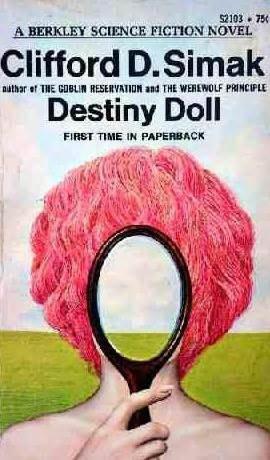

THE PLANET BECKONED THEM FROM SPACE —and closed round them like a Venus Fly Trap!

Assailed by strange perils and even stranger temptations, the little group stumbled towards its destiny—Mike Ross, the pilot, Sara Foster, the big game hunter, blind George Smith, and the odious Friar Tuck.

Before them was a legend made flesh, around them were creatures of myth and mystery, close behind them stalked Nemesis. The doll, the little wooden painted doll, was to be their salvation. Or their damnation, for each might choose, and find, his own Nirvana.

OTHER SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS

BY CLIFFORD D. SIMAK

AVAILABLE IN BERKLEY MEDALLION EDITIONS

STRANGERS IN THE UNIVERSE

(Selections)

THE WEREWOLF PRINCIPLE

THE GOBLIN RESERVATION

OUT OF THEIR MINDS

Copyright © 1971 by Clifford D. Simak

All rights reserved

Published by arrangement with the author's agent

SNB 425-02103-3

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS are published by Berkley Publishing Corporation 200 Madison Avenue New York, N.Y. 10016

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS ® TM 757,375

Printed in the United States of America

BERKLEY MEDALLION EDITION, JANUARY, 1972

ONE

The place was white and there was something aloof and puritanical and uncaring about the whiteness, as if the city stood so lofty in its thoughts that the crawling scum of life was as nothing to it.

And yet, I told myself, the trees towered over all. It had been the trees, I knew, when the ship started coming down toward the landing field, riding on the homing beam we'd caught far out in space, that had made me think we'd be landing at a village. Perhaps, I had told myself, a village not unlike that old white New England village I had seen on Earth, nestled in the valley with the laughing brook and the flame of autumn maples climbing up the hills. Watching, I had been thankful, and a bit surprised as well, to find such a place, a quiet and peaceful place, for surely any creatures that had constructed such a village would be a quiet and peaceful people, not given to the bizarre concepts and outlandish mores so often found on an alien planet.

But this was not a village. It was about as far from a village as it was possible to get. It had been the trees towering over the whiteness of it that had spelled village in my mind. But who would expect to find trees that would soar above a city, a city that rose so tall one must tilt his head to see its topmost towers?

The city rose into the air like a towering mountain range springing up, without benefit of foothills, from a level plain. It fenced in the landing field with its massive structure, like an oval of tall bleachers hemming in a playing field. From space the city had been shining white, but it no longer shone. It was white, all white, but soft satiny, having something in common with the subdued gleam of expensive china on a candle-lighted table.

The city was white and the landing field was white and the sky so faint a blue that it seemed white as well. All white except the trees that topped a city which surged up to mountain height.

My neck was getting tired from tilting my head to stare up at the city and the trees and now, when I lowered my head and looked across the field, I saw, for the first time, there were other ships upon the field. A great many other ships, I realized with a start—more ships than one would normally expect to find on even some of the larger and busier fields of the human galaxy. Ships of every size and shape and all of them were white. That had been the reason, I told myself, I'd not spotted them before. The whiteness of them served as a camouflage, blending them in with the whiteness of the field itself.

All white, I thought. The whole damn planet white. And not merely white, but a special kind of whiteness—all with that same soft-china glow. The city and the ships and the field itself all were china-white, as if they had been carved by some industrious sculptor out of one great block of stone to form a single piece of statuary.

There was no activity. There was nothing stirring. No one was coming out to meet us. The city stood up dead.

A gust of wind came from somewhere, a single isolated gust, twitching at my jacket. And I saw there was no dust. There was no dust for the wind to blow, no scraps of paper for it to roll about. I scuffed at the material which made up the landing surface and my scuffing made no marks. The material, whatever it might be, was as free of dust as if it had been swept and scrubbed less than an hour before.

Behind me I heard the scrape of boots on the ladder's rungs. It was Sara Foster coming down the ladder and she was having trouble with that silly ballistics rifle slung on a strap across one shoulder. It was swinging with the motion of her climbing and bumping on the ladder, threatening to get caught between the rungs.

I reached up and helped her down and she swung around as soon as she reached the ground to stare up at the city. Studying the classic planes of her face and mop of curling red hair, I wondered again how a woman of such beauty could have escaped all the softness of face that would have rounded out the beauty. She reached up a hand and brushed back a lock of hair that kept falling in her eyes. It had been falling in her eyes since the first moment I had met her.

"I feel like an ant," she said. "It just stands there, looking down at us. Don't you feel the eyes?"

I shook my head. I had felt no eyes.

"Any minute now," she said, "it will lift a foot and squash us."

"Where are the other two?" I asked.

"Tuck is getting the stuff together and George is listening, with that soft, silly look pasted on his face. He says that he is home."

"For the love of Christ," I said.

"You don't like George," said Sara.

"That's not it at all," I said. "I can ignore the man. It's this whole deal that gets me. It makes no sort of sense."

"But he got us here," she said.

"That is right," I said, "and I hope he likes it."

For I didn't like it. Something about the bigness and the whiteness and the quietness of it. Something about no one coming out to greet us or to question us. Something about the directional beam that had brought us to this landing field, then no one being there. And about the trees as well. No trees had the right to grow as tall and big as those that rose above the city.

A clatter broke out above us. Friar Tuck had started down the ladder and George Smith, puffing with his bulk, was backing out the port, with Tuck guiding his waving feet to help him find the rungs.

"He'll slip and break his neck," I said, not caring too much if he did.

"He hangs on real good," said Sara, "and Tuck will help him down."

Fascinated, I watched them coming down the ladder, the friar guiding the blind man's feet and helping him to find the rungs when he happened to misjudge them.

A blind man, I told myself—a blind man and a footloose, phony friar, and a female big game hunter off on a wild goose chase, hunting for a man who might have been no man at all, but just a silly legend. I must have been out of my mind, I told myself, to take on a job like this.

The two men finally reached the ground and Tuck, taking the blind man's arm, turned him around so he faced the city.

Sara had been right, I saw, about that silly smile. Smith's face was wreathed in beatitude and a look like that, planted on his flabby, vacant face, reeked of obscenity.

Sara touched the blind man's arm with gentle fingers.

"You're sure this is the place, George? You couldn't be mistaken?"

The beatitude changed to an ecstasy that was frightening to see. "There is no mistake," he babbled, his squeaky voice thickened by emotion. "My friend is here. I hear him and he makes me see. It's almost as if I could reach out and touch him."

He made a fumbling motion with a pudgy hand, as if he were reaching out to touch someone, but there was nothing there to touch. It all was in his mind.

It was insane on the face of it, insane to think that a blind man who heard voices—no, not voices, just a single voice— could lead us across thousands of light years, toward and above the galactic center, into territory through which no man and no human ship had been known to pass, to one specific planet. There had been, in past history, many people who had heard voices, but until now not too many people bad paid attention to them.

"There is a city," Sara was saying to the blind man. "A great white city and trees taller than the city, trees that go up and up for miles. Is that what you see?"

"No," said George, befuddled by what he had been told, "No, that isn't what I see. There isn't any city and there aren't any trees." He gulped. "I see," he said, "I see . . ." He groped for what he saw and finally gave up. He waved his hands and his face was creased with the effort to tell us what he saw. "I can't tell you what I see," he finally whispered. "I can't find the words for it. There aren't any words."

"There is something coming," said Friar Tuck, pointing toward the city. "I can't make it out. Just a shimmer. As if there were something moving."

I looked where the friar was pointing and I caught the shimmer. But that was all it was. There was nothing one could really see. Out there, at the base of the city wall, something seemed to be moving, an elusive flow and sparkle.

Sara was looking through her glasses and now she slipped the strap over her shoulder and handed them to me.

"What do you think, captain?"

I put the glasses to my eyes and moved them slowly until I caught the movement. At first it was no more than a moving blur, but slowly it grew in size and separated. Horses? I wondered. It didn't make much sense that there'd be horses here, but that was what they looked like. White horses running toward us—if there were horses, of course they would be white! But very funny horses and, it seemed, with very funny feet, not running the way a normal horse would run, but with a crazy gait, rocking as they ran.

As they came closer I could make out further detail. They were horses, all right. Formalized horses—pert upright ears, flaring nostrils, arched necks, manes that rose as if the wind were blowing through them, but manes that never moved. Like wild running horses some crummy artist would draw for a calendar, but keeping the set pose the artist had given them, never changing it. And their feet? Not feet, I saw. Not any feet at all, but rockers. Two pair of rockers, front and rear, with the front ones narrower so there'd be no interference as the horses ran—reaching forward with the rear pair and, as they touched the ground, rocking forward on them, with the front pair lifted and reaching out to touch the ground and rock in turn.

Shaken, I lowered the glasses and handed them to Sara.

"This," I said, "is one you won't believe."

She put the glasses up and I watched the horses coming on. There were eight of them and they all were white and one was so like the other there was no telling them apart.

Sara took down the glasses.

"Merry-go-round," she said.

"Merry-go-round?"

"Sure. Those mechanical contraptions they have at fairs and carnivals and amusement parks."

I shook my head, bewildered. "I never went to an amusement park," I told her. "Not that kind of amusement park. But when I was a kid I had a hobbyhorse."

The eight came rushing in, sliding to a halt. Once they halted, they stood rocking gently back and forth.

The foremost of them spoke to us, employing that universal space argot that man had found already in existence when he'd gone into space more than twenty centuries before, a language composed of terms and phrases and words from a hundred different tongues, forged into a bastard lingo by which many diverse creatures could converse with one another.

"We be hobbies," said the horse. "My name is Dobbin and we have come to take you in."

No part of him moved. He simply stood there, rocking gently, with his ears still perked, his carven nostrils flaring, with the nonexistent breeze blowing at his mane. I got the impression, somehow, that the words he spoke came out of his ears.

"I think they're cute," Sara cried, delighted. And that was typical; she would think that they were cute.

Dobbin paid her no attention. "We urge upon you haste," he said. "There is a mount for each of you and four to take the luggage. We have but a small amount of time."

I didn't like the way that it was going; I didn't like a thing about it. I'm afraid I snapped at him.

"We don't like being hurried," I told him. "If you have no time, we can spend the night on the ship and come in tomorrow morning."

"No! No!" the hobby protested frantically. "That is impossible. There exists great danger with the setting of the sun. You must be undercover by the time the sun is set."

"Why don't we do the way he says," suggested Tuck, pulling his robe tight around himself. "I don't like it out here. If there is no time now, we could come back and pick up the luggage later."

Said Dobbin, "We'll take the luggage now. There'll be no time in the morning."

"It seems to me," I said to Dobbin, "you're greatly pressed for time. If that's the case, why don't you simply turn around and go back where you came from. We can take care of ourselves."

"Captain Ross," said Sara Foster, firmly, "I'm not going to walk all that way if there's a chance to ride. I think you're being foolish."

"That may well be," I said, angrily, "but I don't like snotty robots ordering me around."

"We be hobbies," Dobbin said. "We not be any robots."

"You be human hobbies?"

"I do not know your meaning."

"Human beings made you. Creatures very much like us."

"I do not know," said Dobbin.

"The hell you don't," I said. I turned to Smith. "George," I said.

The blind man turned his puffy face toward me. The look of ecstasy still was pasted on it.

"What is it, captain?"

"In your talk back and forth with this friend of yours, did you ever mention hobbies?"

"Hobbies? Oh, you mean stamp collecting and . . ."

"No, I don't," I said. "I mean hobbyhorses. Did you ever mention hobbyhorses?"

"Until this moment," said the blind man, "I never heard of them."

"But you had toys when you were 'a child."

The blind man sighed. "Not the kind you are thinking of. I was born blind. I have never seen. The kind of toys other children had were not . . ."

"Captain," Sara said, angrily, "you are ridiculous. Why all this suspicion?"

"I'll tell you that," I said, just as angrily, "and it's an easy answer . . ."

"I know," she said. "I know. Suspicion, time and time again, has saved that neck of yours."

"Gracious lady," Dobbin said, "please believe there is great danger once the sun has set. I plead with you, I implore you, I urge you to come with us and most speedily at that."

"Tuck," said Sara, "get up that ladder and start getting down the stuff!" She swung belligerently toward me. "Have you objections, captain?"

"Miss Foster," I told her, "it's your ship and it's your money. You're paying for the show."

"You're laughing at me," she stormed. "You've laughed all the way. You never really believed in anything I told you. You don't believe at all—not in anything."

"I got you here," I told her, grimly, "and I'll get you back. That's the deal we made. All I ask is that you try not to make the job any harder than it has to be."

And immediately that I said it, I was sorry that I had. We were on an alien planet and very far from home and we should stick together and not start off with bickering. More than likely, I admitted to myself, she had been quite right; I might have been ridiculous. But right away, I amended that. Ridiculous on the surface, maybe, but not in principle. When you hit an alien planet, you are on your own and you have to keep your senses and your hunches sharp. I'd been on a lot of alien planets and had always managed and so, of course, had Sara, but she'd always hit them with a good-sized expeditionary force and I'd been on my own.

Tuck, at the first word from her, had gone swarming up the ladder, with his robe tucked up underneath his belt so he wouldn't trip, and now was handing down the duffle bags and the other plunder to Sara, who was halfway up the ladder, taking the stuff from him and dropping it as gently as she could at the ladder's base. There was one thing you had to say about the gal—she never shirked the work. She was al. ways in there, doing 'her fair share and perhaps a good deal more.

"All right," I said to Dobbin, "run your packhorses over here. How do you handle this?"

"I regret," said Dobbin, "that we haven't any arms. But with the situation as it is, you'll be forced to do the packing. Just heap the luggage on top the hobbies' backs and when the load is completed, metal cinches will extrude from the belly and strap the load securely."

"Ingenious," I said.

Dobbin made a little forward dip upon his rockers, in the semblance of hewing. "Always," he said, "we attempt to serve."

Four of the horses came rocking up and I began loading them. When Tuck got through with handing down the gear, Sara came and helped me. Tuck closed the port and by the time he had climbed down the ladder, we were all set to go.

The sun was touching the city skyline and hunks were being nibbled out of it by the topmost towers. It was slightly more yellow than the sun of Earth—perhaps a K-type star. The ship would know, of course; the ship would have it all. The ship did all the work that a man was supposed to do. It gobbled up the data and pulled it all apart and put it back together. It knew about this planet and about the planet's star, it knew about the atmosphere and the chemistry and all the rest of it and it would have been more than willing to give it out to anyone who asked. But I hadn't asked. I had meant to go back and get the data sheet, but I hadn't counted on getting a reverse bum's rush by a pack of hobbyhorses. Although, I told myself, it probably made, no difference, I could come back in the morning. But I couldn't bring myself to like the fact that I'd not latched onto that data sheet.

"Dobbin," I asked, "what is all this danger business? What are we supposed to be afraid of?"

"I cannot inform you," Dobbin said, "since I, myself, fail to understand, but I can assure you . . ."

"OK, let it go," I told him.

Tuck was puffing and panting, trying to boost Smith onto one of the hobbies, Sara already was on one of them, sitting straight and prim, the perfect picture of a gal on the threshold of a very great adventure, and that, of course, was all it was to her—another great adventure. Sitting there, proud, astride her mount, with that ridiculous ancient rifle slung across her shoulder, nattily attired in an adventure-going costume.

I glanced quickly about the bowl that was the landing field, rimmed in by the city, and there was nothing stirring. Shadows ran out from the city's western wall as the sun went inching down behind the buildings and some of those western buildings had turned from white to black, but there were no lights.

Where was everyone? Where were the city's residents and all those visitors who'd come down on the spaceships standing like ghostly tombstones on the field? And why were the ships all white?

"Honored sir," Dobbin said to me, "if you please, would you get into my saddle. Our time is running short."

A chill was in the air and I don't mind admitting that I felt a twinge of fright. I don't know why. Perhaps just the place itself, perhaps the feeling of being trapped on the landing field rimmed in by the city, perhaps the fact that there seemed no living thing in sight except the hobbies—if you could call them living and I suppose you could.

I reached up and lifted the strap of my laser gun off my shoulder and, grasping it in hand, swung into Dobbin's saddle.

"You need no weapon here," Dobbin said, disapprovingly. I didn't answer him. It was my own damn business.

Dobbin wheeled and we started out across the field, heading toward the city. It was a crazy kind of ride—smooth enough, no jerking, but going up and down as much, it seemed, as one was moving forward. It wasn't rocking; it was like skating on a sine wave.

The city seemed not to grow much larger, nor to gain in detail. We bad been much farther from it, I realized, than it bad appeared; the landing field was larger, too, than it had appeared. Behind me, Tuck let out a yell.

"Captain!"

I twisted in the saddle.

"The ship!" yelled Tuck. "The ship! They're doing something to it."

And they were, indeed—whoever they might be.

A long-necked mechanism stood beside the ship. It looked like a bug with a squat and massive body and a long and slender neck with a tiny head atop it. From the mouth of it sprayed out a mist directed at the ship. Where it struck the ship, the ship was turning white, just like those other tombstone ships that stood upon the, field.

I let out an angry yelp, reaching for a rein and yanking hard. But I might as well have yanked upon a rock. Dobbin kept straight on.

"Turn around," I yelled. "Go back!"

"There is no turning back, most honored sir," said Dobbin, conversationally, not even panting with his running. "There is no time. We must reach the safety of the city."

"There is time, by God," I yelled, jerking up the gun and aiming it at the ground in front of us, between Dobbin's ears.

"Shut your eyes," I yelled to the others, and pulled the trigger one notch back. Even through my eyelids, I sensed the flaring of the laser-light as it bounced back from the ground. Under me Dobbin reared and spun, almost swapping end for end, and when I opened my eyes we were heading back toward the ship.

"You'll be the death of us, crazy being," Dobbin moaned. "All of us will die."

I looked behind me and the hobbies all were following. Dobbin, it appeared, was leader and where he went they were content to follow. But farther back there was no sign of where the laser bolt had struck. Even at first notch capacity it should have made a mark; there should have been a smoking crater back there where it struck.

Sara was riding with one arm up across her eyes.

"You all right?" I asked.

"You crazy fool!" she cried.

"I yelled for you to close your eyes," I said. "There was bound to be reflection."

"You yelled, then fired," she said. "You didn't give us time."

She took her arm down and her eyes blinked at me and, hell, she was all right. Just something else to bitch about; she never missed a chance.

Ahead of us the bug that had been spraying the ship was scurrying off across the field. It must have had wheels or treads underneath it, for it was spinning along at a headlong clip, its long neck stretched out in front of it in its eagerness to get away from there.

"Please, sir," Dobbin pleaded, "we are simply wasting time. There is nothing that can be done."

"One more word out of you," I said, "and this time right between the ears."

We reached the ship and Dobbin skidded to a halt, but I didn't wait for him to stop. I hit the ground and was running toward the ship while he still was moving. Although what I intended to do I had no idea.

I reached the ship and I could see that it was covered with some stuff that looked like frosty glass and when I say covered, I mean covered—every inch of it. There was no metal showing. It looked unfunctional, like a model ship. Reduced in size, it could have passed for those little model ships sold in decorator shops to stick up on the mantle.

I put out my hand and touched it and it was slick and hard. There was no look of metal and there was no feel of metal, either. I rapped it with my gun stock and it rang like a bell, setting up a resonance that went bouncing across the field and came back as an echo from the city walls.

"What is it, captain?" Sara asked, her voice somewhat shaky. This was her ship, and there was no one who could mess around with it.

"A coating of something hard," I said. "As if it had been sealed."

"You mean we can't get into it?"

"I don't know. Maybe if we had a sledge hammer to crack it, we could peel it off."

She made a sudden motion and the rifle was off her back and the butt against her shoulder. I'll say this for her: crazy as that gun might be, she could handle it.

The sound of the shot was loud and flat and the hobbies reared in terror. But above the sound of the report itself was another sound, a wicked howling that almost screamed, the noise of a ricocheting bullet tumbling end for end, and pitched lower than the shrill howling of the slug was the booming resonance of the milk-white ship. But there was no indication of where the bullet might have struck. The whiteness of the ship still was smooth—uncracked, unblemished, unmarked. Two thousand foot-pounds of metal had slammed against it and had not made a dent.

I lifted the laser gun and Dobbin said to me, "There be no use, you foolish folk. There is nothing you can do."

I whirled on him angrily. "I thought I told you . . .' I yelled. "One more word out of you and right between the eyes."

"Violence," Dobbin told me, perkily, "will get you nowhere. But staying here, once the sun has set, spells very rapid death."

"But the ship!" I shouted.

"The ship is sealed," said Dobbin, "like all the others. Better sealed with you outside of it than with you still inside."

And although I would not have admitted it, I knew that he was right in saying there was nothing we could do. For I recalled that the field had been unmarked by the laser beam and undoubtedly all this whiteness was the same—the field, the ships, the city, all coated, more than likely, with some substance so tightly bonded in its atomic structure that it was indestructible.

"I sorrow greatly for you," said Dobbin, with no sorrow in his voice. "I know the shock of you. But once on this planet, no one ever leaves. Although there is no need of also dying, I plead with you compassionately to get into the saddle and let us head for safety."

I looked up at Sara and she nodded quietly. She had figured it, I knew, about the way I had, although in my case most unwillingly. There was no use in staying out here. The ship was sealed, whatever that might mean or for whatever purpose, and when morning came we could come back to see what we could do. From the moment we had met him, Dobbin had been insistent about the danger. There might be danger or there might be none—there was no way, certainly, that we could determine if there were or weren't. The only sensible thing, at the moment, was to go along with him.

I swung swiftly to the saddle and even before I found seat, Dobbin had whirled about, running even as he led.

"We have lost most valued time," he told me. "We will try with valiance to make it up. We yet may reach the city."

A good part of the landing field lay in shadow now and only the sky was bright. A faint, smokelike dusk was filtering through the city.

Once on this planet, Dobbin had said, no one ever leaves. But these were his words alone, and nothing else. Perhaps there was a real intent to keep us here, which would explain the sealing of the ship, but there would be ways, I told myself, that could be tried to get off the planet when the time to go should come. There were always ways.

The city was looming up as we drew closer, and now the buildings began to assume their separate shapes. Up till now they had been a simple mass that had the appearance of a solid cliff thrusting up from the flatness of the field. They had seemed tall from out in the center of the field; now they reared into the sky so far that, this close, it was impossible to follow with the eye up to their tops.

The city still stayed dead. There were no lights in any of the windows—if, indeed, the buildings did have windows. There was no sign of movement at the city's base. There were no outlying buildings; the field ran up to the base of the buildings and the buildings then jutted straight into the sky.

The hobbies thundered cityward, their rockers pounding out a ringing clangor as they humped along like a herd of horses galloping wildly before a scudding storm front. Once you got the hang of riding them, it wasn't bad at all. You just went sort of loose and let your body follow that undulating sine wave.

The city walls loomed directly in front of us, great slabs of masonry that went up and up, and now I saw that there were streets, or at least what I took for streets, narrow slits of empty blackness that looked like fractures in a monstrous cliff.

The hobbies plunged into one of the slits of emptiness and darkness closed upon us. There was no light here; except when the sun stood straight overhead, there never would be light. The walls seemed to rise all about us, the slit that was a street narrowing down to a vanishing point so that the walls seemed on every hand.

Ahead of us one building stood a little farther back, widening the street, and from the level of the street a wide ramp ran up to massive doors. The hobbies turned and flung themselves at the ramp and went humping up it and through one of the gaping doors.

We burst into a room where there was a little light and the light, I saw, came from great rectangular blocks set into the wall that faced us.

The hobbies rocked swiftly toward one of the blocks and came to a halt before it. To one side I saw a gnome, or what appeared to be a gnome, a small, humpbacked, faintly humanoid creature that spun a dial set into the wall beside the slab of glowing stone.

"Captain, look!" cried Sara.

There was no need for her to cry out to me—and I had seen it almost as soon as she had. Upon the glowing stone appeared a scene—a faint and shadowed scene, as if it might be a place at the bottom of a clear and crystal sea, its colors subdued by the depth of water, its outlines shifting with the little wind ripples that ran on the water's surface.

A raw and bleeding landscape, with red lands stretching to a mauve, storm-torn horizon, broken by crimson buttes, and in the foreground a clump of savage yellow flowers. But even as I tried to grasp all this, to relate it to the kind of world it might have been, it changed, and in its place was a jungle world, drowned in the green and purple of overwhelming vegetation, spotted by the flecks of screaming color that I knew were tropic flowers, and back of it all a sense of lurking bestiality that made my hide crawl even as I looked at it.

Then it, too, was gone—a glimpse and it was gone—and in its place was a yellow desert lighted by a moon and by a flare of stars that turned the sky to silver, with the lips of the marching sand dunes catching and fracturing the moon and starlight so that the dunes appeared to be foaming waves of water charging in upon the land.

The desert did not fade as the other places had. It came in a rush upon us and exploded in my face.

Beneath me I felt the violent plunging of a bucking Dobbin and made a frantic grab at the cantle of the saddle which seemed to have no cantle and then felt myself pitched forward and turning in the air.

I struck on one shoulder and skidded in the sand and finally came to rest, the breath knocked out of me. I struggled up, cursing—or trying to curse and failing, because I had no breath to curse with—and once on my feet, saw that we were alone in that land we had seen upon the glowing block.

Sara sprawled to one side of me and not far off Tuck was struggling to his feet, hampered by the cassock that had become entangled about his legs, and a little beyond Tuck, George was crawling on his hands and knees, whimpering like a pup that had been booted out of doors into a friendless. frigid night.

All about us lay the desert, desiccated, without a shred of vegetation, flooded by the great white moon and the thousand glowing stars, all shining like lamps in a cloudless sky.

"He's gone!" George was whimpering as he crawled about. "I can't hear him anymore. I have lost my friend."

And that was not all that was lost. The city was lost and the planet on which the city stood. We were in another place. This was one trip, I told myself, that I never should have made. I had known it all along. I'd not believed in it, even from the start. And to make a go of it, you had to believe in everything you did. You had to have a reason for everything you did.

Although, I recalled, I had really no choice.

I had been committed from the moment I had seen that beauty of a spaceship standing on the field of Earth.

TWO

I had come sneaking back to Earth. Not back really, for I never had been there to start with. But Earth was where my money was and Earth was sanctuary and out in space I was fair game to anyone who found me. Not that what I had done had been actually so bad, nor was I to blame entirely, but there were a lot of people who had lost their shirts on it and, they were out to get me and eventually would get me if I failed to reach Earth's sanctuary.

The ship that I was driving was a poor excuse—a fugitive from a junkyard (and that was exactly what it was), patched up and stuck together with binder twine and bailing wire, but I didn't need it long. All I wanted of it was to get me to Earth. Once I stepped out of it, it could fall into a heap for all it mattered to me. Once I got to Earth, I'd be staying there.

I knew that Earth Patrol would be on watch for me—not that Earth cared; so far as Earth was concerned, the more the merrier. Rather a patrol to keep undesirable characters like myself from fleeing back to Earth.

So I came into the solar system with the Sun between myself and Earth and I hoped that my slide rule hadn't slipped a notch and that I had it figured right. I piled on all the normal-space speed I could nurse out of the heap and the Sun's gravity helped considerably and when I passed the Sun that ship was traveling like a hell-singed bat. There was an anxious hour when it seemed I might have sliced it just a bit too close. But the radiation screens held and I lost only half my speed and there was Earth ahead.

With all engines turned off and every circuit cut, I coasted on past Venus, no more than five million miles off to my left, and headed in for Earth.

The patrol didn't spot me and it was sheer luck, of course, but there wasn't much to spot. I had no energy output and all the electronics were doused and all they could have picked up was a mass of metal and fairly small, at that. And I came in, too, with the Sun behind me, and the solar radiations, no matter how good the equipment you may have, help louse up reception.

It was insane to try it, of course, and there were a dozen very nasty ways in which I could have failed, but on many a planet-hunting venture I had taken chances that were no less insane. The thing was that I made it.

There is just one spaceport on Earth. They don't need any more. The traffic isn't heavy. There are few people left on Earth; they all are out in space. The ones who are left are the hopeless sentimentalists who think there is status attached to living on the planet where the human race arose. They, and the ones like myself, are the only residents. The sentimentalists, I had heard, were a fairly snooty crowd of self-styled aristocrats, but that didn't bother me. I wasn't planning on having too much to do with them. Occasionally excursion ships dropped in with a load of pilgrims, back to visit the cradle of the race, and a few freighters bringing in assorted cargo, but that was all there was.

I brought in the ship and set it down and walked away from it, carrying my two bags, the only possessions I had been able to get away with before the vultures had come flocking in. The ship didn't fall into a heap; it just stood there, its slab-sided self, the sorriest-looking vessel you ever clapped your eyes on.

Just two berths away from it stood this beauty of a ship. It gleamed with smart efficiency, slim and sleek, a space yacht that seemed straining toward the sky, impatient at its leash.

There was no way of knowing, of course, just by looking at it, what it had inside, but there is something about a ship that one simply cannot miss. Just looking at this one, there was no doubt that no money had been spared to make it the best that could be built. Standing there and looking at it, I found my hands itching to get hold of it.

I suppose they itched the worse because I knew I'd never go into space again. I was all washed up. I'd spend the rest of my life on Earth the best way that I could. If I ever left it, I'd be gobbled up.

I walked off the field and went through customs—if you could call it customs. They just went through the motions. They had nothing against me or anyone; they weren't sore at me, or anyone. That, it seemed to me, was the nicest thing one could say of Earth.

I went to an inn nearby and once I'd settled in, went down to the bar.

I was on my third or fourth when a robot flunky came into the bar and zeroed in on me.

"You are Captain Ross?"

I wondered, with a flare of panic, just what trouble I was in for. There wasn't a soul on Earth who knew me or knew that I was coming. The only contacts I had made had been with the customs people and the room clerk at the inn.

"I have a note for you," said the robot, handing it to me. The envelope was sealed and it had no marks upon it.

I opened it and took out the card. It read:

Captain Michael Ross,

Hilton Inn

If Captain Ross will be my dinner guest tonight, I would be much obliged. My car will be waiting at the entrance of the inn at eight o'clock. And, captain, may I be among the first to welcome you to Earth.

Sara Foster

I sat there staring at it and the bottle robot came sliding down the bar. He picked up the empty glass. "Another one?" be asked.

"Another one," I said.

Just who was Sara Foster, and how had she known, an hour after my arrival, that I was on Earth?

I could ask around, of course, but there seemed no one to ask, and for some reason I could not figure out why I felt disinclined to do so.

It could be a trap. There were people, I well knew, who hated me enough to have a try at smuggling me off the Earth. They would know by now, of course, that I had obtained a ship, but few who would believe that such a ship would carry me to Earth. And there could be none of them who could even guess I'd already reached the Earth.

I sat there, drinking, trying to get it straight in mind, and I finally decided I would take a chance.

Sara Foster lived in a huge house set atop a hill, surrounded by acres of wilderness that in turn surrounded more acres of landscaped lawns and walks, and in the center of all of this sat the huge house, built of sun-warmed bricks, with a wide portico that ran the length of the house, and with many chimneys thrusting from its roof.

I had expected to be met at the door by a robot, but Sara Foster was there, herself, to greet me. She was wearing a green dinner dress that swept the floor and served to set off, in violent contrast, the flame of her tumbled hair, with the one errant lock forever hanging in her eyes.

"Captain Ross," she said, giving me her hand, "how nice of you to come. And on such short notice, too. I'm afraid it was impetuous of me, but I did so want to see you."

The hall in which we stood was high and cool, paneled with white-painted wood and the floor of wood so polished that it shone, with a massive chandelier of crystal hanging from the ceiling. The place breached wealth and a certain spirit of Earth-rooted gentility and it all was very pleasant.

"The others are in the library," she said. "Let us go and join them."

She linked her arm through mine and led me down the hail until we came to a door that led into a room that was a far cry from the hall which I had entered. It might have been a library—there were some shelves with books—but it looked more like a trophy room. Mounted heads hung from every wall, a glass-enclosed gun rack ran across one end, and the floor was covered with fur rugs, some with the heads attached, the bared fangs forever snarling.

Two men were sitting in chairs next to the mammoth fireplace and as we entered one of them got up. He was tall and cadaverous, his face long and lean and dark, not so much darkened, I thought as I looked at him, by the outdoors and the sun as by the thoughts within his skull. He wore a dark brown cassock loosely belted at the waist by a string of beads, and his feet, I saw, were encased in sturdy sandals.

"Captain Ross," said Sara Foster, "May I present Friar Tuck."

He held out a bony hand. "My legal name," he said "is Hubert Jackson, but I prefer Friar Tuck. In the course of my wanderings, captain, I have heard many things of you."

I looked hard at him. "You have done much wandering?" For I had seen his like before and had liked none of what I saw.

He bent his bony head. "Far enough," he said, "and always in the search of truth?'

"Truth," I said, "at times is very hard to come by."

"And captain," Sara said, quickly, "this is George Smith." The second man by this time had fumbled to his feet and was holding out a flabby hand in my direction. He was a tubby little man with a grubby look about him and his eyes were a milky white.

"As you can see by now," said Smith, "I am quite blind. You'll excuse me for not rising when you first came in the room."

It was embarrassing. There was no occasion for the man to so thrust his blindness on us.

I shook his hand and it was as flabby as it looked, as nearly limp as a living hand can be. Immediately he fumbled his way back into the chair again.

"Perhaps this chair," Sara said to me. "There'll be drinks immediately. I know what the others want, but . . ."

"If you have some Scotch," I said.

I sat down in the chair she had indicated and she took another and there were the four of us, huddled in a group before that looming fireplace and surrounded by the heads of creatures from a dozen different planets.

She saw me looking at them. "I forgot," she said. "You'll excuse me, please. You had never heard of me—until you got my note, I mean."

"I am sorry, madam."

"I'm a ballistics hunter," she said, with more pride, it seemed to me, than such a statement called for.

She could not have missed the fact that I did not understand. "I use only a ballistics rifle," she explained. "One that uses a bullet propelled by an explosive charge. It is," she said, "the only sporting way to hunt. It requires a considerable amount of skill in weapon handling and occasionally some nerve. It you miss a vital spot the thing that you are hunting has a chance at you."

"I see," I said. "A sporting proposition. Except that you have the first crack at it."

"That is not always true," she said.

A robot brought the drinks and we settled down as comfortably as we could, fortified behind our glasses.

"I have a feeling, captain," Sara said, "that you do not approve."

"I have no opinion at all," I told her. "I have no information on which opinion could be based."

"But you have killed wild creatures."

"A few," I said, "but there was no such thing involved as sporting instinct. For food, occasionally. At times to save my life."

I took a good long drink. "I took no chance," I told her. "I used a laser gun. I just kept burning them as long as it seemed necessary."

"Then you're no sportsman, captain."

"No," I said, "I am—let us say I was—a planet hunter. It seems I'm now retired."

And I wondered, sitting there, what it was all about. She hadn't invited me, I was sure, just for my company. I didn't fit in this room, nor in this house, any better than the other two who sat there with me. Whatever was going on, they were a part of it and the idea of being lumped with them in any enterprise left me absolutely cold.

She must have read my mind. "I imagine you are wondering, captain, what is going on."

"Ma'am," I said, "the thought had crossed my mind."

"Have you ever heard of Lawrence Arlen Knight?"

"The Wanderer," I said. "Yes, I've heard of him. Stories told about him. That was long ago. Well before my time."

"Those stories?"

"The usual sort of stories. Space yarns. There were and are a lot of others like him. He just happened to snare the imagination of the story tellers. That name of his, perhaps. It has a ring to it. Like Johnny Appleseed or Sir Launcelot."

"But you heard . . ."

"That he was hunting something? Sure. They all are hunting something."

"But he disappeared."

"Stay out there long enough," I told her, "and keep on poking into strange areas and you're bound to disappear. Sooner or later you'll run into something that will finish you."

"But you . . ."

"I quit soon enough," I said. "But I was fairly safe, at that. All I was hunting were new planets. No Seven Cities of Cibola, no mystic El Dorado, no trance-bound Crusade of the Soul."

"You mock at us," said Friar Tuck. "I do not like a mocker."

"I did not mean to mock," I said to Sara Foster. "Space is full of tales. The one you mention is only one of many. They provide good entertainment when there's nothing else to do. And I might add that I dislike correction at the hands of a phony religico with dirty fingernails."

I put my glass down upon the table that stood beside the chair and got up on my feet.

"Thanks for the drink," I said. "Perhaps some other time . . ."

"Just a moment, please," she said. "If you will please sit down. I apologize for Tuck. But it's I you're dealing with, not him. I have a proposal that you may find attractive."

"I've retired," I said.

"Perhaps you saw the, ship standing on the field. Two berths from where you landed.

"Yes, I saw the ship. And admired it. Does it belong to you?"

She nodded. "Captain, I need someone to run that ship. How would you like the job?"

"But why me," I asked. "Surely there are other men."

She shook her head. "On Earth? How many qualified spacemen do you think there are on Earth?"

"I suppose not many."

"There are none," 'she said. "Or almost none. None I'd trust that ship to."

I sat down again. "Let's get this straight," I said. "How do you know you can trust the ship to me? What do you know about me? How did you know I had arrived on Earth?"

She looked straight at me, squinting just a little, perhaps the way she'd squint down a rifle barrel at a charging beast.

"I can trust you," she said, "because there's nowhere you can go. You're fair game out in space. Your only safety would lie in sticking with the ship."

"Fair enough," I admitted. "And how about going out in space? The Patrol . . ."

"Captain, believe me, there's nothing that can overtake that ship, And if someone should set out to 'do it, we can wear them down. We have a long, hard way to go. It would not be worth their while. And, furthermore, I think it can be arranged so that no one ever knows you've gone into space."

"That's all very interesting," I said. "Could you bring yourself to tell me where we might be going?"

She said, "We don't know where we're going."

And that was damn foolishness, of course. You don't set out on a flight until you know where you are going. If she didn't want to tell, why couldn't she just say so?

"Mr. Smith," said Sara, "knows where we are going."

I switched my head to look at him, that great lump huddled in his chair, the sightless, milk-white eyes in his flabby face.

"I have a voice in my head," he said. "I have contact with someone. I have a friend out there."

Oh, wonderful! I thought. It all comes down to this. He has a voice in his head.

"Let me guess," I said to Sara Foster. "This religious gentleman brought Mr. Smith to you."

She suddenly was angry. Her face turned white and her blue eyes seemed to narrow to gleaming jets of ice.

"You are right," she said, biting off the words, "but that's not all of it. You know, of course, that Knight was accompanied by a robot."

I nodded. "A robot by the name of Roscoe."

"And that Roscoe was a telepathic robot?"

"There's no such thing," I said.

"But there is. Or was. I've done my homework, captain. I have the specifications for this particular robot. And I had them long before Mr. Smith showed up. Also letters that Knight had written to certain friends of his. I have, perhaps, the only authentic documentation concerning Knight and what be was looking for. All of it acquired before these two gentlemen showed up and obtained from sources of which they could have had no knowledge."

"But they could have heard . . ."

"I didn't tell a soul," she said. "It was—what would you call it? Perhaps no more than a hobby. Maybe an obsession. Bits and pieces picked up here and there, with never any hope of fitting them together. It was such a fascinating legend . . ."

"And that is all it is," I said. "A legend. Built up through the years by accomplished, but nonmalicious, liars. One tiny fact is taken and twisted and interwoven with other tiny facts until all these interwoven tiny facts, forced into fictitious relationships with one another, become so complicated that there is not a shred of hope of knowing which is solid fact and which is inspired fiction."

"But letters? And specifications for a special kind of robot?"

"That would be something else again. If they were authentic."

"There is no question about their authenticity. I've made sure of that."

"And what do these letters say?"

"That he was looking for something."

"I've told you they all were looking for something. Every one of them. Some of them believed the things they were looking for are there. Some of them simply hypnotized themselves into believing it. That's the way it was in the old days, that's the way it is right now. These kind of people need some excuse for their eternal wandering. They need to graft some purpose to a purposeless existence. They're in love with space and all those new unknown worlds which lie out beyond the next horizon. There is no reason in the world why they should be batting around out there and they know this, so they concoct their reasons and . . ."

"Captain, you don't believe a word of it?"

"Not a word," I said.

It was all right with me if she let these two adventurers lead her on a wild-goose chase, but I was not about to be a party to it. Although, remembering that ship standing out there on the landing field, I admit that I was tempted. But it was impossible, I knew. Earth was sanctuary and needed sanctuary.

"You do not like me," Friar Tuck paid to me. "And I don't like you, either. But let me tell you, honestly, that I brought my blind companion to Miss Foster with no thought of monetary gain. I am past all need of monetary gain. All I seek is truth."

I didn't answer him. Of what use would be an answer? I'd 'known his breed before.

"I cannot see," said Smith, speaking not to us, not even to himself, but to some unknown person that no one knew about. "I have never seen. I know no shape except the shapes that my hands can tell me. I can envision objects in my imagination, but the vision must be wrong, for I do not know of colors, although I am told there is such a thing as color. Red means something to you, but it is meaningless to me. There is no way one can describe a color to a man who cannot see. The feel of texture, yes, but no way in the world to really know of texture. Water to drink, but what does water look like? Whiskey in a glass with ice, but what does whiskey look like? Ice is hard and smooth and has a feel I'm told is cold. It is water that has turned to crystals and I understand it's white, but what is crystal, what is white?

"I have nothing of this world except the space it gives me and the thoughts of other people, but how am I to know that my interpretations of these thoughts are right? Or that, I can marshal facts correctly? I have little of this world, but I have another world." He lifted his hand and with his fingers tapped his skull. "Another world," he said, "here inside my head. Not an imagined world, but another world that's given me by another being. I do not know where this other being is, although I've been made to know he is very distant from us. That is all I know for certain—the great distance that he lies and the direction of that distance."

"So that is it," I said, looking at Sara. "He's to be the compass. We set out in the direction that he tells us and we keep on going . . ."

'That is it," she said. "That was the way it was with Roscoe."

"Knight's robot?"

"Knight's robot. That's what the letters say. Knight had it himself—just a little of it. Just enough to know there was someone out there. So he had the robot fabricated."

"A made-to-order robot? A telepathic robot?" She nodded.

It was hard to swallow. It was impossible. There was something going on here beyond all belief.

"There is truth out there," said Tuck. "A truth we cannot even guess. I'm willing to bet my life to go out and see."

"And that," I said, "is exactly what you would be doing. Even if you found the truth . . ."

"If it's out there," Sara said, "someone, some time, will find it. Why can't it be us?"

I looked around the room. The heads glared down at us, fantastic and ferocious creatures from many distant planets, and some of them I'd seen before and others I had only heard about and there were a number of them that I'd never heard about, not even in the alcoholic tales told by lonely, space-worn men when they gathered with their fellows in obscure bars on planets of which perhaps not more than a thousand people knew the names.

The walls are full, I thought. There is no more room for other heads. And the glamor of hunting and of bringing home more heads may be fading, too. Perhaps not alone for Sara Foster, big game huntress, but for those other people in whose eyes. her adventures on distant planets spelled out a certain kind of status. So what more logical than to hunt another kind of game, to bring home another kind of head, to embark upon a new and more marvelous adventure?

"No one," said Sara Foster, "would ever know you'd gone into space, that you had left the Earth. You'd come here someday and a man would leave again. He'd look exactly like you, but he would not be you. He'd live here on Earth in your stead and you'd go into space."

"You have money enough to buy a deal like this?" I asked. "To buy the loyalty of such a man?"

She shrugged. "I have money enough to buy anything at all. And once we were well out in space what difference would it make if he were unmasked?"

"None at all," I said, "except I'd like to come back with the ship—if the ship comes back."

"That could be arranged," she said. "That could be taken care of."

"The man who would be me here on Earth," I asked, "might meet with a fatal accident?"

"Not that," she said. "We could never get away with that. There are too many ways to identify a man."

I got the impression she was just a little sorry so simple a solution was not possible.

I shied away from it, from the entire deal. I didn't like the people and I didn't like the project. But there was the itch to get my hands upon that ship and be out in space again. A man could die on Earth, I thought; he could suffocate. I'd seen but little of the Earth and the little I had seen I'd liked. But it was the kind of thing a man might like for a little time and then slowly grow to hate. Space was in my blood. I got restless when I was out of it too long. There was something out there that got beneath one's skin, became a part of one. The star-strewn loneliness, the silence, the sense of being anchored nowhere, of being free to go wherever one might wish and to leave whenever one might wish—this was all a part of it, but not all of it. There was something else that no man had ever found a way to put a name to. Perhaps a sense of truth, corny as it sounded.

"Think of price," said Sara Foster, "then double it. There'll be no quibbling."

"But why?" I asked. "Does money have no meaning for you?"

"Of course it has," she said, "but having it also has taught me that you must pay for what you get. And we need you, Captain Ross. You've never traveled the safe spaceways, all marked out and posted. You've been out there ahead of all the others, hunting for your planets. We can use a man like you."

A robot stepped through the doorway. "Dinner is ready to be served, Miss Foster."

She looked at me, challenging me.

"I'll think on it," I promised.

THREE

And I should have thought on it much longer, I told myself as I stood on that moon-washed desert; I never should have gone.

Smith still was crawling around on his hands and knees and whimpering. His blind-white eyes, catching the moonlight, glinted like the eyes of a hunting cat. Tuck was getting his legs unwound from the ridiculous robe he wore, stumbling toward the moaning Smith. What was it, I wondered, that made the two of them such pals? Not homosexuality, for that would have been apparent in the close confines of the space trip out from Earth; there must be within them some sort o spiritual need that reached out and touched the other. Certainly Smith would be glad of someone to look after him and Tuck might well regard the blind man and his voice in the head as a good sort of investment, but their friendship must be something more than that. Two fumbling incompetents, perhaps, who had found in each other's weaknesses a common bond of compassion and of understanding.

The desert was almost as bright as day and, looking at the sky, I saw it was not the moon alone that accounted for the brightness. The entire vault of sky was ablaze with stars, more stars and bigger stars and brighter than I had ever seen before. The stars had not been apparent in the quick glance we had gotten of this place before the hobbies bucked us into it, but now they were—stars that seemed so close it seemed a man could reach up his hand and pick them, like the apples off a tree.

Sara was on her feet by now, still grasping her rifle, carrying it at port arms across her body.

"I managed to keep the muzzle up," she told me.

"Well, hurrah for you," I said.

"That's the first rule, always," she told me. "Keep the muzzle up so it doesn't clog. If I hadn't, the barrel would be full of sand."

George still was wailing and now his wailing took the form of words "What happened, Tuck?" he screamed "Where are we? What happened to my friend? He has gone away. I don't hear him anymore."

"For the love of Christ," I said to Tuck, disgusted, "get him on his feet and dust him off and wipe his nose and tell him what has happened."

"I can't explain," growled Tuck, "until someone tells me what is going on."

"I can tell you that," I said. "We got took. We've been had, my friend."

"They'll come back," howled George. "They'll come back or us. They won't leave us here."

"No, of course they won't," said Tuck, hauling him to his feet. "They'll come back when the sun is up."

"The sun ain't up now, Tuck?"

"No," said Tuck. "The moon. And a—lot of stars."

And I was stuck with this, I thought. Heaved into a place where I had no idea where I was and loaded down with a couple of nincompoops and a white Diana who could only think about how she had kept he muzzle up.

I took a look around. We had been dumped on the lower slope of a dune and on either side of us the dunes heaved up to meet the night-time sky. The sky itself was empty of everything but the moon and stars. There was not a cloud in sight. And the land was empty of anything but sand. There were no trees or bushes, not a blade of vegetation. There was a slight chill in the air, but that, I figured, would be dissipated as soon as the sun came up. More than likely we had a long, hot day ahead and we hadn't any water.

Long furrows in the sand showed where our bodies had plowed through it, pushing up little mounds of sand ahead of us. We had been thrown from the direction of the other dune, and knowing exactly from where we had been thrown, it occurred to me, might have some importance. I walked out a ways and with the butt of my gun drew a long line in the sand and made some rough arrows pointing from it.

Sara watched me closely. "You think we can get back?" she asked.

"I wouldn't bet on it," I told her, shortly.

"There was a doorway of some sort," she said, "and the hobbies bucked us through it and when we landed here there wasn't any doorway."

"They had us pegged," I said, "from the minute we set down. They gave us the business, from the very start. We never had a prayer."

"But we are here," she said, "and we have to start to think how we can get out."

"If you can keep an eye on those two clowns," I said, "and see they cause no trouble, I'll go out for a look."

She regarded me gravely. "Have you anything in mind, captain? Anything in particular?"

I shook my head. "Just a look around. There could be a chance I might stumble on some water. We'll need water badly before the day is over."

"But if you lost your way . . ."

"I'll have my tracks to follow," I told her, "if a wind doesn't come up suddenly and wipe them out. If anything goes wrong, I'll fire a beam up into the sky and you loose off a shot or two to guide me back."

"You don't think the hobbies will come back to get us?"

"Do you think so?"

"I suppose not," she said. "But what's the point of it? What did they gain by it? Our luggage couldn't be worth that much to them."

"They got rid of us," I said.

"But they guided us in. If it hadn't been for that beam . . ."

"There was the ship," I said. "It could have been the ship that they were after. They had a lot of ships out on the field. They must have lured a lot of other people."

"And all of them on this planet? Or on other planets?"

"Could be," I said. "Our job right now is to see if there's any place better than this desert we can go.. We haven't any food and we have no water."

I settled the strap of my rifle on my shoulder and started to plod up the dune.

"Anything else I can do?' asked Sara.

"You might keep those two from tracking up that line I made. If a wind comes up and starts to blot it out, try to mark it somehow."

"You have a lot of faith in that line."

"Just that it's a good idea to know where we are."

"It mightn't mean a thing," she said. "We must have been thrown through some sort of space-time null-point and where we wound up wouldn't mean . . ."

"I agree," I said, "but it's all we have to go on."

I plodded up the dune and it was heavy going. My feet sank deep into the sand and I kept sliding back I could make no time. And it was hard work. Just short of its crest I stopped to rest a moment and looked back down the slope.

The three of them stood there, looking up at me. And for some reason I couldn't explain, I found myself loving them—all three of them, that creepy, soft fool of a Smith and that phony Tuck, and Sara, bless her, with her falling lock of hair and that ridiculous oldtime rifle. No matter what they were, they were human beings and somehow or other I'd have to get them out of here. For they were counting on me. To them I was the guy who had barnstormed space and rode out all sorts of trouble. I was the rough, tough character who technically headed up the expedition. I was the captain and when the chips were down it was the captain who was expected to come through. The poor, damn, trusting fools, I thought—I didn't have the least idea of what was going on and I had no plans and was as puzzled and beaten and hopeless as any one of them. But I couldn't let them know it. I had to keep on acting as if at any moment I'd come up with a trick that would get us all home free.

I lifted a hand and waved to them and I tried to keep it jaunty, but I failed. Then I clambered up the dune and over the top of it and the desert stretched before me. In every direction that I looked, it was all the same—waves of dunes as far as I could see, each dune like the other and no break at all—no trees that might hint water, absolutely nothing but a sweep of sand.

I went plunging down the dune and climbed another and from its crest the desert looked the same as ever. I could go on; I admitted to myself, climbing dunes forever and there might never be a difference. The whole damn planet might be desert, without a single break. The hobbies, when, they'd bucked us through the gate or door or whatever it might be, had known what they were doing, and if they wanted to get rid of us, they could not have done a more efficient job of it. For they, or the world of which they were a part, hadn't missed a lick. We had been tolled in by the beam and hustled off the ship and the ship been sealed and then, without the time to think, with no chance to protest, we had been heaved into this world. A bum's rush, I thought, all worked out beforehand.

I climbed another dune. There always was the chance, I kept on telling myself, that in one of those little valleys which lay between the dunes there might be something worth the finding. Water, perhaps, for water would be the thing that we would need the most. Or a path that might lead us to better country or to natives who might be able to give us some sort of help, although why anyone would want to live in a place like this was more than I could figure.

Actually, of course, I expected nothing. There was nothing in this sweep of desert upon which a man could build much hope. But when I neared the top of the dune—near enough so that I could see over the top of it—I spotted something on the crest of the dune beyond.

A birdcage sort of contraption was half buried in the crest, with its metallic ribs shimmering in the moon and starlight, like the ribcage of some great prehistoric beast that had been trapped atop the dune, bawling out its fright until death had finally quieted it.

I slipped the rifle off my shoulder and held it ready. The sliding sand carried me slowly down the dune, whispering as it slid. When I had slid so far that I could no longer see over the crest of the dune, I set off at an angle to the left and began to climb again, crouching to keep my head down. Twenty feet from the top I got down and crawled flat against the sand. When my eyes came over the crest and I could see the birdcage once again, I froze, digging in my toes to keep from sliding back.

Below the cage, I saw, was a scar of disturbed sand and even as I watched, new blobs of sand broke loose beneath the, cage and went trickling down the slope. It had not been long ago, I was sure, that the cage had impacted on the dune crest—the sand disturbed by its landing had not as yet reached a state of equilibrium and the scar was fresh.

Impacted seemed a strange word, and yet reason told me that it must have impacted, for it was most unlikely that anyone had placed it there. A ship of some sort, perhaps, although a strange sort of ship, not enclosed, but fashioned only of a frame. And if, as I thought, it were indeed a ship, it must have carried life and the life it carried was either dead within it or somewhere nearby.

I glanced slowly up and down the length of the dune and there, far to the right of where the birdcage lay, was a faint furrow, a sort of toboggan slide, plunging from the crest downward into the shadow that lay between the dunes. I strained to penetrate the shadows, but could make out nothing. I'd have to get closer to that toboggan slide.

I backed off down the dune and went spidering across it, angling to the right this time. I moved as cautiously as I could to keep down the sound of the sliding sand that broke free and went hissing down the dune face as I moved. There might be something over on the other side of that dune, listening for any sign of life.

When I thrust the upper part of my head over the dune crest, I still was short of the toboggan slide, but much closer to it and from the hollow between the dunes came a sliding, scraping sound. Straining my ears, it seemed to me that I caught some motion in the trough, but could not be sure. The Sound of sliding and of scraping stopped and then began again and once more there was a hint of movement. I slid my rifle forward so that in an instant I could aim it down into the trough.

I waited.

The slithering sound stopped, then started once again and something moved down there (I was sure of it this time) and something moaned. All sound came to an end.

There was no use of waiting any longer.

"Hello down there!" I called.

There was no answer.

"Hello," I called again.

It could be, I realized, that I was dealing with something so far removed from my own sector of the galaxy that the space patois familiar to that sector was not used by it and that we would have no communications bridge.

And then a quavering, hooting voice answered. At first it was just a noise, then, as I wrestled with the noise, I knew it to be a word, a single hooted question.

"Friend?" had been the word, "Friend," I answered.

"In need am I of friend," the hooting voice said. "Please to advance in safety. I do not carry weapon."

"I do," I said, a little grimly.

"Of it, there is no need," said the thing down in the shadows. "I am trapped and helpless."

"That is your ship up there?"

"Ship?"

"Your conveyance."

"Truly so, dear friend. It have come apart. It is inoperative."

"I'm coming down," I told it. "I'll have my weapon on you. One move out of you . . ."

"Come then," the hooter croaked. "No move out of me. I shall lie supine."

I came to my feet and went across the top of that dune as quickly as I could and plunging down the other slope, crouched to present as small a target as was possible. I kept the rifle trained on that shadowed area from which the voice came.

I slid into the trough and crouched there, bending low to sight up its length. Then I saw it, a hump of blackness lying very still.

"All right," I called. "Move toward me now."

The hump heaved and wallowed, then lay still again, "Move," it said, "I cannot."

"OK, then. Lie still. Do not move at all."

I ran forward and stopped. The hump lay still. It did not even twitch.

I moved closer, watching it intently. Now I could see it better. From the front of its head a nest of tentacles sprouted, now lying limply on the ground. From its rather massive head, if the tentacle-bearing portion of it actually was its head, its body tapered back, four feet or so, and ended in a bluntness. It seemed to have no feet or arms. With those tentacles, perhaps, it had no need of arms. It wore no clothing, upon its body was no sign of any sort of harness. The tentacles grasped no tool or weapon.

"What is your trouble?" I asked. "What can I do for you?"

The tentacles lifted, undulating like a basketful of snakes. The hoarse voice came out of a mouth which the tentacles surrounded.

"My legs are short," it said. "I sink. They do not carry me. With them I only churn up sand. I dig with them a deeper pit beneath me."

Two of the tentacles, with eyes attached to their tips, were aimed directly at me. They looked me up and down.

"I can hoist you out of there."

"It would be a useless gesture," the creature said. "I'd bog down again."

The tentacles which served as eye-stalks moved up and down, measuring me.

"You are large," it croaked; "Have you also strength?"

"You mean to carry you?"

"Only to a place," the creature said, "where there is firmness under me."

"I don't know of such a place," I said.

"You do not know . . . Then you are not a native of this planet."

"I am not," I said. "I had thought, perhaps, that you . . .

"Of this planet, sir?" it asked. "No self-respecting member of my race would deign to defecate upon such a planet."

I squatted down to face him.

"How about the ship?" I asked. "If I could get you back up the dune to it . . ."

"It would not help," he told me. "There is nothing there."

"But there must be. Food and water . . ."

And I was, I must admit, considerably interested in the water.

"No need of it," he said. "I travel in my second self and I need no food or water. Slight protection from the openness of space and a little heat so my living tissues come to no great harm."

For the love of God, I asked myself, what was going on? He was in his second self and while I wondered what it might be all about, I was hesitant to ask. I knew how these things went. First surprise or horror or amazement that there could exist a species so ignorant or so inefficient that it did not have the concept, the stammering attempt to explain the basics of it, followed by a dissertation on the advantages of the concept and the pity that was felt for ones who did not have it Either that or the entire thing was taboo and not to be spoken of and an insult to even hint at what it might entail.

And that business about his living tissues. As if there might be more to him than simply living tissues.

It was all right, of course. A man runs into some strange things when he wanders out in space, but when he runs into them he can usually dodge them or disregard them and here I could do neither.

I had to do something to help this creature out, although for the life of me I couldn't figure just how I could help him much. I could pick him up and lug him back to where the others waited, but once I'd got him there he'd be no better off than he was right here. But I couldn't turn about and walk away and simply leave him there. He at least deserved the courtesy of someone demonstrating that they cared what happened to him.

From the time I had seen the ship and had realized that it was newly crashed, the idea had arisen, of course, that aboard it I might find food and water and perhaps other articles that the four of us could use. But now, I admitted, the entire thing was a complete and total washout. I couldn't help this creature and he was no help to us and the whole thing wound up as just another headache and being stuck with him.

"I can't offer you much," I told him. "There are four of us, myself and three others. We have no food or water—absolutely nothing."

"How got you here?" he asked.

I tried to tell him how we had gotten there and as I groped and stumbled for a way to say it, I figured that I was just wasting my time. After all, what did it really matter how we had gotten there? But he seemed to understand.

"Ah, so," he said.

"So you can see how little we can do for you," I said. "But you would essay to carry me to this place where the others are encamped?"

"Yes, I could do that."

"You would not mind?"

"Not at all," I told him, "if you'd like it that way."

I did mind, of course. It would be no small chore to wrestle him across the sand dunes. But I couldn't quite see myself assessing the situation and saying the hell with it and then walking out on him.

"I would like it very much," the creature said. "Other life is comfort and aloneness is not good. Also in numbers may lie strength. One can never tell."

"By the way," I said, "my name is Mike. I am from a planet called the Earth, out in the Carina Cygnus arm."

"Mike," he said, trying it out, hooting the name so it sounded like anything but Mike. "Is good. Rolls easy on the vocal cords. The locale of your planet is a puzzle to me. The terms I've never heard. The position of mine means nothing to you, too. And my name? My name is complicated matter involving identity framework that is of no consequence to people but my own. Please, you pick a name for me. You can call me what you want. Short and simple, please."

It had been a little crazy, of course, to get started on this matter of our names. The funny thing about it was that I'd not intended to. It was something that had just come out of me, almost instinctively. I had been somewhat surprised when I'd heard myself telling him my name. But now that it had been done, it did make the situation a bit more comfortable. We no longer were two alien beings that had stumbled across one another's paths. It gave each of us, it seemed, a greater measure of identity.

"How about Hoot?" I asked. And I could have kicked myself the minute I had said it. For it was not the best name in the world and he would have had every reason for resenting it. But he didn't seem to. He waved his tentacles around in a snaky sort of way and repeated the name several times.

"Is good," he finally said. "Is excellent for creature such as me."

"Hello, Mike," he said.

"Hello, Hoot," I told him.

I slung the rifle on my shoulder and got my feet well planted and reached down to get both arms around him. Finally I managed to hoist him to the other shoulder. He was heavier than he looked and his body was so rounded that it was hard to get a grip on him. But I finally got him settled and well-balanced and started up the dune.

I didn't try to go straight up, but slanted at an angle. With my feet sinking to the ankles with every step I took and the sand sliding under me, and fighting for every inch of progress, it was just as bad, or worse, than I had thought it would prove to be.

But I finally reached the crest and collapsed as easily as I could, letting Hoot down gently then just lying there and panting.

"I cause much trouble, Mike," said Hoot. "I tax your strength, exceeding."

"Let me get my breath," I said. "It's just a little farther."

I rolled over on my back and stared up at the sky. The stars glittered back at me. Straight overhead was a big blue giant that looked like a flashing jewel and a little to one side was a dull coal of a star, a red supergiant, perhaps. And a million others—as if someone had sat down and figured out how to fill the sky with stars and had come up with a pattern.

"Where is this place, Hoot?" I asked. "Where in the galaxy?"

"It's a globular cluster," he said. "I thought you knew that."

And that made sense, I 'thought. For the planet we had landed on, the one that great fool of a Smith had led us to, had been well above the galactic plane, out in space beyond the main body of the galaxy—out in globular duster country.