with fear.

“It’s right there!” Patricia wailed, pointing toward the brush at the base of the tree. “See it?”

Terri squinted, trying to focus her eyes. She was looking right at where Patricia was pointing. But—

I don’t see any snake, she thought.

“Where?” she asked. “Where’s the snake?”

“Right there!” Patricia insisted, still pointing. “Can’t you see it? That big, fat gray snake right there next to the orange flowers?”

Terri’s mouth hung open when she saw it. She rolled her eyes and laughed. “Patricia! That’s not a snake! That’s a dead tree branch!”

Patricia stared forward; she didn’t seem to believe it. “No, it’s not! It’s a snake, just like your Uncle Chuck said. It’s a snake, and it might bite us!”

Terri’s laughter continued. “Don’t be a moron, Patricia.” Then she stepped into the brush, reaching down.

“Don’t go in there!” Patricia screamed. “It’ll bite you for sure! It’s probably poisonous!”

Terri boldly picked up the scaly branch and held it up. “See?” she said. “Here’s your snake.” Nothing but an old, dead tree branch. She broke it over her knee and cast it back into the woods.

“Jeeze,” Patricia said, relieved now. “I guess I am a moron. I really thought it was a snake.”

“Well, sometimes your eyes can play tricks on you. You’ll think you’ll see something that’s not really there. It turns out to be something else.”

“I guess so. Like when I was little, sometimes I’d think my blouses hanging in my bedroom closet were really people standing there.”

“Yeah, like that.” But then Terri thought about it. Yes, sometimes the eyes did play tricks on you. Is that what happened last night? she questioned herself. She felt sure now that she hadn’t really seen the big toad with teeth. But what of her mother, walking up the trail from the boathouse at 4:30 in the morning?

Maybe I didn’t really see that, either, she considered. Maybe it was just my eyes playing tricks on me.

She hoped so, at least.

“I feel like an idiot,” Patricia said. “I thought that stupid branch was a snake. Don’t tell anyone, okay?”

“I won’t tell anyone,” Terri promised as they continued down the path. “Everybody’s eyes play tricks on them sometimes. It’s happened to me too.”

“Really? When?”

Last night, Terri thought. But she didn’t want to tell Patricia what she thought she’d seen. Patricia would laugh her head off if Terri told her about the giant toad with teeth trying to eat the rabbit in the yard. “I don’t know,” she said instead. “But it happens to everybody once in a while. It’s no big deal.”

They continued on down the path, their sneakers crunching over the gravel. Little spots of sunlight, shining through the leaves on the trees, seemed to blink at them from above. Along the way they saw lots of birds and mushrooms and many more plants and colorful flowers. Butterflies fluttered around them in the shade, and moths and dragonflies.

And then—

A glare of sunlight shined in their eyes. The lake, Terri realized. Where the trees opened at the end of the path, they could see the water now, and the sun shining brightly on it like a huge mirror.

“Is that it?” Patricia asked excitedly.

“What?” Terri asked, but she already knew the answer to her friend’s question. The brown-shingled building at the very end of the path, propped up over the water on its own pier.

“Is that the boathouse?” Patricia said.

Suddenly, for some reason, a prickling chill ran up Terri’s spine…

“Yeah, that’s it,” she informed. “That’s the boathouse.”

««—»»

“Wow, this is neat!” Patricia exclaimed. They walked up onto the planked pier. If you looked down, you could see the water between the cracks in the planks. And a gentle lapping sound could be heard too: the water at the edge of the lake slapping against the pier posts.

Patricia walked out to the end of the pier, gazing out onto the lake. “This is beautiful. It’s bigger than I thought it would be.”

“It’s not that big,” Terri said. She’d seen much bigger lakes. But it was still a good size.

“Is that your boat?” Patricia asked, pointing down.

“Yeah.” The small boat floated lightly, tied by a thick rope to one of the pier posts. “I’ve never even been out on it.”

“It’s even got a motor!” Patricia noticed. “Do you know how to work it?”

“All I know is you pull that cord there on top of the motor,” Terri said. “But there’re buttons you have to adjust too, and I don’t really know how to do it. There’s something on it called a throttle; you have to set it right first. But I don’t even think it works anymore.”

“How do you know?”

“Well, my Dad told me.”

“Yeah,” Patricia scoffed. “And your Uncle Chuck told you there were snakes all over the place. And all we found were branches. Maybe your Dad told you the boat didn’t work because he didn’t want you to use it.”

Patricia, Terri knew, had a point. It just seemed to her that sometimes grownups said things on purpose that weren’t true, to discourage kids.

“I don’t know,” was all Terri said in response.

“Well, why don’t we try it?”

“What? Riding in the boat?” Terri questioned, astonished.

“Yeah, why not?”

“Because I already told you, my Uncle Chuck’ll be back in a half-hour. Do you have any idea how much trouble I’d get in if he caught us in the boat? I’d get grounded if he even knew we’d come down the path.”

“All right, all right,” Patricia agreed. “But let’s at least look around.”

“Okay.”

They approached the door to the boathouse. Terri was still very curious about what was in there. She knew the front room was just an office, but why would her parents forbid her from ever going in the other rooms? I’m going to find out right now, she decided. Her Mom and Uncle Chuck would never know. What harm could there be in her just looking around real quick?

“All right,” Terri said. “Let’s go in.” And then she put her hand on the doorknob, turned it, and—

“Oh, no!” she exclaimed.

“What’s the matter?” Patricia asked.

Terri looked back at her friend in sheer frustration.

“The door’s locked!” she exclaimed.

««—»»

The wooden door jiggled in its frame but wouldn’t open. Terri could see the lock’s metal bolt between the gap.

“What are we going to do now?” Patricia asked, with more than a little disappointment.

Terri’s eyes thinned. “Well,” she said slowly, thinking. “One time on TV I saw somebody open a locked door with a credit card.”

“A credit card!” Patricia exclaimed. “Where are we going to get a credit card? We’re only twelve! Are you telling me you have a credit card?”

“No,” Terri said. Of course, she didn’t have a credit card; only adults had those. “But I’ve got a library card.”

Patricia watched with amazement as Terri withdrew her plastic covered Devonsville Library card and slipped it in between the edge of the door and the doorframe. Very carefully, she worked the edge of the card against the angled side of the bolt. Gently, gently…

“Aw, it’s not going to work,” Patricia dismissed.

“Wait…”

Terri worked the card in further. The bolt moved a little.

“Wait,” Terri repeated, biting her lower lip as she concentrated.

The bolt moved a little more. Then—

click!

The door opened.

“You did it!” Patricia celebrated.

Yeah, Terri thought, a little surprised herself that she’d actually been able to. “Come on,” she said. “Let’s go check it out.”

The front room of the boathouse remained as Terri had last seen it, a refurbished office. There was the big desk next to the window, and on top of the desk sat stacks of papers, a typewriter, and a computer. There were also several high file cabinets.

“What’s all this stuff?” Patricia inquired, reaching out to pick up some of the papers laying on the desk.

“Don’t touch it!” Terri exclaimed. “We can’t touch anything, Patricia! If everything isn’t exactly the way my Mom left it, she’ll know we were here!”

“Oh,” Patricia slowly realized, pulling her hand away from the papers. “Sorry… But I wonder what all these papers and things are.”

“Just notes, from my mother’s zoology work.” Then Terri walked to the back of the office. There were two more doors against the rear wall. A sign on one door read SUPPLY ROOM, while the sign on the second door read DO NOT ENTER.

“Are those the rooms you were telling me about?” Patricia asked. “The rooms that your father told you to never go in?”

“Yeah,” Terri answered, her curiosity burning. Immediately, she put her hand on the knob to the supply room. The knob turned—the door was unlocked—and she went in, Patricia following close behind.

“Wait a minute,” Terri observed.

“This doesn’t look like any supply room to me,” Patricia noticed at once.

The room was full of more computers on big racks, with lots of blinking lights. There must’ve been half a dozen computer screens the size of small television sets. But one of the screens was turned on, and it had words on it.

Terri squinted at the screen and read some of the brightly lit words:

LOT 2: TRANSMISSION FAILURE

LOT 2a: TRANSMISSION FAILURE

LOT 3: POSITIVE REAGENT

TRANSMISSION OF GENETIC

CARNIVORE MUTATION

“What’s all that mean?” Terri asked.

“I don’t know,” Terri said, disappointed. She didn’t know what any of the words meant.

“Come on,” Patricia urged. “This room is dull. Let’s go into the other one.”

“Good idea.”

The girls went back out; Terri was careful to remember to close the door behind her—she knew it was very important that the boathouse be left as it was, otherwise, her mother and Uncle Chuck would surely guess that she’d been in here.

Terri’s frown was sharp when she turned the knob on the door marked DO NOT ENTER.

“It’s locked,” she said.

“Use the library card,” Patricia suggested. “It worked before.”

Terri was thinking just that. But this lock looked different; it looked more sturdy. Again, she slipped her laminated library card into the door’s gap and went to work.

“How come it’s not opening?” Patricia asked impatiently after a minute.

“This lock is harder,” Terri replied in concentrated frustration. “But… I think the bolt is moving…”

“I’m going to look around outside,” Patricia said. “Call out to me when you get the door open.”

“Okay. But be careful.”

Terri continued to work on the lock as her friend left the boathouse to examine the deck and the pier. The bolt of the doorlock continued to move as Terri wedged the library card in further, but it was much more difficult than the outside door. Come on, come on, she thought. Open! Time was growing short, and if she wasn’t careful, she fully realized that she could ruin the card.

Come on, come on…

And just as the bolt was about to open—

“Terriiiiiiiiii!” Patricia screamed from outside.

—Terri flinched in startlement. The library card slipped out of the door.

And the bolt snapped back into place.

But Terri wasn’t worried about that. She ran out to the pier, her thoughts racing along with her heart:

What happened! Why is Patricia screaming?

««—»»

When Terri ran out to the pier, Patricia, shuddering with fear, ran right into her.

“What’s wrong?” Terri demanded.

Patricia looked frantic, her blond hair going every which way. “There’s some thing on the edge of the pier,” she wheezed, nearly out of breath. “It’s black and slimy, and it’s really huge! I think it’s some kind of giant lizard!”

“Yeah, right, Patricia, just like you thought that old branch was a poisonous snake.”

“I’m serious, Terri!” Patricia insisted. “Go and look! It’s right around the corner!”

Terri skeptically did so, rounding the corner of the boathouse. But the instant she turned, she came to a dead stop.

She couldn’t believe what she was seeing.

Patricia was at least partly right. At the very end of the wooden pier-walk sat a shiny, coal black thing with four pudgy feet and a long tail. But it wasn’t a lizard—

“It’s a salamander,” she said distractedly. “I can tell by the yellow dots on its back.”

“It looks like a lizard to me,” Patricia remarked, clinging to Terri’s shoulders, still obviously afraid.

“Lizards are reptiles,” Terri informed her friend. “They can’t go in the water. But salamanders are amphibians.”

“Amphibians?”

“It’s a kind of animal that can live on land or in the water. Like toads and frogs. And that thing has definitely been in the water. You can tell. See how wet its skin is?”

“Well, yeah,” Patricia agreed.

“Besides, I know it’s a salamander because I’ve seen them before, and I’ve read about them in my Golden Nature books.” But this was where Terri’s knowledge of wildlife ended. “There’s only one problem,” she said, now even a little scared herself.

“What’s that?”

“Salamanders never get to be more than eight or ten inches long.” And after she said that, all she could do was stare at the puffy, wet, black thing on the pier.

“Eight to ten inches long?” Patricia questioned, staring in disbelief. “But that thing is—”

“I know,” Terri said, her own eyes wide in what she was seeing.

Because this salamander was no eight or ten inches.

It easily over three feet long.

««—»»

“Don’t go near it!” Patricia warned.

“I’m not,” Terri assured her. “I just want a closer look.” She still couldn’t believe it. She knew for a fact that salamanders didn’t get this big; she’d seen lots of salamanders in the yard, and they all had the same shiny black color with the bright yellow spots on their backs.

But I’ve never seen one this big, she reminded herself. Nothing even close to this…

The giant salamander lay there lazily. Terri could see its cheeks puffing in and out as it breathed, and its two big eyes on top of its head looked like giant black marbles that never blinked. Its tail alone must’ve been over a foot long itself.

I can’t believe this, Terri thought.

“Terri,” Patricia continued to nervously warn. “You better not get too close. That thing could bite you.”

“No, it can’t,” Terri responded, and leaned over to take another step. “Salamanders don’t have teeth.”

But then her own thoughts stalled right after she’d said that, and she couldn’t help but remember last night. Just when she’d finally convinced herself that what she’d seen was really just a dream—now, again, she wasn’t so sure. Toads don’t have teeth either, she reminded herself. But that toad I saw last night definitely had teeth…

And, then, when Terri took one more step toward the giant salamander—

The salamander lurched forward, its big lazy head raised, and it opened its thin-lipped mouth and hissed at her.

Terri’s heart thudded in her chest, and she jumped back.

Then she and Patricia screamed at the same time, because the salamander’s mouth stretched open wider, and Terri could easily see that it too had teeth.

Two rows of gleaming, white teeth that looked sharp as sewing needles.

Then the creature hissed again, and began to move toward Terri and Patricia, its jaw nearly snapping like a mad dog’s.

««—»»

“Run!” Terri yelled.

And they ran, all right, as fast as they’d ever run before in their lives, down the wooden pier-walk and back up the gravel path through the woods. The last thing they’d seen as they’d sprinted away in their sneakers was the salamander crawling after them on its fat feet, its tooth-filled mouth snapping open and shut as though it meant to bite them.

When Terri and Patricia got halfway back up the trail, they stopped to catch their breath. The uphill run left them winded and sweating, and they were still scared.

“It’s impossible,” Terri whispered. “I can’t believe what we just saw. A salamander with teeth.”

“Well you better believe it,” Patricia said, huffing and puffing. “And don’t try to tell me it was our eyes playing tricks on us. That was real.”

Terri nodded. This was definitely different from last night. Last night, she’d been sleeping restlessly, and she’d been groggy, and she supposed it was possible that her eyes had been playing tricks on her. But today? Just now? Terri knew this wasn’t a dream. It couldn’t be.

Something’s really wrong around here, she thought.

But what could she do?

If she told her mother and Uncle Chuck about the giant salamander, she’d get in lots of trouble for disobeying them. All kinds of trouble.

And then another thought rang in her mind like an alarm.

“Oh, no!” she fretted.

“What?” Patricia asked.

“How much time has gone by since Uncle Chuck took my mother to work?”

Patricia looked at her wristwatch. “About twenty-five minutes,” she said.

Terri’s thoughts exploded in her mind like a string of firecrackers.

Twenty-five minutes!

Patricia grabbed Terri’s arm. “What’s wrong?”

Terri gulped in dread. She looked over at Patricia and said, “I forgot to close the boathouse door. And I left my library card inside.”

“Terri!” Patricia exclaimed. “And your uncle’s going to be home any minute!”

“Yeah, and he’ll probably go straight to the boathouse to work, like he does almost every day.”

Terri had to think fast, and she knew she had to move fast too. “You go home right now,” she instructed Patricia. “If you’re at the house and I’m not with you, Uncle Chuck will know we’ve been up to something. Sneak around the side of the yard and go back to your house. I’ll call you later.”

Patricia looked confused. “But, Terri…what are you going to do?”

“I have to run back down to the boathouse, get my library card, and close the door.”

“Are you crazy!” Patricia nearly shrieked. “You can’t go back down there. That—that thing’s down there, that salamander or whatever it is. It’ll bite you for sure!”

“I’ll just have to be careful,” Terri concluded. “It probably went back into the water by now because most amphibians have to keep their skin wet, and, besides, salamanders are real slow.”

Patricia looked terrified at the idea of Terri going down to the boathouse by herself. “You better be careful, Terri, and I mean real careful.”

“I know, I will. I’ll call you later.”

Terri took a deep breath, then, and closed her eyes for a few moments. The image of the salamander, its fat, slimy body, and its needlelike teeth, still stuck in her mind. She’d never forget the way its jaw was snapping at them just before they ran away.

But I’ve got no choice, she told herself. I have to go back there, and I have to do it now.

And with that thought she opened her eyes again and turned. Then she began to jog back down the path.

Back—

A chill shot up her spine.

—back to the boathouse.

««—»»

Terri ran as fast as she could through the woods and down the winding path. Her sneakers scuffed the gravel; tiny tree branches reached out and threatened to brush her face. The path seemed strangely longer now, with more twists and turns. Just when she thought it would go on forever, she arrived at its end, spying the mirrorlike, silverish glare of sunlight off the lake.

The boathouse sat before her.

She stared at it, reluctant…

Afraid.

Hurry up! she screamed at herself then. You don’t have much time!

The wood planks creaked when she stepped onto the pier. She crept slowly along the walkway, keeping her eyes peeled for the hideous giant salamander. A salamander with teeth! she couldn’t help but keep reminding herself. But when she peeked around the corner of the boathouse, she saw that her earlier conclusions were quite right.

The salamander was gone.

It must’ve gone back into the water, she thought. And that was fine with her.

Quickly then, she trotted into the front room of the boathouse, to retrieve her library card. Her intentions were simple. Get the card, close the door behind her, and run back up to the house as fast as she could, before Uncle Chuck could wonder where she was, or worse, before he could come down here.

There it is!

She found the library card right where she knew it would be: on the floor in front of the door marked DO NOT ENTER. She picked it up, began to put it in the back pocket of her shorts. But—

Her curiosity seemed to wrestle with her, it seemed to tick in her head like a loud clock. She’d almost gotten the door open before, hadn’t she? I would have, she realized, if Patricia hadn’t screamed.

So…

She did what was probably the least sensible thing she could imagine. Instead of leaving, as she’d planned—

You really shouldn’t be doing this, Terri, she warned herself.

—she slipped the library card back out of her pocket. She couldn’t help it.

She simply had to know what was in that room!

Don’t mess around! she ordered herself. Sometimes Uncle Chuck stopped at the store after taking her mother to work; with any luck, he’d do the same thing today. Terri rushed to the DO NOT ENTER door, and slid the card back into the gap.

She worked quickly but carefully. Within moments she had the card wedged back between the bolt and the doorframe, and the bolt was moving again!

Come on! Open!

Then—

click!

She got it, and in good time! The door popped open…

Well, she thought. Here goes.

The room was very dark. Terri quickly felt along the wall next to the door, found the light switch, turned it on.

Then she stood and stared.

This room was nothing like the other room. There were no computers, no file cabinets. Along the front wall were big metal shelves, and each shelf contained rows of tall glass bottles which each seemed to be filled with some gross-looking yellow liquid. Gunky, she thought, making a face at a faint creeky smell. And then she noticed that a few of the bottles were full of green, not yellow, gunk. She had no idea what the stuff could be inside these bottles. Then she turned around—

The other three walls were lined with shelves too, but there weren’t any bottles on them. Instead, these shelves were filled with…

Fish tanks? she wondered.

No, not fish tanks, but terrariums: fish tanks with no water in them, and no fish. Instead each glass tank contained dirt and rocks and plants, with a small foil tray of water.

And they had animals in them too.

But not the kind of animals she would expect.

Toads, salamanders, newts—yes. But—

They were all huge—much bigger than normal.

And—

Terri gulped.

They all had teeth.

Just like the toad she thought she’d seen last night, and just like the three-foot-long salamander she and Patricia had seen only a few minutes ago.

Teeth.

Sharp, white, pointed teeth. Like a dog’s teeth, or a wolf’s.

It was so strange, and so scary…

This can’t possibly be, Terri thought, staring through the glass tanks.

Terri moved over to one particular tank, and looked intently in. There was a toad inside, sitting in the foil pan of water, but it was so big! It sat there in the tray of water, spread out and nearly the size of a kitten. Its gold-irised eyes were almost as large as the salamander’s, and a big white sac fluttered under its chin. But stranger still were the teeth. This toad’s teeth were so large that even with its mouth closed, the teeth stuck out past its lips like sharp, white fangs…

Taped to the front glass of the tank was a white sticker, which read in neatly typed letters:

COUNTER-REAGENT 6b ADMINISTERED

…and then there was a date.

The date was yesterday.

Terri remembered the words on the computer in the other room, especially the word reagent. But she didn’t know what that meant, nor did she know what counter-reagent meant.

She turned away, and then noticed something else.

Right there, in the middle of the floor…

What is that? she wondered.

A square outline cut into the wood-plank floor.

A trapdoor, she realized.

Yes, that’s what it was: a trapdoor. She would love to know what was under it, but there was a big lock on it, and it wasn’t any kind of lock she’d ever be able to open with her library card. It was a large, heavy-duty padlock, the kind of lock you needed a key to open.

What is under there? she had no choice but to wonder.

But she was definitely determined to find out, and she wanted to find a lot of things out. How could her mother and Uncle Chuck explain this? Giant toads and salamanders, with teeth? Weird bottles of yucky-looking yellow gunk? Locked trapdoors on the floor?

What was going on here?

But she didn’t let her burning curiosity stall her any longer. She remembered the time…

She had to get out of here, and fast!

She quickly pulled the door closed, heard the bolt click shut. She turned, moved quickly toward the outer boathouse door, and—

Froze in her tracks.

A figure was standing in the doorway, its arms crossed, and its foot impatiently tapping the floor.

Uncle Chuck.

««—»»

Uncle Chuck didn’t say anything, not one word for the whole time they were walking back up the trail to the house. Terri felt an inch tall; if there was one thing she knew about grownups, it was this: you could always tell how mad they were by how silent they were. The less they said, the more mad they were.

And Uncle Chuck wasn’t saying anything.

Terri knew she was in big, big trouble now.

They went in the house through the back sliding door. Then Uncle Chuck slammed the door shut.

“Sit down, young lady,” he said in the coldest voice she’d ever heard.

Terri sat at the kitchen table, her hands in her lap.

“I thought we had an understanding, Terri,” Uncle Chuck said, still standing up with his arms crossed, still tapping his foot.

“I’m sorry,” was all Terri could think to say.

“You’re sorry?” he said in a sarcastic tone. “What good is being sorry going to do if you fall into the lake and drown?”

“I can swim,” Terri feebly answered. “I won the 7th Grade swim meet last year, remember? I got a First Place ribbon.”

“Don’t get smart, young lady—”

Oh, yes, Terri knew she was in big trouble, all right. Because that was one other thing she knew all too well about grownups. When they called you “young lady” instead of your name—that meant BIG trouble.

“—that’s beside the point, and you know it,” Uncle Chuck continued in his cold, cold voice. “I don’t care how well you can swim. I can’t believe you disobeyed us. That’s just not like you. Now—” Uncle Chuck’s foot kept tapping away on the floor—tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap—“I want to know how long you were down there.”

“Just a little while,” Terri said.

“Just a little while,” Uncle Chuck repeated.

tap-tap-tap, went his foot.

“And haven’t we told you many times to never go down to the lake unless you were with an adult? Haven’t we told you many times to never go into the boathouse? Hmmm?”

“Yes,” Terri peeped.

“Then, why, young lady? Why did you do it?”

Terri couldn’t look up at her Uncle Chuck. “I…,” she began, but then she paused. What could she say? It occurred to her that she could lie to Uncle Chuck, she could maybe make up a story, she could say that she heard someone down there or something like that, and that she found the boathouse door already open. Maybe he would think there were burglars or something. But Terri didn’t like to lie, she knew it was something only crummy people did, and she also knew that when you lied, eventually the lie would catch up with you, and then you’d be in even more trouble.

So instead, she did what she felt was the right thing.

She told the truth.

“I was curious,” she told Uncle Chuck. “You and Mom spend so much time down there, I was curious. And—”

Again, she hesitated. If she told him about the toad she’d seen last night, or the giant salamander, he might not believe her. He’d think she was telling lies, and that would just get her in more trouble than she was already in.

“I was just curious,” she repeated.

Uncle Chuck looked down at her. His face looked made of stone, and his foot never stopped—

tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap

“I have a mind to call your mother at work right now and tell her what you’ve done, and the only reason I won’t is because it would upset her,” he said. “She’s very busy at work, and she works very, very hard, and since your father left, she has to work even harder to pay the bills and to keep food in the refrigerator and a roof over your head. It’s not easy for her, you know, and you just make it that much harder for her when you do things like this. That’s pretty selfish of you, isn’t it? That’s pretty darn inconsiderate of you.”

tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap

“And,” he continued, “do you have any idea how disappointed she’d be?”

Suddenly there were tears in Terri’s eyes. She felt smaller than a lima bean right now. She knew her mother worked hard to keep the house and everything, and the last thing in the world Terri would ever want to do was disappoint her mother. All at once, she never felt more ashamed of herself.

“I’m sorry,” she sobbed.

tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap

Uncle Chuck seemed to be cooling down a little now, though. “I want you to understand something, Terri. When your mother or I tell you to do something, or in this case, when we tell you not to do something, there’s always a good reason. And the reason is this: we told you not to go to the boathouse because it’s very dangerous for a girl your age down there. That pier is old. One of the planks could break, and you could break your ankle, or worse, you could fall in the water and drown. And there’s a lot of computers and electrical equipment in the boathouse; you could get an electrical shock and have to go to the hospital, or you could even die. Plus, there’s a lot of chemicals and things in the boathouse that are dangerous.”

Chemicals.

That reminded Terri of something. Those bottles, she thought. Those stinky bottles full of green and yellow gunk…

Was that what Uncle Chuck meant? Those tall, glass bottles she’d seen on the metal shelves?

“Anyway,” Uncle Chuck went on. “You’re going to your room now, and you’re going to spend the rest of the day there.”

Terri sniffled. “Am I grounded?”

“I don’t know, that’s up to your mother, not me. Go on now. Go to your room, and I don’t want to hear a single peep out of you, do you understand?”

Terri nodded. Then she got up from the table, her eyes still cast down to the floor, and she went to her room.

««—»»

Each minute seemed to tick by like an hour, and suddenly Terri’s room felt like a prison. I’ll go nuts cooped up in here all day long, she dreaded. Summer was almost over, and whenever she looked out her window, she could see what a beautiful day it was, and all that did was depress her even more. I could be outside playing badminton or doing something with Patricia, or—well, anything. Anything’s better than sitting in my room all day.

And, of course, once Uncle Chuck told her mother about catching her in the boathouse, she’d probably be grounded for the next week, or maybe even the next month…

And she didn’t even want to think about that.

But there were other things—scary things—that she had no choice but to think about: the toad she’d seen last night, the giant salamander, and all those other animals in the back room of the boathouse—all with long, sharp fangs.

Sitting on her bed, Terri pulled out some of her Golden Nature books. She had the whole series: Flowers, Trees, Rocks and Minerals, Mammals, Birds, and, the one she was most interested in now, Reptiles and Amphibians. These were great books that were informative and easy to read, plus they had lots of pictures; her father had given her the entire set of books as a Christmas present several years ago, because Terri had told him that she wanted to be a zoologist when she was older, just like him and Mom.

Amphibians, the book’s introduction began, are a special kind of animal that include frogs, toads, and salamanders. Amphibians are cold-blooded, which means that their body temperature varies with the weather, and they hibernate during the winter when it’s cold. Amphibians breathe air like most animals but they are unique because they can live in the water too, because that is where they lay their eggs, and they need to keep their skin wet. In fact, that is how amphibians drink water, they absorb it through their skin. Amphibians eat insects, moths, and worms…

Terri already knew this; she quickly turned through the pages to “Toads.” She wanted to double-check her facts. Maybe there were some rare kinds of toads that had fangs and ate animals instead of insects and worms.

The book also told about how toads laid eggs in ponds and fresh-water lakes—sometimes they laid as many as 20,000 eggs at a time—and that they slept during the day and only came out at night to feed. Terri already knew all about this too; this wasn’t the information she was looking for.

But then—

I knew it, she thought.

The book plainly stated that toads, however rare, had no teeth; instead, they had big, sticky tongues which shot out of their mouths to catch insects to eat. And the book also stated that American toads never grew larger than six inches long. The toad she’d seen last night was over a foot long! And so were the ones she’d seen in the glass tanks when she’d snuck into the backroom at the boathouse.

Then she turned to the “Salamanders” chapter and discovered the same thing. Salamanders never grew to be more than ten or so inches long, and Terri was sure the one she and Patricia had seen on the pier was easily three-feet in length, and the ones she’d seen in the glass tanks were huge too. And salamanders didn’t have teeth or fangs either. Like toads and frogs and all other amphibians, salamanders ate insects. In fact there was a special word for that, Terri noted. According to the book, toads, frogs, and salamanders were called insectivores, which meant that they only ate insects and worms.

But the toad I saw last night, she felt certain, was trying to eat that baby rabbit. And rabbits definitely aren’t insects! They’re mammals!

All these things, all these facts and details, only mystified Terri more. And she knew now that there was no way her eyes could have been playing tricks on her. Patricia had seen the salamander too.

Terri didn’t know what to do.

She wished she could call Patricia, but how could she? Uncle Chuck had confined her to her room all day, and he was in the house.

clack!

Terri glanced up. The sound she’d just heard was familiar, and after a moment’s thought, she knew what it was.

It was the sound of the back sliding door closing.

She went quickly to her bedroom window, which faced the back yard, and she saw—

What’s he doing? she wondered.

Her Uncle Chuck was walking across the yard.

Maybe he’s going to mow the grass, Terri considered, but that couldn’t be, could it? He’d have to go out front to the garage first, because that’s where they kept the lawnmower.

But then Terri saw what he was doing.

He had a briefcase in his hand, like one of the briefcases she saw him and her mother bring home every day…

So that’s where he’s going, she noticed next.

Uncle Chuck was walking toward the path, then entering the path, then disappearing into it between the trees.

The path that led down to the lake, and to the boathouse.

And that gave Terri an idea…

««—»»

You’re in enough trouble as it is, Terri reminded herself. You must be crazy to take a chance like this.

But she couldn’t help it; this was an opportunity she wouldn’t have otherwise.

Still peering out her bedroom window, she waited a few minutes, to give Uncle Chuck plenty of time to get down to the lake.

Then she left her room.

She had to be quick. Getting caught out of her room would get her in more trouble than she could even think about.

But she had to call Patricia.

She moved quickly yet quietly, back into the kitchen, keeping an eye on the big glass pane of the back sliding door so she could see if Uncle Chuck was coming back up to the house.

No sign of him.

She snatched up the phone and dialed Patricia’s number as quickly as she could—

beep-beep-beep

It was busy.

She hung up and decided to wait a few minutes, keeping her eyes glued to the path entrance in the back yard. She had no idea how long he’d be down there. Sometimes he worked in the boathouse with her mother for hours on end, and sometimes he went down there by himself for hours too. But, then again—

Maybe he’s only going down there for a few minutes, Terri considered. To check some notes or something. Or…

Here was another thought.

Maybe he’s going to the boathouse to check up behind me, to see if I touched anything, or broke anything.

But if that were the case, then why would he be taking the briefcase with him? The fact that he was carrying the briefcase seemed like a pretty good sign that he’d be down there for a while, probably several hours, as usual.

Terri scratched her chin. Another thought occurred to her. Yes, Uncle Chuck definitely caught her in the boathouse, but only in the front room. She had gotten the door to the back room closed before he’d seen her. Which meant:

He doesn’t know that I was even in the back room, she guessed. So that means he doesn’t know that I saw those glass tanks with all the big toads and salamanders in them, or those bottles of gunk, or that trapdoor on the floor with the padlock on it.

And there was one more thing. Uncle Chuck had never asked her how she was able to get into the boathouse in the first place, had he? No, Terri was sure he hadn’t, and that seemed pretty absent-minded of him. Usually, adults always asked about every little detail.

These questions itched at her, along with many others. But her biggest question for the moment was this:

What’s Mom going to say when she finds out I was in the boathouse?

But Terri pushed these questions aside, at least for the time being. She would have to worry about them later. Right now, though, her goal was to call Patricia.

Terri glanced out at the path entrance again, and didn’t see any sign of Uncle Chuck. Then she picked up the phone and redialed Patricia’s number.

It’s ringing! Terri thought.

A woman answered, Patricia’s mother. “Hello?”

“Hi,” Terri said. “May I please speak to Patricia?”

But suddenly Patricia’s mother sounded very upset, like something awful had happened. “Patricia’s not here right now,” she said, her voice shaking. “She—oh, the poor thing!”

“What?” Terri asked. “What happened?”

“Patricia had to go to the hospital—”

««—»»

The hospital!