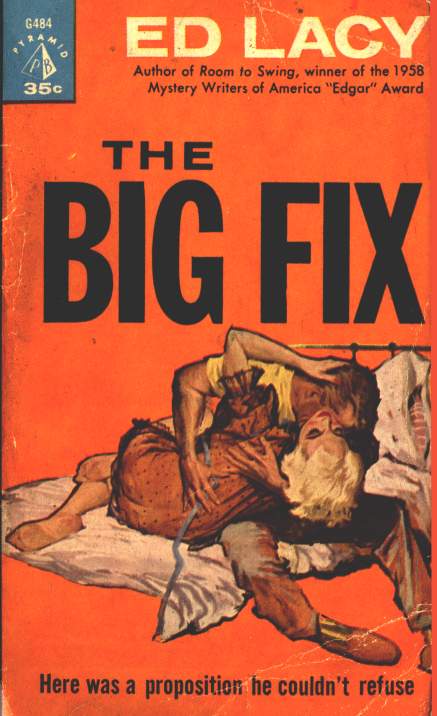

The Big Fix

Ed Lacy

This page formatted 2009 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

ARNO

TOMMY

ARNO

MAY

TOMMY

DETECTIVE STEINER

ARNO

RUTH STEINER

TOMMY

MAY CORK

TOMMY

ARNO

TOMMY

WALT STEINER

ALVIN HAMMER

JAKE

TOMMY

WALT STEINER

ARNO

TOMMY

JAKE

TOMMY

THE BIG FIX

by Ed Lacy

This book is fiction. No resemblance is intended between any character herein and any person, living or dead; any such resemblance is

purely coincidental.

For Willie P—the noted sand-shark catcher

ARNO

On the night Irish Tommy Cork's murder was planned, nothing very much out of the ordinary happened. Tommy was in the ring, taking a pasting—as usual. Back to the ropes, almost sitting on the second strand, Tommy crouched, gloved hands up in front of his face like a leather fence. He was fighting a strong youngster who was now whaling away with both hands in a moment of wild enthusiasm. Most of his blows were blocked, or ducked by Tommy's weaving head, but those few that didn't miss landed with loud thud sounds on the kidneys, head, or in the stomach, visibly shaking up the pale “old man.”

There were only two hundred and thirty-one fans in the fight arena, not counting the TV crew, and although the ring seemed to be a crowded oasis amid the sections of empty seats, Arno and Jake sat back in the shadows of the overhanging balcony—quite alone. Arno was popping tiny hunks of spicy fried coconut into his big mouth. Jake sat there looking almost bored, his sullen face blank.

“Well, what do you think of our pigeon?” Arno asked. “I been casing him for the last three weeks. A washed-up rumdum, hungry most of the time. But a real name—years ago. Fits in fine for us. Lost five of the seven bouts he's had this year. He's our new bankroll.”

Jake said, “If the ref don't stop it, the kid is liable to beat us to it—make Cork a stiff before we can get to him. Look at that dumb kid, wide open and swinging like a rusty gate. Wonder why Cork don't belt him? You sure he was good—once?”

“Yeah.”

“The way that kid swings is a crime. If I was in there with him, one punch would end the fight.

“Yeah, it sure would, kid,” Arno said, chewing on the coconut bits which he had purchased in a very fancy grocery, “either way. Jake, tomorrow you start.”

“Nuts, I'm in shape now, for a wreck like him. I could...”

“Shut up,” Arno said calmly but with a hint of whip-like menace under his voice. “We got too good a thing to be queered because you're a lazy bastard. You got to look the part, be on your toes. Tomorrow you start heavy training, Arno added as Tommy took a hard right on his quivering stomach, fell into a frantic clinch; his body deathly pale as he grabbed the muscular kid punching him.

The referee sort of snarled, “Come on, break clean, boys. Come on, Cork, you're holding. Break when I tell you!”

Jake shook his head, mumbled, “What a ref, ought to give him a soapbox for his speeches.”

TOMMY

The fight club was a dingy affair. One sports writer swore it still held a horsey smell although it hadn't been a stable for at least forty years. The stale air was full of smoke and numerous body odors. Somehow the clammy silence also seemed to hold the lingering roar of the few fans, the hoarse, phony yells.

If the club itself had a seamy odor, the cellar dressing room had the additional sharp stinks of damp decay, sweat, and liniments. As if a standard movie scene, the room was dimly lit by a single bulb and deserted except for the fighter on the ancient rubbing table. Tommy lay very still, eyes open, and at first glance seemed dead. The heavy, and wet-with-sweat, towel around his head like a shroud, disappeared into the faded and worn green robe with the large shamrock on the back. His unbandaged hands were neatly folded across his chest and scrawny hairy legs stuck out from the other end of the robe. A thin gold wedding ring was tied to the lace of his left boxing shoe.

Tommy's face was naturally pale and small (when he was a child his mother used to talk of his “button face") but numerous punches had left it with a constant puffiness, the nose slightly thick, some scar tissue ridged over his eyes— which were warm and friendly, and a trifle glassy at the moment. It wasn't an unattractive face. It held a kind of rugged good looks, combined with the cruel cast of a real fighter. His upper lip was thick with a small cut, there was a red-purple mouse under his left eye, and a bloody bruise high up on the other freckled cheek.

Tommy was humming to himself. Although deadly tired he was still full of the good relaxed feeling that comes when a fight is finished—win or lose. The door opened and Tommy raised his head for a second to watch Bobby Becker come in.

Becker was a short plump man in his late fifties, immaculately dressed in a conservative dark blue double-breasted suit, white on white shirt, and a neat dull red bow tie. His round face was pink, the large head shiny bald except for a faint fringe of dirty-white hair. Gold-framed glasses were delicately balanced on his big nose; a heavy black ribbon ran from the glasses to his lapel. His sight was perfect but when Bobby drove a rum truck back during Prohibition days somebody told him glasses made him look like a “professional” man. There was an empty amber cigar holder between his fat lips, which he sucked on now and then. The doctor said his heart wouldn't stand for cigars any more.

Tommy waved and tried to sit up, but the buzzing returned to his head, so he stretched out again. Here it comes, he thought. That dumb kid had to hit like a mule with his right. Jeez, I never seem to pick a soft one any more.

Becker asked, “What you doing, living here now?” His voice was gentle but shaded with the shrillness which comes to some men in their late years.

“I might at that. What's the rent?” Tommy said, suddenly thinking, Maybe Bobby can work out something. Let me sleep here in exchange for cleaning up, being a watchman? But it would have to be a secret, or it would spoil my rep.

Becker wrinkled his fat nose. “Sure stinks here.”

“But not of insecticide like the dump I'm living in.”

“Take your shower. I'm going to lock up soon as the TV boys get their equipment out.”

“I'm cooling off.”

“From what? You were cooling off the last two rounds. That kid has a good right.”

Tommy dismissed it with a wave of his left hand. “What right? Any goof can hit if he winds up and lets go like he was in a baseball game. Guy ought to be arrested if he lets himself get hit by that clumsy right.”

“Then you'd get life.”

Tommy forced himself to sit up, talked slowly to keep the buzzing in his head down. “Sony about tonight, Bobby. Kids these days are all headhunters. I didn't figure he'd have sense enough to go for my body. I had a plan. You saw the way this fool kid kept his hands up high, the way I worked his belly the first two rounds? Trouble was, in the third, when I finally got his guard down, I ran out of steam. Anyway, I wasn't stopped. I'll do better the next time.”

Becker moved toward the stained rubbing table as if to sit, then brushed nothing off his sharply creased pants and stood. “Tommy, I don't know if there'll be a next time. I don't know if I can squeeze you in any more for these emergency four-rounders.”

“Aw Bobby, you know I had an off-night. I can go a lousy four rounds any time.”

“Yeah? You barely did tonight. Full of wine?”

“Honest, Bobby, I'm sober. Just an off night. Bobby, you're the only break and hope I got left in the racket and...”

“Tommy, it may not be up to me. And you can get hurt bad.”

“Hurt? My experience is a big edge, Bobby. They don't get to me. The kid was lucky to rifle one through to my gut. Otherwise I'd have left-hooked him to death. I always give 'em a good show. Sure, he was a rough kid but... I'll level with you, Bobby. I sold a pint of blood yesterday afternoon.”

Becker looked horrified, had to keep his glasses from slipping off his nose. “Yesterday? My God, you're crazy!”

Tommy shrugged, then rubbed his big hands together, examining the lumpy knuckles. “Look, I was hungry, bad hungry. Would it have made any diff if I'd fainted from hunger out there tonight? I figured a day's rest would do it. It didn't.”

“You were also gambling the main go would last the distance and you could collect twenty buck for not going on!”

Tommy gave him as much of a grin as his cut lips could make. “Sure, I took a chance on that. You never lose a bet, Bobby? I watched the main event from the exit. That Billy Ash has a nice left. The way he took Georgie Davis out, mixing his punches, reminded me of myself in the Preston fight. I... Don't look at me like that, Bobby, I'm not going off into past history. Damn, everybody looks at me like I'm a punchy. You know I'll get up there again, Bobby. My hands are still good, never had no trouble with them....” He knocked on the wooden table, “Once I get eating regular again, get my strength back, I'll show these green kids what boxing is really like. What a good...”

“Tommy, lad, listen to me. I've been your friend for going on fifteen years. I'm the one who first spotted you in the amateurs. Believe me, you've had it. Quit now, before your brains are scrambled.”

“Nuts, I'm only thirty-two, I'll still make the big paydays again. I'll get up there, you know me, the luck of the Irish.”

Becker sighed. “You and your big talk; you never even been to Ireland. Remember me, I was born in Kilkenny. It's a poor, hungry, cold country. If there's any luck, it's mostly bad.”

“You sound like a lousy Black and Tan.”

Becker held up the back of his fat hand. “Watch your mouth before I finish the shellacking you was taking in the ring.”

“Bobby, you said we been pals. You know me, how I can fight. So I had a bad night but...”

“It was on TV, too. Seeing a guy get a beating isn't good for the family. The sponsor gets complaints and... Getting to be a hell of a deal where I have to worry about ad executives and what some cigarette man's wife thinks.”

“But if I hadn't sold my blood, I'd have flattened this rough kid. Match me with him again and you'll see. Why, if I was in shape, I would have looked real good against a musclehead like him. Then you could have set me up for a regular four-rounder next week. I win that, maybe one of the mob managers gets interested in me, and I'm making folding dough again.”

Bobby Becker brushed his suit again as he said, “If, if, if. Wise up, Tommy, you're hanging around for nothing. Even if you still had it, it would be for nothing. I don't have to tell you TV has killed the racket, strangled the small clubs. You tell me, why should a joker go out and pay to see a bout when he can sit on his butt on his own couch and watch 'em for free? Why not long ago, before the second war, why there was a couple hundred small clubs across the country, at least a dozen I remember within fifty miles of here. Even a willing bum could fight two or three times a month. Now, there ain't twenty clubs in the whole U.S.A., a lousy three in this state, and I'm the only area operating weekly here. I lose my TV contract, I'm done. You seen the big crowd tonight, three hundred people! Okay, the TV fee carries me, but a pug has no place to learn his trade any more. In the old days a kid had maybe thirty or forty fights before he hit a main event. Now he's lucky to have thirteen fights in his whole career. Marciano had under fifty when he retired. Things are too tight. The 'in' managers keep maybe a dozen guys working steady, the rest don't make bread. Face it, Tommy, you've been washed up for years. Go get a job.”

“They're waiting for me on Wall Street! This is all I know. I always been a pug, never wanted to be anything else. You know that. I never even had a Social Security card, until last month. You're wrong, Bobby. If TV has ruined the small clubs, it's also brought in the big money. Like you said, the pugs today are all novices. Once I get my break, I'll go over big. How many hundred-bout fighters like myself are around? TV has... Oh my God, I sure hope May didn't watch me on TV tonight.”

Becker pulled out a folded handkerchief, carefully wiped his cigar holder. Not looking at Tommy he said, “The commission doc said something about revoking your license, kid.”

“What?” The boxer actually leaped off the table.

Becker nodded, replaced the empty holder between his lips. Then he said, “You looked terrible in there, covered up against the ropes most of the time, your legs shaking like you were being killed, the fans screaming to stop it. That's what I meant by it not being up to me. Well, take your shower. Here's your dough.” Bobby took a bulky roll of bills from his pants pocket. “Sixty dollars—minus my twenty, minus the fifteen you're into me from last month. I had to pay your second's six bucks. That's thirty-five... forty-one dollars. Here's yours—nineteen. Does your lip need stitching?”

“Naw, ain't nothing. You know me, never was a bleeder.” Tommy took a large cracked suitcase from one of the busted wooden wall lockers. Opening the suitcase on the table, he removed wooden shower clogs and a crumpled Turkish towel. The suitcase was jammed with clean and dirty underwear, sweaters, socks, a pair of old shoes, and a shirt. Becker asked, “Haven't you a room no more?”

“Of course. You think I'm a bum?”

“Why you carting all your stuff around with you?”

“I'm not living at the Waldorf. Stuff gets stolen.”

“You mean you can't chance being locked out.” He sighed again. “I don't know, kid, you once looked like money in the bank—a dozen years ago. If you hadn't insisted on the Robinson fight...”

“Becker, cut it. I'll be up there yet,” Tommy said, taking off his robe, trunks, and protector. His red hair was getting thin, there was a growing bald spot on the top of his head. He had hairy arms and legs but his chest was smooth, and there was a dried-up look to the flat white stomach, the narrow hips, skinny backside. Even the too sharply defined shoulder and back muscles seemed drawn. Cork's thin one hundred and forty-six pounds reminded Becker of one of these medical drawings in a TV ad showing the various veins, muscles, and joints. As the fighter bent down to remove his shoes, Becker noticed the wedding ring tied to the laces. Annoyed, he said, “And how did that look, taking your ring into the fight? Told you before, never have to worry about anything being stolen in my club.”

“You should have seen the characters in here tonight. If there was a way of doing it, I'd have taken my suitcase into the ring.”

“That old wedding ring. If it was worth anything, you would have hocked it long ago. A cheap...”

Tommy straightened up, a fast movement that increased the pounding in his head. He held on to the table for a second. But his eyes narrowed and his face turned cruel and hard. Then he relaxed, said gently, “Bobby, you know better than to call it cheap. You really know.” He sat down to take off his ring shoes and socks, dropped the wedding ring on the table, atop the pile of money. Slipping on the wooden shower shoes and taking the towel, he clopped toward the coffin-like shower, calling out, “Watch that for me.”

“I have to go back up....”

“Only be a few minutes,” Tommy said, turning on the water.

Biting on his cigar holder, Becker stared at the wedding ring, silently cursed it. He heard steps in the hallway and turned to see Alvin Hammer stoop to walk through the dressing room door. Hammer was five inches over six feet tall and weighed less than one hundred and forty pounds. His clothes were casual and expensive, and heavy framed glasses gave his lean face an owlish look often considered intellectual. His nervous face still held a trace of an actor's good looks despite his baggy eyes and receding hair, which was dyed black. (On TV he always wore a hairpiece, of course.) He was now smoking a handsome pipe and an amazingly deep, clear voice managed to come out of his skinny frame as he said, “My boys are all cleared away, Becker. How's the kid?”

“Taking a shower. Watch his stuff, I have things to do upstairs.”

The announcer sat on the rubbing table. “He was completely tragic in there tonight. A magnificent display of... This all he gets?”

Al's eyes counted the money under the ring, then looked over abruptly at Becker, who snapped, “Stop it, Al. Go peddle your shaving soap and cut the do-good act. I'm running a business here.”

“He would have been a famous champ if you hadn't thrown him in with Robinson!”

“What do you know about it? Tommy wanted the fight.”

“I know he never recovered from that beating,” Al said, his voice clean and ringing.

Becker cleaned his cigar holder again and wrinkled his face as if about to spit. Then he remembered that in a fashion Alvin was his boss. He had so many bosses these days. Heading for the door he said, “I can remember when you screamed at him to go out, with his eye half open from a butt, to fill up a few minutes of open TV time! Leave me alone, Al, I have my own problems. Believe me.”

Alone in the dreary dressing room, Alvin stared at the pathetic pile of money, the wedding ring and enjoyed his pity. He glanced around the room, as if drinking in the horrible atmosphere. After many years as an unsuccessful actor and part-time spieler on sight-seeing buses, then a minor success on radio, Al had rung the bell as a TV fight announcer.

“Money-wise” he wasn't big, but he made a fair salary and far more important, thoroughly enjoyed his work. Having been a sickly kid who grew too fast into a painfully thin man, Al was fascinated by muscles, by athletes, by men able to give and take punishment. He liked being “a part” of the fight game. “I indeed consider myself fortunate to play any role in this intense drama of courage and skill, in this age-old contest of man against man,” Alvin would say— and often. His open excitement and sincere admiration for pugs wasn't cynical, as is the case of most sports writers, and a great deal of Alvin's sincere feeling came through the mike, making him most effective with his listeners. Although some of his descriptions of movements and precise blows were entirely wrong, the average TV fan never knew the difference and at times Al's vivid description sounded as if he were up there in the squared circle—as he undoubtedly was, in his mind.

One time on the air, talking about a hard gut wallop, Alvin had said, “Oh! Oh! Frank rips a terrible right deep into Brown's stomach. Brown is clinching, his eyes rolling. Our mouth is desperately open, fighting for air. Now our stomach muscles grow numb, our legs go deadly tired. I feel as if I'm sinking into a numbing fog. Hold on! My heart cries out. Hold on for dear life!... Ah, now our nerves and reflexes respond, we shake off the lifeless feeling, energy and strength are flowing back into our trained muscles. The fog lifts from our brain and... There! Brown is fighting back like a wounded tiger....”

The sports writers razzed Al without mercy, but the fans like it, showered the stations with letters.

If Alvin's blind worship of “courage” made him fail to understand the stupidity and commercialized brutality of the fight racket, he could feel and understand the tragedy, the violence. Now, remembering the beating the nineteen dollars represented, he was moved to tears.

Alvin, after two failures at marriage, only saw women out of need and was “married” to his job. This marriage worked for him. People on the fringe of sports often adopt an athlete (often not aware they are doing it), one they may feel close to for any one of a hundred different reasons. Al was very fond of Tommy. “The little fighting cock,” as he loved to call him (although not on the air where it might possibly be misconstrued) had once saved a show for Alvin. From that moment on he was Alvin's favorite pug.

Tommy came out of the shower stall dripping wet, rubbing himself vigorously with the towel—the hotel name too faded to be legible. The cold shower had washed most of the dizziness and pain from his body. He waved and said, “Hello, Al. Sorry I stunk up your show. I couldn't get started.”

“He was a strong youngster.”

“Muscle-bound dummy. In the old days I wouldn't have let him carry my bag.”

“You would have cut him to ribbons with your left in a round,” Alvin said, although he'd never seen Tommy box before a year ago, when Cork had been way past his prime. Indignation shook his voice as he asked, “I thought you were paid sixty dollars for an emergency bout?”

“That's the price,” Tommy said, powdering his crotch and between the toes. It often made him nervous the way Al stared at him. He sometimes wondered if the announcer was a queer.

“Then why these few dollars?”

“Well, fifteen bucks I owed Bobby. Six went for the seconds, and Bobby gets his one-third cut, like a manager, for getting me the bout,” Tommy explained as he put on his torn underwear.

Al banged the rubbing table, a tremendous thump. “The cheap bastard! Where does he come off taking a manager's cut? He knows it's against the law for a matchmaker to be a manager, too. I'll have a word with him!”

Tommy looked up, surprised. “Look, Bobby gives me the breaks.”

“Ice in the wintertime!”

“Don't forget, he used to be my manager,” Tommy said, slipping on socks and badly cracked shoes. “It isn't easy for him to get me on the card. Plenty of mob managers are after Bobby to give their boys the cellar fight. Old Becker's been a pal to me.”

“With a pal like him you don't need enemies, as the joke goes.” Alvin put a hand in his pocket. “Irish, you need a-few bucks?”

“Naw, I'm into you for near a hundred now. This dough will last me until I get another bout.”

“You may not fight for weeks. Got any money beside this nineteen dollars?”

“Yeah!” Tommy fingered the change in his pocket as he buttoned his baggy pants.

“Irish,” Alvin began, hunting for the right words, “maybe you ought to... take a rest? I mean for a few months....”

“Listen, AL you don't have to tell me I was pure lousy tonight. We all have our off-nights. Bobby says the commission wants to take away my license. I'm only thirty-two. Archie Moore and Jersey Joe, and old Fitz—they never hit the big time until they were forty. Things been rough for me, I haven't been training right and...” Tommy almost said he hadn't been eating most of the time, but somehow he couldn't tell Al that. Al was the “press” and one always put up a front for the press. “You know I got the fastest left in the business. I have the experience. Hell, I'm no sixty-buck fighter. I made seven grand fighting Robinson. I ain't got any doubts. You wait, with the luck of the Irish I'll be up on top again, where I belong.”

“Of course, you'll be a champ. I merely thought that if you had a rest, it might be what you need.”

Tommy thought, How dumb these reporters are! He slipped on his ring, pocketed the money, and quickly packed his old suitcase. He put on an old windbreaker under an older heavy coat. “Al, resting isn't what I need. This was my first fight in nine weeks. I need more bouts. Hell, it costs to rest.”

“Suppose I give... lend you twenty-five dollars?”

Tommy shook his head. “Al what you can do is get me a part-time job, something which won't interfere with my training but give me eating dough. I could work out evenings, like most pugs do now. Ought to be lots of things around a TV studio to do.”

“Well, I'll ask.” Alvin couldn't hide the doubt in his voice.

“Something where I'd get a workout at the same time. Like pushing chairs and stuff around, physical work.”

“Irish, all those jobs are highly unionized.”

“I'll even be a porter or a messenger—just a couple hours a day,” Tommy said, putting on his cap, turning off the light. “Watch your head in the doorway, Al. I'd only need the job for a few weeks. If I hadn't run out of steam I'd have flattened this rough kid, been on the way up. AL wasn't it comical, the way he telegraphed his right?”

“He's a clumsy oaf, should quit now, while he's ahead,” Alvin said, his arm around Tommy's shoulder. They walked up the wooden steps and into the dark arena, their Mutt and Jeff shadows dancing ahead of them. In the dim light the empty arena, filled with an unreal fog of stale smoke, always gave Al a nightmarish quality. They passed Becker in the box office with his bookkeeper. Alvin stopped at the main entrance. “I forgot my coat. Irish, if I should hear about a job—and I'll try but can't promise anything—how do I get in touch with you? Haven't seen you around the bar lately.”

“Leave word with Bobby.”

“Or I'll see you at the gym?”

“Well... eh... best you tell Bobby,” Tommy told him. He owed three months' rent at the gym—fifteen dollars all told—hadn't been around there in weeks. “Hey, Al, how did you like that talking ref? Must have been afraid to work, get his hands dirty. Talk, talk... I was busy enough with the kid without listening to a lecture.”

“He should work in England, where the referee is outside the ring and only gives voice commands,” Alvin said. “Okay, old cock, I'll keep in touch. And, if things get too rugged, don't hesitate to look me up for a few bucks.”

“Thanks,” Tommy said politely, thinking, Why the devil doesn't he stop treating me like a bum? I'm Irish Cork, the welterweight contender!

Outside, it was a raw, cold night. Tommy started walking, needing food and a good hooker of whiskey, and not sure of the exact order of need. The cold air stung his battered face, cleared his head. Almost copying a hackneyed scene from a B movie, a flashy sport car, parked on the deserted street, sounded its horn. Tommy knew it wasn't for him and continued to walk. He decided to get the drink first—only one— then head for a cheap cafeteria down around the skid-row area where he could put away a filling meal for about a buck.

Continuing the motion picture scene, the horn pierced the night again and a stocky young man in a well-fitting overcoat, wearing a sharp hat, crossed the sidewalk and stopped in front of Tommy. “You Irish Cork?”

“Sure.” In the dim light Tommy could make out the hard, handsome features, the thick shoulders.

“There's a guy who wants to see you in the car. May have a good deal for you, Pops.” The voice was flat, casual, yet from the way the younger man was blocking him, Tommy had a fast feeling it was more of an order than an invitation.

“He wants to see me?” Tommy put his bag down so his mitts would be free, never taking his eyes off the other's hands.

“That's it. Kind of a fan of yours.”

Tommy chuckled. “Think he wants my autograph?”

“Why not ask him?” Jake lowered his voice to a supposedly confidential whisper. “Pops, this guy's a fight nut And a rich one. Let's go, huh?”

For a split second Irish hesitated. It wasn't exactly fear. Tommy really believed he could lick any man in the world, including the heavyweight champ. Rather, it was a cautious curiosity. He vaguely wondered what this heavy-shouldered guy would do if he told him to go to hell; and what he could do himself, considering how weak and exhausted he was. Then he told himself, I'm thinking like a clown. What am I, a millionaire they're trying to kidnap? And I'm too poor to be sued. They must mistake me for somebody else. But he called me by name? One thing, I sure don't look like ready money.

Picking up his battered suitcase, Tommy followed the man to the car, deciding he'd see what this was all about but he'd be damned if he'd get in.

There was a plump man sitting on the front seat. He was bundled in an expensive coat. The features of the fleshy face were sloppy and the light from the dashboard showed a veined nose, wide mouth, and quick, clear eyes. Sticking out a gloved hand the man said, “I'm Arno Brewer. I'm thinking of managing you. You've already met Jake—Jake Watson, one of my fighters.”

“Manage me?” Tommy repeated, shaking hands carefully. “Why not? Want to talk this over on a drink?”

“I never touch the stuff. You didn't see me fight tonight.”

“But I did. That's when I decided I was interested in you. I know, you looked downright lousy in there. But you were obviously far out of shape. However I saw flashes of, your old form and... Sure you won't have a few shots?”

No sir, I always keep in training:

“No point in discussing things tonight. I'm at the Southside Hotel. Suppose you drop up tomorrow and we talk about it then? You haven't a manager, have you Irish?”

“No, not at the moment.”

“Fine. No worry about buying up the contract. Remember the....”

Tommy blinked. “You'd be willing to buy my contract, if I had one? No kidding?”

Arno said in the fast, nervous way he had of speaking, “You'll find me a man of direct action. Once I make up my mind. I see you in there and I say to myself, 'This guy has class. And he's the last of the Irish pugs.' I'm part Irish myself, way back on my father's side. You be at my hotel in the morning. Not before noon, like my sleep. I'll not only manage you but see you train right and eat regularly.”

“You will?”

“Mr. Brewer isn't in this for money, Pops,” Jake put in. “Like I told you, he's a fan, and this is a side line for him. A... eh...”

“Hobby,” Arno added. “Will I see you in the morning?”

“You bet.”

Jake walked around the car, got behind the wheel. As he drove off Arno called out, “Brewer is my name. Southside Hotel at noon. Don't forget, Tommy.”

Tommy nodded and shut his eyes. He opened them to see the car turn the corner, so it was all real. He spun around and started walking west. This unbelievable news called for a change in plans. He must tell May his good luck, after he stopped for a drink.

ARNO

Stopping for a light, Jake asked, “We going to see some broads tonight?”

“You can,” Arno said. “I'm too old for so much action. And this is your last time until we settle with Cork.”

“He isn't in the bag yet,” Jake said, a sort of grant. “We should have taken him with us. Might not show tomorrow.”

“He will. I don't understand it myself but some guys go for fighting as if it was dope.” Arno glanced at Jake. “Like you would be carrying a broken-down suitcase out of some fight club now—if I hadn't wised you up.”

MAY

The exchange diner was open twenty-four hours a day but at noon and 6:00 p.m. when restaurants are usually busy, they were lucky to sell more than a few cups of Java. However, from ten in the evening to late morning they did a good business. The diner, actually a dining car on a brick foundation, stood at the edge of the wholesale produce market area and was patronized by truck drivers and their helpers, merchants, and slaughter house and produce workers. Four waitresses worked around the clock, for tips and meals only. The tips were hardly anything to shout about and May Cork was the only waitress who'd stayed there over a year.

Dressed in a simple blue smock and white apron, she was usually called “Old May” by the steady customers, although she was only twenty-nine. May's gray and auburn hair was worn in a tight bun and her face was pale and delicate, as if she had never seen the sun. Her meek eyes were large, the mouth thin. The bosses liked May because she was a steady worker, never horsed around with the male customers—although at the end of her eight-hour shift she often looked as if she was about to pass out. Other waitresses came and went—often with a tracker headed back toward Florida, or for New York City. Since she was plain looking and flat-chested, May had established some sort of record in the diner: during all the months she had worked there nobody had made a pass at her.

Her boss (actually he was one of three partners) also liked May being religious, the medals she wore around her thin neck, the fact she went to church regularly. May had worked on his shift ever since she started there. He was a middle-aged man named Frederick Morris III, a direct descendant of a Pilgrim, now known only as “Butch” and rightly so since he had been a ship's butcher, bought and cut most of the meat used in the diner.

At ten forty-five that night, the afternoon waitress, a blonde named Bertha who always seemed about to serve up her fat bosom whenever she bent over to place a plate before a customer, dropped in for a free cup of coffee. She told May, “Well, honey, I'm set. Got a letter from my sister in Fresno. You know, the one who married the guy with the nut ranch out there? She's going to open that roadside stand I told you about, and they want me to help out. Who knows, maybe I'll meet a decent pair of pants in California. Anyway, they say the weather is nice and for the next three months my lucky stars are bright in the sky, so I'll see which way things bounce. Be something working in the sun. I've had it in this damn cold city.”

“When are you leaving?” May asked anxiously.

“Soon as they finish building the stand, in about a month. Her husband is one of these loudmouths who knows everything, but I guess I'll be able to take him. And they have a real house. And two kids. Ill like that. Funny, Betty— that's my sister—never had no looks. She was sort of the ugly duckling of us four babes, yet she made out the best. Never thought I'd be asking her for...”

“Bertha, can I get your apartment?” May cut in.

“Sure. That's what I come to tell you.”

May reached across the counter and squeezed the blonde's cigarette-stained hand. “Oh, Bertha, you honestly mean it?”

“Didn't I always say if I gave up the joint, it was yours? I even spoke to the agent today. No fifteen per cent raise. Only been seven months since I gave the bastard an increase, so he ain't entitled to one now. Don't let him fast talk you into paying a cent more than the forty-eight dollars a month.”

“Yes, yes, indeed! Oh Bertha, you're so sweet! You've no idea what this means to me. An apartment of my own again!”

“It ain't no hell, you seen it. Room, kitchenette, and the can. You remember how I got it fixed up?”

“Yes. Oh, Bertha, you can't know what this means to me.”

“May, stop bubbling and listen. The studio couch alone cost me two hundred bucks. And there's a couple chairs and the table, curtains, pots, and dishes. I'm taking the TV with me but it don't pay to ship the rest of the stuff. I figure a hundred and fifty bucks is a fair price to ask. Okay?”

“Fair, very fair,” May said, her face flushed with excitement “Bertha, I'll mention you in my prayers. I haven't got the money now, you understand, but in a month's time I'll get it.”

“With what these big-hearted slobs leave you? You're the thrifty type, ain'tcha got nothing put by?”

“Less than twenty dollars. But don't worry, I'll see my husband. This is what I've been waiting for. I'll see Thomas and within a month, we'll be able to pay you.”

Bertha finished her coffee, lit a cigarette as she stood up. Reaching inside her dress top to adjust her bra straps, Bertha okayed herself in the mirror behind the counter, said, “Don't keep me waiting too long, May. I'm doing you a favor and counting on that dough to take me to Fresno in style; you know?” Bertha glanced at the few customers, started toward the door, then stopped to ask, “Didn't you once tell me your old man was a leatherpusher? Tommy Cork?”

“Irish Tommy Cork.”

“I seen him on TV just now. What a beating he took.”

May's thin face paled. Looking up at the greasy ceiling of the diner for a fast second, she said, “Maybe this is all God's will. Even the beating will work in with my plans.” Then she added, almost fiercely, “Tommy was a good boxer, real famous—once. I have clippings in my room I can show you.”

“Honey, I believe you. He's your old man, not mine. Look, I got a couple runs to make. So it's a deal now, about the furniture?”

“Absolutely. God bless you, Bertha.”

After the blonde left May went about her work in a small daze, thinking how she could get in touch with Tommy. Tomorrow she'd go over to the gym, somebody there would know where to reach him. Or maybe that bar he mentioned, if she could recall the name. She called over to Butch, “Is that job still open at Mac's place?”

“What job?”

“I overheard him telling you last night he needs a dishwasher-porter. I... I may know somebody who will want it.”

“That job will always be open,” Butch said. “Who but a wino will work for twenty bucks a week and grub? Even a lush only holds it for a week or two. Mac's going to get himself in a jam with the labor commission.”

“Still, it might be a start, for the right man,” May said, turning to wait on a customer.

At midnight the diner was fairly busy as many of the market men came in for “lunch.” At a quarter to one May was astonished to see Tommy walk in. She was cleaning the counter and motioned for him to take a stool at the far end. Talking thickly, due to his big lip and a few ryes, Tommy said, “May, honey, I have great news! Seems like I'm getting that break, at last. Be like old times soon.”

“Oh, Tommy, Tommy, this is a miracle,” she said, stroking his puffed face. “I have such fine news, tool The truth is, I was thinking all night of how I could get in touch with you. Does your face hurt much?”

“Pay my puss no mind, I had an off-night. But all that is changing, so is my luck. I said to myself I'll eat here and tell you the big news. I got a...”

“Good news, indeed! Eat while I talk to you. Are you hungry?”

“I'm starved, honey.”

“I'll fix you a bowl of thick soup and the hamburger is good, and fresh. With plenty of french fries, the way you always loved them. Then I'll... No, I'll burst if I don't tell you the news now! Tommy, we can be together again. I've found us an apartment!”

Butch, who was busy chewing a toothpick behind the cash register, glanced at May and the little man with the bruised face and battered suitcase, the animated way they were talking. He started over to see if May was having any trouble with this red-headed bum, when she raced down the raised duckboards behind the counter, told him, “That's my husband there. Fred, will you make him a very special thick hamburger, no onions, but lots of french fries? I can't get over it, Tommy showing up just when I was thinking about him!” May's sudden coloring, her excited eyes, startled Butch: she almost looked youthful.

May beamed at Tommy as he ate his soup—taken from the bottom of the pot so it was thick with meat and vegetables—and went through several rolls. She was especially happy to see he was still wearing his wedding ring. Butch even waited on a customer to give May time to be with Tommy. Butch was puzzled. While he vaguely knew she sometimes spoke of a husband, it was hard to imagine her falling for this hard-faced bum, a lush who looked as if he'd just come from a street brawl, not a gentle, religious woman like May.

Waiting for his hamburger, Tommy began, “May, it was like a dream. A rich guy...”

“No, when you're finished we'll talk. Tommy, what news, what sweet news!”

He winked. “Like you when you're excited, May. Makes you look even prettier than usual.”

“Now stop that blarney,” she said, pleased. “Does your lip hurt?”

“Naw. I was in against some strong, lucky kid who... Maybe that's over now, all these quickie bouts.”

“Yes, thank God it's over, darling,” May said as Butch called out the hamburger was ready.

Tommy was barely able to put the thick meat patty away and when May said, “The pies are so-so but the bread pudding is made here and good...” He held up a hand, told her, “Hon, I'm stuffed like a Thanksgiving turkey now. It was a swell feed but I've had all I can eat.” Tommy pulled out a five dollar bill. “Here—and keep the change. I always tip beautiful waitresses big.”

“Nonsense. I... Tom, have you money?”

“This and a ten spot. But that's all going to change. May, I'm going to take you out of this stool joint, no more working for you. See, I got a new manager interested in me. A rich cat. Welters are all bums today, and with him staking me, and he has to have an in, why I'll be on top of...”

“Thomas Cork, you mean you're going to continue fighting?”

He blinked. “May, this is my break. Sure I'm going to fight, but for folding dough.”

“I thought... you said... it was over? I heard you took a bad licking tonight. Tom, you're no longer a kid. I thought you were done with fighting.”

“What am I telling you except about this new manager I'm to see tomorrow? He don't sound like a false alarm, and with him backing me, why...”

“Tom, listen to me. One of the girls here is going to California in a month. She has an apartment. It isn't much, one room really, but it's a real apartment. The rent isn't high and she's only asking a hundred and fifty dollars for the furniture. Of course it isn't worth that, but for these days it's a bargain. We have a month to raise the hundred and fifty.”

“Peanuts. One semi-final and I'll have enough to...”

“No! I don't want you to fight. And I don't want any more of your big empty talk either. Tom, you're done as a fighter, we both know it. Look at you, a kid beating you up. I don't want you ending up hurt or crazy, going blind.”

“May, that's no way to talk. I ain't bragging, but you know how good I am when I'm right.”

May nodded. “You were good in the ring, the best. But that's yesterday, today prelim kids are cutting you up. Maybe I mined all that for you, but...”

“Don't ever think that way, May. It wasn't you or...”

“I don't want to discuss it. That's all yesterday. Tom, I've been thinking a lot about us. When you're lonely you think. My sickness, the army, you away training so much, we never had our chance at happiness, really being man and wife. You know what's the key to everything? A home—an apartment! We got to have the same roof over our heads before we can start a thing. I'm sick to death of rooms, sharing a bath, keeping food on the window sill, using somebody else's furniture. We have to have a place of our own, an apartment that's ours, where we can live like normal humans. A room is only a cage, and the street our living room. But with a real apartment, where we can cook and live and... God has been gracious to us. We can have Bertha's apartment, if we can raise the hundred and fifty within a month. We must save about forty dollars a week. Now I usually make about thirty-five dollars in tips here. I'm paying eight for a room, so I can hustle together about twenty-five dollars a week. I know where you can get a dishwashing job. It don't pay much, only twenty dollars a week with meals. But it's a start.”

“May, baby, I was once a contender for the title. I'm a pug with the best left hand in the business, not a dishwasher.”

“For once you'll do what I say, and I won't hear any more talk about fighting! I can't stand it. All the worry and fear. Tom, Tom, don't you understand, this apartment is a gift from Heaven, our last chance! Once we get the hundred and fifty up, then with the both of us working, we can easily pay the rent, in time put a little aside. We'll be together, have some... security. But you have to forget the ring. I can't carry this alone. You have to get a job!”

“You're playing us short, May. I want nothing more than to be with you. But twenty lousy bucks for washing some stinking dishes. May, I once fought Robinson. You know what the TV cut is on a main event in Bobby's club? At least a grand, after my purse is pieced off. I haven't got many years left to grab that kind of dough.”

“Tom, you haven't got any time left, for boxing. All I ask is you get a job, like any other husband does.”

“Sure, people are dying to give me work. I'll tell you something, before I got this break tonight I was ready to quit. I was so broke I did look for a job. Once glance at my face and they said no dice. Or they asked what my “work background” was—and just to be a lousy messenger. The moment I said I'd been a pug, you'd think I'd said thug. I even got a Social Security card so I could deliver telephone books for a few days. Over the weekends I deliver for a liquor store, pull down a few bucks in tips. Okay, that's only marking time, temporary. I'm Irish Tommy Cork, and I don't settle for being a greaseball dish jockey the rest of my life!”

“I don't want you to be one for the rest of your life either, but until we're settled, at least get the apartment, we need money coming in every week, money we can count on. Tom, keep the liquor store job, too. In a year, you can look around, or maybe become a counterman, or short-order cook or...”

“May, I can't lay off a year from the ring. I'd be...”

“Can't you forget boxing? Can't you understand what a home of our own will mean? The way we've been... existing... one miserable room after the other, the both of us living as strangers in a lonely world. It was living in rooms that made us fight and separate. Tommy, we're no longer kids. We don't have too much time left to be... us. What I'm trying to say is, we have to think of our happiness not of the ring, or of anything else. We have to start living.”

“Don't you think I want that? What you think I'm fighting for?”

“I suppose you are trying, in your own way, but... Oh, Tom, I'm not trying to tell you what to do, but we do have to act now, we don't find apartments we can afford every month. That's why you must take this job. Darling, I feel this is our last chance to live as we should. We've been apart so long that... that if we don't take this apartment... well, life is closing the door on us.”

“May, don't put it like that. We're not finished.”

“How else should I say it? That's how I feel. We must take the apartment.”

“If a guy who should have been—and will be—a big money fighter has to settle for being a lousy dishwasher, God might as well slam that door on me right now!”

May reached across the counter and slapped his braised cheek as she said, “It's blasphemy to talk of suicide, Thomas Cork!”

He stood up. Butch was walking slowly toward them behind the counter. Tommy said, “I seem to be wide open for a right tonight. Guess you might as well take your turn. May, I rushed here to tell you about how you'll be able to stop working. Live in a real apartment, maybe a hotel suite, have people waiting on you, for a change. For two years I been trying to get any kind of manager backing me. Now when I finally get this rich buff, you want me to give it up. That don't make sense, May.”

“God forgive me for striking you,” May said, sobbing. “You're talking dreams, Tom. What I'm saying is real, what we have to do now.”

“May, listen to me. If I can have one good year in the ring, one or two big paydays, I'll retire with ten or twenty grand in my kick. You're right, it is something I have to do now. I can't afford to wait even a week. Next time you see me I'll have a pocketful of dough, really set us up.”

Shaking her head, May covered her face with her hands and wept softly.

“It will come true this time, May, it has to—the luck of the Irish and this is the last throw of the dice. It's now or never for me, my last break.” Tommy wheeled around, saw Butch watching them, snarled, “What you want?”

“No trouble in here is what I want,” Butch said gently, his hands fondling a large soda bottle wrapped in a towel. He'd bounced plenty of men in his time—big men, even battled a few stick-up jaspers—but the look in Tommy's eyes made him uneasy. “I don't want you hitting her, in here.”

“I never struck May in my life. There's a fin on the counter, take out what I owe and give her the rest. And don't come around the counter or you'll get hurt.”

Tommy grabbed his suitcase, walked out fast.

TOMMY

He was dreaming. In the stuffy darkness of his narrow room it was impossible to see the smile on Tommy's rough face. He was seeing May when she was sixteen—the pretty, wistful face under the soft auburn hair, her body blossoming with delicate curves. He was reliving a scene on the stoop of the tenement. May's eyes were big with delight as she fondled the wrist watch he'd given her. Tommy, fighting amateur and bootleg pro bouts then, had won the match for flattening some wild kid in an uptown club in the first round. It was a night for firsts—the first watch May ever owned, the first any neighborhood girl had, and the first time she let him put his arm around her, right out on the stoop. May's hand wags on his back, gently stroking him... gently....

Arno was shaking Tommy, standing over the cot, careful not to touch the empty pint wine bottles on the floor. On a string hung across the room Tommy's ring togs were drying. Drunk or sober he always washed and took good care of his ring clothes. Jake was near the closed door, face screwed up with the smell of the room.

Tommy opened his eyes, tried to bring the darkness into focus. He sat up, holding his head with one hand, reached over with his left to snap on the one light. (In the old days when this had been the maid's room in the ancient apartment house, it wasn't thought necessary to give a servant more than one light. A window was out of the question.) Tommy's bloodshot eyes hit Arno's good overcoat,, traveled up to the plump face.

“How did you find me?”

From the door, Jake asked, “What makes you think you're hard to find, Pops?”

Tommy ran his tongue around his mouth, flexed his arms —he was sleeping in his heavy underwear—and belched loudly. “What time is it, Mr. Brewer?” Except for the big head he felt okay.

“A little after six p.m.” Arno daintily touched one of the dead soldiers on the floor with his shoe, said softly, “I see why you didn't call at my hotel.”

“Don't get the wrong idea,” Tommy said, his brains rusty as he tried to think straight. “I'm not a rumdum. I really meant to be at your hotel. But I had a... a... run-in with my wife, tried to lose myself in a bottle. I guess you're sour on me?”

Jake said, “Let's get out of here before I puke. I'd open the door but it smells worse in the hallway.”

Without turning his head, Arno said, “Shut up.” Brushing off a corner of the cot, he sat on the gray sheet. “I don't give up on things easily, Tommy. You ought to move out of this fleabag.”

Tommy split the soggy quiet of the room with another long belch. “Yeah? With what? I'm not living here out of choice, Mr. Brewer.”

Arno took out a tooled leather cigarette case, offered the pug one. When Tommy told him he didn't smoke, Arno lit a cigarette, blew out a thick cloud of smoke as if fumigating the room, said, “That's good. You certainly know more about training than I do. I don't mind you hitting the bottle, but not too often. If I take you on I expect you to be in shape—when I need you. Otherwise drinking is your own business.”

“I never touch the stuff,” Tommy mumbled. “It was the argument with my wife. She wants me to quit fighting.”

“That what you want, Irish?”

“Hell, no.”

“All right. As I told you last night, I have money, so managing fighters is merely a hobby with me. Sign with me and I'll pay your room and board, buy you some clothes, give you modest spending coin. But don't think I'm a sucker; it will be a loan. I'll get it back from your purses.”

“Know what I took down last night? Nineteen bucks!”

Arno shrugged. “Since it's my money and my hobby, let me worry about it. When you fight for me, you'll be well paid.” He pulled a folded contract from his pocket, then counted out two hundred dollars—an imposing pile of five-dollar bills. “I want you to sign this, after you read it. Legally I won't be your manager of record, for reasons I'll explain some other time. But this states that I'm staking you, buying a sort of interest in your career. You agree to give me twenty per cent of your purses until the money I loan you is paid. It's legal. Show it to a lawyer, if you wish. Take this money and pay your rent here, buy a suit, and be at my hotel, the Southside, at nine in the morning. We're leaving to train in the country for a few weeks. Buying that?”

“Yes sir! Listen, Mr. Brewer, you'll see I still got the stuff, the fastest left in the racket.”

Jake, standing by the door, laughed silently.

Arno got to his feet, knocked over one of the empty bottles. “Lay off the booze, for now. Don't let me down.”

“Don't you worry, Mr....”

“Cut the mister line. Call me Arno.”

“Don't you worry, Arno, I'll be on the ball,” Tommy said, getting out of bed, a comical little man in crumpled and stained underwear.

“We don't worry, Pops.” Jake's voice managed to sound sharp and cold in the stale air of the tiny room.

“Let's make that ten a.m. tomorrow,” Arno said, walking toward the door, ducking under the string on which Tommy's trunks were drying. “Give you time to buy some clothes. When we return to town you'll be staying at the hotel. I want you to look like a coming champ. Meantime, keep this quiet. I'll explain that later, too. Sign the contract, get yourself straight. I don't want a cent of my money spent on booze. We understand each other?”

“You bet. You can trust me, Arno. I'll be at the Southside tomorrow, ten o'clock.”

“Sharp,” Jake said, opening the door for Arno.

Outside in the hallway Jake whispered, “You shouldn't have given him so much dough. He'll drink himself stiff.”

“Don't talk loud,” Arno said. “Sure he'll drink. Is that bad? Main thing, he took the dough, he's into us.”

“But he hasn't signed the contract yet?”

“Leave the thinking to me. He'll sign.”

“But we're running low on dough? Two hundred...”

“Let me handle this end, you just start training. Run your legs off instead of your dumb mouth. There's an East Indian restaurant I want to try—once I get the stink of this dump out of my chest.”

Tommy got out his shower shoes, stuffed the money inside his underwear, and clopped down the hallway to the John. Returning to his room he locked the door, put the one chair against it, and counted the money. Then he put the bills in his underwear again and stretched out, slept for awhile.

He awoke an hour later and counted the money once more. It was still two hundred bucks. It wasn't a dream. For a split second he considered giving May a hundred and fifty for the apartment she wanted so badly, but dismissed the idea just as quickly. No point in risking Arno getting sore at him. He'd already goofed. Beside, within a couple of months he'd buy May a regular house if she wanted it.

He dressed and packed all his stuff, including the damp ring togs. It didn't take more than a few moments. Downstairs he paid the two week's rent he was behind, told the astonished and unshaven elderly man behind the desk he was moving. The cold night air took all the wine-sleep out of his head. He stopped at a laundry to leave his dirty clothes, opening the battered suitcase on the counter. The old woman running the shop insisted on a dollar deposit and Tommy flashed his roll, to spite her. He stopped for a fast cup of coffee and a buttered roll. The wall clock said it was twenty after seven, and he raced across town to a pawn shop which closed at eight. Here he purchased a decent suitcase for fifteen dollars and a small leather bag for six, and took out a suit and overcoat he'd put in pawn during the summer—as a means of safe storage. It cost him thirty-two dollars to redeem the clothes. He carefully packed all his things into the new bag, except the gym clothing, which he placed in the smaller bag.

Once outside, Tommy shoved his old suitcase into a comer trash basket, took a bus uptown to a shop near the gym where he bought new boxing shoes, socks, underwear, shirts, and a pair of cheap black dress shoes. He dropped into a coffeepot for supper, picked up a paper and put two dollars on a horse called Green Face running in the nightly trotter races. He had exactly ninety-eight dollars left, including two dollars from the nineteen Becker had paid him.

Tommy mailed May a ten spot and took a two dollar room at a Turkish bath. He sweated the last of the wine out in the steam room, swam in the ice water pool, left a call for eight in the morning, and fell into a happy sleep.

He was up before seven, took another swim, shaved, and dressed in his new clothes. The suit and coat were practically new, although he'd bought them months before. On the spur of a drunken Saint Patrick's-Day moment, Tommy had put a couple dollars on an impossible long shot named Loud Bean. (He'd thought it read Green.) When he sobered up, Tommy found he'd purchased the suit and overcoat. He had to hock them within the month.

After a big breakfast he walked over to the Southside, a modest, first-rate hotel, phoned, and went up to the room Arno was sharing with Jake. Tommy looked so good Arno stared at him with dismay. The men were dressing and after they packed their bags, they all went down to the car. Arno and Jake had breakfast while Tommy sat in the car. He remembered the contract, glanced through it and decided it was okay, signed it. He felt swell; the good clothes, the contract, and sitting in a flashy auto.

Jake took the wheel and after stopping while Arno shopped for the cans of Chinese food and special nuts and candies he was fond of, they left the city, driving north. Tommy sat up front while Arno dozed in the back seat or nibbled tiny bits of ginger. The only time Arno talked during the two-hour ride was to say, “Glad you laid off the rotgut, Tommy. You look sharp.”

“Told you I wasn't a lush. You'll see, I still got it. My legs aren't too bad, I'm not a bleeder, and my left is as fast as ever.” He went through the motions of breathing deeply. “Air smells sweet. You know, I haven't been to a training camp in years—since the time I trained for Robinson.”

Jake asked, surprised, “You was in with Sugar Ray?”

Tommy was just as startled. Everybody in the fight game knew that. “Sure. I was TKO'd in the eighth.” As an afterthought he added a moment later. “I was out-boxing him most of the way, was ahead on points. But he had too much experience for me. One punch took me out.”

“Soon as I saw you the other night,” Arno said, “despite the pasting you were taking, I told myself this fellow has the makings of a great fighter. You still have time to make it.”

“You bet,” Tommy said happily.

They drove to an old-time health resort which had a few customers during the summer. Now it was empty and the owner in Florida, but he had arranged for a local couple to keep the place open, cook and clean. The big house impressed Tommy, as did the barn with its old ring, heavy and light bags. All of it was set on the side of a small mountain, with a full view of the valley and a river covered with ice.

Tommy had a room of his own and while he was unpacking Jake came in. “Arno wants us to do some light sparring, before lunch. Tomorrow we start real training.”

“Sure. You done much fighting?”

“Naw, mostly amateurs—out West,” Jake said, talking in his hard clipped manner, as if cutting off each word with a razor.

“What's the deal with Arno?”

“What do you mean? What deal?” Jake asked slowly.

“What goes with him? I never saw a manager lay out dough like this. Cost a bundle to rent this set-up.”

“No deal. The guy is loaded and wants to be a fight manager. Anything wrong in that?”

“I'm all for it. What's he do for pork chops?”

“I never asked. Think he's retired, had a string of vending machines. What diff does it make?”

“None.”

“Pops, all we got to do is train regularly. Arno plans to build us up slowly. Mostly we'll fight in small out-of-town clubs and... He wants the contract. You sign it?”

“Aha.”

“Let me have it.”

“You managing me, too?” Tommy asked, pulling the contract from his pocket, tossing it on the bed.

“He told me to get it,” Jake said simply, picking it up and walking out of the room.

Tommy hung up the rest of his things, humming a pop tune, thinking, Jake isn't over-bright. Looks about twenty-three, twenty-four, should have been out of the amateurs long ago, if he's any good. He looks like a fighter, though, even if he knows from nothing. Never heard of me being in there with Robinson I All this talk about boxing in small clubs. What clubs are left? Hell, outside the Golden Gloves, not even amateur cards around. But if Arno is some retired business cat wanting to play at being a manager, I'll go along. Give me a chance to get back in shape.

Tommy took his ring things into the barn. Everything was neat and well-kept, but terribly old. Even the framed pictures on the walls were of fighters who'd been active before Tommy was born. The barn was unheated and Tommy undressed quickly. He didn't have any sweat pants and didn't want to wear his long underwear. He bandaged his hands and began working on the light bag to keep warm.

Wearing a heavy white turtleneck sweater under his overcoat and a ridiculous red beret, Arno walked in followed by Jake lugging a duffle bag. He took out his ring equipment and Tommy was impressed. His ring things were the best. Tommy, working on the bag, watched Jake undress and put on a sweat suit. Jake stripped big. Although a one hundred forty-five pounder he had the thick shoulders of a heavyweight, a thin waist, and sturdy legs. Tommy thought, He's built like LaMotta. Too much muscle, though. Probably a wild slugger who went over big in a hick amateur tournament.

After Jake warmed up by skipping rope, he and Tommy laced on heavy gloves and headguards. Sitting at the ringside, smoking an aromatic cigarette, Arno called up, “Want you boys to go about three rounds. Tommy, you tell me later what Jake does wrong.”

The moment Arno reached over and rang the bell Tommy realized there was little Jake did wrong. He was an excellent boxer with very fast hands and sure footwork. His defense was good and his left jab fast as Tommy's. He was tremendously strong and it was only at infighting, the little tricks of being up a man, feinting with his feet, spinning, that Tommy's greater experience showed.

When the round ended, Tommy walked around the ring slowly while Jake lounged against the ropes, breathing too hard. Tommy studied Jake's vaselined face, the lack of scars, nothing except the thickened nose and lean hard cast of his face as evidence he'd been in many rings. Tommy thought, One thing, he never learned all he knows in the amateurs. He's ring-wise, moves as gracefully as Conn used to. Must be something wrong. Probably hasn't a punch. Those big muscles don't mean a thing.

In the next round Tommy showed his class by crossing his right over Jake's left hook, slamming him in the gut. Jake clinched for a second to get his wind back. Jake tried another left and although Tommy was pulling back from the punch and it landed on the side of his headguard, it shook him. There was no doubting the wallop Jake packed in his left. In the middle of the round, Tommy decided to show off for Arno, suddenly switched to a southpaw stance. A short, whistling right landed flush on the side of Tommy's chin. He fell to the patched canvas—out cold.

Jake leaned against the ropes, grinned down at Arno; his white mouthpiece making the smile almost grotesque. Arno had jumped to his feet, anger on his fat face. Jake spit the mouthpiece into a gloved hand, said, “That does it. He's our boy.”

“Shut your damn face, you fool!” Arno said, climbing into the ring with difficulty, kneeling beside Tommy to remove his mouthpiece. “Think he heard you?”

“Come on, look at him. All he's hearing is the birdies. I was just testing.”

“He looks dead now, you idiot!”

“Leave him alone, he'll come around in a few minutes. Help me get his gloves off.”

When Tommy opened his eyes, he found himself propped on a ring stool, head resting on the faded padding of the ring corner ropes. Jake was banging away at the heavy bag, granting with pleasure each time his gloved fists slammed into the long bag. Arno was pressing a sponge full of snow and cold water to Tommy's face, held another at the back of his neck, watching the fighter's pale face with anxious eyes.

Tommy blinked, shook his head, tried to sit up. Arno held him back. “Easy now. Sit still.”

The buzzing deep in Tommy's head dropped to a dull little roar, then died. His eyes were out of focus. After a moment, Tommy tried to push the cold sponge from his forehead, muttered, “Did... he... cool me?”

Arno nodded.

Now clarity and steady strength rushed into Tommy. He pushed Arno aside and stood. “Let me walk around. I'll be okay.”

“Sit down and rest,” Arno said, pulling a flask from his hip pocket. “I have some good brandy here.”

Tommy shook his arms, as if trying to shake the gloves off, then sat down and shook his head. He gave Arno a sad smile. “I guess this sours you on me. Honest, this is the second time I've been clean-kayoed in my life. I've had fights stopped because I was out of shape but... Jeez, your boy can hit. With training gloves on, too!”

“I'm not soured on you. I...”

“You mean our deal is still on?”

“Of course. I know Jake can hit. Listen, you take a shower and get dressed. I'll be waiting for you up at the house. We need to have a talk. It's time I told you my plans.”

“Anything you say, Mr.... Arno.”

Arno walked down the few ring steps as if he was on a tightrope a mile high, took a belt of brandy. Tommy shadow-boxed for a few minutes, then jumped over the ropes to the ring apron, then to the floor. The jar when he landed completely cleared his head, although he still felt weak.

He walked over to Jake, watched him slug the heavy bag for a few seconds, then held out his gloved hands. Jake pulled his punching-bag gloves off, untied Tommy's heavy training gloves. “Sorry, Pops. I clipped you with a lucky one. You walked into my right.”

“It happens. You have a lot of stuff. Jake. A barrel full.”

“Thanks. Guess I'll go another round, then knock it off.”

After a shower, Tommy felt fine—almost. He ran up to the house and found Arno watching a Western on the small screen TV in the old living room. Arno had a bottle of Scotch and glasses, motioned for Tommy to take a glass. When Tommy hesitated, Arno poured him a big hooker, said, “Come on, it will relax you. Sit down.”

Tommy sipped the drink, although he never liked Scotch, told Arno, “You got a hell of a fine boxer in Jake.”

Arno motioned for him to keep his voice low, pointing toward the kitchen where the woman was making lunch. He whispered, “I know what I have in Jake.”

“I've been around, Arno. I've seen all the good welters, boxed with most of them. I've sparred with Cerdan, Graham, Olson, and battled Sugar Ray. Jake is not only a sharp boxer, but he's probably the hardest puncher I ever saw.”

Watching the TV Western out of the comer of his eye, Arno nodded, pleased. “Jake is not only very good but, what's even better, nobody knows about him. I've been bringing him along quietly. I'm capitalizing on the fact TV has killed the smaller clubs. In the old days I couldn't keep a Jake a secret. Now—I'm not going to cut in any of the fight mob, either. Same goes for you. When I manage a fighter, or any other business, it has to be all mine.”

The Scotch filled Tommy with a nice warmth. “Jake can take any welter around—Jordan, Akins. I'd bet on him taking most of the middleweights, too—Basilio, Fullmer, Webb.”

Arno nodded again, filled Tommy's glass. “I know that. When I finally spring Jake, it's going to be so big, so sensational the fight mob will have to let me in, on my own terms. I'm a gambler, and believe me, when Jake pops, I'll also make a betting killing.”

“That's playing it smart,” Tommy said, a little puzzled. “But how are you going to get Jake 'in'?”

“The reason I'm taking you on. Tommy, you're my key. You have the name. You train right, start getting a few bouts here and there. You'll have to piece yourself off to get the fights, but that's okay. That's my edge on the fight mob, money isn't important to me. This is also why I'm not your manager—on paper. Now, soon as you get to be a contender again, you'll agree to fight an unknown, take what seems like a soft touch.”

“Jake?”

Arno beamed. “You know Jake can take you, don't you, Tommy?”

“Well, I'm not in shape and he caught me trying to be cute. I... You want me to take a dive?”

“Would you do business?”

Tommy finished his drink and laughed. “Arno, I been a pro pug for about fifteen years. Pro means fighting for one thing—dough. I've gone into rings sick, hungry, and once with a busted hand. The glory bit has worn thin for me.”

Arno reached for the bottle but Tommy shook his head. Arno showed his strong even teeth in a grin, turned the TV down as the commercial came on. “I knew you were a smart cookie the moment I saw you, Cork. I admire a man like myself, who faces up to the facts of life, not the dreams. You won't regret it. I figure if you go into the tank, especially on TV, why, then they can't freeze us out. The fans all across the country will demand Jake fight the champion. I'll be in the driver's seat. Also, I have a couple of new angles to show the fight mobsters, that I'll tell you—in time. Once Jake is champ, then we call the tune, and you get all the big paydays you want. Jake might even take a fall for you, let you hold the crown for a while. You buying?”

“All the way,” Tommy said, holding out his hand.

Arno shook it. “Let's drink on that.”

“I've had enough,” Tommy said, only because too much Scotch made him sick. “Hey, when they going to have chow ready?”

“One thing we have to get squared away on—nobody is to know of this except us two. Not even Jake. I'll let him in on things later, when he has to know. But you must see that if anybody else knows, it queers our whole set-up.”

“Don't worry about me, I can be speechless when necessary. How soon do I start fighting?”

“When you're in shape. Like I told you, you're the key to the whole works. Take your time, you have to be right. Perhaps in a month or two.” Arno took out his wallet. “In the meantime, as per our agreement, I'll pay your room and board, give you twenty-five a week.” He handed Tommy two tens and a five. “I'm strictly a businessman, I'll keep track of what I loan you, start taking it from your first large purse. Okay?”

“I wouldn't want it no other way.”

The woman in the kitchen called out she was ready to put food on the table. Arno asked Tommy, “Will you go down to the barn and get Jake?”

“Sure.”

Arno winked, put a fat finger on his lips. As Tommy left the room, Arno turned up the TV to catch the end of the cowboy show, took a fast swig from the brandy flask in his pocket. He thought, I could sell the simple bastard the popcorn concession on the moon. Always amazes me, the sillier the line, the harder some mark falls. But a punchy fighter—hardly a workout for me.

DETECTIVE STEINER

Walt Steiner finished his tour of duty at four o'clock and was home watching an old movie on TV by a quarter to five. “Home” was an old-fashioned railroad flat of six rooms, three flights up, in a building which would have been condemned as an ancient tenement—if the area hadn't become a hangout for artists and writers, and young men with immature beards. The landlords found a mild boom on their hands and were quick to welcome the cafe espresso shops, happy the slum was now a second “Greenwich Village.”

Ruth had insisted upon taking the apartment. It didn't make a bit of sense to Walt. Between them they had an income of over ten thousand a year, why live in a roach-infested dump, not to mention the long hours he had put in painting and fixing up the place? Still, it was roomy. Ruth had her “den,” furnished with ugly white iron garden furniture, which pleased her for some unknown reason. (Actually it was most uncomfortable, but the wrought iron furniture was a good conversation “thing.” Friends would ask, “How can you possibly write on that table or sit in the hard chair?” Ruth would reply, the proper note of self-sacrifice in her voice, “Writing is an uncomfortable taskmaster.”) The walls of the apartment had conventional bull fight posters, several abstract oils, and framed photostats of checks from the New Yorker and Seventeen for the two stories Ruth had been paid for—in contrast to her yams in the little literary magazines where the “pay” was a few copies of the magazine.

The bedroom and living room were done in severe ebony modern and after a year or so, Walt almost liked the furniture. He also had his “den,” furnished with a battered bookcase and cracked leather couch which Ruth claimed his folks must have brought from Germany when they came over in 1908. On top of the bookcase were the cups and medals Walt had won as an amateur boxer. On the walls were pictures of Walt as a member of the Olympic boxing squad, of Captain Walt Steiner, coach of the 18th Air Force boxing team in Italy. Someplace around the room was a huge dusty scrapbook, the newspaper clippings already crumpling and yellow with age, full of pictures and stories about Walt when he was the Golden Gloves one hundred seventy-six-pound champion.

Although Walt still wore his white Olympic robe with the faded USA on its back—as a shower robe—he rarely opened his scrapbook, or looked at the pictures on the wall. Now and then, while watching TV fights, he would wonder if he'd been smart in turning down the money offers to turn pro—one manager had dangled a $3000 bonus. When reading of the large purses the champions made, Walt sometimes daydreamed of himself as the light heavyweight champ, perhaps fighting Archie Moore. And whenever he read about the money difficulties of Joe Louis and other greats, he was glad he had chosen to be a cop.

Walt did everything with a kind of Teutonic calm efficiency. He was steady but never spectacular. He had a mild sense of humor and an even milder imagination. In the ring he had fought a plodding dull fight, following the rules to the letter. You led with your left and crossed your right. Walt had been defeated in the finals of the National A.A.U. by a skinny Negro who did everything wrong. He clowned, dancing about the ring with his hands down, often led with his right, and told Walt jokes all during the bout. At the end of three puzzling rounds the colored fighter was puffing, obviously out of condition, while muscular Walt could have gone ten rounds, although badly outpointed.

Even now, when he was thirty-three years old and hadn't boxed in nine years, Walt was only seven pounds over his fighting weight, did stomach exercises every morning. He rarely ate sweets, didn't smoke, and drank only beer, except when Ruth gave a party and he'd take a few drinks to be sociable.

Watching the cowboy riding like crazy across the TV screen, Walt opened his shirt collar, rubbed his bull neck. He kept nervously glancing at his wrist watch. At five-twenty he began staring at the pink telephone. Ruth should be home about now, but he knew she wouldn't. She'd call and tell him about having to work late. Walt grinned bitterly. It was like the old gag in reserve, the cartoon of the boss with his secretary on his lap, phoning his wife and saying he was stuck in conference. Who was sitting in Ruth's lap this minute?

The trouble was, their whole life seemed to be in reverse these days. The other married men on the detective squad went home to have supper with their wives, talk about the funny or unusual things which had happened during the day, horse around with the kids. Walt came home to nothing. But most of the wives he'd met weren't as clever as Ruth, nor as pretty. They certainly couldn't edit a cosmetic trade magazine, write the moving little sketches Ruth was always starting—and never finishing. Some day, Walt was certain, if Ruth would only get with it, she would be a famous writer, at least a...

The doorbell rang. Walt jumped to his feet, relief in his big face. Ruth had stopped to shop, must have her hands full of packages, couldn't use her key. Walt opened the door to see a tall stooped man standing there. From the casual, expensive clothes, Walt thought he must be another of Ruth's “artistic” friends. The man asked, “Detective Walter Steiner?”

The deep, clear voice, vaguely jolted Walt's memory. The tall man's eyes raced to Walt's hip holster. Walt said, “That's me.”

“I hope you'll forgive my barging in like this. I'm Alvin Hammer, the television announcer. I missed you by minutes at the precinct house, couldn't find your number in the phone book. While I know this is suppertime, I'll only take a few minutes. I think you'll be interested in what I have to tell you.”

“We have an unlisted phone,” Walt told him, motioning for Hammer to come in. Depending on his tour, he always listened to Alvin describe the fights. He had imagined Alvin a huskier, older man.

Alvin took off his hat, opened his coat. He was impressed by the furniture, the oils and prints on the wall. Offering Walt a cigarette, he lit one himself, said, “I've come to you because I know of your interest in boxing. There's something, well, odd, going on. I don't quite know how to handle it. I may be sticking my nose into something. I mean, I'm not sure it's a police matter.”

Crossing the room to turn off the cowboy—now slugging another cowhand like crazy—on TV, Walt asked, “What's troubling you?”

“Do you know a fighter named Irish Tommy Cork?”

“Cork? Isn't he the old welter who came out with his eye badly cut, flattened the other guy?”