David Weber

Oath of Swords

(War God – 1)

Epigraph

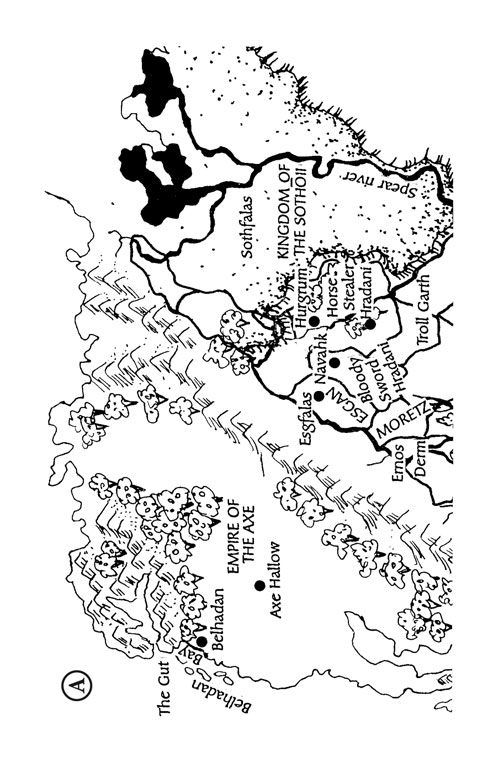

hradani

(hrä-dä-ne) n. (1) One of the original Five Races of Man, noted for foxlike ears, great stature and physical strength, and violence of temperament. (2) A barbarian or berserker. (3) Scum, brigand. adj. (1) Of or pertaining to the hradani race. (2) Dangerous, bloodthirsty or cruel. (3) Treacherous, not to be trusted. (4) Incapable of civilized conduct. [Old Kontovaran: from hra, calm + danahi, fox.]

Rage, the

(rag) n. Hradani term for the uncontrollable berserk bloodlust afflicting their people. Held by some scholars to be the result of black sorcery dating from the Fall of Kontovar (q.v.).

Strictures of Ottovar

(strik-cherz uv äh-to-vär) n. Ancient code of white wizardry enforced by Council of Ottovar in pre-Fall Kontovar. The Strictures are said to have prohibited blood magic or the use of sorcery against non-wizards, and violation of its provisions was a capital offense. It is said that the wild wizard (q.v.) Wencit of Rūm, last Lord of the Council of Ottovar prior to the Fall, still lives and attempts to enforce them with the aid of the Order of Semkirk.

– New Manhome Encyclopedic Dictionary of Norfressan Languages,

Chapter One

He shouldn’t have taken the shortcut.

Bahzell Bahnakson realized that the instant he heard the sounds drifting down the inky-dark cross corridor. He’d had to keep to the back ways used only by the palace servants-and far more numerous slaves-if he wanted to visit Brandark without the Guard’s knowledge, for he was too visible to come and go openly without being seen. But he shouldn’t have risked the shortcut just to avoid the more treacherous passages of the old keep.

He stood in an ill-lit hall heavy with the stink of its sparse torches (the expensive oil lamps were saved for Churnazh and his “courtiers”), and his mobile, foxlike ears strained at the faint noises. Then they flattened in recognition, and he cursed. Such sounds were none of his business, he told himself, and keeping clear of trouble was. Besides, they were far from the first screams he’d heard in Navahk . . . and there’d been nothing a prince of rival Hurgrum could do about the others, either.

He squeezed his dagger hilt, and his jaw clenched with the anger he dared not show his “hosts.” Bahzell had never considered himself squeamish, even for a hradani, but that was before his father sent him here as an envoy. As a hostage, really, Bahzell admitted grimly. Prince Bahnak’s army had crushed Navahk and its allies, yet Hurgrum was only a single city-state. She lacked the manpower to occupy her enemies’ territories, though many a hradani chieftain would have let his own realm go to ruin by trying to add the others to it.

But Bahnak was no ordinary chieftain. He knew there could be no lasting peace while Churnazh lived, yet he was wise enough to know what would happen if he dispersed his strength in piecemeal garrisons, each too weak to stand alone. He could defeat Navahk and its allies in battle; to conquer them he needed time to bind the allies his present victories had attracted to him, and he’d bought that time by tying Churnazh and his cronies up in a tangle of treaty promises, mutual defense clauses, and contingencies a Purple Lord would have been hard put to unravel. Half a dozen mutually suspicious hradani warlords found the task all but impossible, and to make certain they kept trying rather than resorting to more direct (and traditional) means of resolution, Bahnak had insisted on an exchange of hostages. It was simply Bahzell’s ill fortune that Navahk, as the most powerful of Hurgrum’s opponents, was entitled to a hostage from Hurgrum’s royal family.

Bahzell understood, but he wished, just this once, that he could have avoided the consequences of being Bahnak’s son. Bad enough that he was a Horse Stealer, towering head and shoulders above the tallest of the Bloody Sword tribes and instantly identifiable as an outsider. Worse that Hurgrum’s crushing victories had humiliated Navahk, which made him an instantly hated outsider. Yet both of those things were only to be expected, and Bahzell could have lived with them, if only Navahk weren’t ruled by Prince Churnazh, who not only hated Prince Bahnak (and his son), but despised them as degenerate, over-civilized weaklings, as well. His cronies and hangers-on aped their prince’s attitude and, predictably, each vied with the other to prove his contempt was deeper than any of his fellows’.

So far, Bahzell’s hostage status had kept daggers out of his back and his own sword sheathed, but no hradani was truly suited to the role of diplomat, and Bahzell had come to suspect he was even less suited than most. It might have been different somewhere else, but holding himself in check when Bloody Swords tossed out insults that would have cost a fellow Horse Stealer blood had worn his temper thin. He wondered, sometimes, if Churnazh secretly wanted him to lose control, wanted to drive Bahzell into succumbing to the Rage in order to free himself from the humiliating treaties? Or was it possible Churnazh truly believed his sneer that the Rage had gone out of Hurgrum, leaving her warriors gutless as water? It was hard to be sure of anything where the Navahkan was concerned, but two things were certain as death. He hated and despised Prince Bahnak, and his contempt for the changes Bahnak had wrought in Hurgrum was boundless.

That Bahzell understood, after a fashion, for he, too, was hradani. He understood the craving for battle, the terrible hot hunger of the Rage, and he shared his people’s disdain for weakness. But he had no use for blind stupidity, either, and what he couldn’t understand was how Churnazh could continue to think Bahnak a fool. Churnazh might sneer at Hurgrum as a city of shopkeepers who’d forgotten how to be warriors, but surely even he didn’t think it had been pure luck that Hurgrum had won every battle!

Of course, as a lad Bahzell himself had questioned some of his father’s more peculiar notions. What need did a warrior have of reading and writing or arithmetic? Why worry about tradesmen and artisans or silly things like laws governing money-lending or property rights? Where was the honor in learning to hold formation instead of charging forward to carve your own glory from the enemy’s ranks? And-despite himself, Bahzell smiled a little in memory, even now-surely bathing every single week would ruin a man’s constitution!

But he questioned no more. Hurgrum’s army hadn’t simply defeated five times its own numbers; it had slaughtered them and driven their survivors from the field in a rabble, and it had done so because it fought as a disciplined unit. Because its maps were accurate and the commanders of its fast-marching contingents, or at least their aides, could read the orders their prince sent them and close in upon their enemies in coordinated attacks. And because it was uniformly trained, because its warriors did keep formation and were equipped with weapons of its own city’s manufacture from the hands and forges of the “shopkeepers” Churnazh despised.

That was a lesson even other Horse Stealers could appreciate, which explained the new allies Hurgrum was gathering in, but since seeing Navahk, Bahzell had come to recognize an even more enduring side of his father’s accomplishments. Prince Bahnak’s native city had been bad enough before he came to power, yet Navahk was worse than Hurgrum had ever been. Far worse. It was a place of noisome streets cluttered with garbage, night soil, and small dead animals, heavy with the stench of unwashed people and waiting pestilence, all presided over by swaggering bullies in the colors of the prince who was supposed to rule his people, not plunder them himself!

But, then, Churnazh had been a common brigand before he joined the Navahkan army, rose through the ranks, and seized the throne, and he was proud of the brute strength that proved his right to rule. Strength Bahzell could appreciate; weakness was beneath contempt, and he knew his father couldn’t have held his own throne if his warriors thought for one moment that he was a weakling. But in Churnazh’s eyes, “strength” rested upon terror. His endless wars had made Navahk the most feared of all the Bloody Sword cities, yet Navahk herself was terrified of him . . . and his five sons were even worse than he.

All of which explained why the last thing a hostage from Hurgrum had any business doing was standing in this hall listening to screams and even considering intervening. Besides, whoever was screaming was only another Bloody Sword, and, with the noteworthy exception of Brandark, there wasn’t a Bloody Sword worth the time to send him to Phrobus, much less risk his own life for.

Bahzell told himself that with all the hardheaded pragmatism he could summon . . . then swore vilely and started down the unlit corridor.

***

Crown Prince Harnak grinned as he smashed his fist into Farmah’s face yet again. Her gagged scream was weaker and less satisfying than it had been, but his metal-reinforced gauntlet cut fresh, bleeding gashes, and he felt a sensual thrill of power even greater than he’d felt when he raped her.

He let her slip to the floor, let her try to crawl away with her arms bound behind her, then kicked her in the ribs. The shredded chemise wadded into her mouth muffled her gurgling shriek as his boot smashed her into the stone wall, and he laughed. The bitch. Thought she was too good for a prince of the blood, did she? Well, she’d learned better now, hadn’t she?

He watched her curl in a beaten ball and savored her hopeless terror. Rape was the one crime that might turn even his father’s men against him, but no one would ever know who’d had this slut. When they found her body and saw all the things he’d done-and still looked forward to doing-they’d assume exactly what he wanted: that someone taken by the Rage’s blood frenzy had slaughtered her like a sow, and-

An abrupt explosion of rending wood shattered his hungry anticipation and snatched him around in shock. The long abandoned sleeping chamber’s locked door was thick, as stout and well built as any door in Navahk was likely to be, but its latch simply disappeared in a cloud of splinters, and the door itself slammed back against the wall so hard one iron hinge snapped. Harnak jumped back in instant panic, mind already racing for a way to bribe or threaten his way out of the consequences of discovery, but then his eyes widened as he saw who stood in the opening.

That towering figure could not be mistaken for anyone else, but it was alone, and Harnak snarled in contemptuous relief as the intruder glanced at the naked, battered girl huddled against the wall. Big he might be, but Bahzell of Hurgrum was no threat. The puling, puking coward had hidden behind his “hostage” status for over two years, swallowing insults no warrior would let pass . . . and he was armed only with a dagger, while Harnak’s sword lay ready on the rotting bed. Bahzell would never raise his hand to the heir to Navahk’s throne-especially if it meant matching eighteen inches of steel against forty!-and even if he carried the tale to others, no one in Navahk would dare take his word over that of a prince of the blood. Particularly if Harnak saw to it that Farmah had vanished before the Horse Stealer could get back with help. He straightened his back with an automatic, arrogant snarl, gathering his scattered wits to order the intruder out, but the words died unspoken as Bahzell’s eyes moved back to him. There was something in them Harnak had never seen before . . . and Bahzell wasn’t stopping in the doorway.

A ball of ice froze in Harnak’s belly. He had time to feel one sudden stab of terror, to abandon his swaggering posture and leap desperately for his sword, and then an iron clamp seized him by the throat. Shouting for help would have done him no good-he’d chosen this spot so no one would hear his victim’s screams-but he never got the chance to try, for his cry died in a wheezing gurgle as the clamp lifted his toes from the floor. He writhed and choked, beating at Bahzell’s wrist with his gauntleted hands, and then another hand-not a clamp, this one, but a spiked mace-crashed into his belly.

Harnak screamed as three ribs snapped. The sound was faint and strangled . . . and dwarfed by the sound he made when a knee like a tree trunk smashed up between his legs.

His world vanished in agony so great he hardly noticed the mace crashing into his belly again. And then again and again and again. But he retained enough awareness to realize what was happening as Bahzell released his throat at last. The choking hand clasped the nape of his neck instead. Another hand caught his belt, and Crown Prince Harnak of Navahk screamed in terror . . . until he smashed face-first into the dirty little chamber’s wall and the impact cut his shriek off like a knife.

He oozed down the stone, smearing it with red, and Bahzell snarled and started forward to finish the job. The Horse Stealer’s muscles quivered as fury snapped and sputtered through them, but sanity still flickered, and he made himself stop. He closed his eyes and inhaled deeply, fighting back the red haze. It wasn’t easy, but the killing madness ebbed without quite passing over into the Rage, and he shook himself. He opened his eyes once more and looked down, grimacing at the knuckles he’d split on his enemy’s metal-studded leather jerkin, then turned to Harnak’s latest victim.

She writhed away in terror, too battered and beaten to realize he wasn’t Harnak, but then she felt the gentleness of his touch and whimpered.

“There, lass. There,” he murmured, bitterly aware of how useless the soothing sounds were yet making them anyway, and her frantic struggles eased. One eye opened, staring fearfully up at him, but the other was swollen shut, and the cheek below it was clearly broken.

He touched her hair gently, and disgust filled him as he recognized her cut and bloody face. Farmah. Who but Harnak-or his brothers-would rape a mere girl supposedly under his own father’s protection?

He lifted her, and bleak hate filled his eyes at her pain sound when broken ribs shifted. Her hands were bound behind her, and fresh contempt snarled through him as he recalled Harnak’s swaggering bluster about courage and hardihood. Courage, it seemed, required a “warrior” to bind a teenaged girl half his size to be certain she was helpless before he raped her and beat her bloody!

He eased her into a sitting position on a battered old chest against the wall. It was filthy, but the only other furnishing was the bed Harnak had raped her upon. She shuddered in terror and pain, yet she leaned forward to help as he cut the cord that had flayed her wrists raw and plucked the wad of cloth from her mouth. Returning intelligence flickered in her good eye. “Thank you, M’lord,” she whispered. “Thank you! ”

Her hand rose and squeezed his wrist with surprising strength. Or perhaps not so surprising, for she, too, was hradani, however slim and delicate she might be compared to Bahzell.

“Hush, girl. Don’t be thanking me,” Bahzell rumbled, and looked away from her nakedness in sudden embarrassment. He spied Harnak’s discarded cloak and scooped it up, averting his eyes as he held it out to her, and her sound as she took it was trapped between a sob of pain and shame and a strange, twisted ghost of a laugh.

It snarled deep inside Bahzell, that sound, striking fresh sparks of fury. He bought a few moments to reassert control by ripping a length of cloth from Harnak’s none too clean shirt and wrapping it around his bleeding knuckles, but the delay was little help, and his hand itched for his dagger once more as he glared down at Harnak. Rape. The one crime not even the Rage could excuse, even in Navahk. Hradani women had enough to endure without that, and they were too precious to abuse so, for they alone were immune to the Rage, the guardians of what little stability most hradani tribes could cling to.

“Lillinara must have sent you.” Farmah’s slurred words sent his ears flat once more, and he sketched an instant, instinctive warding gesture. She huddled in Harnak’s cloak, shaken by pain and reaction, and used a scrap of her torn clothing to wipe at the blood trickling from her nose and split lips.

“Wish me no ill fortune, lass. No good ever came of mixing in the gods’ business, and it’s Phrobus’ own tangle we’re in now, the both of us,” he muttered, and Farmah nodded in understanding.

Hradani notions of justice were harsh. They had to be for a people afflicted by the Rage, and the universal penalty for rape was castration and then to be drawn and quartered. But Harnak wasn’t just Churnazh’s son; he was his eldest son, heir to the throne, and ten years of Churnazh’s rule had made it plain the law did not apply to him or his. Farmah knew that better than most, for her father and elder brother had died at the hands of an off duty Guard captain. Everyone knew Churnazh had borrowed heavily from her father, but the prince had accepted his captain’s claim of the Rage and pardoned him, and somehow the debt-the money which might have meant Farmah’s livelihood or means of flight-had simply vanished. Which was how she came to find herself living under Churnazh’s “protection” as little more than a slave.

“Is-is he alive?” she asked weakly.

“Um.” Bahzell gave the limp body a brutal kick, and it flopped onto its back without even a groan. “Aye, he’s alive,” he grunted, grimacing down at the ruined face and watching breath bubble in the blood from its smashed nose and lips, “but how long will he stay that way? There’s the question.” He knelt, and his jaw tightened as he touched an indentation in Harnak’s forehead. “He’s less pretty than he was, and I’m thinking he hit the wall a mite hard, but he’s a head like a boulder. He might live yet, Krahana take him.”

The Horse Stealer sank back on his heels, fingering his dagger. Cutting a helpless throat, even when it belonged to scum like this, went hard with him. Then again, a man had to be practical. . . .

“Chalak saw him take me,” Farmah said weakly behind him, and he spat a fresh oath. Finishing Harnak might protect him , but if the prince’s brother knew his plans for Farmah, Harnak’s death would only make her hopeless situation still worse. Chalak might keep quiet, since Harnak’s elimination would improve his own chance for power, yet he was only Churnazh’s fourth son. It was unlikely Harnak’s removal would profit him significantly . . . but identifying his brother’s killer to their father certainly would.

The Horse Stealer stood and glared down at the motionless body while his mind raced. Killing Harnak wouldn’t save Farmah, and that meant it wouldn’t help him , either. Enough torture would loosen any tongue, and Churnazh would apply the irons himself. He’d like that, even if he hadn’t lost his son. So unless Bahzell was prepared to cut the girl’s throat as well as Harnak’s . . .

“How badly are you hurt, lass?” he asked, turning to her at last. She looked back mutely, and he waved a hand in a gesture that mixed impatience with apology. “We’re both dead if we stay, girl, whether he lives or dies. If I get you away, can you stay on your feet to run?”

“I-” Farmah looked back down at Harnak and shivered, then stiffened her shoulders and nodded as her own thoughts followed his. “I can run. Not fast, M’lord, but I can run,” she said hoarsely. “Only where could I run to? ”

“Aye, there’s the question.” Bahzell gave Harnak another kick, feeling her watch him in silence, and the look of trust in her one good eye made him feel even worse. He wished her no ill-fortune, but he couldn’t help wishing he’d never heard her screams, and he knew too well how misplaced her trust might be against the odds they faced. But counting the odds never shortened them, and he sighed and shook himself. “I’m thinking there’s just one place, lass-Hurgrum.”

“Hurgrum? ”

He smiled sourly at the shock in her voice, for if one thing was certain it was that he couldn’t return to Hurgrum. There’d be hell enough to pay over this even if Harnak lived; if the bastard died, Churnazh was certain to outlaw Bahzell for breaking hostage bond. He might well do so even if Harnak lived-gods and demons knew he’d seemed happy enough to let others try to provoke Bahzell into something which would let him do just that! And if the Bloody Swords outlawed him and he returned to his father’s court, the fragile balance holding the armies from one another’s throats would come down in ruins.

“Aye, Hurgrum,” he said. “But that’s for you, lass, not me.” He turned away from Harnak, doubts banished by action, and lifted her in his arms. “I came this way to avoid people. Let’s be hoping the two of us don’t meet anyone else on our way out-and that no one finds this bastard before we’re gone.”

Chapter Two

Bahzell moved swiftly down the ill-lit halls despite his burden. Churnazh’s “palace” was a half-ruinous rabbit warren whose oldest section had been little more than a brigand’s keep, built in a swampy bend of the small Navahk River as a place to lie up and count loot. Its newer sections included a few straighter, wider passages-evidence of days when Navahk’s rulers had at least aspired to better things-but the present prince’s notions of maintenance left much of his palace’s crumbling core dangerously unsafe.

Bahzell knew that, but it was always best to know the lay of the land, and after two years, he’d learned the palace as well as any of the slaves and servants who toiled within it. Now he used that knowledge to pick a circuitous route that avoided sentries and well traveled areas, and he made it almost all the way to his assigned chambers before he heard the sound of feet.

He swore softly but with feeling, for he couldn’t have picked a worse place to meet someone. The brisk footsteps clattered down a cross passage towards the last four-way intersection before his rooms, and the bare corridor behind him offered no concealment. But at least it sounded like a single person, and he set Farmah down and drew his dagger in a whisper of steel.

The feet pattered closer. They reached the intersection, and Bahzell leapt forward-only to jerk himself up short as his intended victim jumped back with a squeak of panic.

“M-M’lord?” the middle-aged woman quavered, and, despite the situation, Bahzell grinned. Her eyes were glued to the steel gleaming in his hand, and she sounded justifiably terrified, but she wasn’t running for her life. Which she would have been, if she hadn’t recognized him. Churnazh’s servants had the reactions of any other terrorized and abused creatures, and it had taken Bahzell months to convince them he wouldn’t hurt them; now this single moment made all his efforts worthwhile.

“I’d no mind to frighten you, Tala,” he said mildly as he lowered his dagger. The woman who would have been the palace’s housekeeper in Hurgrum (here she was simply one slave among many, and more exposed to her “betters’ ” wrath than most), drew a deep breath at his pacific tone and opened her mouth . . . just as Farmah stepped waveringly out from behind him.

“Farmah! ” Tala gasped, and leapt forward as the girl’s legs began to give. Only Tala’s arms kept her from collapsing, and the housekeeper gasped again as she realized how badly hurt Farmah was. Her eyes darted back to Bahzell, and he winced at the sudden, horrified accusation-the look of betrayal-in them. Yet he couldn’t blame her for her automatic assumption, and the accusation vanished as quickly as it had come. The horror remained, but fury replaced the betrayal, and her ears flattened.

“Who, M’lord?” she hissed. “Who did this?!”

“Harnak,” Farmah answered for him, resting the less injured side of her face against Tala’s shoulder, and the protective arms tightened about her. Tala looked into Bahzell’s eyes, searching for confirmation, and her own face tightened as he nodded. She started to speak again, then pressed her lips together and handed Farmah back to him.

She darted back to the intersection without a word and looked both ways, then beckoned him forward, and he sighed with relief as he scooped the girl back up and followed her.

Tala led the way to his chambers like a scout, then closed the outer door behind him and leaned against it to watch him deposit Farmah gently in a chair. Her expression was grim, but she showed no surprise when he shrugged out of his tunic, squirmed into a padded buckram aketon, and lifted his scale shirt from its rack. He drew it on and reached up for his sword, looping the baldric over his head and settling the hilt against his left shoulder blade, and Tala cleared her throat.

“Is he dead, M’lord?” Her voice was flat.

“He was breathing when I left him. Now?” Bahzell shrugged, and she nodded without surprise.

“I was afraid of this. He’s been after her so long, and-” Tala closed her mouth and shook her head. “How can I help, M’lord?”

Bahzell shook his head quickly, his face grim. “You’d best think what you’re saying, Tala. If he dies yet, or if we’re caught inside the walls-”

“If you’re caught, it won’t matter whether I helped you or just didn’t call the Guard myself.” Her voice was bleak as she looked at Farmah, huddled brokenly in the chair and little more than half-conscious. “That could be me, M’lord, or my daughter, if I’d been fool enough to have one.”

Bahzell frowned, but she was right. He’d already put her at risk simply by crossing her path, and he needed all the help he could get.

“Clothes first,” he said, and Tala nodded, accepting his acceptance. “I’ve naught that would fit her, and if anyone sees that cloak-”

“I understand, M’lord. We’re close enough in size my clothes would do. And then?”

“And then forget you ever saw us. I’m thinking it’s the servants’ way out for us.”

“Can she walk?” Tala asked bluntly, and Farmah stirred.

“I can walk.” Tala eyed her skeptically, and she straightened in the chair, one arm pressed to her side to cradle broken ribs. “I can ,” she repeated, “and I have to.”

“But where can you- No.” Tala cut herself off and shook her head. “Best I don’t know any more than I must.”

“Aye, for all our sakes,” Bahzell agreed grimly, and began stuffing items into a leather rucksack, starting with the heavy purse his father had sent with him.

“Very well, M’lord. I’ll be as quick as I can.”

Tala slipped out, closing the door behind her, and Bahzell worked quickly. He could take little, and he made his choices with ruthless dispatch, watching Farmah from the corner of one eye as he packed. She listed sideways in the chair, no longer holding herself erect to prove her strength to Tala, and he didn’t like the way she was favoring her right side. Something broken in there, and gods only knew what other damage she’d suffered. He admired her courage, but how far could she walk? And how quickly, when Churnazh’s men would be after them a-horseback within hours?

He pushed the worry aside as best he could and buckled the rucksack, then took his steel-bowed arbalest from the wall. (That was one more thing for Churnazh to sneer at-what sort of a hradani relied on arrows or bolts instead of meeting his enemies hand to hand?) Bahzell had hostage right to carry his personal weapons whenever he chose, but one sight of the arbalest by any sentry would raise questions he dared not answer, and he hesitated, loath to abandon it, then whirled as the door opened silently once more.

It was Tala, clothing bundled under her arm. She paused if to speak when she saw him holding the arbalest, then shook her head and crossed quickly to Farmah and helped her up from the chair. The door of the inner bedchamber closed behind them, and Bahzell laid the arbalest aside with regret. Their chance of getting as far as the city gate unchallenged was already so slight as not to exist; adding more weight to the odds would be madness.

He shrugged to settle his armor and began to pace. No one was likely to stumble over Harnak, but every second increased the chance of his regaining consciousness and raising the alarm himself. Once that happened-

Bahzell pushed the thought aside with his worries over Farmah’s strength. There was nothing he could do if it happened; best to concentrate on what to do if it didn’t, and he rubbed his chin and shifted his ears slowly back and forth as he thought. The immediate problem was escaping the city, but after that he still had to get Farmah to Hurgrum somehow, and how was he to do that when he himself dared not enter Hurgrum’s territory? He could think of only one way, but with Farmah’s injuries and-

He turned as the bedchamber door opened once more and Farmah stepped through it. Her movements were slow and obviously painful but stronger than he’d dared hope, and Tala followed her with a worried expression.

The housekeeper had done well, Bahzell thought. It would take an observant eye to realize the plain gray gown was just too large, its hem just too short for Farmah, and the extra girth helped hide the bandages Tala had bound tight about her ribs. Its long, full sleeves hid the bruises and rope burns on the girl’s arms, as well, and Tala had dressed her hair, but nothing could hide the marks on her face. The blood had been washed away, and the cuts no longer bled, yet they were raw and ugly, and her bruises, especially the ones on her broken left cheek, were dark and swelling.

Farmah felt his gaze and touched her face.

“I’m sorry, M’lord,” she began wretchedly, and he felt her shame at her ugliness, her knowledge that some, at least, of those cuts would be scars for life and that anyone who saw them now would guess instantly what had happened to her, “but-”

“Hush, lass! It’s no fault of yours.” He glanced at Tala. “I’m thinking a hooded cloak might help,” he began, “and-”

“Indeed it might, M’lord,” Tala agreed, raising her arm to show him the cloak draped across it, “and I’ve had another thought or two, as well.”

“You’d best not be getting any deeper into this,” Bahzell objected, and the housekeeper snorted.

“I’m deep enough to drown already, M’lord, so save your worry for things you can change.” She was old enough to be Bahzell’s mother, and her tart tone was so like his old nurse’s that he grinned despite his tension. It seemed Churnazh had failed to crush at least one of his slaves completely, after all.

“Better,” Tala said, and folded her arms beneath her breasts. “Now, M’lord, about this plan of yours. If the pair of you try to leave together, you’ll be challenged by the first guard you meet.”

“Aye, that’s why-”

“Please, M’lord!” Her raised hand shut his mouth with a snap. “The point is that you don’t have to leave together. All the servants know how you creep in and out to visit Lord Brandark.” His eyes widened, and she shook her head impatiently. “Of course they do! So if they see you, they’ll assume that’s all you’re doing and look the other way, as always. And the guards are less likely to challenge you if you’re by yourself, as well. True?”

“Aye, that’s true enough,” he admitted slowly.

“In that case, the thing to do is for you to go out through the back ways while Farmah walks right out the front gate, M’lord.”

“Are you daft?! They’ll never let her pass with that face, woman! And if they do, they’ll guess who marked her the moment someone finds Harnak!”

“Of course they will.” Tala glared up at his towering inches and shook her head. “M’lord,” she said with the patience of one addressing a small child, “they’ll guess that anyway when they find her missing, so where’s the sense in pretending otherwise when leaving separately gives you both the chance to pass unchallenged, at least as far as the city gate?”

“Aye,” Bahzell rubbed his chin once more, “there’s some sense in that. But look at her, Tala.” Farmah had sagged once more, leaning against the door frame for support. She stiffened and forced herself back upright, and he shook his head gently. “It’s nothing against you, Farmah, and none of your fault, but you’ll not make the length of the hall without help.”

“No, M’lord, she won’t . . . unless I go with her.” Bahzell gaped at the housekeeper, and Tala’s shrug was far calmer than her eyes. “It’s the only way. I’ll say I’m taking her to Yanahla-she’s not much of a healer, but she’s better than the horse leech they keep here for the servants!”

“And if they ask what’s happened to her?” Bahzell demanded.

“She fell.” Tala snorted once more, bitterly, at his expression. “It won’t be the first time a handsome servant wench or slave has ‘fallen’ in this place, M’lord. Especially a young one.” Her voice was grim, and Bahzell’s face tightened, but he shook his head once more.

“That may get you out, but it won’t be getting you back in, and when they miss Farmah-”

“They’ll miss me, too.” Tala met his gaze with a mix of desperation and pleading. “I have no one to keep me here since my son died, and I’ll try not to slow you outside the city, but-” Her voice broke, and she closed her eyes. “Please , M’lord. I’m . . . I’m not brave enough to run away by myself.”

“It’s no sure thing we’ll have the chance to run,” Bahzell pointed out. Her nod was sharp with fear but determined, and he winced inwardly. Fiendark knew Farmah alone was going to slow him, and if Tala was uninjured, she was no spry young maid. He started to refuse her offer, then frowned. True, two city women would be more than twice the burden of one, under normal circumstances, but these weren’t normal.

He studied her intently, measuring risk and her fear against capability and the determined set of her shoulders, and realized his decision was already made. He couldn’t leave her behind if she helped Farmah escape, and her aid would more than double their chance to get out of the palace. Besides, the girl would need all the nursing she could get, and if he could get the two of them to Chazdark, then he could-

His eyes brightened, and he nodded.

“Come along, then, if you’re minded to run with us. And I’ll not forget this, Tala.” She opened her eyes, and he smiled crookedly. “I’m thinking my thanks won’t matter much if they lay us by the heels, but if they don’t, I’m minded to send Farmah to my father. She’ll be safe there-and so will you.”

“Thank you, M’lord,” Tala whispered, and he wondered if he would ever have had the courage to trust anyone after so many years in Navahk. But then she shook herself with some of her old briskness and touched his arbalest with a faint smile. “You seemed none too happy to leave this behind, M’lord. Suppose I bundle it up in a bag of dirty linen and have one of the serving men carry it around to meet you outside the palace?”

“Can you trust them?” Bahzell asked, trying to hide his own eagerness, and her smile grew.

“Old Grumuk wanders in his mind, M’lord. He knows where the servants’ way comes out-he taught it to me himself, before his wits went-but he’ll ask no questions, and no one ever pays any heed to him. I think it’s safe enough. I’ll pass the word to him as we leave; by the time you can make your way out, he’ll be waiting for you.”

***

The creeping trip through the palace’s decaying core took forever. The slaves who used the passages to sneak in and out for what little enjoyment they might find elsewhere had marked them well, once a man knew what to look for, but Bahzell had never tried them armored and armed and they’d never been built for someone his size in the first place. There were a few tight spots, especially with the sword and rucksack on his back, and two moments of near disaster as teetering stone groaned and shifted, but it was the time that truly frightened him. Likely enough Harnak would never wake again, given that dent in his skull, but if he did, or if he was found, or if Tala and Farmah had been stopped after all-

Bahzell lowered his ears in frustration and made himself concentrate on his footing and how much he hated slinking about underground at the best of times. That was a more profitable line of thought; it gave him something to curse at besides his own stupidity for mixing in something like this. Fiendark only knew what his father would have to say! The world was a hard place where people got hurt, and the best a man could do was hope to look after his own. But even as he swore at himself, he knew he couldn’t have just walked away. The only thing that truly bothered him-aside from the probability that it would get him killed-was whether he’d done it to save Farmah or simply because of how much he hated Harnak. Either was reason enough, it was just that a man liked to feel certain about things like that.

He reached the last crumbling passage and brightened as he saw daylight ahead, but he also reached up to loosen his sword in its sheath before he crept the last few yards forward. If Tala had been stopped, there might already be a company and more of the Guard waiting up ahead.

There wasn’t. Steel clicked as he slid the blade back home, and the aged slave squatting against a moss-grown wall looked up with a toothless grin.

“And there ye be, after all!” Old Grumuk cackled. “Indeed, an’ Tala said ye would! How be ye, M’lord?”

“Fine, Grumuk. A mite muddy about the edges, but well enough else.” Bahzell made his deep, rumbling voice as gentle as he could. The old man was the butt of endless blows and nasty jokes, and his senile cheerfulness could vanish into whimpering, huddled defensiveness with no warning at all.

“Aye, them tunnels uz always mucky, wasn’t they, now? I mind once I was tellin’ Gernuk-or were it Franuzh?” Grumuk’s brow wrinkled with the effort of memory. “No matter. ’Twere one or t’other of ’em, an’ I was telling him-”

He broke off, muttering to himself, and Bahzell stifled a groan. The old man could run on like this for hours, filling even the most patient (which, Bahzell admitted, did not include himself) with a maddening need to shake or beat some sense into him. But there was no longer any sense to be beaten, so he crouched and touched Grumuk’s shoulder, instead. The muttering mouth snapped instantly shut, and the cloudy old eyes peered up at him.

“D’ye have summat fer me, M’lord?” he wheedled, and Bahzell shook his head regretfully.

“Not this time, granther,” he apologized, “but I’m thinking it may be you have something for me?”

The old man’s face fell, for Bahzell knew how he hungered for the sweetmeats a child might crave and often carried them for him, but he only shook his head. His life was filled with disappointments, and he dragged out a huge, roughly woven sack. Bahzell’s eyes lit as he unwrapped the dirty clothing Tala had wadded around the arbalest and ran his fingers almost lovingly over the wooden stock and steel bow stave, and Grumuk cackled again.

“Did good fer ye, did I, M’lord?”

“Aye, old friend, that you have.” Bahzell touched his shoulder again, then straightened and slung the arbalest over his right shoulder. The old man grinned up at him, and Bahzell smiled back.

“You’d best bide here a mite,” he said. He turned to squint at the westering sun, then pointed at the broken stump of a drunken tower whose foundations, never too firm to begin with, were sinking slowly into the muck and sewage of the swampy river. “Sit yourself where you are, Grumuk, until the sun touches that tower yonder. Do you mind that? Will you do that for me?”

“Oh, aye, M’lord. That’s not so hard. Just sit here with m’ thoughts till th’ tower eats th’ sun. I c’n do that, M’lord,” Grumuk assured him.

“Good, Grumuk. Good.” Bahzell patted the old man’s shoulder once more, then turned and jogged away into the shadows of the abandoned keep’s walls.

***

The raucous stench of Navahk’s streets was reassuringly normal as Bahzell strode down them. Screaming packs of naked children dashed in and out about their elders’ feet, absorbed in gods knew what games or wrestling for choice bits of refuse amid the garbage, and he drew up a time or two to let them pass. He kept a close hand on his belt pouch when he did, other hand ready to clout an ear hard enough to ring for a week, but he no more blamed them for their thieving ways than he blamed the half-starved street beggars or whores who importuned him. Whores, especially, were rare in Hurgrum-or most other hradani lands-but too many women had lost their men in Navahk.

He made himself move casually, painfully aware of the armor he wore and the rucksack and arbalest on his back. Afternoon was dying into evening, thickening the crowd as the farmers who worked the plots beyond the wall streamed back to their hovels, but most he passed cringed out of his way. They were accustomed to yielding to their betters-all the more so when that better towered a foot and more above the tallest of them with five feet of blade on his back-and Bahzell was glad of it, yet his spine was taut as he waited for the first shout of challenge. Whether it came to fight or flight, he had a better chance here than he would have had in the palace . . . but not by much.

Yet no one shouted, and he was almost to the east gate when he spied two women moving slowly against the tide ahead of him. Farmah leaned heavily on the shorter, stouter housekeeper, and a tiny pocket of open space moved about them. A few people looked at them and then glanced uncomfortably away, and one or two almost reached out to help, but the combination of Farmah’s battered face and the palace livery both of them wore warned off even the hardiest.

Bahzell swallowed yet another curse on Churnazh and all his get as he watched men shrink away from the women and compared it to what would have happened in Hurgrum. But this wasn’t Hurgrum. It was Navahk, and he dared not overtake them to offer his own aid, either.

It was hard, slowing his pace to the best one Farmah could manage while every nerve screamed that the pursuit had to be starting soon, yet he had no choice. He followed them down the narrow street, dodging as someone emptied a chamber pot out the second-floor window of one of Navahk’s wretched inns. A pair of less nimble farmhands snarled curses up at the unglazed windows as the filth spattered them, but such misadventures were too common for comment here, and their curses faded when they suddenly realized they were standing in Bahzell’s path. They paled and backed away quickly, and he shouldered past them as Tala and Farmah turned the last bend towards East Gate.

He hurried a little now, and his heart rose as he saw the under-captain in charge of the gate detachment glance at the women. He’d thought he remembered the gate schedule, and he was right. Under-Captain Yurgazh would never have met Prince Bahnak’s standards, but at least his armor was well kept and reasonably clean. He looked almost dapper compared to the men he commanded, and he was one of the very few members of Churnazh’s Guard to emerge from the war against Hurgrum with something like glory. He’d been little more than a common freesword, but he’d fought with courage, and his example had turned the men about him into one of the handfuls that held together as the pikes closed in. It took uncommon strength to hold hradani during a retreat-and even more to restrain them from final, berserk charges while they fell back-which was why Yurgazh had risen to his present rank when Churnazh recruited his depleted Guard back up to strength.

Perhaps it was because he had nothing to be ashamed of that Yurgazh was willing to show respect for the warriors who’d vanquished him. Or perhaps he simply hadn’t been long enough in Navahk’s service to sink to its level. It might even be that he’d come to know more about the prince he served and chose to vent some of his disgust in his own, private way. But whatever his reasons, he’d always treated Bahzell as the noble he was, and Bahzell was betting heavily on the core of decency he suspected Yurgazh still harbored.

He paused at the corner, watching with narrowed eyes as Yurgazh started towards the women. Then the under-captain stopped, and Bahzell tensed as his head rose and one hand slipped to his sword hilt. Tala’s tale of seeking a healer for Farmah would never pass muster here, for there were no healers in the hovels against the outer face of the wall. Nor were palace servants allowed to leave the city without a permit, especially so late in the day, and two women alone, one of them obviously beaten and both with the shoulder knot of the prince’s personal service, could mean only one thing to an alert sentry.

Bahzell saw the understanding in Yurgazh’s face, even at this distance, and his jaw clenched as the under-captain suddenly looked up. His eyes locked on Bahzell like a lodestone on steel, and Bahzell held his breath.

But then Yurgazh released his sword. He turned his back on the women and engaged the other two gate guards in a discussion that seemed to require a great many pointed gestures at ill-kept equipment, and both of them were far too busy placating his ire to even notice the two women who stole past them.

Bahzell made his jaw unclench, yet he allowed himself no relaxation. He still had to get past, and that was a much chancier proposition when none of Churnazh’s personal guardsmen accompanied him.

He strode up to the gate, and this time Yurgazh stepped out into the gateway. He waved one of his men forward-one who looked even less gifted with intelligence than most-and Bahzell let his bandaged hand rest lightly on his belt, inches from his dagger, as the under-captain nodded respectfully to him.

“You’re out late, M’lord.” Yurgazh had better grammar than most of Churnazh’s men, and his tone was neutral. Bahzell flicked his ears in silent agreement, and a ghost of a smile flickered in Yurgazh’s eyes as they lingered briefly on the Horse Stealer’s rucksack and arbalest. “Bound for a hunting party, M’lord?” he asked politely.

“Aye,” Bahzell said, and it was true enough, he reflected-or would be once Harnak was found.

“I see.” Yurgazh rubbed his upper lip, then shrugged. “I hate to mention this, M’lord, but you really should be accompanied by your bodyguards.”

“Aye,” Bahzell repeated, and something very like the Rage but lighter, more like the crackle of silk rubbed on amber, made him want to grin. “Well, Captain, I’m thinking the guards will be along soon enough.”

“Oh? Then His Highness knows you’re going on ahead?”

“Aye,” Bahzell said yet again, then corrected himself with scrupulous accuracy. “Or that’s to say he will know as soon as Prince Harnak thinks to tell him.”

Yurgazh’s eyes widened, then flicked towards the gate through which the women had vanished before they darted back to Bahzell and the bloody cloth knotted about his knuckles. A startled look that mingled alarm and respect in almost equal measure had replaced their laughter-and then the under-captain shrugged and glanced at the dull-faced guardsman beside him.

“Well, if Prince Harnak knows you’re going, M’lord, I don’t see how it’s our business to interfere.” His underling didn’t-quite-nod in relief, but his fervent desire not to meddle in his prince’s business was plain, and Bahzell suddenly realized why Yurgazh had brought him along. He was a witness the under-captain had done his duty by questioning Bahzell . . . and that nothing Bahzell had said or done had been suspicious enough to warrant holding him.

“In that case, I’d best be going, Captain,” he said, and Yurgazh nodded and stepped back to clear the gate for him.

“Aye, so you had. And-” something in the other’s suddenly softer tone brought Bahzell’s eyes back to his “-good fortune in the hunt, M’lord.”

Chapter Three

Tala stumbled again, and this time she lost her balance completely in the darkness. She fell hard, with a muffled cry of pain, and Bahzell bit back any word of encouragement as she struggled back up. Part of him wanted to rant at her for her clumsiness; most of him was astonished by how well she’d borne up . . . and sensed her bitter shame that she’d done no better. That was foolish of her, of course; no city woman of her age could hope to match the pace of a trained warrior of half her years, which was the very reason he’d hesitated to bring her along in the first place.

But foolish or no, he respected her determination and courage . . . which, in a strange way, was what forbade soothing words they both would know as lies. Bahzell had been trained in a school whose demands were brutally simple and in which weakness was the unforgivable sin. It wasn’t enough that a man had “done his best” when defeat meant death, not just for himself but for his fellows. If his “best” wasn’t enough, he must be driven-goaded-until it was; if he couldn’t be driven, then he must be discarded. Yet this woman had somehow clung to courage and self-respect despite all her world had done to her, and she knew without telling that she was slowing him. He might not fully understand his compassion, if such it was, for her, but he knew nothing he said or did could drive her to greater efforts, and he refused to shame her with platitudes that treated her as less than she was.

None of which changed her desperate need for rest. He inhaled deeply, deliberately letting her hear the weariness in the sound, and squatted to slide Farmah from his shoulder. He eased her limp body to the ground in the shadowy underbrush, and Tala sagged back on her haunches, gasping for breath and huddling in her cloak as the night’s chill probed at her sweat-soaked garments.

He let her see him wipe matching sweat from his own forehead, and the gesture was less for her sake than he would have liked. Two years penned within hostile walls had taken their toll.

He shook himself and looked around. Hradani night vision was more acute than that of most of the Races of Man, and Bahzell’s was superior to the average hradani’s. It had better be, at any rate. The path they’d forced through the undergrowth seemed dismayingly obvious as he peered back down the slope, but perhaps it would be less so to mounted men pursuing them along the road they’d left a league back.

He hoped it would, anyway, and cradled his arbalest across his thighs while he glared into the darkness and made himself think.

A few he’d known would be praying to every god they could think of by now, but most hradani had little use for gods and prayers, and a distressing number of those who did gave their devotion to one or another of the dark gods. Theirs was a harsh world, and a god who rewarded his (or her) worshipers with immediate, tangible power, whatever its price, was at least something they could understand. Of all the gods, Krashnark undoubtedly boasted the largest following among hradani. Lord of devils and ambitious war he might be, but whatever the Black Swordsman’s other failings, he was reputed to be a god of his word, not an innate treacher like his brothers Sharna and Fiendark, and far less . . . hungry than his sister Krahana.

For the most part, however, the only use hradani had for deities was the laying of curses. Bahzell himself had no use at all for the dark gods, and precious little more for those of the light; black or white, no god had done his people any favors he knew of in the last ten or twelve centuries, and he saw little point hoping one of them might suddenly change his mind for Bahzell Bahnakson’s sake. Demons, now. A good, nasty demon, suitably propitiated, could have been a help-assuming he’d had either the means or the stomach for bargaining with one of them.

He hid the motion of his arm from Tala with his body as he touched Farmah’s throat. Her pulse throbbed against his fingers, more racing than he would have liked yet steadier than he’d feared. She’d done her dogged best, but she’d collapsed less than a mile from East Gate. She’d begged them to leave her and save themselves, but Bahzell had only snorted and given his rucksack to Tala so he could sling the girl over his shoulder, and her protests had died as exhaustion and pain dragged her under.

He sighed and withdrew his fingers from her throat to stroke her hair. It wasn’t something he would have done if anyone could see-pity was dangerous; once revealed, it could never be hidden again, and enemies would be quick to use it against you-but his heart twisted within him as he looked down upon her. So young, he thought. So young to have suffered so much, packed so much loss into so few years. Bahzell was thirty-eight, barely into the start of young manhood for a hradani, but Farmah was less than half his age, and he bared his teeth in a snarl of self-disgust at having let consideration of political consequences stay his hand while Harnak lay helpless at his feet.

A soft sound drifted through the night, and he froze, foxlike ears swiveling to track the noise. It came again, and his spine relaxed as he realized it came from the far side of the small hill on which they crouched, not from behind them.

He reached out and grasped Tala’s shoulder. The housekeeper jumped, but he’d found time to instruct her in at least the rudiments of how to conduct herself in the field, and she swallowed her gasp of surprise and kept her mouth shut as he drew her towards him.

“Horses,” he breathed in her ear. Her muscles snapped tighter, and he gave a quick headshake. “Not following us; ahead, over the hill.”

Tala’s ear twitched, and she inhaled sharply, but her relief was far from total. He approved of her taut wariness, yet if those horse sounds meant what they might-

“Wait here,” he whispered, and slipped away into the darkness.

The housekeeper watched him vanish, astonished afresh at how silently so huge a warrior moved. He was thrice her size and more, yet he’d seemed like a ghost as darkness fell, moving, despite his armor and the burden of Farmah’s limp weight, with a quiet Tala couldn’t even hope to match. Now he disappeared into the underbrush with no more than the soft whisper of a single branch against his scale shirt, and the night closed in about her.

Wind sighed-the coldest, loneliest sound she’d ever heard-and she shivered again, trying to imagine a warrior of Navahk who wouldn’t simply keep going into the dark. No one could have blamed Lord Bahzell for abandoning them. He’d already risked far more for two women of his clan’s enemies than he ever should have, yet she could no more imagine his leaving them behind than she could believe a Navahkan would have returned for them.

She settled Farmah’s head in her lap, spreading her cloak to share her own warmth with that cruelly battered body, and her eyes were cold with a hate that more than matched her fear. She was glad she’d helped Lord Bahzell, whatever came of it. He was different, like Fraidahn, her long dead husband had been-like her son had been before Churnazh took him off to war and left him there, only stronger. And kinder. Gentler. It was hard for a mother to admit that, yet it was true, however he sought to hide it. But perhaps if some god had let Durgaz grow up free of Navahk . . .

She closed her eyes, hugging the dead memories of the only people she’d ever made the mistake of allowing herself to love, and moistened a cloth from Lord Bahzell’s water bottle to wipe Farmah’s unconscious brow.

***

The underbrush slowed Bahzell, but there’d been times on the Wind Plain when he would have given an arm-well, two or three fingers from his off hand-for cover to match it. He reached the crest of the hill and raised his head above the bushes, and his eyes glittered as he saw what he’d hoped for.

No wonder there was so much underbrush and the few trees were all second growth. The moon was full enough, even without the odd chink of light streaming through the shutters of the three cottages which were still occupied, for him to tell the farm below him had known better days. Half the outbuildings were abandoned, judging by their caved-in thatch, but the overgrown hills about the farm had almost certainly been logged off in those better, pre-Churnazh days. They’d gone back to wilderness for lack of hands to work the land, yet someone still fought to save his steading from total ruin. The garden plots closer in to the buildings looked well maintained in the moonlight, clusters of sheep and goats dotted the pastures . . . and a paddock held a dozen horses.

Bahzell chuckled and let his eyes sweep patiently back and forth. Farms usually had dogs, and there was probably someone on watch, as well. Now where would he have put a sentry . . . ?

His ears rose in respect as he caught the faint glint of moonlight on steel. It wasn’t on the ground after all, for a sort of eaves-high walkway had been erected around the roof of the tallest barn. It gave a commanding view over the approaches to the farm, and there wasn’t a single watchman; there were two of them, each marching half the walkway’s circuit.

He settled down on his belly, resting his chin on the hands clasped under his jaw, and pondered. Those would be no fine saddle beasts down there, but any horse was better than the pace Tala could manage afoot. Yet how to lay hands on them? What would have been child’s play with two or three other Horse Stealers to help became far more problematical on his own-especially when he had no wish to hurt any of those farmers if he could avoid it. Anyone who could maintain even this much prosperity so close to Churnazh deserved better than to be killed by someone running from that same Churnazh, so-

He pursed his lips with a sour snort as he watched the sentries. It was hardly the proper way for a Horse Stealer to go about things, but he was in a hurry. Besides, if he was lucky, no one would ever learn of his lapse.

He rose quietly and headed back to tell Tala what he intended.

***

There were dogs. A chorus of Rūmbling snarls warned him as they came out of the dark, and he reached back to his sword hilt, ready to draw at need. But there was no need. No doubt there would have been if he’d come in across the fields, which was why he’d been careful to stick to the center of the track leading to the farm, and his open approach held them to a snarling challenge while the pack leader set up a howl to summon their master.

Bahzell stopped where he was, resting his palm on his pommel, and admired the dogs’ training while he waited. It wasn’t a long wait. Half a dozen sturdy hradani, all shorter than he, but well muscled from hard work and better food than most Navahkan city-dwellers ever saw, tumbled out of cottage doors. Bare steel gleamed in moonlight as they spread out about him, and Bahzell couldn’t fault their cautious hostility.

“Who be ye?” a strident voice challenged. “And what d’ye want, a-botherin’ decent folk in the middle o’ the night?!”

“It’s sorry I am to disturb you,” Bahzell replied calmly. “I’m but a traveler in need of your help.”

“Hey? What’s that? In need o’ help?” The voice barked a laugh. “You, wi’ a great, whackin’ sword at yer side an’ a shirt o’ mail on yer back, need our help?” The spokesman laughed again. “Ye’ve a wit fer a dirty, sneakin’ thief-I’ll say that fer ye!”

“It’s no thief I am tonight,” Bahzell said in that same mild voice, deliberately emphasizing his Hurgrum accent, “though I’ve naught against splitting a few skulls if you’re caring to call me so again.”

The spokesman rocked back on his heels, lowering his spear to peer at the intruder, and Bahzell gave back look for look.

“Yer not from around here, are ye?” the farmer said slowly, and it was Bahzell’s turn to snort a laugh.

“You might be saying that.”

“So I might.” The farmer cocked his head up at Bahzell’s towering inches. “In fact, ye’ve the look o’ one o’ them Horse Stealers. Be ye so?”

“That I am. Bahzell, son of Bahnak, Prince of Hurgrum.”

“Arrr! Tell us another ’un!” someone hooted, but the spokesman shook his head and held up a hand.

“Now, lads, let’s not be hasty. I’ve heard summat o’ this Bahzell. ’Tis said he’s tall as a hill, like all them Horse Stealers, an’ danged if this ’un isn’t.”

Bahzell folded his arms and looked down on them. The tallest was barely five or six inches over six feet, and he saw ears moving and eyes widening in surprise as they peered back up at him.

“But that Bahzell, he’s a hostage up t’ Navahk an’ all,” a voice objected.

“Aye, that’s true,” someone else agreed. “Leastways, he’s s’posed t’ be.” A note of avarice crept into his voice. “Reckon they’d pay t’ get ’im back agin, Turl?”

“Not s’much as tryin’ t’ lay him by the heels ’ud cost us , Wulgaz,” the spokesman said dryly, “an’ I’ve few enough t’ work the land wi’out his spilling yer guts in the dirt.”

Bahzell’s teeth gleamed in a moonlit smile, and the one called Wulgaz shuffled quickly back beside his fellows.

“Mind ye, though, stranger,” Turl said sharply, “there’s enough o’ us t’ spill yer guts, too, if it comes t’ that!”

“I’m thinking the same thing,” Bahzell agreed equably, “and if it’s all the same to you, I’d sooner I kept mine and you kept yours, friend.”

“Would you, now?” Turl gave a gravel-voiced chuckle and grounded the butt of his spear so he could lean on it. “Well then, Lord Bahzell-if that’s truly who ye be-what brings ye here?”

“Well, as to that, I’d half a mind to be stealing some of your horses, till I spied those lads of yours up on the roof.”

“Did ye, though?” Turl cocked his head the other way. “ ’Tis a strange way ye have o’ provin’ ye mean no harm!”

“Why? Because I’d a mind to take what I need? Or because I decided to buy, instead?”

“Buy?” Turl snapped upright. “D’ye mean t’ say buy , M’lord? Cash money?”

“Aye. Mind you, I’m thinking it would have been more fun to steal them,” Bahzell admitted, “but it’s a bit of a hurry I’m in.”

Turl gaped at him, then laughed out loud. “Well, M’lord, if its fun ye want, just go back down th’ track and me an’ the lads can step back inside an’ let ye try agin. Course, the dogs’ll be on ye quick as spit, but if that’s yer notion o’ fun-” He shrugged, and Bahzell joined him in his laughter.

“No, thank you kindly. It may be I’ll take you up on that another day, but I’ve scant time for such tonight. So if you’re minded to sell, I’ll buy three of them from you, and tack to go with them, if you have it.”

“Yer serious, ain’t ye?” Turl said slowly, rubbing his chin. “ ’Twouldn’t be ye’ve need t’ be elsewhere, would it, M’lord?”

“It would, friend, and the sooner the better.”

“Um.” Turl looked at his fellows for a long, silent moment, then back at Bahzell. “Horses are hard come by in these parts, M’lord,” he said bluntly, “an’ harder t’ replace. ’Specially when partin’ wi’ ’em seems like t’ bring th’ Black Prince an’ his scum down on ye.”

“Aye, I’ve little doubt of that,” Bahzell agreed, “and I’d not be wishing that on anyone, but I’ve a thought on that.”

“Do ye?” Turl squatted on his heels, waving the others to do the same when Bahzell followed suit. “Tell me, then, M’lord. How does an honest farmer sell his horses t’ the likes o’ you wi’out Black Churnazh stretchin’ his neck fer his troubles?”

“As to that, friend Turl, I’m thinking there’s always a way, when a man’s looking hard enough.” Bahzell shook his purse, letting them hear the jingle of coins, and cocked his head. “Now, as for how it works, why-”

***

Tala looked up nervously as hooves thudded on the dirt track. She parted the screen of branches, peering out of the clump of brush Bahzell had hidden her and Farmah in, and her ears twitched in silent relief as she recognized the huge, dark shape leading the horses.

Bahzell stopped them with a soft, soothing sound, and Tala helped Farmah to her feet. The girl had regained a little strength during Bahzell’s absence, and she clung to Tala as the housekeeper half-led and half-carried her out of the brush.

“I never thought you could do it, M’lord. Never ,” Tala breathed. “How did you ever get them to agree without-?” Her eyes cut to his sword hilt, and he chuckled.

“As to that, it wasn’t so hard a thing. Mind, that farmer’s missed his calling, for he’s one could make money selling stones to Purple Lords.” He shook his head and looked at the three unprepossessing animals behind him. “My folk wouldn’t be wasting pot space on two of these, and the third’s no courser! I’ve no mind at all to hear what old Hardak or Kulgar would be saying if they knew I’d paid for nags like these!” He shook his head again, trying to imagine the expressions of the two captains who’d led a very young Bahzell on his first raid against the vast Sothōii herds if they could see him now. Imagination failed, and he was just as glad it did.

“But how did you talk them into it?” Tala pressed, and he shrugged.

“I’d a heavy purse, and it’s a lighter one now. They took every Navahkan coin I had, and the lot of us spent ten minutes breaking down paddock fences and scuffing the ground.” He shrugged again. “If any of Churnazh’s men track us back to them, why, they’ve proof enough how hard they tried to stop my stealing these miserable racks of-that’s to say, these noble beasts.” He sounded so wry Tala chuckled, despite her exhaustion and fear, and he grinned.

“There’s the spirit! Now let’s be getting Farmah in the saddle.”

Neither woman had ever ridden a horse. Tala, at least, had ridden muleback a time or two before she fell into Churnazh’s service, but Farmah had no experience at all, and she was in no fit state for lessons. She bit her lip, wide skirt bunched clumsily high, clutching at the high cantle of the saddle and trying not to flinch as the stolid horse shifted under her, and Bahzell patted her shoulder encouragingly. It wasn’t hard to reach. Even mounted, her head was little higher than his.

“Don’t be fretting, lass,” he told her. “These are war saddles,” his palm smacked leather loudly, “and you’ll not fall out.”

She nodded uncertainly as he buckled a strap around her waist, snapped it to rings on the saddle, and grinned at her.

“I’m thinking friend Turl-the son of Hirahim who parted with these nags-wasn’t always a farmer. Not with these in his barn.” He bent to adjust the stirrups to her shorter legs and went on speaking. “But however he came by them, it’s grateful I am he had them. Wounded stay with the column or die in war, lass; that’s why they’ve straps to hold a hurt man in the saddle.”

She nodded nervously, and he gave her shoulder another pat and turned to Tala. The housekeeper had split her skirts down the middle and bound the shredded halves tightly about her legs; now she scrambled up into the second saddle without assistance. Fortunately, the plow horse under it was staid enough not to shy at her clumsy, if determined, style, and Bahzell nodded in approval and showed her how to adjust the straps. She had the reins in her hands, and he managed not to wince as he rearranged her grip, then tied the lead from Farmah’s horse to the back of her saddle.

“But . . . what about you, M’lord?” Tala asked as she glanced at the third horse. It had no saddle, only a pack frame.

“Now wouldn’t it be a cruel thing to be putting the likes of me on a horse’s back?” Bahzell replied, slinging his rucksack to the frame. “I’ve yet to meet the beast that can carry me more than a league-or outpace me over the same distance, for that matter.”

“But I thought-” Tala broke off as he looked at her, then shrugged. “They do call you ‘Horse Stealers,’ M’lord,” she said apologetically.

“And so we are, but that’s for the cooking pot.”

“You eat them?!” Tala looked down at the huge animal under her, and Bahzell chuckled.

“Aye, but don’t be saying so too loudly. You’ll fret the poor beasties, and no Horse Stealer would be eating anything this bony.” Tala blinked, and Bahzell lowered his ears more seriously.

“Now pay me heed, Tala. Churnazh will be after us soon-if he’s not already-and I’m thinking there’s no way the three of us can show them our heels.” One ear flicked at Farmah, drooping in the saddle, her small store of recovered energy already spent, and Tala nodded silently.

“Well, then. When you can’t outrun them, it’s time to outthink them. That’s why I’ve gone west, not east for Hurgrum as they might expect. But when they miss us on the east road, even the likes of Churnazh will think to sweep this way, as well.”

He paused, ears cocked, until Tala nodded again.

“I’d a few words with Turl,” he went on then, “and there’s one lad as wants us caught no more than we do, not with the questions they’ll be asking when they see saddles on the horses I ‘stole’! From the way he tells it, there’s a village-Fir Hollow, he called it-two leagues northeast of here. Do you know it?”

“Fir Hollow?” Tala repeated the name and furrowed her brow, then shook her head. “I’m afraid not, M’lord,” she apologized, and Bahzell shrugged.

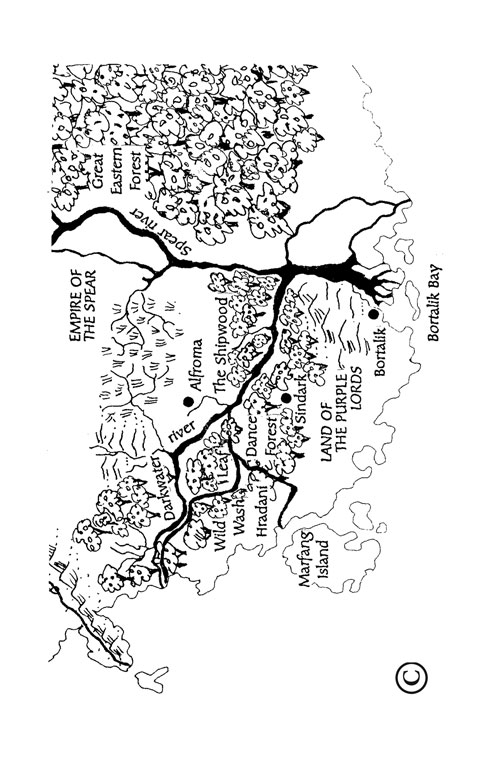

“No reason you should, but here’s what I’m thinking. The road forks there, and the right fork-the eastern one-hooks north towards Chazdark.”

“Oh!” Tala nodded sharply. “I know that town, M’lord. Fraidahn and I were there once, before-” She broke off, pushing the painful memory aside, and Bahzell squeezed her forearm.

“Good. We’ll be heading cross-country a while longer, then cut back to reach the road between Fir Hollow and Chazdark, and I’ll find a place for the two of you to lie close during the day. Tomorrow night, you’ll be back on your way to Chazdark, and I’m thinking you’ll reach it before dawn.”

“We’ll be on our way, M’lord?” Tala asked sharply. “What about you? ”

“I’ll not be with you,” he said, and she sat very straight in the saddle and stared at him. He pulled a ring off his finger, and she took it, too stunned even to argue as he dug a scrap of parchment from his pouch and passed it over, as well.

“It’s sorry I am to be leaving so much to you, Tala,” he said quietly, “but a blind man couldn’t miss the three of us together, and even ahorse, Farmah can’t move fast enough. They’ll run us down in a day at the best pace we can make if they spy us in the open, so we’ll not get Farmah to Hurgrum without showing them another hare to chase.”

“What do you mean, M’lord?” she asked tautly.

“Get off the horses when you near Chazdark. Tether them in the woods somewhere you’re certain you can be describing to someone else and leave Farmah with them. Then take this-” he touched the parchment “-to the city square, and ask for a merchant called Ludahk.” He repeated the name several times and made her repeat it back to him three times before he was satisfied. “Show him the parchment and the ring and tell him I sent you. Tell him where to be finding Farmah and the horses, and that I said he’s to take you to my father.” He held her eyes in the moonlight, face grim. “Tell him one last task pays for all-and that I’ll be looking for him if it should happen he fails in it.”

“W-Who is this Ludahk?” Tala asked in a tiny voice.

“Best know no more than you must. He’ll not be happy to see you any road; if he thinks you know more than that he’s a merchant who trades with Hurgrum-aye, and maybe does a little smuggling on the side-he might be thinking he should take his chance Churnazh can lay me by the heels and cut your throats himself.”

Tala paled and swallowed hard, and Bahzell grinned at her.

“Hush, now! Ludahk knows I’m not so easy taken as that, and he’ll not want the least chance that I might come hunting him, for he knows I won’t come alone if I do. He’ll see you safe to Hurgrum-just don’t you be looking about you at anything you shouldn’t be seeing. Understand?”

“Yes, M’lord.” He nodded and started to turn away, but she caught his shoulder, and he turned back with ears at half-cock. “I understand, M’lord, but what I don’t understand is why you don’t come with us. If this Ludahk can get us to Hurgrum, why can’t he get you there?”

“Well, now,” Bahzell said slowly, “I’m a mite bigger and harder to hide than you are.”

“That’s not the reason!” she said sharply, and he shrugged.

“Well, if you’ll have it out of me, I’ve a mind to head on west and see to it Churnazh thinks you and Farmah are with me still.”

“But . . . but they’ll catch you, M’lord!” she protested. “Come with us, instead. Please , M’lord!”

“Now that I can’t,” he said gently. “If Churnazh is minded to see it so, I’ve already broken hostage bond, and I can’t be taking that home with me unless I’m wanting to start the war all over, so there’s no sense in trying. And as long as they’re hunting west for the three of us, they’ll not be checking merchant wagons moving east, I’m thinking.”

“But they’ll catch you!” she repeated desperately.

“Ah, now. Maybe they will, and maybe they won’t,” he said with an outrageous twitch of his ears, “and the day a pack of Bloody Swords can catch a Horse Stealer with a fair start in the open, why that’s the day they’re welcome to take his ears-if they can!”

Chapter Four

Bahzell moved quickly through brush-dotted, waist-high grass while the shadows lengthened behind him. His packhorse had given up trying to hold to a pace it found comfortable, though its eyes reproached him whenever he made one of his infrequent halts.

Bahzell grinned at the thought, amused despite the nagging sensation between his shoulder blades that said someone was on his trail. Seen in daylight, the gelding was less the nag he’d told Tala; indeed, there was a faint hint of Sothōii breeding, though untrained eyes might not have noticed, and he’d kept it because it was the best of the lot. If desperation forced him to mount, it could bear him faster-and longer-than either of the others. Not that any normal horse could carry him far, at the best of times. Despite their well-earned name, nothing short of a Sothōii courser could carry an armored Horse Stealer, and trying to steal one of the sorcery-born coursers, far less mount one, was more than any hradani’s life was worth.

He paused, turning his back to the setting sun to squint back into the east, and gnawed his lip. He wanted Churnazh’s men to follow him instead of the women, but a blind man couldn’t miss the trail he’d left forging through the tall grass, and, unlike himself, the Bloody Swords were small enough to make mounted troops. Bahzell would back his own speed against anything short of Sothōii cavalry over the long haul, but a troop with enough remounts could run him down if they set their minds to it.

The thought gave added point to the itch between his shoulders, and his ears worked slowly as he studied his back trail. His stomach rumbled, but he ignored it. He’d left Tala and Farmah most of the food Turl had been able to provide, for no one had ever trained them to live off the country. He took a moment to hope they’d reached Ludahk safely, then pushed that thought aside, too. Their fate was out of his hands now, and he had his own to worry about.

He snorted at the thought, then stiffened, ears suddenly flat, as three black dots crested a hill well behind him. He strained his eyes, wishing he had a glass, but it didn’t really matter. He could count them well enough, and there was only one reason for anyone to follow directly along his trail.

He looked back into the west, and his ears rose slowly. An irregular line of willows marked the meandering course of a stream a mile or so ahead, and he nodded. If those lads back there wanted to catch him, why, it would only be common courtesy to let them.

***

The sun had vanished, but evening light lingered along a horizon of coals and dark blue ash, and Bahzell’s smile was grim as he heard approaching hooves at last.

He lay flat in the high grass with his arbalest. Few hradani were archers-their size and disposition alike were better suited to the shock of melee-but the Horse Stealers of northern Hurgrum had become something of an exception. Their raids into the Wind Plain pitted them against the matchless Sothōii cavalry’s horse archery more often than against their fellow hradani, and one of Prince Bahnak’s first priorities had been to find an answer to it.

Nothing Hurgrum had could equal the combined speed and power of the Sothōii composite bow, but the Sothōii had learned to respect Horse Stealer crossbows. A Horse Stealer could use a goatsfoot to span a crossbow, or even an arbalest, which would have demanded a windlass of any human arm. They might be slower than bowmen, but they were faster than any other crossbowmen, their quarrels had enormous shock and stopping power, and a warheaded arbalest bolt could pierce even a Wind Rider’s plate at close range.

More to the present point, those same crossbows, coupled with the pikes and halberds Bahnak’s infantry had adopted to break mounted charges, had wreaked havoc against Navahk and Prince Churnazh’s allies . . . just as Bahzell intended to do against whoever had been rash enough to overtake him.

The hooves came closer, and Bahzell rose to his knees, keeping his head below the level of the grass. It would be awkward to respan an arbalest from a prone position, even for him, but he’d chosen his position with care. His targets should be silhouetted against the still-bright western sky while he himself faded into the dimness of the eastern horizon, with time to vanish back into the grass before they even realized they were under attack. Of course, if they chose to stand, they were almost bound to spot him when he popped back up to take the second man, so there’d be no time for a third shot. But he’d take his chances against a single Bloody Sword hand-to-hand any day, and-

His thoughts broke off as the hooves stopped suddenly.

“I know you’re out there,” a tenor voice called, “but it’s getting dark, and mistakes can happen in the dark. Why don’t you come out before you shoot someone we’d both rather you didn’t?”

“Brandark?! ” Bahzell shot up out of the grass in disbelief, and the single horseman turned in his saddle.

“So there you are,” he said blandly, then shook his head and waved an arm at the line of willows two hundred yards ahead. “I’m glad I went ahead and called out! I thought you were still in front of me.”

“Fiendark’s Furies, man!” Bahzell unloaded the arbalest and released the string with a snap while he waded through the grass. “What in the names of all the gods and demons d’you think you’re doing out here?!”

“Catching up with you before any of Churnazh’s patrols do,” Brandark said dryly, and leaned from his saddle to clasp forearms as Bahzell reached him. “Not that it’s been easy, you understand. I’ve just about ridden these poor horses out.”

“Aye, well, that happens when the likes of you goes after a Horse Stealer, little man. You’ve not got the legs to catch him, any of you.” Bahzell’s tone was far lighter than his expression. “But why you should be wanting to is more than I can understand.”